Forest landscape restoration in East Africa - Tanzania Development ...

Forest landscape restoration in East Africa - Tanzania Development ...

Forest landscape restoration in East Africa - Tanzania Development ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

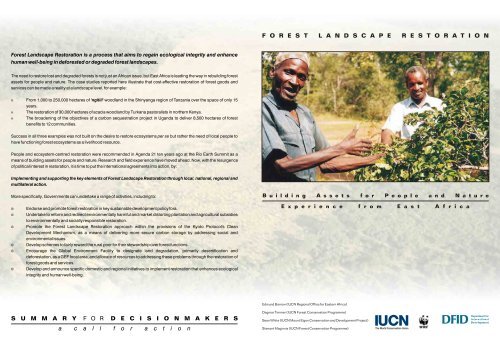

F O R E S T L A N D S C A P E R E S T O R A T I O N<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration is a process that aims to rega<strong>in</strong> ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity and enhancehuman well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> deforested or degraded forest <strong>landscape</strong>s.The need to restore lost and degraded forests is not just an <strong>Africa</strong>n issue, but <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> is lead<strong>in</strong>g the way <strong>in</strong> rebuild<strong>in</strong>g forestassets for people and nature. The case studies reported here illustrate that cost-effective <strong>restoration</strong> of forest goods andservices can be made a reality at a <strong>landscape</strong> level, for example: From 1,000 to 250,000 hectares of ‘ngitili' woodland <strong>in</strong> the Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga region of <strong>Tanzania</strong> over the space of only 15years. The <strong>restoration</strong> of 30,000 hectares of acacia woodland by Turkana pastoralists <strong>in</strong> northern Kenya. The broaden<strong>in</strong>g of the objectives of a carbon sequestration project <strong>in</strong> Uganda to deliver 8,500 hectares of forestbenefits to 12 communities.Success <strong>in</strong> all three examples was not built on the desire to restore ecosystems per se but rather the need of local people tohave function<strong>in</strong>g forest ecosystems as a livelihood resource.People and ecosystem-centred <strong>restoration</strong> were recommended <strong>in</strong> Agenda 21 ten years ago at the Rio Earth Summit as ameans of build<strong>in</strong>g assets for people and nature. Research and field experience have moved ahead. Now, with the resurgenceof political <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>restoration</strong>, it is time to put the <strong>in</strong>ternational agreements <strong>in</strong>to action, by:Implement<strong>in</strong>g and support<strong>in</strong>g the key elements of <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration through local, national, regional andmultilateral action.More specifically, Governments can undertake a range of activities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g to:B u i l d i n g A s s e t s f o r P e o p l e a n d N a t u r eEndorse and promote forest <strong>restoration</strong> <strong>in</strong> key susta<strong>in</strong>able development policy fora.Undertake to reform and redirect environmentally harmful and market distort<strong>in</strong>g plantation and agricultural subsidiesto environmentally and socially responsible <strong>restoration</strong>.Promote the <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration approach with<strong>in</strong> the provisions of the Kyoto Protocol's Clean<strong>Development</strong> Mechanism, as a means of deliver<strong>in</strong>g more secure carbon storage by address<strong>in</strong>g social andenvironmental issues.Develop schemes to fairly reward the rural poor for their stewardship over forest functions.Encourage the Global Environment Facility to designate land degradation, primarily desertification anddeforestation, as a GEF focal area, and allocate of resources to address<strong>in</strong>g these problems through the <strong>restoration</strong> offorest goods and services.Develop and announce specific domestic and regional <strong>in</strong>itiatives to implement <strong>restoration</strong> that enhances ecological<strong>in</strong>tegrity and human well-be<strong>in</strong>g.E x p e r i e n c e f r o m E a s t A f r i c aEdmund Barrow (IUCN Regional Office for <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong>)S U M M A R Y F O R D E C I S I O N M A K E R Sa c a l l f o r a c t i o nDagmar Timmer (IUCN <strong>Forest</strong> Conservation Programme)Sean White (IUCN Mount Elgon Conservation and <strong>Development</strong> Project)Stewart Mag<strong>in</strong>nis (IUCN <strong>Forest</strong> Conservation Programme)IUThe World Conservation Union

I U C N ’ s F O R E S T W O R KCopyright:© 2002 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural ResourcesISBN no: 2-8317-0664-5This booklet is pr<strong>in</strong>ted on acid and chlor<strong>in</strong>e free recycled paper.Published by:Design by:Citation:Photographs (Credits):Cover:IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UKRHME & Associates, South <strong>Africa</strong>.Barrow, Edmund; Timmer, Dagmar; White, Sean; Mag<strong>in</strong>nis, Stewart (2002). <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration:Build<strong>in</strong>g Assets for People and Nature - Experience from <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland andCambridge, UK.Mwanza Pressclub/ Obadia MugassaFarmer demonstrates the importance of tree products from his Ngitili <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, <strong>Tanzania</strong>.The designation of geographical entities <strong>in</strong> this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any op<strong>in</strong>ion whatsoever on the partof IUCN concern<strong>in</strong>g the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>g the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Theviews expressed <strong>in</strong> this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN.Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holderprovided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior writtenpermission of the copyright holder.Available from:A catalogue of IUCN publications is also available.Acknowledgements:IUCN Publications Services Unit, 219c Hunt<strong>in</strong>gdon Road, Cambridge CB3 ODL, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom,Tel: +44 1223 277894, Fax: +44 1223 277175, E-mail: <strong>in</strong>fo@books.iucn.org.Mette Bovenschulte, Sonja Canger, Florence Chege, Paul<strong>in</strong>e Ekaran, Rolf Hogan, John Hudson, WilliamJackson, Bariki Kaale, W<strong>in</strong>dolen Mlenge, James Okonya, Margarita Restrepo, Simon Rietbergen, Carole Sa<strong>in</strong>t-Laurent, Alastair Sarre, Jeffrey Sayer, Gill Shepherd.This publication has been made possible <strong>in</strong> part by fund<strong>in</strong>g from the UK Department for International <strong>Development</strong> (DFID). The views expressed <strong>in</strong> thispublication do not necessarily reflect DFID policies.IUCN The World Conservation Union - founded <strong>in</strong> 1948, br<strong>in</strong>gs together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations<strong>in</strong> a unique world partnership: nearly 980 members <strong>in</strong> all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to <strong>in</strong>fluence, encourage and assistsocieties throughout the world to conserve the <strong>in</strong>tegrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologicallysusta<strong>in</strong>able. The World Conservation Union builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support globalalliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels.IUCN's <strong>Forest</strong> Conservation Programmehas a proven track record with a widerange of forest conservation andsusta<strong>in</strong>able management issues - fromconserv<strong>in</strong>g prist<strong>in</strong>e ecosystems forpresent and future generations torestor<strong>in</strong>g forest <strong>landscape</strong>s that havebeen degraded or destroyed; fromdevelop<strong>in</strong>g new policy to work<strong>in</strong>g "on theground." The <strong>Forest</strong> ConservationProgramme supports field projectsaround the world, each focus<strong>in</strong>g onf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g practical ways of improv<strong>in</strong>g forestconservation and management andus<strong>in</strong>g lessons learnt from experience to<strong>in</strong>fluence policy at the national, regionaland global level.Tree-dom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>landscape</strong>s play animportant role <strong>in</strong> the provision of goodsand services to local resource users,communities and countries <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern<strong>Africa</strong>. Consequently, IUCN's RegionalOffice for <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> (IUCN EARO)started work<strong>in</strong>g more closely with theglobal forest programme <strong>in</strong> 1993, toassist the conservation and forestauthorities <strong>in</strong> the region, as well as tofocus on practical methods forconserv<strong>in</strong>g and manag<strong>in</strong>g forests.IUCN EARO works with its members andpartners to develop the knowledge baseabout these ecosystems, as well as theirimportance for biodiversity conservationand to the livelihoods of rural people.Even with<strong>in</strong> conservation areas,susta<strong>in</strong>able use of trees is be<strong>in</strong>g exploredthrough collaborative managementagreements. Lessons about balanc<strong>in</strong>gsusta<strong>in</strong>able use with biodiversityconservation are be<strong>in</strong>g used to <strong>in</strong>formand <strong>in</strong>fluence regional policy processes.IUCN champions action that tackles theproblems at their roots, throughaddress<strong>in</strong>g the underly<strong>in</strong>g causes offorest loss and degradation. Its workbenefits from its powerful coalition ofmembers (almost 1,000 nongovernmentalorganizations andgovernments), expert volunteerCommissions, and staff around theworld.Countries where IUCN works <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong>.<strong>Tanzania</strong>n farmers and extension staffdiscuss the management of their restoredNgitili <strong>in</strong> the Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga Region.Obadia Mugassa

