Reducing Ethnic Profiling in the European Union - Open Society ...

Reducing Ethnic Profiling in the European Union - Open Society ...

Reducing Ethnic Profiling in the European Union - Open Society ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

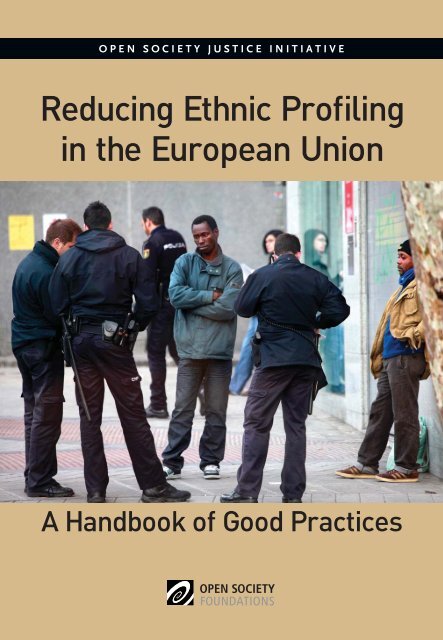

OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE<strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>A Handbook of Good Practices

<strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>:A Handbook of Good Practices

described <strong>in</strong> this report. The case studies presented here are not <strong>in</strong>tended as a currenthistorical record, but ra<strong>the</strong>r as a compilation of good practice that may serve as anexample of positive approaches that can be drawn on from one sett<strong>in</strong>g to ano<strong>the</strong>r.The <strong>Open</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Justice Initiative bears sole responsibility for any errors ormisrepresentation.4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Table of ContentsList of Case Studies 7Introduction 13I. <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Def<strong>in</strong>ed 17II. A Holistic Approach to <strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 29III. Legal Standards and Institutional Policies to Address <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 33IV. Oversight Bodies and Compla<strong>in</strong>ts Mechanisms 55V. <strong>Ethnic</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Law Enforcement Data-Ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g 75VI.Strategies for <strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> Disproportionality and Improv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> Quality of Encounters 103VII. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 125VIII. Chang<strong>in</strong>g Institutional Culture 135IX. Community Outreach and Involvement 147Appendix A: Sample Stop Forms 171Appendix B: Legal Standards and Case Law 191Appendix C: Bibliography of Key Texts 199Notes 2055

List of Case StudiesThe case studies marked with * have previously appeared <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Fundamental RightsAgency (FRA) publication, “Towards More Effective Polic<strong>in</strong>g; Understand<strong>in</strong>g and Prevent<strong>in</strong>gDiscrim<strong>in</strong>atory <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: A Guide,” Vienna: FRA, 2010. Several of <strong>the</strong>shared case studies that appear <strong>in</strong> this handbook have been updated.UNITED KINGDOM The Equality Act 2010NORTHERN IRELANDFRANCENORTHERN IRELANDAUSTRIAUNITED KINGDOMBELGIUMUNITED KINGDOMNETHERLANDSFRANCEStatutory Duty with Exemptions <strong>in</strong>Non-Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation LegislationObligation of Non-Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>National Police Code of ConductPolice Code of EthicsLegal Guidel<strong>in</strong>es on Non-Discrim<strong>in</strong>atoryConductPACE 1984 and O<strong>the</strong>r Stop and SearchLegislation *Brussels Airport Information-basedBehavioral <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Customs Guidel<strong>in</strong>es on Selection andSearches of PersonsPractical Guidance on Non-Discrim<strong>in</strong>atoryTreatment <strong>in</strong> Border ControlsPolice Stop Powers for Immigration ControlPurposes7

IRELANDNational Action Plan Aga<strong>in</strong>st RacismIRELAND Polic<strong>in</strong>g Plan 2008GREECEUNITED KINGDOMBELGIUMFRANCEIRELANDNORTHERN IRELANDNETHERLANDSUNITED KINGDOM/NORTHERN IRELANDUNITED KINGDOMDENMARKUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOM/NORTHERN IRELANDUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMRequirement to Investigate Racist IntentIndependent Police Compla<strong>in</strong>ts CommissionComité PNational Commission on Police EthicsGarda Síochana Ombudsman CommissionOffice of <strong>the</strong> Police OmbudsmanNational OmbudsmanNor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland Human RightsCommission’s Research: Our Hidden Borders:The UK Border Agency Power of DetentionEqualities and Human Rights CommissionInvestigation: Stop and Th<strong>in</strong>k!The Danish Institute of Human Rights Research<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Denmark—Legal Safeguardswith<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Field of <strong>the</strong> Work of <strong>the</strong> PoliceThe London Metropolitan Police AuthorityScrut<strong>in</strong>y Panel on Stop and SearchPolic<strong>in</strong>g Board Thematic Investigation <strong>in</strong>toChildren and Young PeopleThe Communities and Local GovernmentCommittee Review of <strong>the</strong> Prevent ProgramMerseyside Police Review of Stop DataUNITED KINGDOM West Yorkshire Police Use of BlackBerrys ®to Record Stop DataHUNGARY AND SPAINNETHERLANDSUNITED KINGDOMBELGIUM/GERMANY/ITALYRUSSIAFRANCE<strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> through <strong>the</strong>Introduction of Stop FormsStudy of Preventive Stop PowersSection 95 Data<strong>European</strong> Network Aga<strong>in</strong>st RacismSupplemental Reports on <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Moscow Metro<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Paris8 LIST OF CASE STUDIES

UNITED KINGDOMAUSTRIA/BELGIUM/BULGARIA/ITALY/ ROMANIA/SLOVAKIAIRELANDUNITED STATESUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMBULGARIA/HUNGARY/SPAINBELGIUMNORTHERN IRELANDIRELANDDENMARKSWEDENUNITED STATESBELGIUMUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMSPAINUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOM<strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Populations “Available” for Stopand SearchFRA Survey on M<strong>in</strong>orities’ Experience of LawEnforcementAttitud<strong>in</strong>al Survey of Traveller and <strong>Ethnic</strong>M<strong>in</strong>ority CommunitiesAttitud<strong>in</strong>al Survey of Young New YorkersPolice Stops and “Reasonable Suspicion”The Views of <strong>the</strong> Public on Stops andSearchesViews of <strong>the</strong> Police and Public on Stopsand SearchesRoundtables on Community Polic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Diverse NeighborhoodsBeyond <strong>the</strong> Marg<strong>in</strong>s: Build<strong>in</strong>g Trust <strong>in</strong>Polic<strong>in</strong>g with Young PeopleS<strong>in</strong>gled Out: Exploratory Study on <strong>Ethnic</strong><strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Ireland and its Impact on MigrantWorkers and <strong>the</strong>ir FamiliesMedia Report<strong>in</strong>g of Police Stop and SearchOperationsSwedish Brunch Report Radio ShowEnd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> EnhancesEffectivenessJudicial Control of <strong>the</strong> Use of SpecialInvestigative TechniquesNational Intelligence ModelBorder Agency Harm Scor<strong>in</strong>g MatrixUs<strong>in</strong>g Stop Data <strong>in</strong> Supervision andManagementComputerized Monitor<strong>in</strong>g of IndividualOfficers’ Stops <strong>in</strong> Hertfordshire *London Metropolitan Police Service’sOperation Pennant to Monitor Area Based<strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> *REDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 9

