The Ecology of Wild Horses and their Environmental ... - Parks Victoria

The Ecology of Wild Horses and their Environmental ... - Parks Victoria

The Ecology of Wild Horses and their Environmental ... - Parks Victoria

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

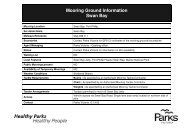

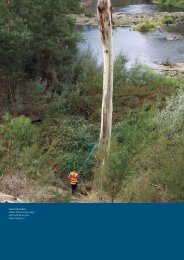

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Background Paper 1 <strong>of</strong> 3<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>nAlps<strong>Wild</strong> horse exclusion plot, Native Cat Flat 2004 (source: <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>).<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>May 2013This paper was written by: Joanna Axford 1 , Michelle Dawson 2 <strong>and</strong> Daniel Brown 31 Formerly <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>, Bright2 Eco Logical Australia3 <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>, BrightAcknowledgements: Arn Tolsma <strong>and</strong> Nick Clemann (Arthur Rylah Institute for <strong>Environmental</strong> Research,DEPI) provided content <strong>and</strong> reviewed this paper. Charlie Pascoe, Dave Foster <strong>and</strong> Mike Dower (<strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>)provided information on wild horse impacts in the Alpine National Park, <strong>and</strong> Malcolm Kennedy (formerly <strong>Parks</strong><strong>Victoria</strong>) reviewed this paper. Joanne Lenehan, PhD c<strong>and</strong>idate (University <strong>of</strong> New Engl<strong>and</strong>), providedunpublished results <strong>of</strong> her study into wild horse impacts in Guy Fawkes River National Park. Alison Matthews(Charles Sturt University), Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor J. Gilkerson (Equine Infectious Disease Laboratory, University <strong>of</strong>Melbourne) <strong>and</strong> H. Crabb (Principal Veterinary Officer-Intensive Farming Systems, DEPI <strong>Victoria</strong>) wereconsulted on various sections <strong>of</strong> this paper.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Acronym ListABA: Australian Brumby AllianceABMA:AALC:AANPs:ANP:BAW:COP:DEPI:Alpine Brumby Management AssociationAustralian Alps Liaison CommitteeAustralian Alps National <strong>Parks</strong>Alpine National ParkBureau <strong>of</strong> Animal WelfareCode <strong>of</strong> PracticeDepartment <strong>of</strong> Environment <strong>and</strong> Primary IndustriesEPBC: Environment Protection <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999FFG: Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Guarantee Act 1988KNP:RSPCA:SOP:VBA:Kosciuszko National ParkRoyal Society for the Prevention <strong>of</strong> Cruelty to AnimalsSt<strong>and</strong>ard Operating Procedure<strong>Victoria</strong>n Brumby Association

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Table <strong>of</strong> ContentsIntroduction to <strong>Wild</strong> Horse Background Papers ..................................................................................... 11. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 22. <strong>Wild</strong> horse ecology in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps ........................................................................................ 23.1 <strong>Wild</strong> horse distribution ........................................................................................................... 23.2 <strong>Wild</strong> horse population trends ................................................................................................. 33.3 <strong>Wild</strong> horse demography .......................................................................................................... 63.4 <strong>Wild</strong> horse social organisation <strong>and</strong> movement ...................................................................... 63.5 <strong>Wild</strong> horse habitat <strong>and</strong> diet preferences ................................................................................ 73.6 <strong>Wild</strong> horse mortality factors ................................................................................................... 83. <strong>Wild</strong> horse environmental impacts ................................................................................................. 93.1 <strong>Environmental</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses .................................................................................... 93.2 Impacts on soil <strong>and</strong> substrate ............................................................................................... 113.3 Impacts on vegetation .......................................................................................................... 143.4 Impacts on peatl<strong>and</strong>s ............................................................................................................ 183.5 Impacts on waterways (streams <strong>and</strong> stream-banks) ............................................................ 203.6 Impacts on fauna .................................................................................................................. 224. <strong>Wild</strong> horse biosecurity issues ........................................................................................................ 255. Gaps in knowledge ........................................................................................................................ 26References ............................................................................................................................................ 27Appendix 1: Officially listed plant ecological communities at risk <strong>of</strong> severe damage from wild horseactivity ................................................................................................................................................... 36Appendix 2: FFG-listed <strong>and</strong> EPBC-listed plant species potentially at risk from wild horse activity in theeastern <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps ........................................................................................................................... 37Appendix 3: Officially listed or threatened fauna species potentially at risk from feral horse activity inthe eastern <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps ..................................................................................................................... 39

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Introduction to <strong>Wild</strong> Horse Background Papers<strong>Horses</strong> (Equus caballus) living in unmanaged, wild populations in Australia are generally known by three terms;feral horses, wild horses <strong>and</strong> brumbies. Any introduced domestic animal that lives in unmanaged, selfsustaining, wild populations is by definition a feral animal. However, some people are uncomfortable with theterm ‘feral’ being associated with horses <strong>and</strong> prefer the terms ‘wild horse’ or ‘brumby’. ‘Brumby’ is a colloquialterm <strong>of</strong>ten used in Australian folklore; however some people believe the term elicits a romanticised view <strong>of</strong>horses <strong>and</strong> detracts from <strong>their</strong> environmental impacts. In this series <strong>of</strong> papers the term ‘wild horse’ will beused, as it is a generally accepted term <strong>and</strong> clearly refers to un-domesticated horses living in the wild.<strong>Horses</strong> were introduced to Australia by early European settlers <strong>and</strong> Australia now has the highest population<strong>of</strong> wild horses in the world, with more than 300 000 (Dobbie et al. 1993). <strong>Wild</strong> horses are a pest species inAustralia, that is, an “animal that has, or has the potential to have, an adverse economic, environmental orsocial/cultural impact” (Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council 2007).<strong>Wild</strong> horses occur across the Australian Alps <strong>and</strong> have been identified as a high priority threat to naturalvalues <strong>of</strong> the region (Coyne 2001). <strong>The</strong> “degradation <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> habitat caused by feral horses” is listed as apotentially threatening process under <strong>Victoria</strong>’s Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Guarantee Act (1988).In <strong>Victoria</strong>, wild horses occur within the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, with a smaller population present in the Barmah Forest(Wright et al. 2006). This series <strong>of</strong> three Background Papers will focus on wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps(Alpine National Park (ANP) <strong>and</strong> surrounding State forests).<strong>The</strong> Background Papers investigate the ecology, environmental impacts, human dimensions <strong>and</strong> management<strong>and</strong> control <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. <strong>The</strong>y are arranged in the following order:Background Paper 1: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. <strong>The</strong> firstsection <strong>of</strong> this paper considers the ecological dimensions <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps including <strong>their</strong>distribution, population trends, demography, habitat, diet <strong>and</strong> mortality factors. <strong>The</strong> environmental impacts <strong>of</strong>wild horses within the region are then considered including <strong>their</strong> impacts on: soil <strong>and</strong> substrate, vegetation,peatl<strong>and</strong>s, waterways <strong>and</strong> fauna. Biosecurity issues are also discussed.Background Paper 2: <strong>The</strong> Human Dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> Horse Management in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. This paperprovides the social context for wild horse management in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. A brief history <strong>of</strong> wild horses inthe region <strong>and</strong> the major stakeholder groups involved is outlined. <strong>The</strong> socio-economic <strong>and</strong> cultural heritagevalues <strong>of</strong> wild horses are then explored followed by a discussion on public perceptions about wild horses <strong>and</strong><strong>their</strong> management in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. Research from national <strong>and</strong> international investigations intoperceptions towards wild horses is drawn upon to help unravel the complexity <strong>of</strong> this value-laden issue.Background Paper 3: <strong>Wild</strong> Horse Management <strong>and</strong> Control Methods. This paper considers the management <strong>of</strong>wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps <strong>and</strong> considers control methods for managing wild horses. An overview <strong>of</strong> howwild horses have been managed in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps <strong>and</strong> the legislation <strong>and</strong> policy framework for wild horsemanagement is provided. <strong>The</strong> paper explores welfare issues <strong>and</strong> costs associated with wild horse control,levels <strong>of</strong> control <strong>and</strong> control options.This series <strong>of</strong> papers was prepared based on available literature <strong>and</strong> research, <strong>and</strong>, through consultation withexperts where possible. <strong>The</strong> papers provide a foundation for discussion concerning the future management <strong>of</strong>wild horses within the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps.1

