Speaking to and About Patients: Predicting Therapists' Tone of Voice

Speaking to and About Patients: Predicting Therapists' Tone of Voice

Speaking to and About Patients: Predicting Therapists' Tone of Voice

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Journal <strong>of</strong> Consulting <strong>and</strong> Clinical Psychology1984, Vol. 52, No. 4, 679-686Copyright 1984 by theAmerican Psychological Association, inc.<strong>Speaking</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>About</strong> <strong>Patients</strong>: <strong>Predicting</strong><strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Voice</strong>Robert Rosenthal <strong>and</strong>Peter David BlanckHarvard UniversityMarsha VannicelliMcLean Hospital, Belmont, MassachusettsThe <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in which therapists spoke about their alcoholic <strong>and</strong>/or drugabusingpatients was employed <strong>to</strong> predict the <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in which these sametherapists would speak <strong>to</strong> these same patients. Clips <strong>of</strong> speech ranging from 10 s<strong>to</strong> 1 min were content filtered <strong>and</strong> rated by judges. The results <strong>of</strong> zero-ordercorrelational analysis, multiple regression, <strong>and</strong> canonical correlational analysis allshowed clearly that predictions <strong>of</strong> therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice could be made withdiscriminant as well as predictive validity. Predictions were not only very significantstatistically, but <strong>of</strong> practically meaningful magnitudes. Therapists who spoke aboutpatients in a coldly au<strong>to</strong>cratic way tended <strong>to</strong> speak <strong>to</strong> these patients in a coldlypr<strong>of</strong>essional way. Therapists who spoke about patients in a warm <strong>and</strong> caring waytended <strong>to</strong> speak <strong>to</strong> these patients in a warm <strong>and</strong> honest <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice.The fine-grained analysis <strong>of</strong> the process <strong>of</strong>psychotherapy was given considerable impetusby the type <strong>of</strong> work reported by Pittenger,Hockett, <strong>and</strong> Danehy (1960). Their work suggestedthe verbal <strong>and</strong> nonverbal richness <strong>of</strong>just the first 5 min <strong>of</strong> the therapeutic interview.Subsequent work showed how much informationcould be conveyed by just the <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong>voice in even briefer time periods—some asshort as 2 s (Davitz, 1964; DePaulo & Rosenthai,1979; Rosenthal, Hall, DiMatteo, Rogers,& Archer, 1979; Zuckerman, DePaulo, & Rosenthal,1981; for an excellent review seeScherer, 1982). Much <strong>of</strong> this research involvedthe <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice <strong>of</strong> clinicians <strong>and</strong> other caregivers(e.g., Blanck & Rosenthal, in press;Blanck, Rosenthal, Vannicelli, & Lee, 1983;Caporael, Lukaszewski, & Culbertson, 1983;DiMatteo, 1979; Duncan, Rice, & Butler,1968; Milmoe, Novey, Kagan, & Rosenthal,1968). The results <strong>of</strong> this research, at the veryleast, strongly implicate clinicians' <strong>and</strong> othercaregivers' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice as potential media<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>of</strong> interpersonal effects such as therapy outcomes.This research was supported in part by the NationalScience Foundation.Requests for reprints should be sent <strong>to</strong> Robert Rosenthal,Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology <strong>and</strong> Social Relations, HarvardUniversity, 33 Kirkl<strong>and</strong> Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts02138.One such study showed that hostility in areferring clinician's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in speakingabout alcoholic patients served as a significantpostdic<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> referral success. The more hostilethe referring physician, as judged from brief(1.5 min) content-filtered speech samples, theless successful was that physician in gettingalcoholic patients <strong>to</strong> go <strong>to</strong> an alcoholism treatmentfacility (Milmoe, Rosenthal, Blane,Chafetz, & Wolf, 1967). It should be notedthat these content-filtered speech samples were<strong>of</strong> clinicians speaking about patients, not directly<strong>to</strong> them. Our interpretation <strong>of</strong> the results<strong>of</strong> this research, however, suggested that cliniciansprobably spoke <strong>to</strong> patients in a hostile,cold way