Getting it Right from the Start - Oxfam New Zealand

Getting it Right from the Start - Oxfam New Zealand

Getting it Right from the Start - Oxfam New Zealand

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

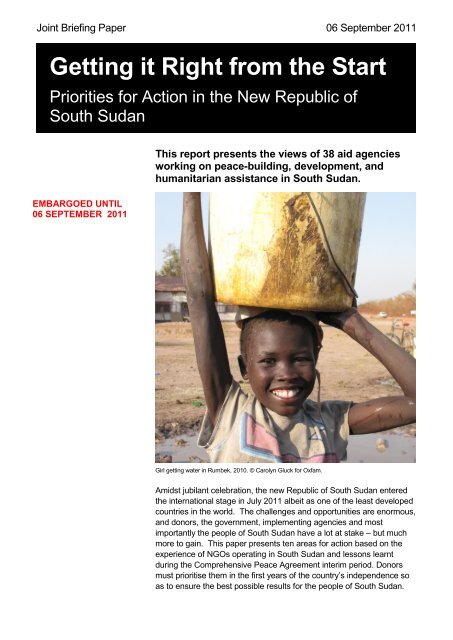

Joint Briefing Paper 06 September 2011<strong>Getting</strong> <strong>it</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Start</strong>Prior<strong>it</strong>ies for Action in <strong>the</strong> <strong>New</strong> Republic ofSouth SudanEMBARGOED UNTIL06 SEPTEMBER 2011This report presents <strong>the</strong> views of 38 aid agenciesworking on peace-building, development, andhuman<strong>it</strong>arian assistance in South Sudan.Girl getting water in Rumbek, 2010. © Carolyn Gluck for <strong>Oxfam</strong>.Amidst jubilant celebration, <strong>the</strong> new Republic of South Sudan entered<strong>the</strong> international stage in July 2011 albe<strong>it</strong> as one of <strong>the</strong> least developedcountries in <strong>the</strong> world. The challenges and opportun<strong>it</strong>ies are enormous,and donors, <strong>the</strong> government, implementing agencies and mostimportantly <strong>the</strong> people of South Sudan have a lot at stake – but muchmore to gain. This paper presents ten areas for action based on <strong>the</strong>experience of NGOs operating in South Sudan and lessons learntduring <strong>the</strong> Comprehensive Peace Agreement interim period. Donorsmust prior<strong>it</strong>ise <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> first years of <strong>the</strong> country‟s independence soas to ensure <strong>the</strong> best possible results for <strong>the</strong> people of South Sudan.

SummaryAmidst jubilant celebration in July 2011, <strong>the</strong> new Republic of SouthSudan entered <strong>the</strong> international stage albe<strong>it</strong> as one of <strong>the</strong> leastdeveloped countries in <strong>the</strong> world. One in eight children die before <strong>the</strong>irfifth birthday, <strong>the</strong> maternal mortal<strong>it</strong>y rate is one of <strong>the</strong> highest in <strong>the</strong>world and more than half <strong>the</strong> population lives below <strong>the</strong> poverty line.Against a backdrop of chronic under-development, <strong>the</strong> country isacutely vulnerable to recurring conflict and climatic shocks. More than220,000 people were displaced last year due to conflict and more than100,000 were affected by floods; and already this year, fighting in <strong>the</strong>disputed border areas, clashes between <strong>the</strong> Sudan People‟s LiberationArmy (SPLA) and mil<strong>it</strong>ia groups, disputes over land and cattle, andattacks by <strong>the</strong> Lord‟s Resistance Army, have forced nearly 300,000people <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir homes. The s<strong>it</strong>uation is exacerbated by a continuinginflux of returnees, restricted movement across <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn border,high fuel prices and regional shortages in food stocks. South Sudan is acontext that challenges normal development paradigms and f<strong>it</strong>sawkwardly in <strong>the</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian relief–recovery–post-conflictdevelopment continuum. This complex<strong>it</strong>y has not always been reflectedin <strong>the</strong> strategies of e<strong>it</strong>her donors or implementing agencies.Following sustained international attention since <strong>the</strong> signing of <strong>the</strong>Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, <strong>the</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arians<strong>it</strong>uation has improved. As explained by one county governmentauthor<strong>it</strong>y, „now <strong>the</strong>re are boreholes, some bomas have schools, … andbasic services are starting to reach to <strong>the</strong> outlying areas.‟ Manycommun<strong>it</strong>ies share <strong>the</strong> sentiment across <strong>the</strong> country.But enormous challenges remain, and human<strong>it</strong>arian and developmentactors face multiple, competing prior<strong>it</strong>ies: meeting emergencyhuman<strong>it</strong>arian needs; streng<strong>the</strong>ning commun<strong>it</strong>y resilience; addressing<strong>the</strong> underlying drivers of conflict; promoting <strong>the</strong> development ofsustainable livelihoods; ensuring that human<strong>it</strong>arian and developmentassistance promote equ<strong>it</strong>able development; supporting <strong>the</strong> governmentto protect vulnerable groups; streng<strong>the</strong>ning civil society; and ensuringuninterrupted service delivery while simultaneously streng<strong>the</strong>ningnational inst<strong>it</strong>utions and ultimately empowering <strong>the</strong> government toassume responsibil<strong>it</strong>y for meeting <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>it</strong>s c<strong>it</strong>izens.Over <strong>the</strong> coming years, donors have a window of opportun<strong>it</strong>y to support<strong>the</strong> fledgling government to tackle chronic poverty and insecur<strong>it</strong>y andmake meaningful progress towards <strong>the</strong> Millennium Development Goals.This paper highlights ten prior<strong>it</strong>y areas for action that, in <strong>the</strong> view ofNGOs operating in South Sudan and based on lessons learnt during<strong>the</strong> CPA interim period, must be prior<strong>it</strong>ised by donors in <strong>the</strong> first yearsof <strong>the</strong> country‟s independence so as to ensure <strong>the</strong> best possible resultsfor <strong>the</strong> people of South Sudan.3

Recommendations1. Balance development assistance w<strong>it</strong>h continued support foremergency human<strong>it</strong>arian needs. Recognise that <strong>the</strong>re will besubstantial human<strong>it</strong>arian needs for years to come, and ensure thathuman<strong>it</strong>arian response capac<strong>it</strong>y is adequately resourced. Continueto support international human<strong>it</strong>arian response inst<strong>it</strong>utions;streng<strong>the</strong>n efforts to build government emergency preparednessand disaster management capac<strong>it</strong>y; explore innovativemechanisms for enabling faster, more effective response; andsupport in<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> abil<strong>it</strong>y of commun<strong>it</strong>iesto prevent, m<strong>it</strong>igate and recover <strong>from</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian crises.2. Understand conflict dynamics. Comm<strong>it</strong> to rigorous andsystematic conflict analysis and to adapting development strategiesaccordingly. Ensure that funding strategies reflect <strong>the</strong> cr<strong>it</strong>ical<strong>it</strong>y of<strong>the</strong> link between secur<strong>it</strong>y and development – meaning thatadequate funding must be provided for human<strong>it</strong>arian protectionprogrammes, basic services and development, and secur<strong>it</strong>y sectorreform. In decisions regarding <strong>the</strong> geographical allocation ofinternational and national secur<strong>it</strong>y personnel, ensure that <strong>the</strong> needto protect commun<strong>it</strong>y livelihoods and food secur<strong>it</strong>y is prior<strong>it</strong>ised.3. Involve commun<strong>it</strong>ies and streng<strong>the</strong>n civil society. Providemore substantial support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives that promote commun<strong>it</strong>yparticipation in human<strong>it</strong>arian and development assistance; supportin<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at streng<strong>the</strong>ning civil society; and facil<strong>it</strong>ate accessby national NGOs and civil society organisations to internationalfunds.4. Ensure an equ<strong>it</strong>able distribution of assistance. Ensure thatinternational assistance is appropriately targeted so as to promoteequ<strong>it</strong>able social and economic development. Avoid unintentionalexclusionary effects when determining geographic focus areas,and support <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning todevelop a system for a more equ<strong>it</strong>able and transparent distributionof wealth between and w<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>the</strong> states.5. Prior<strong>it</strong>ise <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable and ensure social protection.Support <strong>the</strong> Government of South Sudan (GoSS) to develop andintroduce social protection policies, and build <strong>the</strong> capac<strong>it</strong>y of keyministries in <strong>the</strong> design and implementation of social protectionprograms. Advocate w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>the</strong> GoSS to increase <strong>it</strong>s budgetallocation to <strong>the</strong> social sectors, ensure that donor support for socialprotection does not result in a reduction of support for essentialservices, and provide greater support for programs targetingvulnerable groups.4