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND CASE STUDY MATERIALSAn FLR Timel<strong>in</strong>eAlden-Wily, Liz and Mbaya, Sue (2001): Land, People and <strong>Forest</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong> at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of the 21st Century: The impact of landrelations on the role of communities <strong>in</strong> forest future. Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme.1996 WWF and IUCN launch the <strong>Forest</strong>s for Life strategy, with aspecific objective on restor<strong>in</strong>g forests.1998 IUCN <strong>in</strong>itiates a review of forest <strong>restoration</strong> activities <strong>in</strong> Vietnam,Lao PDR, Cambodia and Thailand. The subsequent dialogue withthese four governments helps broaden th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g and ideas concern<strong>in</strong>gthe rationale for, and scope of, <strong>restoration</strong> activities.1999 WWF and IUCN establish the <strong>Forest</strong>s Reborn project.2000, Segovia, Spa<strong>in</strong> A scop<strong>in</strong>g workshop on forest <strong>restoration</strong> isattended by a range of IUCN/WWF partners <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g representativesfrom: the Canadian International <strong>Development</strong> Agency (CIDA), the UKDepartment for International <strong>Development</strong> (DFID), the European Union(EU), the US Agency for International <strong>Development</strong> (USAID), The WorldBank, the World Conservation Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Centre (WCMC) and theUniversity of Queensland. The participants work on a framework andprocess, tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account regional variations and priorities, forexplor<strong>in</strong>g and promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>novative approaches to socially andecologically appropriate forest <strong>restoration</strong>. The workshop producedthe follow<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>ition:2001, Mombasa, Kenya An <strong>Africa</strong>n regional workshop organized byIUCN/WWF br<strong>in</strong>gs together participants from Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia,<strong>Tanzania</strong>, Madagascar and Cote d'Ivoire. The workshop reviews thepr<strong>in</strong>ciples of FLR <strong>in</strong> light of experience ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, Uganda,Ethiopia and Kenya. Political decision-makers jo<strong>in</strong> the workshop on thelast day to develop ideas and recommendations for action at thenational level.Kenya workshop participants learn<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>restoration</strong> efforts <strong>in</strong> Bamburi.Edmund Barrow.<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration is aprocess that aims to rega<strong>in</strong> ecological<strong>in</strong>tegrity and enhance human well-be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> deforested or degraded forest<strong>landscape</strong>s.Barrow, Edmund (1996): The Drylands of <strong>Africa</strong>: Local Participation <strong>in</strong> Tree Management. Nairobi: Initiatives Publishers (268 p).Barrow E., and Ekaran P. (2002): Restoration of Acacia tortilis Woodland by Turkana Pastoralists <strong>in</strong> Lorugum Area of Turkana District (Work<strong>in</strong>g paper).Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme (14 p).Barrow E.; Clarke J.; Grundy I.; Kamugisha Jones R.; and Tessema Y (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press): Whose Power? Whose Responsibilities? An Analysis of Stakeholders<strong>in</strong> Community Involvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> Management <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong>. Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme.Bazett, Mike (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press). Reforestation Incentives. Cambridge: IUCN.Begumana, John (Carbon Fixation on Mount Elgon: An Assessment of Carbon Dioxide Sequestration through Reforestation. Kampala: <strong>Forest</strong> Department(30p).Burgess, Neil and Clarke, G.P. (2000): Coastal <strong>Forest</strong>s of <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong>.Cambridge: IUCN.Ecott, Tim (with Mansourian, Stephanie and Dudley, Nigel - <strong>in</strong>troduction) (2002). <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration: Work<strong>in</strong>g Examples from 5 Ecoregions. UK:WWF (20p).Kigenyi F.; Gondo, P.; and Mugabe, J. (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press): Community Involvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> Management <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong>: Analysis of Policiesand Institutions. Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme.IISD (2002): Summary Report of the International Expert Meet<strong>in</strong>g on FLR at the International Institute for Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Development</strong> website. Onl<strong>in</strong>e at:http://www.iisd.ca/l<strong>in</strong>kages/sd/sdcfr/sdvol71num1.html.International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press): Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the Restoration of Degraded Primary <strong>Forest</strong>s, the Management ofSecondary <strong>Forest</strong>s and the Rehabilitation of Degraded <strong>Forest</strong> Land <strong>in</strong> Tropical Regions. Onl<strong>in</strong>e at http://www.itto.or.jp.IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme (2001): Regional Workshop on Community Involvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> Management <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong> (Work<strong>in</strong>gPaper No. 6, Kampala, Uganda). Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme.2002, Costa Rica Over 70 experts from government, academia, and<strong>in</strong>ternational and non-governmental organizations attend theInternational Expert Meet<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration. Themeet<strong>in</strong>g covers: the def<strong>in</strong>ition of FLR; stakeholder engagement at the<strong>landscape</strong> level; biophysical challenges; an enabl<strong>in</strong>g environment; anda framework for implementation. The meet<strong>in</strong>g is hosted by theGovernment of Costa Rica and the Government of the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom,<strong>in</strong> collaboration with IUCN, WWF, the International Tropical TimberOrganization (ITTO), the Canadian International <strong>Development</strong> Agency(CIDA), the Centre for International <strong>Forest</strong>ry Research (CIFOR), and theNortheast Asian <strong>Forest</strong> Forum (NEAFF). Participants request thedocumentation of more detailed FLR case studies, provid<strong>in</strong>g the basisfor this publication.IUCN/WWF (2002). <strong>Forest</strong>s and the WSSD: Discussion Paper for UNFF-2. Switzerland: IUCN (2p).IUCN/WWF (2001): <strong>Forest</strong>s for Life: Reaffirm<strong>in</strong>g the Vision. A Call for Action from WWF and IUCN. IUCN (9p).Kaale, B.; Mlenge, W.; and Barrow, E. (2002): The Potential of Ngitili for <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga Region: A <strong>Tanzania</strong>n Case Study(Work<strong>in</strong>g paper). Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme (35 p).Lamb, David and Gilmour, David (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press). Rehabilitation and Restoration of Degraded <strong>Forest</strong>s. Cambridge: IUCN.Mogaka, Hezron; Simons, Gacheke; Turpie, Jane; Emerton, Lucy; and Karanja, Francis (2001): Economic Aspects of Community Involvement <strong>in</strong>Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Forest</strong> Management <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern and Southern <strong>Africa</strong>. Nairobi: IUCN <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong> Programme.Orlando, Brett; Baldock, David; Canger, Sonja; Mackensen, Jens; Socorro Manguiat, Maria; Rietbergen, Simon; Robledo, Carmenza; Schneider, Norry; andYoung, Tomme (2002 - <strong>in</strong> press): Carbon, <strong>Forest</strong>s and People: Towards the <strong>in</strong>tegrated management of carbon sequestration, biodiversity and susta<strong>in</strong>ablelivelihoods. Gland: IUCN.The International Expert Meet<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration <strong>in</strong> Costa Rica wasattended by participants represent<strong>in</strong>g governments, <strong>in</strong>ternational and nongovernmentalorganizations, research <strong>in</strong>stitutions and universities, more than 60%from develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. IUCN/ Edmund Barrow.Sa<strong>in</strong>t-Laurent, Carole (2002). Support<strong>in</strong>g Implementation of International Agreements: The Role of <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration. Paper presented at theInternational Expert Meet<strong>in</strong>g on FLR. Toronto: IUCN (7p).SGS <strong>Forest</strong>ry Qualifor Programme (2002): Ma<strong>in</strong> Assessment Report for Project No. 6750 NL Mount Elgon National Park (December 1999, January 2002).Oxford: SGS (37p).Shepherd, G. (1995): Restor<strong>in</strong>g the Landscape: a participatory approach to manag<strong>in</strong>g the Dareda escarpment, Babati, <strong>Tanzania</strong>. London: ODI and Farm-<strong>Africa</strong>.