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 20131. IntroductionIn <strong>Victoria</strong> wild horses (Equus caballus) occur in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps with a smaller population present in theBarmah Forest, on the Murray River (Menkhorst 1995; Wright et al. 2006). <strong>Wild</strong> horses are considered asignificant environmental threat to the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps (including the Alpine National Park (ANP) <strong>and</strong> adjacentState forests). <strong>The</strong> “degradation <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> habitat caused by feral horses” is listed as a potentially threateningprocess under <strong>Victoria</strong>’s Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Guarantee Act (1988). This paper will explore the ecologicaldimensions <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps <strong>and</strong> the extent to which they are affecting the natural values <strong>of</strong>the region.Several studies <strong>and</strong> reviews have been conducted on the ecology <strong>and</strong> environmental impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses invarious parts <strong>of</strong> the Australian Alps, including: Dyring 1990; Thiele & Prober 1999a, 1999b; Walter 2002, 2003;Walter & Hone 2003; Montague-Drake 2005; Prober & Thiele 2007; Nimmo & Miller 2007; Laake et al. 2008;Dawson 2005, 2009a, 2009b; <strong>and</strong> Venn et al. 2009. To help unravel the significance <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the<strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, information in this paper is also drawn from national <strong>and</strong> international literature as well asanecdotal information on wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps.2. <strong>Wild</strong> horse ecology in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps3.1 <strong>Wild</strong> horse distribution<strong>Wild</strong> horses in the Australian Alps are relatively isolated from populations elsewhere in Australia. <strong>The</strong> largestpopulations in Australia occur in dry <strong>and</strong> tropical environments, mainly in the Northern Territory <strong>and</strong>Queensl<strong>and</strong>, but also Western Australia <strong>and</strong> South Australia (Dobbie et al. 1993). In much <strong>of</strong> Australia, droughtlimits the distribution <strong>of</strong> wild horses (Dobbie et al. 1993). However, this is not evident in the Australian Alpswhich occupy wetter bioregions with more consistent rainfall (Hobbs & McIntyre 2005). <strong>The</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong>wild horses in Australia has also been strongly influenced by human intervention including farminginfrastructure such as fencing (McKnight 1976).<strong>Wild</strong> horses were initially introduced into the Australian Alps by European settlers in the 1830s. Graziersmanaged the distribution (<strong>and</strong> numbers) <strong>of</strong> wild horses to varying degrees from the mid-1800s up until cattlegrazing ceased early this century (Walter 2002; Foster 2004). Non-human influences on wild horse distributionin the Alps include preferred habitat, geographical barriers <strong>and</strong> natural events such as severe snow storms, fire<strong>and</strong> drought (Walter 2002). Between 1990 (Dyring 1990) <strong>and</strong> 2002 (Walter 2002) wild horse distributionappeared to be relatively stable in the ANP, however, in the past ten years wild horse populations haveexp<strong>and</strong>ed <strong>their</strong> range in a number <strong>of</strong> locations, including spreading to new locations on the Bogong High Plains(Dawson 2009). Dawson (2009) also suggests that there is suitable habitat for wild horses in Australian Alpsthat is currently not occupied. Furthermore, it is predicted that with climate change, areas at higher elevationwill become more suitable for wild horses (Dunlop & Brown 2008; Green & Pickering 2002).<strong>The</strong> largest population <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps is in the eastern Alps (east <strong>of</strong> Omeo) <strong>and</strong> isconnected to a population in Kosciuszko National Park, NSW to the north (Figures 1 <strong>and</strong> 2). It extends south tothe Nunniong Plains, as far west as Mt Pinnibar <strong>and</strong> Buenba Creek, <strong>and</strong> to Deddick <strong>and</strong> Amboyne east <strong>of</strong> theSnowy River. <strong>The</strong> second, smaller population is on the southern Bogong High Plains, between Falls Creek <strong>and</strong>Mount Hotham, <strong>and</strong> in the headwaters <strong>of</strong> the Cobungra, Bundara <strong>and</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> Rivers (Ethos NRM 2012). <strong>The</strong>Bogong High Plains/Cobungra population is isolated from the Eastern Alps population by around 30km <strong>and</strong>considered to have a lower density <strong>of</strong> horses than the east Alps population (Ethos NRM 2012) (figure 2). Bothpopulations, while situated predominantly within the ANP, extend into adjacent State forests <strong>and</strong> reserves<strong>and</strong>, probably, private l<strong>and</strong>.2

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Records <strong>of</strong> small groups <strong>of</strong> horses have occurred at other disjunct locations across the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps from timeto time, however these isolated records are considered not represent extant populations.In spring 2009 a group <strong>of</strong> 18 wild horses was discovered in the headwaters <strong>of</strong> the Moroka River, near MtWellington in the Alpine National Park <strong>and</strong> the adjacent Carey State Forest. This group <strong>of</strong> horses is suspectedto have been illegally introduced, but was gradually trapped <strong>and</strong> removed by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> <strong>and</strong> DEPI over thesubsequent summer <strong>and</strong> autumn. In early winter 2010, another new group was discovered in State forest atConnors Plain, north-west <strong>of</strong> Licola. This group was also trapped <strong>and</strong> removed. Monitoring continues in bothareas to ensure that all the horses have been captured.Mount BuffaloNational ParkAlpine National ParkAlpine National ParkAlpine National ParkSnowy RiverNational ParkFigure 1: Estimated wild horse distribution in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, showing the two disjunct populations. This distributionmap is based on a report by Ethos NRM (2012) that used previous horse records <strong>and</strong> interviews with a broad range <strong>of</strong>stakeholders (with knowledge <strong>and</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps) to estimate the distribution <strong>of</strong> wildhorses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps. NB: This map is based on anecdotal qualitative information <strong>and</strong> provides only a broad guide towild horse distribution.3.2 <strong>Wild</strong> horse population trends<strong>The</strong> most reliable estimates <strong>of</strong> wild horse population size have come from aerial surveys across the AustralianAlps National <strong>Parks</strong> (AANPs) conducted in 2001, 2003 <strong>and</strong> 2009 (Walter & Hone 2003; Dawson 2009). <strong>The</strong>sesurveys were developed with the aim <strong>of</strong> providing a repeatable <strong>and</strong> robust method for monitoring wild horsepopulation size in parts <strong>of</strong> the AANPs (not including adjacent areas such as State forests <strong>and</strong> private l<strong>and</strong>)(Walter & Hone 2003). Surveys are conducted from a helicopter at a fixed-height <strong>and</strong> speed along east-westtransects at two kilometre intervals <strong>and</strong> analysed using line-transect techniques (Walter & Hone 2003). Thismethod was designed to minimise several potential sources <strong>of</strong> bias such as decreasing detectability <strong>of</strong> horseswith distance from the aircraft (Walter & Hone 2003), <strong>and</strong> counting horses more than once (see Linklater &Cameron 2002).3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013140120Estimated Horse Population<strong>Horses</strong> Removed100Number <strong>of</strong> <strong>Horses</strong>8060405537 383120010116792 95 88 512005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012YearFigure 4: Estimates <strong>of</strong> wild horse population size ± SE for the Bogong High Plains population only. <strong>The</strong> number <strong>of</strong> horsesremoved from these areas by <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> since 2005 is also included (red columns). Population estimates are derivedfrom aerial surveys (Dawson <strong>and</strong> Miller 2008).3.3 <strong>Wild</strong> horse demography<strong>Wild</strong> horses have an annual breeding season, producing one young at a time (Grange et al. 2009). <strong>The</strong> firstyoung are usually produced when females are three years <strong>of</strong> age. When wild horse density is low <strong>and</strong> food isabundant they occasionally reproduce at two years <strong>of</strong> age (Berger 1986; Duncan 1992). During a three yearstudy from 1999 to 2002, the youngest mare observed with a foal in the Australian Alps was three years old(Dawson & Hone 2012). Foaling rates increase up to the age <strong>of</strong> five <strong>and</strong> mares continue to have high foalingrates until the onset <strong>of</strong> senescence at 15-18 years <strong>of</strong> age (Garrott & Taylor 1990; Garrott et al. 1991b; Duncan1992; Linklater et al. 2004; Grange et al. 2009). Foals are usually born in the summer months when foodavailability is at its highest (after an 11 month gestation) but can be born at any time <strong>of</strong> year (Dawsonunpublished data). Foaling rates observed for wild horses in three separate populations in the Australian Alpsbetween 1999 <strong>and</strong> 2002 were lower than those reported in other environments with 42-62% <strong>of</strong> adult femalesobserved with foals (Dawson & Hone 2012).Between 1999 <strong>and</strong> 2002 survival rates <strong>of</strong> adult wild horses in the Australian Alps were generally high (91% perannum) with little annual variation, while survival rates in the first three years <strong>of</strong> life are lower <strong>and</strong> morevariable (63-75% per annum) (Dawson & Hone 2012). This is similar to wild horse populations from around theworld (Garrott & Taylor 1990; Linklater et al. 2004; Grange et al. 2009; Scorolli & Lopez Cazorla 2010). <strong>The</strong>re isno data on the lifespan <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the Australian Alps, however studies <strong>of</strong> wild horses in Maryl<strong>and</strong>,United States <strong>of</strong> America (USA) found wild horses lived as long as 20 years (Kirkpatrick & Turner 2008).3.4 <strong>Wild</strong> horse social organisation <strong>and</strong> movement<strong>Wild</strong> horses live in small social units as harem or bachelor groups. Harem groups consist <strong>of</strong> a dominant male,multiple females <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>of</strong>f-spring (Menkhorst 1995). Bachelors are non-dominant males that have been6

