Neoplastic Fixation to the Prevertebral ... - ResearchGate

Neoplastic Fixation to the Prevertebral ... - ResearchGate

Neoplastic Fixation to the Prevertebral ... - ResearchGate

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

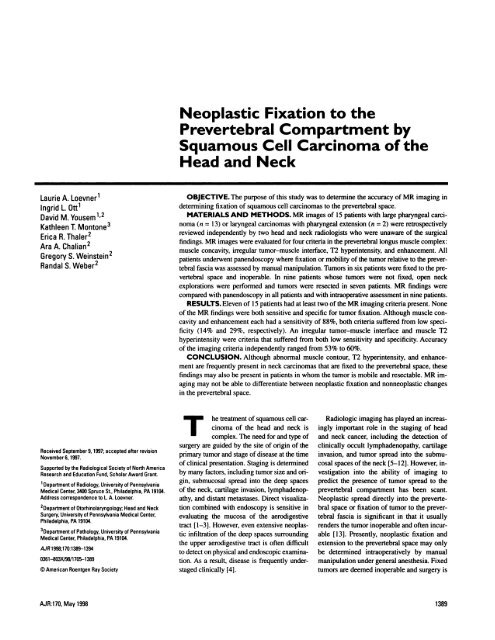

<strong>Neoplastic</strong> <strong>Fixation</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Prevertebral</strong> Compartment bySquamous Cell Carcinoma of <strong>the</strong>Head and NeckLaurie A. Loevner1Ingrid L 0111David M. Yousem1’2Kathleen 1. Mon<strong>to</strong>ne3Erica R. Thaler2Ara A. Chalian2Gregory S. Weinstein2Randal S. Weber2OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this study was <strong>to</strong> determine <strong>the</strong> accuracy of MR imaging indetermining fixation of squamous cell carcinomas <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral space.MATERIALS AND METHODS. MR images of 15 patients with large pharyngeal carcinoma(n = 13) or laryngeal carcinomas with pharyngeal extension (n = 2) were retrospectivelyreviewed independently by two head and neck radiologists who were unaware of <strong>the</strong> surgicalfindings. MR images were evaluated for four criteria in <strong>the</strong> prevertebral longus muscle complex:muscle concavity, irregular tumor-muscle interface, T2 hyperintensity, and enhancement. Allpatients underwent panendoscopy where fixation or mobility of <strong>the</strong> tumor relative <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralfascia was assessed by manual manipulation. Tumors in six patients were fixed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralspace and inoperable. In nine patients whose tumors were not fixed, open neckexplorations were performed and tumors were resected in seven patients. MR findings werecompared with panendoscopy in all patients and with intraoperative assessment in nine patients.RESULTS. Eleven of 15 patients had at least two of <strong>the</strong> MR imaging criteria present. Noneof <strong>the</strong> MR findings were both sensitive and specific for tumor fixation. Although muscle concavityand enhancement each had a sensitivity of 88%, both criteria suffered from low specificity(14% and 29%, respectively). An irregular tumor-muscle interface and muscle T2hyperintensity were criteria that suffered from both low sensitivity and specificity. Accuracyof <strong>the</strong> imaging criteria independently ranged from 53% <strong>to</strong> 60%.CONCLUSION. Although abnormal muscle con<strong>to</strong>ur, T2 hyperintensity, and enhancementare frequently present in neck carcinomas that are fixed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral space, <strong>the</strong>sefindings may also be present in patients in whom <strong>the</strong> tumor is mobile and resectable. MR imagingmay not be able <strong>to</strong> differentiate between neoplastic fixation and nonneoplastic changesin <strong>the</strong> prevertebral space.Received September 9, 1997; accepted after revisionNovember 6, 1997.Supported by<strong>the</strong> Radiological Society of North AmericaResearch and Education Fund, Scholar Award Grant1 Department of Radiology, University of PennsylvaniaMedical Center, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104.Address correspondence <strong>to</strong> L A. Loevner.2Department of O<strong>to</strong>rhinolaryngology, Head and NeckSurgery, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center,Philadelphia, PA 19104.3Department of Pathology, University of PennsylvaniaMedical Center, Philadelphia, PA 19104.AiR 1998;170:1389-13940361-803X/98/1705-1389© American Roentgen Ray SocietyT he treatment of squamous cell carcinomaof <strong>the</strong> head and neck iscomplex. The need for and type ofsurgery are guided by <strong>the</strong> site of origin of <strong>the</strong>primary tumor and stage of disease at <strong>the</strong> timeof clinical presentation. Staging is determinedby many fac<strong>to</strong>rs, including tumor size and origin,submucosal spread in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> deep spacesof <strong>the</strong> neck, cartilage invasion, lymphadenopathy,and distant metastases. Direct visualizationcombined with endoscopy is sensitive inevaluating <strong>the</strong> mucosa of <strong>the</strong> aerodigestivetract [1-3]. However, even extensive neoplasticinfiltration of <strong>the</strong> deep spaces surrounding<strong>the</strong> upper aerodigestive tract is often difficult<strong>to</strong> detect on physical and endoscopic examination.As a result, disease is frequently understagedclinically [4].Radiologic imaging has played an increasinglyimportant role in <strong>the</strong> staging of headand neck cancer, including <strong>the</strong> detection ofclinically occult lymphadenopathy, cartilageinvasion, and tumor spread in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> submucosalspaces of <strong>the</strong> neck [5-12]. However, investigationin<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> ability of imaging <strong>to</strong>predict <strong>the</strong> presence of tumor spread <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>prevertebral compartment has been scant.