State of the Parks 2007 - part two - Parks Victoria

State of the Parks 2007 - part two - Parks Victoria

State of the Parks 2007 - part two - Parks Victoria

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Managing threateningprocesses within parksA wide range <strong>of</strong> naturally occurring and human-inducedissues can threaten <strong>the</strong> natural values and condition<strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks.This chapter outlines common issues affecting parks suchas weeds and introduced fauna as well as localised issuesincluding habitat fragmentation, overabundant nativeanimal populations, stock grazing, <strong>the</strong> Phytophthoracinnamomi plant pathogen, <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> park visitorsand authorised uses within parks.The distribution and scale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se issues and <strong>the</strong>irimpacts are described as well as <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’smanagement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m. Results <strong>of</strong> managementand on-going challenges are highlighted throughout.5

5.1 Widespread threatening processesIntroduced plant and animal species are widespread across both public and private landin <strong>Victoria</strong>. While some species have little impact, o<strong>the</strong>rs represent a serious threat to naturaland agricultural values and are so widespread it is impossible to completely eradicate <strong>the</strong>mwith <strong>the</strong> current available technologies.<strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks contain a range <strong>of</strong> introduced plant and animal species. Some threaten<strong>the</strong> viability <strong>of</strong> native species by degrading and displacing native vegetation, preventing <strong>the</strong>regeneration <strong>of</strong> habitat, disturbing soil and promoting erosion and, in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> introducedpredators, preying on vulnerable native animals.To objectively prioritise where control programs are required, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> uses a risk-basedapproach to target areas in parks <strong>of</strong> highest value exposed to <strong>the</strong> greatest threat fromintroduced species, as well as responding to concerns from park neighbours.5This section provides a snapshot <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> introduced species across <strong>Victoria</strong>’sparks and highlights species <strong>of</strong> <strong>part</strong>icular concern. <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s efforts to reduce <strong>the</strong>irimpact, <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> that effort and ongoing challenges are outlined.Chapter<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff removing<strong>the</strong> weed Myrtle-leaf Milkwort(Polygala myrtifolia). 118The feral European rabbit(Oryctolagus cuniculus) is one<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most widely distributedand abundant mammals inAustralia. They build warrenscausing damage to soilstructure and feed on manynative species. 119121VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

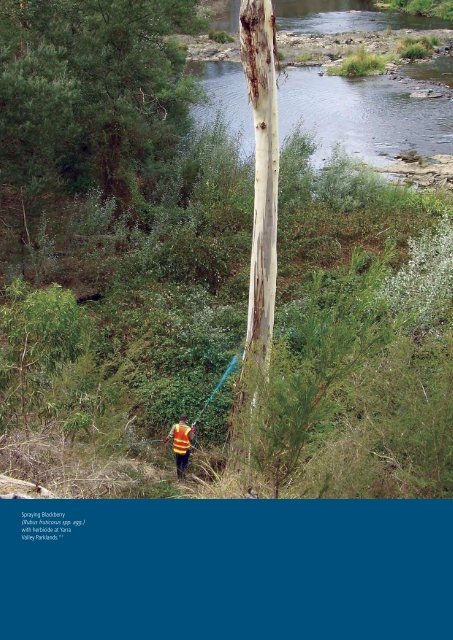

A preliminary weed mapping project conducted by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> in 2005 identified numerous large areas<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parks ne<strong>two</strong>rk where weeds were having limited impact, <strong>part</strong>icularly in <strong>the</strong> less disturbed areas <strong>of</strong> largerparks away from park boundaries, access roads and facilities.Table 5.1CaLP /The occurrence <strong>of</strong> weeds identified by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff as a priority for managementCommon name Scientific name Percentage <strong>of</strong> Percentage Ne<strong>two</strong>rk-widepresent a priority for rank 1 Status 2parks where <strong>of</strong> parks where risk analysis WoNS(n = 332 parks) management(n = 332 parks)BlackberryRubus fruticosus spp.57 48 1 C / Wagg.Bridal Creeper Asparagus asparagoides 29 27 10 C / WPatterson’s Curse Echium plantagineum 27 23 17 CAfrican Boxthorn Lycium ferocissimum 31 21 9 CHorehound Marrubium vulgare 31 20 18 CSt John’s Wort Hypericum perforatum 22 17 16 C5Ragwort Senecio jacobaea 17 13 12 CRadiata Pine Pinus radiata 18 11 14 –Spear Thistle Cirsium vulgare 24 10 13 CChapterSweet Pittosporum Pittosporum undulatum 13 10 8 –Gorse Ulex europaeus 16 9 3 C / WCape Broom Genista monspessulana 14 9 6 CBoneseedChrysan<strong>the</strong>moidesmonilifera subsp.monilifera12 8 5 C / WSerrated Tussock Nassella trichotoma 10 8 2 C / WSweet Briar Rosa rubiginosa 19 8 15 CBlue Periwinkle Vinca major 12 8 11 –English Broom Cytisus scoparius 9 6 4 CChilean Needle-grass Nassella neesiana 7 6 7 C / W1Risk analysis is a preliminary, state-wide assessment based on <strong>the</strong> invasiveness, potential impact on park values and current andpotential distribution <strong>of</strong> each species (Weiss et al., 2003). Ranks are relative only to <strong>the</strong> above list. 2 Noxious weeds listed under <strong>the</strong>Catchment and Land Protection 1994 (Vic) (CaLP Act) are indicated by ‘C’ and Weeds <strong>of</strong> National Significance (WoNS) are indicatedby ‘W’. Note that <strong>Victoria</strong>’s noxious weeds list is under review.Infestation <strong>of</strong> Bridal Creeper(Asparagus asparagoides)in <strong>the</strong> Plenty GorgeBushland Reserve. 120<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff applyingherbicide at <strong>the</strong> Bolin BolinBillabong, Yarra ValleyParklands. 121123 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

Map 5.1 Introduced species in parks5Chapter<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff handpulling weeds in WhipstickGully, Warrandyte <strong>State</strong> Park. 122Grey Sallow Willow(Salix cinerea) infestinga boulder field, AlpineNational Park. 123MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS124