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013forced out <strong>of</strong> <strong>their</strong> harems; they generally occur alone or in groups <strong>of</strong> two or three (Dobbie et al. 1993). <strong>The</strong>average group size (harem <strong>and</strong> bachelor groups) from three sites across the Australian Alps was 5.65 (± 0.51SE) (Walter & Hone 2003), while Drying (1990) found that harem group sizes in the Alpine region ranged fromtwo to 11 individuals, with groups typically consisting <strong>of</strong> one stallion, two mares <strong>and</strong> one foal. <strong>Wild</strong> horsesrarely have periods <strong>of</strong> social isolation during <strong>their</strong> lifetime except for bachelors in <strong>their</strong> pre-harem formationstage (van Dierendonck 2006). Harem groups tend to be stable breeding units <strong>and</strong> generally favour permanentlocations around reliable water sources (Dobbie et al. 1993). Within harem groups, adult mares form a longtermstable nucleus, while the breeding stallion is regularly replaced (van Dierendonck 2006). Bachelor groupsare more mobile <strong>and</strong> unstable (Dobbie et al. 1993).Groups <strong>of</strong> wild horses are loyal to undefended home ranges with central core use areas (Linklater 2000). <strong>The</strong>home ranges <strong>of</strong> groups overlap entirely with other groups <strong>and</strong> home range size increases with group size(Linklater 2000). Home ranges <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the Australian Alps have not been studied but there isinformation available from other environments. Home range sizes vary within a region <strong>and</strong> between regions. InQueensl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> central Australia wild horses were estimated to have a home range <strong>of</strong> approximately 100km²<strong>and</strong> 70km² respectively (Dobbie et al. 1993). In contrast, wild horses at Kiamanawa in New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, which hasa similar climate to the Australian Alps, had home ranges 0.96 to 17.7 km 2 (Linklater 2000). Given the climaticsimilarities, home range <strong>of</strong> horses in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps are likely to be similar to Kaimanawa.As prey animals in <strong>their</strong> native environment, a horse’s primary defence mechanism is rapid flight away fromthe threat <strong>of</strong> danger. It is therefore advantageous that they identify potential predators as quickly as possible(van Dierendonck 2006). This is aided by <strong>their</strong> monocular <strong>and</strong> binocular vision, which enables them to have anextensive view <strong>of</strong> <strong>their</strong> surrounds (Dobbie et al. 1993). With well developed hearing any movement is readilydetected (Dobbie et al. 1993).3.5 <strong>Wild</strong> horse habitat <strong>and</strong> diet preferences<strong>Wild</strong> horses occupy a range <strong>of</strong> habitats across Australia <strong>and</strong> the world. While they are best adapted to opengrassy plains they will also use rugged country (Norris & Low 2005). <strong>Wild</strong> horses are present from the highestto the lowest elevations in the Australian Alps (Walter 2002). Some groups may migrate to lower elevations inwinter but many horses maintain a high elevation (1600 metres) home range throughout winter (Dawson,unpublished data). Drying (1990) found that wild horses in Kosciuszko National Park (at a site in NSW sixkilometres from the <strong>Victoria</strong>n border) made extensive use <strong>of</strong> heaths <strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong>s for feeding, whilstavoiding the forests at all times <strong>of</strong> the year; this preference for open areas was broad-based with nodiscrimination between feeding <strong>and</strong> other activities. <strong>The</strong> preference for grassl<strong>and</strong>s over forest is universal forwild horses (Pratt et al. 1986; Keiper & Berger 1982; Berger 1986; Linklater et al. 2000). <strong>The</strong> only exceptionhas been observed in the middle <strong>of</strong> the day in summer when wild horses seek refuge from the heat <strong>and</strong>horseflies (Tabanidae) in forested areas (Duncan 1983; Dyring 1990; Keiper & Berger 1982; Berger 1986).<strong>Wild</strong> horses spend most (55-65%) <strong>of</strong> <strong>their</strong> time feeding (Duncan 1980). <strong>The</strong>y are generalist grazers with astrong preference for the greatest concentrations <strong>of</strong> high quality food (green plant matter); when green plantmatter becomes sparse, the horses’ tactic is to search out areas with the greatest concentrations <strong>of</strong> perennialherbaceous plants, green or dead (Duncan 1983). <strong>The</strong>ir diet mainly includes herbaceous plants (grasses, reeds,sedges <strong>and</strong> forbs), but they will also eat roots, bark, buds <strong>and</strong> fruit (Csurhes et al. 2009). Due to <strong>their</strong> forwardcutfront incisors they are able to graze close to the ground (Dobbie et al. 1993). <strong>Horses</strong> have a differentdigestive system to most ungulates (ho<strong>of</strong>ed mammals), which enables them to consume large quantities <strong>of</strong>low quality food <strong>and</strong> survive on a lower quality diet than cattle (Janis 2007). Cattle require time to chew <strong>their</strong>cud so cannot consume such large quantities but tend to select higher quality food (Janis 2007).<strong>Horses</strong> must drink at least once a day in summer <strong>and</strong> at least every second day during winter (Norris & Low2005). If food is plentiful horses will graze near water sources (Dobbie et al. 1993).7