if they spoke about those same patientsin a hostile, cold way. That seemed <strong>to</strong>be a reasonable inference but one on whichthere were no available data.The purpose <strong>of</strong> the present study was <strong>to</strong>investigate the degree <strong>to</strong> which clinicians' <strong>to</strong>ne<strong>of</strong> voice in speaking about their patients couldbe used <strong>to</strong> predict clinicians' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice inspeaking <strong>to</strong> those same patients. If <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong>voice in speaking about patients showed suchpredictive validity, it would do much morethan simply support the interpretation we had<strong>of</strong>fered some 15 years earlier.Indeed, even moderate predictive correlationscould be <strong>of</strong> great value <strong>to</strong> clinical researchers,supervisors, teachers, <strong>and</strong> facultyserving on admissions committees. Because679

Judges <strong>and</strong> RatingsTwelve (6 male <strong>and</strong> 6 female) undergraduates at HarvardUniversity were each paid <strong>to</strong> rate all three tapes (beginning,middle, <strong>and</strong> ending segments) <strong>of</strong> therapists talking <strong>to</strong> patients,<strong>and</strong> another 12 undergraduates (6 male <strong>and</strong> 6 female)were each paid <strong>to</strong> rate all three tapes <strong>of</strong> therapists talkingabout patients. Judges were r<strong>and</strong>omly assigned <strong>to</strong> one <strong>of</strong>three counterbalanced conditions representing the orderin which they would rate the three tapes (i.e., ABC, BCA,CAB). Judges were <strong>to</strong>ld that they would hear therapiststalking <strong>and</strong> that they would be able <strong>to</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> onlythe speaker's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice. Consistent with our earlierexperience with this type <strong>of</strong> study, judges were given nospecial training for their task (Rosenthal, 1982). All judgesrated all the segments (98 beginning, 98 middle, <strong>and</strong> 98ending segments) on 10 dimensions—not warm-warm,not hostile-hostile, not anxious-anxious, not dominantdominant,not empathic-empathic, not competent-competent,not optimistic-optimistic, not pr<strong>of</strong>essionalpr<strong>of</strong>essional,not honest-honest, <strong>and</strong> not liking-liking. Eachsegment was played once, <strong>and</strong> all judges were given 15s<strong>to</strong> make the 10 ratings. Each rating was made on a scalerunning from 1 (not at all warm) <strong>to</strong> 9 (very warm). Becauseratings <strong>of</strong> the beginning, middle, <strong>and</strong> ending segmentswere substantially correlated (median r ?= .49 for the shortestclips), these ratings were combined prior <strong>to</strong> subsequentanalyses (see Blanck, Rosenthal, Vannicelli, & Lee, 1983,for a detailed discussion <strong>of</strong> the various types <strong>of</strong> phase-<strong>to</strong>phase<strong>and</strong> judge-<strong>to</strong>-judge reliabilities).Principal Components AnalysisThe mean <strong>of</strong> all judges' ratings <strong>of</strong> the <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice inwhich therapists spoke <strong>to</strong> <strong>and</strong> spoke about their patientswere intercorrelated separately, <strong>and</strong> a principal componentsanalysis was computed for each <strong>of</strong> these 10X10 correlationmatrices <strong>of</strong> mean judges' ratings. For the ratings <strong>of</strong> therapists'<strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in speaking <strong>to</strong> their patients, thisanalysis yielded four interpretable fac<strong>to</strong>rs after varimaxrotation: (a) pr<strong>of</strong>essional-competent (consisting <strong>of</strong> competent,optimistic, ind pr<strong>of</strong>essional), (b) warmth (consisting<strong>of</strong> warm, not hostile, not dominant, empathic, <strong>and</strong> liking),(c) anxious, <strong>and</strong> (d) honest. Each new fac<strong>to</strong>r-based variablewas denned as the mean rating <strong>of</strong> the variables includedin that fac<strong>to</strong>r with the sign <strong>of</strong> the loading taken in<strong>to</strong> account.