(B) Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> weed control<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s objectives for weed management are to:- eradicate new weed infestations with potential to invade and substantially modify native vegetationcommunities;- control <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> weeds that threaten <strong>part</strong>icular natural values; and- <strong>part</strong>icipate in cooperative programs with land owners to control weeds that threaten economicand/or natural values.<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff reported that weeds were one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> major threats to <strong>the</strong> natural values <strong>of</strong> parks, <strong>part</strong>icularlyto vegetation communities and threatened flora. As it is not possible to control all weeds at all locations,<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> focuses its weed management activities on parks with higher natural values threatened by weeds,as well as parks where weeds may impact on <strong>the</strong> economic values <strong>of</strong> adjacent land. Effective weed control islimited by factors such as suitable control methods and access.A range <strong>of</strong> weed control measures were used in parks throughout this reporting period, ei<strong>the</strong>r individuallyor in combination, including chemical, manual, mechanical and biological control as well as fire. These controlmethods were undertaken by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff and/or contractors in <strong>part</strong>nerships with Friends Groups, volunteergroups, Catchment Management Authorities (CMAs), corporate organisations and o<strong>the</strong>r government agencies.(i) Number and area <strong>of</strong> parks treated to control weeds5ChapterWeed control programs occurred in between 300 and 600 <strong>Victoria</strong>n parks each year during this reporting period,with ongoing control programs in approximately 150 parks, including most national and <strong>State</strong> parks. Between85,000 and 110,000 hectares were treated annually with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> 2003/04, when 62,000 hectares weretreated, due to a necessary redirection <strong>of</strong> resources for <strong>the</strong> alpine fire suppression and recovery. This includedextensive post-fire weed control programs (see Case Study 4.2).Control programs targeting weeds such as Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus spp. agg.), Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea),English Broom (Cytisus scoparius) and Serrated Tussock (Nassella trichotoma) that potentially impact on nearbyagricultural land were undertaken as <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong> Good Neighbour and o<strong>the</strong>r programs. Between 10,000 and 17,000hectares <strong>of</strong> land along <strong>Victoria</strong>n park boundaries were treated annually.Up to 17,000 hectares <strong>of</strong> land along park boundarieswere treated each year to control weeds.(ii) Trend in <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> treated weed infestations<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff reported that infestations <strong>of</strong> 15 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 18 most commonly reported priority weeds had stabilisedor reduced in <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> assessed parks. These included Horehound (Marrubium vulgare), Ragwort (Seneciojacobaea), Gorse (Ulex europaeus), Spear Thistle (Cirsium vulgare), Sweet Briar (Rosa rubiginosa) and ChileanNeedle Grass (Nassella neesiana) which decreased or stabilised in at least 80% <strong>of</strong> parks where <strong>the</strong>y were amanagement priority and a control program was implemented. African Boxthorn (Lycium ferocissimum), Blackberry,Bridal Creeper (Asparagus asparagoides), Cape Broom (Genista monspessulana), English Broom, Serrated Tussockand Sweet Pittosporum (Pittosporum undulatum) decreased or stabilised in at least 60% <strong>of</strong> parks where <strong>the</strong>y werea management priority and treatment occurred. Three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 18 most commonly reported weeds increased.Blue Periwinkle (Vinca major), Radiata Pine (Pinus radiata) and St. Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum) infestationsincreased in more than 60% <strong>of</strong> parks where <strong>the</strong>y were a management priority and a control program wasimplemented.125 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

5.1.2 Introduced faunaIndicatorRationale(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> introduced terrestrial fauna Some introduced animals pose a significant threat to(B) Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> pest animal controlbiodiversity in <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks. To protect natural values inparks it is important to identify those species that pose <strong>the</strong>greatest threat, understand <strong>the</strong>ir distribution and determine<strong>the</strong> most effective methods to minimise <strong>the</strong>ir threat. Theseindicators describe <strong>the</strong> occurrence and distribution <strong>of</strong> aselection <strong>of</strong> introduced animal species, <strong>the</strong> efforts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Parks</strong><strong>Victoria</strong> to control <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> this control.Context5ChapterA diverse range <strong>of</strong> fauna, including mammal, bird, fish and invertebrate species, has been introduced into <strong>Victoria</strong>and is now established in natural environments. These include feral populations <strong>of</strong> domestic animals (eg. cats,goats and dogs) and species that were deliberately or accidentally introduced. Introduced predators such as feralcats and dogs and foxes threaten <strong>the</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> a wide range <strong>of</strong> native fauna, occur in virtually every terrestrialhabitat across sou<strong>the</strong>rn Australia and have contributed to declines and, in some cases <strong>the</strong> extinction <strong>of</strong> nativefauna species. Ground-nesting birds and small to medium-sized mammals (eg. bandicoots and potoroos) are<strong>part</strong>icularly vulnerable and some reptile species are also susceptible to predation. O<strong>the</strong>r introduced species havea significant impact on native vegetation (eg. rabbits, feral goats and pigs) as <strong>the</strong>y can prevent regeneration, spreadweeds and cause soil damage and erosion. In addition to degrading habitat, <strong>the</strong>y also compete with native faunafor resources like food and shelter. Deer which are protected as game species under <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Act 1975 (Vic)can also have detrimental impacts on park values and are <strong>the</strong>refore included in this section.(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> introduced terrestrial faunaForty-five species <strong>of</strong> introduced fauna were reported in parks assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff.(i) Occurrence <strong>of</strong> introduced terrestrial faunaWhile not all 45 species were known to have a significant impact on natural values, eight species were consideredto be <strong>of</strong> major concern (Figure 5.1). The three species most widely reported in assessed parks were foxes (89%),rabbits (75%) and cats (61%). O<strong>the</strong>r introduced fauna included <strong>the</strong> Black Rat, Brown Hare, House Mouse,Common Blackbird, Common Starling, Brown Trout, Carp, Mosquito Fish, <strong>the</strong> European Wasp and feral Bee.The extent <strong>of</strong> introduced species <strong>of</strong> major concern within parks varied with both species and park. Of <strong>the</strong> 359parks assessed, it was estimated that in approximately 50% <strong>of</strong> parks with foxes and dogs and in approximately40% <strong>of</strong> parks with deer and cats, each species occupied at least half <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> park. The extent <strong>of</strong> rabbits,goats, pigs and horses was more variable. These species occupied less than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> park area for <strong>the</strong> majority<strong>of</strong> parks where <strong>the</strong>y occurred.127 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

Figure 5.1The number <strong>of</strong> parks with pest animals (as reported for 359 parks assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff).Species indicated are those considered to pose <strong>the</strong> greatest risk to park values.5(B) Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> pest animal controlSome infestations <strong>of</strong> introduced fauna in <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks do not require control programs as <strong>the</strong>y have limitedimpact on natural values in some parks. Where <strong>the</strong>y do impact however, it may be impossible to control oreliminate all infestations. Control programs <strong>the</strong>refore need to be targeted to parks with <strong>the</strong> highest natural valuesunder <strong>the</strong> greatest threat. Since 2000, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> has developed tools to help identify <strong>the</strong>se areas includingcommissioned studies that identified native fauna species vulnerable to fox predation and <strong>the</strong>ir distribution (Robleyand Choquenot, 2002) as well as <strong>the</strong> susceptibility <strong>of</strong> vegetation communities to disturbance by rabbits (Long etal., 2003). Management programs were also focussed on rabbit and fox control to minimise impacts on naturaland agricultural values <strong>of</strong> land adjacent to parks.ChapterMethods used to control pests included trapping, fencing, poisoning, fumigation, shooting and harbourdestruction. A Memorandum <strong>of</strong> Cooperation with <strong>the</strong> Sporting Shooters Association <strong>of</strong> Australia (<strong>Victoria</strong>) to assistin pest species control was also introduced (see chapter 3, Case Study 3.3).MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS128

<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> rangerinvestigating an area<strong>of</strong> uprooted ground andwallows caused by feralpigs in <strong>the</strong> Mitta area,Alpine National Park. 125(i) Number <strong>of</strong> parks and area <strong>of</strong> parks treated to control pest animals5ChapterThe number <strong>of</strong> parks where pest animal control programs were undertaken varied from a maximum <strong>of</strong> 232 parksin 2001/02 to a minimum <strong>of</strong> 136 in 2003/04. The variation was due to changing levels <strong>of</strong> risk (eg. success <strong>of</strong> rabbithaemorrhagic disease and o<strong>the</strong>r control programs in <strong>the</strong> Mallee), increased targeting to larger scale programsin higher-value parks as well as <strong>the</strong> redirection <strong>of</strong> resources to fire recovery. Between 300,000 and 877,000hectares were treated annually, with a substantial increase after 2001/02 due to <strong>the</strong> start <strong>of</strong> a major fox adaptiveexperimental management (AEM) program in six parks (Case Study 5.2) and involvement in new landscape scalecontrol programs such as Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ark and Glenelg Ark.The most widely targeted species were rabbits and foxes, while o<strong>the</strong>r targeted species included pigs, goats, cats,dogs and <strong>the</strong> European Wasp. Of 359 parks assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff, 55% <strong>of</strong> parks with rabbits, 49%<strong>of</strong> parks with foxes and goats, 36% with dogs, 33% with pigs and 17% with cats were targeted for managementprograms. Of <strong>the</strong> seven parks where horses were recorded one had a management program in place. Deer wererecorded in 115 parks and six parks (5% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se) had a program in place to minimise <strong>the</strong>ir impacts. These speciesmay not have posed a significant risk to native fauna and flora in parks without a control program.Fifty-five parks, including most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> larger national parks were <strong>the</strong> focus for ongoing fox and/or rabbit controlin at least four years from 2000/01 to 2004/05. Good Neighbour and Rabbit Buster cooperative programs targetingfoxes and rabbits were undertaken in between 49 and 94 parks annually to protect agricultural values near parkboundaries.Up to 877,000 hectares and 232 parkswere treated annually to control pest animals.A feral pig trapped in <strong>the</strong>Alpine National Park. 126129 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