C O N C L U S I O NRESTORATION FROM A VILLAGE PERSPECTIVEF O R E S T L A N D S C A P E R E S T O R A T I O NThere are over 850 million hectares of degraded primary forest, regenerat<strong>in</strong>g secondary forest and degraded forest land <strong>in</strong> the tropics and a further 400million hectares of agricultural land that carries a significant tree component. In addition, CGIAR (Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research)estimates that 630 million people live on marg<strong>in</strong>al land (double the population <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g favorable land), a significant proportion of which qualifies asdegraded forest <strong>landscape</strong>s. In the humid tropics alone, up to 300 million people depend to some degree on degraded primary and secondary forest anddegraded forest land. Degraded <strong>landscape</strong>s are not only important from a social and economic perspective, many are still key repositories for biologicaldiversity.<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration shifts the emphasis from simply re-establish<strong>in</strong>g tree cover on a particular site, to ensur<strong>in</strong>g that forest <strong>landscape</strong>s have thenecessary mix of forest goods and services to meet both social and environmental needs. The potential applications of FLR <strong>in</strong>clude: promot<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>ablelivelihoods; improv<strong>in</strong>g the supply of key ecosystem services; <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the resilience of vulnerable areas to the impacts of climate change and other naturaldisasters; and extend<strong>in</strong>g biodiversity conservation beyond protected areas."Good forest <strong>restoration</strong> will be characterised by an <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity and human wellbe<strong>in</strong>g."<strong>Forest</strong>s for Life: Reaffirm<strong>in</strong>g the Vision. A Call for Action from WWF and IUCN, 2001Gill SheperdThe follow<strong>in</strong>g is an account of a forest <strong>restoration</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiative undertaken <strong>in</strong> Bermi Village, Babati District, <strong>Tanzania</strong>, as expla<strong>in</strong>ed by one-time Bermi VillageChairman Gervase Halahalay to Dr Gill Shepherd of the Overseas <strong>Development</strong> Institute <strong>in</strong> 1994 and 2001."My name is Gervase Halahalay, and I live <strong>in</strong> Bermi village at the foot of the Rift Valley escarpment <strong>in</strong> Babati district, <strong>Tanzania</strong>."The area was orig<strong>in</strong>ally very th<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>habited but dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1970s, the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n government <strong>in</strong>itiated compulsory 'villagization.' Asnew people moved <strong>in</strong>to the area, they cleared fields and built houses, and the trees on the Rift Valley escarpment began todisappear."By the 1990s, we were faced with a series of major problems. In the dry season, streams no longer ran for the whole year and therewere fewer spr<strong>in</strong>gs. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the ra<strong>in</strong>y season, the water was far more damag<strong>in</strong>g than it used to be, pour<strong>in</strong>g down the mounta<strong>in</strong>-sideand through household compounds. There were more landslides than before and the footpaths which ran up the escarpment weredeeply gullied and dangerous."By 1994, the Village Committee, decided to close our lands on the escarpment to graz<strong>in</strong>g animals and fuelwood collection for atemporary period so that natural regeneration could take place. Over the next year or two, the trees began to regenerate so rapidlythat it was obvious to everyone. Neighbour<strong>in</strong>g villages on either side of Bermi began to follow our example and to close their land onthe escarpment as well. By 2001, everyone was notic<strong>in</strong>g that streams now flow all round the year aga<strong>in</strong>, and that landslides hadbecome fewer. We also noticed an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> wild animals on the escarpment."I suppose my ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t is that villagers are far better at this k<strong>in</strong>d of plann<strong>in</strong>g and decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g at local level than anyone else.Nobody but we could ever understand the full picture, and I do not th<strong>in</strong>k that villagers would have co-operated as well with outsidersas they do among themselves. We saw first, co-operation with<strong>in</strong> one village, then several villages work<strong>in</strong>g together, and now plans todeal with the next set of management problems which have come <strong>in</strong>to focus. We have done a lot <strong>in</strong> eight years."Restoration work <strong>in</strong> the Honduras. CIDA-ACDI/ Patricio Baeza.<strong>Forest</strong> LandscapeA <strong>landscape</strong> that is, or once was, dom<strong>in</strong>ated by forests and woodlands and although nowmodified or degraded cont<strong>in</strong>ues to yield forest-related goods and services.<strong>Forest</strong> LandsProtected primary forestManaged (natural) forestRegenerat<strong>in</strong>g or managed secondary forestDegraded forest lands (wastelands)Industrial plantationAgricultural LandsAgro-forestry (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g farm fallows)Permanent cropp<strong>in</strong>gSilvi-pastoralismIntensive grass-based livestock productionSource: Interview, recorded <strong>in</strong> Shepherd, Gill (1995, 2001).