(Because the variances <strong>of</strong> these variables were so homogeneous,st<strong>and</strong>ardizing was not employed prior <strong>to</strong> computingmeans <strong>of</strong> ratings.) For example, the pr<strong>of</strong>essionalcompetentvariable was denned as the mean rating <strong>of</strong> competence,optimism, <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism in <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice.In this way, the 10 variables <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in speaking<strong>to</strong> patients were reduced <strong>to</strong> four fac<strong>to</strong>r-based variables forsubsequent analyses. A detailed description <strong>of</strong> the fac<strong>to</strong>rstructure <strong>of</strong> therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in talking <strong>to</strong> patientsis described in Blanck, Rosenthal, <strong>and</strong> Vanicelli (1983).For the ratings <strong>of</strong> therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in speakingabout their patients, the principal components analysisyielded seven interpretable fac<strong>to</strong>rs after varimax rotation:(a) pr<strong>of</strong>essional-competent (consisting <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>and</strong>competent, (b) warmth (consisting <strong>of</strong> warm, empathic,<strong>and</strong> liking), (c) not hostile, (d) anxious, (e) dominant, (f)optimistic, <strong>and</strong> (g) honest. Each new fac<strong>to</strong>r-based variablewas denned as the mean rating <strong>of</strong> the nonverbal variablesSPEAKING TO AND ABOUT PATIENTS 681included in that fac<strong>to</strong>r with the sign <strong>of</strong> the loading takenin<strong>to</strong> account. For example, the warmth variable was dennedas the mean rating <strong>of</strong> warmth, empathy, <strong>and</strong> liking in <strong>to</strong>ne<strong>of</strong> voice. In this way, the 10 variables were reduced <strong>to</strong>seven interpretable fac<strong>to</strong>r-based variables for subsequentanalyses. The fac<strong>to</strong>r structure <strong>of</strong> the therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong>voice in talking about patients is described in detail inBlanck, Rosenthal, <strong>and</strong> Vannicelli (1983).Reliability <strong>of</strong> Judges' RatingsThe reliability <strong>of</strong> the judges' ratings <strong>of</strong> the <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voicevariables was computed by means <strong>of</strong> intraclass correlations(Rosenthal, 1982). The effective reliability <strong>of</strong> the mean <strong>of</strong>the 12 judges' ratings for the 30-s clips (three clips <strong>of</strong> 10s each) <strong>of</strong> therapists speaking <strong>to</strong> patients ranged from .22<strong>to</strong> .82, with a median r <strong>of</strong> .59. The effective reliability <strong>of</strong>the mean <strong>of</strong> the 12 judges' ratings for the 60-s clips (threeclips <strong>of</strong> 20-s each) <strong>of</strong> therapists speaking about patientsranged from .47 <strong>to</strong> .83, with a median r <strong>of</strong> .64.In evaluating these median reliabilities <strong>of</strong> .59 <strong>and</strong> .64,respectively, one should keep in mind that they are basedon ratings <strong>of</strong> content-filtered speech <strong>of</strong> only 30-s <strong>and</strong> 60-s duration, respectively. For our present purposes the obtainedreliabilities are more than adequate; however, hadwe increased our segment lengths <strong>to</strong> 10 min, we couldhave increased our median reliabilities <strong>to</strong> .97 <strong>and</strong> .95,respectively (Rosenthal, 1982).Results <strong>and</strong> DiscussionWe employed three types <strong>of</strong> analyses <strong>to</strong> addressthe question <strong>of</strong> whether talking aboutpatients was predictive <strong>of</strong> talking <strong>to</strong> patients:(a) simple correlations, (b) multiple regressions,<strong>and</strong> (c) canonical correlation. We describeeach analysis in turn.Simple CorrelationsFor our first analysis we correlated each <strong>of</strong>the 10 variables that had been rated by judgeswhile therapists talked <strong>to</strong> patients with each<strong>of</strong> the corresponding 10 variables that had beenrated by judges while therapists talked aboutpatients. The first column <strong>of</strong> correlations <strong>of</strong>Table 1 shows the results <strong>of</strong> this analysis. All<strong>of</strong> the correlations were positive, most weresignificant, <strong>and</strong> half were significant at p

682 R. ROSENTHAL, P. BLANCK, AND M. VANNICELLITable 1<strong>Predicting</strong> <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Voice</strong> WhileTalking <strong>to</strong> 98 <strong>Patients</strong> From <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Voice</strong> While Talking <strong>About</strong> Those Same 98<strong>Patients</strong>: Simple CorrelationsMdnCorrelation correlation<strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> voicewithpredic<strong>to</strong>rwithnonpredic<strong>to</strong>r Differvariablevariable variables enceWarmthHostilityAnxietyDominanceEmpathyCompetenceOptimismPr<strong>of</strong>essionalismHonestyLiking.311***.094.083.270***.225*.253**.276***.248**.048.154.127.079.066.008.052.045.137.003.175.020Mdn .236* .059.184.015.017.262.173.208.139.245-.127.134" The difference between the medians is . 177; the median<strong>of</strong> the 10 differences is .156.* p