<strong>Neoplastic</strong> spread directly in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralspace or fixation of tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralfascia is significant in that it usuallyrenders <strong>the</strong> tumor inoperable and often incurable[13]. Presently, neoplastic fixation andextension <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral space may onlybe determined intraoperatively by manualmanipulation under general anes<strong>the</strong>sia. Fixedtumors are deemed inoperable and surgery isAJR:170, May 1998 1389

Loevner et ai.aborted. Therefore, it would be extremelyvaluable <strong>to</strong> be able <strong>to</strong> reliably determine <strong>the</strong>presence or absence of prevertebral fixationby preoperative imaging.The purpose of this study was <strong>to</strong> determine<strong>the</strong> usefulness of MR imaging in detectingneoplastic spread <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralspace in patients with advanced oropharyngeal,hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer.To do this, MR imaging findings were comparedwith observations during panendoscopyand open neck exploration.Materiais and MethodsThe MR images of 57 patients with primarypharyngeal orlaryngeal cancer seen in a 3-year penod(1993-1996) in <strong>the</strong> head and neck cancer centerat our institution were retrospectively reviewed.The MR images were evaluated for preservation of<strong>the</strong> prevertebral fat between <strong>the</strong> tumor and <strong>the</strong> prevertebralmusculature (longus colli-longus capitiscomplex). The retropharyngeal fat plane is readilyidentified on unenhanced Ti-weighted MR imagesbecause of its hyperintensity relative <strong>to</strong> surroundingtissues in <strong>the</strong> neck (muscle and lymphoid tissue)(Fig. 1). This fat plane at <strong>the</strong> tumor-muscleinterface was obliterated in 20 patients; however,five patients were eliminated from <strong>the</strong> study becauseno clinical or intraoperative assessment wasavailable. The MR images of <strong>the</strong> remaining 15 patients(nine men, six women), who had a mean ageof62 years (range, 48-78 years), were selected forinclusion in this study. All patients had squamouscell carcinoma with <strong>the</strong> site of origin in <strong>the</strong>oropharynx (n = 8), <strong>the</strong> hypopharynx (n = 5), and<strong>the</strong> larynx with extension <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> pharynx (n = 2).All patients underwent panendoscopy under gencmlanes<strong>the</strong>sia <strong>to</strong> assess for <strong>the</strong> presence or absenceof tumor fixation <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralcompartment. Patients thought <strong>to</strong> be surgical candidatesduring panendoscopy underwent openneck exploration and surgical resection.All examinations were performed with a Signal.5-T scanner (General Electric Medical Systems,Milwaukee, WI) using an anterior-posterior volumeneck coil (Medical Advances, Madison, WI).The MR imaging pro<strong>to</strong>col consisted of standardspin-echo sagittal Il-weighted images (TRITErange, 600/I 1-17) followed by fat-suppressed axialfast spin-echo T2-weighted (‘FR rangelFE,3500-4000/90) and axial spin-echo TI-weightedimages (600/1 1-17). Images of <strong>the</strong> neck extendedfrom <strong>the</strong> level of <strong>the</strong> cavernous sinus <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> thoracicinlet. After <strong>the</strong> administration of 0.1 mmoi/kg gadopentetate dimeglumine IV (Magnevist;Schering, Berlin, Germany) axial spin-echo TIweightedimaging was repeated using <strong>the</strong> same parametersas <strong>the</strong> unenhanced scans. Fast spin-echoand contrast-enhanced studies were obtained with<strong>the</strong> application of frequency-selective