PED guidebook main sxn rev6. FINAL.pdf - LGRC DILG 10

PED guidebook main sxn rev6. FINAL.pdf - LGRC DILG 10

PED guidebook main sxn rev6. FINAL.pdf - LGRC DILG 10

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

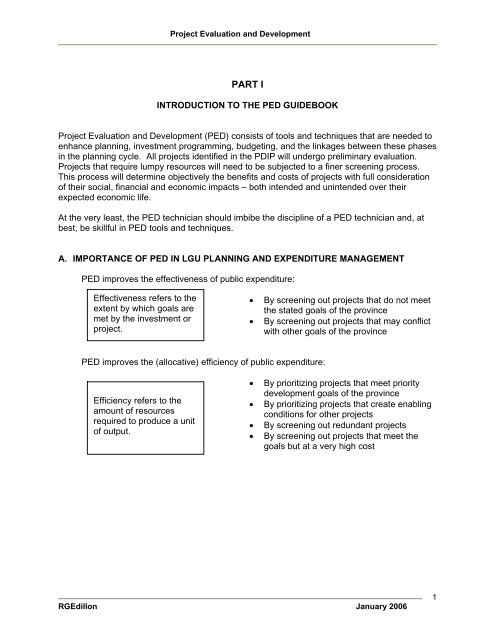

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentPART IINTRODUCTION TO THE <strong>PED</strong> GUIDEBOOKProject Evaluation and Development (<strong>PED</strong>) consists of tools and techniques that are needed toenhance planning, investment programming, budgeting, and the linkages between these phasesin the planning cycle. All projects identified in the PDIP will undergo preliminary evaluation.Projects that require lumpy resources will need to be subjected to a finer screening process.This process will determine objectively the benefits and costs of projects with full considerationof their social, financial and economic impacts – both intended and unintended over theirexpected economic life.At the very least, the <strong>PED</strong> technician should imbibe the discipline of a <strong>PED</strong> technician and, atbest, be skillful in <strong>PED</strong> tools and techniques.A. IMPORTANCE OF <strong>PED</strong> IN LGU PLANNING AND EXPENDITURE MANAGEMENT<strong>PED</strong> improves the effectiveness of public expenditure:Effectiveness refers to theextent by which goals aremet by the investment orproject.• By screening out projects that do not meetthe stated goals of the province• By screening out projects that may conflictwith other goals of the province<strong>PED</strong> improves the (allocative) efficiency of public expenditure:Efficiency refers to theamount of resourcesrequired to produce a unitof output.• By prioritizing projects that meet prioritydevelopment goals of the province• By prioritizing projects that create enablingconditions for other projects• By screening out redundant projects• By screening out projects that meet thegoals but at a very high costRGEdillon January 20061

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentB. <strong>PED</strong> AND THE OVERALL PLANNING CYCLEPDP PDIP AIPProjects forLocal fundingProjects forexternal fundingSmall ProjectsBig ProjectsPreliminaryEvaluationPreliminaryEvaluationPreliminaryEvaluationComplete <strong>PED</strong>Complete <strong>PED</strong>Covered in <strong>PED</strong> GuidebookProjectproposalProject evaluation takes off from the provincial plan, the multi-year investment plan and theannual investment plan. Projects will first be classified according to funding source. All projectswill undergo the preliminary evaluation. The complete <strong>PED</strong>, however, will be limited to only thebig projects and those that will be proposed for external funding. Essentially, the complete <strong>PED</strong>is concerned with the finer screening of projects. In the next part, we suggest a scheme toclassify projects into “big” or “small”.The next stage is to specify the plans for the efficient implementation of projects that passed theproject evaluation stage. This includes specifying, in detail, arrangements for implementationand the subsequent operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance of the project. Many of the steps undertakenin the project evaluation will be used in this stage.For projects that is proposed for external funding, a full blown project proposal will bedeveloped.RGEdillon January 20062

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentC. PLAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKThis <strong>guidebook</strong> explains in detail what we mean by “discipline of a <strong>PED</strong> technician” anddiscusses the <strong>PED</strong> tools and techniques.There are two major sections in this guideline - Project Evaluation and Development(<strong>PED</strong>), and Project Proposal Development. A Technical Appendix on <strong>PED</strong> is included.This contains the more detailed and technical discussion on the principles and conceptsbehind <strong>PED</strong>. This is a recommended reading for everyone who is interested inconducting serious <strong>PED</strong>.RGEdillon January 20063

Project Evaluation and Development1.2.2 impact evaluation - where the interest is on the outcome and impact of theproject on the intended beneficiary and societyWith respect to the planning phase, the usage of Project Evaluation is more akin to exanteevaluation. This is also sometimes called the feasibility study.2. Feasibility study pertains to the whole gamut of analyses carried out to determine if theproject can be implemented and achieve the desired goals. It includes market analysis,technical, financial, and economic analyses, assessment of environmental and marketrisks and institutional analysis. These components of a feasibility study are explained inthe next section.3. Pre-feasibility study is similar to the feasibility study in terms of the principles and stepsfollowed. The difference lies in the depth and, therefore, accuracy of the analysis. Thisis largely due to the short duration of time allowed for the conduct of the pre-feasibilitystudy. Usually, the purpose of a pre-feasibility study is to determine if a more in-depthfeasibility study is warranted.4. Project appraisal is similar to the feasibility study in terms of the steps followed.Oftentimes, however, the parties responsible for financing the project are the ones thatconduct the appraisal. This, being the case, the interest is in verifying the assumptionsused in the earlier feasibility study.5. Economic life refers to the time span over which the project is able to generate benefits(or earnings) and influence development or economic behavior. This is determined bythe rate of depreciation subject to operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance schemes, andobsolescence when new (and better) technologies become available.6. Discount rate reflects the opportunity cost of money. The concept is based on thepremise that money received now is more valuable compared to money to be receivedat some time in the future. Its value depends on the alternative defined. The next twodefinitions illustrate this concept.The discount rate 1 is equal to the interest charged on a loan but deducted in advance. IfP is the amount of the principal, r is the interest rate, and the repayment period is just 1year, thenAmount in year 1 is P (1 + r)If the interest is deducted in advance, the amount to be given to the borrower atyear 0 is:P= +dP 1 r7. Financial rate of discount is applied when the resources devoted to the project are seento compete with private investments. Usually, this is pegged at the commercial lendingrate. In other words, the resources to be spent for the project is compared againstprojects that can be undertaken by the private sector and earn an average rate of return.1 Note that the terms “discount rate” and “rate of discount” are used interchangeably.RGEdillon January 20065

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentExample (a): Supposed your friend wants to borrow from you the amount of P 150,000with a promise to be paid back after 1 year. Will you be satisfied with a repayment ofexactly P 150,000?The answer is most likely a “no”. If you are a businessman, you could have invested itsomewhere profitable and earned an interest of 20%. With this in mind, you can lendthe amount of P 125,000 now and agree to accept payment of P 150,000 a year fromnow.8. Social rate of discount or social rate of time preference reflects the opportunity cost ofmoney as valued by society as a whole, and not just by the finance sector. It is the rateat which an individual would be willing to give up current consumption. In other words,the resources devoted to the project are seen to compete with private consumption.Usually, this is pegged at the interest rate paid on long-term government bonds. 2Example (b): Let us modify the premise of example (a). Suppose you are not abusinessman and are unlikely to undertake investments. The alternative for you is toplace the money in a bank where it will earn the savings rate. Even better, you canpurchase government bonds with maturity of 1 year. If this latter promises an interestearning of 7%, then you can allow your friend to borrow P 140,186.91 now in exchangefor the promised repayment of P 150,000 a year from now.150,000140,186.91=1.079. Market price vs. Economic price.9.1 Market price is the price at which the good or service is being bought and sold at theend-users’ market (as opposed to farmgate). We also sometimes refer to this asfinancial price.9.2 Economic price reflects the value that society places on the good or service withdue consideration for its scarcity and relative importance, absent market distortions.For instance, there is consideration as to whether the inputs are sourceddomestically or imported, or whether the outputs are marketed only within thecountry or are exported, etc. If they are traded in the international market, thenprocuring them (in the case of project inputs) or supplying them (in the case ofproject outputs) will affect the country’s foreign exchange situation.Example (c): The cost of one kilo of fresh tomatoes, when sold in the farm inBulacan is only P20. When sold in the wet market in Cubao is P50. Assuming thatthe tomatoes come from Bulacan, this means that only P20 will be received by thetomato farmer and the difference goes to the trade and transport cost. The marketprice, in this case, in Cubao is P50 but the economic price is only P20.2 The NEDA Public and Investment Staff estimates the social rate of discount. Sometimes, funders have their ownvalues of the social rate of discount. It is suggested that both be consulted by the PROJECT EVALUATIONanalyst.RGEdillon January 20066