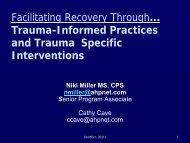

SPEAKING TO AND ABOUT PATIENTS 683mean <strong>of</strong> those two variables (pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism,competence). The supervariable <strong>of</strong> warmthwas made up <strong>of</strong> the mean <strong>of</strong> the variableswarmth, empathy, <strong>and</strong> liking. The remainingfive variables (anxiety, dominance, optimism,honesty, <strong>and</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> hostility) s<strong>to</strong>od alone.These seven variables were employed as thepredic<strong>to</strong>r battery for each <strong>of</strong> the four dependentvariables, in turn.Table 2 shows the results <strong>of</strong> the regressionanalysis. Two variables significantly predictedpr<strong>of</strong>essional competence in therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong>voice in talking <strong>to</strong> their patients: talking aboutthem in a dominant <strong>and</strong> an optimistic <strong>to</strong>ne<strong>of</strong> voice. The multiple R was not only significantstatistically (p = .002) but also substantialin magnitude (.356; see Rosenthal & Rubin,1982).The supervariable warmth (while talking <strong>to</strong>patients) was significantly predicted by thevariables <strong>of</strong> speaking about the patients in a<strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice that was not dominant, but anxious,<strong>and</strong> warm. The last <strong>of</strong> these predic<strong>to</strong>rs,warmth, was a supervariable comprised <strong>of</strong> thevariables warmth, empathy, <strong>and</strong> liking. Themultiple R <strong>of</strong> .425 was significant at p < .001.Anxiety in the therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice intalking <strong>to</strong> patients was not significantly predictedby any battery <strong>of</strong> predic<strong>to</strong>r variables.Table 2 shows that honesty in talking abouta patient was significantly related <strong>to</strong> anxietywhile talking <strong>to</strong> patients only when hostilitywas also entered in<strong>to</strong> the regression equation.The trend, though not significant, was fortherapists' anxiety in talking <strong>to</strong> patients <strong>to</strong> bepredicted from their talking about patients inan honest but hostile manner.Honesty in the therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice intalking <strong>to</strong> patients was significantly predictedby a battery <strong>of</strong> three predic<strong>to</strong>rs: talking abouttheir patients in a way that was warm, nothonest, <strong>and</strong> anxious. The multiple R <strong>of</strong> .404was significant at p < .001.The results <strong>of</strong> the four multiple regressionsshowed that three <strong>of</strong> the four dependent supervariablesdescribing therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voiceTable 2<strong>Predicting</strong> <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Voice</strong> While Talking <strong>to</strong> 98 <strong>Patients</strong> From <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Voice</strong>While Talking <strong>About</strong> Those Same 98 <strong>Patients</strong>: Multiple RegressionPredic<strong>to</strong>r variableUniquevarianceEffect size(rf<strong>Predicting</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionalcompetenceDominance .074 2.85 .006Optimism .036 1.99 .050.281.200.3566.89**<strong>Predicting</strong> warmthDominance .098 -3.35 .002Anxiety .091 3.23 .002Warmth d .042 2.19 .032-.327.316.220.4256.92*<strong>Predicting</strong> anxietyHonesty .041 2.01 .048Absence <strong>of</strong> hostility .026 -1.60 .113.202.162.2112.20*<strong>Predicting</strong> honestyWarmth" .125 3.74 .001Honesty .045 -2.26 .027Anxiety .042 2.16 .034.360-.227.217.4046.13***a For predicting pr<strong>of</strong>essional competence df= 95; for predicting warmth rf/= 94; for predicting anxiety df= 95; forpredicting honesty df = 94."Computed asc For predicting pr<strong>of</strong>essional competence dfs = 2, 95; for predicting warmth dfs = 3, 94; for predicting anxiety djs =2, 95; for predicting honesty dfs = 3, 94.d Comprised <strong>of</strong> warmth, empathy, <strong>and</strong> liking.*p = .116. ** p = .002.*** p< .001.