fat-saturationtechniques. For <strong>the</strong> saginal Tl-weighted localizingMR images, a slice thickness of 5 mmwith a gap of 1 mm and a 30-cm field of view wereused. For all o<strong>the</strong>r sequences, a slice thickness of 5mm with interleaved images was used. O<strong>the</strong>r imagingparameters included one or two excitations,24- <strong>to</strong> 26-cm field of view, a 256 x 128 matrix forsagittal and contrast-enhanced Tl-weighted images,and a 256 x 192 matrix for axial unenhancedTl- and T2-weighted images.Retrospective image analysis was perfonnedindependently by two head and neck radiologistswho were unaware of <strong>the</strong> surgical findings. AllMR images were evaluated for <strong>the</strong> presence or absenceof <strong>the</strong> following findings in <strong>the</strong> prevertebrallongus muscle complex: concavity of <strong>the</strong> prevertebralmuscles, irregular or serrated muscular bordersat <strong>the</strong> tumor-muscle interface, abnormal T2signal intensity of <strong>the</strong> muscle, and enhancement of<strong>the</strong> muscle.The MR findings were correlated with findingson panendoscopy, at which time fixation or mobilityof <strong>the</strong> tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musculature was determinedby digital palpation and manipulation of<strong>the</strong> mass. Tumors found <strong>to</strong> be fixed on panendoscopywere deemed inoperable. Those masses determined<strong>to</strong> not be fixed by manual manipulationunderwent open neck exploration. Resection wasaborted in patients in whom <strong>the</strong> tumor was found <strong>to</strong>be fixed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartment during surgery.In those patients without evidence of fixation,<strong>the</strong> tumors were resected and compared with findingsof <strong>the</strong> final his<strong>to</strong>logic examination. Specifically,<strong>the</strong> margins of <strong>the</strong> surgical specimens werestudied retrospectively by a head and neck pathologist<strong>to</strong> ensure that no tumor extended <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> borderwith <strong>the</strong> prevertebral space.The data were analyzed <strong>to</strong> determine <strong>the</strong> sensitivity,specificity, accuracy, and positive and negativepredictive values of each criterion. Interobserveragreement regarding image interpretation was basedon kappa analysis.ResultsSurgicalFindingsIn six patients, tumors were fixed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralstructures on manual manipulationduring panendoscopy and were considered inoperable.During open neck exploration in <strong>the</strong>remaining nine patients, two were found <strong>to</strong>have tumor fixed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musculatureand surgery was aborted (one of <strong>the</strong>se patientsalso had intraoperative biopsy-provenprevertebral muscle invasion). In <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r patientwhose tumor was found <strong>to</strong> be fixed duringopen neck exploration, a 3-week delayoccurred between panendoscopy and surgery.This patient had a poorly differentiated carcinoma,and it is possible that <strong>the</strong> developmen<strong>to</strong>ffixation might be explained by rapid intervalgrowth. In <strong>the</strong> remaining seven patients, extirpationof <strong>the</strong> tumors was performed, and <strong>the</strong>macro- and microscopic margins of <strong>the</strong> surgicalspecimens were free of tumor.MRFindingsFig. 1.-Normal ana<strong>to</strong>my in 46-year-old man.A, Off midline sagittal Ti-weighted MR image (600/17 hR/TEl; section thickness, 5 mm) shows prevertebral compartmen<strong>to</strong>f perivertebral space demarcated by precervical retropharyngeal fat seen as hyperintense linearband (arrows). Note longus muscle complex (L).B, Axial Ti-weighted MR image (600/17; section thickness, 5 mm) obtained at level of oropharynx shows prevertebralcompartment demarcated by precervical retropharyngeal fat (arrows). Note longus muscle complex (LI,internal carotid artery (asterisk), and jugular vein lv).The MR images of 15 patients each hadfour imaging criteria assessed for a <strong>to</strong>tal of 60interpretations. The observers agreed in 57 of60 readings (ic = .88) and resolved <strong>the</strong> threediscrepant interpretations by consensus. Theindividual criteria for prevertebral fixation (ipsilateralmuscle concavity, irregular muscular1390 AJR:170, May 1998