5.2 Adaptive experimental management <strong>of</strong> foxesCase StudyIn 2001, a five-year adaptive experimental management (AEM) project was established using existing strategiesemployed to control <strong>the</strong> Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). The objectives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project were to test <strong>the</strong> applicability <strong>of</strong>AEM to broad-scale pest management, examine <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> different spatial and temporal intensities<strong>of</strong> baiting on fox and prey abundance and evaluate <strong>the</strong> costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> each control strategy. Poisonbaiting with 1080 (sodium mon<strong>of</strong>luoroacetate) baits is <strong>the</strong> most common fox control technique employed by<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> and is <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> this project.The sites selected for <strong>the</strong> AEM were <strong>the</strong> Grampians, Wilsons Promontory, Little Desert, Coopracamba andHattah–Kulkyne National <strong>Parks</strong>. Fox activity was measured by bait-take and by using sand-plots to detect foxtracks. Monitoring <strong>of</strong> prey species abundance was performed using various live-trapping survey techniques.By monitoring both foxes and prey, <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> each control strategy in reducing fox abundanceand protecting and enhancing prey populations can be determined. Keeping records <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time and moneyinvested in each control strategy also enables <strong>the</strong> relative efficiency <strong>of</strong> each approach to be evaluated.To date, this project has demonstrated <strong>the</strong> applicability <strong>of</strong> an AEM approach to broad-scale pest managementand <strong>the</strong> initial results have indicated that different temporal intensities <strong>of</strong> baiting vary in <strong>the</strong>ir ability to reducefox activity. Bait-take monitoring data show that annual and pulsed programs are more effective than seasonalprograms. Prey-response data are limited so no conclusions on <strong>the</strong> outcomes <strong>of</strong> management for <strong>the</strong>se speciescan yet be drawn.<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> rangerchecking for fox footprintson a sand-plot. 1275ChapterMANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS130

(ii) Trend in <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> treated pest animal infestations<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff reported that introduced fauna was a major threat to natural values in parks, <strong>part</strong>icularlythreatened fauna. Rabbits and foxes were <strong>the</strong> main focus for control programs. Where control programs wereundertaken, 71% <strong>of</strong> 147 parks with a rabbit control program and 50% <strong>of</strong> 157 parks with a fox program reportedthat populations decreased or stabilised. Staff reported that where populations <strong>of</strong> pigs and goats occurred, <strong>the</strong>yincreased in more parks than decreased or stabilised. Two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more successful goat control programs occurred in<strong>the</strong> Grampians and <strong>the</strong> Murray-Sunset National <strong>Parks</strong>. The trend in <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> introduced animals was unknownfor a high proportion <strong>of</strong> parks, with uncertainty greatest for deer, cats, dogs and foxes. New research andmonitoring programs have begun to provide improved information on <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> introduced fauna.(iii) Trend in <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> treated pest animal infestationsA subset <strong>of</strong> 251 parks were assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff to determine <strong>the</strong> trend in <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> foxes for thisreporting period. Of <strong>the</strong> 251 parks:- 116 parks (46%) had a control program in at least one year from 2000/01 to 2004/05 and 11% (28 parks)had an ongoing program in at least four <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se years;- 58 parks (23%) did not have a control program because foxes were not considered to be impacting on parkvalues; and- 77 parks (31%) did not have a control program and staff reported that foxes impacted negatively on park values.5ChapterOf <strong>the</strong> 116 parks with a control program, <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> foxes stabilised or decreased in 56 parks (48%).Where an ongoing control program occurred in at least four years from 2000/01 to 2004/05 (28 parks)management was more effective with <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> foxes stabilised or decreased in 17 parks (61%).Of <strong>the</strong> 77 parks with no control program, one park (Croajingolong National Park) was identified as a high priorityfor fox control using a state-wide fox risk assessment tool (Robley and Choquenot, 2002). Croajingolong NationalPark has since been incorporated into <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ark fox control program, a collaborative initiative in EastGippsland involving <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>, <strong>the</strong> De<strong>part</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and Environment (DSE), De<strong>part</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> PrimaryIndustries (DPI) and <strong>the</strong> CSIRO.A subset <strong>of</strong> 260 parks were also assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff to determine <strong>the</strong> trend in <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> rabbitsfor this reporting period. Of <strong>the</strong> 260 parks:- 100 parks (39%) had a control program in at least one year from 2000/01 to 2004/05 and 10% (27 parks)had an ongoing program in at least four <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se years;- 99 parks (38%) did not have a control program because rabbits were not impacting on park values; and- 61 parks (23%) did not have a control program and staff reported that rabbits impacted negatively on parkvalues.Of <strong>the</strong> 100 parks with a control program, <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> rabbits stabilised or decreased in 66 parks (66%).Where an ongoing control program occurred in at least four <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> five years during this reporting period (27 parks)management was more effective with <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> rabbits stabilised or decreased in 21 parks (78%).Of <strong>the</strong> 61 parks with no control program, seven parks were identified as high priorities for rabbit control usinga state-wide rabbit risk assessment tool (Long et al., 2003).In some parks <strong>the</strong>re was insufficient information available for staff to determine <strong>the</strong> trend <strong>of</strong> fox and rabbit impactsfollowing control programs. The level <strong>of</strong> uncertainty declined where ongoing programs were operating as more<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se parks had monitoring programs.131 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)with an EasternBarred Bandicoot(Perameles gunnii). 128<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> rangerlaying an oat trail as rabbitbait in Hattah-KulkyneNational Park. 1295ChapterMANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS132

5.2 Localised threatening processesA variety <strong>of</strong> naturally occurring and human-induced processes and activities occurthroughout <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks. These include habitat fragmentation, overabundant nativeanimal populations, stock grazing, <strong>the</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomi plant pathogen and <strong>the</strong>impacts <strong>of</strong> park visitors and authorised uses. While <strong>the</strong>se may be essential activities in manycases, in some parks <strong>the</strong>y may have a localised and detrimental impact on values.This section provides a snapshot <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se processes and activities, highlights <strong>the</strong>ir knownimpacts in parks and describes <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s efforts to reduce <strong>the</strong>ir impact.5ChapterDeath <strong>of</strong> a Grass Tree fromPhytopthora cinnamomi. 130133VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

