Looking at employment - Nacro

Looking at employment - Nacro

Looking at employment - Nacro

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

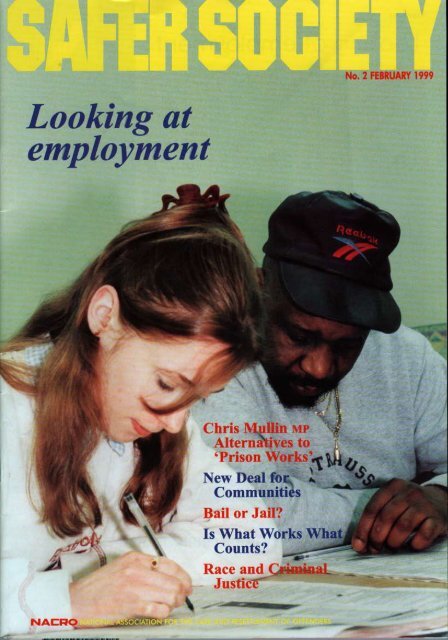

EDITORIAL<strong>Looking</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>employment</strong>‘A suitable ex-offenderemployed today may be onecrime prevented tomorrow.’Douglas Hurd, 1988‘A job is the best help th<strong>at</strong>any ex-offender can get toavoid returning to crime.’Jack Straw, 1997Two Home Secretaries, a decade apart. Itseems th<strong>at</strong> both Labour and Conserv<strong>at</strong>ivegovernments can accept the idea th<strong>at</strong> a safersociety is one in which people with criminalrecords are not excluded from the labour market.In this, the second edition of Safer Society, wefocus principally on offender <strong>employment</strong>,community regener<strong>at</strong>ion and the links betweenpenal policies and social exclusion.Chris Mullin MP st<strong>at</strong>es his view th<strong>at</strong> the‘prison works’ philosophy is <strong>at</strong> an end. Wehope he is not being too optimistic. Inidentifying educ<strong>at</strong>ion, training and<strong>employment</strong> as the keys to tackling the yobculture blighting Britain's poorestneighbourhoods he endorses the ‘work works’message taken up by Rob Allen in hisoverview of regener<strong>at</strong>ion initi<strong>at</strong>ives and byAndrew McCall in his tour d’horizon ofEuropean offender <strong>employment</strong> str<strong>at</strong>egies.Getting offenders into work rests equally onthe success of two tasks: giving themeconomically-useful skills and stimul<strong>at</strong>ingdemand for those skills. Skills development isperhaps the easier job, although throughoutEurope it is made unnecessarily difficult bynear-chaotic policy environments and byinstitutional and funding architectures in needof extensive remodelling.Increasing <strong>employment</strong> opportunity will be aSisyphian task without an onslaught onemployer <strong>at</strong>titudes - and the UK Governmentmust be alive to the potential for harm offeredby too clumsy an introduction of new criminalrecord checking arrangements - and arecognition of the limit<strong>at</strong>ions of supply-sidemeasures. Mike Stewart's piece onIntermedi<strong>at</strong>e Labour Markets describes oneway in which we can begin to bridge thedemand gap in areas of low indigenousinvestment and deliver an array of socialbenefits: good value for taxpayers' money ifall the outputs are counted. A forthcomingNACRO report, Going Straight to Work, willmake the case for renewed action to elimin<strong>at</strong>eunfair discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion against offenders andex-offenders in the job market and launch aniniti<strong>at</strong>ive to enlist major employers in thepromotion of better, fairer recruitmentpractices. This initi<strong>at</strong>ive will be covered in thenext edition of Safer Society.The Government continues to emphasise thecentrality of community safety and crimereduction to its welfare to work,neighbourhood renewal and anti-schoolexclusion initi<strong>at</strong>ives. We welcome this ‘joinedup thinking’ - indeed, Safer Society aims topromote just such a holistic approach tocre<strong>at</strong>ing inclusive and particip<strong>at</strong>ivecommunities. There remains the danger,however, th<strong>at</strong> some large-scale interventions -the New Deal for young people is an example- will fail to touch many of the hardest tohelp. There are disturbing signs in some areasth<strong>at</strong> less motiv<strong>at</strong>ed youngsters are failing tonegoti<strong>at</strong>e the complic<strong>at</strong>ed g<strong>at</strong>eway phase,despite the best efforts of the (new andimproved) Employment Service.Also in this edition Keith Towler announcesNACRO's community remand initi<strong>at</strong>ive andRob Allen looks critically <strong>at</strong> the doctrine ofevidence-based practice. StephanieBraithwaite describes the part medi<strong>at</strong>ion canplay in restor<strong>at</strong>ive justice and Anne Dunnanalyses disturbing Home Office findingswhich show th<strong>at</strong> people from minority ethnicgroups continue to be dealt withdisproportion<strong>at</strong>ely harshly by the criminaljustice system.Again, we hope the magazine highlights thefact th<strong>at</strong> str<strong>at</strong>egies for cre<strong>at</strong>ing a fairer andsafer society cannot be viewed in isol<strong>at</strong>ionfrom each other.We hope th<strong>at</strong> this second edition of the magazine is succeeding in its aim to provideinform<strong>at</strong>ion and ideas about making society safer. The editorial board would welcome yourletters in response to issues discussed or suggestions for items in future edtions.NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE CARE AND RESETTLEMENT OF OFFENDERS169 Clapham Road, London SW9 0PU Telephone 0171 582 6500 Fax 0171 735 4666ISSN 1464-8415NACRO IS A REGISTERED CHARITYThe views expressed in the articles in the magazine do not necessarily reflect the views of the Safer Society editorial board.PHOTOS: Right and front cover by Mark Harvey, iD•8, Sheffield Cover photo: Posed byparticipants <strong>at</strong> NACRO Sheffield NCT.

