Ecology and Management of Oak Woodlands on Tejon Ranch ...

Ecology and Management of Oak Woodlands on Tejon Ranch ...

Ecology and Management of Oak Woodlands on Tejon Ranch ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

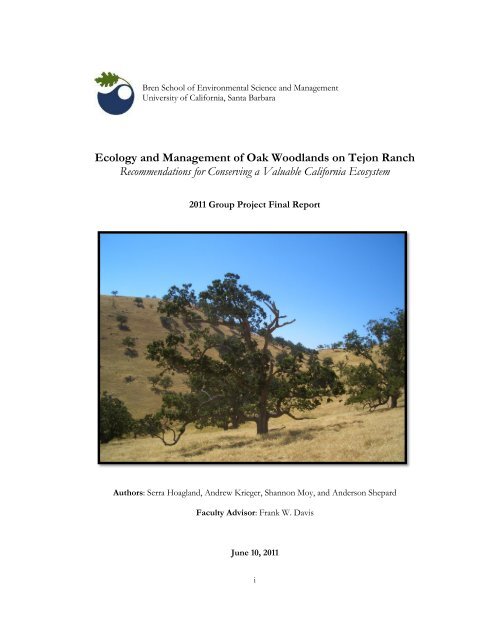

Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Santa Barbara<str<strong>on</strong>g>Ecology</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for C<strong>on</strong>serving a Valuable California Ecosystem2011 Group Project Final ReportAuthors: Serra Hoagl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Andrew Krieger, Shann<strong>on</strong> Moy, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Anders<strong>on</strong> ShepardFaculty Advisor: Frank W. DavisJune 10, 2011i

Page Intenti<strong>on</strong>ally Left Blank

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Ecology</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for C<strong>on</strong>serving a Valuable California EcosystemAs authors <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this Group Project report, we are proud to archive it <strong>on</strong> the Bren School‘s websitesuch that the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our research are available for all to read. Our signatures <strong>on</strong> the documentsignify our joint resp<strong>on</strong>sibility to fulfill the archiving st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ards set by the Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>._________________________________ANDERSON SHEPARD_________________________________SHANNON MOY_________________________________ANDREW KRIEGER_________________________________SERRA HOAGLANDThe missi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> is to producepr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essi<strong>on</strong>als with unrivaled training in envir<strong>on</strong>mental science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> management who will devotetheir unique skills to the diagnosis, assessment, mitigati<strong>on</strong>, preventi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> remedy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theenvir<strong>on</strong>mental problems <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> today <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the future. A guiding principle <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the School is that theanalysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>mental problems requires quantitative training in more than <strong>on</strong>e discipline <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>an awareness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the physical, biological, social, political, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ec<strong>on</strong>omic c<strong>on</strong>sequences that arisefrom scientific or technological decisi<strong>on</strong>s.The Group Project is required <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all students in the Master‘s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> (MESM) Program. It is a three academic quarter activity in which small groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>students c<strong>on</strong>duct focused, interdisciplinary research <strong>on</strong> the scientific, management, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> policydimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a specific envir<strong>on</strong>mental issue. This Final Group Project Report is authored byMESM students <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> has been reviewed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> approved by:________________________________FRANK W. DAVIS, PH.D.June 2011

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe would like to thank the following individuals for their support <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> guidance throughout thedurati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our project.Dr. Frank Davis – Faculty Advisor, Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>Dr. Mike White – Client, C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Science Director, Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancyTom Mal<strong>on</strong>ey – Client, Executive Director, Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancyDr. Trish Holden – Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>, UCSBDr. Lee Hannah – Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>, UCSBDr. Bruce Kendall – Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>, UCSBDr. Maki Ikegami – Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>, UCSBDr. Claudia Tyler – Assistant Research Biologist, ICESS, UCSBSoapy Mulholl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> – Executive Director, Sequoia Riverl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s TrustHilary Dustin – C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Director, Sequoia Riverl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s TrustNicole Molinari – PhD C<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>idate, EEMB, UCSBKaren Stalhler – PhD C<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>idate, EEMB, UCSBThomas Reed – PhD C<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>idate, EE, UCSBRusty Brown – UCSB Library Imagery SpecialistDeborah Lupo – UCSB Library Imagery SpecialistDan Gira – More Mesa Preservati<strong>on</strong> Coaliti<strong>on</strong>Dr. Heather Scheck – Santa Barbara County Plant PathologistBob Stafford – Wildlife Biologist, Chimineas <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fish & GameDavid Clendenen – Resource Ecologist, Wind Wolves Preserve, The Wildl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s C<strong>on</strong>servancySheri Spiegal – PhD C<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>idate, Range <str<strong>on</strong>g>Ecology</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lab, UC BerkeleyJennifer Browne – Operati<strong>on</strong>s Manager, Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancyChris A. Niemela – C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Scientist, Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancyRob Peters<strong>on</strong> – Senior Director <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Resource Planning, Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> CompanyBiogeography Lab – Bren School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g>, UCSBiv