IUCN Work<strong>in</strong>g to put FLR <strong>in</strong>to PracticeTAKING ACTIONITTO Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the <strong>restoration</strong>,management and rehabilitation ofdegraded and secondary tropical forestsIUCN develop<strong>in</strong>g forest management plans with the local community <strong>in</strong> Lao PDR. IUCN Lao Office.Over the past year, IUCN's <strong>Forest</strong> Conservation Programme moved from scop<strong>in</strong>g studies <strong>in</strong> Asia and <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong>, to concrete plann<strong>in</strong>g for achiev<strong>in</strong>g<strong>restoration</strong> on the ground. IUCN's regional office <strong>in</strong> Asia completed a major study and workshop on forest <strong>restoration</strong> for Vietnam, Lao PDR, Thailand andCambodia <strong>in</strong> the lower Mekong River bas<strong>in</strong>. In <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong>, IUCN <strong>in</strong>itiated a similar process with government departments and civil society groups fromKenya, Uganda, <strong>Tanzania</strong> and Ethiopia, with an explicit focus on poverty reduction.Fitt<strong>in</strong>g the goals to the <strong>landscape</strong>One of the key challenges of FLR is to identify what type and level of <strong>restoration</strong> will be compatible with the social and physical realities on the ground. Thus, itis important to be clear on both the long-term and immediate objectives of <strong>restoration</strong> when identify<strong>in</strong>g the potential suite of technical approaches and policy<strong>in</strong>terventions. The objectives must be based on the <strong>in</strong>terests of key stakeholders, the physical <strong>landscape</strong> and the resources available. It will also depend onfactors like exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutional and land tenure arrangements, the prevail<strong>in</strong>g land-use policy framework, and biotic factors such as residual soil fertility andremnant species diversity, abundance and distribution.Objectives may also shift over time. While long-term aims may be to <strong>in</strong>crease the resilience, diversity and productivity of land-use practices and improvebiodiversity, realities on the ground may require short-term <strong>in</strong>terventions that yield immediate benefits. For example, a heavily degraded and economicallyimpoverished <strong>landscape</strong> will dictate that immediate efforts focus on recover<strong>in</strong>g primary processes and direct f<strong>in</strong>ancial benefit to local communities. Theseactivities will br<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>landscape</strong> to a start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t for further <strong>restoration</strong>.“While healthy ecosystems have built-<strong>in</strong> repair mechanisms, damage often exceeds their capacity for self-repair. An <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>restoration</strong> focus on the recoveryand ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of primary processes, rather than on replac<strong>in</strong>g structure and "near natural" species mix, can <strong>in</strong>itiate self-susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g forest <strong>restoration</strong>. Thisdoesn't imply we repair function and accept any structural development. It is simply a priority-sett<strong>in</strong>g philosophy that recognizes that achievable <strong>restoration</strong>options become more diverse once primary processes (hydrology, nutrient cycl<strong>in</strong>g, and energy flows) are recover<strong>in</strong>g." (Steven G. Whisenant - Department ofRangeland Ecology & Management, Texas A&M University)What makes FLR work?While there are many site-specific technical issues that arise <strong>in</strong> the case studies, most of the common challenges are more social and political <strong>in</strong> nature. It isclear from the experience gathered here that community support is a key element <strong>in</strong> the success of any forest <strong>landscape</strong> <strong>restoration</strong> activity. Stakeholdersneed to feel empowered to act and be sure that what they put <strong>in</strong> place will not be taken away from them. This means be<strong>in</strong>g prepared to address perennialland-use governance issues such as decentralized decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g and the transfer of access and use-rights. Traditional practices and <strong>in</strong>stitutions also playa significant role while the importance of long-term government commitment cannot be discounted. F<strong>in</strong>ally, there is no one bluepr<strong>in</strong>t for FLR. Success is<strong>in</strong>evitably built on adaptive management and driven by people who are will<strong>in</strong>g to learn.Although prepared for the humid tropics, the InternationalTropical Timber Organisation's (ITTO) guidel<strong>in</strong>es on<strong>restoration</strong> provide a particularly useful start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t forany policy maker or practitioner <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> <strong>Forest</strong>Landscape Restoration. ITTO's guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the<strong>restoration</strong> of degraded primary forest, the management ofsecondary forests and the rehabilitation of degraded forestlands <strong>in</strong> the tropical regions outl<strong>in</strong>e the social,environmental and technical criteria that should be taken<strong>in</strong>to account when design<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>restoration</strong> programme.They also reflect on the importance of a <strong>landscape</strong> levelperspective when consider<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>restoration</strong> andrehabilitation of forest lands. ITTO has developed aportfolio of 400 field projects, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 150 currently <strong>in</strong>operation, to test their policies <strong>in</strong> the field and promote bestpractice. In West and Central <strong>Africa</strong>, ITTO is fund<strong>in</strong>g six<strong>restoration</strong> projects. For example, the December Women'sMovement and <strong>in</strong>digenous communities <strong>in</strong> Ghana'sWorobong South are implement<strong>in</strong>g an ITTO project torestore the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of a degraded forest reserve and togenerate <strong>in</strong>come that will raise the liv<strong>in</strong>g standards of ruralwomen <strong>in</strong> the project area. Another project <strong>in</strong> Togo isassist<strong>in</strong>g several communities to generate <strong>in</strong>come from anold, neglected teak plantation and restore remnant naturalforests. ITTO works on policy and practice <strong>in</strong> its 56 membernations and the European Community, which represent90% of the world's tropical timber trade and 77% of theworld's tropical forests. The ITTO Guidel<strong>in</strong>es will beavailable <strong>in</strong> English, French and Spanish fromhttp://www.itto.or.jp.This Waisomo villager owns and manages a small p<strong>in</strong>e plantation beh<strong>in</strong>d his village <strong>in</strong> Fiji.WWF-Canon/ Cather<strong>in</strong>e HOLLOWAY.Perverse Incentives - Deal<strong>in</strong>g with the Economics of RestorationThere are various countries already provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>centives for natural orman-made <strong>in</strong>duced forest <strong>restoration</strong>, particularly concern<strong>in</strong>greforestation schemes, protection of natural forests <strong>in</strong> critical watershedsand related <strong>in</strong>itiatives. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, dis<strong>in</strong>centives may have an even largerimpact particularly <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g natural forest regeneration of degraded<strong>landscape</strong>s. A case <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t is the suppression of economic <strong>in</strong>centives topromote animal husbandry <strong>in</strong> the Nicoya Pen<strong>in</strong>sula of Costa Rica. Now,about 40 per cent of the area has come back <strong>in</strong> secondary forests,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the return of wild animals, whereas 20 years ago, the area wasalmost totally deforested. A classic "perverse <strong>in</strong>centive" is the age-oldlegal way of claim<strong>in</strong>g property, requir<strong>in</strong>g an "improvement" ("mejoría"),consist<strong>in</strong>g of clear<strong>in</strong>g a piece of forest to show <strong>in</strong>tent to "use the land."Cleared forest lands traditionally also command a higher sell<strong>in</strong>g pricethan forested areas. (Gerardo Budowski - Senior Professor, Department ofNatural Resources and Peace, University of Peace, Costa Rica)

MOVING FORWARD-RESEARCH ISSUES FOR FLRWhile it is encourag<strong>in</strong>g that a number of the technical challenges are already well understood and tools to facilitate stakeholder land-use negotiations havebeen developed and tested, much work still rema<strong>in</strong>s to be done <strong>in</strong> order to ref<strong>in</strong>e and strengthen approaches to FLR. An experts meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Costa Ricadur<strong>in</strong>g February 2002 identified some of the most press<strong>in</strong>g technical, ecological and social science research needs as:A greater array of case study material of both success and failure. As adaptive management is central to FLR, it is important to document thelessons that local people, foresters and politicians have learned and how they have responded.Tools and approaches for help<strong>in</strong>g stakeholder groups identify and negotiate land-use trade-offs at a <strong>landscape</strong> level. Balances will <strong>in</strong>evitablyhave to be struck between human livelihood needs and the desire to enhance ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity. Participatory approaches are well developed atthe local level, but how can they be scaled up to address <strong>landscape</strong> level issues?Collection and analysis of basel<strong>in</strong>e data needed to target <strong>restoration</strong> activities <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g identification of criteria and <strong>in</strong>dicators for <strong>landscape</strong> levelmonitor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluation.Better understand<strong>in</strong>g of how poor people <strong>in</strong>tegrate forest goods and services <strong>in</strong>to their livelihood strategies and/or what factors prevent forestresources from be<strong>in</strong>g better deployed <strong>in</strong> rural poverty alleviation.Identification of multiple function management options <strong>in</strong> degraded forests, new plantations and community-managed forest lands.Better understand<strong>in</strong>g of how different <strong>restoration</strong> technical packages that yield site-level <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> diversity (alpha diversity) can be used to<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>landscape</strong> level (or gamma) diversity.Basic research <strong>in</strong>to the impacts of climate change on modified or degraded forest <strong>landscape</strong>s.Analysis of environmental services and how they can be affected by <strong>restoration</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the functional consequences of different sorts ofdiversity. The challenge rema<strong>in</strong>s how to get the desired <strong>landscape</strong> level outcomes (e.g. species conservation, watershed protection) from manysmall site-level decisions.Basic research <strong>in</strong>to various aspects of the economics of <strong>restoration</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g analysis of <strong>in</strong>novative fund<strong>in</strong>g options for FLR and mechanismsfor valu<strong>in</strong>g forest goods and services <strong>in</strong> FLR. This also requires an assessment of the perverse <strong>in</strong>centives that currently encourage bad forestmanagement.Reach<strong>in</strong>g Beyond Local Level Stakeholders"Stakeholders at the local level are very often the easiest to f<strong>in</strong>dand work with. Those who rely on and live near forests havestrong reasons to protect and enhance it provided they havethe right to do so, or can be helped to acquire such rights. Thelogic of a connected forest <strong>landscape</strong> is much easier tounderstand at this scale, and it is at this level that the mosaic ofdiverse use, value and ownership can most easily beunderstood. However, this level needs to be balanced bynational level <strong>in</strong>stitutions and processes which can take someof the bigger decisions about the future of the nation's forests <strong>in</strong>the context of conservation, development and susta<strong>in</strong>ableuse." (Gill Shepherd - <strong>Forest</strong> Policy and EnvironmentProgramme, Oversees <strong>Development</strong> Institute)"<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>restoration</strong> activities undertaken at the site level oftenfail to take <strong>in</strong>to account the needs of other <strong>in</strong>terest groups (forexample, downstream water users) because <strong>in</strong>adequateattention is paid to the trade-offs of forest goods and servicesthat happen at the <strong>landscape</strong>-level. Institutional mandatesseldom co<strong>in</strong>cide with '<strong>landscape</strong>s' suitable for forest <strong>landscape</strong><strong>restoration</strong>. This makes br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g the right people around thetable a challenge, but one we have to take up for a successfuloutcome." (William J. Jackson - Director, Global Programme,IUCN)“Landscape <strong>restoration</strong> requires the active <strong>in</strong>volvement of localpeople. People will be motivated to get <strong>in</strong>volved if they are<strong>in</strong>spired. The local 'march aga<strong>in</strong>st burn<strong>in</strong>g' <strong>in</strong> El Salvador was ahuge success, because it provided local government officials,religious leaders, teachers and students with a fun way to get<strong>in</strong>volved. Movements are often more successful than projectsand give mean<strong>in</strong>g to people's lives." (David Kaimowitz -Director, Centre for International <strong>Forest</strong>ry Research)Br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g research and fieldwork together, Masters studentIgnatius Achoka <strong>in</strong> discussionwith a park guard <strong>in</strong> Bw<strong>in</strong>diImpenetrable <strong>Forest</strong> NationalPark <strong>in</strong> Uganda. WWF- Canon/Frederick J. Weyerhauser.WWF-Canon/ Sandra MBANEFO OBIAGO.<strong>Forest</strong> resources directly contributeto the livelihood of 90 per cent of the1.2 billion people liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> extremepoverty and <strong>in</strong>directly support thenatural environment that nourishesagriculture and the food supplies ofnearly half the population of thedevelop<strong>in</strong>g world." (The World Bank)Wholesale clearance of forest Near Xapuri Acre, Brazil. WWF-Canon/ Edward PARKER.