684 R. ROSENTHAL, P. BLANCK, AND M. VANNICELLIOPTIMISTIC.2032 /2222\ "ANXIETY /36WARMTHFigure 1. <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> voice while talking <strong>to</strong> 98 patients (four variables) as predicted from <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice whiletalking about those same 98 patients (five variables). (The four criterion variables are enclosed in boxes;the five predic<strong>to</strong>r variables are arrayed around the perimeter.)in talking <strong>to</strong> patients could be predicted significantlyfrom knowing how therapists talkedabout patients as measured on five predic<strong>to</strong>rvariables—warmth, anxiety, dominance, optimism,<strong>and</strong> honesty. The remaining two predic<strong>to</strong>rvariables <strong>of</strong> hostility <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionalcompetence in talking about patients did notcontribute significantly <strong>to</strong> the prediction <strong>of</strong>the four fac<strong>to</strong>r-based dependent variables.Figure 1 summarizes the four regressionequations graphically. The four dependentvariables are shown in boxes, <strong>and</strong> the five significantpredic<strong>to</strong>rs are shown on the perimeter<strong>of</strong> the diagram. This form <strong>of</strong> display <strong>of</strong> a se<strong>to</strong>f multiple regression equations has the advantagethat it not only shows for each dependentvariable its successful predic<strong>to</strong>rs butalso shows for each predic<strong>to</strong>r the various dependentvariables <strong>to</strong> which it makes a predictivecontribution.The single substantive conclusion that seemsclearest is that therapists who speak withwarmth <strong>and</strong> anxiety (interpreted in this contextas concern <strong>and</strong> caring) <strong>and</strong> not in a dominantmanner about their patients, treat theirpatients with warmth <strong>and</strong> honesty as judgedfrom their <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in speaking <strong>to</strong> theirpatients.Additionally, more tentative conclusionsfrom Figure 1 are that (a) therapists speaking<strong>of</strong> patients in a dominant but optimistic mannerare more likely <strong>to</strong> talk <strong>to</strong> those patientsin a pr<strong>of</strong>essionally competent manner; (b)honesty in talking about a patient may be associatedwith anxiety in talking <strong>to</strong> that patient;<strong>and</strong> (c) honesty after correction for any componen<strong>to</strong>f warmth (see Table 2) may predictdishonesty in <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice while talking <strong>to</strong>patients. Honesty corrected for warmth maybe akin <strong>to</strong> brutal frankness, a kind <strong>of</strong> "honesty"that may not be <strong>of</strong> therapeutic benefit.Canonical CorrelationIn our final analysis we examined the overallrelationship between the' seven predic<strong>to</strong>r variables<strong>and</strong> the four criterion variables we hadearlier examined in a series <strong>of</strong> four multipleregression equations. The resulting canonicalcorrelation R c was .584, p = .00022, showingthat the information in the predic<strong>to</strong>r set significantlypredicted the information in the criterionset. Of the four canonical correlationsthat could be computed, only the first wassignificant.Table 3 shows the loadings on the first canonicalvariate for the predic<strong>to</strong>r <strong>and</strong> the criterionvariables. The pattern <strong>of</strong> loadings onthe predic<strong>to</strong>r variables suggest that therapistsscoring high on this canonical variate manifesta <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in talking about patients thatis cold, uncaring (unanxious), perhaps overlypr<strong>of</strong>essional, <strong>and</strong> dominating—a pattern thatappears "coldly au<strong>to</strong>cratic." These coldly au-

SPEAKING TO AND ABOUT PATIENTS 685Table 3<strong>Predicting</strong> <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Voice</strong> WhileTalking <strong>to</strong> 98 <strong>Patients</strong> From <strong>Therapists'</strong> <strong>Tone</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Voice</strong> While Talking <strong>About</strong> Those Same 98<strong>Patients</strong>: Canonical CorrelationPredic<strong>to</strong>r variableCriterion variableVariable Loading Variable LoadingPr<strong>of</strong>essionalism-Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism-Competence .343 Competence .392Warmth -.427 Warmth -.719Absence <strong>of</strong>hostility .081 Anxiety -.082Anxiety -.490 Honesty -.516Dominance .490Optimism -.044Honesty -.131<strong>to</strong>cratic speakers about patients when speaking<strong>to</strong> patients are characterized as being cold,dishonest, <strong>and</strong> again, perhaps overly pr<strong>of</strong>essionalor "coldly