Project Evaluation and Development<strong>10</strong>. Shadow prices. The more popular term for economic price is shadow price. It is basedon the same principle that the true price reflects the relative scarcity of the good insociety. In particular, the NEDA estimates the values of the shadow discount rate(SDR), reflecting the true opportunity cost of money, the shadow exchange rate (SER)reflecting the true opportunity cost of foreign currency and the shadow wage rate (SWR)reflecting the true opportunity cost of labor. Presently, the shadow discount rate isestimate to be 15%, the shadow exchange rate is 20% more than the official exchangerate and the shadow wage rate of unskilled labor 3 at only 60% of the current wage rate. 411. Present value is the value now of future incomes and costs. It is computed by applyingthe appropriate discount rate that reflects the opportunity cost of money. The formula isgiven below, where PV t is the present value of the amount X in year t and r is thediscount rate.XtPVt= (1+ r)tExample (c): A project is expected to generate revenues beginning year 2 until year 5.Every year the revenue amounts to P <strong>10</strong>0,000.00. We are interested to know thepresent value of this revenue stream (that is, at year 0). Assume a discount rate of 15%.Year UndiscountedamountFormula0 01 0<strong>10</strong>0,0002 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 2(1 + 0.15)<strong>10</strong>0,0003 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 3(1 + 0.15)<strong>10</strong>0,0004 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 4(1 + 0.15)<strong>10</strong>0,0005 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 5(1 + 0.15)Discountedamount75,614.3765,751.6257,175.3249,717.67TOTAL 400,000.00 248,258.993 There is no official definition that distinguishes skilled from unskilled labor. A skilled worker may derive hisskills from professional or technical education, or acquired on the job. In practice, we consider a skilled worker asone who bring expertise to the performance of a given job.4 The values of the SDR, SER and SWR may change from time to time. Therefore, the <strong>PED</strong> analyst is advised toverify the values with the NEDA-PIS.RGEdillon January 20067

Project Evaluation and Development12. Net present value (NPV). The stream of benefits and costs can be expressed in presentvalue terms. The net present value (NPV) is the difference between the present value ofbenefits and the present value of costs.B CtNPV = −t(1+ r) (1+r)TTt∑ t ∑t= 0 t=0where B t and C t are the benefits and costs accruing at time t, respectively.The decision rule is to reject a project thatyields a negative NPV.YearExample (d) : Consider the previous example (c). Let us assume that the projectentails an investment cost of P 150,000 and all these are spent on year 0.Undiscountedamount0 150,000 01Cost Revenues Revenuesless CostFormula Discounted Undiscounted Formula Discountedamount amountamount150,000(1 + 0.15)150,000 (150,000)2 <strong>10</strong>0,000<strong>10</strong>0,0002(1 + 0.15)3 <strong>10</strong>0,000<strong>10</strong>0,0003(1 + 0.15)4 <strong>10</strong>0,000<strong>10</strong>0,0004(1 + 0.15)5 <strong>10</strong>0,000<strong>10</strong>0,0005(1 + 0.15)75,614.37 75,614.3765,751.62 65,751.6257,175.32 57,175.3249,717.67 49,717.67T O T A L 248,258.99 98,258.99The net present value (NPV) is computed to be P 98,258.99. Since the NPV is positive,we conclude that the project is viable.13. Rate of return, or financial rate of return, is the ratio of the earnings from the asset to thevalue of that asset. For public projects, we normally do not compute for the financial rateof return since these are not expected to yield profits.14. Internal rate of return (IRR) is the discount rate at which the net present value is zero.RGEdillon January 20068

Project Evaluation and Development⎛ B C ⎞− ⎟=0t⎝(1 r) (1 r) ⎠∑ T t t⎜ tt=0 + +where B t is the value of benefits at time t and C t is the value of costs at time t. Theproject life is T years.15. Economic internal rate of return (EIRR) is similarly defined as the IRR except that thebenefits and costs are expressed in economic prices.The decision rule is to reject a project that yields anEIRR that is less than the social rate of discount.16. Benefit-cost ratio (BCR) is simply the ratio of the total benefits to total cost. Discountingis applied when considering future streams of benefits and costs.The decision rule is to reject a project that yieldsBCR that is less than 1.Example (e): Referring to example (d), we note the following information:Present value of benefits = P 248,258.99Present value of costs = P 98,258.99PV of benefitsBCR = = 2.53PV of cos tsIn other words, we enjoy benefits amounting to more than 2 and ½ times the amount wespent for the project.RGEdillon January 20069

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentExample (f) using Microsoft Excel:The computation of the IRR is quite involved and requires a combination of interpolationtechniques and trial-and-error. Fortunately, this function is found in Microsoft Excel sothe computation is now easy.Consider the above example. We can lay out the data on costs and benefits accruing toeach year. We then compute for the undiscounted net benefits (benefits less cost).Year Costs BenefitsBenefits lessCost0 150,000.00 (150,000.00)1 -2 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.003 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.004 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.005 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00IRR =The procedure IRR is found in Microsoft Excel under the Main Menu “Insert”, submenu“function”.RGEdillon January 2006<strong>10</strong>

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentYou will then be shown a list of functions that are in the software. Choose the functioncategory (left side of the box) “Financial” and under function name (right side of the box),choose ‘IRR”.RGEdillon January 200611

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentA dialog box appears and you will be asked to indicate the data range corresponding tothe “values”.Year Costs BenefitsBenefits lessCost0 150,000.00 (150,000.00)1 -2 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.003 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.004 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.005 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00IRR = 34%Note that the dialog box also asks another information, that is, “guess”. This is becausein some cases, the IRR may not exist or there may be multiple values of the IRR.RGEdillon January 200612

Project Evaluation and Development17. Cost-effectiveness ratio (CER). Sometimes, it is difficult to quantify project outcomes, asin the case of health, sanitation and education projects. In cases like these, the projectunder evaluation is compared against other projects that will yield the same outcomes.The appropriate indicator to compare is the cost per unit outcome, e.g., cost per childimmunized or cost per cases found and treated, etc.The decision rule is to reject a project that yields thehighest CER, or cost per unit outcome, among allpossible strategies that produce the same outcome.18. Financial and economic viability.18.1 If the project yields a positive NPV where the costs and benefits are expressed inmarket prices, the project is said to be financially viable. We also say that a projectis financially viable if the project yields an internal rate of return (financial internalrate of return) that is higher than the financial rate of discount.18.2 If the project yields a NPV where the costs and benefits are expressed in economicprices, the project is said to be economically viable. We also say that a project iseconomically viable if the project yields an internal rate of return (economic internalrate of return) that is higher than the social rate of discount.C. OVERVIEW OF PROJECT DEVELOPMENT1. As the phrase implies, project development is a process, wherein the project undergoestransition from inception to completion. It covers the following sub-processes:Pre-investmentProject identificationProject preparationProject appraisal and financingInvestmentDetailed engineering and designProject implementationPost-investmentProject operationEx-post evaluation2. Note that the project identification is undertaken beginning with the planning stage (PDP)and refined during the investment programming stage (PDIP and AIP). During projectpreparation stage, the project is evaluated and is subjected to further screening and/orfine-tuning. Projects that passed the finer screening are then appraised. It is the funder,or any party acting on behalf of the funder, that conducts the appraisal. As mentionedbefore, the interest is to verify the assumptions used and methodologies employed in thefeasibility study. There may also be other criteria for approval, aside from economicviability. Approved projects are then provided the necessary financing.3. Detailed engineering and/or design are usually undertaken only for approved projects.This is because this phase requires substantial resources, which are, in turn, built intoRGEdillon January 200613