5.2.1 Habitat fragmentationIndicatorRationale(A) Fragmentation <strong>of</strong> parks by roads and tracks Habitat fragmentation has potential to degrade habitat(B) Managing habitat fragmentationand expose some native species to a variety <strong>of</strong> threats.While roads and tracks in parks can fragment habitat<strong>the</strong>y may also provide essential management access.These indicators describe <strong>the</strong> density <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> road and trackne<strong>two</strong>rk, <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resulting fragments andoutline <strong>the</strong> approach <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> has taken to reducing<strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> fragmentation.ContextMost parks are fragmented to at least some extent by past land use, including <strong>the</strong> clearing <strong>of</strong> native vegetationand <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> infrastructure such as roads, tracks and power easements. While roads and tracks existto provide access for visitors and for emergency and management purposes, <strong>the</strong>y can also change natural habitatsby altering light regimes, micro-climate and water run-<strong>of</strong>f. Reducing fragmentation can:- reduce barriers affecting <strong>the</strong> movement <strong>of</strong> native fauna;- reduce <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> pest plant and animal invasion;- minimise <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomi;- help control erosion; and- generally protect <strong>the</strong> habitat <strong>of</strong> native flora and fauna, including threatened species.While some fragmentation is unavoidable, it is possible in many instances to rehabilitate areas to reduce<strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> fragmentation, especially where <strong>the</strong>se are a legacy <strong>of</strong> past management.5Chapter(A) Fragmentation <strong>of</strong> parks by roads and tracksFragments are created where roads or tracks connect to create isolated areas within parks. The density <strong>of</strong> roadsand tracks can indicate <strong>the</strong> extent to which park values are subject to fragmentation processes.(i) Road and track densityA commissioned study (Milne and Gibson, 2002; 2004) <strong>of</strong> 88 <strong>Victoria</strong>n terrestrial parks reserved under <strong>the</strong> National<strong>Parks</strong> Act 1975 (Vic) revealed:- 23% <strong>of</strong> parks had less than five metres <strong>of</strong> track per hectare, 19% had more than 20 metres <strong>of</strong> track per hectareand six per cent had more than 30 metres <strong>of</strong> track per hectare.- <strong>Parks</strong> with <strong>the</strong> highest track densities tended to be small (less than 4,000 hectares) and included LangwarrinFlora and Fauna Reserve and Churchill, Dandenong Ranges and Terrick Terrick National <strong>Parks</strong>.(ii) Fragment size and density<strong>Parks</strong> with a greater number <strong>of</strong> smaller fragments were generally likely to be more susceptible to <strong>the</strong> impacts<strong>of</strong> fragmentation. The size <strong>of</strong> fragments varied considerably within <strong>the</strong> 88 terrestrial National <strong>Parks</strong> Act parksexamined. Most fragments were small, with 84% <strong>of</strong> fragments covering less than 100 hectares, although <strong>the</strong>seonly represented three per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> parks examined. In contrast, fragments greater than 1,000 hectaresaccounted for four per cent <strong>of</strong> all fragments and represented 83% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area examined.The largest parks were generally among <strong>the</strong> least fragmented, with all parks larger than 30,000 hectares havinga fragmentation density less than 0.34 fragments/km 2 (eg. Alpine, Croajingolong, Murray-Sunset and WyperfeldNational <strong>Parks</strong>). The most fragmented parks were typically smaller, with higher densities <strong>of</strong> fragmentation also morecommon in urban fringe parks (eg. Langwarrin Flora and Fauna Reserve, Dandenong Ranges and Organ PipesNational <strong>Parks</strong> and Warrandyte <strong>State</strong> Park).MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS134

(iii) Threatened vegetation classes affected by fragmentationUnderstanding <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> natural values (in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> ecological vegetation classes – EVCs) and howfragmentation affects <strong>the</strong>m enables those values at greatest risk to be targeted. For example in <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn InlandSlopes Bioregion, 83% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Grassy Woodland EVC (endangered in that bioregion) occurred within fragmentscovering less than 100 hectares. In <strong>the</strong> Goldfields Bioregion, 61% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Box–Ironbark Forest EVC (depleted in thatbioregion) occurred within fragments covering less than 100 hectares. Where possible, fragmentation should bereduced in areas <strong>of</strong> threatened EVCs to increase <strong>the</strong>ir viability.(B) Managing habitat fragmentationReducing <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> fragmentation requires a combination <strong>of</strong> approaches including track closures as wellas managing threats that are exacerbated by fragmentation, such as weed and pest invasion. <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>and its <strong>part</strong>ners have undertaken targeted work to reduce fragmentation in parks.(i) Rationalising roads and tracks in highly fragmented areasWithin <strong>the</strong> new Box–Ironbark parks, strategies to manage <strong>the</strong> potential impact <strong>of</strong> roads, tracks and o<strong>the</strong>rdisturbances were developed through <strong>the</strong> park management planning process. The road and track ne<strong>two</strong>rk wasassessed relative to <strong>the</strong> requirements <strong>of</strong> park users, management and emergency needs and potential impacts onpark values.5ChapterAt Anglesea Heath, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> has been rationalising <strong>the</strong> track ne<strong>two</strong>rk and rehabilitating old gravel extractionsites in <strong>part</strong>nership with Alcoa (Figure 5.2). Prior to <strong>the</strong>se works beginning, Anglesea Heath had approximately297 kilometres <strong>of</strong> tracks throughout its 6,731 hectares, which was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest track densities across<strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks ne<strong>two</strong>rk. By 2005, 112 kilometres <strong>of</strong> tracks and 13 hectares <strong>of</strong> gravel extraction areas wererehabilitated. When work is completed, <strong>the</strong> density <strong>of</strong> tracks in Anglesea Heath will have been reduced from 44to 24 metres per hectare.At Bunyip <strong>State</strong> Park fragmentation has been reduced through initial track closures, guided by <strong>the</strong> managementplan, and more recently a review <strong>of</strong> roads and tracks through a recreation management framework, whichconsidered both <strong>the</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong> park users and protection <strong>of</strong> park values.Figure 5.2Reducing track density at Anglesea Heath: before rationalisation commenced (left) and proposed result (right).135 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

(ii) Revegetation activities undertaken to restore fragmented habitatsTo reconnect and rehabilitate fragmented areas in parks affected by previous land use, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> implementedrevegetation programs across over 2,500 hectares in 67 parks during this reporting period. The largest programsincluded: <strong>the</strong> Urban Biolinks program in Melbourne (Case Study 5.3); various conservation reserves in <strong>the</strong>Wimmera; Hird Swamp in nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Victoria</strong>; Jack Smith Lake in West Gippsland; Yellingbo Nature ConservationReserve, <strong>State</strong> Coal Mine, McLeods and Clydebank Morass in Gippsland; as well as Greater Bendigo National Park,Serendip Sanctuary, <strong>the</strong> You Yangs, Wonthaggi heathland, Mallee parks, and coastal reserves at San Remoand Seaspray.The largest revegetation effort was conducted in 2001/02, with a decline in subsequent years reflecting greateremphasis on weed and pest animal control programs. Measuring <strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong> revegetation programs is achallenge, with limited data on <strong>the</strong> long-term survival <strong>of</strong> revegetation. <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> will continue revegetationprograms in locations where <strong>the</strong>y <strong>of</strong>fer a viable solution to reduce <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> fragmentation on prioritynatural values.Revegetation occurred across 2,500 hectares in 67 parks.5.3 Urban BiolinksCase Study The Urban Biolinks program was established by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> in 1999 to connect remnant patches <strong>of</strong> vegetationto larger core areas <strong>of</strong> habitat in urban and urban fringe parklands it manages. The program targeted openspace corridors in Melbourne’s north and east.From 2000 to 2004, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff and teams <strong>of</strong> volunteers and contractors re-established more than 200hectares <strong>of</strong> indigenous vegetation with 600,000 plants. The parks benefiting from <strong>the</strong> work includedWarrandyte <strong>State</strong> Park, Yarra Valley Parklands, Yarra Bend Park, Plenty Gorge, Lysterfield Park, Dandenong ValleyParklands and Cardinia Creek Parklands. <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> will be working with researchers in <strong>the</strong> future to monitor<strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> revegetation programs as well as <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corridors as wildlife habitat.Newly planted treesin Plenty Gorge Parklands. 131Revegetation work atLake Elingamite, <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Borrell-a-kandelop project torehabilitate <strong>the</strong> internationallysignificant Western DistrictLakes Ramsar site. 1325ChapterMANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS136