pr<strong>of</strong>essional." In short, therapistswho speak <strong>of</strong> patients in a coldly au<strong>to</strong>craticway tend <strong>to</strong> speak <strong>to</strong> those patients ina coldly pr<strong>of</strong>essional way.The canonical correlation <strong>of</strong> .584 is the correlationbetween the canonical variates not theoriginal variables considered as sets. If wewant the correlation between the two sets <strong>of</strong>variables, we compute an index called^redundancy (Stewart & Love, 1968; Tucker& Chase, 1980). For the present data that correlationwas .388 considering all four canonicalvariates <strong>and</strong> .284 considering only the first canonicalvariate.The magnitudes <strong>of</strong> relationship found inthe present clinical context are quite comparable<strong>to</strong> those found in other clinical contextssuch as psychotherapy outcome research(Smith & Glass, 1977; Smith, Glass, & Miller,1980) <strong>and</strong> in other areas assessing the effects<strong>of</strong> nonverbal processes <strong>of</strong> social influence suchas the effects <strong>of</strong> interpersonal expectations(Rosenthal, 1966; Rosenthal & Jacobson,1968; Rosenthal & Rubin, 1978).ConclusionThe present study shows that therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne<strong>of</strong> voice in talking about patients can be used<strong>to</strong> make significantly accurate predictionsabout therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice in talking <strong>to</strong>patients. Our research shows, furthermore,that these predictions are characterized by discriminantvalidity as well as predictive validity.The predictions about therapists' <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voiceare not only significant statistically but alsopractically meaningful in magnitude. Correlationsbased on the median simple, the medianmultiple, <strong>and</strong> the cumulative canonicalcorrelations were .24, .38, <strong>and</strong> .39, respectively.These correlations are associated with improvementsin prediction from 38% <strong>to</strong> 62%,from 31% <strong>to</strong> 69%, <strong>and</strong> from 30.5% <strong>to</strong> 69.5%,respectively (Rosenthal & Rubin, 1982). Inshort, these correlations, which are about ashigh as are usually obtained in clinical research<strong>of</strong> this type (Cohen, 1977, page 81), might wellbe <strong>of</strong> practical utility if their magnitude holdsup on replication.We are intrigued by the possibility that suchbrief clips <strong>of</strong> content-filtered speech might beuseful not only for further research on psychotherapeuticprocess but also, in the future,for the selection <strong>and</strong> supervision <strong>of</strong> therapistsas well.ReferencesAmerican Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic <strong>and</strong>statistical manual <strong>of</strong> mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washing<strong>to</strong>n,DC: Author.Blanck, P. D., & Rosenthal, R. (in press). The mediation<strong>of</strong> interpersonal expectancy effects: The counselor's <strong>to</strong>ne<strong>of</strong> voice. Journal <strong>of</strong> Educational Psychology.Blanck, P. D., Rosenthal, R., & Vannicelli, M. (1983).The fac<strong>to</strong>r structure <strong>of</strong> the therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice. Unpublishedmanuscript, Harvard University, Cambridge,MA.Blanck, P. D., Rosenthal, R., Vanicelli, M., & Lee, T. D.(1983). Therapist's <strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> voice as predic<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> psychotherapeuticprocess: The first few seconds. Unpublishedmanuscript, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.Caporael, L. R., Lukaszewski, M. P., & Culbertson, G.H. (1983). Secondary baby talk: Judgments by institutionalizedelderly <strong>and</strong> their caregivers. Journal <strong>of</strong> Personality<strong>and</strong> Social Psychology, 44, 746-754.Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioralsciences (rev. ed.). NY: Academic Press.Davitz, J. R. (1964). The communication <strong>of</strong> emotionalmeaning. NY: McGraw-Hill.DePaulo, B. M., & Rosenthal, R. (1979). Ambivalence,discrepancy, <strong>and</strong> deception in nonverbal communication.In R. Rosenthal (Ed.), Skill in nonverbal communication:Individual differences (pp. 204-248).Cambridge, MA: Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.DiMatteo, M. R. (1979). Nonverbal skill <strong>and</strong> the physicianpatientrelationship. In R. Rosenthal (Ed.), Skill in nonverbalcommunication: Individual differences (pp. 104-134). Cambridge, MA: Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.Duncan, S., Jr., Rice, L. N., & Butler, J. M. (1968). <strong>Therapists'</strong>paralanguage in peak <strong>and</strong> poor psychotherapyhours. Journal <strong>of</strong> Abnormal Psychology, 73, 566-570.