ContentsCHRIS MULLIN MP page 2The Chairman of theHome AffairsCommittee puts theCommittee’s report on‘Altern<strong>at</strong>ives to PrisonSentences’ in context.NEWS see boxopposite page 5FEATURES page 11Safety ThroughRegener<strong>at</strong>ion 11Rob Allen analyses thekey issues which willdetermine the successor failure of the NewDeal for Communitiesand other programmesEmploying Offendersin Europe 14Andrew McCallidentifies the positive,practical steps whichneed to be taken toget offendersthroughout Europeback into <strong>employment</strong>.Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e LabourMarkets and SaferCommunities 17Mike Stewart outlinesthe str<strong>at</strong>egic role th<strong>at</strong>Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e LabourMarkets can play inreducing crime andpromoting communitysafety by gettingoffenders into work.Bail or Jail? 20There is anopportunity now to cutthe number ofjuveniles remanded incustody across thecountry in a way whichwill bring benefits tous all, observes KeithTowler.Is Wh<strong>at</strong> Works Wh<strong>at</strong>Counts? 21Unless positive andconstructive measuresto comb<strong>at</strong> localdisorder are developedalongside coercivepowers, argues RobAllen, the currentiniti<strong>at</strong>ive could end uppromoting r<strong>at</strong>her thantackling socialexclusion.Medi<strong>at</strong>ing for a SaferSociety 24Medi<strong>at</strong>ion can help cre<strong>at</strong>esafer communities byreducing crime and thefear of crime, saysStephanie Braithwaite.Legisl<strong>at</strong>ion, Race andCriminal Justice 25Anne Dunn reviews the keyfindings from the Section95 report and looks <strong>at</strong>other legisl<strong>at</strong>ive changeswhich will becomeincreasingly important inthe coming years.ContrastingJudgements 27Wilfred Hyde notes th<strong>at</strong>,judged by the results oftwo intern<strong>at</strong>ionalsentencing seminars,judges in Britain favourlonger prison sentencesthan their continentalcounterparts.REVIEWS page 28Tim B<strong>at</strong>eman reviews ‘TheISTD Handbook ofCommunity Programmes’and ‘A Guide to Setting upand Evalu<strong>at</strong>ingProgrammes for YoungOffenders’.‘AT A GLANCE’ back coverKey points about crimeand the fear of crime fromthe 1998 British CrimeSurvey.SAFER SOCIETY SUBSCRIPTION RATESFull: £20 per year3+ copies: £15 per year per copyOverseas: £30 per yearNACRO members pay just £15 per year - a discount of 25%. If you want to find out moreabout NACRO membership, please contact Carol Hendrickson on 0171 840 6429 or (fax)0171 735 4666NEWS insideThe Government’s greenpaper on measures tosupport families. 5The Government’s whitepaper on improving theprospects of thoseleaving care. 5St<strong>at</strong>istics on children <strong>at</strong>risk. 6Measures to protectchildren <strong>at</strong> risk of sexualabuse. 6Job applicants to be subjectto criminal record checks.6New powers needed fordealing withpsychop<strong>at</strong>hic offenders.6Prob<strong>at</strong>ion hostels workingsuccessfully. 7Home Affairs Committeeargue for gre<strong>at</strong>er use ofcommunity sentences. 7Government welcomesaltern<strong>at</strong>ives to prisonsentences report 7Call for medi<strong>at</strong>ion centresto resolve conflict. 8High level of syringesharing. 8Prisoners are not switchingto heroin. 8Sex offender tre<strong>at</strong>mentprogrammes in prisonsmaking a difference. 8Jack Straw introduces threestrikes law for burglars.8Inspector praises youngoffender institution 9Number of lifers increasing9Do motor projects work? 9The fifth consecutive fall incrime - summary ofrecorded crime andsentencing st<strong>at</strong>istics. 10SAFERSOCIETYEDITORIALBOARDRob AllenMervyn BarrettTim BellSelina CorkeryAnne DunnPenny FraserCraig HarrisBeverley ThompsonFrank WarburtonMelior Whitear

Safer Society FEATUREReintegr<strong>at</strong>ing a LostGener<strong>at</strong>ion,Photo: Frank ManningIn his address <strong>at</strong> the NACRO AnnualGeneral Meeting on 10 November1998Chris MullinMP for Sunderland South and chair ofthe House of Commons Home AffairsSelect Committee, outlined some ofthe background to the Committee’sreport, ‘Altern<strong>at</strong>ives to PrisonSentences’ (published in September),in particular the public’s support forthe ‘prison works’ philosophy.