A guide po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g out the medic<strong>in</strong>al herb Lavageria macrocarpa used for fevers and malaria <strong>in</strong> Cameroon. WWF-Canon/ Edward PARKER.<strong>Forest</strong>s and their Services are ValuableThe estimated commercial value of products derived from or dependent on natural vegetation is US $ 500 800 billion per year, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pharmaceuticals,botanical medic<strong>in</strong>es, agricultural seeds, cosmetics and ornamental plants. This photo shows a guide po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g out the medic<strong>in</strong>al herb Lavageria macrocarpaused for fevers and malaria <strong>in</strong> Cameroon. The estimated value of ecosystem services worldwide is US $33,000 billion dollars a year!Some Key Terms<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration (FLR) - A process that aims to rega<strong>in</strong> ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity andenhance human well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> deforested or degraded forest <strong>landscape</strong>sEcological Integrity - Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the diversity and quality of ecosystems, and enhanc<strong>in</strong>g theircapacity to adapt to change and provide for the needs of future generations. <strong>Forest</strong> loss andfragmentation is a major factor <strong>in</strong> biodiversity loss and species ext<strong>in</strong>ction.Human Well-be<strong>in</strong>g - Ensur<strong>in</strong>g that all people have a role <strong>in</strong> shap<strong>in</strong>g decisions that affect their ability tomeet their needs, safeguard their livelihoods and realize their full potential.Restoration has eased the burden on woman to collect fuel wood. Obadia Mugassa.

EAST AFRICA LEADING THE WAY ON RESTORATIONAside from sequestration, FLR also offers major opportunities to address the issue of adaptation to climate change. S<strong>in</strong>ce FLR seeks to optimise futureoptions, as well as deliver immediate benefits, it can easily be employed to help <strong>in</strong>crease the resilience and the resistance of current farm<strong>in</strong>g systems,especially <strong>in</strong> regions such as <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>, to the adverse effects of climate change.The Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 1994) focuses on the rehabilitation of land, and the conservation and susta<strong>in</strong>able managementof land and water resources. In the context of the implementation of this Convention, a number of countries have <strong>in</strong>itiated afforestation and reforestationprogrammes and adopted policies related to forests. The use of greenbelts is often proposed as a <strong>landscape</strong> level response to halt the encroachment of thedesert <strong>in</strong>to urban centres and agricultural zones. However, major challenges lie ahead <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g a clearer connection between these techniques and thealleviation of the high levels of poverty endemic <strong>in</strong> dryland areas.A committee has been established to develop concrete recommendations on further steps <strong>in</strong> the implementation of this Convention. <strong>Forest</strong> LandscapeRestoration, with its focus on meet<strong>in</strong>g local needs and build<strong>in</strong>g on exist<strong>in</strong>g knowledge as illustrated <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n and Kenyan case studies offers thepotential for a broader, more comprehensive means of combat<strong>in</strong>g desertification at the <strong>landscape</strong> level, and thereby contribut<strong>in</strong>g to the successfulimplementation of this Convention.The tripartite liaison arrangement between the CBD, UNFCCC and UNCCD is <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g a process to beg<strong>in</strong> "identify<strong>in</strong>g and promot<strong>in</strong>g synergiesthrough forests and forest ecosystems."In addition to these Conventions, the UN Forum on <strong>Forest</strong>s (UNFF) has been charged by the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) with review<strong>in</strong>gprogress <strong>in</strong> the implementation of the proposals for action of the Intergovernmental Panel on <strong>Forest</strong>s (IPF). Those bodies adopted a suite of proposals foraction relevant to <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration. The IPF <strong>in</strong> particular outl<strong>in</strong>ed an approach that is consistent with FLR. One of the agreed elements of theUNFF's work is the "Rehabilitation and Restoration of Degraded Lands, and the Promotion of Natural and Planted <strong>Forest</strong>s." FLR could also contribute to theUNFF's deliberations on the economic, social and cultural aspects of forests.Deforestation for construction, fuelwood and agriculture <strong>in</strong> Madagascar. WWF-Canon/ John E. NEWBY,and discuss<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>restoration</strong> and management of woodlands <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, <strong>Tanzania</strong>. Obadia Mugassa.Regional Policy Processes Given that neighbour<strong>in</strong>g countriestend to share similar legal and <strong>in</strong>stitutional frameworks, regional forestprocesses can be a useful place to share experiences and developcommon approaches to <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration. Suchopportunities have already been taken by the Central America <strong>Forest</strong>Strategy process, which has already developed and adopted regionalguidel<strong>in</strong>es for forest <strong>restoration</strong>. <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration alsohas major potential to contribute to the objectives of the TehranProcess on Low <strong>Forest</strong> Cover Countries (LFCCs).In <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>, <strong>restoration</strong> is be<strong>in</strong>g used as a tool to promote both livelihood security and forest conservation. Thefollow<strong>in</strong>g three examples of projects from the region make it clear that the lessons from <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> are pert<strong>in</strong>ent to therest of the world.<strong>Tanzania</strong>: Local communities have improved their livelihoods by work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> partnership with the Government torevitalize a traditional practice of natural resource management.Kenya: Follow<strong>in</strong>g a severe drought, communities have re-established an extensive area of tree cover that providesfood security for humans and livestock.Uganda: A Dutch-funded tree plant<strong>in</strong>g project to compensate for emissions from European power stations hasbroadened its <strong>in</strong>itial narrow carbon sequestration objective to <strong>in</strong>clude a range of social and environmental benefitsfor the local community.Between 1980 and 1990, <strong>Africa</strong> lost an estimated 9 million hectares of forest per year. Current <strong>Africa</strong>n reforestation efforts have offset only 10% of this loss.Reforestation programmes plant<strong>in</strong>g mostly exotic species to meet fuelwood and <strong>in</strong>dustrial roundwood needs have tended to underestimate theimportance of products from <strong>in</strong>digenous forests to the livelihood security of rural people. For example, 70% of Kenyans and <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns rely on naturallyoccurr<strong>in</strong>g medic<strong>in</strong>al plants to remedy all but the most serious ailments, while 35% of rural Zimbabwean <strong>in</strong>come is derived from the use and sale of forestproducts.The follow<strong>in</strong>g case studies document some of the <strong>in</strong>novative ways <strong>in</strong> which forest <strong>restoration</strong> has been implemented <strong>in</strong> the region. They also demonstratethe importance of actively <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g those stakeholders most dependent on forests <strong>in</strong> decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g. These stakeholders need to be given secure userights and responsibilities and benefits need to be shared equitably.Perhaps the most emphatic lesson from <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> is that one does not have to wait for more research, analysis or the allocation of more resources fromcentral government. Communities and executive agencies can take action now, and build <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration from the ground up to restore forestgoods and services, mak<strong>in</strong>g an important and vital contribution to secur<strong>in</strong>g livelihoods and reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty.