UNITED KINGDOM “Know Your Rights” Leaflets *UNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMHUNGARYAUSTRIAFRANCEUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOM“Go Wisely: Everyth<strong>in</strong>g you need to knowabout stop and search” DVD *“Know Your Rights” Mobile ApplicationCivilian Monitor<strong>in</strong>g through PoliceRide-AlongsAirport Monitor<strong>in</strong>g of Asylum ProceduresMonitor<strong>in</strong>g Treatment of Persons Await<strong>in</strong>gDeportation at AirportsInform<strong>in</strong>g Persons of <strong>the</strong> Reason for a Stopand SearchMonitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Quality of Encounters by <strong>the</strong>Hertfordshire Constabulary *AUSTRIA Courteous Forms of Address *GREECEProhibition of Racist LanguageIRELAND/NORTHERN IRELAND Diversity Works Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g *NETHERLANDSLeadership Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gUNITED KINGDOM Youth-Police Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on Stop and Search *SWEDENUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMNETHERLANDSBELGIUMUNITED KINGDOMNORTHERN IRELANDSWEDENSWEDENNETHERLANDSPolice and Youth Shar<strong>in</strong>g ExperiencesOperation Nicole Counter-Terrorism Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gBehavioral Assessment Screen<strong>in</strong>g System(BASS) Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and Passenger AssessmentScreen<strong>in</strong>g System (PASS)Amsterdam’s Information House Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gon RadicalizationIn-House Expertise on IslamPractice Orientated Package and Next StepsCreat<strong>in</strong>g a More Balanced Police Service<strong>in</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn IrelandDiversity Recruitment ProjectsWell-Intended Diversity Promotion thatBackfired“Safe Climates” Initiatives10 LIST OF CASE STUDIES

UNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMNETHERLANDSIRELANDIRELANDNETHERLANDSBELGIUMUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMIRELANDUNITED KINGDOMBlack Police AssociationsMPS Association of Muslim PoliceRole of National Diversity Unit <strong>in</strong> aDecentralized Polic<strong>in</strong>g SystemGarda Racial and Intercultural UnitBray’s “Garda on <strong>the</strong> Beat”Community Polic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> AmsterdamBrussels NorthPolice ESOLLondon MPS Cultural and CommunitiesResource UnitLondon Metropolitan Police ServiceConsultation StructuresMuslim Safety ForumCommunity Stop and Search Scrut<strong>in</strong>yPanels: West Yorkshire Police and SuffolkConstabularyDubl<strong>in</strong> North Central Divisional Forum withNew CommunitiesStrathclyde Police’s Counter-TerrorismCommunity ConsultationUNITED KINGDOM National Accountability Board for Schedule 7of <strong>the</strong> Terrorism ActUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMSWEDENUNITED KINGDOMUNITED KINGDOMIRELANDUNITED KINGDOMManchester Airport Independent AdvisoryGroupManchester Airport Critical IncidentResponseSpecial Initiatives Work<strong>in</strong>g withHard-to-Reach GroupsStrathclyde Police’s Operation ReclaimFair Cop-Engag<strong>in</strong>g Young People throughSocial MediaImprov<strong>in</strong>g Police Relations with TravellersLondon Metropolitan Police Service MuslimContact UnitREDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 11

Introduction<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g by police <strong>in</strong> Europe is a widespread form of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation. By focus<strong>in</strong>gon appearance ra<strong>the</strong>r than behavior, police who engage <strong>in</strong> ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g violate basichuman rights norms. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g is also <strong>in</strong>efficient: it leads police to focus on racialand ethnic traits ra<strong>the</strong>r than genu<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicators of suspicion, and results <strong>in</strong> stopp<strong>in</strong>gand search<strong>in</strong>g large numbers of <strong>in</strong>nocent people. Fortunately, better alternatives exist—approaches to polic<strong>in</strong>g that are more fair and more effective. This handbook documentsthose approaches and provides guidance for police officers, o<strong>the</strong>r law enforcement officials,and policymakers <strong>in</strong> how to reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. The guidel<strong>in</strong>es and casestudies set forth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g pages are <strong>in</strong>tended to help cut down on discrim<strong>in</strong>ationand <strong>in</strong>crease police efficacy.<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong> practice of us<strong>in</strong>g ethnicity, race, national orig<strong>in</strong>, or religionas a basis for mak<strong>in</strong>g law enforcement decisions about persons believed to be <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al activity. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g can result from discrim<strong>in</strong>atory decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g by<strong>in</strong>dividual law enforcement officers, or from law enforcement policies and practices thathave a disproportionate impact on specific groups without any legitimate law enforcementpurpose. It is often <strong>the</strong> result of beliefs deeply-<strong>in</strong>gra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual law enforcementofficers and even whole <strong>in</strong>stitutions and <strong>the</strong> societies <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>y operate.While not a new phenomenon, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g has <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong><strong>Union</strong> <strong>in</strong> recent years because of two factors: (1) ris<strong>in</strong>g concern about illegal immigration<strong>in</strong>to and movement of undocumented migrants with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>, and(2) <strong>the</strong> threat posed by terrorism <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aftermath of September 11th terrorist attack<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States and <strong>the</strong> subsequent March 2003 terrorist bomb<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> Madridand July 2005 bomb<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> London. These trends are described <strong>in</strong> detail <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Open</strong><strong>Society</strong> Justice Initiative’s 2009 report <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>: Pervasive,Ineffective, and Discrim<strong>in</strong>atory.13

The United Nations, <strong>the</strong> Council of Europe, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Commission havehighlighted ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as a particular area of concern with respect to discrim<strong>in</strong>atorypolic<strong>in</strong>g practices. International human rights monitor<strong>in</strong>g bodies have likewisehighlighted ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as an area of concern.The first step <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is to admit its existence and recognizeits discrim<strong>in</strong>atory nature. The next step is decid<strong>in</strong>g what to do about it. The f<strong>in</strong>al stepis implement<strong>in</strong>g new policies and practices that reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g and replace itwith more reasoned and effective procedures. <strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong><strong>Union</strong> aims to assist <strong>in</strong> this process by offer<strong>in</strong>g diagnostic questions, provid<strong>in</strong>g ideasand models of proven good practice, and identify<strong>in</strong>g challenges and impediments toreform. It is <strong>the</strong> result of a thorough review of exist<strong>in</strong>g laws and relevant academicliterature, field test<strong>in</strong>g of specific reforms, and extensive <strong>in</strong>teractions with state authorities,law enforcement agencies, civil society organizations, and local ethnic m<strong>in</strong>oritycommunities across <strong>the</strong> EU.<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g is not an easy issue to resolve. Law enforcement agencies mayfeel that a focus on ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g unfairly s<strong>in</strong>gles <strong>the</strong>m out as racist. For ethnicm<strong>in</strong>ority persons and communities, discussions of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g highlight stereotypesabout m<strong>in</strong>orities and offend<strong>in</strong>g.But while discussions of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation and racism are never easy, reduc<strong>in</strong>g ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g can be a w<strong>in</strong>-w<strong>in</strong> proposition that benefits law enforcement agencies and<strong>the</strong> many communities <strong>the</strong>y serve. Both research and first-hand experience—exemplified<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case studies throughout this handbook—demonstrate that adopt<strong>in</strong>g goodpractices not only supports fairer polic<strong>in</strong>g but can also improve <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of lawenforcement.This handbook provides a wide-rang<strong>in</strong>g review of current efforts to reduce ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g and support non-discrim<strong>in</strong>atory law enforcement. Its numerous case studiesexam<strong>in</strong>e: non-discrim<strong>in</strong>atory standards established <strong>in</strong> legal <strong>in</strong>struments and operationalguidel<strong>in</strong>es, research and monitor<strong>in</strong>g methodologies, <strong>in</strong>stitutional practices that createnon-discrim<strong>in</strong>atory workplaces that reflect <strong>the</strong> societies <strong>the</strong>y serve, and models of communityoutreach and engagement. The case studies and explanatory text aim to provideclear and practical support to all those seek<strong>in</strong>g to understand <strong>the</strong> dynamics and reduce<strong>the</strong> frequency of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. Taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y offer a holistic approach to lawenforcement that does not discrim<strong>in</strong>ate.Beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g with a def<strong>in</strong>ition of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, this handbook exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> needfor a holistic approach to reduc<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>n looks at <strong>the</strong> legal standards and<strong>in</strong>stitutional policies for address<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, as well as <strong>the</strong> oversight bodies andcompla<strong>in</strong>ts mechanisms relevant to <strong>the</strong> issue. Subsequent chapters explore <strong>the</strong> use ofethnicity <strong>in</strong> data ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g by law enforcement, strategies for reduc<strong>in</strong>g disproportionalityand improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> quality of contacts between police and community members, and14 INTRODUCTION