686 R. ROSENTHAL, P. BLANCK, AND M. VANNICELLIMilmoe, S., Novey, M. S., Kagan, J., & Rosenthal, R.(1968). The mother's voice: Postdic<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> herbaby's behavior. Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the 76th Annual Convention<strong>of</strong> the American Psychological Association, pp.463-464.Milmoe, S., Rosenthal, R., Blanc, H. T., Chafetz, M. E.,& Wolf, I. (1967). The doc<strong>to</strong>r's voice: Postdic<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong>successful referral <strong>of</strong> alcoholic patients. Journal <strong>of</strong> AbnormalPsychology, 72, 78-84.Pittenger, R. E., Hockett, C. E, & Danehy, J. J. (1960).The first five minutes. Ithaca, NY: Martineau.Rogers, P. L., Scherer, K. R., & Rosenthal, R. (1971).Content-filtering human speech. Behavioral ResearchMethods <strong>and</strong> Instrumentation, 3, 16-18.Rosenthal, R. (1966). Experimenter effects in behavioralresearch. New York: Apple<strong>to</strong>n-Century-Cr<strong>of</strong>ts. (Enlargededition published by Irving<strong>to</strong>n Publishers, New York,1976.)Rosenthal, R. (1982). Conducting judgment studies. InK. R. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), H<strong>and</strong>book <strong>of</strong> methodsin nonverbal behavior research (pp. 287-361). NY:Cambridge University Press.Rosenthal, R., Hall, J. A., DiMatteo, M. R., Rogers,P. L., & Archer, D. (1979). Sensitivity <strong>to</strong> nonverbal communication:The PONS test. Baltimore: The JohnsHopkins University Press.Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in theclassroom. NY: Holt, Rinehart <strong>and</strong> Wins<strong>to</strong>n.Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1978). Interpersonal expectancyeffects: The first 345 studies. Behavioral <strong>and</strong>Brain Sciences, 3, 377-386.Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1982). A simple, generalpurpose display <strong>of</strong> magnitude <strong>of</strong> experimental effect.Journal <strong>of</strong> Educational Psychology, 74, 166-169.Scherer, K. R. (1982). Methods <strong>of</strong> research on vocal communication:Paradigms <strong>and</strong> parameters. In K. R. Scherer& P. Ekman (Eds.), H<strong>and</strong>book <strong>of</strong> methods in nonverbalbehavior research (pp. 136-198). NY: Cambridge UniversityPress.Smith, M. L., & Glass, G. V (1977). Meta-analysis <strong>of</strong>psychotherapy outcome studies. American Psychologist,32, 752-760.Smith, M. L., Glass, G. V, & Miller, T. I. (1980). Thebenefits <strong>of</strong> psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: The JohnsHopkins University Press.Stewart, D., & Love, W. (1968). A general canonical correlationindex. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 160-163.Tucker, R. K., & Chase, L. J. (1980). Canonical correlation.In P. R. Monge & J. N. Cappella (Eds.), Multivariatetechniques in human communication research (pp. 205-228). NY: Academic Press.Zuckerman, M., DePaulo, B. M., & Rosenthal, R. (1981).Verbal <strong>and</strong> nonverbal communication <strong>of</strong> deception. InL. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental socialpsychology (Vol. 14, pp. 1-59). NY: Academic Press.Received December 12, 1983Revision received February 15, 1984 •