- Page 1 and 2:

Basic English Syntaxwith ExercisesM

- Page 5:

Basic English Syntaxwith ExercisesM

- Page 8 and 9:

PrefaceThe target audience for the

- Page 10 and 11:

Table of ContentsChapter 3 Basic Co

- Page 12 and 13:

Table of ContentsSuggested Answers

- Page 14 and 15:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 16 and 17:

2 Word Categories2.1 The LexiconCha

- Page 18 and 19:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 20 and 21:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 22 and 23:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 24 and 25:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 26 and 27:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 28 and 29:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 30 and 31:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 32 and 33:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 34 and 35:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 36 and 37:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 38 and 39:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 40 and 41:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 42 and 43:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 44 and 45:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 46 and 47:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 48 and 49:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 50 and 51:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 52 and 53:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 54 and 55:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 56 and 57:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 58 and 59:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 60 and 61:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 62 and 63:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 64 and 65:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 66 and 67:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 68 and 69:

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 70 and 71:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 72 and 73:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 74 and 75:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 76 and 77:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 78 and 79:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 80 and 81: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 82 and 83: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 84 and 85: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 86 and 87: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 88 and 89: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 90 and 91: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 92 and 93: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 94 and 95: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 96 and 97: Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations

- Page 99 and 100: Chapter 3Basic Concepts of Syntacti

- Page 101 and 102: X-bar TheoryNote that the X'and the

- Page 103 and 104: X-bar Theoryunderstood in this sent

- Page 105 and 106: X-bar Theory(19) XPYPX'VYPfallThese

- Page 107 and 108: X-bar Theory1.4 SpecifiersSo far we

- Page 109 and 110: X-bar Theorynoun, we conclude that

- Page 111 and 112: X-bar Theory(40) NPNPRelSNP RelS wh

- Page 113 and 114: Theoretical Aspects of MovementThe

- Page 115 and 116: Theoretical Aspects of MovementFina

- Page 117 and 118: Theoretical Aspects of Movement(61)

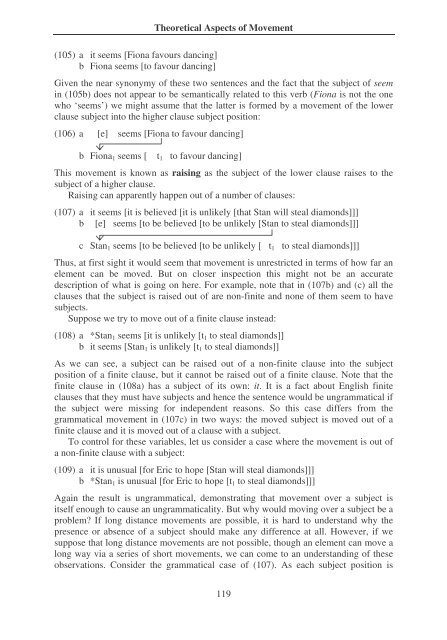

- Page 119 and 120: Theoretical Aspects of Movementassi

- Page 121 and 122: Theoretical Aspects of MovementThe

- Page 123 and 124: Theoretical Aspects of Movementmorp

- Page 125 and 126: Theoretical Aspects of Movementposs

- Page 127 and 128: Theoretical Aspects of MovementAs t

- Page 129: Theoretical Aspects of MovementTher

- Page 133 and 134: Test your knowledge6 Explain the di

- Page 135 and 136: Test your knowledge Exercise 3Decid

- Page 137 and 138: Test your knowledge Exercise 9Ident

- Page 139: Test your knowledge Exercise 17Why

- Page 142 and 143: Chapter 4 - The Determiner PhraseTh

- Page 144 and 145: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(1

- Page 146 and 147: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(1

- Page 148 and 149: Chapter 4 - The Determiner PhraseOf

- Page 150 and 151: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(3

- Page 152 and 153: Chapter 4 - The Determiner PhraseTh

- Page 154 and 155: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrasepr

- Page 156 and 157: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(6

- Page 158 and 159: Chapter 4 - The Determiner PhraseOf

- Page 160 and 161: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(7

- Page 162 and 163: Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase(3

- Page 165 and 166: Chapter 5Verb PhrasesIn this chapte

- Page 167 and 168: Event Structure and Aspectsome othe

- Page 169 and 170: Verb Types(10) a there arrived a le

- Page 171 and 172: Verb TypesThe position to which the

- Page 173 and 174: Verb TypesThe thematic relationship

- Page 175 and 176: Verb Types(39) a I broke the window

- Page 177 and 178: Verb Types(48) a Mike made the ball

- Page 179 and 180: Verb Types(54) a elmozdította a do

- Page 181 and 182:

Verb Typesconstruction in their ‘

- Page 183 and 184:

Verb Typesassumption of a position

- Page 185 and 186:

Verb Types(73) vPDPv'Pete v VPe DP

- Page 187 and 188:

Verb Types(78) vPDPv'Pete v VPagent

- Page 189 and 190:

Verb Typesand that these are passed

- Page 191 and 192:

Verb Types(90) e = e 1 : e 1 = ‘F

- Page 193 and 194:

Verb TypesbvPDPv'Ursula v vPv 2 e D

- Page 195 and 196:

Verb Types(102) vPDPv'Sam v VPsmile

- Page 197 and 198:

Verb Types(111) a Porter put the bo

- Page 199 and 200:

Verb Typeswhich the main verb moves

- Page 201 and 202:

Verb Types(125) a he lived right ne

- Page 203 and 204:

Verb TypesIn this structure, presum

- Page 205 and 206:

Verb Typesvery difficult problems f

- Page 207 and 208:

Verb TypesIn this, the verb moves f

- Page 209 and 210:

Aspectual Auxiliary Verbs2.9 Summar

- Page 211 and 212:

Aspectual Auxiliary Verbs(158) a di

- Page 213 and 214:

Aspectual Auxiliary Verbsevent (the

- Page 215 and 216:

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers4

- Page 217 and 218:

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers(

- Page 219 and 220:

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiersW

- Page 221 and 222:

Conclusion(186) a vPDPv'Harry v' Sv

- Page 223 and 224:

Test your knowledge Exercise 2Deter

- Page 225 and 226:

Chapter 6Inflectional PhrasesIn the

- Page 227 and 228:

The structure of IPIn the previous

- Page 229 and 230:

The structure of IPInflections also

- Page 231 and 232:

The syntax of inflection(17) repres

- Page 233 and 234:

The syntax of inflection(20) IP- I'

- Page 235 and 236:

The syntax of inflection(27) IP- I'

- Page 237 and 238:

The syntax of inflectionBesides the

- Page 239 and 240:

The syntax of inflectionverb cannot

- Page 241 and 242:

The syntax of inflection(44) a I th

- Page 243 and 244:

The syntax of inflection(53) a I qu

- Page 245 and 246:

3 Movement to Spec IPMovement to Sp

- Page 247 and 248:

Movement to Spec IP(60) vPDPv'they

- Page 249 and 250:

Movement to Spec IP(66) an element

- Page 251 and 252:

Conclusion(71) IPDPI'API'IvPvv'vPNo

- Page 253:

Test your knowledge Exercise 4Give

- Page 256 and 257:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser PhrasesI

- Page 258 and 259:

2 The Clause as CPChapter 7 - Compl

- Page 260 and 261:

3 Interrogative CPs3.1 Basic positi

- Page 262 and 263:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases3

- Page 264 and 265:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser PhrasesI

- Page 266 and 267:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser PhrasesT

- Page 268 and 269:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrasese

- Page 270 and 271:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser PhrasesI

- Page 272 and 273:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases(

- Page 274 and 275:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases(

- Page 276 and 277:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases(

- Page 278 and 279:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrasesa

- Page 280 and 281:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrasesa

- Page 282 and 283:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases5

- Page 284 and 285:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases(

- Page 286 and 287:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser PhrasesT

- Page 288 and 289:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases(

- Page 290 and 291:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases1

- Page 292 and 293:

Chapter 7 - Complementiser Phrases

- Page 294 and 295:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 296 and 297:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 298 and 299:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 300 and 301:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 302 and 303:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 304 and 305:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 306 and 307:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 308 and 309:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 310 and 311:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 312 and 313:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 314 and 315:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 316 and 317:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 318 and 319:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 320 and 321:

Check questionsChapter 8 - The Synt

- Page 322 and 323:

Chapter 8 - The Syntax of Non-Finit

- Page 325 and 326:

Suggested Answers and HintsChapter

- Page 327 and 328:

Exercise 2 Exercise 2A given verb m

- Page 329 and 330:

Exercise 4 Exercise 4 Exercise 5a J

- Page 331 and 332:

Exercise 7un+happi+estThis word con

- Page 333 and 334:

Exercise 10(9) a In the present sit

- Page 335 and 336:

Exercise 11Degree adverbsa cverydmo

- Page 337 and 338:

Exercise 13f Jane broke the vase.Th

- Page 339 and 340:

Check QuestionsChapter 2 Check Ques

- Page 341 and 342:

Check questionsChapter 3 Check ques

- Page 343 and 344:

Exercise 1 Exercise 1Possible confi

- Page 345 and 346:

Exercise 9will category: [+F, -N, +

- Page 347 and 348:

Exercise 11(2) VPVPYPV' adjunctV 0X

- Page 349 and 350:

Exercise 13(iii) In sentence (3a) b

- Page 351 and 352:

Exercise 14The adjunct PP is merged

- Page 353 and 354:

Exercise 15d) DPD'DaNPN'APN'tall AP

- Page 355 and 356:

Exercise 16g) NNNNorangeN cocktailj

- Page 357 and 358:

Exercise 18b) Predicate: thinkThema

- Page 359 and 360:

Check Questionsindefinite. Again, t

- Page 361 and 362:

Suggested answer forExercise 1(1) b

- Page 363 and 364:

Suggested answer forExercise 1(1) d

- Page 365 and 366:

Suggested answer forExercise 1(1) f

- Page 367 and 368:

Exercise 4 Exercise 4(1) DPDPD'the

- Page 369 and 370:

Exercise 4(3) DPD'DtheNPN'APN'most

- Page 371 and 372:

Exercise 5 Exercise 5In the Italian

- Page 373 and 374:

Exercise 8DPD'DNPanN'NPPanalysisP'P

- Page 375 and 376:

Exercise 9bDPD'D 0NPe AP N'one N 0

- Page 377 and 378:

Check Questionscontribute to the me

- Page 379 and 380:

Exercise 2Multiple complement verbs

- Page 381 and 382:

Exercise 2f Kevin killed Karen.agen

- Page 383 and 384:

Exercise 2k The window opened.theme

- Page 385 and 386:

Exercise 3 Exercise 3Verb Tense Asp

- Page 387 and 388:

Exercise 6(1) h Reorganisation of a

- Page 389 and 390:

Check Questionsoccur in embedded co

- Page 391 and 392:

Exercise 2I. Bill gets accusative C

- Page 393 and 394:

Exercise 4 Exercise 4a) In the sent

- Page 395 and 396:

Exercise 4c) The sentence David rol

- Page 397 and 398:

Exercise 4e) The verb sink is an er

- Page 399 and 400:

Exercise 4g) In the sentence Bill c

- Page 401 and 402:

Exercise 4i) The verb cough in the

- Page 403 and 404:

Exercise 4In our sentence, this pos

- Page 405 and 406:

Exercise 4m) In the sentence Jim to

- Page 407 and 408:

Exercise 4CP 3C'CIPthat DP I'Jim I

- Page 409 and 410:

Check QuesionsQ2 Main clauses in En

- Page 411 and 412:

Check Quesionsstructurally from the

- Page 413 and 414:

Exercise 3 Exercise 3e Has John eve

- Page 415 and 416:

Exercise 4(1) b raisingThe verb see

- Page 417 and 418:

Exercise 5 Exercise 5(1) a Which bo

- Page 419 and 420:

Exercise 6It is assumed that the su

- Page 421 and 422:

Exercise 7(6) a John -s like whob W

- Page 423 and 424:

Exercise 8As the grammaticality in

- Page 425 and 426:

Check QuestionsChapter 8 Check Ques

- Page 427 and 428:

Exercise 1 Exercise 1a- adjective,

- Page 429 and 430:

Exercise 4possible antecedent in th

- Page 431 and 432:

Exercise 6(v) In sentence (1e) ther

- Page 433 and 434:

Exercise 9 Exercise 9f [PRO] To err

- Page 435 and 436:

Exercise 9IPt 2I'IvPv'vvPtov'vvPhav

- Page 437 and 438:

Exercise 9IPt 4I'IvPv'vvPtov'vvPbe

- Page 439 and 440:

Exercise 9In sentence (1d) the main

- Page 441:

Exercise 9CP 7C'CIPPRO 8I'IvPv'vvPt

- Page 444 and 445:

Glossaryadjunction: a type of movem

- Page 446 and 447:

Glossarybase-generate: to insert co

- Page 448 and 449:

Glossarywhere for is used not as a

- Page 450 and 451:

Glossaryby a wh-element. The meanin

- Page 452 and 453:

Glossaryfinite verb form: a verb fo

- Page 454 and 455:

Glossarypresent approach, however,

- Page 456 and 457:

Glossarymorphological case: there i

- Page 458 and 459:

GlossaryGeneralisation), so the DP

- Page 460 and 461:

Glossarypronominal: those DPs that

- Page 462 and 463:

Glossaryspecifier rule: one of the

- Page 464 and 465:

Glossarytrace: moved constituents l

- Page 466 and 467:

Glossarywh-relative: a relative cla

- Page 468 and 469:

IndexA.adjacency 221adjective 11, 1

- Page 470 and 471:

IndexD.dative alternate see dative

- Page 472 and 473:

Indexmorphology 31, 33, 43, 75, 76,

- Page 474 and 475:

Indexmissing subject 100, 190, 225,

![Letöltés egy fájlban [4.3 MB - PDF]](https://img.yumpu.com/50159926/1/180x260/letaltacs-egy-fajlban-43-mb-pdf.jpg?quality=85)