<strong>the</strong> importance of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, reform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutional cultures, and community outreach<strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. The book concludes with annexes document<strong>in</strong>g relevantlegal standards and case law and provid<strong>in</strong>g references for additional research.This handbook <strong>in</strong>cludes nearly 100 brief case studies drawn from 19 <strong>European</strong>countries and <strong>the</strong> United States. They are <strong>in</strong>tended as models for reform efforts,although it is important to bear <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d that any <strong>in</strong>itiative to reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>gmust be tailored to local circumstances. Each case study is <strong>in</strong>troduced with brief textexpla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g its significance, and each section closes with bullet po<strong>in</strong>ts summariz<strong>in</strong>g keyelements of <strong>the</strong> good practices represented <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case studies.The handbook has been prepared to support national and local authorities andlaw enforcement agencies across <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> as <strong>the</strong>y take steps to monitorand reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. It is <strong>in</strong>tended to help political authorities, oversight <strong>in</strong>stitutions,law enforcement entities, civil society organizations, and community representativesbetter understand <strong>the</strong> dynamics and costs of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, and aid <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g new partnerships, policies, and practices to address <strong>the</strong> problem. While thishandbook focuses on <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> legal standards and law enforcement practices,it has broader relevance for any sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> which ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g has been identified asan issue to be addressed.The practices and policies set out <strong>in</strong> this handbook are not mutually exclusive,but ra<strong>the</strong>r are meant to complement each o<strong>the</strong>r and add up to a holistic approach toreduc<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. In most sett<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>the</strong> best approach will be identified throughengagement and dialogue with <strong>the</strong> diverse communities that are affected by ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g: ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority groups, law enforcement <strong>in</strong>stitutions and officers, and legaland political authorities.Encourag<strong>in</strong>gly, <strong>the</strong> experiences ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>in</strong> this handbook demonstrate that <strong>the</strong>reis <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g recognition of <strong>the</strong> challenges of enforc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> law <strong>in</strong> racially and ethnicallydiverse communities, and of <strong>the</strong> need to <strong>in</strong>corporate non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesdirectly and explicitly <strong>in</strong>to law enforcement policy and practice. Efforts to address ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g can not only reduce discrim<strong>in</strong>atory practices and outcomes, but can alsoenhance <strong>the</strong> overall quality and efficiency of law enforcement.REDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 15

I. <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Def<strong>in</strong>edA Comprehensive Def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong> use by police of generalizations based on race, ethnicity, religionor national orig<strong>in</strong>—ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>in</strong>dividual behavior or objective evidence—as <strong>the</strong> basisfor law enforcement actions. 1 <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g underm<strong>in</strong>es a basic precept of <strong>the</strong> rule oflaw: that all persons deserve equal treatment under <strong>the</strong> law and that <strong>in</strong>dividual behaviorshould be <strong>the</strong> basis of legal liability. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g targets certa<strong>in</strong> persons because ofwhat <strong>the</strong>y look like and not what <strong>the</strong>y have done.<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g should not be confused with “crim<strong>in</strong>al profil<strong>in</strong>g,” which relieson statistical categorizations thought to correlate with specific behaviors, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> development of profiles for serial killers, hijackers, and drug couriers. Nor shouldethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g be conflated with <strong>in</strong>dividual “suspect profiles” or suspect descriptions,generally based on a witness description of a specific person connected with a particularcrime committed at a specific time and place. 2 If a robbery victim reports that herassailant was a tall blond man, it is reasonable for police to stop tall blond men <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>area, based on this suspect description. However, if a police officer stops every Romaperson he sees because of his personal conviction that Roma are likely to commit crime,this is ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g.As <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> example above, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g frequently results from decisions by<strong>in</strong>dividual officers. Some of <strong>the</strong>se officers may be explicitly racist, while o<strong>the</strong>rs may beunaware of <strong>the</strong> degree to which generalizations and ethnic stereotypes drive <strong>the</strong>ir subjectivedecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g about which <strong>in</strong>dividuals to subject to law enforcement action.While racist <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> law-enforcement <strong>in</strong>stitutions certa<strong>in</strong>ly contribute to ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g, 3 ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g rema<strong>in</strong>s persistent and pervasive precisely because it is <strong>the</strong>17

esult of a habitual, and often subconscious, use of widely-accepted negative stereotypes<strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g decisions about who appears suspicious. 4<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g may also result from <strong>in</strong>stitutional policies target<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> formsof crime and/or certa<strong>in</strong> geographic areas without consideration of <strong>the</strong> disproportionateimpact such policies and resource allocation have on m<strong>in</strong>ority communities. Policydecisions of this sort often reflect larger public and political concerns and, <strong>in</strong> somecases, public prejudices. However, <strong>the</strong>y can also arise from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture oflaw enforcement organizations as a whole, which build up a tradition of polic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>certa<strong>in</strong> ways, especially <strong>in</strong> relation to particular localities or groups with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir areas.This handbook def<strong>in</strong>es ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as encompass<strong>in</strong>g situations where ethnicity,race, national orig<strong>in</strong>, or religion is a significant—even if not <strong>the</strong> exclusive—basisfor mak<strong>in</strong>g law enforcement decisions. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g can also <strong>in</strong>clude situationswhere law enforcement policies and practices—although not def<strong>in</strong>ed by reference toethnicity, race, national orig<strong>in</strong>, or religion—never<strong>the</strong>less have a disproportionate impacton specific groups and where this disproportionate impact cannot be justified <strong>in</strong> termsof legitimate law enforcement objectives. In <strong>European</strong> law, <strong>the</strong> fact that discrim<strong>in</strong>atoryoutcomes may occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> absence of discrim<strong>in</strong>atory <strong>in</strong>tent is recognized <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> conceptof “<strong>in</strong>direct discrim<strong>in</strong>ation” established <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Racial Equality Directive(see fur<strong>the</strong>r discussion of legal standards below).British and American def<strong>in</strong>itions of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g recognize that it can be ei<strong>the</strong>rdeliberate or <strong>in</strong>direct. The 2003 guidance on racial profil<strong>in</strong>g issued by <strong>the</strong> United StatesDepartment of Justice states that:In mak<strong>in</strong>g rout<strong>in</strong>e or spontaneous law enforcement decisions, such as ord<strong>in</strong>ary traffic stops,Federal law enforcement officers may not use race or ethnicity to any degree, except thatofficers may rely on race and ethnicity <strong>in</strong> a specific suspect description. […] In conduct<strong>in</strong>gactivities <strong>in</strong> connection with a specific <strong>in</strong>vestigation, Federal law enforcement officers mayconsider race and ethnicity only to <strong>the</strong> extent that <strong>the</strong>re is trustworthy <strong>in</strong>formation, relevantto <strong>the</strong> locality or timeframe, that l<strong>in</strong>ks persons of a particular race or ethnicity to an identifiedcrim<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>cident, scheme, or organization. This standard applies even where <strong>the</strong> use of raceor ethnicity might o<strong>the</strong>rwise be lawful. 5In <strong>the</strong> United K<strong>in</strong>gdom, <strong>the</strong> 1984 Police and Crim<strong>in</strong>al Evidence Act (PACE)expressly addressed ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g by establish<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> reasonable suspicionbeh<strong>in</strong>d a stop and search “cannot be based on generalizations or stereotypical images ofcerta<strong>in</strong> groups or categories of people as more likely to be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al activity.” 6While <strong>European</strong> law has yet to codify a s<strong>in</strong>gle def<strong>in</strong>ition of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, severaldifferent def<strong>in</strong>itions have been proposed by <strong>European</strong> bodies and civil society actors.The Council of Europe’s <strong>European</strong> Commission aga<strong>in</strong>st Racism and Intolerance (ECRI)has def<strong>in</strong>ed ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as18 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