MR Imaging of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of <strong>the</strong> Head and Neck‘revertebral Muscle <strong>Fixation</strong>: Comparison of Criteria Revealed by MRmaging In IS Patients,: ,. Criteria #{149}!SensitivitySpecificityPPV(%) NPV(%) Accuracy88 -14545053lrregularborders-’T2 hyerintensity ]Enha1’nement’ 4P’ ‘!.t ..62 L50 tt 4f-. 88 43432956505850 4367534760Note.-PPV = positive predictive value, NPV = negative predictive value.border at <strong>the</strong> tumor-muscle interface. muscleT2 hyperintensity, and muscle enhancement)suffered from both low specificity (range, 14-43%) and low accuracy (range. 53-60%) due<strong>to</strong> a high false-positive rate (Tables I and 2).Although <strong>the</strong> presence of muscle concavityand enhancement each showed 88% sensitivityfor prevertebral fixation, high false-positiverates resulted in low specificities (14% and29%, respectively). No correlation existed betweenprevertebral muscle fixation and <strong>the</strong>presence or absence of ei<strong>the</strong>r irregular muscularborders at <strong>the</strong> tumor-muscle interface orT2 hyperintensity (Figs. 2 and 3). The presenceof enhancement of <strong>the</strong> muscle was <strong>the</strong>most likely predic<strong>to</strong>r of tumor fixation (positivepredictive value, 58%) and was <strong>the</strong> mostaccurate criterion at just 60%. The correlationbetween <strong>the</strong> number of positive MR criteriaand <strong>the</strong> presence of fixation was poor. Somepatients with few positive criteria had fixation.Even in <strong>the</strong> seven patients with all fbur criteriapresent, only three had tumors that had prevertebralfixation on panendoscopy.Although <strong>the</strong> sample size of patients was<strong>to</strong>o small <strong>to</strong> apply a grading system for eachof <strong>the</strong> MR criteria, we did note that in patientswith fixation of tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartment<strong>the</strong> degree of T2 hyperintensity andenhancement within <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musclewas usually more prominent than in those patientswithout fixation.Discussion*Fig. 2.-49-year-old woman with primary carcinoma of oropharynx.A, Sagittal Ti-weighted MR image (600/17 ETA/TEl; section thickness, 5 mm) shows attenuation of right retropharyngealfat plane (arrows).B, Axial Ti-weighted MR image (600/17; section thickness, 5 mm) shows attenuation of right retropharyngeal fatplane (arrows) and mild enlargement of right longus muscle complex; compare with normal left side (LI. Note retropharyngealnodal mass (N).C, Axial T2-weighted MR image (3500/90; section thickness, 5 mm) reveals abnormally high signal intensity in Iongusmuscle complex (arrows).D, Contrast-enhanced axialTi-weighted MR image(600/i7; sectionthickness, 5 mm)shows enhancement of prevertebralmuscle (arrows). On intraoperative panendoscopy, tumor was found <strong>to</strong> be fixed <strong>to</strong> prevertebral musculature,making resection impossible.The prevertebral space is <strong>the</strong> anterior compartmen<strong>to</strong>f <strong>the</strong> perivertebral space. It is locatedbehind <strong>the</strong> retropharynx. investedanteriorly by a layer of fat and <strong>the</strong> deep cervicalfascia. The prevertebral space. encapsulatedby <strong>the</strong> deep layer of <strong>the</strong> deep cervicalfascia, contains a fat plane that is located between<strong>the</strong> two layers of <strong>the</strong> precervical fascia,<strong>the</strong> anterior prevertebral muscles (longus capitis,longus colli, rectus capitis anterior. andrectus capitis lateralis), <strong>the</strong> paraspinal musculature,and <strong>the</strong> vertebral bodies ( 14, 151 (Fig.I ). The musculus longus colli runs along <strong>the</strong>ventral surface of <strong>the</strong> vertebral bodies, extendingfrom <strong>the</strong> atlas <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> third or fourth vertebralbody. The musculus longus capitis arisesfrom <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> occipital bone and cxtends<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> anterior tubercles of <strong>the</strong> transverseprocesses of <strong>the</strong> third through sixth vertebrae.The longus colli and capitis muscles are <strong>the</strong>most vulnerable of <strong>the</strong> prevertebral muscles <strong>to</strong><strong>the</strong> spread of disease processes by virtue of<strong>the</strong>ir proximity and contiguity <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> pharyn-AJR:170, May 1998 1391