Project Evaluation and Developmentthe project cost. Note that projects that do not involve construction of hard infrastructuredo not require detailed engineering. In such cases, only the detailed design needs to bedone. This includes the arrangements for implementation – project management, funddisbursement and accounting, monitoring and evaluation, etc. If a project is proposedfor external funding, some description of these arrangements may be already requiredbefore a project is approved.4. The next step is to implement the project according to the detailed design. For projectsthat involve construction of hard infrastructure, project operation commences only afterthe structure is built. For other projects, or for projects that include non-infrastructurecomponents, project implementation coincides with project operation. Examples of thelatter are immunization project, supplementary feeding, an irrigation project withtechnical assistance component, etc.5. Some time after the project implementation and operation, it is recommended that an expostevaluation be conducted. Results from the ex-post evaluation can enhance thedesign of future projects in order to increase its effectiveness and efficiency.6. In the next sections, we will be discussing project evaluation and development in thecontext of the project preparation stage. We will also refer to this as the <strong>PED</strong>.D. MAJOR COMPONENTS OF PROJECT EVALUATION AND DEVELOPMENT1 Earlier, we said that Project Evaluation or feasibility study pertains to a whole gamut ofanalyses undertaken to determine if the project is worth pursuing of not. Most manualson project evaluation or feasibility study enumerate and discuss the component studiesthat need to be undertaken. The usual broad classification (or sub-studies are) is thefollowing:• Market analysis• Technical analysis• Financial analysis• Economic analysis• Analysis of externalities• Risk and sensitivity analysisWe briefly describe below the objectives of these studies/analyses. The details areexplained in the subsequent sections.1.1 Market analysis answers the questions:a. Does the current situation imply that there is a shortage in supply of the project’sintended output?b. Is there a demand for the project’s output even in the medium term (say <strong>10</strong>years)?c. If I charge a fee for the use of the project’s output, by how much will demandlikely decrease?1.2 Technical analysis answers the questions:a. Is the proposed project strategy technically sound?b. What are the alternatives to produce the desired project outputs?RGEdillon January 200614

Project Evaluation and Developmentc. Is the proposed project strategy the most cost-effective among the alternativesidentified in 1.2.b?1.3 Financial analysis answers the questionsa. How much does the project cost?b. How much does it cost to operate and <strong>main</strong>tain the project so that it will beuseful?c. If the project can generate revenue, how much is the projected revenue?d. If the project cannot generate revenue, how much is the required subsidy tooperate and <strong>main</strong>tain the project?e. What is the financial internal rate of return? (See Definition 12 above.)1.4 Economic analysis answers the questions:a. How much is the true cost of the project to society (economic cost)?b. How much is the true benefit of the project’s output to society (economicbenefit)?c. How do these economic costs compare with the economic benefits?1.5 Assessment of externalities answers the questions:a. Will any of the project’s activity and output pose hazard to the environment?b. What are the potential risks to other people’s health, lives and property?c. What is the likelihood of these potential hazards?d. How can these hazards be mitigated and if possible, prevented?e. How much is the cost of mitigation and/or prevention?f. Will any of the project’s activity and output generate benefits even to theunintended beneficiaries of the project?1.6 Risk and sensitivity analysis answers the questions:a. Will the project still be financially viable if there are deviations in input and outputcosts, including the possibility of time overrun?b. Will the project still be economically viable if there are deviations in input andoutput costs, including the possibility of time overrun?2 This <strong>guidebook</strong> discusses these same components but takes a different approach. Inthis section, we provide a brief rationale of the steps involved in <strong>PED</strong>. The underlyingprinciples for the steps involved are discussed in detail in the Technical Appendix.3 In conducting <strong>PED</strong>, it is important for you to:3.1 KNOW the project and3.2 UNDERSTAND it in sufficient detail, enough to be able to3.3 ANALYZE it thoroughly, and3.4 JUDGE it fairly.E. PROJECTS TO BE SUBJECTED TO PROJECT EVALUATION AND DEVELOPMENTRGEdillon January 200615

Project Evaluation and Development1. Undertaking <strong>PED</strong> will, by themselves, entail the use of time and manpower resources.Thus, it is not advisable to subject each and every project to rigorous <strong>PED</strong>. By this, wemean that for “small” projects, the steps to be undertaken can end with “UNDERSTANDthe project”, but for “big” projects, there should be a complete analysis.2. The question that comes to mind is “How do we define big and small projects?” Thisquestion should be answered in relation to the competing needs for the fiscal resourcesof the province. A suggestion is to subject projects to the complete <strong>PED</strong> if the projectcost meets the following:Pr oject cos t>20%development fundnumber of municipalitiesThe above scheme is easily justified:2.1 If we consider one municipality to be just as important as the next, and2.2 If the project will require resources greater than the amount computed at equalsharing, then2.3 We will need to be able to defend the project to the other municipality that will haveto forgo some of its share from the “fiscal pie”.Annex 1 shows the latest IRA data (2003) of provincial LGUs and the corresponding cutoffbetween small and big projects. It is suggested that the cutoff be re-computed asnew data becomes available.3. All projects that are proposed for external funding will be subjected to thorough <strong>PED</strong>analysis, regardless of the size of the project. The reason for this is because the fundingsource will want to be assured that the funds (whether in the form of loan or aid) will, onbalance, benefit society. Note that your proposed project will have to compete againstproposed projects of other provinces and even agencies of the national government!F. PROCEDURES IN CONDUCTING <strong>PED</strong>1. KNOW THE PROJECT1.1 Before proceeding, it is important to identify the good or service that the project willprovide. Having done this, you will need to characterize this output as to:1.1.1 Whether the good is private, public or mixed. Be guided by the following setof questions: 5a. If I consume the good, does it mean that others cannot consume it?b. Can I limit consumption only to those who paid for the good?c. Is the project’s output divisible and can consumption be measured?d. Is it feasible to collect fees from the consumers?5 Please refer to the Technical Appendix, pages 2-4 for a more detailed discussion of the typology of goods andservices.RGEdillon January 200616

Project Evaluation and Developmente. Will I need to contend with congestion issues?1.1.2 Whether the good is tradeable, nontradeable or limited tradeability. Beguided by the following set of questions:a. Is the good being traded in the international market?b. From the Philippine point of view, do we import a good of similar type?c. From the Philippine point of view, do we export a good of similar type?d. Are there restrictions governing the import and export of this good?1.2 This step will help us anticipate the “pricing” problem that needs to be confrontedwhen conducting the <strong>PED</strong>.1.2.1 If the good possesses the characteristic of a private good, then users can becharged a fee. There can be revenues from the project.1.2.2 If the good is a public good, then it is either not possible or administrativelyinfeasible, to charge a user’s fee. The project benefits will not be expressedby way of revenues.1.2.3 If the good is being traded in the international market, procuring it (in the caseof inputs) and producing it (in the case of outputs) will have foreign exchangeimplications on the country. These will need to be considered in theeconomic analysis.2. UNDERSTAND THE PROJECT IN SUFFICIENT DETAILThis step is interested in answering the following:• Are the project goals and objectives in line with the goals and objectives articulatedin the PDP?• Is there a logical path coming from the proposed activities of the project to thedesired outputs and the promised outcomes and impacts?• How can the transformation from input to output to outcome and impact beimproved? Will the project require other components or other projects to effect thetransformation?Following is a series of questions that need to be answered satisfactorily to helpunderstand what the project is about. Note that the proponent is the major actor in thisphase.If the project proponent is not able to provide a satisfactoryanswer to any of the questions below, then the projectconcept is not yet fully developed. In this case, theproponent will need to go back to the “drawing board” tofinalize the project concept.2.1 What is the rationale for the project?RGEdillon January 200617

Project Evaluation and Development2.1.1 Develop the log frame for the project. 6 The project proponents, with guidancefrom the <strong>PED</strong> technician, will model the project in matrix form, clearlyspecifying thei. Goal of the sector to which the project belongs,ii. the expected impact of the project that will contribute to meeting this goal,iii. the project’s outputs that will result in the expected impact,iv. and the project’s inputs that are needed to produce the output.v. Important assumptions are stated andvi. a list of verifiable indicators of success is given,vii. together with the proposed strategy to measure accomplishment.2.1.2 Note that the Project Proponent must be able to trace the goal of the projectback to the development goals articulated in the Provincial Development Plan(PDP).Table 1MatrixNarrative Summary Indicators M&E AssumptionsGoal:Purpose:OutputsInputsExample (g): Consider a project that will construct a communal irrigation system. Thelogframe may resemble the following:6 Please refer to the Technical Appendix, pages 12-15, for a more detailed discussion of logical framework analysis.RGEdillon January 200618