** See News item on page 7Like many of my colleagues, I represent a poor, inner cityconstituency. Through my office pass a long train ofpeople whose lives have been made a misery by crime. Itis perfectly understandable why for many ordinary peoplethe prison works philosophy, however misconceived, has provedso <strong>at</strong>tractive.The 1980s saw the growth of a massive yob culture. It was truein an area like mine and in large parts of the country and Europe.The collapse of work for the unskilled male (in Sunderland welost the shipyards, the coal mines and a lot of our engineeringindustry) meant for a lot of young men - who might once haveleft school <strong>at</strong> the age of 15 or 16, gone into an apprenticeship orsome form of training and started mixing with adults andmoder<strong>at</strong>ing their behaviour accordingly - th<strong>at</strong> their worldchanged completely. When they left school, it was often the lastpublic institution they would have contact with for many yearsunless, as for all too many of them, they came in contact with thecriminal justice system. These young men have frankly causedmayhem in some parts of the country.This is the essential background to the political problem th<strong>at</strong>those of us who want to see the prison popul<strong>at</strong>ion reduced and amore effective criminal justice system have to bear in mind. Inparts of my constituency, civilised life has collapsed. I cannot putit any less dram<strong>at</strong>ically than th<strong>at</strong>. There are whole streets wherethere are very few habitable houses. They have come under<strong>at</strong>tack from gangs of out of control youths.A man came to my surgery a few months ago who has lived onthe Pennywell Est<strong>at</strong>e in Sunderland for 30 years. He said it wasfine when everybody was in work and had useful activities topursue, but eight or nine years ago things began to deterior<strong>at</strong>e. Ihave visited this man several times. He lives in a nicelymaintained ex-council house but the five properties either side ofhim are boarded up and in some cases burnt out. Five propertiesin both directions, and all 10 properties along the back of him.He had made the mistake of buying his council house and as aresult he was trapped. He had a net over his greenhouse to c<strong>at</strong>chin-coming missiles and on the day of his wife’s funeral the carsof the mourners came under <strong>at</strong>tack from youths throwing stones.It is not hard once we put ourselves in his position or th<strong>at</strong> ofsome of his neighbours to understand why the public is not allth<strong>at</strong> receptive to people like myself telling them th<strong>at</strong> prison reallydoes not work and th<strong>at</strong> there must be other options.The other thing th<strong>at</strong> happened during the 1980s and earlier is th<strong>at</strong>the criminal justice system began to lose its way. It became, andNACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 2

Photo: Michael GrieveDiverting the New Gener<strong>at</strong>ionremains so, almost wholly ineffective against certain types of youngoffenders. There was a period as well, and it is passed I am glad to say,when prob<strong>at</strong>ion officers could be heard referring to offenders r<strong>at</strong>her thanthe taxpayer as ‘clients’. Th<strong>at</strong> did not do a lot of good for publicconfidence either. And to compound all th<strong>at</strong>, the police abandoned thepolicing of some of the most difficult areas, like the one I have justdescribed.At the beginning of the 1980s, police officers got very large pay rises.One of the effects of this was th<strong>at</strong>, whereas previously they often livedlocally and were fairly widely dispersed, they all began to get mortgagesand move up to the leafier end of town. I remember a police inspector’swife telling me th<strong>at</strong> there were 13 police officers living in the r<strong>at</strong>hershort street in which she lived. But there was not a single officer on thePennywell Est<strong>at</strong>e, which has about 10,000 people living on it. There wasa time - it has changed now - when the only police officers seen inPennywell came in large raiding parties and glared <strong>at</strong> citizens throughthick plastic windows. Not a very good basis for cre<strong>at</strong>ing communityconfidence. All these factors contributed to a general loss of publicconfidence in the system and a growth in demands for retribution, and itis very difficult for politicians to resist this when they are dailyconfronted with the victims.About five or six years ago some politicians discovered th<strong>at</strong> there werevotes to be had by pursuing the prison works philosophy, even though Isuspect th<strong>at</strong> they knew th<strong>at</strong> it did not. There was a very willingconstituency for this point of view, and the result was an escal<strong>at</strong>ion in theprison popul<strong>at</strong>ion. I like to think th<strong>at</strong> the public<strong>at</strong>ion of our report a fewmonths ago marked the formal end of the prison works philosophy. Wetook evidence from a wide range of witnesses. We had evidence inparticular from two retired senior