Loevner et al.Fig. 3-59-year-old woman with cancer of right oropharynx. <strong>Prevertebral</strong> invasion was suspected on basis of MR findings; however, intraoperatively, mass was not fixed<strong>to</strong> prevertebral structures and tumor was resected. Final his<strong>to</strong>logy revealed no evidence of tumor in surgical margins.A, Axial Ti-weighted MR image (600/17 ETRITEI; section thickness, 5 mm) shows large oropharyngeal mass (M) with obliteration offat between mass and prevertebral muscle.B, Axial contrast-enhanced Ti-weighted MR image (600/il; section thickness, 5 mm) reveals concavity of longus muscle complex (arrowhead) and muscle enhancement(arrows).C. Axial 12-weighted MR image (3500/90; section thickness, 5 mm) shows concavity of prevertebral muscle complex (arrowhead) and abnormal signal intensity (arrow).geal mucosal and retropharyngeal spaces. respectively[15, 16J. Although <strong>the</strong> deep cervicalfascia is a relatively resilient barrier <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> cxtensionof disease processes from <strong>the</strong> pharyngealmucosal and <strong>the</strong> deep nonmucosal spacesof <strong>the</strong> anterior neck, spread of disease includinginfectious and neoplastic processes mayoccur [15-17].Spread of tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartmentin <strong>the</strong> form of frank neoplastic invasionof <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musculature mayoccur. However, prevertebral extension mayalso be manifested by fixation of tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>prevertebral fascia without violation of <strong>the</strong>fascia or by tumor penetration through thisfascia but without direct extension in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>muscle. In head and neck cancer, any form ofprevertebral extension (including only fixation<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral fascia) is significant in thatit often renders <strong>the</strong> tumor inoperable and <strong>the</strong>patient incurable because surgeons are unable<strong>to</strong> obtain tumor-free surgical margins. Theprevertebral musculature is intimately associatedwith and interdigitates with <strong>the</strong> fascia of<strong>the</strong> prevertebral column. Hence, resection of<strong>the</strong> prevertebral muscle is difficult, dangerous,and unlikely <strong>to</strong> achieve complete resection of<strong>the</strong> gross tumor. In addition, partial surgicaldebulking of macroscopic tumor is associatedwith a poor clinical and functional outcome,In patients with squamous cell carcinoma of<strong>the</strong> pharynx at risk for prevertebral space invasionwho are o<strong>the</strong>rwise surgical candidates (noencasement of <strong>the</strong> internal carotid artery andno intracranial perineural extension through<strong>the</strong> skull base foramina), determination of tumorfixation <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartmentis presently made by digital manipulation onpanendoscopy under general anes<strong>the</strong>sia, If unequivocalfixation of <strong>the</strong> tumor exists, open cxplorationis often not necessary. O<strong>the</strong>rwise,open neck exploration is usually performedthrough <strong>the</strong> side of <strong>the</strong> neck not involved by<strong>the</strong> primary tumor, If both sides of<strong>the</strong> neck appear<strong>to</strong> be involved by tumor, <strong>the</strong> side with lessdisease is used for access. The technique involvesretraction of <strong>the</strong> carotid sheath and itscontents laterally and rotation of <strong>the</strong> larynxmedially. Then a finger is run superiorly <strong>to</strong> infenorlyin <strong>the</strong> plane anterior <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebralmuscle <strong>to</strong> determine if <strong>the</strong> tumor is fixed, If <strong>the</strong>tumor appears adherent <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> deep cervicalfascia, but not through it, some head and neckoncology surgeons will resect <strong>the</strong> fascia with<strong>the</strong> tumor. In some cases, a biopsy of regionsof suspicion in <strong>the</strong> muscle may be performed.and <strong>the</strong> sample is evaluated by frozen section<strong>to</strong> determine if <strong>the</strong> muscle has been invaded bytumor [ 1 31. Iftumor extension through <strong>the</strong> prevertebralfascia <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle is found. surgeryis aborted and patients are treated with radiation<strong>the</strong>rapy or combined radiation and chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy.If fl() direct evidence of tumorextension exists, extirpative surgery is performed.Although <strong>the</strong> possibility of microinvasioncannot he excluded until <strong>the</strong> finalhis<strong>to</strong>logy is reported. this is of less concern <strong>to</strong><strong>the</strong> surgeon because most patients are treatedwith radiation <strong>the</strong>rapy after surgery.Imaging plays a critical role in <strong>the</strong> staging ofhead and neck cancer including detection oflymphadenopathy, cartilage invasion. and tumorspread in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> submucosal spaces of <strong>the</strong>neck [5-I 2. 18-22 . The goal of <strong>the</strong> head andneck radiologist is not only <strong>to</strong> help direct <strong>the</strong>appropriate surgery for a patient with cancer butalso <strong>to</strong> determine which tumors are surgicallyunresectable. Assessment of <strong>the</strong> prevertebralspace is vital in this regard; however, little radiologicinvestigation has been done <strong>to</strong> determineif imaging findings exist that wouldindicate <strong>the</strong> presence or absence of neopla.sticextension <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartment. In astudy by Righi et al. [ 131. CT scans in 29 patientswith T3 and T4 pharyngeal carcinomaswere retrospectively reviewed by two neuroradiologistsand compared with operative findingsduring open neck exploration. In 1 7 patients,<strong>the</strong> CT scans were interpreted as negative forneoplastic spread <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musclesusing <strong>the</strong> criterion of preservation of <strong>the</strong> fatplane between <strong>the</strong> tumor and <strong>the</strong> muscle. Intraoperatively.three of <strong>the</strong>se I 7 patients werefound <strong>to</strong> have prevertebral invasion and surgerywas aborted. Hence, maintenance of <strong>the</strong> precervicalfat plane correctly predicted absence ofprevertebral involvement 82ck of <strong>the</strong> time. Thepreoperative CT scans of I 2 patients were interpretedas suggestive of prevertebral invasion on<strong>the</strong> basis of <strong>the</strong> obliteration of <strong>the</strong> fat plane between<strong>the</strong> tumor and <strong>the</strong> prevertebral muscleand asymmetric enlargement of <strong>the</strong> musclecomplex contiguous with <strong>the</strong> tumor. Three of<strong>the</strong>se patients (25c4 ) had involvement of <strong>the</strong>prevertebral space on intraoperative assessment.The renlaining nine patients in this groupunderwent resection, and, in three, microscopictulilor along <strong>the</strong> deep margin of <strong>the</strong> surgical1392 AJR:ilO, May 1998

MR Imaging of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of <strong>the</strong> Head and NeckFig. 4-52-year-old man with cancer of right oropharynx (tumor also involves right superior alveolus and retromolartrigone).A, Axial Ti-weighted MR image (600/il ITRITEI; section thickness, 5 mm) shows large oropharyngeal mass (M)compressing prevertebral compartment with concavity of muscle complex and irregular tumor-muscle interface(arrows).B, Axial 12-weighted MR image (3500/85; section thickness, 5 mm) acquired at same axial level as A shows similarfindings along prevertebral compartment. No signal intensity abnormality is seen in longus muscles. Tumor wasfreely mobile during surgery with tumor-free margins on his<strong>to</strong>logic examination of resected specimen.specimen was present on final his<strong>to</strong>logy; however,<strong>the</strong> prevertebral muscle fliscia was intactand uninvolved on direct inspection. Overall,this study suggests that CT suffers from lowsensitivity and low specificity in revealing prevertebralspace invasion.In <strong>the</strong> present study. MR findings were correlatedwith intraoperative assessment in 15patients with large pharyngeal or laryngeal primarytumors that obliterated <strong>the</strong> prevertebralfat such that <strong>the</strong> tumors appeared contiguouswith <strong>the</strong> prevertebral muscles (Figs. 4 and 5).The study by Righi et al. I 131 suggested thatmaintenance of <strong>the</strong> precervical fat plane on CTcorrectly predicted absence of macroscopicprevertebral involvement 82% of <strong>the</strong> time.With <strong>the</strong> improved soft-tissue resolution ofMR imaging and its multiplanar capabilities.