RESTORATION AS A FOCUS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATIONO F I N T E R N A T I O N A L C O M M I T M E N T SThe Need for FLR <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong><strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>'s population and land pressures are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g. In the past, forest resources were often seen asseparate from local livelihood security by donor projects and government departments. This ignored the vital rolesthat forests and their products play <strong>in</strong> rural people's lives both <strong>in</strong> terms of goods and culture. This separation hashad two major consequences. Firstly, forest degradation has been rapid, as land is converted to agriculture; andsecondly, forest conservation, with the exception of its role as an energy source, is not seen as an important tool <strong>in</strong>poverty reduction and livelihood security. This is demonstrated by the relatively low importance given to forestconservation and forestry <strong>in</strong> national poverty reduction strategies.The three case studies that follow demonstrate the opposite. Trees, woodlands and forests provide criticalcomponents of rural livelihood security the ma<strong>in</strong> reason why the Sukuma people <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> have restored morethan 250,000 ha. Rural people need forest goods and services to secure their livelihoods - provid<strong>in</strong>g diversity <strong>in</strong>their diet and much-needed medic<strong>in</strong>es - and to act as a vital safety net <strong>in</strong> time of need. There is a clear messagehere for the next revision of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) <strong>in</strong> these three <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>n countriesthe goods and services provided by forests and trees need to be addressed <strong>in</strong> the PRSPs <strong>in</strong> a way that reflects theirimportance to rural people.Before and After - The Bamburi cement works <strong>in</strong> Kenya open m<strong>in</strong>ed thecoral rock, but they did not dig through to the water table - as they wouldnormally have done - <strong>in</strong> order to create a better environment for <strong>restoration</strong>.The top soil and vegetation was removed prior to the rock m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Fifteen totwenty years after the area was first planted and <strong>landscape</strong>d, the vegetationhas been restored. Pioneer tree species are gradually be<strong>in</strong>g replaced bymore climax tree types, grass and freshwater. Soil has returned and so havethe birds. IUCN EARO/ Edmund Barrow.Young Masai woman carry<strong>in</strong>g firewood- <strong>Tanzania</strong>. WWF-Canon/ John E. Newby.Although the exact term<strong>in</strong>ology is not set <strong>in</strong> stone, the elements of <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration identified <strong>in</strong> these case studies appear to be broadly <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ewith many of the key issues <strong>in</strong> the policy debate. International policy discussions now regularly encourage Governments and civil society to work beyond thesite level, and aim for multiple benefits <strong>in</strong> forest rehabilitation and <strong>restoration</strong> schemes. There has also been wide recognition of the need to deal with broaderaspects of forest ecosystem management, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g social and economic issues. Furthermore, there is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g emphasis on the need to recognize andexpand the contribution of forests to susta<strong>in</strong>able livelihoods, poverty eradication and human development.The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, 1992) conta<strong>in</strong>s a commitment by State Parties to rehabilitate and restore degraded ecosystems. Theecosystem approach is central to the work programme on forest biodiversity, reflect<strong>in</strong>g a grow<strong>in</strong>g realisation that land-use has both on-site and off-siteimpacts that affect ecosystems and people, and that land-use management decisions must consider the wider function of the ecosystem. In practice thismeans that more <strong>in</strong>novative ways are needed to take decisions across whole <strong>landscape</strong>s. This will necessitate the mean<strong>in</strong>gful <strong>in</strong>volvement of multiple <strong>in</strong>terestgroups while guarantee<strong>in</strong>g the rights of those who traditionally exercise stewardship over the forest resource. The revised work programme on forestbiodiversity, adopted <strong>in</strong> April 2002, <strong>in</strong>cludes a strong emphasis on <strong>restoration</strong>. It calls for the <strong>restoration</strong> of forest biodiversity <strong>in</strong> secondary forests and <strong>in</strong>forests established on former forestlands and other <strong>landscape</strong>s, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> plantations. Recommended activities <strong>in</strong>clude promot<strong>in</strong>g practices for<strong>restoration</strong> <strong>in</strong> accordance with the ecosystem approach, and restor<strong>in</strong>g forest biodiversity with the aim to restore ecosystem services. The CBD also placesgreat emphasis both on the role of traditional knowledge <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g effective biodiversity conservation and on the importance of equitable accessrights and benefit shar<strong>in</strong>g. The Turkana and Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga case studies <strong>in</strong> particular illustrate that effective implementation of many of the Convention'sseem<strong>in</strong>gly complex provisions is possible and that this can be achieved <strong>in</strong> a cost effective manner.The Kyoto Protocol of the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1992) offers <strong>in</strong>dustrialized country Parties implement<strong>in</strong>g theircommitment to reduce carbon emissions, the opportunity to partly offset a portion of this reduction through afforestation and reforestation projects <strong>in</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. There is a high degree of concern that many of these projects will have negative social and environmental consequences. Some earlyexperience with sequestration projects <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> has resulted <strong>in</strong> farmers who do not possess formal land tenure be<strong>in</strong>g expelled from their land and theirfarm fallow systems be<strong>in</strong>g replaced with exotic monocultures of fast grow<strong>in</strong>g trees. This raises major questions as to whether such schemes are permanentlysequester<strong>in</strong>g "additional" carbon or simply displac<strong>in</strong>g land-use change, and therefore releas<strong>in</strong>g more carbon <strong>in</strong>to the atmosphere, elsewhere.<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restoration offers opportunities to support biodiversity conservation and susta<strong>in</strong>able livelihoods under the Clean <strong>Development</strong>Mechanism (CDM), and set a high standard for <strong>in</strong>vestors and governments to develop projects with social and environmental co-benefits. This wouldencourage more carbon sequestration <strong>in</strong>itiatives like UWA/FACE that use native species to restore natural forest while provid<strong>in</strong>g tangible economic benefitsto local people.

T A N Z A N I AReviv<strong>in</strong>g Traditional Resource Management Systems to Meet Contemporary Livelihood NeedsThe semi-arid Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga <strong>landscape</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> is chang<strong>in</strong>g due to the efforts of the Sukuma people. Naturally regenerat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>digenous trees are be<strong>in</strong>g left, allowed to grow back and managed on farm and graz<strong>in</strong>g land together with associated vegetation,especially grass. "Ngitili" (or enclosure) is the name of the <strong>in</strong>digenous natural resource management system that HASHI - HifadhiArdhi Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga (the Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga Soil Conservation Programme) is us<strong>in</strong>g to restore the forest and woodland ecosystems afteryears of overgraz<strong>in</strong>g and deforestation. The programme has been so successful that <strong>in</strong> a mere 15 years the area of ngitili has risenfrom about 1,000 hectares to over 250,000 hectares. The project has been selected as one of twenty five <strong>in</strong>itiatives for the f<strong>in</strong>alround of the prestigious Equator Initiative.Map of the Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga region (<strong>Tanzania</strong>). Degraded land, devoid of trees <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga (1992).IUCN EARO/ Edmund Barrow.The Blood Lily flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> restored Afro-montane forestland, Mount Elgon. IUCN_EARO/ Edmund Barrow.A study on carbon accumulation undertaken<strong>in</strong> Mt. Elgon <strong>in</strong> 1998 <strong>in</strong>dicated that the matureforest (at 50 years old) is estimated to have apotential biomass of 430 tonnes per ha<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g root biomass, which is equivalentto 176 tons of carbon. The project plans toplant 25,000 ha. Assum<strong>in</strong>g that 25,000 ha isreforested and that all of the exist<strong>in</strong>gdegraded forest outside of the reforestationarea reaches a biomass of 430 tonnes per ha,the total carbon accumulation due to theproject is estimated at 4.6 million tonneswhich is equivalent to about 17million tonnesof carbon dioxide. (Source: Begumana J., 1998.)Mount Elgon is a solitary ext<strong>in</strong>ct volcano with one of the largest craters <strong>in</strong>the world, spann<strong>in</strong>g 8 km across. The mounta<strong>in</strong> descends to the pla<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> aseries of precipitous 'shelves' and is dissected by numerous streamscascad<strong>in</strong>g over the cliffs <strong>in</strong> spectacular waterfalls. It lies just north of theequator, about 100 km from Lake Victoria.The Sukuma people of <strong>Tanzania</strong> are agropastoralistsrely<strong>in</strong>g on livestock and crops for their livelihoods.Obadia Mugassa.Restored trees on farmland.Obadia Mugassa.Over 80% of the population own livestock to meet household needs and provide <strong>in</strong>come. In 1998, Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga region, cover<strong>in</strong>g less than six per cent of<strong>Tanzania</strong>, had an estimated 2.25 million cattle, or more than 20% of the national herd. This concentration of livestock has resulted <strong>in</strong> overgraz<strong>in</strong>g anddegradation far beyond the natural regenerative capacity of the land. Conversion of land to cash crops (cotton and rice) as well as deforestation for tsetse flyeradication has further exacerbated the problem. Over the past 60 years, state <strong>in</strong>itiatives to reduce land degradation <strong>in</strong> the region, such as compulsorydestock<strong>in</strong>g and tree plant<strong>in</strong>g, have had little success. The survival rate of planted trees <strong>in</strong> communal woodlots, for example, was below 20%. Even withawareness rais<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives, acute forest degradation cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong> the region.With the 1975 Villagization Act, farmers were relocated from their traditional homesteads to newly created settlements to facilitate the provision of socialservices. Leav<strong>in</strong>g their villages also meant leav<strong>in</strong>g beh<strong>in</strong>d their houses, farms and Ngitilis. The large villages, although an advantage for adm<strong>in</strong>istrativepurposes, were often poorly situated and made the practice of traditional adaptations to local ecological conditions more difficult. Traditional soilconservation practises were used less and less, and by 1985 only about 1,000 ha of Ngitili rema<strong>in</strong>ed.A strong memory of both <strong>in</strong>dividual and communal "Ngitili" provided the best entry po<strong>in</strong>t for forest <strong>restoration</strong> efforts. In fact, the Sukuma people had alreadysuggested that restor<strong>in</strong>g Ngitili might be an easier and better option than plant<strong>in</strong>g mostly exotic trees. This locally driven need for <strong>restoration</strong>, comb<strong>in</strong>ed withan <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly liberalized economy, and the <strong>in</strong>itiation of the HASHI project, provided the right <strong>in</strong>centives for local ownership of efforts to revitalise the<strong>in</strong>digenous Ngitili system.HASHI started field operations <strong>in</strong> 1986 as a Government soil conservation project. Indigenous knowledge and natural resource management systems wereadopted as the basis for <strong>restoration</strong>. The traditional function of Ngitili to provide fodder for the dry season was expanded to cover other products andservices required by rural people to meet their livelihood needs.Sources for Case Study <strong>in</strong>clude: SGS <strong>Forest</strong>ry Qualifor Programme (2002), UWA/FACE Project (2001)