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentProject: Communal Irrigation SystemNarrative Summary Indicators M&E AssumptionsGoalTo promote food securitymean and variance of domesticsupply of riceBAS recordsTo reduce poverty among rice farmerspoverty incidence among ricefarmersFIES and APISPurposeTo increase and reduce volatility in thedomestic production of riceTo increase and reduce volatility in theincome stream of rice farmersvolume of rice produced per year special evaluationis increased by 1.8 times surveynumber of harvest is at least 2 per special evaluationyearsurveyreduced variance in rice production special evaluationper yearsurveyincome of farmers from rice is special evaluationincreased by 1.8 timessurveyreduced variance in annual income special evaluationof rice farmers from ricesurveyadequate supply of farminputs; available capital topurchase farm inputs;properfarm managementadequate postharvest andstorage facilitiesaggressive marketingstrategysavings mobilizationschemes for farmersOutputsIrrigation service area with covering <strong>10</strong>0hectares of rice plainsconstruction of CIS with servicearea of <strong>10</strong>0 hectaresprojectaccomplishmentreportsproper O&M and watershedmanagementInputsPhp <strong>10</strong> millionEngineering supportAdmin supportfunds disbursement rate% accomplishmentprojectaccomplishmentreportsROW secured on time2.2 The primary function of projects is to catalyze development.2.2.1 Society will continue functioning even without the project. The proponentneeds to adequately describe the “without project” scenario and contrast thisagainst the “with project” scenario. Again, this procedure is facilitated by theproject’s logframe. Table 2 can also help. Not all cells need to be filled up,only those that are relevant to the project. However, it will be useful to collect(and regularly update) this information from every barangay in the province.a. Start with the outcome, describe the current situation.b. Forecast 7 what will be the outcome going into the future if the project willnot be undertaken. We refer to this as the “without project” scenario. Besure to consider the following:• This “without project” scenario should consider future developments.• It is not always correct to assume that over time, the “without project”scenario will simply be the value of the outcome at the initial year.• The “initial year” should not coincide with extraordinary events, like anEl Nino, an earthquake, etc., unless these are normal occurrences.c. We will need a time series to be able to forecast outcomes given the“status quo”.7 Refer to Technical Appendix, pages 16-21 for pointers and some simple techniques on demand forecasting.RGEdillon January 200619

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentExample (h): Consider the following possible time series indicating volume of riceproduction.ABCD1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8YearWe have plotted four possible scenarios – A, B, C and D. The actual time series isgiven by the black dots and the black lines. The forecast trend is given by the bluebroken line. Note that scenarios B and especially C are cases where the status quomay lead to desirable outcomes, even without the project. Scenario A warrants aproject to change the situation into a desirable one. In scenario D, the project maybe more interested in sustaining desirable outcomes.2.2.2 Why should government be engaged in providing this output? 8a. If the “without project” scenario will already result in desirable outcomes,the government need not undertake the project.b. The <strong>PED</strong> analyst should consider the alternative strategy of instituting theproper policy and regulatory framework in order to produce the sameoutcomes, instead of undertaking the project. Some guideposts to aid theanalysis are:• Can the output be packaged commercially?8 The Technical Appendix, page <strong>10</strong> discusses the Role of Government and Role of Projects in Development.RGEdillon January 200620

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentNote that to merit public provision, the answer to the previousquestion should be a NO. If the answer is YES, we need to resolvethe following issues next:• Will it be profitable to private entrepreneurs? At what price should theoutput be sold for it to be an attractive commercial undertaking?• At this price, will consumers be able to afford it? What is the adverseeffect if the intended beneficiaries will not “buy” the good or service?• Is there enough private capital to undertake the investment to producethe output?• Just how soon can private investment be expected to start?• In case of regulation, how will compliance be monitored?Example (i.1): If the interest is to produce irrigation services, the obviousalternative is for individual farmers to put up their own shallow tube wells.If government updates the hydrological map of the province, will this beenough to encourage farmers to undertake the investment?Example (i.2): The private sector is also engaged in providing educationservice. However, this means that they will charge tuition fees. Can thefamilies of the potential student afford the fees? Will this discourageschool participation?Example (i.3): The provincial LGU plans to showcase the province’sscenic spots by hosting a national event. However, there are not enoughlodging places to house the prospective delegates. Should the LGUconstruct lodging facilities? Or can the private sector be encouraged toconstruct the facility? What will it take? Suppose the LGU constructs aconference facility and present plans to encourage tourism and use of theconference facility, will this be sufficient “come-on” for the private sector?Example (i.4): In highly urbanized areas, the private sector may beenticed to build and operate the public market. BUT, they will want to beassured that the LGU will not allow sidewalk vendors to operate in closeproximity to the “strategic” site identified.2.2.3 It is also important to trace the output and outcome pathways of the project.This will identify any pre-conditions for the project to generate output. On thisbasis, we can classify the project as:a. (S) Stand-alone – meaning that it can produce output on its ownb. (R) Required project – meaning that it provides the enabling mechanismfor other projects to produce output. The project can be analyzed as astand-alone or as component of a package of projects.c. (C) Needs a Companion project – meaning that its ability to produceoutput depends on the success of another project. The project needs tobe packaged with the other project that provides the “enablingmechanism.”RGEdillon January 200621

Project Evaluation and Development2.2.4 In the preceding step, the <strong>PED</strong> analyst needs to refer back to the PDIP. Oneshould watch out for projects that have been forcibly subdivided in order toescape being subjected to a complete <strong>PED</strong>. A possible red flag is forprojects that are proposed to be implemented in the same locality.Example (h): Consider again the P <strong>10</strong> million Communal Irrigation Project. Theexpected output is a communal irrigation system that will generate <strong>10</strong>0 hectares ofirrigation service area. The expected outcome is increased cropping intensity,leading to increased palay production and reduced volatility in the supply of palay.The expected impact is increased farm income of the farmer beneficiaries andreduced volatility in income stream. The pathway may be illustrated as follows:P <strong>10</strong> million projectAdmin costIncreased Cropping intensityIncreased Palay outputReduced volatility in supplyIncreased Farm incomeReduced volatility in income streamThe <strong>main</strong> diagnostic question is: Is the irrigation system all that is needed toincrease cropping intensity, increase palay output and reduce volatility in supply?In other words, does it qualify as a stand-alone project? Obviously not.Constructing an irrigation system will not be enough to produce the outcome thatthe project promises. We know that, in addition to good weather, there has to beadequate water supply for the CIS to be able to provide irrigation service. Thus,we should include as project component systems for watershed managementand proper operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance of the CIS. Proper farm managementhas a direct effect on farm output. We may want to enhance current practices byproviding technical assistance to farmers. Now, from increased farm output toincreased farm income, there is the intermediate process of postharvest andmarketing. We may want to include components in the project that enhance theefficiency of postharvest facilities and improves the marketing strategies of thefarmers.RGEdillon January 200622

Project Evaluation and DevelopmentP <strong>10</strong> million projectAdmin costOther costsGood weatherReliable water supplyProper farm mgtWatershed Mgt SystemProper O&M of CISTechnologyIncreased Cropping intensityIncreased Palay outputReduced volatility in supplyPostharvest efficiencyMarketing strategyIncreased Farm incomeReduced volatility in income streamWith the inclusion of these additional components, we must realize that theproject will now cost more than P <strong>10</strong> million. It will also produce additionaloutputs, say:• Watershed management systems and procedures• Manual of systems and procedures for the O&M of the CIS• Number of farmer field schools established• Modern postharvest facility• Organization of marketing and/or farmers’ trading cooperativesRGEdillon January 200623

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning and Expenditure Management and DevelopmentName of Community:Table 2PERMANENT PROFILEMunicipalityBarangays Covered:Distance from town centerTopographyClimateSoil typeWater resourcesLand area of which: Agri. area:Income class:Without Project SituationPUBLIC AND PRIVATE FACILITESWith Project SituationFacilities for Agri ProdnPostharvest facilitesAgri-processing facilitiesIrrigation systemsRoads and BridgesTraining facilitiesPotable water supply # hh served # hh servedLevel ILevel ILevel IILevel IILevel IIILevel IIIHealth facilitiesEducational facilitiesRGEdillon January 200624