6. Promote pro-poor, sustainable livelihoods. Provide moresubstantial support for small-scale agricultural (andpastoral/piscicultural) production, and better targeted livelihoodssupport in areas hosting large numbers of returnees. Promoteaccess to and ownership of land for returnees, internally displacedpersons and vulnerable groups, and provide technical support for<strong>the</strong> Sudan/South Sudan border cooperation policy. Andrecognising that livelihoods will be constrained so long ascommun<strong>it</strong>ies continue to live in fear of violence, continue to supportin<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at improving local secur<strong>it</strong>y.7. Streng<strong>the</strong>n government capac<strong>it</strong>y, <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bottom up. Support<strong>the</strong> GoSS in <strong>it</strong>s comm<strong>it</strong>ment to decentralisation, provide moretargeted support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at addressing key capac<strong>it</strong>ygaps at <strong>the</strong> county level, and continue to explore innovativesolutions for increasing <strong>the</strong> number of qualified staff throughout <strong>the</strong>country.8. Allow sufficient time for trans<strong>it</strong>ion towards governmentmanagement of international aid. Build government capac<strong>it</strong>y tomanage aid funds, and build civil society capac<strong>it</strong>y to engage in <strong>the</strong>budget development and mon<strong>it</strong>oring process. Support <strong>the</strong> GoSS toestablish benchmarks for determining whe<strong>the</strong>r national systemsand inst<strong>it</strong>utions provide sufficient assurance that governmentmanagedaid brings maximum possible benef<strong>it</strong> to <strong>the</strong> people ofSouth Sudan; ensure that funding mechanisms are designed so asto facil<strong>it</strong>ate trans<strong>it</strong>ion to government management; and ensure that<strong>the</strong>re is no interruption in basic service delivery while new fundingmechanisms are being designed. And as a cr<strong>it</strong>ical part of <strong>the</strong>trans<strong>it</strong>ion process, support <strong>the</strong> GoSS to develop and implement anappropriate regulatory framework to facil<strong>it</strong>ate <strong>the</strong> work of NGOs.9. Provide timely, predictable funds. Recognise that effectiveresponse requires a range of funding mechanisms, and that thisshould include substantial bilateral funds channelled directly toimplementing agencies. Ensure that key issues experienced w<strong>it</strong>h<strong>the</strong> Common Human<strong>it</strong>arian Fund (<strong>the</strong> delayed disbursement offunds, short implementation periods and lack of synchronisationw<strong>it</strong>h <strong>the</strong> seasonal calendar) are addressed in <strong>the</strong> design of anynew such fund for South Sudan; that all new pooled funds aredesigned so as to facil<strong>it</strong>ate timely response; and that SouthSudan‟s new aid arch<strong>it</strong>ecture includes long-term (multi-year)development funding.10. Ensure integrated programming. Ensure that fundingmechanisms are broad and flexible enough to support holistic,integrated programming – meaning programming that is based onneeds assessments, multi-sectoral, and that allows for appropriatetrans<strong>it</strong>ion <strong>from</strong> relief to development. Recognise that this willrequire substantially improved donor coordination: between donorsoperating in different sectors, and between human<strong>it</strong>arian relief anddevelopment donors (including between human<strong>it</strong>arian anddevelopment offices w<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>the</strong> same donor).5

IntroductionOn 9 July, millions of South Sudanese danced and sang in <strong>the</strong> streetsas <strong>the</strong>y celebrated <strong>the</strong>ir independence. The sense of exc<strong>it</strong>ement andpromise was, and still is, palpable. As described by one national NGOstaff, independence „means that my children … can be whatever <strong>the</strong>ywant. … Before <strong>the</strong>re was nothing, now we have a future.‟ 1 And <strong>the</strong>re isgood reason for optimism. The agricultural potential of South Sudan isvast, as are <strong>the</strong> oil and mineral reserves; <strong>the</strong>re are large numbers ofhighly educated returnees; and South Sudanese throughout <strong>the</strong> countryfeel for <strong>the</strong> first time that <strong>the</strong> future is in <strong>the</strong>ir hands and are eager toplay a part in building <strong>the</strong> nation.‘This is <strong>the</strong> start, we need todo more. Every child shouldbe able to go to school. Weneed good qual<strong>it</strong>y educationin every village. We needpeace across <strong>the</strong> countryand we need educatedchildren. We need to buildthis country. We have todevelop our agriculture. Wehave mangoes and o<strong>the</strong>rfru<strong>it</strong>s, but we need <strong>the</strong> roadsto move our products. Weshould get rid of <strong>the</strong> gunstoo. War happens tooquickly because of guns.’National NGO staff, Juba,Independence Day 2011.But <strong>the</strong> Republic of South Sudan enters <strong>the</strong> international stage as oneof <strong>the</strong> least developed countries in <strong>the</strong> world. Against a backdrop ofchronic under-development, <strong>it</strong> is acutely vulnerable to recurring conflictand climatic shocks. Tensions in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn border areas remainunresolved; inter/intra communal conflict continues to flare; and <strong>the</strong>resulting displacement undermines livelihoods and food secur<strong>it</strong>y. SouthSudan is a complex context straddling <strong>the</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian - developmentparadigm. The country does not f<strong>it</strong> neatly in <strong>the</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian relief–recovery–post-conflict development continuum. This complex<strong>it</strong>y has notalways been reflected in <strong>the</strong> strategies of e<strong>it</strong>her donors or implementingagencies.Human<strong>it</strong>arian and development actors face multiple, competingprior<strong>it</strong>ies: meeting <strong>the</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian needs of crisis-affected populations;streng<strong>the</strong>ning commun<strong>it</strong>y resilience; addressing <strong>the</strong> underlying driversof conflict; promoting <strong>the</strong> development of sustainable livelihoods;ensuring that human<strong>it</strong>arian and development assistance promoteequ<strong>it</strong>able development; supporting <strong>the</strong> government to protectvulnerable groups; streng<strong>the</strong>ning civil society; and ensuringuninterrupted service delivery while simultaneously streng<strong>the</strong>ningnational inst<strong>it</strong>utions and ultimately empowering <strong>the</strong> government toassume responsibil<strong>it</strong>y for meeting <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>it</strong>s c<strong>it</strong>izens.The exc<strong>it</strong>ement following <strong>the</strong> birth of <strong>the</strong> nation is hard to overstate, but<strong>the</strong> disillusionment following a failure to deliver would be equally severe.The government and <strong>it</strong>s international partners cannot afford to fail.Over <strong>the</strong> coming years, donors have a window of opportun<strong>it</strong>y to support<strong>the</strong> fledgling government to tackle chronic poverty and insecur<strong>it</strong>y andmake meaningful progress towards <strong>the</strong> Millennium Development Goals(MDGs). This paper highlights ten prior<strong>it</strong>y areas for action based on <strong>the</strong>experience of NGOs operating in South Sudan and lessons learntduring <strong>the</strong> Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) interim period.Donors must prior<strong>it</strong>ise <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> first years of <strong>the</strong> country‟sindependence so as to ensure <strong>the</strong> best possible results for <strong>the</strong> peopleof South Sudan.6