<strong>the</strong> accuracy in predicting preservation of <strong>the</strong>precervical flit could potentially be higher.None<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> surgeons at our institution believethat preservation of this fat plane on imagingin <strong>the</strong> absence of o<strong>the</strong>r indica<strong>to</strong>rs ofinoperability warrants evaluation by panendos-COf))’ or surgical exploration even in <strong>the</strong> eventthat occasionally a tumor may he found <strong>to</strong> beunresectable during surgery.In this study. MR images were analyzed for<strong>the</strong> presence or absence of ipsilateral muscleconcavity. irregular tumor-muscle interface.abnormal T2 hyperintensity in <strong>the</strong> muscle. andmuscle enhancement. At least two of<strong>the</strong>se imagingfindings were present in I I of<strong>the</strong> 15 patients,and none of’ <strong>the</strong>se findings individually01’ <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r were consistently reliable in distinguishingthose patients with prevertebral cxtension(eight) from those without (seven)(Tables 1 and 2). Although <strong>the</strong> sample size ofpatients was <strong>to</strong>o small <strong>to</strong> apply a grading systemfor each of <strong>the</strong> MR criteria. we did notethat in patients with fixation of tumor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>prevertebral compartment <strong>the</strong> degree of T2hyperintensity and enhancement within <strong>the</strong>prevertebral muscle was usually more prominentthan in those patients without fixation.The presence of muscle enhancement was <strong>the</strong>most sensitive (88%) and <strong>the</strong> most accurate(60%) criterion for tumor fixation, but it wasnot an accurate indica<strong>to</strong>r of neoplastic spread.We speculate that a reactive inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry infiltrationproduced by <strong>the</strong> squamous cell carcinomaof <strong>the</strong> neck may account for <strong>the</strong> muscleT2 hyperintensity or enhancement. Some basisfor this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis can be found in <strong>the</strong>musculoskeletal literature 1231. Musculoskeletalneoplasms, tumor invading muscle, andnonneopla.stic muscle edema may be hyperintenseon T2-weighted images due <strong>to</strong> increasedwater content and may show enhancement aftercontrast material administration [23, 24]. Astudy by Lang et al. 1241, who attempted <strong>to</strong>distinguish peritumoral edema from tumor,suggested that <strong>the</strong>se entities may be differentiatedby dynamic scanning and spatial mappingof instantaneous enhancement rates.These authors found that viable tumor showedgreater and more rapid increases in T I -weighted signal intensity after contrast materialadministration than perineopla.stic edema,which showed lower and more gradual increasesin signal intensity. The applicability ofMR imaging in <strong>the</strong> head and neck remains <strong>to</strong>be determined.In conclusion, using <strong>the</strong> current MR techniquesdescribed herein, MR imaging seemsunable <strong>to</strong> consistently distinguish neoplasticfixation or invasion of <strong>the</strong> prevertebral musculaturefrom benign reaction. because bothFig. 5-52-year-old man with pharyngealcancer.A, Axial Ti -weighted MR image (600/17 [TR/TEI; section thickness, 5 mm)shows large pharyngeal mass (m)obliterating retropharyngeal fat andmildly compressing prevertebralmuscle complex (arrowheads).B, Axial 12-weighted MR image(3500/85; section thickness, 5 mm)shows increased signal intensity inmuscle (arrows). On panendoscopy,fixation of mass was equivocal. Onopen neck exploration tumor was notfreely mobile, and intraoperative biopsyrevealed tumor invading prever.tebral muscle.AJR:170, May i998 1393