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning and Expenditure Management and DevelopmentName of Community:Table 2 (page 2)VARIABLE PROFILEHuman CapitalPopulation people householdsGrowth rateAge-Sex DistributionMale Female Total 65Labor Forceof which% in agriculture# of days employed per yearHealth StatusMortality rateMorbidity rateNutritional Status of PS Status # of PS Status # of PSNormalNormal1st degree1st degree2nd degree2nd degree3rd degree3rd degreeTOTALTOTALOther RemarksRGEdillon January 200625

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning and Expenditure Management and DevelopmentName of Community:Table 2 (page 3)Income ProfileAve. hh farm incomeAve. hh nonfarm incomeAve hh incomeIncome opportunitiesFarmingCropping pattern Major crops Area planted T Yield Gross Return Cost of prodn Major crops Area planted Yield Gross Return Cost of ProdnLivestock Livestock Number Gross Return Cost of Prodn Livestock Number Gross Return Cost of ProdnEnterprise Enterprise Capitalization Net Income No. employed EnterpriseCapitalization Net Income No. employedRGEdillon January 200626

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning andExpenditure Management and DevelopmentTable 2 (page 4)Name of Community:Fixed wage Establishment No. employed Ave. wage Establishment No. employedAve. wageTechnological profileFarming technologyAccess to technologyFinancial CapitalAccess to formal credit institutionsLending Inst # who access Status Lending Inst # who access StatusAccess to informal credit institutionsMarketing OutletRGEdillon January 200627

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Development3. ANALYZE IT THOROUGHLYAt this stage, we are left only with “big” projects or those that are to be fundedexternally and all of these passed the initial screening (i.e., the steps in KNOW andUNDERSTAND the project).To ensure that the same standard is applied across the different projects, following isa series of questions that need to be answered satisfactorily.A project may be screened out if the answer to any of theseis not satisfactory. Moreover, since the questions need tobe asked in sequence, once the answer to one isunsatisfactory, the re<strong>main</strong>ing questions need not be asked.3.1 What is the market situation like for the project’s output? 93.1.1 We can have an idea of the likely demand for the project’s output byobserving the existing demand and supply of the same good. If thedemand is more than the supply of the good, then clearly, there is a supplygap and this can be filled up by the project’s output.Example (j): Long queues at hospitals and clinics imply a shortage in the supply ofhealth care facilities. Overcrowded classrooms indicate a shortage in the supply ofclassrooms (and even teachers). High incidence of absenteeism during certainschool days (say, rainy season) may indicate poor access of the classroom to thehouses of the students.Example (k): Consider a proposal from Community C to construct a schoolbuilding.At present, the nearest school is more than an hour’s walk from the house nearest totheir barangay hall. Below is their projected demand, based on population projectionof the age cohort 6-12 years old.RequiredProject number ofschoolersnumber ofclassroomsYear 0Year 1 287 7Year 2 296 7Year 3 305 8Year 4 314 8Year 5 334 8Year 6 354 9Year 7 374 9Year 8 394 <strong>10</strong>Year 9 414 <strong>10</strong>Year <strong>10</strong> 434 119 This is similar to market analysis.RGEdillon January 200628

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentGiven the above profile, we may consider putting up a 7-classroom building andpossible expansion on year 6.3.1.2 The relevant questions to ask in describing the market situation are thefollowing:a. Is there a demand for the project’s output?b. Is there a current supply of a good similar to the project’s output? Forhow much is the good being sold?c. Is there a supply gap?d. How responsive do you think is the level of demand to the price of thegood? This is what we refer to as elasticity of demand.e. How responsive do you think is the level of current supply to the priceof the good? This is what we refer to as elasticity of supply.We may construct a matrix, like the one below, to summarize theseanswers.Table 3Project output 1Without projectCurrentdemandCurrentsupplyWith projectlevelpriceelasticityForecastdemandForecastsupplySupply fromprojectSupply fromother sourceslevelpriceelasticityASSUMPTIONS and SOURCES OF DATAImportant Notes:In most cases, you cannot rely on surveys or data released by the PhilippineStatistical System, especially if you require sub-provincial disaggregation of the data.However, the departments concerned (within the provincial LGU) collectsRGEdillon January 200629

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentadministrative data that can be used for this purpose. An alternative is to conduct aninterview with key informants to arrive at a rough estimate.Estimating demand and supply elasticities is a complex and sophisticated process,even for economists <strong>10</strong> . For purposes of the Project Evaluation, we need only toknow if demand (or supply) is price elastic or inelastic. If you are conducting a keyinformants interview, you simply ask the following series of questions:a. If the good or service is provided for free, how many do you think will avail ofthe good or service?b. If we charge a price, say Php <strong>10</strong>0 per unit (or per use or per month), howmany do you think will be willing to avail of the good or service?c. You can then vary the price quotation in b, until you arrive at the followingtable:Label Price (P) Potential Demand (D)(P 0 , D 0 ) free <strong>10</strong>0 users(P 1 , D 1 ) <strong>10</strong>0 50 users(P 2 , D 2 ) 50 75In computing the elasticity, we disregard the information on potential demandwhen the price is free. The estimate of elasticity is given by the followingformula:εDPln ( D2) − ln ( D1)=ln ( P ) − ln ( P)2 1The function ln corresponds to the natural logarithm. In the above example,we compute the following:ε DPln (75) − ln (50)= =−0.58496ln (50) − ln (<strong>10</strong>0)3.2 Is the project technically feasible?3.2.1 The <strong>PED</strong> technician may enlist the help of other experts, especiallyengineers, to identify the alternative to the project. What other projectswill produce the output that the project under analysis is promising toproduce?3.2.2 In general, the type of provision may differ according to the following:a. Fixed capital requirements (land, location, resource base)b. Production techniquec. Level and quality of supply<strong>10</strong> See Technical Appendix, pages 6-7; 23-24, for a more detailed discussion of elasticity.RGEdillon January 200630

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentd. Investment lage. Requirements for operations and <strong>main</strong>tenancef. Economic lifeTable 4Fixed capital rqmts Production SupplyOutput Option Land Location technique Level Quality O&M costEconomicLife3.2.3 The project must be rated as the most cost-effective among alltechnically feasible options. The above table may be revised asnecessary. What is important is the process of considering otherpossible alternatives.Example (l): Consider the following two examples. The first project aims toprovide irrigation service. There are four options that can be considered.The first two – A1 and A2 - differs only with respect to location of the CIS,whether Barangay A or B. If the project is located in Barangay B, the projectwill be more expensive in unit terms and coverage will be reduced. The othertwo options – B and C are not technically feasible.RGEdillon January 200631

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentProject output Option Type of project Location Total Cost Amount of Supply Remarksirrigation service A1 CIS Barangay A Php <strong>10</strong> million <strong>10</strong>0 has. more cost-effectiveA2 Barangay B Php 6 million 50 has. less cost-effectiveB STWC SFRno shallow aquiferno feasible siteclassrooms D Barangay A 2,800,000.00 7 classrooms for further evaluationD1 Barangay B 2,800,000.00 7 classroomstarget pupils arefrom Barangay A.From A to B ismaximum of 2 hourswalkclassrooms +access roadD2 Barangay B 12,800,000.00 7 classrooms + <strong>10</strong> for further evaluationkms. of roadThe second project aims to build a schoolbuilding with 7 classrooms. Thetarget pupils are in Barangay A. We can consider three options:• Option D will build the school in Barangay A.• Option D1, will add classrooms to the nearby school in Barangay B,but this will entail at most a 2-hour walk for Barangay A pupils.• Option D2 – add classrooms to school in Barangay B and constructan access road from Barangay A to B.The least desirable is Option D1. Meanwhile, we will need to consideroption D in comparison with option D2.3.3 How much will the project cost? Can we sustain project operations?3.3.1 Following is a series of questions that the Project Proponent must beable to answer with reasonable accuracy. The <strong>PED</strong> technician mustverify the basis of the answers.a. How much is needed to operate and <strong>main</strong>tain the project in usableform?b. If we can charge user fees, how much should it be? How muchmore is needed to collect the fees (administrative cost of collectingthe fees)?c. Given the fees, what is the projected number of users?d. If we do not collect the fees, what is the projected number of users?e. If the project cannot be expected to pay for itself, will the provincialgovernment be willing to subsidize its operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance?By how much?RGEdillon January 200632