The project raised awareness of the importance of restor<strong>in</strong>g natural resources through various media <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g video, theatre, newsletters anddemonstrations. Participatory Rural Appraisal tools were used at the village level to identify important natural resource problems, and how they could besolved. This process identified the need for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g so that villages and farmers could manage for 'improved' Ngitili. The project cont<strong>in</strong>ues to provide adviceon Ngitili management, for example which natural species should be selected for, which species are best used for enrichment or boundary plant<strong>in</strong>g, andwhich tree species and soil conservation methods are best used <strong>in</strong> any given area.In order to effectively manage the Ngitili, HASHI worked to build the capacity of both official government <strong>in</strong>stitutions - such as village government andenvironmental committees - and traditional <strong>in</strong>stitutions - such as the dagashida, a community assembly which formulates customary law and punishesthose that break it. Build<strong>in</strong>g on, rather than replac<strong>in</strong>g, such local <strong>in</strong>stitutions fosters local ownership and responsibility. Rules agreed with local communitieswere monitored by the traditional village guards, or Sungusungu.The adoption of a revitalized system of Ngitilis by communities and <strong>in</strong>dividuals is contribut<strong>in</strong>g to improved livelihood security and help<strong>in</strong>g to restore a widerrange of woodland goods - such as fodder, fruits, fuel, poles and medic<strong>in</strong>es - and services, such as improved water availability and shade. The creation oflocal ownership at the village or <strong>in</strong>dividual level has been critical to the success and spread of Ngitili <strong>restoration</strong> not just <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, but also toneighbour<strong>in</strong>g regions. Trees are be<strong>in</strong>g planted around homesteads, schools and villages, and on farm land and along farm borders. Naturally regenerat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>digenous trees are be<strong>in</strong>g left and managed on farm and graz<strong>in</strong>g land. While biodiversity was not a major objective of Ngitili <strong>restoration</strong>, the variety of<strong>in</strong>digenous trees and associated vegetation be<strong>in</strong>g restored has lead to an <strong>in</strong>crease of species diversity <strong>in</strong> the region. For example on Mt. Matias' farm <strong>in</strong>Sungamile village 26 tree species were found, 16 of which are <strong>in</strong>digenous.Understand<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g land use and natural resource management systems has been key to the success <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, <strong>in</strong> contrast to the externally driven,and often imposed, tree plant<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terventions before 1985. HASHI used this <strong>in</strong>digenous knowledge as the basis for <strong>restoration</strong>, while encourag<strong>in</strong>g villagegovernments to establish by-laws to protect their Ngitili. The ma<strong>in</strong> advantage of us<strong>in</strong>g traditional rules is that they are well understood, they are strictlyadhered to by the majority of people, and they complement village by-laws.The fact that the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n Government has made devolution, decentralization and empowerment a practical reality greatly helped the project. In <strong>Tanzania</strong>the village is now the lowest accountable body and can pass by-laws as long as they do not conflict with higher statutes. The National land tenure andforestry policies and statutes support this devolved governance. The benefits of such devolution are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, as the Ngitili exampledemonstrates. The right conditions of decentralization, <strong>in</strong>creased tenure security and the empower<strong>in</strong>g approaches of HASHI comb<strong>in</strong>ed with a solidtraditional knowledge base contributed to the success of <strong>restoration</strong> <strong>in</strong> the region.The success of Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga has prompted a shift of focus with<strong>in</strong> the forestry sector <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, from externally planned and promoted schemes of treeplant<strong>in</strong>g based on exotic species, to one of <strong>restoration</strong> of, <strong>in</strong> the case of Sh<strong>in</strong>yanga, <strong>in</strong>digenous Miombo and acacia woodlands.<strong>Tanzania</strong> has about 33.5 millionhectares of forests and woodlands.Almost two-thirds of this consists ofwoodlands on unreserved land. <strong>Forest</strong>resources on unreserved lands areunder enormous pressure. Sh<strong>in</strong>yangaregion, south of Lake Victoria <strong>in</strong> northwest<strong>Tanzania</strong>, suffered from seriousforest and woodland degradation dueto over-graz<strong>in</strong>g, uncontrolled bushfires, unsusta<strong>in</strong>able wood demand (<strong>in</strong>particular for fuel), and the clear<strong>in</strong>g offorest land for agriculture and tsetse flyeradication (1940-1965). WWF- Canon/John E. NEWBY.Children display Tamar<strong>in</strong>d seeds, harvested from therestored woodland at their school.Obadia Mugassa.Rich agricultural lands as a result of the climate mitigation efforts of Mount Elgon. IUCN-EARO/ Edmund Barrow.What is the FACE Foundation? The FACE Foundation (<strong>Forest</strong>sAbsorb<strong>in</strong>g Carbon Dioxide Emissions) was orig<strong>in</strong>ally set up bythe Dutch Electricity Generat<strong>in</strong>g Board, with the objective ofestablish<strong>in</strong>g forests as carbon s<strong>in</strong>ks to offset emissions ofgreenhouse gasses from power stations <strong>in</strong> the Netherlands. Ithas s<strong>in</strong>ce evolved <strong>in</strong>to an <strong>in</strong>dependent organization with a rangeof <strong>in</strong>dustrial and bus<strong>in</strong>ess clients. The foundation has fundedcarbon sequestration projects <strong>in</strong> theNetherlands, the Czech Republic,Ecuador, Malaysia and Uganda. Jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gforces with the Uganda WildlifeAuthority (UWA), FACE plans toestablish a total of 35,000 ha of forest <strong>in</strong>Uganda - 25,000 ha <strong>in</strong> Mount ElgonNational Park and 10,000 ha <strong>in</strong> KibaaleNational Park at an annual plant<strong>in</strong>g rateof 1,500 ha.Due to local efforts, there are now over 15,000 <strong>in</strong>dividual Ngitili cover<strong>in</strong>g approximately25,000 ha, and 284 communal Ngitilis cover<strong>in</strong>g about 46,000 Ha. This represents a totalof more than 70,000 ha of important woodland restored <strong>in</strong> 172 villages surveyed, out ofthe total of 833 villages <strong>in</strong> the region. Based on these figures, it is estimated that over250,000 ha have been restored across the whole region.How will the tree plant<strong>in</strong>gs be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the long term, especially after the FACE project ends? The agreement between UWA and FACE providesfor FACE fund<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g the establishment phase. Subsequent management and protection of the forest will be the responsibility of UWA. As the trees grow,CO2is absorbed and stored <strong>in</strong> the biomass of the trees and other vegetation above and below ground. Total biomass <strong>in</strong>creases until the forest is mature, afterwhich it <strong>in</strong>creases at a m<strong>in</strong>imal rate. To qualify for carbon credits, the forest must be permanent. Under the contract arrangements between the two partners,logg<strong>in</strong>g or clear fell<strong>in</strong>g is not allowed for at least 99 years. <strong>Forest</strong> management for that period will consist of protection and periodic measurements of carbonor biomass accumulation.