The use by <strong>the</strong> police, with no objective and reasonable justification, of grounds such as race,colour, language, religion, nationality or national or ethnic orig<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> control, surveillance or<strong>in</strong>vestigation activities. 7The <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights,<strong>in</strong> turn, has def<strong>in</strong>ed it as[T]he practice of us<strong>in</strong>g ‘race’ or ethnic orig<strong>in</strong>, religion, or national orig<strong>in</strong>, as ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> solefactor, or one of several factors <strong>in</strong> law enforcement decisions, on a systematic basis, whe<strong>the</strong>ror not concerned <strong>in</strong>dividuals are identified by automatic means. 8The <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) uses <strong>the</strong> term “discrim<strong>in</strong>atoryethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g” <strong>in</strong> its def<strong>in</strong>ition, stat<strong>in</strong>g that discrim<strong>in</strong>atory ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>volves “treat<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>dividual less favorably than o<strong>the</strong>rs who are <strong>in</strong> a similar situation(<strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r words, ‘discrim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g’), for example, by exercis<strong>in</strong>g police powers such as stopand search.” Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> FRA, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is present “[w]here a decision to exercisepolice powers is based only or ma<strong>in</strong>ly on that person’s race, ethnicity or religion.” 9The FRA’s approach reflects a conceptual and semantic confusion that cont<strong>in</strong>uesto dog <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>’s discussions of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. The use of <strong>the</strong> term “discrim<strong>in</strong>atoryethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g” implies that <strong>the</strong>re can be ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g that is not discrim<strong>in</strong>atory.But “ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g” refers specifically to a form of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> lawenforcement; to add <strong>the</strong> adjective “discrim<strong>in</strong>atory” to <strong>the</strong> term mislead<strong>in</strong>gly suggeststhat <strong>the</strong>re may be non-discrim<strong>in</strong>atory ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. This confusion reflects a conflationof “ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g,” which refers to discrim<strong>in</strong>atory practices or outcomes <strong>in</strong> lawenforcement, and “crim<strong>in</strong>al profil<strong>in</strong>g,” which describes an <strong>in</strong>vestigative technique thatrelies on statistical <strong>in</strong>ferences to detect persons <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> crime and which may or maynot <strong>in</strong>clude sensitive personal data such as race, ethnicity, religion, or national orig<strong>in</strong>.Fur<strong>the</strong>r def<strong>in</strong>itional confusion arises from efforts by <strong>the</strong> Council of Europe and<strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> to update personal data protection standards <strong>in</strong> response to new datam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g techniques enabled by rapid technological advances. A 2010 recommendationof <strong>the</strong> Council of Europe def<strong>in</strong>es profil<strong>in</strong>g as: “an automatic data process<strong>in</strong>g techniquethat consists of apply<strong>in</strong>g a ‘profile’ to an <strong>in</strong>dividual, particularly <strong>in</strong> order to take decisionsconcern<strong>in</strong>g her or him or for analys<strong>in</strong>g or predict<strong>in</strong>g her or his personal preferences,behaviours and attitudes.” 10 <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g may constitute a subset of profil<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. However, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> law enforcement activity <strong>in</strong> questionis an identity check on <strong>the</strong> street or an algorithm-based search of databases, when<strong>the</strong>se actions use ethnicity, religion, or race (or proxies for <strong>the</strong>m) ra<strong>the</strong>r than suspiciousbehavior, <strong>the</strong>y constitute ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g and are an unlawful form of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation.Law enforcement’s use of data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to conduct ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is of particularREDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 19

concern <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of counter-terrorism, as law enforcement agencies have developeda new <strong>in</strong>terest on <strong>the</strong> potential of data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g as a counter-terrorism tool.The Council of Europe’s def<strong>in</strong>ition of data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g seeks to position profil<strong>in</strong>g asa neutral process of <strong>in</strong>vestigation, and ignores <strong>the</strong> risks of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong>generaliz<strong>in</strong>g about whole groups of people. It fails to establish ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as aspecific term referr<strong>in</strong>g to a discrim<strong>in</strong>atory law enforcement practice.Data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r forms of crim<strong>in</strong>al profil<strong>in</strong>g may cull personal data andat times sensitive personal data on ethnicity, religion, national orig<strong>in</strong>, and o<strong>the</strong>r elementsfor <strong>in</strong>vestigative purposes. Where <strong>the</strong>re is a basis <strong>in</strong> specific and timely <strong>in</strong>telligence,such as a victim or witness description or reliable and timely <strong>in</strong>telligence that<strong>in</strong>cludes ethnic appearance or national orig<strong>in</strong>, such use of sensitive personal data maybe necessary and proportional and would not constitute ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. But when <strong>the</strong>use of sensitive personal data reflects stereotypes or generalizations that connect basicpersonal characteristics (such as be<strong>in</strong>g a Muslim, from certa<strong>in</strong> countries, male andbetween <strong>the</strong> age of 16 and 30) with a propensity to offend, it crosses <strong>the</strong> boundary <strong>in</strong>toethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g.Strategies to prevent terrorism can also raise concerns about ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g.One counter-terrorism tactic that merits particular mention is “counter-radicalization”or <strong>the</strong> attempt to identify <strong>in</strong>dividuals thought to be at risk of sympathiz<strong>in</strong>g with orturn<strong>in</strong>g toward terrorism. In seek<strong>in</strong>g to identify persons <strong>in</strong> early stages of sympathy forterrorism, some counter-radicalization approaches focus on beliefs ra<strong>the</strong>r than actions.Counter-radicalization strategies often rest on broad generalizations about religiouspractice, with police and <strong>in</strong>telligence services target<strong>in</strong>g practitioners of certa<strong>in</strong>tenets of Islam (such as Salafism or Wahhabism) even without concrete evidence of<strong>the</strong> practitioners’ <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> terrorist activities. In this approach, <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctionbetween an orthodox or “fundamentalist” practice of Islam and will<strong>in</strong>gness to participate<strong>in</strong> terrorist acts can be blurred. Followers of certa<strong>in</strong> forms of Islam have beenlabeled as “radical”—even if <strong>the</strong>y do not promote violence—based on <strong>the</strong> nature of<strong>the</strong>ir religious belief. These assumptions have been criticized <strong>in</strong> numerous studies thatf<strong>in</strong>d no consistent path to radicalization 11 and no connection between Muslim religiousviews and political radicalization. 12 In fact, a study by <strong>the</strong> British <strong>in</strong>telligence servicesnoted that adherence to non-violent orthodox or “fundamentalist” streams of Islam maymilitate aga<strong>in</strong>st violent radicalization and that such groups can be important allies <strong>in</strong>“de-radicalization.” 13Immigration enforcement is ano<strong>the</strong>r law enforcement context <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> useof physical appearance, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g ethnicity, is common—<strong>in</strong> this case, to determ<strong>in</strong>ewho may be an undocumented foreigner. In August 2010, <strong>the</strong> French M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>the</strong>Interior issued an <strong>in</strong>ternal circular task<strong>in</strong>g police to round-up persons who appeared tobe Roma immigrants and deport <strong>the</strong>m to Romania. 14 The target<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>dividuals based20 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