1 Support emergency human<strong>it</strong>arianneedsSix years on <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> signing of <strong>the</strong> CPA, much of South Sudanremains a human<strong>it</strong>arian crisis. This is due in part to chronic underdevelopmentfollowing decades of war, in part to ongoing conflict, andin part to <strong>the</strong> frequent recurrence of droughts and floods.The statistics are well known. One in eight children die before <strong>the</strong>ir fifthbirthday, less than half <strong>the</strong> population has access to safe drinking waterand more than half <strong>the</strong> population live below <strong>the</strong> poverty line. Thematernal mortal<strong>it</strong>y rate is among <strong>the</strong> highest in <strong>the</strong> world, w<strong>it</strong>h one inseven women dying <strong>from</strong> pregnancy-related causes and a 15 year oldgirl more likely to die in childbirth than finish school. More than 80 percent of women are ill<strong>it</strong>erate, less than 20 per cent of <strong>the</strong> population willever vis<strong>it</strong> a health facil<strong>it</strong>y and fewer than two in ten children are fullyvaccinated against disease. 2 Last year nearly half <strong>the</strong> populationrequired food assistance or a food-related intervention at some pointduring <strong>the</strong> year. 3Droughts, floods and conflict compound <strong>the</strong> problem. More than220,000 people were forced <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir homes last year as a result ofconflict and more than 100,000 were affected by seasonal flooding –and most required some form of human<strong>it</strong>arian assistance. 4 Alreadythis year, inter/intra-communal conflict, fighting in <strong>the</strong> disputed Abyeiregion, pol<strong>it</strong>ical oppos<strong>it</strong>ion <strong>from</strong> armed groups, and attacks by <strong>the</strong>Lord‟s Resistance Army (LRA) have resulted in <strong>the</strong> displacement of anestimated 274,000 people in South Sudan. 5 Women and girls aredisproportionately affected, w<strong>it</strong>h particular needs that are easilyoverlooked when resources are stretched. The s<strong>it</strong>uation isexacerbated by restricted movement across <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn border, highfuel prices, a continuing influx of returnees and regional shortages infood stocks due to <strong>the</strong> drought across <strong>the</strong> Horn of Africa. All of thiscontributes to a substantial increase in food prices - and <strong>the</strong> likelihoodthat <strong>the</strong> 2.4m people who last year suffered moderate food insecur<strong>it</strong>ycould be pushed into severe food insecur<strong>it</strong>y w<strong>it</strong>hout substantialhuman<strong>it</strong>arian assistance. 6In <strong>the</strong> aftermath of independence, a number of donors are looking tomake a shift <strong>from</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian to development assistance. Such ashift must not come at <strong>the</strong> cost of attention to immediate human<strong>it</strong>arianneeds. The UN‟s Office for <strong>the</strong> Coordination of Human<strong>it</strong>arian Affairs(OCHA) has only recently scaled-up and still has insufficient regionalpresence to reach all of <strong>the</strong> states, <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Human<strong>it</strong>arian Affairsand Disaster Management is less than a year old, <strong>the</strong> responsecapac<strong>it</strong>y of implementing agencies is poorly spread across <strong>the</strong> states,and commun<strong>it</strong>y resilience has been weakened by decades of war.The potential for human<strong>it</strong>arian need to suddenly outstrip availableresources has been highlighted already this year. As one NGO staffsaid following <strong>the</strong> mass displacement <strong>from</strong> Abyei in May, „look howmuch trouble we‟ve had coping w<strong>it</strong>h Abyei. Imagine how we‟d go7

esponding to a worst case scenario of 200,000 – 300,000 peopledisplaced or a sudden influx of returns <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> north? If we started tosee really serious violence in Un<strong>it</strong>y State or elsewhere, we‟d beseriously stretched.‟ 7‘As South Sudan is prone torecurrent crisis … affectingcr<strong>it</strong>ical food and incomesecur<strong>it</strong>y of large segmentsof <strong>the</strong> population, support isindispensable for improvingpreparedness for, andeffective response to, foodand agricultural threats andemergencies.’Government of South Sudan, SouthSudan Economic DevelopmentPlan.Recommendations• Recognise that <strong>the</strong>re will be significant human<strong>it</strong>arian needs, andcontinued need for emergency response, for years to come. Thecapac<strong>it</strong>y of <strong>the</strong> international commun<strong>it</strong>y to adequately respond mustbe maintained, and should be resourced via funding that is fast andflexible enough to allow rapid, effective human<strong>it</strong>arian response. Thiswill be best achieved through substantial human<strong>it</strong>arian fundingchannelled bilaterally to implementing agencies, toge<strong>the</strong>r w<strong>it</strong>h anadequately resourced Common Human<strong>it</strong>arian Fund (CHF) for SouthSudan (detailed recommendations regarding <strong>the</strong> CHF are describedin section nine).• Continue to support international human<strong>it</strong>arian response inst<strong>it</strong>utions,including OCHA and <strong>the</strong> clusters (w<strong>it</strong>h a focus on streng<strong>the</strong>ningcoordination capac<strong>it</strong>y at <strong>the</strong> state level); and streng<strong>the</strong>n efforts tobuild <strong>the</strong> emergency preparedness and disaster managementcapac<strong>it</strong>y of government inst<strong>it</strong>utions at national, state and local level.This should include training for a range of government actors (suchas county health departments) in contingency planning, as well assupport for local government to develop assessment andcoordination mechanisms so as to enable appropriate, governmentleddisaster response.• Continue to explore innovative mechanisms for enabling faster, moreeffective human<strong>it</strong>arian response. In add<strong>it</strong>ion to continued support forinter-agency planning, this could include <strong>the</strong> pre-pos<strong>it</strong>ioning ofemergency response funds or <strong>the</strong> signing of contingencyagreements w<strong>it</strong>h implementing partners (as some donors havedone); or <strong>the</strong> identification of sectoral emergency response leads ineach state; or more substantial support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed atdeveloping <strong>the</strong> response capac<strong>it</strong>y of national NGOs and civil societyorganisations (CSOs).• Provide more substantial support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed atstreng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> abil<strong>it</strong>y of commun<strong>it</strong>ies to prevent, m<strong>it</strong>igate andrecover <strong>from</strong> human<strong>it</strong>arian crises. In<strong>it</strong>iatives should focus onstreng<strong>the</strong>ning existing commun<strong>it</strong>y structures – for example bysupporting commun<strong>it</strong>y leaders to develop contingency plans, orsupporting commun<strong>it</strong>y groups to play a role in raising awarenessregarding natural hazards – and particular attention should be paidto facil<strong>it</strong>ating <strong>the</strong> participation of women, children and vulnerablegroups.8

2 Understand <strong>the</strong> conflict dynamicsHuman<strong>it</strong>arian and development efforts in South Sudan must be basedon a realistic, nuanced and well-informed understanding of <strong>the</strong> evolvingcontext. This includes an understanding of <strong>the</strong> drivers and dynamics ofconflict, and an appreciation of <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong> link betweensecur<strong>it</strong>y and development.In South Sudan, drivers of conflict vary across <strong>the</strong> country and overtime, but include lack of employment opportun<strong>it</strong>ies for youth 8 ;compet<strong>it</strong>ion over natural resources; cattle-raiding; land disputes(including „land grabbing‟ by powerful individuals and large-scale landacquis<strong>it</strong>ion by private investors 9 ); ongoing Sudan/South Sudantensions; abuses by armed groups; conflict between <strong>the</strong> SPLA andrebel groups; and spill-over <strong>from</strong> neighbouring (regional) conflicts. Thecorrosive impact of <strong>the</strong>se conflict drivers is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> fact that<strong>the</strong> role trad<strong>it</strong>ionally played by tribal chiefs in non-violent conflictresolution has been eroded by displacement, urbanisation and <strong>the</strong>proliferation of small arms.A range of tools have been developed for <strong>the</strong> purpose of assistinghuman<strong>it</strong>arian and development actors to analyse and address <strong>the</strong>drivers and dynamics of conflict. But evaluations have found that inSouth Sudan, such tools are not being used to <strong>the</strong>ir full potential. Lastyear‟s multi-donor evaluation, Aiding <strong>the</strong> Peace, found that very fewdonors had „explic<strong>it</strong>ly and regularly referred to conflict analyses inprogramme planning‟, 10 and <strong>the</strong> government‟s recent „Survey forMon<strong>it</strong>oring <strong>the</strong> Implementation of <strong>the</strong> Fragile States Principles‟ foundthat a number of donors expressed doubts as to whe<strong>the</strong>r „we fullyunderstand <strong>the</strong> current context‟. 11 The use of gender-analysis inunderstanding <strong>the</strong> causes and drivers of conflict is even less likely.A lack of attention to <strong>the</strong> drivers and dynamics of conflict has a numberof possible implications: a premature shift to post-conflict recovery to<strong>the</strong> detriment of basic service delivery; supply-driven, short-termhuman<strong>it</strong>arian aid that fails to build commun<strong>it</strong>y resilience and can in factexacerbate vulnerabil<strong>it</strong>y; poorly-designed programs that address <strong>the</strong>symptoms but not <strong>the</strong> underlying causes of conflict; a focus oneconomic development w<strong>it</strong>hout due attention to related pol<strong>it</strong>ical andsecur<strong>it</strong>y prior<strong>it</strong>ies; and inadequate attention to regional secur<strong>it</strong>y threatssuch as <strong>the</strong> LRA or to developing <strong>the</strong> professionalism of <strong>the</strong> state‟s ownsecur<strong>it</strong>y forces. 12In add<strong>it</strong>ion to <strong>the</strong> under-utilisation of conflict analysis tools, <strong>the</strong>re hasalso been an under-appreciation of <strong>the</strong> link between secur<strong>it</strong>y anddevelopment. Insecur<strong>it</strong>y disrupts cultivation, lim<strong>it</strong>s movement and trade,restricts access to markets, schools and healthcare and exacerbatesvulnerabil<strong>it</strong>ies – w<strong>it</strong>h women and children almost alwaysdisproportionately affected. One example of this is in <strong>the</strong> LRA affectedareas of Western Equatoria. According to OCHA, in 2010 LRA attacksaccounted for only a minimal number of civilian casualties, but 20 percent of displacement in South Sudan during that year, w<strong>it</strong>h 45,0009