“Like a good <strong>in</strong>vestment portfolio, <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Restorationsets out both to reduce risk and ensure a good, long-term rate of return."(Jeffrey Sayer - Senior Associate, WWF <strong>Forest</strong>s for Life Programme)One of the villages which border Mount Elgan National Park, and who have a collaborative agreement for access<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> resources <strong>in</strong> the park. IUCN-EARO/ Edmund Barrow.<strong>in</strong>clude power generat<strong>in</strong>g companies and other <strong>in</strong>dustrial and bus<strong>in</strong>ess clients <strong>in</strong> Europe. The credits will assist those companies which comply withemissions reduction targets set by the Kyoto Protocol of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.Initiated <strong>in</strong> 1994, the project has reforested 8,500 ha of Mt. Elgon to date. Additional areas have regenerated naturally through protection provided by theproject. Areas that were once degraded forest or cultivated plots are now covered <strong>in</strong> dense regenerat<strong>in</strong>g forest.Expand<strong>in</strong>g the availability of goods and services supplied by planted forestsThe early phases of the project focused exclusively on the goals of the two partners, namely, carbon sequestration achieved by maximiz<strong>in</strong>g biomassproduction on the site and biodiversity conservation achieved by restor<strong>in</strong>g the forest <strong>in</strong> the National Park. Other benefits that forest <strong>restoration</strong> might br<strong>in</strong>gwere not considered relevant. When community needs for subsistence forest resources conflicted with the project goals, carbon sequestration andbiodiversity conservation took precedence. People were banned from harvest<strong>in</strong>g firewood, thatch<strong>in</strong>g grass and other subsistence resources on thegrounds that this would reduce the total carbon accumulation on the site.This approach brought the authorities <strong>in</strong>to conflict with local people, and tree seedl<strong>in</strong>gs were destroyed <strong>in</strong> a number of cases. Concerns over the long-termsecurity of the reforested areas led the authorities to review their policy of exclud<strong>in</strong>g local people. At the same time, Uganda Wildlife Authority wasexperiment<strong>in</strong>g with new community based approaches to protected area management. With the assistance of IUCN, UWA pilot tested collaborativemanagement approaches with local communities on Mt. Elgon which <strong>in</strong>volved provid<strong>in</strong>g access to resources <strong>in</strong> exchange for self-regulation and resourceprotection by the community.The approach was successful and has been expanded to areas reforested under the UWA/FACE project. People are now able to enter <strong>in</strong>to formal writtenagreements with the authorities to harvest a wide variety of resources such as firewood, wild fruit and vegetables, thatch<strong>in</strong>g grass, v<strong>in</strong>es, wild honey andbamboo. The agreements are designed to permit susta<strong>in</strong>able levels of harvest and to empower the communities to regulate their use of the forest. Thecommunities have agreed to monitor forest use and protect the forest from destruction or unsusta<strong>in</strong>able use. It is expected that this will ultimately lead to lessneed for protection by the Authority and better security for the forest.The change <strong>in</strong> policy has reduced conflict between the Authority and the local people and has improved local attitudes to conservation. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2000, 12agreements have been signed between the parishes and the National Park for commercial and non-commercial harvest<strong>in</strong>g of wild resources. In addition tothe benefits of resource harvest<strong>in</strong>g, some local people are also employed by the project. Improvement <strong>in</strong> the water catchment value of the area as a result offorest <strong>restoration</strong> is an added benefit that accrues to the wider community downstream.“HASHI demonstrates that rural peopleand communities can revitalize local<strong>in</strong>stitutional mechanisms to restoreforests and woodlands, and see theimportance of natural trees andvegetation to help secure and improvetheir livelihoods." (Edmund Barrow - Coord<strong>in</strong>ator, <strong>Forest</strong>Conservation & Social Policy, IUCN Regional Office for <strong>East</strong>ern <strong>Africa</strong>)When the former chairman of Isagalavillage was asked why it had beenpossible to turn a large stretch of land <strong>in</strong>toa communal Ngitili, he said "it wasbecause the village made the decisionthemselves. It was not imposed on them."“It makes good sense to consciously lookfor any <strong>in</strong>stitutional arrangements whichare <strong>in</strong> place for manag<strong>in</strong>g naturalresources, and to then build on them for<strong>restoration</strong> activities. This soundsem<strong>in</strong>ently sensible, but <strong>in</strong> fact is rarelydone. Quite frequently it is assumed thatno <strong>in</strong>stitutional arrangements exist. It isperceived that there is a need to createand impose a new <strong>in</strong>stitutional structureon local communities. This normallydestroys the pre-exist<strong>in</strong>g arrangements,and may not provide a susta<strong>in</strong>ablealternative. It is always much better tobuild on what is already there." (David Lamb, DonGilmour, 2002 <strong>in</strong> press)Br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g Water to Wigelekeko VillageTwo children collect water from an almost dry river bed.WWF-Canon/ Sandra MBANEFO OBIAGO.Wigelekeko village suffered from a shortage of wood products,fodder and water dur<strong>in</strong>g the dry season, until HASHI extensionworkers helped turn th<strong>in</strong>gs around. In 1986, the village set aside anarea of 160 ha of degraded land as Ngitili for the production offodder, firewood, grass for thatch<strong>in</strong>g, medic<strong>in</strong>e, poles and soilconservation. After five years, the area was covered with densevegetation. Controlled collection of firewood and other goods wasallowed. In 1992, a well situated <strong>in</strong> the Ngitili, which used to havewater only dur<strong>in</strong>g the wet season, now had water all year round.The villagers attributed the <strong>in</strong>creased water supply to theconservation of their Ngitili which provided them with a strong<strong>in</strong>centive to <strong>in</strong>tensify conservation efforts. In 1997, they addedanother 20 ha to the Ngitili for water catchment purposes. Eachhousehold <strong>in</strong> the village contributed about US$4 for theconstruction of a water dam that was completed <strong>in</strong> 1998. By the endof 1999, the dam's reservoir held water throughout the year and <strong>in</strong>2000, fish<strong>in</strong>g began. The value of the water the dam provides fordomestic use was estimated to be US$26,000 per year. A specialwater<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t was constructed for livestock, and the reservoirprovides water for about 1,900 cattle. The value of the water forlivestock is estimated to be US$92,000 per annum.Now, Wigelekelo village has established a water-users group tomanage the dam. The users group, with the approval of the villageassembly, is sell<strong>in</strong>g water to outsiders to fund village communitydevelopment programmes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the conservation of thevillage Ngitili.The villagers realize the importance of natural resourceconservation, and they are actively participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> conserv<strong>in</strong>g theirNgitili. As a result they are also able to <strong>in</strong>crease the water availableto them, a crucial asset dur<strong>in</strong>g the dry season, as well as derive<strong>in</strong>come from the sale of surplus water. This contributes to livelihoodsecurity as well as to conservation.