ABSTRACTIn 2008 the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> Company <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a group <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong>s signed thel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>mark Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Use Agreement which permanently protected178,000 ecologically valuable acres <strong>on</strong> the <strong>Ranch</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> created the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancywhose missi<strong>on</strong> is to ―preserve, enhance, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> restore the native biodiversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecosystemvalues <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Tehachapi Range for the benefit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California‘s futuregenerati<strong>on</strong>s‖. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the C<strong>on</strong>servancy‘s primary tasks is the creati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a <strong>Ranch</strong>-Wide<str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Plan (RWMP) which will support the C<strong>on</strong>servancy‘s missi<strong>on</strong>. The goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thisproject was to study oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> the ranch <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> make oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> managementrecommendati<strong>on</strong>s to be included in the RWMP. Through a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> field work, dataanalyses, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> modeling we characterized the ranch‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, compared their structure toother California oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, quantified oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> growth rates, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>modeled how climate change will influence future distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. We foundthat blue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak populati<strong>on</strong>s are slowly declining <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> predicted that climatechange will result in significant shifts in suitable habitats for blue, valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oaks. Giventhese threats we recommend that the C<strong>on</strong>servancy employ protective cages around seedlings<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> saplings in areas that are likely to remain climatically suitable over the next 50 years.v

Page Intenti<strong>on</strong>ally Left Blankvi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> is the largest c<strong>on</strong>tiguous private property in California <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> encompasses 270,000acres at the c<strong>on</strong>vergence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> four major ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s: the Mojave Desert, the Central Valley, theSierra Nevada, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Transverse Ranges. The ranch is home to rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> endemic species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> communities including extensive foothill <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>tane oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s,all located within 100 miles <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Los Angeles.In 2008, the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> Company, owner <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a coaliti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>organizati<strong>on</strong>s signed the l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>mark Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Use Agreement (theAgreement). Under the Agreement, the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> Company may develop 30,000 acres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> unc<strong>on</strong>tested by the c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong>s while 178,000 acres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ranchare committed to permanent c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>. In March <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2011 an additi<strong>on</strong>al 62,000 c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>acres were secured. The Agreement also established the n<strong>on</strong>-pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>it Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancy(the C<strong>on</strong>servancy) whose missi<strong>on</strong> is to ―preserve, enhance, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> restore the native biodiversity<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecological values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Tehachapi Range for the benefit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California‘sfuture generati<strong>on</strong>s‖. In pursuit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this missi<strong>on</strong> the C<strong>on</strong>servancy is charged with developing a<strong>Ranch</strong>-Wide <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Plan (RWMP) that will employ an adaptive management strategy inorder to enhance c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> values <strong>on</strong> the <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> maintain current l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> uses permittedunder the Agreement such as hunting, cattle grazing, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> filming. The goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our project is toassess the ecological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> make managementrecommendati<strong>on</strong>s for the RWMP.Our research included three m<strong>on</strong>ths <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> field data collecti<strong>on</strong> during the summer <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2010. Groupmembers A. Krieger <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> S. Moy collected tree, understory, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> soil data in 105 blue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>black oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> plots. These data were used to characterize Tej<strong>on</strong>‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>were used in other modeling exercises <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> analyses. Table i below lists the primary methodsthat this project employed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their associated purposes:Table i - Overview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> analyses d<strong>on</strong>e in this study.Method/AnalysisPurposeTimber Survey Map Validati<strong>on</strong>Mutual Informati<strong>on</strong> Analysis (MIA)Species Envir<strong>on</strong>mental GradientModeling: HyperNicheMaxEnt ModelingHistorical Photo AnalysisComparative AnalysisQuantify map uncertainty <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the degree to which the Timber SurveyMap accurately classifies the distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oaks <strong>on</strong> the <strong>Ranch</strong>Stratified r<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>om sampling for selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> plotsModeled species distributi<strong>on</strong>s by using species importance valuescalculated from relative basal area <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> relative species abundanceClimate suitability forecasting for three focal speciesQuantify change over time (i.e. populati<strong>on</strong> growth rate)Statewide <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> management comparis<strong>on</strong>svii