persons displaced. All this took place in a State which should havebeen <strong>the</strong> bread basket of Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sudan. 13 Instead, this State becameone of 3 states to become more food insecure in <strong>the</strong> first half of 2010. 14As noted in this year‟s World Development Report, „in highly violentsocieties, … everyday experiences, such as going to school, to work, orto market, become occasions for fear. People hes<strong>it</strong>ate to build housesor invest in small businesses because <strong>the</strong>y can be destroyed in amoment.‟ 15 Thus in <strong>the</strong> absence of adequate attention to m<strong>it</strong>igatingsecur<strong>it</strong>y threats, addressing root causes of conflict including inequ<strong>it</strong>abledevelopment, and to <strong>the</strong> professionalization of <strong>the</strong> secur<strong>it</strong>y sector, gainsin o<strong>the</strong>r sectors can easily be undermined.Recommendations• Comm<strong>it</strong> to rigorous and systematic conflict analysis that considersnot only <strong>the</strong> prevailing pol<strong>it</strong>ical and secur<strong>it</strong>y cond<strong>it</strong>ions but also <strong>the</strong>root causes of conflict, and to regularly adapting developmentstrategies on <strong>the</strong> basis of such analysis. Conflict analysis should beconducted periodically as well as in response to changes in context;and information should be geographically disaggregated so as totake account of factors that vary between states, counties and evenlocal commun<strong>it</strong>ies. Conflict analysis must also be gender-sens<strong>it</strong>ive,meaning that <strong>the</strong> particular impact of violence and displacement onwomen and men (such as exacerbated inequal<strong>it</strong>ies in genderrelations) must be taken into account and reflected in programdesign.• Ensure that funding strategies reflect <strong>the</strong> cr<strong>it</strong>ical<strong>it</strong>y of <strong>the</strong> linkbetween secur<strong>it</strong>y and development. This means that, w<strong>it</strong>h a view toprotecting commun<strong>it</strong>ies <strong>from</strong> violence, donors must ensure adequatefunds for human<strong>it</strong>arian protection programs and staff, basic servicesand development, as well as for secur<strong>it</strong>y sector reform. For much of<strong>the</strong> past six years <strong>the</strong> development of South Sudan‟s fledglingsecur<strong>it</strong>y sector has been slow w<strong>it</strong>h inadequate progress in <strong>the</strong>development of effective commun<strong>it</strong>y-oriented policing and <strong>the</strong>streng<strong>the</strong>ning of <strong>the</strong> justice system (both formal and trad<strong>it</strong>ional). 16This lack of progress must be reversed so as to ensure thatdevelopment gains in o<strong>the</strong>r areas are not undermined.• In decisions regarding <strong>the</strong> geographical allocation of SouthSudanese and international secur<strong>it</strong>y personnel, prior<strong>it</strong>ise <strong>the</strong> need toprotect commun<strong>it</strong>y livelihoods and food secur<strong>it</strong>y. This means thatsecur<strong>it</strong>y threats must be assessed according to <strong>the</strong>ir impact oncommun<strong>it</strong>ies such as restricted access to livelihoods and basicservices, and numbers displaced, and not just <strong>the</strong> number offatal<strong>it</strong>ies involved. Particular attention must be paid to <strong>the</strong> presenceof rebel commanders or armed groups that cause widespreaddisplacement and detrimentally impact upon food secur<strong>it</strong>y in areasw<strong>it</strong>h high agricultural potential – including in particular <strong>the</strong> LRA.10

3 Involve commun<strong>it</strong>ies andstreng<strong>the</strong>n civil societyEmergency Response Team – Old Fangak, Jonglei State, October 2010, © MediarThe importance of fostering <strong>the</strong> participation of local commun<strong>it</strong>ies and arange of CSOs including women‟s, youth, and fa<strong>it</strong>h-based and churchgroups in <strong>the</strong> development of South Sudan cannot be overstated.Commun<strong>it</strong>y participation enhances <strong>the</strong> relevance and sustainabil<strong>it</strong>y ofdevelopment in<strong>it</strong>iatives; while a strong civil society facil<strong>it</strong>ates goodgovernance by increasing <strong>the</strong> likelihood of local author<strong>it</strong>ies being heldaccountable to <strong>the</strong> people.Those best able to determine what is needed in order to streng<strong>the</strong>ncommun<strong>it</strong>ies are almost always <strong>the</strong> commun<strong>it</strong>ies <strong>the</strong>mselves, and <strong>the</strong>irinvolvement helps ensure commun<strong>it</strong>y ownership of developmentin<strong>it</strong>iatives. Experience in South Sudan has shown time and again thatw<strong>it</strong>hout this, results are difficult to sustain. Agencies supporting <strong>the</strong>management of commun<strong>it</strong>y water resources, for example, have foundthat w<strong>it</strong>hout commun<strong>it</strong>y involvement in choosing <strong>the</strong> s<strong>it</strong>e for waterpoints, <strong>the</strong> selection of water management comm<strong>it</strong>tee members and <strong>the</strong>establishment of rules for maintenance and <strong>the</strong> payment of user-fees,<strong>the</strong> likelihood of water resources being maintained by commun<strong>it</strong>ies issubstantially reduced. 17 This is basic development good practice, but isoften sidelined in <strong>the</strong> interests of meeting donor comm<strong>it</strong>ments in lim<strong>it</strong>edtimeframes where access to commun<strong>it</strong>ies is restricted due to long rainyseasons and poor infrastructure.It‟s not just about promoting commun<strong>it</strong>y ownership. Donors andimplementing agencies have acknowledged that throughout years ofhuman<strong>it</strong>arian and development assistance, adequate attention has notalways been paid to <strong>the</strong> development of local capac<strong>it</strong>ies 18 – and11

anecdotal evidence suggests that in some cases this may haveundermined <strong>the</strong> capac<strong>it</strong>y and desire of local commun<strong>it</strong>ies to contribute to<strong>the</strong>ir own development. A frustration commonly expressed by field staff,for example, is that <strong>the</strong>re is an expectation on <strong>the</strong> part of commun<strong>it</strong>iesthat <strong>the</strong>y will receive incentives in exchange for <strong>the</strong>ir participation. Asexplained by an NGO staff in Upper Nile, „some NGOs … dig <strong>the</strong> latrinesand <strong>the</strong>n just give <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> commun<strong>it</strong>y. After that <strong>it</strong>‟s hard to convince<strong>the</strong> commun<strong>it</strong>y to do <strong>the</strong> digging <strong>the</strong>mselves‟. 19 Countering thisexpectation requires a consistent, inter-agency approach.While some commun<strong>it</strong>ies have become accustomed to expectingservices <strong>from</strong> NGOs at no cost to <strong>the</strong>mselves, this is not <strong>the</strong> case vis-àvislocal author<strong>it</strong>ies. In South Sudan many commun<strong>it</strong>ies have noexperience w<strong>it</strong>h government service delivery, and thus areunaccustomed to expecting let alone demanding services <strong>from</strong>government. The implications of this are exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> fact thatdecades of war and <strong>the</strong> resulting disruption to commun<strong>it</strong>ies has in manyareas left behind a civil society that has lim<strong>it</strong>ed capac<strong>it</strong>y to collectivelyorganise and hold government to account. The result is a seriousabsence of formal or informal civil society oversight – or „downwardaccountabil<strong>it</strong>y‟ – of government actors.‘What we need is arevolution <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bomas.People need to start formingtrade unions, cooperatives,farmers groups, women’sgroups – at grass rootslevel. These groups are<strong>the</strong>re anyway, in some form,in any commun<strong>it</strong>y. So <strong>it</strong>’sjust a matter of building <strong>the</strong>ircapac<strong>it</strong>y; teaching <strong>the</strong>m howto make <strong>the</strong>ir ownregulations and how toadvocate.’Advisor to <strong>the</strong> Ministry ofAgriculture, Upper Nile, May 2011.The problem is fur<strong>the</strong>r exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>it</strong> is extremelydifficult for national NGOs or CSOs in South Sudan to accessinternational donor funds. This is due to a range of factors including lackof access to information on funding opportun<strong>it</strong>ies, cumbersomeapplication procedures, a requirement for aud<strong>it</strong>ed accounts, arequirement that operational support costs be shared between multiplegrants (when many national NGOs/CSOs have only one donor), orminimum grant sizes that are too large for most national NGOs/CSOs tomanage. 20 The exclusion of civil society <strong>from</strong> development assistanceruns counter to <strong>the</strong> comm<strong>it</strong>ment made by donors in <strong>the</strong> Accra Agendafor Action to „work w<strong>it</strong>h CSOs to provide an enabling environment thatmaximises <strong>the</strong>ir contributions to development‟ 21 – and lim<strong>it</strong>s <strong>the</strong> abil<strong>it</strong>yof national NGOs/CSOs to play a role both in service delivery and inpromoting/demanding good governance.Recommendations• Provide more substantial support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives that promotecommun<strong>it</strong>y participation in both human<strong>it</strong>arian and developmentassistance. „Commun<strong>it</strong>y driven development‟ models have in somecases proved successful in achieving sustainable results – howeverto maximise <strong>the</strong> chances of success such in<strong>it</strong>iatives should beclosely mon<strong>it</strong>ored, and where possible linked to governmentplanning processes. Whatever <strong>the</strong> model used, grant agreementsshould require (and be long enough to allow for) <strong>the</strong> genuineparticipation of men, women and children, and should be flexibleenough to be adapted in response to commun<strong>it</strong>y input.12