explicitly on <strong>the</strong>ir membership <strong>in</strong> a m<strong>in</strong>ority group constitutes illegal discrim<strong>in</strong>ation. 15O<strong>the</strong>r immigration enforcement practices, such as giv<strong>in</strong>g police quotas of how manyundocumented migrants to identify and deta<strong>in</strong> for deportation, have not garnered asmuch <strong>in</strong>ternational attention as <strong>the</strong> expulsions of Roma, but clearly drive <strong>the</strong> use ofhighly discrim<strong>in</strong>atory mass identity checks and raids target<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>ority neighborhoods.In an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly multi-ethnic Europe, us<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g to control immigrationimposes an undue burden on m<strong>in</strong>ority citizens: law enforcement cont<strong>in</strong>ues touse ethnicity as a proxy for immigration status even when those be<strong>in</strong>g targeted wereborn <strong>in</strong> <strong>European</strong> countries or have been legally resident <strong>the</strong>re for years. This creates adual standard <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> enjoyment of basic citizenship rights that violates <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple ofequal treatment: those who “look <strong>European</strong>” do not get stopped and asked for identitypapers, while those who “look like foreigners” bear <strong>the</strong> burden of disproportionatepolice attention. 16In practice, it is best to apply a strict standard and avoid <strong>the</strong> use of sensitive personalfactors such as ethnicity, religion, and national orig<strong>in</strong> except <strong>in</strong> those cases whereit is part of a reliable <strong>in</strong>dividual suspect description. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> EU Network onIndependent Experts on Fundamental Rights:[T]he consequences of treat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals similarly situated differently accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>irsupposed ‘race’ or to <strong>the</strong>ir ethnicity has so far-reach<strong>in</strong>g consequences <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g divisivenessand resentment, <strong>in</strong> feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to stereotypes, and <strong>in</strong> lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> over-crim<strong>in</strong>alization ofcerta<strong>in</strong> categories of person <strong>in</strong> turn re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g such stereotypical associations between crimeand ethnicity, that differential treatment on this ground should <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple be consideredunlawful under any circumstance. 17To summarize, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g:• Is a form of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation;• Refers specifically to law enforcement practices, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those of <strong>the</strong> police,<strong>in</strong>telligence officials, border guards, immigration and customs authorities;• Is not limited to <strong>the</strong> explicit or sole use of ethnicity;• Can result from explicit target<strong>in</strong>g of m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> law enforcement actionssuch as stop and search and immigration enforcement;• Can result from racist acts of <strong>in</strong>dividuals law enforcement officers, but is mostcommonly <strong>the</strong> result of reliance on widely-held stereotypes about <strong>the</strong> relationshipbetween crime and ethnicity;• Can result from management and operational decisions which target specificcrimes or specific neighborhoods without consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> potentially disproportionateimpact of <strong>the</strong>se strategies on ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities.REDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 21

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as a Prohibited Form of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g is clearly prohibited under <strong>European</strong> and <strong>in</strong>ternational law.Both <strong>the</strong> United Nations Committee on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of Racial Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation(CERD) and <strong>the</strong> Council of Europe <strong>European</strong> Commission aga<strong>in</strong>st Racism and Intolerance(ECRI) have made clear that ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g violates <strong>the</strong> prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>stdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation. In 1994, CERD raised a concern regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need “to ensure thatpreventive identity checks were not be<strong>in</strong>g carried out <strong>in</strong> a discrim<strong>in</strong>atory manner by<strong>the</strong> police.” 18 ECRI’s General Policy Recommendation No. 11 def<strong>in</strong>es ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>gand calls on states to “ensure that legislation prohibit<strong>in</strong>g direct and <strong>in</strong>direct racial discrim<strong>in</strong>ationcover <strong>the</strong> activities of <strong>the</strong> police.” 19 The FRA has likewise noted that “[a]nyform of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is likely to be illegal also <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>in</strong>ternational law becauseit <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>ges <strong>the</strong> guarantees of <strong>the</strong> International Convention on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of allForms of Racial Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation,” to which all EU member states are bound. 20These declarations are consistent with <strong>European</strong> and <strong>in</strong>ternational jurisprudence<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> prohibitions aga<strong>in</strong>st racial discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Article 1 of InternationalConvention on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of Racism and Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation (ICERD) 21 and Article 14of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Convention on Human Rights. 22Under <strong>the</strong> govern<strong>in</strong>g case law of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Court of Human Rights (ECtHR),<strong>the</strong> test for discrim<strong>in</strong>ation is two-fold: (i) whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re has been a difference of treatmentsuch that persons of ano<strong>the</strong>r ethnic, racial, or religious group <strong>in</strong> “relevantly similar”situations are treated differently; and (ii) whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> difference <strong>in</strong> treatment has anobjective and reasonable justification when “assessed <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>the</strong> aim and effects”of <strong>the</strong> measure at issue. 23 In its lead<strong>in</strong>g judgment on this topic, <strong>the</strong> ECtHR found abreach of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Convention on Human Rights where Russian police officers,act<strong>in</strong>g pursuant to an official policy of ethnic exclusion, barred a man from cross<strong>in</strong>gan <strong>in</strong>ternal adm<strong>in</strong>istrative boundary because of his Chechen ethnicity. The court heldthat “no difference <strong>in</strong> treatment which was based exclusively or to a decisive extent on aperson’s ethnic orig<strong>in</strong> was capable of be<strong>in</strong>g objectively justified <strong>in</strong> a contemporary democraticsociety built on <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of pluralism and respect for different cultures.” 24In June 2009, <strong>the</strong> United Nations Human Rights Committee ruled <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> caseof Rosal<strong>in</strong>d Williams Lecraft v. Spa<strong>in</strong>, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that she had been s<strong>in</strong>gled out by Spanishpolice for an identity check solely on <strong>the</strong> ground of her racial characteristics and that,<strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se characteristics <strong>the</strong> decisive factor <strong>in</strong> her be<strong>in</strong>g suspected of unlawfulconduct, Spa<strong>in</strong> was <strong>in</strong> violation of <strong>the</strong> International Covenant on Civil and PoliticalRights. 25 The committee ruled that immigration checks should not be carried out <strong>in</strong>such a way as to target only persons with specific physical or ethnic characteristics, andthat while <strong>the</strong> conduct of identity checks <strong>in</strong> immigration control serves a legitimate purpose,“when <strong>the</strong> authorities carry out such checks, <strong>the</strong> physical or ethnic characteristics22 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