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentThis phase of the study is similar to financial analysis. It differs only interms of rigor and emphasis where our interest concerns publicprovision of goods and services and not profitability.The answers to c and d depend on the assumed elasticity of demand.3.3.2 Projects that will be subjected to the review and approval procedures ofthe Investment Coordinating Committee (ICC) need to accomplishprescribed forms. ICC Form 3 asks for the cost of the project duringthe investment phase while ICC Form 4 asks for the operating and<strong>main</strong>tenance costs. These forms are attached as Annexes 2 and 3,respectively.3.3.3 For projects that will not be subjected to ICC review and approval, wemay use Table 2 in answering the above questions.We may summarize the answers to the above questions in a simple tableof costs, benefits and revenue projections with explicit consideration fortiming. The simple table can be of the following form:Table 5Year123456789<strong>10</strong>Costs Benefits RevenuesOperationsandNumber ofNumber ofNetInvestment Maintenance per user Users Total Unit fee users Admin Cost RevenuesA B C D E = C*D F G H I=F* G-H3.3.4 Alternatively, we may use a more sophisticated table of financial flows.The information will have to be provided by a finance officer oraccountant of the department concerned. Note that this step can betaken up in the feasibility study, that is, if the project passed the prefeasibilitystage.The following is taken from NEDA (2000).Financial receipts:SalesLess: Changes in Account ReceivablesResidual valuesLandEquipmentRGEdillon January 200633

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentBuildingsTotal InflowsFinancial expenditures:Investment Expenditures/Opportunity CostsNew investmentLandType 1 EquipmentType 2 EquipmentBuildingsExisting assets (if any)LandEquipmentBuildingsOperating ExpendituresRaw material (1)Raw material (2)Raw material (n)ManagementSkilled laborUnskilled laborMaintenanceLess: Changes in Account PayableLess: Changes in Cash BalanceTotal OutflowsNet Cashflow3.3.5 At the pre-feasibility stage, it may be too much to require the ProjectProponent to submit the information listed in 3.3.3. An alternative is torequire a simple schedule of cash flows, clearly indicating the timingand the amount of receipts and expenditures.Cash flow analysis differs from normal accounting in the followingrespects 11 :a. In normal accounting, income and expenditure represent the valuesof goods or services delivered and received. In cash flow analysis,we consider cash received and cash paid out for them.b. Normal accounting shows financial liabilities with respect to interestand tax. In cash flow analysis, we reflect payments.c. A financial allowance for depreciation and obsolescence of capitalis made in normal accounting. In cash flow accounting, we onlyconsider anticipated renewals and replacements as well as thescrap value of the equipment. The latter is reflected on the lastyear of the economic life of the equipment.11 Taken from Little and Mirrlees (1974).RGEdillon January 200634

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Development3.3.6 It should be obvious by now that we can conduct a cash flow analysisonly for projects that are expected to generate revenues. However,even for projects that will not generate revenues, it is still useful to havean estimate of the cash flow. At the very least, this informs us of thetiming of the need for subsidies.The following example illustrates a simplified cash flow analysis thatcan be useful in anticipating the need for subsidies. This will serve thepurposes of a pre-feasibility study. For the feasibility study, a morerigorous cash flow analysis needs to be undertaken. Following are thesimplified steps:a. Forecast the cash outflow - investment costs, cost of operations,<strong>main</strong>tenance and administration by yearb. Forecast the cash inflow (revenue from all users/uses of theproject’s output by year.c. Get the difference between cash inflow and cash outflow.d. Convert the difference in present value terms. Get the sum. This isyour NPVe. Analyze the cash flow:Beginning balance (year t) = Ending balance (year t-1)Ending balance (year t-1) = Beginning balance (year t-1) +[Cash inflow (year t-1) – Cash outflow (year t-1).]f. Convert the figures derived from e into present values.At this point, we have an idea of the cost of investment, operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance as wellas the potential revenue of the project. The decision rule is:If operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance of the project cannot besustained, either from project revenues or subsidies fromthe province, the project investment should not beundertaken.RGEdillon January 200635

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning and Expenditure Managementand DevelopmentExample (m): Consider the following very simple schedule of projected cash flows of our irrigation project. It has a servicearea of <strong>10</strong>0 hectares. It costs a total of P <strong>10</strong> million to build, requires regular <strong>main</strong>tenance costing P 1500 per hectare peryear and periodic <strong>main</strong>tenance costing P 5000 per hectare every 5 years. The irrigation service fee is <strong>10</strong>0 kg of palay perhectare during the wet season and 150 kg/ha during the dry season. Let us first assume no escalation of relative prices, thatis, the cost of operating and <strong>main</strong>taining the facility will just move with the price of palay, equal to Php 11.00 per kg. We alsoassume a residual value of 1% of investment cost. Below is the projected cash flow.The first thing we note is that the irrigation project is really a losing proposition if benefits are reckoned only at the possible ISFcollection. The NPV is negative. This also means that it is not an attractive undertaking for the private sector. Consider the nexttwo tables where we look at cash flow and where we should be prepared to offer subsidies:RGEdillon January 200636

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentUndiscounted Cash FlowsBeginningBalanceIn less Out forthe Year Ending Balance0 (4,000,000.00) (4,000,000.00)1 (4,000,000.00) (5,945,000.00) (9,945,000.00)2 (9,945,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,844,000.00)3 (9,844,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,743,000.00)4 (9,743,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,642,000.00)5 (9,642,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,541,000.00)6 (9,541,000.00) (249,000.00) (9,790,000.00)7 (9,790,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,689,000.00)8 (9,689,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,588,000.00)9 (9,588,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,487,000.00)<strong>10</strong> (9,487,000.00) <strong>10</strong>1,000.00 (9,386,000.00)11 (9,386,000.00) (249,000.00) (9,635,000.00)12 (9,635,000.00) 201,000.00 (9,434,000.00)The above table implies that the project will not be able to pay for the cost of development,operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance out of the ISF collection. It appears that government will needto subsidize both the operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance.The alternative is to consider the cost of development as a grant. Another option is torequire counterpart payment. This latter option also fosters a sense of ownership amongthe farmer-users and may lead to more efficient operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance of the facility.The next table is the cash flow analysis. Note that it is constructed from the point of view ofthe farmers (or irrigators’ association) so that the development grant, amounting to P 4million and P 6million during years 0 and 1 (respectively) are treated as an inflow. The ISFcollection will then be able to finance the operations and <strong>main</strong>tenance as well as shoulderthe re<strong>main</strong>der of the loan.The debt payment is pegged at P 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 each year. Note that labor payments foroperations and <strong>main</strong>tenance is now P<strong>10</strong>,000.00. This means that we expect the irrigator’sassociation to provide labor counterpart as well. Still, government needs to extendassistance (which can be in terms of a loan) to finance the periodic <strong>main</strong>tenance on years6 and 11. In both years, the assistance will amount to P 345,000 in real terms,undiscounted. We recommend that the assistance on year 6 be treated as a grant whilethe assistance on year 11 be treated as partly grant, partly loan.The second table below shows the cash flow analysis from the point of view of LGU, sothat debt payment of the IA is treated as debt receipt and grants are treated as outflows.Note that this latter scheme results in slightly less burden on the LGU (PHP -8.87 million,discounted at 15%). Still, the very important question that should be answered is: “Is theprovince willing to extend this type of assistance? How can this subsidy and assistance bejustified?”RGEdillon January 200638

Strengthening Provincial/Local Project EvaluationPlanning and Expenditure Managementand DevelopmentInvestmentYear Phase (Total) Personnel MOOECash OutflowOperating PhaseCash Flow Analysis from the Point of View of the Irrigators' AssociationCash InflowMaintenanceCosts Debt Payment Total OutflowIrrigationService Fee Residual value Grant TOTALIN LESS OUT(CURRENTYEAR)Cash Flow0 4,000,000.00 4,000,000.00 4,000,000.00 4,000,000.00 - -1 6,000,000.00 6,000,000.00 55,000.00 5,945,000.00 6,000,000.00 - -2 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.003 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 2,000.004 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 3,000.005 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 4,000.006 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 500,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 624,000.00 275,000.00 345,000.00 620,000.00 (4,000.00) -7 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.008 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 2,000.009 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 3,000.00<strong>10</strong> <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 274,000.00 275,000.00 275,000.00 1,000.00 4,000.0011 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 500,000.00 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 624,000.00 275,000.00 345,000.00 620,000.00 (4,000.00) -12 <strong>10</strong>,000.00 4,000.00 150,000.00 2<strong>10</strong>,000.00 374,000.00 275,000.00 <strong>10</strong>0,000.00 375,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00Cash Flow Analysis from the Point of View of the LGUDebt Receipts Grant IN less OUT PV at 15%0 - 4,000,000.00 (4,000,000.00) (4,000,000.00)1 - 5,945,000.00 (5,945,000.00) (5,169,565.22)2 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 83,175.803 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 72,326.794 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 62,892.865 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 54,689.446 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 345,000.00 (235,000.00) (<strong>10</strong>1,596.99)7 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 41,353.078 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 35,959.209 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 31,268.87<strong>10</strong> 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 27,190.3211 1<strong>10</strong>,000.00 345,000.00 (235,000.00) (50,511.66)12 2<strong>10</strong>,000.00 - 2<strong>10</strong>,000.00 39,250.50NPV (8,873,567.02)RGEdillon January 200639