Loevner et al.processes can have similar imaging findings.Abnormal 12 signal intensity or enhancementshould not be taken as an absolute mdicationof fixation or invasion because it maybe seen in patients whose tumors are resectable,as in this study. Currently, determiningfixation or invasion of primary head and neckcarcinomas <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> prevertebral compartmentmust be made intraoperatively. The numberof patients in our study was small (n = 15),and a study with a larger sample size isneeded for fur<strong>the</strong>r evaluation of this observation.O<strong>the</strong>r limitations include an imperfectgold standard for determining prevertebralmuscle invasion-namely, lack of pathologicproof of tumors determined <strong>to</strong> be fixed onpanendoscopy. The possibility of microscopicinvasion in patients with intact retropharyngeal-precervicalfat planes was alsonot addressed in this study.ReferencesI . Freeman DE, Mancuso AA, Parsons iT, MendenhallWM, Million RR. Irradiation alone for supraglotticlarynx carcinoma: can CT findings predicttreatment results? tnt J Radiat Oncol Biol Pin’s1990;l9:485-4902. Sanghvi V. The new combined surgical approachfor cancer involving <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>to</strong>ngue-supraglotticcomplex. Lar’ngoscope 1994;l04:725-7303. Loveday EJ, Bleach NR, Van Hasselt CA, MetreweliC. Ultrasound imaging in laryngeal cancer:a preliminary study. Clin Radio! 1994;49:676-6824. Zeitels SM, Vaughn CW. Preepiglottic space invasionin “early” epiglottic cancer. Ann O<strong>to</strong>! Rhino!Laryngo! 1991:100:789-7925. Ali YA, Saleh EM, Mancuso AA. Does conventional<strong>to</strong>mography still have a place in glotticcancer evaluation? C/in Radio! 1992;45: I 14-I 196. Mafee MF, Schild JA, Valva.ssori GE, Capek V.Computed <strong>to</strong>mography of <strong>the</strong> larynx: correlationwith ana<strong>to</strong>mic and pathologic studies in cases of Iaryngealcarcinoma. Radiology 1983;147: 123-1287. Hoover LA, Calcaterra IC, Walter GA, Larrson5G. Pre-operative CT scan evaluation for laryngealcarcinoma: correlation with pathologic findings.Lars’ngoscope 1984;94:3l0-3158. Gregory RT, Lloyd GAS, Michaels L. Computed<strong>to</strong>mography of <strong>the</strong> larynx: a clinical and pathologicstudy. Head Neck Surg 1981;3:284-2969. Tien RD, Hesselink JR. Chu PK, Szumowski J.Improved detection and delineation of head andneck lesions with fat-suppression spin-echo MRimaging. AJNR 1991:12:19-2410. van den Brekel MWM, Stel HV, Castelijns JA, etal. Cervical lymph node metastasis: assessment ofradiologic criteria. Radio!ogv 1990:177:379-384I I . Castelijns JA, Gemtsen GJ, Kaiser MC, et al. Invasionof laryngeal cartilage by cancer: comparisonof CT and MR imaging. Radio!ogv 1987:166:199-20612. Yousem DM, Som PM, Hackney DB, SchwaiboldF, Hendrix RA. Central nodal necrosis and extracapsularneoplastic spread in cervical lymphnodes: MR imaging versus CT. Radiology 1992;182:753-75913. Righi PD, Kelley DJ, Ernst R, Ct al. Evaluation ofprevertebral muscle invasion by squamous cellcarcinoma. Arch O<strong>to</strong>!arvngo! Head Neck Surg1996:122:660-66314. Madison MT. Remley KB, Latchaw RE, MitchellSL. Radiologic diagnosis and staging of head andneck squamous cell carcinoma. Radio! C!in NorthA,n 1994:32:163-18115. Parker GD. Harnsberger HR. Radiologic evaluationof <strong>the</strong> normal and disea.sed posterior cervicalspace.AJR1991;157:l6l-l6516. Davis WL, Hamsberger HR. Smoker WR. et al.Retropharyngeal space: evaluation of normalana<strong>to</strong>my and diseases with CT and MR imaging.Radiology 1990:174:59-6417. Paonessa DF. Goldstein JC. Ana<strong>to</strong>my and physiologyof head and neck infections (with emphasison <strong>the</strong> fascia of <strong>the</strong> face and neck). O<strong>to</strong>!arvngolC!in North Am 1976:9:561-580I 8. Som PM. Lymph nodes of <strong>the</strong> neck. Radiology1987; 165:593-60019. Dooms GC. Hncak H, Crooks LE. et al. Magneticresonance imaging of <strong>the</strong> lymph nodes: comparisonwith CT. Radiology 1984:153:719-72420. Muraki AJ, Mancuso AA, Harnsberger HR. Metastaticcervical adenopathy from tumors of unknownorigin: role of CT. Radiology 1984:152:749-75321. Dooms GC. Hricak H. Radiologic imaging modalities.including magnetic resonance, for evaluatinglymph nodes. West J Med 1986:144:49-5722. Becker M, Zbaren P. Laeng H. S<strong>to</strong>upis C. PorcelliniB, Vock P. <strong>Neoplastic</strong> invasion of <strong>the</strong> laryngealcartilage: comparison of MR imaging andCT with his<strong>to</strong>pathologic correlation. Radiology1995; 194:66 1-66923. Seeger LL, Widoff BE, Bassett LW, Rosen G,Eckardt ii. Preoperative evaluation of osteosarcoma:value of gadopentetate dimeglumine-enhancedMR imaging. AiR 1991:157:347-35124. Lang P. Honda G, Roberts 1, et al. Musculoskeletalneoplasm: perineoplastic edema versus tumoron dynamic postcontrast MR images with spatialmapping of instantaneous enhancement rates. Radio!ogv1995:197:831-8391394 AJR:170, May 1998