of <strong>the</strong> persons subjected <strong>the</strong>reto should not by <strong>the</strong>mselves be deemed <strong>in</strong>dicative of <strong>the</strong>irpossible illegal presence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country.” 26The ECtHR has made clear that a difference <strong>in</strong> treatment must not only pursuea legitimate aim—it must also obey a reasonable relationship of proportionalitybetween <strong>the</strong> means employed and <strong>the</strong> aim sought to be realized. 27 <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>gby law enforcement officers is unlawful unless it meets <strong>the</strong>se criteria establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>validity of differential treatment.The ECtHR has ruled that police powers of stop and search must be clear, usedaccountably, and respect privacy rights. In <strong>the</strong> landmark Gillan and Qu<strong>in</strong>ton v. <strong>the</strong> UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom case, <strong>the</strong> court found that <strong>the</strong> British law which granted police broad powers tostop and search persons without any requirement of reasonable suspicion was unlawful.The court’s January 2010 decision noted that “<strong>the</strong> powers of authorisation and confirmationas well as those of stop and search under sections 44 and 45 of <strong>the</strong> 2000 [UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom Prevention of Terrorism] Act are nei<strong>the</strong>r sufficiently circumscribed nor subjectto adequate legal safeguards aga<strong>in</strong>st abuse. They are not, <strong>the</strong>refore, ‘<strong>in</strong> accordancewith <strong>the</strong> law’.” 28 The court noted <strong>the</strong> clear risk of arbitrar<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> grant of such abroad discretion to <strong>the</strong> police officer, 29 as well as <strong>the</strong> risks of discrim<strong>in</strong>atory use of suchpowers, given statistics show<strong>in</strong>g that black and Asian persons are disproportionatelyaffected by <strong>the</strong> powers. 30In <strong>the</strong> realm of border control, <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Commission’s Practical Handbookfor Border Guards (Schengen Handbook) enshr<strong>in</strong>es non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation pr<strong>in</strong>ciples asfollows:Fundamental Rights enshr<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Convention on Human Rights and <strong>the</strong> Charterof Fundamental Rights of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> must be guaranteed to any person seek<strong>in</strong>gto cross borders. Border control must notably fully comply with <strong>the</strong> prohibition on <strong>in</strong>humanand degrad<strong>in</strong>g treatments and <strong>the</strong> prohibition of discrim<strong>in</strong>ation enshr<strong>in</strong>ed, respectively, <strong>in</strong>Articles 3 and 14 of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Convention on Human Rights and <strong>in</strong> Articles 4 and 21 of<strong>the</strong> Charter of Fundamental Rights of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>.In particular, border guards must, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> performance of <strong>the</strong>ir duties, fully respect humandignity and must not discrim<strong>in</strong>ate aga<strong>in</strong>st persons on grounds of sex, racial or ethnic orig<strong>in</strong>,religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation. Any measures taken <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> performanceof <strong>the</strong>ir duties must be proportionate to <strong>the</strong> objectives pursued by such measures.All travelers have <strong>the</strong> right to be <strong>in</strong>formed of <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong> controls and to a professional,friendly and courteous treatment, <strong>in</strong> accordance with applicable <strong>in</strong>ternational, communityand national law. 31The United Nations Committee on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of Racial Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation(CERD) has emphasized that <strong>the</strong> prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st racial discrim<strong>in</strong>ation is a peremptoryand non-derogable norm, and that states must ensure that counter-terrorismREDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 23

programs do “not discrim<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> purpose or effect on grounds of race, colour, descentor national or ethnic orig<strong>in</strong> and that non-citizens are not subjected to racial or ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g or stereotyp<strong>in</strong>g.” 32 Similarly, ECRI’s General Policy Recommendation No. 8 oncombat<strong>in</strong>g racism while fight<strong>in</strong>g terrorism specifically recommends that governmentspay particular attention to ensur<strong>in</strong>g that no discrim<strong>in</strong>ation ensues from legislation andregulations—or <strong>the</strong>ir implementation—govern<strong>in</strong>g checks carried out by law enforcementofficials with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> countries and by border control personnel. 33The Impact of <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on Individuals,Communities, and Law Enforcement<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g, whe<strong>the</strong>r deliberate or un<strong>in</strong>tended, has direct and harmful consequencesfor <strong>in</strong>dividuals and communities. It also has a negative effect on <strong>the</strong> law enforcementagencies and agents that engage <strong>in</strong> it.The impact of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong>dividualsFor <strong>in</strong>dividual victims of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> experience has been described as “frighten<strong>in</strong>g,humiliat<strong>in</strong>g or even traumatic.” 34 Mental health professionals have l<strong>in</strong>ked it to“post-traumatic stress disorder and o<strong>the</strong>r forms of stress-related disorders, perceptionsof race-related threats, and failure to use available community resources.” 35<strong>Ethnic</strong> m<strong>in</strong>orities across Europe are clearly suffer<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> negative effects ofethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g. In Spa<strong>in</strong>, a young male immigrant told researchers “I worry when Igo on <strong>the</strong> street that <strong>the</strong>y will stop me and <strong>the</strong>y ask me for my papers, because of <strong>the</strong>color of my sk<strong>in</strong>, by my way of walk<strong>in</strong>g.” 36 Ano<strong>the</strong>r victim of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong>added that “<strong>the</strong> police always come and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> end <strong>the</strong> kid th<strong>in</strong>ks that he is guilty. Theyfeel bad, <strong>the</strong>y feel <strong>in</strong>secure, <strong>the</strong>y feel like crim<strong>in</strong>als and <strong>the</strong>y feel that <strong>the</strong>y are bad.” 37M<strong>in</strong>ority youth <strong>in</strong> France likewise experience police controls as arbitrary and publiclyhumiliat<strong>in</strong>g. They describe <strong>in</strong>teractions that often <strong>in</strong>volve rough treatment at <strong>the</strong>hands of <strong>the</strong> police, such as be<strong>in</strong>g pushed aga<strong>in</strong>st a wall or be<strong>in</strong>g made to lie on <strong>the</strong>ground. In <strong>the</strong>ir words, “[p]olice controls make life impossible for any foreigner <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>country without papers, or anyone who is too black, too Arab, too tan, too stereotype,too young, too poor.” 38Beyond feel<strong>in</strong>gs of persecution, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volves widespread violationsof important fundamental rights, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g freedom of movement, freedom ofreligion, <strong>the</strong> right to assembly, <strong>the</strong> right to privacy, and <strong>the</strong> right to non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation.These violations are manifested through wrongful searches, arrests, convictions, anddeportations.24 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