To learn how to best manage oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>, we addressed five guidingquesti<strong>on</strong>s:What are the current extent, distributi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong><strong>Ranch</strong>?According to a 1980 timber survey map that has the best informati<strong>on</strong> available regarding oakdistributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>, 6% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ranch is covered by blue oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 7% is coveredby valley oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2% is covered by black oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Our plot levelcharacterizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary vegetati<strong>on</strong> agreed with the much larger timber survey polyg<strong>on</strong>s57.7% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the time. Blue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oaks occupy distinct envir<strong>on</strong>mental locati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> theranch. Blue oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are most dominant at lower elevati<strong>on</strong>s between 500 meters <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1000meters <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> elevati<strong>on</strong> while black oaks dominate woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s at elevati<strong>on</strong>s above 1200 meters.Valley oaks at Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> exhibit a bi-modal elevati<strong>on</strong>al distributi<strong>on</strong>, reaching maximumabundance between 400 to 600 meters <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1400 to 1800 meters <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> elevati<strong>on</strong>. Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> iswithin the southern extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ranges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. As a result oakwoodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> the ranch occupy higher elevati<strong>on</strong>s than others throughout California. Blue oak<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> understories are dominated by grasses while black oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>understory is composed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a mixture <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> grass <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrubs.How do the structures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> compare to those in the rest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>California?We compared st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> basal area <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> tree diameter at breast height (DBH) in our plots to thoserecorded in a statewide sample <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> U.S. Forest Service Inventory <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Analysis (FIA) plots <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>data reported by Allen-Diaz et al. in chapter 12 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Terrestrial Vegetati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California (Bolsinger1988). Tej<strong>on</strong>‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, particularly valley oak <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are better stockedthan those throughout California. Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>‘s blue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak trees also have largerDBHs than those throughout the state.How are the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> changing over time <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is there aregenerati<strong>on</strong> problem?We compared archival air photos from 1952 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2009 to determine how the oak populati<strong>on</strong>swere changing over time. The estimated annual populati<strong>on</strong> growth rate for blue oaks rangedfrom 0.996 to 0.999. Populati<strong>on</strong> growth rate ranged from 0.997 to 1.000 for valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 0.998 to1.000 for black oaks. While these growth rates are <strong>on</strong>ly slightly below <strong>on</strong>e, oak populati<strong>on</strong>s willsee a decrease <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> about 9% over the next 50 years at the current rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline.How do we expect the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> to be impacted by climatechange?Many plant communities are predicted to shift in resp<strong>on</strong>se to climate change <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>sare expected to lose habitat in future climates (Kueppers et al. 2005). We modeled future oakdistributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the ranch with species distributi<strong>on</strong> models using a moderate-high (A2) carb<strong>on</strong>emissi<strong>on</strong> scenario <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> two general circulati<strong>on</strong> models. These climate change models assume ac<strong>on</strong>tinued increase in CO 2 emissi<strong>on</strong>s throughout the 21 st century, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> predict a 2.5° C to 4.5° Cincrease in temperature over the same time period (Cubasch et al. 2001, Cayan et al. 2008). Forthe state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, <strong>on</strong>e model predicts a slightly wetter future (+ 8% change in annualprecipitati<strong>on</strong>), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>e predicts a slightly drier future (- 28% change in annual precipitati<strong>on</strong>)(Cayan et al. 2008). We found a general decline in climatic suitability for oaks <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>between now <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mid-century <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> further reducti<strong>on</strong>s by the end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the century. The overalltrend is movement upslope <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> toward north facing aspects. Our results showed similarviii