prob<strong>at</strong>ion officers, Peter Coad andDavid Fraser, and Professor of Criminology Ken Pease. They argued th<strong>at</strong>a much bigger prison popul<strong>at</strong>ion was required; th<strong>at</strong> altern<strong>at</strong>ives do notwork properly and the only way to guarantee th<strong>at</strong> the public is safe fromcriminals is to keep them locked up. But I felt th<strong>at</strong> the bubble burst ontheir argument when they were asked wh<strong>at</strong> level they expected the prisonpopul<strong>at</strong>ion to rise to if their philosophy was to reach its logicalconclusion. They disagreed about numbers but eventually settled onabout 200,000, which was three times the crisis level we have now.I do not think th<strong>at</strong> any government of any political persuasion is able tocontempl<strong>at</strong>e having 200,000 people locked up, if for no other reason thanit is extremely expensive. Once we had on the record th<strong>at</strong> this was wherewe were headed we could have a r<strong>at</strong>ional discussion about thealtern<strong>at</strong>ives.We looked <strong>at</strong> various programmes around the country and the one thingth<strong>at</strong> became clear very quickly was th<strong>at</strong> the outcomes of altern<strong>at</strong>ives toThe second task isto divert thevulnerable awayfrom criminalactivity and intouseful lives. Thisis best done <strong>at</strong> avery young age,long before theycome into contactwith the criminaljustice system.

Safer Society FEATURE Reintegr<strong>at</strong>ing a LostPhoto Michael Grieveprison were not carefully measured. TheChief Inspector of Prob<strong>at</strong>ion told us th<strong>at</strong>of the 230 projects th<strong>at</strong> he hadexamined, only 35 had any crediblemethod of measuring outcomes and ofthose only four were sufficientlyrigorous to hold up to a sceptical public.This is a serious problem and, if wewant to confront the fact th<strong>at</strong> the publicas a whole believes in the prison worksphilosophy, we have to come up withmeasurable evidence th<strong>at</strong> the altern<strong>at</strong>iveswork.It is important, too, th<strong>at</strong> the altern<strong>at</strong>ivesare not seen as soft options by thepublic. My local newspaper regularlyreports th<strong>at</strong> so and so ‘walked free fromcourt’ with ‘only’ 200 hours ofcommunity service. Two hundred hoursof community service, provided it issufficiently rigorous and properlysupervised, is quite a stiff penalty andmight prove to be more demanding thanhaving someone simply sitting in aprison cell, never having to confronttheir offending behaviour. But th<strong>at</strong> is nothow it is perceived or presented. And itis true th<strong>at</strong> many community serviceorders have turned out to be softoptions. When people have not shownup for community service they have notalways been pursued as vigorously asthey might have been and th<strong>at</strong> tooundermines the credibility of the wholesystem. This is an area th<strong>at</strong> I think allthose who care about finding crediblealtern<strong>at</strong>ives to prison have to address. Itis not enough to assert th<strong>at</strong> prison doesnot work. We have to be able todemonstr<strong>at</strong>e this to a sceptical publicand we are some way from this.We have two important tasks. The firstis to do wh<strong>at</strong> we can - and this isdifficult - to reintegr<strong>at</strong>e the lostgener<strong>at</strong>ion of youth, mainly, but not allmales, back into society so th<strong>at</strong> they canhope to lead a purposeful life. In the last18 or 20 years we have been breeding agener<strong>at</strong>ion of alien<strong>at</strong>ed people whon<strong>at</strong>urally are going to behave badly ifthey have no stake in society. Theycannot of course be dealt with bycriminal justice measures alone.Educ<strong>at</strong>ion, training andultim<strong>at</strong>ely work are thekey to success.Educ<strong>at</strong>ion, training and ultim<strong>at</strong>ely work are the key to success. Th<strong>at</strong> is why Welfare toWork was <strong>at</strong> the core of the programme on which this Government was elected.The second task is to divert the vulnerable away from criminal activity and into usefullives. Th<strong>at</strong> is best done <strong>at</strong> a very young age, long before they come into contact with thecriminal justice system. Diversion is absolutely essential if we are to stop anothergener<strong>at</strong>ion of unskilled youth going down the same plug hole as the previous one. Onething I discovered <strong>at</strong> a fairly early stage on the Home Affairs Select Committee is th<strong>at</strong>too much of the Home Office budget goes into locking up people