• Provide more substantial support for efforts aimed at streng<strong>the</strong>ningcivil society including women‟s, youth and fa<strong>it</strong>h-based groups. Thisshould include financial support for CSOs, and training forcommun<strong>it</strong>ies and CSOs on <strong>the</strong> roles and responsibil<strong>it</strong>ies ofgovernment and on strategies for engaging w<strong>it</strong>h local author<strong>it</strong>ies. 22The South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013 (SSDP) contains acomm<strong>it</strong>ment to training civil society on good governance, and <strong>the</strong>Government of South Sudan (GoSS) should be supported to fulfilthis comm<strong>it</strong>ment.• Ensure that South Sudan‟s new aid arch<strong>it</strong>ecture facil<strong>it</strong>ates nationalNGO/CSO access to international funds. This requires attention to<strong>the</strong> factors currently precluding access (financial reportingrequirements, lim<strong>it</strong>ed capac<strong>it</strong>y to cost-share, grant sizes, etc); andattention to building <strong>the</strong> capac<strong>it</strong>y of national NGOs/CSOs to subm<strong>it</strong>compet<strong>it</strong>ive proposals and meet donor requirements includingproperly accounting for funds received.13

4 Ensure an equ<strong>it</strong>able distribution ofassistanceThe Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development‟sPrinciples for Good International Engagement in Fragile States andS<strong>it</strong>uations (‘Fragile States Principles’) recognise <strong>the</strong> need to „avoidpockets of exclusion‟ and „aid orphans‟ – „states [or geographicalregions w<strong>it</strong>hin a country] where … few international actors are engagedand aid volumes are low.‟ 23Throughout <strong>the</strong> CPA interim period, much of <strong>the</strong> focus of developmentin South Sudan has been in Juba, and to a lesser extent, <strong>the</strong> ten statecap<strong>it</strong>als. As a result, today <strong>the</strong>re is significant and growing inequal<strong>it</strong>y:between Juba and <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> country; between urban and ruralareas; w<strong>it</strong>hin urban areas (such as between squatter areas andwealthier neighbourhoods); and between and w<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>the</strong> states. InEastern Equatoria, for example, Magwi county receives considerableinternational support, in part because <strong>the</strong> local leadership is welleducated and adept at advocating for support; while <strong>the</strong> counties ofLopa/Lafon and Kopoeta North, w<strong>it</strong>h comparable needs but harder toreach, receive l<strong>it</strong>tle. 24 Such an approach can lead to increasedmarginalisation, often of <strong>the</strong> poorest and most vulnerable, and risksreinforcing historical grievances. 25The issue is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> GoSS‟s own mechanism for <strong>the</strong>distribution of wealth. The Trans<strong>it</strong>ional Const<strong>it</strong>ution of <strong>the</strong> Republic ofSouth Sudan calls for an equ<strong>it</strong>able distribution among <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rnSudanese states and local governments 26 – but because of <strong>the</strong>unreliabil<strong>it</strong>y of population data, funds allocated for state and countycap<strong>it</strong>al expend<strong>it</strong>ure („block transfers‟) are spl<strong>it</strong> equally (not equ<strong>it</strong>ably)between each of <strong>the</strong> states and <strong>the</strong>n again between <strong>the</strong> counties. ThusJonglei, for example, gets roughly a third as much per cap<strong>it</strong>a asWestern Bahr el Gazal, while having to provide for a food insecurepopulation nearly six times as large. 27 Such an approach runs counterto <strong>the</strong> development model envisaged not only in <strong>the</strong> Trans<strong>it</strong>ionalConst<strong>it</strong>ution but also by <strong>the</strong> CPA, which recognised <strong>the</strong> „historicalinjustices and inequal<strong>it</strong>y in development between <strong>the</strong> different regionsof <strong>the</strong> Sudan‟, and called for wealth to be shared w<strong>it</strong>hout discriminationon any grounds. 28Recommendations• Ensure that international assistance is appropriately targeted so as topromote equ<strong>it</strong>able social and economic development. In determininggeographic focus areas, seek to avoid unintentional exclusionaryeffects – such as a disproportionate focus on easily accessible areas,or a focus on states or counties w<strong>it</strong>h strong leadership or betterinfrastructure. This requires substantially improved donorcoordination (including joint assessment and mon<strong>it</strong>oring), as well as14

frequent travel outside <strong>the</strong> cap<strong>it</strong>al for mon<strong>it</strong>oring and assessmentpurposes. The GoSS should also be supported to develop <strong>it</strong>s owncoordination capac<strong>it</strong>y – for example through programs such as <strong>the</strong>UNDP‟s Local Government Recovery Program.• Support <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFEP) todevelop a system for a more equ<strong>it</strong>able (and transparent) distributionof wealth between and w<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>the</strong> states. At a minimum, <strong>the</strong>allocation of block transfers to <strong>the</strong> counties should take into accountcounty populations, toge<strong>the</strong>r w<strong>it</strong>h o<strong>the</strong>r cr<strong>it</strong>eria such as povertylevels, <strong>the</strong> availabil<strong>it</strong>y of services and population dens<strong>it</strong>y. Donorsshould ensure that in <strong>the</strong> lead up to <strong>the</strong> next census, <strong>the</strong> SouthSudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation is supported toprovide <strong>the</strong> government w<strong>it</strong>h „up-to-date and accurate informationw<strong>it</strong>h which to plan <strong>the</strong> efficient and equ<strong>it</strong>able allocation of publicresources‟ 29 – as envisaged in <strong>the</strong> SSDP.15

5 Prior<strong>it</strong>ise <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable andensure social protectionGirl at repaired borehole, Leer Town. © Carolyn Gluck for <strong>Oxfam</strong>South Sudanese live in an environment in which livelihoods areconstantly under threat: by climatic shocks, by conflict, and by afluctuating global economy. Income shocks over <strong>the</strong> past year havebeen particularly harsh, and more than three million people throughout<strong>the</strong> country are e<strong>it</strong>her moderately or severely food insecure. 30Thousands of households engage in harmful coping strategies –including reducing food intake, selling productive assets, taking childrenout of school, and going into debt. 31 W<strong>it</strong>h food prices continuing to rise,an ongoing influx of returnees and secur<strong>it</strong>y continuing to deteriorate,food secur<strong>it</strong>y levels could easily decline fur<strong>the</strong>r – pushing more andmore households towards <strong>the</strong>se and o<strong>the</strong>r harmful coping strategies. 32Deteriorating food secur<strong>it</strong>y can lead to increased violence andinsecur<strong>it</strong>y, and exacerbates vulnerabil<strong>it</strong>ies. At <strong>the</strong> commun<strong>it</strong>y level, foodinsecur<strong>it</strong>y increases compet<strong>it</strong>ion for scarce resources; and at <strong>the</strong>16