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 20133.6 <strong>Wild</strong> horse mortality factorsWith few predators, unmanaged wild horse populations may increase in size <strong>and</strong> distribution until theyapproach carrying-capacity; at this point the population size stabilises as a result <strong>of</strong> a decrease in birth rates<strong>and</strong> survival rates caused by limited food availability (Grange et al. 2009; Scorolli & Lopez Cazorla 2010). Forexample, in the Camargue in France, Grange et al. (2009) found that a decrease in available food resources, asa result <strong>of</strong> increasing density, caused a loss <strong>of</strong> body condition <strong>and</strong> the survival <strong>of</strong> foals <strong>and</strong> adult femalesdecreased with increasing density.In sub-alpine <strong>and</strong> montane environments <strong>of</strong> the Australian Alps, there is evidence that between 1999 <strong>and</strong>2002, the growth <strong>of</strong> three wild horse populations was limited by food availability (Dawson & Hone 2012). <strong>The</strong>density <strong>of</strong> horses at the three sites was higher than the average determined from aerial surveys (see above).<strong>The</strong> Cowombat wild horse population had the highest density (6.4 km²), adult horses had the poorestcondition, recruitment (from birth to 3-years-old) was low, pasture biomass was low <strong>and</strong> population growthwas zero. In general however, unlike the Camargue example above, wild horses in the Australian Alps are notcontained <strong>and</strong> do not currently occupy <strong>their</strong> entire potential range (Dawson 2009). <strong>The</strong>refore there is scopefor the wild horse population to spread.It is not clear whether wild horse populations across the Australian Alps would reach ‘carrying capacity’because the ability to reach equilibrium density depends on the variability <strong>of</strong> environmental conditions. Instochastic environments characterised by a high degree <strong>of</strong> unpredictable environmental variance (e.g. rainfall),an equilibrium is not reached (McLeod 1997). <strong>The</strong>re are several examples <strong>of</strong> environmental events, inparticular drought, snow <strong>and</strong> fire, which have lead to dramatic declines in wild horse populations (thuspreventing the population from reaching carrying capacity). <strong>The</strong> eastern side <strong>of</strong> the AANPs (e.g. Buchan River,Lower Snowy, Suggan Buggan) lies in a rain-shadow <strong>and</strong> has limited available water. <strong>The</strong> drought in 1982-83was reported to have led to a dramatic decline <strong>of</strong> most wild horses in this area (Walter 2002), similar patternsare observed in central Australia (Dobbie et al. 1993). Drought can affect horses through thirst, starvation <strong>and</strong>ingestion <strong>of</strong> poisonous plants (Dobbie et al. 1993).At higher elevations wild horse mortality occurs as a result <strong>of</strong> severe snow events or long periods <strong>of</strong> snowcover in the alpine area (Walter 2002). In winter wild horses at higher elevations, such as those on the BogongHigh Plains, have to dig through snow to access food for many weeks <strong>of</strong> the year which leads to a loss <strong>of</strong> bodycondition in the horses (Dawson unpublished data). In some cases severe snow events have resulted inmortality <strong>and</strong> in one historic event in the Brindabella’s (Australian Capital Territory (ACT)) an entire populationwas wiped out (Walter 2002).<strong>The</strong> 2003 fires had a substantial impact on the wild horse population <strong>of</strong> the Australian Alps, with a sharpdecrease in the wild horse population size following the fires (Figure 2). After the fires, Walter (2003) indicatedthat when wild horse numbers were low, that there was great potential for the population to increasedramatically due to the increased availability <strong>of</strong> high quality food <strong>and</strong> reduced population pressure. This wasdemonstrated by the results <strong>of</strong> the 2009 aerial survey which showed that the population had increased by224% since 2003 (Dawson 2009a). In a slightly different context, Catling (1991) predicted that wild horseswould be advantaged by frequent low intensity fires due to a simplification in forest structure.Additional wild horse mortality factors that should be considered include wild dogs <strong>and</strong> parasitism. <strong>The</strong>re havebeen reports <strong>of</strong> wild dogs chasing foals in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps (Walter 2002). Parasitism <strong>and</strong> disease may also becauses <strong>of</strong> mortality <strong>and</strong>/or reduced health. However, neither <strong>of</strong> these factors has been formally investigated orquantified.8

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 20133. <strong>Wild</strong> horse environmental impacts3.1 <strong>Environmental</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horsesAustralia's ecosystems have evolved without the grazing pressure <strong>and</strong> the physical impact <strong>of</strong> heavy, hardho<strong>of</strong>edanimals (Carr & Turner 1959a; 1959b Ashton & Williams 1989; Green et al. 2006). <strong>Wild</strong> horse activity inthe <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps represents a type <strong>and</strong> intensity <strong>of</strong> impact to which native ecosystems <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> componentsare not adapted. <strong>The</strong> environmental impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses are recognised by <strong>Victoria</strong>’s environmentlegislation with “degradation <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> habitat caused by feral horses” listed as a threatening process underthe Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Guarantee Act (1988).<strong>The</strong> social <strong>and</strong> behavioural habits <strong>of</strong> wild horses as well as <strong>their</strong> physical characteristics (i.e. hard hooves, largesize, dietary preferences <strong>and</strong> general requirements), impact on the environment directly <strong>and</strong> indirectly.Trampling <strong>and</strong> grazing are the most researched <strong>and</strong> known agents <strong>of</strong> change associated with wild horses (Loydi& Zalba 2009). However, other negative actions include: consumption <strong>of</strong> native plants, bark chewing,compaction <strong>of</strong> soils, pugging (trampling <strong>of</strong> wet soils leaving a dense mat <strong>of</strong> deep footprints), track formation,wallowing (rolling), <strong>and</strong> the redistribution <strong>of</strong> nutrients <strong>and</strong> plant seeds via dung <strong>and</strong> urine. <strong>The</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong>these actions are summarised in Table 1.Table 1: Summary <strong>of</strong> wild horse environmental impactsElement Impacts Australian Alps research General researchSoil & substrate • Exposed soil surface;Dyring 1990Berman & Jarman 1998• soil loss & erosion;Whinam et al. 1994 Beever & Herrick 2006• down-slope sedimentation;De Stoppelaire et al. 2004• soil pugging, drying & compaction;Rogers 1991, 1994• loss <strong>of</strong> soil structural compositionTurner 1987especially on wet soils; &Loydi & Zalba 2009• creation <strong>of</strong> nutrient hotspots(especially nitrogen).Peatl<strong>and</strong>s (alsoknown as bogs ormossbeds)Waterways(streams &streambanks)Vegetation (&communities)• Drying out <strong>of</strong> bogs & potentialdraining <strong>of</strong> entire bog systems;• creation <strong>of</strong> bare pavements;• incision & soil erosion;• silt deposition downstream;• dominance <strong>of</strong> unpalatable species; &• loss <strong>of</strong> habitat for threatenedspecies.• Degradation <strong>of</strong> stream function;• incision & channelling;• soil compaction leading to decreasedinfiltration;• increased downslope sedimentation;• increased nutrient loads;• lateral erosion;• streambank disturbance & slumping;• fouling <strong>of</strong> waterholes; &• changes in water flow & drainagepatterns.• Removal <strong>of</strong> native vegetation cover;• dispersal <strong>of</strong> weed seeds;• changes to the vegetation structure& species composition <strong>of</strong> the groundstratum;• native tree mortality;• increase vulnerability <strong>of</strong> threatenedvegetation; &• increased nutrient loads.Dyring 1990Whinam & Chilcott 2002Whinam et al. 2003Tolsma 2008a, 2008bProber & Thiele 2007Dyring 1990Whinam & Comfort 1996Whinam & Chilcott 2002Prober & <strong>The</strong>ile 2007<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012Dyring 1990Whinam & Chilcott 2002Whinam & Comfort 1996Whinam et al. 1994Prober & <strong>The</strong>ile 2007Walter 2002McKay 2001Leigh et al. 1991Thomas 2010<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012Rogers 1991, 1994Beever & Brussard 2000Rogers 1991, 1994Beever & Brussard 2000Beever et al. 2003Beever et al. 2008Rogers 1991, 1994Turner 1987Loydi & Zalba 2009De Stoppelaire et al. 2004Bridle & Kirkpatrick 1999Cambell & Gibson 2001Schott 20029