and not enough goesinto diverting vulnerable people before they start offending, even though it is possible toidentify them well in advance.In my constituency we have a very successful scheme called Breakout, which is run bypeople on the Pennywell Est<strong>at</strong>e who during the school holidays organise constructiveactivities for young people. They get some of the parents involved in taking kids to thecountryside and beaches outside Sunderland, which most of the kids have never seen.This scheme, which organises activities on two or three days a week for 700 of the mostvulnerable people initially, costs about £30,000 - the cost of locking up one juvenile fornine months. The moral of the story is clear. If you invest th<strong>at</strong> money <strong>at</strong> a much earlierstage you get a much better result. It is not just a m<strong>at</strong>ter for the criminal justice system.It is about providing a p<strong>at</strong>hway towards work, about nursery educ<strong>at</strong>ion, literacy,numeracy, and proper parenting classes. We have a Government th<strong>at</strong> understands theproblem and is beginning, however inadequ<strong>at</strong>ely, to address it. There is no magicsolution. All we can do is hope to reverse trends th<strong>at</strong> have been set in place over a longtime. I am confident th<strong>at</strong> we can make progress. NACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 4

SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYNewsGovernmentsupportfor familiesMeasures to supportfamilies were outlined ina Government greenpaper, published inNovember. Themeasures include betterservices and support forparents.Measures aimed <strong>at</strong>ensuring th<strong>at</strong> parentshave access to adviceand support includeestablishing theN<strong>at</strong>ional Family andParenting Institute,giving health visitors anew enhanced role,developing the £540million Sure Startiniti<strong>at</strong>ive and familyliteracy and mentoringschemes, andintroducing educ<strong>at</strong>ionfor parenthood inschools.The Sure Startprogramme is aimedparticularly <strong>at</strong> thosefamilies experiencingPhoto: Clare Marsheduc<strong>at</strong>ional underachievement,health,housing, orun<strong>employment</strong>problems. Under it,parents as much aschildren will besupported. Help mayinclude training forwork, help with literacyor numeracy, and helpand advice on disciplineor other parentingproblems.The paper says th<strong>at</strong> ‘byinvesting in Sure Startnow, we will be able tocontinue reaping thebenefits of improvedsocial adjustment andreduced anti-socialbehaviour in 20 years’time, through bettersuccess in <strong>employment</strong>,better health andreduced crime’.Measures also includebetter support forfamilies facing seriousproblems. Here theGovernment hasannounced a new £500million three yearprogramme to cuttruancy, unrulyclassroom behaviourand unnecessaryexclusions in an effortto reduce these by onethirdby 2002.The programme willinvolve close cooper<strong>at</strong>ionbetweenparents, schools and thepolice with more homeschoolliaison,mentoring for difficultpupils and extra staff tofollow up non<strong>at</strong>tendancewithparents.Other areas covered bythe paper concernbetter financial supportfor families, helpingfamilies balance workand home, andstrengthening marriage.SUPPORTING FAMILIES: ACONSULTATION PAPER isavailable from the HomeOffice, 50 Queen Anne’s G<strong>at</strong>e,London SW1H 9ATGovernment to carefor children in careThe Government’s plansfor protecting childrenin care, and forimproving theirprospects when theyleave it, were outlinedin a white paper,‘Modernising SocialServices’, published on30 November. Thepaper followed a socialservices inspector<strong>at</strong>ereport in Septemberwhich found th<strong>at</strong> socialservices were failing toprovide proper care andprotection forvulnerable children andth<strong>at</strong> there were widevari<strong>at</strong>ions in standardsbetween agencies.The white paper notedth<strong>at</strong> children in carehave been abused andneglected by a systemth<strong>at</strong> was supposed tolook after them, andmost leave care with noeduc<strong>at</strong>ionalqualific<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>at</strong> all,many of them <strong>at</strong> gre<strong>at</strong>risk of falling intoun<strong>employment</strong>,homelessness, crimeand prostitution.Action to protectchildren will include theestablishment of a newCriminal Records Bureau(see page 6) to improveand widen access topolice checks onpeople seeking workwith children and othervulnerable people. TheBureau will be a ‘onestopshop’ foremployers wantingaccess to policerecords and thesepar<strong>at</strong>e lists (List 99and the ConsultancyIndex