household level, men who are frustrated by <strong>the</strong>ir inabil<strong>it</strong>y to provide for<strong>the</strong>ir families are more likely to resort to violence. 33 Women areexposed to fur<strong>the</strong>r violence as <strong>the</strong>y take on alternative livelihoodsactiv<strong>it</strong>ies, and <strong>the</strong> vulnerabil<strong>it</strong>y of children and o<strong>the</strong>r vulnerable groupsis exacerbated as spending on essential services is reduced.In a context of heightened vulnerabil<strong>it</strong>y, programs targeting groups w<strong>it</strong>hparticular needs (separated and unaccompanied children, persons w<strong>it</strong>hsevere medical cond<strong>it</strong>ions, persons w<strong>it</strong>h HIV/AIDS, survivors of genderbasedviolence, single heads of households, widows, and <strong>the</strong> elderlyand disabled) are all <strong>the</strong> more important. But in South Sudan suchprograms are scarcely available. Recent interviews carried out by <strong>the</strong>South Sudan protection cluster found that services to support separatedand unaccompanied children were available in just one third of areassurveyed, while services to support o<strong>the</strong>r vulnerable groups were evenscarcer. 34W<strong>it</strong>h a view to „empowering vulnerable groups and providingsafeguards for people living in extreme poverty‟, <strong>the</strong> SSDP states that„core policies on social protection … are being developed‟. 35Specifically, <strong>the</strong> GoSS aims to provide a „nation-wide child benef<strong>it</strong> cashtransfer‟ to households w<strong>it</strong>h children under six years; and to „have acomprehensive social protection system in place‟ by 2013. 36Social protection (defined by <strong>the</strong> Organisation for EconomicCooperation and Development as „policies and actions which enhance<strong>the</strong> capac<strong>it</strong>y of poor and vulnerable people to escape <strong>from</strong> poverty andenable <strong>the</strong>m to better manage risks and shocks … [including] socialinsurance, social transfers and minimum labour standards‟ 37 ) can play acr<strong>it</strong>ical role in protecting household assets in times of shock; and inmore prof<strong>it</strong>able times, empowering households to engage in riskier butmore prof<strong>it</strong>able activ<strong>it</strong>y. It can also leverage gains made in <strong>the</strong> socialsectors by empowering poor men and women to access services – forexample by enabling poor households to purchase books and uniformsso as to send <strong>the</strong>ir children to school, and to pay <strong>the</strong> transportationcosts necessary to access healthcare. 38 And perhaps most importantly,social protection can promote gender equ<strong>it</strong>y – because in times ofincome shock <strong>the</strong> burden of reduced household spending isdisproportionately borne by women. 39 More needs to be done tounderstand trad<strong>it</strong>ional social protection mechanisms and how externalactors can support such approaches.But social protection is not always effective in meeting <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong>most vulnerable – and in <strong>the</strong> design and implementation of socialprotection policies for South Sudan <strong>it</strong> will be cr<strong>it</strong>ical that lessons learnt<strong>from</strong> social protection programming around <strong>the</strong> world be taken intoaccount. In particular:• Social protection strategies must be gender-sens<strong>it</strong>ive, meaning that<strong>the</strong>y must be informed by a robust analysis of gender relations, andensure that increased household income is effectively allocated andresults in a streng<strong>the</strong>ned pos<strong>it</strong>ion for women. 4017

• Targeting strategies must be based on a sound poverty analysis andclearly matched to <strong>the</strong> purpose of social protection – meaning that if<strong>the</strong> purpose of social protection is to increase food secur<strong>it</strong>y, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>it</strong>will be appropriate to target <strong>the</strong> most food insecure households,whereas if <strong>the</strong> objective is to enable future generations to break free<strong>from</strong> poverty, <strong>the</strong>n social assistance such as child benef<strong>it</strong>s will bemost appropriate.• Inst<strong>it</strong>utional capac<strong>it</strong>y, across <strong>the</strong> range of ministries that have a rolein <strong>the</strong> design and implementation of social protection programs, iscr<strong>it</strong>ical to success. Also important are clearly defined ministerialresponsibil<strong>it</strong>ies, inter-ministerial coordination, and an implementationmechanism that allows for delivery by <strong>the</strong> „lowest possibleadministrative levels‟. 41• The issue of fiscal sustainabil<strong>it</strong>y must be analysed at <strong>the</strong> outsetwhen determining <strong>the</strong> scale and scope of social protection programs.Experience shows that sustainable financing will likely be a long termprocess requiring reallocation of domestic resources, domesticrevenue generation and well-coordinated international aid. 42It is important to note that even <strong>the</strong> best designed social protectionprograms do not replace <strong>the</strong> need for pro-poor social and economicpolicies, nor for appropriate investment in <strong>the</strong> social sectors. Nor do<strong>the</strong>y replace <strong>the</strong> need for specific interventions promoting <strong>the</strong> rights ofvulnerable groups; nor for livelihoods promotion programs. Experienceshows that w<strong>it</strong>hout complementary livelihoods activ<strong>it</strong>ies, socialassistance is unlikely to lift people out of poverty; 43 and w<strong>it</strong>houtinterventions aimed at <strong>the</strong> promotion of rights, can inadvertentlyexacerbate stigmatization. 44Recommendations• Support <strong>the</strong> GoSS to develop and introduce appropriate socialprotection policies and streng<strong>the</strong>n trad<strong>it</strong>ional mechanisms where<strong>the</strong>y exist. Consideration should be given to a range of instrumentsincluding child and disabil<strong>it</strong>y benef<strong>it</strong>s, and cash transfers targetingthose most vulnerable to food insecur<strong>it</strong>y. Policies must be informedby a sound poverty analysis, an understanding of <strong>the</strong> purpose ofsocial protection in South Sudan, and lessons learned <strong>from</strong> socialprotection programming elsewhere. Funding must be long-term,predictable and aligned w<strong>it</strong>h national policies, and particular attentionmust be paid to ensuring domestic fiscal sustainabil<strong>it</strong>y.• Ensure that support for social protection is accompanied byappropriate capac<strong>it</strong>y building for key ministries (MoFEP, Health,Education, and Gender, Child and Social Welfare) in <strong>the</strong> design anddelivery of social protection programs; and support <strong>the</strong> GoSS toclearly define ministerial responsibil<strong>it</strong>ies and to establish adecentralised delivery mechanism.18

• Advocate w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>the</strong> GoSS to increase <strong>it</strong>s budget allocation to <strong>the</strong>social sectors (<strong>the</strong> current allocation is well below regional norms 45 ),and ensure that donor support for social protection does not result ina corresponding reduction of support for essential services.• Provide more substantial financial and technical support to programstargeting vulnerable groups, including separated andunaccompanied children, <strong>the</strong> disabled and <strong>the</strong> elderly, single-headedhouseholds, widows and survivors of gender-based violence –noting that such programs are often most successful when designedand implemented in partnership w<strong>it</strong>h government ministries andwhen <strong>the</strong>y provide an integrated package of services (such aslivelihoods support, shelter and education). 4619