c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s for both models <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> for all species. Of the three species modeled, blue oaks showedthe most significant loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> climatically suitable habitat: 71%-80% reducti<strong>on</strong> by mid-century, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>92%-93% reducti<strong>on</strong> by the end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the century. For black oak the models predict a reducti<strong>on</strong> insuitable habitat <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 61%-78% by mid-century, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 90%-100% by the end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the century. Valleyoaks are predicted to lose 19%-56% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their suitable habitat <strong>on</strong> the <strong>Ranch</strong> by mid-century, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>78%-94% by the end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the century. Despite these drastic reducti<strong>on</strong>s in climatically suitablehabitat, the abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> varied topography <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> microclimates <strong>on</strong> the ranch may provide habitatrefugia for oak species, effectively buffering these populati<strong>on</strong>s from severe habitat loss due toclimate change.How are current l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> management practices affecting Tej<strong>on</strong>’s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s?Hunting, fire management, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grazing impact oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> the ranch. Depending <strong>on</strong> theintensity, durati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> seas<strong>on</strong>ality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> grazing, livestock can influence seedling recruitment, bothdirectly by way <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> browsing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> indirectly by reducing the competiti<strong>on</strong> from annual grasses.Grazing can also alter soil properties including bulk density <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> infiltrati<strong>on</strong> rates. Fire influencesoak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by altering fuel loads, understory assemblage <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> soilproperties. Hunting impacts oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by affecting deer, elk, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> feral pig populati<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>the understory community. While our research did not quantify the impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> grazing, fire <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>hunting <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, we recommend the C<strong>on</strong>servancy establish experimental plotsin order to determine how different management regimes impact Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Recommendati<strong>on</strong>sBlue, valley, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> are all undergoing a slow but significantdecline, threatening losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> about 9% over the next 50 years. The most cost effective way tostabilize oak populati<strong>on</strong>s is to deploy small, circular cages around naturally occurring saplings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>seedlings in order to exclude browsing ungulates. This protecti<strong>on</strong> should allow seedlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>saplings to escape the browse layer within roughly five years. If current demographic ratespersist, this process will need to be repeated every five years to stabilize oak populati<strong>on</strong>s.Given that climate change is predicted to influence future oak distributi<strong>on</strong>, we recommend thatthe C<strong>on</strong>servancy target its restorati<strong>on</strong> efforts in areas where suitable oak habitat is projected tobe stable over the next 50 years. Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> uncertainties about whether future climate <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong><strong>Ranch</strong> will be wetter or dryer, we recommend that managers target restorati<strong>on</strong> efforts in areaswhere both the ‗warmer-wetter‘ climate model <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‗warmer-drier‘ climate model used in thisstudy predict to be stable climatically suitable habitat over the next 50 years.In order to stabilize oak populati<strong>on</strong>s, we calculated that managers will have to protect blue oakseedlings or saplings at a density <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 8.49 trees/ha within the blue oak target area, 0.21 trees/hawithin the valley oak target area, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1.62 within the black oak target area.ix

TABLE OF CONTENTSAcknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... ivAbstract .......................................................................................................................................................... vExecutive Summary ................................................................................................................................... viiTable <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>tents ......................................................................................................................................... xList <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Figures ............................................................................................................................................. xiiList <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tables .............................................................................................................................................. xiiiList <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boxes .............................................................................................................................................. xiiiProject Significance ...................................................................................................................................... 1Background ................................................................................................................................................... 3<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Diversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Ecology</str<strong>on</strong>g> ................................................................................................ 3Diversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Distributi<strong>on</strong> ................................................................................................................ 3Basic Biology ....................................................................................................................................... 3<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife ............................................................................................................................... 3<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> ..................................................................................................... 3Climate Change ................................................................................................................................... 5<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Regenerati<strong>on</strong> ............................................................................................................................... 5Policy ......................................................................................................................................................... 6California <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s Laws <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ordinances Applicable to Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> ....................... 6Federal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> State Laws Relevant to Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>Ranch</strong>-Wide <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Plan .. 6Project Introducti<strong>on</strong> ..................................................................................................................................... 9Q1: What is the current extent, distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong><strong>Ranch</strong>? .......................................................................................................................................................... 13Data Collecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Map Validati<strong>on</strong> .................................................................................................. 13Species Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Gradient Modeling ...................................................................................... 15Understory Characterizati<strong>on</strong> ................................................................................................................ 18Q2: How do the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> compare to those in the rest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California? .... 21Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Results: Tej<strong>on</strong> vs. statewide oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ......................................................... 21Valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s .................................................................................................................... 21Black <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ..................................................................................................................... 22Blue <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ....................................................................................................................... 24x