list) maintainedby the Department forEduc<strong>at</strong>ion andEmployment and theDepartment of Health.The paper also sets outthe Government’s plansfor improving socialservices generally. In his response tothe Children’sSafeguard Review,published 4 November,the Secretary of St<strong>at</strong>efor Health, FrankDobson, said th<strong>at</strong> theUtting Report had‘painted a woeful taleof failure. Manychildren who had been“taken into care” toprotect and help themhad not been protectedand helped. Insteadsome had sufferedabuse <strong>at</strong> the hands ofthose who were meantto help them. Manymore had been letdown, never given the<strong>at</strong>tention they needed,shifted from place toplace, school to schooland then turned outwhen they reached 16.’‘The proportion of careleavers aged 16 to 18who leave <strong>at</strong> the age of16 increased from 33%in 1993 to 40% in1997, largely it seems,5 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE NACRO

SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYVulnerablechildren There were 31,600children on childprotection registerson 31 March 1998,according toDepartment of Healthst<strong>at</strong>istics publishedon 29 October. 8,000 (25%) of thechildren on theregisters <strong>at</strong> the endof the year were alsobeing looked after bylocal authorities. According to‘Modernising SocialServices’, in1997/98, 91 childrendied or sufferedserious injury <strong>at</strong> thehands of adultabusers. In someauthorities, as few as25% of young peopleleave care with anyeduc<strong>at</strong>ionalqualific<strong>at</strong>ion. One in fourchildren looked afteraged 14-16 do not<strong>at</strong>tend schoolregularly and manyhave been excludedand have no regulareduc<strong>at</strong>ionalplacement. According to ‘TheSchools’ Census for1998’, there were12,700 permanentexclusions fromprimary, secondaryand special schoolsin 1996/97, anincrease of 2% on theprevious year.as a cost saving measureby local authorities.’This, says the response,‘is alarming. Themajority of ordinaryfamilies continue toprovide a substantialmeasure of support totheir children until theyreach <strong>at</strong> least 18; theaverage age <strong>at</strong> whichyoung people now leavehome for independenceis estim<strong>at</strong>ed to be 22.Moreover, care leaversare likely to be r<strong>at</strong>hermore dependent thanothers <strong>at</strong> th<strong>at</strong> age inview of their personaland educ<strong>at</strong>ionalhistories.’ TheGovernment iscommitted to reversingthis trend. Research on ‘Caringfor Children Away fromHome’, published on 18November, confirmeddoubts about theefficacy of some parts ofthe residential sector.Two-fifths of the childrenin residence say theyhave been bullied in therecent past; one in sevensay they have beentaken advantage ofsexually by anotherresident; two-thirds saythey have been unhappyin the recent past andtwo-fifths say they havecontempl<strong>at</strong>ed suicide.The report containsrecommend<strong>at</strong>ions toimprove standards andtackle abuse in children’shomes.MODERNISING SOCIAL SERVICES:PROMOTING INDEPENDENCE,IMPROVING PROTECTION, RAISINGSTANDARDS is available from TheSt<strong>at</strong>ionery Office. Price £14.50and on the Internet on:http\\www.officialdocuments.co.uk\document\cm41\4169\4169.htmAn Executive Summary isavailable free from theDepartment of Health, PO Box410, Wetherby, West YorkshireLS23 7LN. The summary and a A5popular version are on theInternet on:http\\www.doh.gov.uk\scg\wpaper.htmTHE GOVERNMENT’S RESPONSETO THE CHILDREN’S SAFEGUARDREVIEW is available from TheSt<strong>at</strong>ionery Office. Price £4.50.CARING FOR CHILDREN AWAYFROM HOME - MESSAGES FROMRESEARCH is available from JohnWiley and Sons. Price £13.99.Child prostitutesto be tre<strong>at</strong>edas victimsChild prostitutes will betre<strong>at</strong>ed as victims ofabuse under joint HomeOffice and Departmentof Health guidance,published on 29December. The guidanceaims to: safeguard andpromote the welfare ofthe children; encouragethe investig<strong>at</strong>ion andprosecution of criminalactivities by those whoabuse and coercechildren in prostitution;and establish th<strong>at</strong> theprimary lawenforcement effort mustbe against abusers andcoercers. The Governmentpublished the SexualOffences (Amendment)Bill on 17 December tocre<strong>at</strong>e a new offence ofabuse of trust, whichwill apply where aperson aged 18 or over,in specifiedcircumstances, hassexual intercourse orengages in any othersexual activity with ortowards a person underth<strong>at</strong> age, if the olderperson is in a positionof trust over theyounger person.The offence is intendedto protect 16 and 17year olds in potentiallyvulnerablecircumstances,including detention orresidential care, orwhere the