5.2.2 Overabundant native animal populationsIndicatorRationale(A) Impact <strong>of</strong> overabundant native animal populations In some circumstances, populations <strong>of</strong> native animals may(B) Minimising <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> overabundantnative animal populationsincrease to such an extent <strong>the</strong>y degrade <strong>the</strong> habitat thatsupports <strong>the</strong>m and management intervention is required.These indicators describe instances where native animalpopulations have reached sufficient numbers to threaten <strong>the</strong>welfare <strong>of</strong> animals as well as <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir habitat.The response <strong>of</strong> <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> to <strong>the</strong>se challenges is alsooutlined.ContextWildlife populations are dynamic in nature and may vary naturally in distribution and over time. While populationsmay have potential for continuous expansion, a range <strong>of</strong> environmental factors generally limit this type <strong>of</strong> growth,such as limited food or habitat, predators and disease. Episodic occurrences <strong>of</strong> extreme temperatures, drought,wildfire or food shortage may also regulate population growth.5ChapterIn park environments where species are <strong>of</strong>ten confined to limited areas bounded by highly modified landscapes,fire is controlled, predator regimes are altered and access to food and water may be increased, populations <strong>of</strong>native species may grow beyond sustainable levels. This can result in habitat degradation and negative impacts ono<strong>the</strong>r native species. A <strong>part</strong>icular species may become so abundant that food resources are completely consumed,resulting in mass starvation. This has occurred to a number <strong>of</strong> koala populations across sou<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Victoria</strong>. This type<strong>of</strong> population fluctuation (expansion and crash) may place natural values that are rare or limited in distribution atrisk as well as pose significant animal welfare concerns. To maximise biodiversity conservation and/or reduce risk <strong>of</strong>large-scale population starvation, human intervention may be needed to control overabundant wildlife populations.(A) Impact <strong>of</strong> overabundant native animal populationsOf 288 terrestrial parks assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff to determine <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> overabundant native animalson o<strong>the</strong>r park values, overabundant kangaroos and koalas were identified as posing some threat to o<strong>the</strong>r naturalvalues in 17% (49 parks). However, <strong>the</strong> impact was considered high in only 6% (19 parks). Birds, bats or o<strong>the</strong>rnative fauna were identified as threatening natural values in 5% (13 parks) with <strong>the</strong> impact considered highin less than 2% (five parks).(i) <strong>Parks</strong> where overabundant kangaroo and koala populations were identified as a threat too<strong>the</strong>r natural valuesThe greatest native animal management challenges currently faced by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> is maintaining low kangaroograzing pressure in <strong>the</strong> Mallee parks and managing <strong>the</strong> koala population at Mount Eccles National Park.An emerging challenge has been to manage sustainable populations <strong>of</strong> kangaroos in some urban fringe parks,<strong>part</strong>icularly to <strong>the</strong> north and west <strong>of</strong> Melbourne in Plenty Gorge Parklands, Woodlands Historic Park and SerendipSanctuary. Overabundant kangaroo populations at Yanakie Isthmus in Wilsons Promontory National Park have alsobeen a significant issue for restoration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Grassy Woodland communities.137 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

(B) Minimising <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> overabundant native animal populations<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> manages overabundant populations to minimise <strong>the</strong>ir impact on o<strong>the</strong>r natural values and to meetcommunity expectations and legislative obligations relating to animal welfare. Population management is onlyperformed when a <strong>part</strong>icular population is:- threatening <strong>the</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> rare or threatened species or communities;- a major contributor to serious environmental damage or long-term degradation <strong>of</strong> habitat;- a major factor preventing habitat recovery; or- suffering as a result <strong>of</strong> confinement.The need to undertake control is documented by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> and reviewed by an independent technical advisorycommittee. Active population management is performed as a last resort and when o<strong>the</strong>r options for riskmanagement are impractical or not feasible. Any action taken must be <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong> an integrated approach, such asreducing <strong>the</strong> total grazing pressure from exotic grazers (eg. rabbits) as well as native species. As <strong>of</strong> 2005,population control was confined to kangaroos and koalas.(i) Activities to achieve sustainable populations<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> implemented population management projects in seven parks during this reporting period to addressovergrazing. The species managed were koala, Eastern Grey Kangaroo, Western Grey Kangaroo and Red Kangaroo.These projects covered between 140,000 and 180,000 hectares annually, with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> 2003/04 when <strong>the</strong>effects <strong>of</strong> drought reduced kangaroo population recruitment and population management was not required.To reduce impacts on coastal woodland communities, koala populations were managed at French Island andMount Eccles National <strong>Parks</strong> (Case Study 5.4), Snake Island (Nooramunga Marine and Coastal Park) and RaymondIsland (Gippsland Lakes Coastal Park) using fertility control techniques or by relocating individuals to o<strong>the</strong>r areas.At Mount Eccles National Park, reducing large koala populations to sustainable densities to prevent ongoing declinein tree condition was not possible with techniques such as relocation. An innovative fertility control trial was<strong>the</strong>refore introduced in 2004 (Case Study 5.4). By mid-2005 1,800 koalas had been treated with contraceptivehormones at Mount Eccles National Park, and at Snake Island 2,000 koalas had been sterilised and 1,000 relocated.A sterilisation and relocation program at Snake Island has been <strong>part</strong>icularly successful to date in substantiallyreducing population growth.5ChapterKangaroo population control was incorporated into managing total grazing pressure in three Mallee parks:Hattah– Kulkyne, Wyperfeld and Murray–Sunset National <strong>Parks</strong>. In <strong>the</strong>se parks, assessments <strong>of</strong> vegetation conditionfollowing kangaroo (and rabbit) control have indicated a positive response from vegetation at several sites despitedrought conditions (see chapter 3, Case Study 3.5). Ongoing monitoring <strong>of</strong> population levels and vegetationresponse is required to ensure <strong>the</strong> long-term viability <strong>of</strong> susceptible vegetation communities.A Manna Gum (centre)defoliated by over-browsingby koalas at Mount EcclesNational Park. 133MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS138

5.4 Managing koalas at Mount Eccles National ParkCase StudyMount Eccles National Park and <strong>the</strong> surrounding woodlands is currently <strong>the</strong> most significantly affected koalaoverbrowsing site in <strong>Victoria</strong>. From 1999 to 2001, approximately 4,000 animals were moved to o<strong>the</strong>r forestareas in south-west <strong>Victoria</strong> and approximately 2,000 female koalas were also surgically sterilised.Translocation from Mount Eccles National Park ceased in 2002 after detailed monitoring <strong>of</strong> relocated animalsindicated high levels <strong>of</strong> mortality at some release sites, even for non-sterilised animals. Monitoring also indicatedthat while <strong>the</strong> population did not increase, translocating large numbers was ineffective in reducing <strong>the</strong>population because <strong>the</strong> koala births were roughly equivalent to mortality plus translocation.In 2004, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> began a large-scale trial <strong>of</strong> contraceptive implants in <strong>the</strong> koala population to determineif this technique would provide <strong>the</strong> solution with lowest risk to animal welfare and ecosystem health. The trialwas undertaken in <strong>part</strong>nership with DSE and <strong>the</strong> Gunditjmara Aboriginal community through <strong>the</strong> Winda MaraAboriginal Corporation.The management-scale trial <strong>of</strong> contraceptive implants for female koalas aims to target a sufficient number<strong>of</strong> females so that natural mortality exceeds koala births, <strong>the</strong>reby reducing population size over time.Koalas are captured by crews assisted by tree climbers and a small slow-release contraceptive implant is insertedunder <strong>the</strong> skin by a veterinary surgeon. A detailed monitoring program is underway to assess koala abundance,survivorship and defoliation levels.5ChapterA veterinary surgeonimplanting a female koalawith a slow-releasecontraceptive as <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong> atrial to manage <strong>the</strong> koalapopulation at Mount EcclesNational Park. 134139 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