Q3: How are the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> changing over time, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is there a regenerati<strong>on</strong>problem? .......................................................................................................................................................27Historical Photo Analysis .....................................................................................................................27Methods ..............................................................................................................................................28Results .................................................................................................................................................28Sources <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Error ................................................................................................................................29Nurse Plants Promote Valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Regenerati<strong>on</strong> ..............................................................................30Numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Seedlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Saplings ....................................................................................................31Q4: How do we expect the oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> to be impacted by climate change? .35Significance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> climate change for oak species .................................................................................35Species-climate Forecasting ..................................................................................................................35Q5: How are current l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> management practices affecting Tej<strong>on</strong>‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s? .....................43Hunting ....................................................................................................................................................43Grazing ....................................................................................................................................................43Fire ...........................................................................................................................................................44Restorati<strong>on</strong> ..............................................................................................................................................45<str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s ..............................................................................................................47Future Research......................................................................................................................................51Appendix ......................................................................................................................................................53Appendix I – Field Methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Additi<strong>on</strong>al Analyses ....................................................................53Site Selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Field Methods ...................................................................................................53Vegetati<strong>on</strong> Plot Methodology .........................................................................................................54Soil Compacti<strong>on</strong> ................................................................................................................................57Understory, Seedlings, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Saplings ..............................................................................................58Bolsinger methods ............................................................................................................................60Appendix II: Historical Photo Analysis .............................................................................................61Populati<strong>on</strong> Growth Rate Calculati<strong>on</strong>s ...........................................................................................61Appendix III: Species Distributi<strong>on</strong> Models .......................................................................................63Overview ............................................................................................................................................63Methods ..............................................................................................................................................64State-wide training data comparis<strong>on</strong>: .............................................................................................69Appendix IV: Comparative <str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Analysis ..........................................................................71General Notes: ..................................................................................................................................71References ....................................................................................................................................................74xi

LIST OF FIGURESFigure i – Locati<strong>on</strong> map. ............................................................................................................................. 9Figure ii – Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> allocati<strong>on</strong>s. ............................................................................................... 10Figure 1.1 – Vegetati<strong>on</strong> plots map. .......................................................................................................... 13Figure 1.2 – Species envir<strong>on</strong>mental gradient model (1). ...................................................................... 15Figure 1.3 – Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue oak. ..................................................................................................... 16Figure 1.4 – Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak .................................................................................................... 16Figure 1.5 – Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak. .................................................................................................. 17Figure 1.6 – Species envir<strong>on</strong>mental gradient model (2). ...................................................................... 18Figure 1.7 – Blue oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> understory compositi<strong>on</strong> by category. .................................................... 18Figure 1.8 – Valley oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> understory compositi<strong>on</strong> by category. .................................................. 19Figure 1.9 – Black oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> understory compositi<strong>on</strong> by category. ................................................... 19Figure 1.10 – Shrub <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grass cover <strong>on</strong> black oak plots. ..................................................................... 20Figure 2.1 – Tej<strong>on</strong> vs. State-wide valley oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> basal area. ............................................................ 21Figure 2.2 – Tej<strong>on</strong> valley oak size histogram. ........................................................................................ 22Figure 2.3 – Tej<strong>on</strong> vs. State-wide black oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> basal area. ............................................................. 23Figure 2.4 – Tej<strong>on</strong> black oak size histogram. ......................................................................................... 23Figure 2.5 – Tej<strong>on</strong> vs. State-wide blue oak st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> basal area. ............................................................... 24Figure 2.6 – Tej<strong>on</strong> blue oak size histogram. .......................................................................................... 25Figure 3.1 – Historical photo analyses overview map. ......................................................................... 27Figure 3.2 – Historical photo analyses example. ................................................................................... 28Figure 3.3 – Scatter plot showing populati<strong>on</strong> growth rates for sample photo st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ..................... 29Figure 3.4 – Rabbit brush valley oak plots understory compositi<strong>on</strong>. ................................................ 30Figure 3.5 – Total abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue, black, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oaks <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>. .............................. 32Figure 3.6 – Tej<strong>on</strong> vs. State-wide relative stocking rates for seedlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> saplings ....................... 33Figure 4.1 – Climatic suitability models spatial c<strong>on</strong>gruence ................................................................ 37Figure 4.2 – Predicted range shifts for blue oak due to future climate change. ............................... 39Figure 4.3 – Predicted range shifts for black oak due to future climate change.. ............................ 40Figure 4.4 – Predicted range shifts for valley oak due to future climate change .............................. 41Figure 6.1 – Valley oak c<strong>on</strong>sensus mid-century stable <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unstable ranges ..................................... 48Figure 6.2 – Blue oak c<strong>on</strong>sensus mid-century stable <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unstable ranges. ....................................... 49Figure 6.3 – Black oak c<strong>on</strong>sensus mid-century stable <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unstable ranges ...................................... 50Figure I.1 – Understory transect data sheet. .......................................................................................... 55Figure I.2 – Tree survey data sheet. ......................................................................................................... 56Figure I.3 – Calibrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> penetrometer <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> bulk density measurements ....................................... 57Figure I.4 – Relati<strong>on</strong>ship between percent bare ground <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> penetrometer readings ..................... 58Figure I.5 – Seedling densities as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrub cover.. ............................................................. 59Figure I.6 – Sapling densities as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrub cover. ................................................................ 60Figure II.1 – Additi<strong>on</strong>al examples <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> historical photo analysis sample plots. .................................. 62Figure III.1 – MaxEnt resp<strong>on</strong>se curves. ................................................................................................. 66Figure III.2 – MaxEnt-modeled climatic suitability for blue oak. ...................................................... 66Figure III.3 – MaxEnt-modeled climatic suitability for black oak ..................................................... 67Figure III.4 – MaxEnt-modeled climatic suitability for valley oak ..................................................... 67Figure III.5 – HyperNiche-modeled distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak .......................................................... 68Figure III.6 – HyperNiche-modeled distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue oak ............................................................ 68Figure III.7 – Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> local vs. state-wide training data for species distributi<strong>on</strong> models .. 70xii