rel<strong>at</strong>ionshipof trust is particularlystrong, such as inschools.The Bill also equalisesthe age of consent forhomosexuals from 18 to16 in England, Walesand Scotland (and 17 inNorthern Ireland).Criminalrecord checksannouncedThe Governmentannounced plans on 14December 1998 toimplement Part V of thePolice Act 1997 whichwill mean th<strong>at</strong> allemployers will be ableto obtain the records ofjob applicants. Underthe Act, a CriminalRecords Bureau will beestablished inMerseyside under themanagement of theUnited KingdomPassport Agency. Thecore work of examiningrecords and issuingcertific<strong>at</strong>es will behandled by civilservants.This will take about twoyears to set up. Onceestablished, allemployers will be ableto find out whether jobapplicants have acriminal record, eitherby requiring theapplicants to run acheck on themselves or,in some instances, byrunning the checkdirectly.The Bureau will be selffinancing.All applicantsfor certific<strong>at</strong>es from theagency will be requiredto pay a fee which theGovernment estim<strong>at</strong>eswill vary from between£5 and £10.The Government willphase in checks. Prioritywill be given to theissue of certific<strong>at</strong>es forNACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 6

SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYthose seeking positionswhich involve regularlycaring for, training,supervising or being insole charge of personsunder 18.Psychop<strong>at</strong>hicoffenders: newpowers neededNew legal powers areneeded to protect thepublic from offenderssuffering frompsychop<strong>at</strong>hic disordersand to care for them,according to a reportpublished by NACRO on4 November 1998.The report, ‘Risks andRights’, calls for a newreviewable sentence fordangerous offenderswith a psychop<strong>at</strong>hicdisorder who have beenconvicted of a seriousviolent or sexualoffence. At presentmany such offenders goto prison because thecourts are told bypsychi<strong>at</strong>rists th<strong>at</strong> theoffender is untre<strong>at</strong>able,while others are givenhospital orders. Thereport says th<strong>at</strong>‘psychi<strong>at</strong>rists disagreeabout tre<strong>at</strong>ability andwhether an offenderends up in prison orhospital can be a m<strong>at</strong>terof chance’.The report proposesth<strong>at</strong> offenders given thenew sentence wouldinstead be placed insepar<strong>at</strong>eaccommod<strong>at</strong>ion outsidethe current penal andhealth systems, with apositive approachaiming <strong>at</strong> rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion.Had such a power andback up arrangementsbeen available, moreeffective and earlierintervention might havebeen possible in thecase of Michael Stone,convicted of the murderof Lynn and MeganRussell.The report stresses th<strong>at</strong>the gre<strong>at</strong> majority ofmentally disturbedpeople do not present adanger to others andth<strong>at</strong> the current legalframework for dealingwith people with asevere mental illness -as opposed to thosewith a psychop<strong>at</strong>hicdisorder - is adequ<strong>at</strong>e. Itargues, however, th<strong>at</strong>minimising the riskassoci<strong>at</strong>ed with severemental illness requiresmuch better fundedcommunity care, withswift access to back-upspecialist and hospitalservices.The report recommendscloser and better coordin<strong>at</strong>edcontact byagencies working withvulnerable mentallydisturbed people tomake sure th<strong>at</strong> they arecared for and th<strong>at</strong>urgent action is taken iftheir condition worsens.It calls for a code ofpractice on managingrisk for all agenciesdealing with mentallydisturbed people.RISKS AND RIGHTS: MENTALLYDISTURBED OFFENDERS ANDPUBLIC PROTECTION isavailable from NACRO. Price£11 including postage.Prob<strong>at</strong>ion hostelsgiven vote ofconfidenceBail and prob<strong>at</strong>ionhostels areunquestionablydemonstr<strong>at</strong>ing theirability to accommod<strong>at</strong>eand work successfullywith some of the mostdifficult, damaged andpotentially dangerousdefendants andoffenders, according toa prob<strong>at</strong>ion inspector<strong>at</strong>ereport published on 3November 1998.The report, ‘Deliveringan Enhanced Level ofCommunity Supervision’,found th<strong>at</strong> in 1997, 67%of orders or conditionsof residence weresuccessfully completed.Less than 4% ofresidents in the hostelscovered by theinspection were knownto have been chargedwith an offencecommitted during theirresidence, and themajority of these wereof a rel<strong>at</strong>ively minorn<strong>at</strong>ure. The public‘should takeencouragement fromthese findings’.DELIVERING AN ENHANCEDLEVEL OF COMMUNITYSUPERVISION: REPORT OF ATHEMATIC INSPECTION ON THEWORK OF