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Native fauna • Competition for resources;• altered food availability;• habitat modification & loss;• increased vulnerability <strong>of</strong> threatenedspecies; &• competitive exclusion.Clemann et al. 2001Clemann 2002Brown et al. 2007Berman & Jarman 1998Lenehan 2010Zalba & Cossani 2009Beever & Herrick 2006Beever et al. 2008Nano et al 2003<strong>The</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> wild horse related degradation in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps will depend on:• wild horse density;• scale <strong>of</strong> activity (extent);• topography – including slope;• elevation;• climate;• recent weather;• local drainage;• access to suitable areas;• timing (i.e. seasonality <strong>of</strong> grazing);• the resilience <strong>of</strong> the vegetation community;• soil type (i.e. fineness <strong>and</strong>/or wetness);• the frequency <strong>and</strong> intensity <strong>of</strong> use;• effects <strong>of</strong> other sympatric species; <strong>and</strong>• the longer-term disturbance history <strong>of</strong> the site (Whinam etal. 1994; Beever et al. 2003; Beever et al. 2008).<strong>The</strong>se factors vary throughout the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps but some generalisations can be made.Concerns about the environmental impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses in the Australian Alps were first raised in the 1950s(Costin 1954). While there is extensive evidence <strong>of</strong> wild horse impacts in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, relatively fewstudies have been undertaken to quantify these impacts. Research includes:• Dyring (1990) conducted research on the effects <strong>of</strong> wild horses on sub-alpine <strong>and</strong> montaneenvironments in Australia. <strong>Wild</strong> horse impacts on soils, vegetation <strong>and</strong> streams were quantified infour small catchments in the southern Snowy Mountains. Seasonal habitat usage <strong>and</strong> the abundance<strong>of</strong> wild horses were also investigated. <strong>Wild</strong> horses were found to either initiate or perpetuate changesin sub-alpine <strong>and</strong> montane environments. Rates <strong>of</strong> environmental change could not however beinvestigated in the short time-frame <strong>of</strong> the study.• In 1999 an experimental program was established in the East Alps Unit <strong>of</strong> the ANP to determine theeffects <strong>of</strong> wild horse activity on grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> stream margins (Prober & Thiele 2007; <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>and</strong> Poll2012). Exclosure plots, that prevent horses from accessing a defined area but allow access for otheranimals, were established at Cowombat Flat <strong>and</strong> Native Cat Flat. Detailed vegetation monitoring <strong>of</strong>these exclosure plots, as well as monitoring <strong>of</strong> stream bank condition, disturbance <strong>and</strong> erosion wasundertaken in 1999, 2005 <strong>and</strong> 2012 (Prober & Thiele 2007; <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>and</strong> Poll 2012). <strong>The</strong> results show thatchanges to stream structure <strong>and</strong> function as a result <strong>of</strong> wild horses are clear <strong>and</strong> substantial, withsignificantly more incision <strong>and</strong> damage in the wild horse occupied area (outside the wild horseexclosures). Exclosure from horses has led to clear increases in vegetation height <strong>and</strong> increased littercover (<strong>Wild</strong> <strong>and</strong> Poll 2012). <strong>The</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> wild horses on vegetation structure <strong>and</strong> composition wasless consistent; however there was a trend for the recovery <strong>of</strong> dense swards <strong>of</strong> sedges <strong>and</strong> grassesassociated with the competitive exclusion <strong>of</strong> some lower stature species inside horse exclosures (<strong>Wild</strong><strong>and</strong> Poll 2012). In contrast, horse occupied areas tended to be characterised by low herbfield turfs,likely to be maintained by the preferential grazing <strong>of</strong> grasses <strong>and</strong> sedges by horses (ibid).• In 2008 Arn Tolsma from the Arthur Rylah Institute assessed the status <strong>and</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> 105 individualmossbeds (also commonly termed peatl<strong>and</strong>s or bogs) in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps (Tolsma 2008a; 2008b).This work supplemented broad-scale post-fire assessment <strong>of</strong> mossbeds that have been conducted bythe Arthur Rylah Institute since 2004. <strong>The</strong> aims included: to assess the current state <strong>of</strong> sub-alpinemossbed communities, estimate potential threats to mossbeds <strong>and</strong> determine restoration <strong>and</strong> othermanagement needs. Tolsma found that most systems show signs <strong>of</strong> contraction over a decadal scale,<strong>and</strong> few systems could be considered in relatively good condition. Evidence <strong>of</strong> wild horse activity10

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013(tracks, compaction, trampling, pugging <strong>and</strong> stream bank slumping) was observed in 67% (70 <strong>of</strong> 104)<strong>of</strong> the mossbeds assessed that year. Tolsma argued that on-going activity by wild horses is <strong>of</strong> greatconcern in the east Alps <strong>of</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong>. In the East Alps Unit <strong>of</strong> the ANP, 97% (63 <strong>of</strong> 65) <strong>of</strong> peatl<strong>and</strong>systems were found to be impacted (i.e. compacted, trampled or pugged) by wild horses (Tolsma2008b).• In 2011 the AALC commenced a project that aims to quantify the impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses on upl<strong>and</strong>streams <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s in the Australian Alps. <strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> this study will be available in autumn 2013<strong>and</strong> will provide further evidence <strong>of</strong> the impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses on sensitive environments.A number <strong>of</strong> protected areas regionally, nationally <strong>and</strong> internationally recognise that wild horses have anegative impact on the environment <strong>and</strong> have developed strategies to address these impacts (Table 2).Table 2: Examples <strong>of</strong> wild horse management plans <strong>and</strong> strategies <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> ecological rationaleRegion <strong>Wild</strong> horse strategy Rationale for the plan (ecological)AANPsNationalNewZeal<strong>and</strong>Kosciuszko National Park HorseManagement Plan.Namadgi National Park Feral horseManagement Plan.Guy Fawkes River National Park:Horse Management Plan.Feral horse Management Plan forOxley <strong>Wild</strong> Rivers National ParkProtecting the natural & culturalvalues <strong>of</strong> Carnavon National Park:A plan to manage wild horses &other pest animalsKaimanawa <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> Plan.<strong>The</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> & <strong>Wild</strong>life Service has legislative responsibility toprotect native habitats & wildlife within its reserves & a responsibilityto minimise the impact <strong>of</strong> introduced species, including wild horses.<strong>The</strong> 2006 Plan <strong>of</strong> Management called for a wild horse managementplan & the exclusion <strong>of</strong> wild horses from key areas. (NSW NPWS 2008).<strong>The</strong> plan aims to minimise the negative impact <strong>of</strong> wild horses includinggrazing on sensitive vegetation, trampling <strong>of</strong> streambanks, trailformation & erosion. <strong>The</strong>se can lead to draining <strong>of</strong> entire bog systems,loss <strong>of</strong> habitat for threatened species & silt deposition downstream.(ACT Government 2007).<strong>The</strong> National <strong>Parks</strong> & <strong>Wild</strong>life Service has legislative responsibility toprotect native habitats & wildlife within its reserves & a responsibilityto minimise the impact <strong>of</strong> introduced species, including wild horses(NSW NPWS 2006a). <strong>Wild</strong> horses are an introduced species that haveadverse impacts on Australian ecosystems with particularly severeconsequences for native fauna & flora (English 2001).<strong>Wild</strong> horses have been identified as posing a threat to the conservationvalues <strong>of</strong> the park & water quality. (NSW NPWS 2006b).Queensl<strong>and</strong> <strong>Parks</strong> & <strong>Wild</strong>life Service has a legal obligation to conserve& protect the natural values <strong>of</strong> Canarvon NP & control threateningprocesses caused by pest species including wild horses. Destructiveimpacts by wild horses have led to: the deterioration <strong>of</strong> aquaticecosystems & serious l<strong>and</strong>scape dysfunction (losses in biomass,accelerated erosion, soil compaction, altered species composition &vegetation structure & altered fire ecology). (Weaver 2007).<strong>Horses</strong> have been shown to adversely affect nationally significantecological values. <strong>The</strong>re is a need to eliminate the impacts <strong>of</strong> horses onimportant conservation values. (DOC 2006).In addition to these wild horse plans <strong>and</strong> strategies, a series <strong>of</strong> workshops on wild horse impact <strong>and</strong>management in the Australian Alps (see: Walters & Hallam 1993; O’Brien & Solomon 2004) <strong>and</strong> a nationalworkshop (see: Dawson et al. 2006) have demonstrated widespread concern from scientists <strong>and</strong> practitionersabout the impacts <strong>of</strong> wild horses in alpine <strong>and</strong> sub-alpine environments.<strong>The</strong> impacts that wild horses have on the soils <strong>and</strong> substrate, peatl<strong>and</strong>s , waterways, vegetation <strong>and</strong> fauna <strong>of</strong>the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps is considered below in greater detail.3.2 Impacts on soil <strong>and</strong> substrateIt is generally accepted that alpine areas are more susceptible to damage by hard hooved animals such as wildhorses than most other environments, due to <strong>their</strong> wet fragile soils <strong>and</strong> slow vegetation growth rates (Whinamet al. 1994). <strong>Wild</strong> horse trampling <strong>and</strong> grazing can lead to major changes to the soil, including: pugging, drying,11