LIST OF TABLESTable i – Overview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> analyses d<strong>on</strong>e in this study. ................................................ viiTable 1.1 – Total coverage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue, black, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>. .....................................14Table 1.2 – Timber survey map validati<strong>on</strong> .............................................................................................14Table 2.1 – Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> statewide valley oak basal area <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> DBH. ..............22Table 2.2 – Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> statewide black oak basal area <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> DBH................24Table 2.3 – Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> statewide blue oak basal area <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> DBH. ................25Table 3.1 – Demographic rates calculated from the historical photo analysis. .................................29Table 3.2 – Density <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak seedlings within blue, black, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s .......................31Table 3.3 – Density <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak saplings within blue, black, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s .........................32Table 3.4 – Density <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult trees in blue valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> blak oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ........................................32Table 4.1 – Selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>mental predictors for climate modeling. .........................................36Table 4.2 – Blue, black, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak resp<strong>on</strong>ses to climate change. ................................................38Table 4.3 – Predicted replacement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> current oak dominants by future oak dominants. ...............42Table 6.1 – Recommendati<strong>on</strong> specifics for active oak restorati<strong>on</strong> .....................................................51Table I.1 – T-test table for analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seedling/sapling densities <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> understory compositi<strong>on</strong>. ..58Table III.1 – Envir<strong>on</strong>mental predictor correlati<strong>on</strong> matrices ...............................................................65Table III.2 – Cross-validated AUC results for MaxEnt model runs ..................................................65Table IV.1 – <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> specific management practices employed elsewhere in the regi<strong>on</strong>. .71LIST OF BOXESBox 3.1 – Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stocking rates for oak seedlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> saplings between Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>the rest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California. ..................................................................................................................................33Box 4.1 – Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data resoluti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> predictive modeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> species distributi<strong>on</strong> for oaks <strong>on</strong>Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>. ................................................................................................................................................37xiii