5.2.3 Stock grazingIndicatorRationale(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> stock grazing While stock grazing is generally not allowed in national(B) Managing stock grazingparks it is permitted for agricultural purposes in a largenumber <strong>of</strong> reserves and for ecological reasons in one parkand a number <strong>of</strong> reserves. These indicators describe <strong>the</strong>current status <strong>of</strong> stock grazing across <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks and<strong>the</strong> approach <strong>of</strong> <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> to managing this grazing.ContextThree types <strong>of</strong> stock grazing occur in parks:- licensed stock grazing primarily as an agricultural activity for <strong>the</strong> benefit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> licence holders (mostly inreserves);- licensed or contracted stock grazing to meet specific ecological management objectives; and- unlicensed stock grazing, especially in unfenced reserves.<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> seeks to manage licensed and unlicensed stock grazing in parks to minimise any impacts on naturalvalues. Where grazing is permitted in parks this is usually in accordance with recommendations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>nEnvironmental Assessment Council (VEAC) or its predecessors. In a number <strong>of</strong> cases a phase-out program isrecommended, <strong>part</strong>icularly in areas reserved under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Act 1975 (Vic).In some <strong>Victoria</strong>n parks and reserves, maintaining <strong>the</strong> historical grazing regime at a low level is considerednecessary as an interim measure to preserve important ecosystems such as lowland grassland and bird habitats.Native grasslands are <strong>the</strong> most depleted vegetation type in <strong>Victoria</strong>. Only 6% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plains Grassland and ChenopodShrubland ecological vegetation class (EVC) group that existed before European settlement now remains, and 18%<strong>of</strong> this area is protected in parks and reserves. In a few native grasslands, modified historical grazing regimes havebeen used based on scientific advice as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few existing techniques for minimising decline.5Chapter(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> stock grazing(i) <strong>Parks</strong> where licensed stock grazing occurred for commercial purposesAs <strong>of</strong> June 2005, an estimated 500 grazing licences existed across 560 parks and reserves managed by <strong>Parks</strong><strong>Victoria</strong>. Grazing licences existed mostly on conservation reserves. The total area covered by <strong>the</strong>se licencesrepresented a small area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks. As <strong>of</strong> June 2005, <strong>of</strong> those parks managed under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Act<strong>the</strong>re were 52 grazing licences operating across 10 parks - Alpine, Burrowa-Pine Mountain and <strong>the</strong> now GreatOtway National <strong>Parks</strong>, Mt Lawson, Dergholm and Barmah <strong>State</strong> <strong>Parks</strong>, Nooramunga, Discovery Bay and CapeLiptrap Coastal <strong>Parks</strong> and Lake Albacutya Park. Agricultural grazing in some parks was <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>radministrative errors (such as <strong>the</strong> failure to cancel licences when <strong>the</strong> land was included under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong>Act) or was considered acceptable where cleared land was being considered in exchange for more appropriatefreehold land for inclusion in a park.It should be noted that <strong>the</strong> 57 licences to conduct grazing in <strong>the</strong> Alpine National Park that expired in May 2005were not renewed and <strong>the</strong> last four licences that expired in June 2006 were also not renewed. The <strong>Victoria</strong>nGovernment’s decision to not renew grazing licences was <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> many years <strong>of</strong> research that demonstrated<strong>the</strong> detrimental impacts <strong>of</strong> grazing in <strong>the</strong> park (Case Study 5.5). A fur<strong>the</strong>r 37 licences within <strong>the</strong> Greater Bendigo,Heathcote–Graytown and Chiltern–Mount Pilot National <strong>Parks</strong>, Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park,Kooyoora <strong>State</strong> Park, Broken Boosey <strong>State</strong> Park expired in October 2005. Although not <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reportingtimeframe for this edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Parks</strong>, 28 grazing licences on public land incorporated into <strong>the</strong> newGreat Otway National Park will not be renewed after 30 September 2009.MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS140

5.5 Stock grazing in <strong>the</strong> Alpine National ParkCase StudyThe grazing <strong>of</strong> cattle has been associated with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>n high country since <strong>the</strong> 1830s and will continuein <strong>the</strong> high country outside <strong>the</strong> Alpine National Park.The 1940s saw <strong>the</strong> start <strong>of</strong> a systematic scientific investigation into <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> cattle grazing in alpineand sub-alpine ecosystems. This work, and o<strong>the</strong>r research conducted since, clearly demonstrated that cattleaffect alpine and sub-alpine vegetation by altering community composition and structure. Grazing also createsbare ground, spreads pest plants, disturbs soil and causes erosion and may prevent vegetation growth andrecovery. Grazing also poses a threat to several rare and threatened flora, fauna and plant communities.One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more susceptible communities to <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> grazing is bogs. Based on this evidence in 2005,<strong>the</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>n Government decided to not renew grazing licences in <strong>the</strong> Alpine National Park.In Australia, alpine and sub-alpine areas are rare and important landscapes, representing less than 0.1% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>landmass. The Alpine National Park is <strong>Victoria</strong>’s largest and one <strong>of</strong> its most important parks. It protects morethan 66% <strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s alpine and sub-alpine ecological vegetation classes and makes a major contributionto <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> biodiversity with representatives <strong>of</strong> 35% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state’s flora and 34% <strong>of</strong> its fauna species.Water run-<strong>of</strong>f from <strong>the</strong> park supplies 19% <strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s total run-<strong>of</strong>f. Approximately 87% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area that wasavailable for grazing is located within a declared water supply catchment.5An alpine bog that was badlydamaged by cattle tramplingon <strong>the</strong> Bogong High Plains,Alpine National Park. 135Chapter141 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

(ii) <strong>Parks</strong> where grazing occurred as a management tool to preserve native grasslandsMore than 99% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Plains Grassland community has been lost in <strong>Victoria</strong>. Terrick Terrick National Park(3,770 hectares) protects <strong>the</strong> largest contiguous area (over 1,200 hectares) <strong>of</strong> this grassland in <strong>the</strong> state (<strong>Parks</strong><strong>Victoria</strong>, 2004). At Terrick Terrick National Park, <strong>the</strong> grassland has been lightly grazed by sheep since <strong>the</strong> 1880sand provides specific habitat for threatened flora and fauna. Preliminary results from a 10-year monitoring program<strong>of</strong> grazing exclusion in a small area <strong>of</strong> grassland in <strong>the</strong> park has suggested that total grazing exclusion leads tochanges in <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> grassland which may affect <strong>the</strong> habitat for threatened fauna such as <strong>the</strong> Plainswanderer(<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>, 2003a).Craigieburn Grassland Nature Conservation Reserve (340 hectares) protects a significant area <strong>of</strong> Western BasaltPlains Grassland. This community comprises a variety <strong>of</strong> grasses and herbs and provides habitat for a range<strong>of</strong> threatened flora and fauna. Vegetation monitoring has suggested that excluding grazing stock will affect<strong>the</strong> vegetation, with an overall decrease <strong>of</strong> native species cover within <strong>the</strong> Plains Grassland vegetation community(<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>, 2003b).A recent commissioned study (Wong and Morgan, 2005) highlighted that grazing in some lowland nativegrasslands may be detrimental in <strong>the</strong> long-term and that techniques such as fire should be fur<strong>the</strong>r assessed as analternative to stock grazing. The impact and benefits <strong>of</strong> stock grazing in lowland grasslands will be fur<strong>the</strong>r reviewedthrough a grasslands adaptive management program. It is anticipated that in <strong>the</strong> long-term, grazing will be phasedout <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> above parks once o<strong>the</strong>r measures to maintain <strong>the</strong> grasslands values can be successfully implemented.(B) Managing stock grazingLicensed grazing in parks and reserves was managed through <strong>the</strong> Crown land licensing system. Licencees weregenerally issued by DSE with <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> negotiating changes to licence conditions with licensee and relevantstakeholders, and in some cases monitoring <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> grazing. Specific on-ground management includedpolicing and review <strong>of</strong> licence conditions, reviewing stocking rates, maintaining fencing and inspection <strong>of</strong> andremoving illegal grazing. Rehabilitation works were also performed to protect vulnerable areas from <strong>the</strong> impacts<strong>of</strong> grazing. Several projects were initiated through <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s research program to investigate <strong>the</strong> impactsand rationale <strong>of</strong> licensed grazing to maintain natural values. Outcomes <strong>of</strong> this research will help evaluate <strong>the</strong>ongoing need for licensed grazing in some parks for protecting natural values.5ChapterMANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS142