The impact of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g on communitiesThe assumption that an ethnic or national identity, or a religion, directly correlates withcrim<strong>in</strong>ality grossly stigmatizes entire groups of people. Such stigmatization has concreteeffects on m<strong>in</strong>ority communities: it perpetuates negative stereotypes, legitimizesracism, leaves members of those communities less likely to cooperate with police, andcontributes to <strong>the</strong> overrepresentation of ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system.University of Chicago Professor Bernard Harcourt has described a “ratchet effect,”<strong>in</strong> which disproportionate law enforcement attention on specific communities leads to<strong>in</strong>creased crim<strong>in</strong>al justice contacts and arrests among members of those communities.Those communities become over-represented <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system, feed<strong>in</strong>ga public perception of higher crim<strong>in</strong>ality among members of those communities, andthis perception leads to <strong>in</strong>creased law enforcement attention on <strong>the</strong> communities <strong>in</strong>question, complet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> vicious cycle. In <strong>the</strong> United States, <strong>the</strong> ratchet effect has contributedto belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> stereotype of “black crim<strong>in</strong>ality” among police officers and <strong>the</strong>general public, underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ability of African-Americans to obta<strong>in</strong> employment orpursue educational opportunities.<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g delegitimizes <strong>the</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes of thoseaffected, push<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m away from cooperation with law enforcement and perhapseven encourag<strong>in</strong>g disaffected youth to commit crime. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g can corrodepolice-community relations, hamper<strong>in</strong>g law enforcement efforts to combat crime byalienat<strong>in</strong>g whole segments of society. 39 The effect of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g can be seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong>, most clearly <strong>in</strong> studies of sentenc<strong>in</strong>g disparities and <strong>the</strong> over-representationof ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong> <strong>European</strong> prison populations. 40<strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g by police can reflect prejudices with<strong>in</strong> a society, but ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>gand its effects can also feed biases <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> broader society. Law enforcement’sstigmatization of particular communities as more likely to commit crimes contributesto stereotypes about ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority groups, signal<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> broader society that allmembers of that group constitute a threat. If <strong>the</strong> police, guided by prejudices, can act<strong>in</strong> a discrim<strong>in</strong>atory manner, why should <strong>the</strong> shop-keeper, restaurant owner, or airl<strong>in</strong>esteward not do likewise?Unchecked and widespread profil<strong>in</strong>g has also contributed directly to civil unrest,as was <strong>the</strong> case <strong>in</strong> 1981 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Brixton area of London and <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r British cities. TheBrixton riots <strong>in</strong> particular were described as “an outburst of anger and resentment byyoung black people aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> police” follow<strong>in</strong>g an aggressive police operation that<strong>in</strong>volved large-scale stops and searches of young, black men. 41 Similar dynamics wereat play <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> French riots of 2005, 42 which were triggered by <strong>the</strong> accidental death oftwo m<strong>in</strong>ority youths who were avoid<strong>in</strong>g a police identity check. In February 2008, <strong>the</strong>Nørrebro district of Copenhagen, Denmark erupted follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> alleged mistreatmentREDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 25

y Danish police of an elderly man of Palest<strong>in</strong>ian orig<strong>in</strong> who was try<strong>in</strong>g to prevent <strong>the</strong>police from stopp<strong>in</strong>g and search<strong>in</strong>g ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dividual. 43 Danish media reports andcivil society activists attributed <strong>the</strong> civil unrest to <strong>the</strong> rout<strong>in</strong>e use of stop-and-search <strong>in</strong>m<strong>in</strong>ority areas. 44Ano<strong>the</strong>r adverse effect of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong>creased levels of hostility <strong>in</strong> encountersbetween <strong>in</strong>dividuals and law enforcement officers. Greater hostility <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>the</strong>chances that rout<strong>in</strong>e encounters will escalate <strong>in</strong>toaggression and conflict, pos<strong>in</strong>g safety concernsHIT RATESfor officers and community members alike. 45The “hit rate” is <strong>the</strong> proportionThe impact of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g on law enforcementof identity checks or stops andsearches that result <strong>in</strong> formal <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g has a direct and deleterious effectlaw enforcement action, such on law enforcement. It reduces security because itas an arrest or summons for an does not work, it misdirects police resources, and<strong>in</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>gement.it alienates people whose cooperation is necessaryfor effective crime detection.DISPROPORTIONALITYWhen accused of engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g,law enforcement officials often respond“Disproportionality” <strong>in</strong> stopsrefers to <strong>the</strong> extent to which that <strong>the</strong>y are simply react<strong>in</strong>g to higher crime andstop powers are be<strong>in</strong>g used on offend<strong>in</strong>g rates <strong>in</strong> ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority communities,different ethnic or nationality and that by target<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se persons, places, andgroups <strong>in</strong> proportion to <strong>the</strong>ir offenses, <strong>the</strong>y are engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> “good polic<strong>in</strong>g.”prevalence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wider society. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong>y argue that ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>gOdds-ratios, which compare works.measure <strong>the</strong> odds of be<strong>in</strong>gIn practice, however, <strong>the</strong>re is little evidencestopped if you are an ethnic that profil<strong>in</strong>g is an effective approach to combat<strong>in</strong>grime. Studies f<strong>in</strong>d that stereotypes appear tom<strong>in</strong>ority and <strong>the</strong> odds ofbe<strong>in</strong>g stopped if you are a have greater <strong>in</strong>fluence than crime data <strong>in</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>gofficers’ discretionary decisions. In <strong>the</strong> UK,non-m<strong>in</strong>ority, are one way ofmeasur<strong>in</strong>g disproportionality. self-report surveys f<strong>in</strong>d that black and white peoplereport equal levels of drug use. Yet police dataOdds ratios under 1.5 <strong>in</strong>dicatean absence of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g; show that black people are stopped by police moreodds ratios between 1.5 and frequently than white people for drug offenses. 462.0 <strong>in</strong>dicate that a bias mightIn fact, when police treat an entire group ofexist; and odds-ratios above 2.0 people as suspicious, <strong>the</strong>y are more likely to miss<strong>in</strong>dicate that police are target<strong>in</strong>g dangerous persons who do not fit <strong>the</strong> profile.ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities for stops. <strong>Ethnic</strong> profil<strong>in</strong>g can be both over-<strong>in</strong>clusive andunder-<strong>in</strong>clusive. It is over-<strong>in</strong>clusive <strong>in</strong> that most26 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