Page Intenti<strong>on</strong>ally Left Blankxiv

PROJJECT SIGNIFICANCE<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g>s cover extensive areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the California l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape from coastal shrubs to foothillwoodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s to m<strong>on</strong>tane forests, but in the past 200 years oak cover has been drastically reduceddue to human development, including more than 1 milli<strong>on</strong> acres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oaks lost in the past 50 years(Brussard et al. 2004, Giusti et al. 2005). Today 20 oak species still cover about 17 milli<strong>on</strong> acres<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the California l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape (Giusti et al. 2005).California‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s face a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> threats. Perhaps the most well studied threat to oakwoodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s is comm<strong>on</strong>ly referred to as the oak ―regenerati<strong>on</strong> problem‖ (Tyler et al. 2006,Griffin 1971, 1976, Bolsinger 1988, Brown & Davis 1991, Whipple et al. 2010). A widespreadlack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak regenerati<strong>on</strong> has been well documented in California (Tyler et al. 2006). However,some research suggests that no regenerati<strong>on</strong> problem exists (Tyler et al. 2006). The extensiveuse <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s for cattle grazing has frequently been cited as the cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theregenerati<strong>on</strong> problem (Giusti et al. 2005). Cattle browse oak seedlings, eat acorns, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> compactthe soil, making it difficult for seedlings to germinate. According to Mahall et al. (2005) grazingis the most pervasive anthropogenic disturbance in oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, savannas, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grassl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s inCalifornia. Another threat to oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s is sudden oak death (Phytopthora ramorum). Suddenoak death was first detected in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1990s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> has since spread asfar south as Big Sur <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> as far north as Mendocino County. While the pathogen has not beendetected <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>, California Bay Laurel (Umbellularia californica) is a known carrier <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thedisease <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is present <strong>on</strong> the <strong>Ranch</strong>, heightening c<strong>on</strong>cerns. Development has historically been athreat to oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. From 1945 to 1988 it was estimated that 1.2 milli<strong>on</strong> acres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>hardwoods, primarily blue <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> valley oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, were lost in California (Bolsinger 1988).Many oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exist <strong>on</strong> private l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that are well suited for housing or agriculture. In theSan Joaquin Valley it is estimated that 95% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> riparian oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have been c<strong>on</strong>verted toagricultural use in the last 100 to 150 years (Kelly et al. 2005).Threats to oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are currently being addressed by a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> organizati<strong>on</strong>s employinga range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> strategies. Most sweeping is the California <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Act, a state law thatprotects oaks from development by requiring their replacement if oaks are removed fordevelopment. In additi<strong>on</strong>, 41 counties in California have their own oak protecti<strong>on</strong> ordinances.Private c<strong>on</strong>servancies <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> trusts have also played an important role in oak c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>.Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California operates the Integrated Hardwood Range<str<strong>on</strong>g>Management</str<strong>on</strong>g> Program whose goal is to c<strong>on</strong>serve hardwood forests in California including oakwoodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.The Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancy has a unique opportunity to sustainably manage a large,c<strong>on</strong>tiguous block <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most scenic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecologically valuable oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s inCalifornia. The <strong>Ranch</strong> supports roughly 82,000 acres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue oak, valley oak, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak,cany<strong>on</strong> oak, interior live oak, white oak, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mixed oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Appelbaum et al. 2010, USFish & Wildlife Service 2009) that are permanently protected under the Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Use Agreement. Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>‘s oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are particularly valuablebecause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their locati<strong>on</strong> at the crossroads <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the1

California Transverse Ranges making them a waypoint for wildlife migrating between these tworegi<strong>on</strong>s. This c<strong>on</strong>nectivity also has significant climate change adaptati<strong>on</strong> implicati<strong>on</strong>s as it willallow animal species to migrate <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> communities to shift northward in resp<strong>on</strong>se to awarmer climate.2

BACKGROUNDOAK WOODLAND DIVERSITY AND ECOLOGYDiversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Distributi<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Quercus spp.) dominate California‘s l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> play an important role in the culture,history, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the state (Pavlik 1991, FRAP 2002, Giusti et al. 2005, Kelly et al. 2005).California is home to 20 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 89 known species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak in the US, 7 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which are endemic tothe state (Nix<strong>on</strong> 2002). FRAP (2002) estimates that oaks cover at least <strong>on</strong>e-sixth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the state(>17 milli<strong>on</strong> acres), in mostly privately owned, low elevati<strong>on</strong> foothill woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>cover has sharply declined over the last century due to the expansi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> agriculture, rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s,<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> urban <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> rural development (Bolsinger 1988).Basic BiologyThe oak species in California are generally l<strong>on</strong>g-lived species; some documented to be over 600years old (Pavlik 1991). Seed germinati<strong>on</strong> generally occurs in resp<strong>on</strong>se to fall or winter rains<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <strong>on</strong>ce established, many species can take between 20 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 30 years to develop their flowering<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> reproductive capacities (Giusti et al. 2005). <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are wind-pollinated <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> flower in the earlyspring when the new leaves are forming. Depending <strong>on</strong> the species, acorns will mature in theFall <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the same year (e.g., valley oak, blue oak) or the Fall <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d year (e.g., black oak).Acorn crops are thought to be quasi-cyclical, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> timing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mast years varies by species (Giustiet al. 2005). <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in California vary c<strong>on</strong>siderably in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tree density <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> canopycover. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, with 10-60% tree canopy cover <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grassy ground cover (FRAP 2002,Barbour et al. 2007), grow <strong>on</strong> a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> soil types <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> climates <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> typically occur inelevati<strong>on</strong>al b<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s below m<strong>on</strong>tane forests (Pavlik 1991).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s provide some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the richest wildlife habitat <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California‘s vegetati<strong>on</strong>types (Pavlik 1991, Brussard et al. 2004). Of the 632 species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> terrestrial vertebrates found inthe state, over half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> them use oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s for cover, reproducti<strong>on</strong>, or forage (Giusti et al.2005). The structural diversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s provides diversity in wildlife habitats, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> theasynchr<strong>on</strong>ous producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acorns across individuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> species provides a food source thatcan last for over four m<strong>on</strong>ths in the fall when grasses <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> other forage are in short supply(Pavlik 1991, Giusti et al. 2005, Koenig et al. 2009). Studies show that the timing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a mast crop<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak trees is directly correlated to reproductive success <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a multitude <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds(Pavlik 1991, Koenig et al. 2009). Other studies have shown that in October, a single mule deermay eat as many as 300 acorns per day (Pavlik 1991).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>There are 10 species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> two recognized inter-specific hybrids <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak found <strong>on</strong> Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong>(Tej<strong>on</strong> <strong>Ranch</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servancy 2010):Q. agrifolia – coast live oakQ. berberidifolia – scrub oakQ. chrysolepis – cany<strong>on</strong> live oak3