5.2.4 Phytophthora cinnamomiIndicatorRationale(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomi Many native flora species are susceptible to <strong>the</strong> pathogen(B) Minimising <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomi Phytophthora cinnamomi, which has potential to occur overlarge <strong>part</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state. Strict control methods are requiredto minimise its spread. These indicators identify those parkswith Phytophthora cinnamomi and those at high risk.<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s efforts to minimise spread are also outlined.ContextPhytophthora cinnamomi (PC) is a soil-inhabiting water mould that rots <strong>the</strong> roots <strong>of</strong> many Australian native speciesand is believed to have been introduced into Australia during European settlement. The disease has since spreadto infect large areas <strong>of</strong> remnant vegetation in <strong>the</strong> south-west <strong>of</strong> Western Australia, south-east Australia and <strong>the</strong>coastal areas <strong>of</strong> New South Wales and sou<strong>the</strong>rn Queensland.5ChapterIn <strong>Victoria</strong>, <strong>the</strong> disease impacts on <strong>the</strong> structure and composition <strong>of</strong> vegetation communities by causing dieback<strong>of</strong> some plant species. The active disease front, with brown and yellow vegetation, is <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> most obvious signan area is infected. Once <strong>the</strong> pathogen is established in a susceptible community <strong>the</strong>re is no known means <strong>of</strong>eradication. Vegetation dieback caused by PC is listed as a key threatening process at a national and state level.The spread <strong>of</strong> PC from infected sites into parks, and <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> PC-infected gravel in construction <strong>of</strong> roads, bridgesand reservoirs are listed as potentially threatening processes. <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> has a policy in place to minimise <strong>the</strong>spread <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pathogen in parks.A boot cleaning station in <strong>the</strong>Brisbane Ranges National Park,designed to stop <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong>Phytopthora cinnamomi. 136(A) Distribution <strong>of</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomiA review conducted in 2002 to determine <strong>the</strong> actual and potential distribution <strong>of</strong> PC dieback and to develop a riskrating for 85 parks (Map 5.2) identified environmental factors that contribute to <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pathogen aswell as locations infected by PC (University <strong>of</strong> Ballarat, 2002a). The review found that PC had <strong>the</strong> potential to occurover a large proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> (60%) and in a significant proportion <strong>of</strong> parks. Arid areas in <strong>the</strong> north-west <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> state are generally too dry (< 500mm annual rainfall) and alpine environments (> 800m) are too cold for <strong>the</strong>pathogen to survive.(i) <strong>Parks</strong> where Phytophthora cinnamomi was a risk to native vegetationApproximately 40% (by area) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 85 parks assessed had a climate and elevation within <strong>the</strong> range required forPC dieback. Of <strong>the</strong>se, 69% (59 parks) had some area classified as high risk and 44% (37 parks) had more thanhalf <strong>the</strong>ir area classified as high risk (Map 5.2). Eighteen parks where <strong>the</strong> disease had not previously been recordedhad considerable areas classified as high risk (more than 50%). A large proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> locations <strong>of</strong> several rareand threatened plant species considered susceptible to PC were in areas classified as high risk. High averagenumbers <strong>of</strong> susceptible species generally occurred in communities with a heathy understorey.143 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

The pathogen was recorded in 15 national parks, nine <strong>State</strong> parks and six o<strong>the</strong>r parks. Of <strong>the</strong>se, 57% (17 parks)had more than half <strong>the</strong>ir area classified as high risk and 37% (11 parks) had a high proportion <strong>of</strong> susceptiblespecies (≥10% <strong>of</strong> all species in <strong>the</strong> park) and high risk vegetation in more than half <strong>the</strong> park. The 11 parks were:Brisbane Ranges, Dandenong Ranges, Kinglake and Lower Glenelg National <strong>Parks</strong>; Angahook–Lorne (now <strong>part</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Great Otway National Park), Bunyip, Carlisle, Dergholm, Langi Ghiran and Lerderderg <strong>State</strong> <strong>Parks</strong>; and SteiglitzHistoric Park.Map 5.2 Phytophthora cinnamomi risk within <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks5Chapter(B) Minimising <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomi<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> in association with DSE has provided input into <strong>the</strong> national Threat Abatement Plan for Diebackcaused by <strong>the</strong> root-rot fungus, Phytophthora cinnamomi (Environment Australia, 2001). In 2002, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>commissioned a report to provide guidelines for its best-practice management (University <strong>of</strong> Ballarat, 2002b).The report recommended each park be classified as potentially susceptible or not susceptible based on <strong>the</strong> presence<strong>of</strong> susceptible plant communities, that disease risk ratings be applied and protectable areas identified. Hygieneprocedures for operational and maintenance activities were also outlined.(i) Activities to reduce <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> Phytophthora cinnamomiOf <strong>the</strong> 37 parks with more than half <strong>the</strong>ir area classified at high risk from PC, <strong>the</strong>re were operational guides orhygiene plans in place to minimise its spread in four (Brisbane Ranges and Mornington Peninsula National <strong>Parks</strong>,Lerderderg <strong>State</strong> Park and Steiglitz Heritage Park). An additional 14 parks had strategies to manage PC within <strong>the</strong>irpark management plans. Specific operational guides or hygiene plans will be required in o<strong>the</strong>r parks with PCand those identified at high risk from it. Risk classification ratings have also been linked to <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong>susceptible ecological vegetation classes (EVCs) and rare and threatened flora to guide hygiene requirementsduring operational management and recreation and research activities. Implementing <strong>the</strong> guides will help contain<strong>the</strong> disease.MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS144