of <strong>the</strong> ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities disproportionately targeted for law enforcement operations are<strong>in</strong>nocent of <strong>the</strong> suspected crime or <strong>in</strong>fraction. It is under-<strong>in</strong>clusive <strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong>re may becrim<strong>in</strong>als who do not fit <strong>the</strong> profile and can <strong>the</strong>refore escape attention.Research from <strong>the</strong> United K<strong>in</strong>gdom <strong>in</strong>dicates that where levels of police officerdiscretion are high—that is, where officers have greater freedom to stop whoever <strong>the</strong>ywant—generalizations and negative stereotypes about “likely” offenders play an importantrole <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> officers’ decisions. 47 However, when officers are required to justify orarticulate grounds for suspicion before stopp<strong>in</strong>g citizens, <strong>the</strong> officers become less likelyto use generalizations about race, ethnicity, or religion. Instead, <strong>the</strong> officers focus onbehavioral factors ra<strong>the</strong>r than appearance. This shift from not<strong>in</strong>g superficial appearanceto exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual behavior <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>the</strong> rate at which law enforcement stopsproduce positive results—known as a “hit rate.” 48Studies have confirmed that reliance on ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g reduces hit rates, underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>glaw enforcement efficiency. 49 A 2005 study of <strong>the</strong> efficiency of preventivesearches for weapons <strong>in</strong> eight Dutch cities found that <strong>the</strong> searches disproportionatelytargeted m<strong>in</strong>orities and that <strong>the</strong> hit rate was only 2.5 percent: for every 1,000 peoplesearched, only 25 weapons were detected. 50 Not only is this a low hit rate, but <strong>the</strong> cost<strong>in</strong> terms of police officer-hours was extremely high—54 operations <strong>in</strong> Amsterdam tooknearly 12,000 hours of police time; resource costs were similarly high for equally limitedresults <strong>in</strong> Rotterdam. 51Clearly, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g underm<strong>in</strong>es effective polic<strong>in</strong>g by misdirect<strong>in</strong>g scarce lawenforcement resources. But it also underm<strong>in</strong>es polic<strong>in</strong>g by alienat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals andwhole communities who might o<strong>the</strong>rwise be an asset to law enforcement. Polic<strong>in</strong>g isprofoundly dependent on <strong>the</strong> cooperation of <strong>the</strong> general public: law enforcement needs<strong>the</strong> public to report crimes and provide suspect descriptions and witness testimony.British and American research shows that unsatisfactory contacts with law enforcementcan have a negative impact on public confidence <strong>in</strong> law enforcement, not only for <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>dividual directly <strong>in</strong>volved, but also for his family, friends, and associates. 52 Researchalso demonstrates that mistreatment by law enforcement officers is associated withreduced public cooperation with <strong>the</strong> law enforcement. 53 And without <strong>the</strong> public’scooperation, law enforcement becomes much more difficult: A study <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom found that only 15 percent of crimes solved were attributable to <strong>the</strong> policeact<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong>ir own, 54 and <strong>the</strong> number of crimes solved us<strong>in</strong>g only forensic evidencewas under five percent. 55In addition to be<strong>in</strong>g discrim<strong>in</strong>atory, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong>effective, <strong>in</strong>efficient, andalienat<strong>in</strong>g. It causes direct harm to <strong>the</strong> people and communities who are profiled, andalso harms law enforcement by render<strong>in</strong>g it less effective. And it does <strong>in</strong>direct damageto society at large, which is left with re<strong>in</strong>forced stereotypes and less security as a resultof wasted police resources.REDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 27

However, as this handbook seeks to demonstrate, better alternatives to ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g exist. For example, <strong>the</strong>re is evidence that remov<strong>in</strong>g ethnicity from a crim<strong>in</strong>alprofile and oblig<strong>in</strong>g officers to focus on specified non-ethnic criteria can help avoid discrim<strong>in</strong>ationand improve efficiency. A 1998 <strong>in</strong>itiative undertaken by <strong>the</strong> United StatesCustoms Service showed that bas<strong>in</strong>g searches on behavioural <strong>in</strong>dicators and requir<strong>in</strong>gsupervisor authorization ended racial disparities, and more than doubled <strong>the</strong> hit rate(discussed <strong>in</strong> case study <strong>in</strong> Chapter 6). These and o<strong>the</strong>r examples explored <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>gchapters show that it is possible to reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g and replace it withmore efficient and effective—and less biased—practices.28 ETHNIC PROFILING DEFINED

II. A Holistic Approachto <strong>Reduc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Profil<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Given its negative effects on <strong>in</strong>dividuals, ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority communities, and law enforcementefficacy, ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g should be addressed, ameliorated, and ultimately eradicated.In order to do so, political leaders and senior law enforcement management mustfirst recognize that ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g may be a problem. The next step is to exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>specific dynamics that produce unjustified and disproportionate focus on ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities<strong>in</strong> law enforcement actions. F<strong>in</strong>ally, law enforcement agencies must <strong>in</strong>troduce andimplement new management and operational practices.Recognition of ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g as a problem often emerges <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aftermath ofcivic unrest and deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g relations between law enforcement and ethnic m<strong>in</strong>oritycommunities, as happened <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United K<strong>in</strong>gdom follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1981 Brixton riots.A commitment to study and address ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g can also follow <strong>the</strong> implementationof new anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation laws and <strong>the</strong> establishment of national equality policieswhich affect <strong>the</strong> work of law enforcement <strong>in</strong>stitutions. Law enforcement agencies<strong>the</strong>mselves can also choose to proactively reach out to ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority communities andadopt more equitable policies and practices. Proactive efforts can <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gethnic, racial, and religious diversity with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> police itself by recruit<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong>tolaw enforcement, and build<strong>in</strong>g supportive relations with ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority and immigrantcommunities.Once ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g has been recognized as a potential problem, law enforcementauthorities can <strong>in</strong>stitute a number of corrective policies and practices. Actors atevery level of <strong>the</strong> problem— from <strong>European</strong> <strong>Union</strong> officials to national and local politicalleaders; officials of equality, anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation or compla<strong>in</strong>ts-handl<strong>in</strong>g organizations;29

law enforcement leaders and managers, supervisory or operational officers; non-governmentalorganizations and pressure groups; lawyers and academics; and ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orityleaders and community organizations—have a vital role to play <strong>in</strong> undertak<strong>in</strong>g change.This handbook recommends a comprehensive approach to address<strong>in</strong>g ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g—anapproach that seeks to understand all <strong>the</strong> dimensions of <strong>the</strong> problem and todevelop both general and targeted responses. A holistic approach to address<strong>in</strong>g ethnicprofil<strong>in</strong>g will be articulated through national legislation, standards, and strategies orplans that provide a high level of visibility and a clear demonstration of political commitmentto reduce ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, as well as lay<strong>in</strong>g out specific actions to be takenat more local levels. In a holistic approach, each element re<strong>in</strong>forces <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs and aconsistent message is sent to all members of <strong>the</strong> law enforcement <strong>in</strong>stitution, to specificcommunities, and to <strong>the</strong> larger public.Important elements of a holistic approach <strong>in</strong>clude:• Review<strong>in</strong>g legal standards, operational and <strong>in</strong>stitutional practices that contributeto or permit profil<strong>in</strong>g and amend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m to create clear standards and safeguards;• Institut<strong>in</strong>g systems to monitor law enforcement practices to detect profil<strong>in</strong>g;• Build<strong>in</strong>g polic<strong>in</strong>g skills and capacity to operate without profil<strong>in</strong>g;• Initiat<strong>in</strong>g recruitment drives to create diverse law enforcement agencies that representall communities;• Engag<strong>in</strong>g with communities to identify and address local problems and buildtrust.These approaches have <strong>the</strong> dual effect of <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g police efficacy and improv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> quality of ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities’ encounters with law enforcement.In general, mechanisms to address ethnic profil<strong>in</strong>g, like o<strong>the</strong>r police accountabilitymechanisms, function at three dist<strong>in</strong>ct levels: legal and political, <strong>in</strong>stitutionaland managerial, and community-based. These three levels correspond to <strong>the</strong> differentstakeholders <strong>in</strong> law enforcement. 56Law enforcement agencies are accountable to legal standards. They are alsoaccountable to national—and <strong>in</strong> many cases, local—political authorities for <strong>the</strong>ir legalpowers, for policy direction, and for <strong>the</strong>ir budgets.Law enforcement agencies have <strong>in</strong>stitutional mechanisms for managerial andadm<strong>in</strong>istrative accountability that govern officers’ encounters with civilians. These areoften <strong>the</strong> most powerful <strong>in</strong>struments <strong>in</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> daily behavior of law enforcementpersonnel. 5730 A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO REDUCING ETHNIC PROFILING