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Development4. JUDGE IT FAIRLYThus far, we have achieved the following:• We already know the project• We understand it in sufficient detail• We analyzed it thoroughlyWe are now ready to judge the project on the basis of its true cost and benefits tosociety. 12 If at this point you feel that you do not yet have an in-depth grasp of theproject, you may want to ask the proponents to run by you again the above pointspertaining to the project.4.1 How much is the true cost of the project to society?4.1.1 Clarification of Conceptsa. The true cost of a good or service is sometimes referred to as itseconomic cost. The use of the term “economic” is deliberate in that weare interested in knowing the scarcity of the good or service in relation toother goods or services.b. The basic premise behind economic pricing is that the market price doesnot accurately inform us of the true value of the good or service. Rather,the market price is distorted by taxes, subsidies, transport and handlingcosts. 13c. The economic cost is given by the undistorted price at which suppliers arewilling to sell a given quantity of their produce. This means that we needto know the supply price, corrected for distortions such as taxes,subsidies, transport and handling costs.Example (m): Consider a unit of good that costs P 220 per bag, inclusive of a <strong>10</strong>%VAT. What this means is that only P 200 is received by the seller of the good, the P20 is remitted to government. Thus, the economic cost of this good 14 is P 200, andnot P 220.4.1.2 Classification of Inputs.To guide the determination of economic costs, we need to indicate thefollowing for each major project input:a. If the good is wholly tradeable, partly tradeable or wholly nontradeable12 Before proceeding, it must be mentioned that the techniques to be discussed henceforth are more complex. It issuggested that the reader go through this entire subsection, proceed to the Technical Appendix then review thissubsection once again.13 Please refer to the Technical Appendix, pages 7-9, for a more detailed explanation.14 We implicitly assume that the good is nontradeable.RGEdillon January 200640

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentBy tradeable, we mean that the good is being demanded and/or suppliedin the international market. The National Statistics Office keeps track ofexternal trade statistics and this provides information on whether the goodis being imported or exported.b. If wholly tradeable, is it an exportable or importable good?If the domestic price of the good is less than the freight-on-board (FOB)price at the border, then the good must be exportable. On the otherhand, if the domestic price of the good is higher than the cost-ofinsurance-and-freight(CIF) price at the border, then the good must beimportable. Again, external trade statistics can provide the necessaryinformation.c. If partly tradeable, what proportion of the cost is due to tradeable inputs?d. For projects to be funded internally, we can skip questions a-c and simplyanswer: How much is the cost of the good at the project site? Net oftaxes?The following matrix may be useful in summarizing this information:Table 6Major ProjectInput Tradeable ? % TradeableExportable?Importable?Cost at projectsite known?How much is theunit cost?4.1.3 Computation of Economic Cost. The computation of economic cost dependson whether the good is wholly tradeable (importable or exportable), partlytradeable or non-tradeable.i. Good is non-tradeable.• The true cost is a weighted average of the demand and supply prices.d d s sP= w *P + w *P ;d sw + w = 1RGEdillon January 200641

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentwhere w d is the weight given to demand and w s is the weight given tosupply; P d is the demand price and P s is the supply price.• Recall that the demand price is the price that consumers pay for thegood while supply price is the price that producers receive for thegood. The demand and supply prices differ from the market price bythe amount of the tax or subsidy.Example (n): <strong>10</strong>% VAT on lighting bulbs that cost Php 25, net of taxes.Demand price = Php 25 * (1+<strong>10</strong>%) = Php 27.50Supply price = Php 25Example (o): Php 3 subsidy to producers per kilo of sugar. Market price is Php30Demand price = Php 30Supply price = Php 30 + 3• In the Technical Appendix we explain in detail why a weighting isdone between the demand and supply prices. The over-simplifiedreason is that the project will result in additional input demand, saydemand for cement, etc. Under certain conditions, it can push pricesup, thus forcing other consumers to buy at a higher price. Just howmuch higher will depend on the relative elasticities of the demand andsupply.• We usually just choose among the following weights, corresponding todifferent assumptions on demand and supply elasticities.Table 7Weighting Demand price Supply priceScheme1 1.00 0.002 0.67 0.333 050 0.504 0.33 0.675 0.00 1.00• The first one assumes that price is entirely determined by demandand that supply is inelastic (quantity supplied does not respond tochanges in prices). In this case, supply may be very constrainedespecially in the short term. At the other extreme, we have the casewhere price is entirely determined by supply, meaning that demand isinelastic. There are intermediate statesScheme 2 - demand is more responsive than supplyScheme 3 – demand is just as responsive as supplyScheme 4 - demand is less responsive than supplyRGEdillon January 200642

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentii. Input good is tradeable1. In this case, the scarcity of foreign currency also needs to beconsidered in determining the true cost of the input. This is doneby imposing a foreign exchange premium (FEP) on the officialexchange rate. The value of the FEP is determined by the NEDA-PIS and may change from time to time. The most recent value is1.2.Example (p): Suppose the current exchange rate of P 54.75. With an FEP of1.2, this means that any imported input will cost 20% more when expressed indomestic currency. That is, a $ <strong>10</strong>0 worth of goods is equivalent to$ <strong>10</strong>0 x 54.75 x 1.2 = Php 6570.00in domestic currency. This is the value that will be used in subsequent economicanalysis.2. Moreover, the true cost will not include taxes and subsidies asthese are merely transfers from one economic agent to another.3. We need to further distinguish between importable and exportableinputsiii.Input good is importableEP = CIF _ price * ER * FEP + (handling _ cost less taxes) + (transport _ cost less taxes)where EP is the economic priceCIF_price is the CIF price of the good at the portER is the prevailing exchange rateFEP is the foreign exchange premium determined by NEDAHandling_cost is the cost of handling at the portTransport_cost is the cost of transporting the good from the port to the projectsiteiv. Input good is exportableEP = FOB _ price * ER * FEP + (handling _ cost less taxes) + (transport _ cost less taxes)where EP is the economic priceFOB_price is the FOB price of the good at the portER is the prevailing exchange rateFEP is the foreign exchange premium determined by NEDAHandling_cost is the cost of handling at the portTransport_cost is the cost of transporting the good from the port to the projectsitev. The good is partly tradeable, or, the good itself may be nontradeable butthe process of producing the good requires tradable goods.RGEdillon January 200643

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentt t d d s sP= s *CF*P + (1− s )*[w P + w P ]where s t is the proportion that is tradeable, CF is the conversion factor orthe amount used to express financial prices to economic prices and theothers are as defined before.vi. Labor inputsThe true cost of labor is equal to the opportunity cost of labor. Skilled laboris more scarce than unskilled labor, but the income of skilled labor istaxable while the income of unskilled labor is non-taxable. In effect, thereare negative and positive tradeoffs. In the Philippines, wages of skilledlabor is taken to be the true cost of skilled labor while wages of unskilledlabor is multiplied by a factor of 0.6 to arrive at the true cost of unskilledlabor. This conversion factor may change over time. The <strong>PED</strong> technicianshould verify with the NEDA-PIS about the current value.Example (q): Consider the following example of a rural roads project where thecost of inputs at the project site is known. Most of the inputs that will be used,e.g., gravel and sand are nontradeable but they make use of some tradeableinputs. Meanwhile, labor is considered tradeable and is valued at the opportunitycost of labor In A, we specify the cost structure of the project in terms ofmaterials, equipment and labor. This is further broken down in B into local andforeign (tradeable) component and for labor, into skilled and unskilled. Assume aforeign exchange premium of 1.2.Input Factor Financial Cost ECF Economic CostA B C D E F = D*Eof whichMaterials 40 Php326,000.00Local 40 130,400.00 1 130,400.00Foreign 60 195,600.00 1.2 234,720.00Equipment 35 285,250.00Local 25 71,312.50 1 71,312.50Foreign 75 213,937.50 1.2 256,725.00Labor 25 203,750.00Skilled 30 61,125.00 1 61,125.00Unskilled 70 142,625.00 0.6 85,575.00TOTAL Php815,000.00 815,000.00 Php839,857.50vii. The case of projects that generate negative effectsThe technical term for these negative effects is negative externalities.What is needed is to identify the cost of preventing these externalities andinclude this as part of project cost.RGEdillon January 200644