5.2.5 Impacts <strong>of</strong> visitor activitiesIndicatorRationale(A) Nature and distribution <strong>of</strong> visitor impacts <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parks ne<strong>two</strong>rk attracts millions <strong>of</strong> visits each year(B) Providing sustainable recreation opportunities and most parks are highly accessible for a wide variety <strong>of</strong>recreational and educational activities. Some recreationalactivities can place pressures on <strong>part</strong>icular natural values.These indicators describe <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> visitor activities in anumber <strong>of</strong> parks and <strong>the</strong> efforts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> to providesustainable experiences for visitors.Context5<strong>Parks</strong> received nearly 43 million visits in 2004/05 (see chapter 7) and <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> people visiting <strong>Victoria</strong>’s parkshas grown substantially since 2000. Many park visitor sites, both in urban areas as well as at major tourist sites,have been designed for sustainable visitor use. While <strong>the</strong>re are limited data on <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> recreational activitiesin <strong>Victoria</strong>n parks, research from o<strong>the</strong>r park agencies has demonstrated that impacts can include trampling <strong>of</strong> soils,vegetation and intertidal communities, reduced water quality, spread <strong>of</strong> weeds, changes in vegetation communitiesthrough activities such as firewood and flora collection, changes in wildlife breeding habits through noise anddisturbance, impacts from motor vehicles and noise that reduces park amenity.(A) Nature and distribution <strong>of</strong> visitor impactsChapterMost visitor activity in <strong>Victoria</strong>n parks is concentrated at serviced areas or along access roads and tracks within <strong>the</strong>irboundaries and impacts on natural values are relatively low where <strong>the</strong>se sites are appropriately designed. Manyparks in <strong>the</strong> urban area are well suited to high concentrations <strong>of</strong> visitors due to <strong>the</strong>ir lower natural values anddeveloped facilities. Impacts in parks associated with activities such as walking, picnicking and riding are <strong>of</strong>tenconfined to <strong>the</strong> immediate area and can be minimised through good design and site or trail hardening. Of moreconcern are <strong>the</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> some activities on natural values away from hardened sites or trails, and inappropriateand unsustainable behaviour.(i) <strong>Parks</strong> where visitors impacted on natural valuesOf 288 parks assessed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff for impacts on natural values, 23% (65 parks) reported no impactfrom visitor activities. Where impacts were recorded, those impacts were considered to be low in <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong>cases. Instances <strong>of</strong> high impact on some environmental values were recorded in 14% (40 parks) <strong>of</strong> those assessedand <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se resulted from inappropriate behaviour and were <strong>of</strong>ten localised. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mostcommonly reported activities that affected natural values included <strong>of</strong>f-road driving, riding or walking, resulting in<strong>the</strong> disturbance and trampling <strong>of</strong> vegetation, soil erosion and <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong> new trails that provide access forweeds, pest animals and plant pathogens. Removing vegetation for firewood, poaching and collecting species aswell as illegal hunting also had some impact in some parks, <strong>part</strong>icularly in central <strong>Victoria</strong>.Activities such as inappropriate rubbish disposal and recreational activities such as climbing, boating and fossickingwere considered to be impacting on natural values in a few parks. Boating was <strong>of</strong> <strong>part</strong>icular concern in parks along<strong>the</strong> Murray River, causing bank modification and erosion. Impacts <strong>of</strong> boating were also reported for parks in <strong>the</strong>marine environment where anchoring and disposal <strong>of</strong> rubbish at sea can affect marine habitats. In intertidalenvironments <strong>of</strong> marine protected areas, <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> staff reported trampling <strong>of</strong> sensitive communities,disturbance <strong>part</strong>icularly <strong>of</strong> birds and in some cases <strong>the</strong> complete removal <strong>of</strong> species. In a few parks vandalismand <strong>of</strong>f-road driving were reported as impacting on geomorphologic features.145 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT

(B) Providing sustainable recreation opportunities<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s Levels <strong>of</strong> Service framework (see chapter 7, section 7.3) has provided directions for <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong>acceptable modification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural environment for recreational purposes. It defines <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> access andexperiences available to visitors at <strong>part</strong>icular sites, as well as <strong>the</strong> types <strong>of</strong> site hardening required to deliver thoseexperiences sustainably. A range <strong>of</strong> tools and programs have been used to ensure sustainable recreationalopportunities are available to park visitors. These have included:- delineating specific visitor sites and management zones in park management plans;- replacing old infrastructure such as septic toilet systems to improve water quality;- constructing sympa<strong>the</strong>tic structures such as board walks over sensitive vegetation;- using permit systems in some parks to ensure a sustainable number <strong>of</strong> visitors;- enforcing appropriate use where necessary;- communicating how to reduce visitor impacts using signs within parks, education programs and speakingto recreational groups; and- redirecting visitor use away from highly sensitive areas to more sustainable sites.(i) Activities to monitor <strong>the</strong> sustainable use <strong>of</strong> parksIn some parks, monitoring programs have been implemented to measure trends in impacts <strong>of</strong> visitor activitiesor to measure environmental responses to management initiatives. Of 223 parks where visitor activities wereidentified as impacting on natural values, 12% (26 parks) had some form <strong>of</strong> systematic monitoring to assess thoseimpacts. <strong>Parks</strong> with formal monitoring programs included Port Campbell and Grampians National <strong>Parks</strong>. Of thoseparks where visitors were considered to have a high impact on natural values (less than 40 parks), few hadmonitoring programs. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se parks have since been targeted for assessment <strong>of</strong> impacts.Environmentally sustainable recreational opportunitiesare guided by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>’s Levels <strong>of</strong> Service framework.5ChapterThe board walk on <strong>the</strong>Button Grass Nature Walk,Bunyip <strong>State</strong> Park is anexample <strong>of</strong> methods usedto reduce visitor impacts. 137Providing visitors withmodern toilet facilities on <strong>the</strong>Errinundra Rainforest Walk inErrinundra National Park. 138MANAGING THREATENING POCESSES WITHIN PARKS146

5.2.6 Utilities, mining and o<strong>the</strong>r authorised usesIndicatorRationale(A) Managing authorised uses A variety <strong>of</strong> authorised uses and infrastructure occurwithin parks including services for power, water andtelecommunications, mining leases and licences, andapiculture (beekeeping). This indicator describes <strong>the</strong>occurrence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se activities and <strong>the</strong> process to ensureimpacts on park values are minimised.ContextWhile parks are set aside primarily for conservation and recreation, it is sometimes not feasible or possible to locatestructures or carry out certain activities outside parks. Examples <strong>of</strong> authorised uses and activities within parksinclude siting <strong>of</strong> infrastructure, mineral and petroleum exploration and mining and apiculture. Where possible,<strong>the</strong> impact on a park is minimised or eliminated by assessing alternative means, location and design. Wherealternative means are unavailable, formal consent is required.5ChapterIn <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> applications for exploration and mining, a rigorous process involving detailed risk assessmentsto determine impacts on park values is required. For parks scheduled under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Act, approval <strong>of</strong>applications is given by <strong>the</strong> Minister for Environment following advice from <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Advisory Counciland tabling in both houses <strong>of</strong> Parliament. For <strong>the</strong> reporting period <strong>of</strong> this edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Parks</strong>, applicationsfor exploration and mining on o<strong>the</strong>r Crown land were referred to <strong>the</strong> relevant Minister (i.e. Planning orEnvironment, depending on land tenure) and were administered by <strong>the</strong> De<strong>part</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> Primary Industries (DPI)under <strong>the</strong> Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 (Vic). Strict conditions to protect values within allpark types are also applied.Apiculture has had a long history in a number <strong>of</strong> parks. The industry is responsible for <strong>the</strong> commercial production<strong>of</strong> honey, pollen, beeswax and related products and is a significant component <strong>of</strong> regional economies. The activityis practised on a range <strong>of</strong> public land types (eg. <strong>State</strong> forest, Crown Land Reserves, national and <strong>State</strong> parks).Apiculture is permitted in parks where authorised by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>n Government on <strong>the</strong> recommendations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Victoria</strong>n Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC) although is prohibited in Wilderness <strong>Parks</strong> and Zones andReference Areas. Sites on land managed under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Act are generally restricted to areas well awayfrom those normally frequented by <strong>the</strong> public.(A) Managing authorised uses(i) Consents to develop infrastructure in parksAs <strong>of</strong> June 2005, <strong>the</strong>re were 92 consents current across 28 parks reserved under <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> Actfor <strong>the</strong> construction and/or operation <strong>of</strong> infrastructure by public authorities. The most common facility wastelecommunication infrastructure such as towers, repeater stations, service buildings and underground cables(66%). O<strong>the</strong>r common consents were for water, sewage and electricity utilities. The Yarra Ranges, Alpine andMornington Peninsula National <strong>Parks</strong> and Lerderderg <strong>State</strong> Park accounted for 40% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 92 consents. Limiteddata was available for authorised uses in reserves.147 VICTORIA’S STATE OF THE PARKS REPORT