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013compaction <strong>and</strong> erosion (Berman & Jarman 1988; Dyring 1990; Beever & Herrick 2006; De Stoppelaire et al.2004).Some <strong>of</strong> the immediate effects <strong>of</strong> wild horses include the creation <strong>of</strong> tracks <strong>and</strong> bare patches due to trampling,wallowing <strong>and</strong> horse camps (see Photo 1, 2 <strong>and</strong> 3). Trampling <strong>and</strong> wallowing have been found to causelocalised damage by reducing organic matter <strong>and</strong> exposing <strong>and</strong> compacting the soil surface (Dyring 1990).Track networks are formed by the movement <strong>of</strong> wild horses. Dyring (1990) found that wild horses produceextensive track networks in the Australian Alps. Continual trampling by wild horses can increase soilcompaction <strong>and</strong> therefore reduce aeration <strong>and</strong> pore space <strong>of</strong> soils <strong>and</strong> subsequently decrease waterinfiltration <strong>and</strong> moisture content <strong>of</strong> soils. In addition, trampling <strong>and</strong> wallowing reduce plant cover <strong>and</strong> diversity(Dyring 1990). <strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> vegetation cover means a reduction in shading for soils <strong>and</strong> less organic matterinputs, resulting in greater erosion <strong>and</strong> a reduced ability <strong>of</strong> the soil to retain moisture (Beever & Herrick 2006).Beever <strong>and</strong> Herrick (2006) found in western Great Basin sites (USA), three to 15 times lower penetrationresistance (a measure <strong>of</strong> soil compaction) in the soil surfaces <strong>of</strong> sites without wild horses (compared to thosewith wild horses).Photo 1: Trampled area at Cowombat Flat (source: Arn Tolsma 2008).Photo 2: <strong>Wild</strong> horse camp, Davies Plain (Source: Arn Tolsma 2008)12

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Photo 3: Trampling at <strong>The</strong> Playgrounds, ANP (Source: Arn Tolsma 2008)In the Australian Alps wild horse tracks have been found to result in a loss <strong>of</strong> plant cover, erosion (averagingbetween 40-156cm³/m²), soil compaction, <strong>and</strong> a loss <strong>of</strong> soil structural composition (Dyring 1990). Drying(1990) found that the soil on tracks was significantly compacted compared with <strong>of</strong>f-track areas. Compactionwas found to be most severe on dry soils, where 20-50 passes by wild horses resulted in significantlycompacted soils. Compaction was found not to increase substantially with subsequent passes. <strong>The</strong>refore anaverage group <strong>of</strong> four wild horses using a new track twice daily for less than a week will result in significantcompaction. <strong>Wild</strong> horses were found to have similar usage <strong>of</strong> sub-alpine <strong>and</strong> montane areas, with nodifference in compaction or track width demonstrated between these sites (Dyring 1990). Whinam et al.(1994) in <strong>their</strong> study <strong>of</strong> horse riding in Tasmanian Alpine environments found that 20-30 passes by horses hassubstantial immediate as well as delayed effects on the soils <strong>of</strong> shrubl<strong>and</strong>, herbfield <strong>and</strong> bolster heathcommunities, however effects on dry grassl<strong>and</strong> soils were less evident. <strong>Wild</strong> horse exclosure experiments inthe eastern <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps have shown that continued grazing <strong>and</strong> trampling by wild horses has maintained lowherbfield turfs, where the soil surface is more susceptible to trampling impacts than the grassl<strong>and</strong>s found inthe horse exclosure plots (<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012; Whinam et al. 1994).Dyring (1990) found that wet soils were less prone to compaction but more susceptible to structural damagethan dry soils. This is supported by Rogers (1994) who demonstrated that dry areas are more resistant t<strong>of</strong>racturing than wet areas, which were more easily broken up by trampling. <strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> soil structuralcomposition is most pronounced on wet soils because horse trampling <strong>and</strong> grazing fractures saturated soils(Rogers 1994; Turner 1987; Dyring 1990). Fracturing <strong>of</strong> water saturated grassl<strong>and</strong> can result in downslopesedimentation, water ponding, <strong>and</strong> opportunities for the establishment <strong>of</strong> weeds (Rogers 1994). <strong>The</strong> gradient<strong>of</strong> the slope has been found in other studies to directly correspond to the level <strong>of</strong> erosion. <strong>The</strong> steeper theslope the more prone it will be to erosion (Dyring 1990).Disturbances to the substrate caused by actions such as wild horse trampling, wallowing <strong>and</strong> grazing increasethe exposure <strong>of</strong> soils to the elements (such as wind, rain <strong>and</strong> needle ice), leads to the removal <strong>of</strong> vegetation<strong>and</strong> alters drainage conditions hence increasing susceptibility to erosion (Dyring 1990). In central Australia,wild horses were linked to aggravated gully erosion in areas close to water (Berman & Jarman 1988). <strong>Wild</strong>horses caused considerable erosion in a s<strong>and</strong>y environment in the USA: over a five to seven year period fencedplots (excluding horses) were on average 0.63 m higher than unfenced plots in s<strong>and</strong> dunes habitats (DeStoppelaire et al. 2004).Pugging <strong>of</strong> soil (trampling <strong>of</strong> wet soils leaving a dense mat <strong>of</strong> deep footprints), in particular around wetl<strong>and</strong>s<strong>and</strong> waterways, can change soil nutrient status, <strong>and</strong> increase water turbidity <strong>and</strong> sediment loads in adjacentwaterways (O’Connor 2005). Dyring (1990) found that wild horses in the Australian Alps can create nutrient13