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentExample (r ) A communal irrigation project promotes the growth of parasitesthat cause schistosomiasis. The prevention measure takes the form of frequentcleaning of the canals to get rid of snails. The cleaners need to use specialequipment for cleaning. This cost as well as the labor component needs to beincluded as part of the O&M cost.Example (s): The construction of a “solar dryer” for palay exposes theneighboring residents to respiratory hazards. This can be mitigated by installingfinely-meshed nets around the solar dryer. The cost of the nets as well as thereplacement has to be included.4.2 How much is the benefit of the project truly worth to society?We value the economic benefit of the project’s output at the price that consumersare “willing to pay” for the good. Again, we consider several cases:4.2.1 Good is nontradeable.The same rules as in valuing nontradeable inputs apply. Refer to 4.1.3 a.4.2.2 Output good is importableAs in the case of importable input, we consider the CIF price, but this time, wesubtract from it the handling and transport costs from port to project site.EP = CIF _ price * ER * FEP −(handling _ cost less taxes) − (transport _ cost less taxes)where EP is the economic priceCIF_price is the CIF price of the good at the portER is the prevailing exchange rateFEP is the foreign exchange premium determined by NEDAHandling_cost is the cost of handling at the portTransport_cost is the cost of transporting the good from the port to the projectsite4.2.3 Output good is exportableAs in the case of exportable input, we consider the FOB price, but this time, wesubtract from it the handling and transport costs from port to project site.EP = FOB _ price * ER * FEP −(handling_ cost less taxes) − (transport _ cost less taxes)where EP is the economic priceFOB_price is the FOB price of the good at the portER is the prevailing exchange rateFEP is the foreign exchange premium determined by NEDAHandling_cost is the cost of handling at the portTransport_cost is the cost of transporting the good from the port to the projectsiteRGEdillon January 200645

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Development4.2.4 Some proportion of the good is tradeable.The same rules as in valuing “semi-tradeable” inputs apply. Refer to 4.1.3e.4.2.5 Labor outputs or increased labor productivityThe same rules as in valuing labor inputs apply. Refer to 4.1.3f.4.2.6 Commodity-specific Conversion Factor (CSCF)It is practical to compute for commodity-specific conversion factors for somegoods (whether inputs or outputs) that are frequently used. Commodity-specificconversion factor (CSCF) is simply the ratio between the economic price andfinancial price. Now, for the same good but pertaining to different project sites,the CSCFs will vary somewhat. Nonetheless, the previously computed CSCFsmay serve as a guide for evaluating future projects.For emphasis, recall the following differences between financial and economicprices in the case of tradeable goods.Table 8Variable Financial Price Economic PricePrice at portConverted usingprevailing exchange rateExchange rate ismultiplied by the ForeignExchange Premium(FEP)Tariffs, Taxes, subsidies Taken at full value Multiplied by a conversionfactor equal to 0Labor Taken at full value Multiplied by a conversionfactor, distinguishingbetween skilled andunskilled laborExample (t): Consider our communal irrigation project with financial cost of Php<strong>10</strong> million. Note that the classification “foreign” pertains to the tradeablecomponent, while the classification “local” pertains to the nontradeablecomponent.The CSCF is computed as follows:In column A, we specify the prevailing price, I.e., the financial price. In column B,we indicate the conversion factor. Note that taxes are given a conversion factorof 0. This is because taxes are simply considered transfers from the taxpayer togovernment; there was no additional output that was produced. In column D, wespecify the proportion that is tradeable and this amount is multiplied by theRGEdillon January 200646

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Developmentforeign exchange premium, estimated to be 1.2. The CSCF, or the ratio betweenthe economic and financial price is estimated to be 1.03 in this case.ProjectCommunal IrrigationTotal Investment Cost Factors Financial Cost ECF Economic Costof whichMaterials 40 Php4,000,000.00Local 40 1,600,000.00 1 1,600,000.00Foreign 60 2,400,000.00 1.2 2,880,000.00Equipment 35 3,500,000.00Local 25 875,000.00 1 875,000.00Foreign 75 2,625,000.00 1.2 3,150,000.00Labor 25 2,500,000.00Skilled 30 750,000.00 1 750,000.00Unskilled 70 1,750,000.00 0.6 1,050,000.00TOTAL Php<strong>10</strong>,000,000.00 <strong>10</strong>,000,000.00 Php<strong>10</strong>,305,000.00Memo: ConversionFactor 1.03RGEdillon January 200647

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand DevelopmentExample (u): In this second example, we consider a project that providestechnical assistance to farmers to improve corn productivity. We compute for theCSCF of corn as follows:Importable OutputProject Site = Community CProduct : CORNParticularsFinancialPriceUnadjustedConversionFactorUnadjustedEconomicValuePercentTradableFEP (20%)EconomicValue(Adjusted)[A] [B] [C = A * B] [D] [E = A*D*.2] [F = C + E]1 CIF $ (Manila) 212.002 CIF Php (Manila) 11,766.00 1.00 11,766.00 <strong>10</strong>0.00 2,353.20 14,119.20Plus:3 Tariff @ 352.98 0.004 VAT @ <strong>10</strong>% 1,211.90 0.005 Port Charges 300.00 1.00 300.00 30.00 18.00 318.006 VAT @ <strong>10</strong>% 30.00 0.007 13,660.88 1.00 13,660.88 <strong>10</strong>0.00 2,732.18 16,393.05Net Importer's Price (2+3+4+5+6)8 VAT 1,366.09 0.00 0.00 0.009 Importer's Price (7+8) 15,026.97 1.00 15,026.97 <strong>10</strong>0.00 3,005.39 18,032.36Less<strong>10</strong> Inter-Island freight 1,560.00 1.00 1,560.00 50.00 156.00 1,716.0011 VAT @ <strong>10</strong>% 156.00 0.0012 Port Charges and inland transpo 575.00 1.00 575.00 30.00 34.50 609.5013 VAT @ <strong>10</strong>% 57.50 0.00Price Net of Tax14 [9 - (<strong>10</strong>+11+12+13)] 12,678.47 1.00 12,678.47 <strong>10</strong>0.00 2,535.69 15,214.1615 VAT @ <strong>10</strong>% 84.96 0.0016 Factory Gate Price (14+15) 12,763.43 1.00 12,763.43 <strong>10</strong>0.00 2,552.69 15,316.1117Conversion Factor (EconomicValue/Financial Price) 1.20RGEdillon January 200648

Strengthening Provincial/LocalPlanning and Expenditure ManagementProject Evaluationand Development4.3 The case of public goods 154.3.1 There are cases when it is difficult to determine the true willingness-to-payso that whatever information we can get will clearly underestimate the truevalue of the benefit to society. We have seen this to be the case with publicgoods. There is always an incentive to free-ride. We can do either of twothings (or both):• Find a proxy for willingness-to-pay• Add to the original variable a fixed amount that will incorporate the truevalue of the benefit to society.4.3.2 The following table provides some examples.Good Willingness-to-pay Benefit to society Adjustmentirrigation service irrigation service fee food security value of rice productionreduced povertyincidence amongfarmersincreased income offarmerssafe and easy accessto water supplywater consumption feeimproved productivitygood health to (less absences frombeneficiaries work and school)environmental option value for tourismsanitation potentialreduced workload option value for time offor women womenelelctricityelectricity consumptionfeeimproved accessto informationoption value for theincreased number ofhours that can be usedfor productive purposes4.3.3 For completeness, we summarize the methodologies as surveyed by deCastillo (1998) involving several project evaluation studies.15 Although this part falls neatly into 4.2, it merits special attention particularly since most public sector projects willfall into this category.49RGEdillon January 2006