6 Support pro-poor, sustainablelivelihoods‘There is ample evidence toshow that economic growthis <strong>the</strong> single most importantfactor in reducing povertywhere <strong>it</strong> is accompanied bymeasures to improve humancap<strong>it</strong>al and ensure thatgrowth is both broad-basedand as equ<strong>it</strong>able aspossible. This underscores<strong>the</strong> importance of ensuringthat all segments of <strong>the</strong>population – children, youth,adults and older persons aswell as both <strong>the</strong> rural andurban poor – are enabled toparticipate in and to benef<strong>it</strong><strong>from</strong> a process of inclusivegrowth.’Government of <strong>the</strong> Republic ofSouth Sudan, South SudanDevelopment Plan.Desp<strong>it</strong>e <strong>the</strong> richness of South Sudan‟s natural resource base, <strong>the</strong> vastmajor<strong>it</strong>y of <strong>the</strong> population relies primarily on subsistenceagro/pastoralism. The formal economy, which accounts for almost all of<strong>the</strong> government‟s revenue but employs only a small proportion of <strong>the</strong>population, is overwhelmingly dependent on oil resources, which areexpected to be in decline by 2015. 47 Just four per cent of arable land iscultivated, <strong>the</strong> production of livestock and fish is just a fraction of <strong>the</strong>potential, and interstate trade and international exports are minimal. 48The scope for prof<strong>it</strong>able livelihoods throughout <strong>the</strong> country is enormous;<strong>the</strong> challenge is to ensure that <strong>the</strong> available resources are explo<strong>it</strong>ed in amanner that leads to improved food secur<strong>it</strong>y and a reduction in povertyacross South Sudan.The livelihoods profiles of <strong>the</strong> different states differ widely, <strong>from</strong> analmost exclusive reliance on agriculture in <strong>the</strong> southwest, to <strong>the</strong> purepastoralism of <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast. Livelihoods are constrained by differentfactors in different regions, but across <strong>the</strong> country a number of keychallenges can be identified:• The impact of insecur<strong>it</strong>y on almost every aspect of life in SouthSudan has been highlighted earlier in this paper, but <strong>it</strong> is essential tonote here too <strong>the</strong> inextricabil<strong>it</strong>y of <strong>the</strong> link between secur<strong>it</strong>y andlivelihoods. Insecur<strong>it</strong>y restricts access to markets, water sources,fields and grazing areas; disrupts seasonal labour migration; and isoften associated w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ft and/or destruction of crops andlivestock. As explained by one man in Yambio county, WesternEquatoria, „secur<strong>it</strong>y is a cond<strong>it</strong>ion for everything‟. 49• A significant major<strong>it</strong>y of returnees have no access to cultivatableland and do not own livestock. 50 Many rely on begging, borrowing or<strong>the</strong> sale of household assets, 51 placing enormous strain on hostcommun<strong>it</strong>ies. Relatively l<strong>it</strong>tle attention has been paid to medium tolong-term reintegration issues (including problems associated w<strong>it</strong>haccess to land for returnees, particularly female-headedhouseholds); 52 and returnees who have received livelihood supporthave often been provided only w<strong>it</strong>h agricultural inputs – desp<strong>it</strong>e <strong>the</strong>relatively small number w<strong>it</strong>h access to land, and <strong>the</strong> fact that manyhave lived for years in urban settings and have a variety ofpotentially explo<strong>it</strong>able, marketable skills.• In <strong>the</strong> months leading up to independence, restricted movementsubstantially affected livelihoods activ<strong>it</strong>y across <strong>the</strong> Sudan/SouthSudan border. Traders, farmers and nomadic tribes <strong>from</strong> Sudanwere prevented <strong>from</strong> exchanging commod<strong>it</strong>ies w<strong>it</strong>h South Sudanand <strong>from</strong> accessing lands trad<strong>it</strong>ionally used for cultivation andgrazing; and South Sudanese were prevented <strong>from</strong> migrating northfor seasonal labour and <strong>from</strong> selling fish and livestock to traders<strong>from</strong> Sudan. This affected incomes in South Sudan, increased <strong>the</strong>20

cost of production in Sudan, and resulted in a substantial increasein food prices. 53‘What <strong>the</strong>y produce, <strong>the</strong>ysell at give-a-way prices.’Advisor to <strong>the</strong> Ministry ofAgriculture, Western Equatoria• Finally, <strong>the</strong>re is a near complete absence of value-adding equipmentor technology – meaning that <strong>the</strong> potential for small-scalecommercial agriculture is virtually untapped. Wheat flour, maizeflour, sugar and palm oil, available in abundance in raw form, areimported <strong>from</strong> neighbouring countries. Western Equatoria, whichcould be feeding <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> country but instead imports flour, riceand fru<strong>it</strong> and vegetable products <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Democratic Republic ofCongo and Uganda, is a case in point.Box 1: Access to markets in <strong>the</strong> ‘Green Belt’In Western Equatoria, mangos lie rotting on <strong>the</strong> ground. As one farmerexplains, „<strong>the</strong>re‟s no market for <strong>the</strong>m here. If someone knew someone whocould come and buy <strong>the</strong>m and knew where to sell <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>y could do <strong>it</strong>.‟ 54The chairman of <strong>the</strong> Yambio Farmer‟s Association (YAFA) says „<strong>the</strong>re‟s noway to carry [<strong>the</strong> mangos] to ano<strong>the</strong>r place. How would you keep <strong>the</strong>m wellto reach that place?‟ He says that YAFA has a plan to buy a juicing machine,but that <strong>the</strong> plan „depends on money‟. In <strong>the</strong> meantime, traders import juicepacks <strong>from</strong> Uganda and sell <strong>the</strong>m in Yambio for 12 Sudanese pounds –enough for one family to buy meat for a week.Access to cred<strong>it</strong> is a commonly-c<strong>it</strong>ed problem. There‟s a micro-financeinst<strong>it</strong>ution in Yambio, but <strong>it</strong> doesn‟t give loans to farmers, which are regardedas long-term loans. YAFA recently sought a loan to purchase a truck, but <strong>the</strong>application was rejected. The truck would have enabled YAFA to transportproduce to Juba and elsewhere – charging members only a small fee formaintenance and fuel costs.The point is that while fru<strong>it</strong>s, vegetables and grains grow in abundance,almost every point of <strong>the</strong> „value chain‟ (connecting producer to consumer) isunder-developed. Farmers can‟t sell <strong>the</strong>ir crops locally because <strong>the</strong>re‟s nomarket, and <strong>the</strong>y can‟t afford to send <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> markets because <strong>the</strong>ydon‟t have enough to make <strong>it</strong> worth <strong>the</strong>ir while to pay for transport. Theycan‟t produce any more because <strong>the</strong>y can‟t afford to hire a tractor tocultivate larger areas; and <strong>the</strong>y can‟t get a loan to hire <strong>the</strong> tractor becauseloans aren‟t available to farmers. And even if you could get around all this,<strong>the</strong> produce probably wouldn‟t be compet<strong>it</strong>ive anyway because ofsubstandard processing and packaging. 55Recommendations• Provide more substantial support for small-scale agricultural (andpastoral/piscicultural) production. In add<strong>it</strong>ion to seeds and tools,focus on streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> private sector (for example throughsupport to seed multiplication and bulking centres) so that farmerscan access seeds and tools through functioning markets. O<strong>the</strong>rprior<strong>it</strong>ies include training in improved farming, fishing and animalhusbandry techniques; agricultural extension services; processingand packaging inputs and technology; and access to cred<strong>it</strong>.Assistance should in all cases be pro-poor (meaning that21

interventions must support, not exclude, smallholder production);must prior<strong>it</strong>ise vulnerable groups; and must be designed so as toensure <strong>the</strong> equ<strong>it</strong>able participation of both women and men.• Provide more substantial and better targeted livelihoods support inareas hosting large numbers of returnees based on an analysis of<strong>the</strong> different needs of women and men. Seeds, tools and training areappropriate for those w<strong>it</strong>h access to land, but for <strong>the</strong> landlessmajor<strong>it</strong>y, more innovative approaches are required. Returneesshould be supported to productively engage in local economies,utilising skills and experiences acquired during <strong>the</strong> war and in amanner appropriate to <strong>the</strong>ir new (often urban) environments. In allcases livelihoods support should be context-specific, based onmarket assessments, and relevant to <strong>the</strong> skills and assets alreadypossessed by beneficiaries.• Scale-up efforts to promote access to and ownership of land forreturnees, internally displaced persons and vulnerable groups. Thisshould include support for: <strong>the</strong> establishment of offices of <strong>the</strong> SouthSudan Land Commission in each state; <strong>the</strong> development of countyland author<strong>it</strong>ies and payam land councils; <strong>the</strong> development ofpolicies and procedures for rest<strong>it</strong>ution and compensation in relationto land taken during <strong>the</strong> civil war; and <strong>the</strong> establishment (orenhancement) of commun<strong>it</strong>y-based dispute resolution in<strong>it</strong>iatives.• Provide technical support for <strong>the</strong> Sudan/South Sudan bordercooperation policy – ensuring <strong>the</strong> free movement of persons andgoods for purposes of economic and social interaction. Specifically,support <strong>the</strong> GoSS in <strong>it</strong>s provisional comm<strong>it</strong>ment to ensure thatdecisions regarding border management are taken „at <strong>the</strong> levelnearest to <strong>the</strong>ir implementation‟, and that „<strong>the</strong> views and interests of<strong>the</strong> various stakeholders including … commun<strong>it</strong>y actors [are] takeninto account‟ in <strong>the</strong> management of border issues. 56• Recognising that livelihoods will be seriously constrained so long ascommun<strong>it</strong>ies continue to live in fear of violence, continue to supportin<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at improving local secur<strong>it</strong>y. These should includelocal peacebuilding in<strong>it</strong>iatives (implemented through establishedcommun<strong>it</strong>y structures), continued support for <strong>the</strong> demobilisation,disarmament and reintegration of former combatants, and programsto support and promote good governance, commun<strong>it</strong>y-orientedpolicing and access to both formal and trad<strong>it</strong>ional dispute resolutionmechanisms – in all cases based on commun<strong>it</strong>y-identified needs.22