Q. douglasii – blue oakQ. garryana var. breweri – brewer oakQ. john-tuckeri – tucker‘s oakQ. kelloggii – black oakQ. lobata – valley oakQ. wislizeni var. frutescens – interior scrub oakQ. wislizeni var. wislizeni – interior live oakQ. x alvordiana – alvord oakQ. x morehus – oracle oak<str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> communities studied for this report are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten referred to as ―hardwood rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.‖ Theterm ―rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>‖ indicates that livestock grazing is the dominant current or historical l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> use.Hardwood rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s encompass all communities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hardwood species ranging from sparselypopulated savannahs to densely populated forests. However, for simplicity we will refer to thecommunities studied as ―oak woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s‖ for the rest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this report. The critical ecological rolethat these woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s play in the ecosystem makes their management a top priority. Blue, valley<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black oak biology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecology is summarized below:Blue <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>sBlue oaks (Q. douglasii) are endemic to California, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> dominate over half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the state‘swoodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Pavlik 1991). They generally grow 30 – 40 feet tall with a diameter at breastheight (DBH) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 10 – 25 inches (Giusti et al. 2005). Blue oaks are found up to 4,000 feet inelevati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> are the most comm<strong>on</strong> woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> oak species in California. These trees arewinter deciduous but are also facultatively drought-deciduous, meaning that they can droptheir leaves mid-growing seas<strong>on</strong> if drought c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s become too stressful (Pavlik 1991).This unique adaptati<strong>on</strong> has allowed them to occupy some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the hottest <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> driest, n<strong>on</strong>desertclimates in the state. They are adapted to poor soils <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> are comm<strong>on</strong> in foothillsbordering interior valleys. Blue oaks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten form m<strong>on</strong>o-specific woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s with sparse,grassy understories (annual bromegrass, wild oats, fiddleneck, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> foxtail). Associati<strong>on</strong>s withtrees <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrubs such as foothill pine, cany<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> interior live oak, juniper, white-leafmanzanita, c<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>feeberry, pois<strong>on</strong> oak, ceanothus, buckbrush, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> California buckeye are notuncomm<strong>on</strong> (Borchert et al. 1991, Pavlik 1991, Brussard et al. 2004).Valley <str<strong>on</strong>g>Oak</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>sAlso endemic to California, valley oaks (Q. lobata) are arguably the largest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all the oaks inthe United States. They have been known to grow over 100 feet tall, with a DBH <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> up to 7feet (Pavlik 1991). They typically grow below 2,000 feet in elevati<strong>on</strong>, but they have beenfound up to 6,000 feet when deep soils <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> available water tables allow (Giusti et al. 2005).Valley oaks are phreatophytic, meaning that they get their water from belowground sources<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> are not directly dependent <strong>on</strong> precipitati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> other surface water sources. They do,however, require fairly deep <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> rich soils, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> are found in riparian areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> floodplains,alluvial fans <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> flats, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> upl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> terraces <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> plateaus (Giusti et al. 2005). Valley oaks mostcomm<strong>on</strong>ly have very open understories composed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> perennial grasses, butoccasi<strong>on</strong>ally may include shrubs such as pois<strong>on</strong> oak, toy<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>feeberry (Brussard et al.2004). Valley oaks were <strong>on</strong>ce widely distributed throughout much <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, but theirextent has been greatly reduced due to displacement by agriculture <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> urban <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ruraldevelopment <strong>on</strong> prime lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> real estate (Pavlik 1991, Appelbaum et al. 2010), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> givenpopulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> climate change predicati<strong>on</strong>s, their range is anticipated to decrease even moreover the next century (Grivet et al. 2008).4