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013hotspots due to the high levels <strong>of</strong> nutrients (especially nitrogen) in <strong>their</strong> dung <strong>and</strong> urine. Manure in dung pilesincreases the availability <strong>of</strong> soil nutrients, especially nitrogen <strong>and</strong> phosphorous, thus creating microhabitatssuitable for weed invasion (Loydi & Zalba 2009).3.3 Impacts on vegetation<strong>The</strong> level <strong>of</strong> impact wild horses have on native vegetation is dependent on the amount <strong>and</strong> type <strong>of</strong> use, <strong>and</strong>,the resilience <strong>of</strong> the vegetation (Whinam et al. 1994). <strong>The</strong> most obvious impact wild horses have on vegetationis a reduction in vegetation cover <strong>and</strong> height, however they may also alter plant species composition, richness<strong>and</strong> diversity, <strong>and</strong> contribute to weed invasion (Turner 1987; Dyring 1990; Rogers 1991; Beever & Brussard2000; De Stoppelaire et al. 2004; Loydi & Zalba 2008; <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>and</strong> Poll 2012). Trampling by wild horses also altersvegetation, particularly along tracks <strong>and</strong> at watering points (Turner 1987; Dyring 1990; Rogers 1991; Beever &Brussard 2000).3.3.1 Removal <strong>of</strong> native vegetation by grazing, trampling <strong>and</strong> wallowingVertebrate grazers can negatively affect the cover <strong>of</strong> herbs in alpine <strong>and</strong> subalpine regions <strong>of</strong> Australia (Bridle& Kirkpatrick 2001). Dyring (1990) found that wild horses preferentially graze grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> healthl<strong>and</strong>s.Studies in the greater alpine region have demonstrated that a decrease in grazing pressure from introducedherbivores has led to an increase in plant cover or flower stem production (Carr & Turner 1959a; 1959b;Wimbush & Costin 1979a; 1979b; 1979c; Leigh et al. 1991; Wahren et al. 1994). Bridle <strong>and</strong> Kirkpatrick (2001) in<strong>their</strong> study <strong>of</strong> Tasmanian alpine <strong>and</strong> subalpine plains found the impacts <strong>of</strong> domestic stock (i.e. cows, horses,sheep), rabbits <strong>and</strong> native herbivores on treeless subalpine vegetation were much greater than the effects <strong>of</strong>natives herbivores <strong>and</strong> rabbits alone (Bridle & Kirkpatrick 1999).McKay (2001) conducted a survey <strong>of</strong> the impacts <strong>of</strong> horse-riding <strong>and</strong> walking on the alpine vegetation <strong>of</strong>Mount Bogong. Trampling was found to reduce the height, cover <strong>and</strong> abundance <strong>of</strong> both shrub <strong>and</strong> groundflora within track areas <strong>and</strong> to result in greater exposure <strong>of</strong> bare ground. Beever et al. (2008) argue that theloss <strong>of</strong> connectivity in shrub canopy due to rubbing <strong>and</strong> trampling may increase rates <strong>of</strong> isolation,evapotranspiration <strong>and</strong> soil loss at small spatial scales.Results from the Cowombat Flat <strong>and</strong> Native Cat Flat horse exclosure plot monitoring program have shown thathorse trampling <strong>and</strong> grazing has resulted in the removal <strong>of</strong> vegetation <strong>and</strong> increased bare ground in horseoccupied areas (<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012). In contrast, fenced horse exclosure plots showed a trend for increasingvegetation cover <strong>and</strong> decreasing bare ground as they recovered from past horse disturbance over a thirteenyear period (ibid).It is argued that grazing may have an impact on the reproductive success <strong>of</strong> some flora species by impacting onthe dispersal opportunities <strong>of</strong> wind-dispersed species as well as <strong>their</strong> ability to attract pollinators; both <strong>of</strong>these functions are affected by flower height (Bridle & Kirkpatrick 1999). For example, on the AssateagueBarrier Isl<strong>and</strong> (USA), a small herbaceous annual, Amaranthus pumilus was once abundant <strong>and</strong> is now limited toa couple <strong>of</strong> individuals; its decline is linked to wild horse grazing <strong>and</strong> trampling (De Stoppelaire et al. 2004).Bridle <strong>and</strong> Kirkpatrick (1999) found decreased fecundity <strong>of</strong> herbs with increasing grazing pressures. InAustralia, clipping experiments on alpine herbs have shown that flowering success may be retarded if plantsare clipped early in the growing season or if they are cut more than once (Leigh et al. 1991).3.3.2 Change in vegetation composition <strong>and</strong> structureGrazing by introduced herbivores can alter the appearance, productivity <strong>and</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> vegetationcommunities (Dyring 1990; Hobbs & Hyeneke 1992). This may be due to reduced regeneration/recruitment asa direct result <strong>of</strong> selective grazing or the physical impacts <strong>of</strong> trampling <strong>and</strong> erosion. <strong>Wild</strong> horses selectivelygraze palatable species <strong>and</strong> have the potential to change the composition <strong>of</strong> threatened vegetation14

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013communities (Dyring 1990). Redistribution <strong>of</strong> nutrients through dung can also contribute to the changes invegetation patterns (Dyring 1990).Trampling can create openings in vegetation that provide opportunities for new plants to become established.Different vegetation types demonstrate differing levels <strong>of</strong> resistance (tolerance) to trampling. Within some,non-tolerant vegetation types, trampling can slow the growth <strong>of</strong> dominant species sufficiently to allow thepersistence <strong>of</strong> less vigorous species (Hobbs & Hyeneke 1992).Dyring (1990) found trampled sites (<strong>and</strong> areas adjacent to track systems) had lower native plant diversity <strong>and</strong> ahigher abundance <strong>of</strong> exotic species. Plants found on wild horse tracks were characteristically non-woodyprostrate fast-growing annuals <strong>and</strong> grasses, with hemicryptophitic life-forms (species with renewal buds nearthe surface), which tolerated trampling better than upright plants (Dyring 1990). Similarly, horse occupied sitesat Cowombat Flat <strong>and</strong> Native Cat Flat exhibited a predominance <strong>of</strong> hemicryptophitic species in contrast tohorse exclosure plots, which were dominated by grasses <strong>and</strong> sedges (<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012). Grassl<strong>and</strong>s are moreresilient to the impact <strong>of</strong> wild horses than other communities where ferns, mosses <strong>and</strong> shrubs are importantcomponents <strong>of</strong> the vegetation (Whinam et al. 1994; Venn et al. 2009). Whinam <strong>and</strong> Chilott (1999) found thatshrubs <strong>and</strong> shrubl<strong>and</strong> communities were more vulnerable to trampling than other life-forms or vegetationtypes in central Tasmanian alpine vegetation.As well as affecting vegetation community composition, wild horse activity can affect the physical structure <strong>of</strong>vegetation communities. Exclosure experiments have shown that vegetation cover <strong>and</strong> height is far greater inhorse free sites (Turner 1987; Beever & Brussard 2000; De Stoppelaire et al. 2004; Prober & <strong>The</strong>ile 2007; <strong>Wild</strong>& Poll 2012). Lower plant biomass was found in the Australian Alps where wild horse densities were higher(Walter 2002). In the Cowombat Flat <strong>and</strong> Native Cat Flat wild horse exclosure plot monitoring program, thefollowing results occurred in the wild horse exclosures (see also Photo 4):• a significant increase in the average height <strong>of</strong> vegetation;• a significant increase in litter cover;• no significant effect in species richness at Cowombat Flat;• significantly lower native species richness at Native Cat Flat, due to the gradual competitive exclusion<strong>of</strong> some lower stature species by dense swords <strong>of</strong> sedges <strong>and</strong> grasses;• no indication <strong>of</strong> an increase in weed richness/abundance due to exclosure (Prober & <strong>The</strong>ile 2007,<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012).While the effect <strong>of</strong> wild horses on vegetation structure <strong>and</strong> composition was less consistent than the effect <strong>of</strong>horses on vegetation height, plots inside horse exclosures were <strong>of</strong>ten characterised by dense swards <strong>of</strong> sedges<strong>and</strong> grasses associated with the competitive exclusion <strong>of</strong> some lower stature species (<strong>Wild</strong> & Poll 2012). Incontrast, horse occupied areas tended to be characterised by low herbfield turfs, likely to be maintained bythe preferential grazing <strong>of</strong> grasses <strong>and</strong> sedges by horses (ibid). <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>and</strong> Poll (2012) suggest that theresurgence <strong>of</strong> dense sedges <strong>and</strong> grasses <strong>and</strong> competitive exclusion <strong>of</strong> some lower stature species may indicaterestoration to a previous, more natural state <strong>and</strong> possibly towards a peatl<strong>and</strong> environment.Studies in the USA have shown that wild horses can lower vegetation cover, abundance <strong>and</strong> flora speciesrichness as well as alter the species composition <strong>and</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> the vegetation (by increasing thepredominance <strong>of</strong> grazing resistant forbs <strong>and</strong> exotic plants <strong>and</strong> creating a less continuous shrub canopy)(Beever et al. 2003; Beever <strong>and</strong> Herrick 2006; Stoppelaire et al. 2004; Beever & Brussard 2000). Using a series<strong>of</strong> monitoring <strong>and</strong> exclosure plots in the Kaimanawa Mountains, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, Rogers (1991; 1994), found thatwild horses severely disrupted the composition <strong>of</strong> the native vegetation. In the grazed plots, species biomass<strong>and</strong> stature was low for all potentially taller, palatable grasses (Rogers 1991).15