7 Streng<strong>the</strong>n government capac<strong>it</strong>y– <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bottom upThe Trans<strong>it</strong>ional Const<strong>it</strong>ution of <strong>the</strong> Republic of South Sudan contains acomm<strong>it</strong>ment to <strong>the</strong> „decentralisation of decision-making in regard todevelopment, service delivery and good governance,‟ 57 and <strong>the</strong> LocalGovernment Act 2009 devolves responsibil<strong>it</strong>y for <strong>the</strong> provision of basicservices to „local government councils‟. 58 For most South Sudanese,<strong>the</strong>ir impressions of government are defined by <strong>the</strong>ir interaction w<strong>it</strong>h,and <strong>the</strong> qual<strong>it</strong>y of services provided by, county governments – and<strong>the</strong>se interactions are thus fundamental to building <strong>the</strong> leg<strong>it</strong>imacy of <strong>the</strong>new government.Desp<strong>it</strong>e this for much of <strong>the</strong> CPA interim period, efforts to buildgovernment capac<strong>it</strong>y have focused on central government inst<strong>it</strong>utions. 59The GoSS‟ Medium-Term Capac<strong>it</strong>y Building Strategy acknowledgesthat <strong>the</strong>re is „no decentralised policy for capac<strong>it</strong>y development‟, that„government revenue has not reached <strong>the</strong> state and county levels in asustained, efficient manner‟, and that „links between levels ofgovernment must be fur<strong>the</strong>r developed … through a redistribution ofhuman and material resources away <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> centre and towardsinst<strong>it</strong>utions in <strong>the</strong> states.‟ 60 Recent months have seen <strong>the</strong> beginnings ofa shift in focus (USAID‟s streng<strong>the</strong>ning governance project, and <strong>the</strong>Norwegian in<strong>it</strong>iative to bring in civil servants <strong>from</strong> neighbouringcountries to train/mentor South Sudanese civil servants, providepos<strong>it</strong>ive examples), but <strong>the</strong>re is a long way to go before localgovernment (county) councils can be expected to assume fullresponsibil<strong>it</strong>y for <strong>the</strong> provision of basic services.‘For six months, I haven’teven been able to send anemail <strong>from</strong> my own office toJuba. We’ve been askingand asking about having <strong>the</strong>VSAT fixed but no one’scome. I have to go to UNDPor UNICEF and use <strong>the</strong>irinternet. Even <strong>the</strong> simplestthings hold us up.’Senior state government official,June 2011.The task of building government capac<strong>it</strong>y at <strong>the</strong> county level facesenormous challenges. Many county departments lack <strong>the</strong>ir own officespace, many are reliant e<strong>it</strong>her on commercial buses or rides <strong>from</strong>NGOs for transportation, and few have access to adequatecommunications. Many have no access to computers, few have internetaccess, and <strong>the</strong> few who do have internet access may not know how touse <strong>it</strong>. In many cases county author<strong>it</strong>ies don‟t control <strong>the</strong>ir own finances,making <strong>it</strong> difficult for <strong>the</strong>m to undertake even <strong>the</strong> most basicdevelopment activ<strong>it</strong>ies. 61Attracting qualified staff to work in <strong>the</strong> counties is a particularlypersistent problem, as is <strong>the</strong> payment of staff salaries. In some casescounty government staff are not on <strong>the</strong> government payroll, and where<strong>the</strong>y are, salaries are often received late and sometimes not at all. Insome cases county officials are not even based in <strong>the</strong> county for which<strong>the</strong>y are responsible due to a lack of infrastructure – w<strong>it</strong>h obviousimplications for <strong>the</strong>ir abil<strong>it</strong>y to understand <strong>the</strong>ir const<strong>it</strong>uencies andprovide services based on real needs. 6223

‘There’s a school, but <strong>the</strong>reare no real teachers. Thereare two volunteer teachers –<strong>the</strong>y don’t receive a salary.Even if <strong>the</strong>re is a school and<strong>the</strong>re are students, you stillneed teachers <strong>the</strong>re to give<strong>the</strong>m knowledge. We’reworried that <strong>the</strong> teachers willget fed up and leave.’Male commun<strong>it</strong>y member, Jamamcounty, Upper Nile, May 2011.Box 2: The non-payment of teacher salariesFunds for county government salaries and operational costs are transferredas „cond<strong>it</strong>ional grants‟ <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> GoSS to state governments each month.The MoFEP has directed that upon receipt, <strong>the</strong> funds should be transferredimmediately <strong>from</strong> state to county treasuries and reflected in county budgets.But this is resisted by some states, and in <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong> funds areretained in state government treasuries.Where cond<strong>it</strong>ional grants for county governments are retained by <strong>the</strong> state,salaries for county government staff should be transferred on a monthlybasis <strong>from</strong> states to counties. In some cases salaries are transferred tocounty bank accounts; but where this is not possible (due to countyauthor<strong>it</strong>ies not having bank accounts), <strong>the</strong> cash is sent by road to <strong>the</strong>county. Information is <strong>the</strong>n passed to civil servants – if possible by phone,but where this is not possible, <strong>the</strong>n „manually‟ – that salaries are ready forcollection at <strong>the</strong> county headquarters. Civil servants <strong>the</strong>n have a lim<strong>it</strong>edperiod to collect <strong>the</strong>ir salaries.Teachers earn, on average, around 250 Sudanese pounds ($94) eachmonth. For teachers located in, say, <strong>the</strong> border areas of Eastern Equatoria,travelling to county headquarters will likely cost around 150 Sudanesepounds ($56), plus one or two days away <strong>from</strong> families. Even where salariesdo make <strong>it</strong> <strong>from</strong> state to county headquarters (often difficult in <strong>the</strong> rainyseason), and even if <strong>the</strong> information does <strong>the</strong>n reach <strong>the</strong> teacher, in manycases <strong>it</strong> is simply not feasible for staff to travel <strong>the</strong> distance to collect <strong>the</strong>irsalaries. 63Attracting staff to <strong>the</strong> counties and professionalising <strong>the</strong> payroll systemare cr<strong>it</strong>ical issues – but an even deeper and more difficult problem is <strong>the</strong>scarc<strong>it</strong>y of qualified staff throughout <strong>the</strong> country. As explained by oneJuba-based NGO staff, „some donors (and UN and NGOs) seem tothink that if a project or activ<strong>it</strong>y is short of staff, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> answer is tohire add<strong>it</strong>ional educated people and provide a b<strong>it</strong> of role-specifictraining. But <strong>the</strong>re simply aren‟t enough qualified people around andany such hiring is a zero-sum game. If an NGO hires someone good,<strong>the</strong>n that person isn‟t available for <strong>the</strong> government, or if a stategovernment hires someone good, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y‟re probably depriving acounty government of that person, and so on.‟ 64 It is a fundamentalchallenge that has not yet been adequately addressed by government,donors or implementing agencies.Recommendations• Support <strong>the</strong> GoSS in <strong>it</strong>s comm<strong>it</strong>ment to decentralising development,service delivery and governance. This should include: moresubstantial capac<strong>it</strong>y building for state and county author<strong>it</strong>ies; supportfor <strong>the</strong> GoSS to develop systems for ensuring that state governmentsare held accountable for funds received, and that county departmentsreceive sufficient resources to carry out <strong>the</strong>ir assigned responsibil<strong>it</strong>iesas well as control over (and training to manage) <strong>the</strong>ir own budgets;and support for <strong>the</strong> development of safeguards to ensure equ<strong>it</strong>abledistribution to <strong>the</strong> states and counties.24

• Provide more targeted support for in<strong>it</strong>iatives aimed at addressing keycapac<strong>it</strong>y gaps at <strong>the</strong> county level. This should include: training,mentoring and technical support; provision of funds; provision oftransport, office space and communications equipment; and supportfor <strong>the</strong> development of business management systems includinghuman resources and payroll. Donors should adopt a harmonised,inter-agency approach, and <strong>the</strong> prior<strong>it</strong>ies, roles and responsibil<strong>it</strong>ies ofdifferent actors engaged in capac<strong>it</strong>y building should be clearlydefined.• Continue to explore innovative solutions for increasing <strong>the</strong> number ofqualified staff throughout <strong>the</strong> country. Possible in<strong>it</strong>iatives couldinclude: programs aimed at harnessing <strong>the</strong> skills of <strong>the</strong> diaspora;specialised internships; student or professional exchange programsw<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>the</strong> region; and enhanced support for (and coordination of)technical and vocational education and training programs in SouthSudanese inst<strong>it</strong>utions.25