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013Photo 4: Cowombat Flat wild horse exclusion plots from the air (source: Ge<strong>of</strong>f Robinson).3.3.3 Threatened vegetationIn the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, wild horses are considered to be one <strong>of</strong> the major threats to alpine ecosystems (Tolsma2008b). <strong>Wild</strong> horses are considered to be a serious threat to at least five plant communities listed in the<strong>Victoria</strong>n Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG) (Appendix 1), <strong>and</strong> numerous plant species (Appendix 2).<strong>The</strong> threat that wild horses pose to threatened species <strong>and</strong> communities is recognised in the listing <strong>of</strong>“degradation <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> habitats caused by wild horses” as a potentially threatening process under the FFGAct. It is likely that wild horses threaten many other species or communities not yet identified or investigated.Trampling by ungulates (ho<strong>of</strong>ed animals) has been considered one <strong>of</strong> the major threats to several FFG listedalpine vegetation communities. Within the Caltha introloba Herbl<strong>and</strong> Community, cushions <strong>of</strong> tuft-rush(Oreobolus), which play an important role in reducing the erosive forces <strong>of</strong> flowing water, may be dislodged bytrampling, or <strong>their</strong> regeneration disrupted (McDougall 1982; McDougall & Walsh 2007). Similarly, the AlpineSnowpatch Community, situated on steep sheltered slopes, is subject to constant irrigation during the thawwhich renders them particularly susceptible to soil loss following damage to the vegetation by trampling(McDougall 1982; Wahren et al. 2001a; McDougall & Walsh 2007). Montane Swamp, because <strong>of</strong> its position inthe l<strong>and</strong>scape, is another listed community likely to be susceptible to the impact <strong>of</strong> wild horses (Dawson 2009).Ecological communities which have been listed under the Federal Environment Protection <strong>and</strong> BiodiversityConservation Act 1999 (EPBC) <strong>and</strong>/or the <strong>Victoria</strong>n FFG Act 1988, <strong>and</strong> that are potentially at risk from wildhorses, are presented in Appendix 2.In order to mitigate the threat that wild horses pose to threatened flora species in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, <strong>Parks</strong><strong>Victoria</strong> has established three wild horse exclusion fences around particularly threatened <strong>and</strong> sensitive16

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wild</strong> <strong>Horses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Impact in the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps May 2013communities. In 2002 two wild horse exclusion fences were established on Davies Plain around sub-alpinebogs known to contain several threatened plant species <strong>and</strong> the threatened Alpine Water Skink. In 2010 anexclusion fence was established at <strong>The</strong> Playgrounds to protect a population <strong>of</strong> threatened Marsh Leek Orchid(Prasophyllum niphopedium) (see Photo 5). <strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> all exclusion fences is to protect these species (<strong>and</strong> <strong>their</strong>habitat in the case <strong>of</strong> the Alpine Water Skink) from trampling <strong>and</strong> grazing by wild horses.Photo 5: <strong>The</strong> Playgrounds wild horse exclusion fence, established to protect a population <strong>of</strong> threatened Marsh Leek Orchid,an alpine bog community <strong>and</strong> habitat for the endangered Alpine Water Skink (source: <strong>Parks</strong> <strong>Victoria</strong> 2012).3.3.4 Weed dispersal <strong>and</strong> encouragement<strong>Wild</strong> horses can facilitate weed invasion through dispersal <strong>and</strong> the creation <strong>of</strong> a favourable environment forweeds through disturbance. Weed species are dispersed through attachment to the body <strong>of</strong> the wild horse(epizoochory) or by being ingested <strong>and</strong> later excreted (endozoochory) (Cambell & Gibson 2001). <strong>The</strong>reforewild horses have the potential to disperse weeds both long <strong>and</strong> short distances <strong>and</strong> can subsequentlycontribute to the establishment <strong>of</strong> weed species across several spatial scales (Nimmo & Miller 2007). Weaver<strong>and</strong> Adams (1996) argue that within <strong>their</strong> home range, horses are a potentially significant vector in thedispersal <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> weed species.While wild horses are less likely than domestic horses (i.e. recreational riding horses or horses illegally releasedinto the region) to introduce new weeds into the <strong>Victoria</strong>n Alps, there is potential for this to occur, especiallyconsidering <strong>their</strong> increasing range <strong>and</strong> the potential for wild horses to occur across tenures (i.e. farms, stateforests <strong>and</strong> national park). Many species <strong>of</strong> seed are transported in the dung <strong>of</strong> wild horses. Dung can be asource <strong>of</strong> viable seed taxa not otherwise found in a community (Campbell & Gibson 2001). Campbell <strong>and</strong>Gibson (2001) found that horses pass large numbers <strong>of</strong> seeds through <strong>their</strong> digestive tract generally within48hours <strong>of</strong> consumption (but sometimes longer), <strong>and</strong> many <strong>of</strong> these seeds remain viable (Weaver & Adams1996). In some cases the process <strong>of</strong> digestion scarifies the seed coat, enhancing germination (Campbell &Gibson 2001). Weaver <strong>and</strong> Adams (1996) investigated the spread <strong>of</strong> environmental weeds into areas <strong>of</strong> nativevegetation along horse-riding tracks in three national parks in <strong>Victoria</strong> (including the ANP). Twenty-ninespecies <strong>of</strong> weeds were found to be dispersed via horse manure.<strong>Wild</strong> horse disturbance (i.e. dung, soil disturbance <strong>and</strong> pugging) can provide favourable environmentalconditions for the germination <strong>and</strong> colonisation <strong>of</strong> weed species (Dyring 1990; Rogers 1991; Loydi & Zalba2009). <strong>Wild</strong> horse dung can result in significant changes in vegetation <strong>and</strong> can introduce <strong>and</strong> encourage someinvasive weed species that could eventually colonise more pristine areas (Loydi & Zalba 2009). Nutrients indung can favour weed establishment, with weeds establishing more vigorously in areas both trampled <strong>and</strong>subject to deposition <strong>of</strong> dung. In a study <strong>of</strong> the potential for horse dung to act as an invasion window inmontane pampas grassl<strong>and</strong>s, Loydi <strong>and</strong> Zalba (2009) found that the cover <strong>of</strong> introduced species was higher indung piles than in control plots. Dyring (1990) speculated that the redistribution <strong>of</strong> nutrients through uneven17