APPROVEDPROBATION AND BAIL HOSTELSis available from the HomeOffice.Rising prisonpopul<strong>at</strong>ion‘unsustainable’In its report on‘Altern<strong>at</strong>ives to PrisonSentences’, published on10 September, the HomeAffairs Committeehighlighted a number ofprogrammes which<strong>at</strong>tempt to divert youngpeople away from crime.These include SherborneHouse in South London,which deals with youngmale offenders whowould otherwise havereceived a custodialsentence. Theseparticipants have areconviction r<strong>at</strong>e 15%lower than would bepredicted for suchoffenders.But the Committee notesthe ‘absence of rigorousresearch into theeffectiveness ofindividual communitysentences <strong>at</strong> present,and th<strong>at</strong>, until this isrectified, confidence inthem must be limited,and sentencing policy am<strong>at</strong>ter of guessworkand optimism’.Nevertheless, notingth<strong>at</strong> the current risingprison popul<strong>at</strong>ion is‘unsustainable’, theCommittee concludesth<strong>at</strong> ‘there are manypeople currentlysentenced toimprisonment who couldbe dealt with moreeffectively - and <strong>at</strong> farless expense - by a noncustodialsentence’.Among diversionaryschemes, it highlightsYouthWorks inBlackburn, one of fiveYouthWorks initi<strong>at</strong>ivesaimed <strong>at</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ing ‘safer,high-qualityenvironments byharnessing the energiesof young people in aproductive way’.YouthWorks appears tobe achieving its aim ofreducing crime in theRoman Road Est<strong>at</strong>e areaof Blackburn, which wasnumber one in a rankingof police be<strong>at</strong>s in termsof crime committed andnow is number 14.The Committeecommend such schemesbut note th<strong>at</strong> theirfunding is err<strong>at</strong>ic. ‘Theprecarious financialsitu<strong>at</strong>ion such projectsfind themselves inmakes it difficult tomake long-term plansand takes up thevaluable time of theirworkers which could bemore usefully spent withthe young peopleconcerned ... The costeffectivenessof suchschemes is difficult toquantify and impossibleto ignore.’ALTERNATIVES TO PRISONSENTENCES: THIRD REPORT OFTHE HOME AFFAIRSCOMMITTEE SESSION 1997-98is available from The St<strong>at</strong>ioneryOffice. Price £11.50.Government7 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE NACRO

SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYwelcomes MPs’reportIn a reply published inDecember, theGovernment welcomedthe Home AffairsCommittee’s report on‘Altern<strong>at</strong>ives to PrisonSentences’.‘We believe th<strong>at</strong> thecourts should haveavailable to them aneffective range ofsentencing options andthe Committee’s reportcontributes to realisingth<strong>at</strong> aim’, st<strong>at</strong>es thereply. It points out th<strong>at</strong>the introduction of thehome detention curfewis expected to cause afall in the prisonpopul<strong>at</strong>ion from justunder 66,000 in l<strong>at</strong>e1998 to an average of63,200 in 1999.‘Imprisonment must bethe right response forthose who havecommitted seriousoffences, for those whopose a danger to thepublic, such as violentand sexual offendersand for persistentoffenders. However …there are manyoffenders whose crimescan adequ<strong>at</strong>ely bepunished by fines or bycommunity penalties,providing th<strong>at</strong> thosepunishments arerealistic and arerigorously enforced.’A further £127 millionof government fundingis being provided forthe prob<strong>at</strong>ion serviceover the next threeyears, and the Crimeand Disorder Act 1998‘introduces tough newcommunity orderswhich will fill specificgaps within the optionscurrently available tosentencers’.Describing the HomeAffairs Committee’sreport as ‘useful andconstructive’, the paperconcludes: ‘TheGovernment intends th<strong>at</strong>sentencers and thepublic should regardcommunity sentences astough and effectivepunishments for manyoffences and th<strong>at</strong> prisonis used only whennecessary.’THE GOVERNMENT REPLY TOTHE THIRD REPORT FROM THEHOME AFFAIRS COMMITTEESESSION 1997-98 ‘ALTERNATIVESTO PRISON SENTENCES’, isavailable from The St<strong>at</strong>ioneryOffice, £5.20.Medi<strong>at</strong>ion’s role intackling conflictThe Home Office shoulduse funds from its crimereduction str<strong>at</strong>egy toestablish and evalu<strong>at</strong>eproperly resourcedmedi<strong>at</strong>ion centres in 12major cities, says areport on NACRO’smedi<strong>at</strong>ion schemespublished on 25 January.The report, ‘ReducingConflict, BuildingCommunities’, arguesth<strong>at</strong> medi<strong>at</strong>ion canresolve conflicts beforethey escal<strong>at</strong>e out ofcontrol. For example, 80to 90% of conflictsbetween feudingneighbours which resultin face-to-face medi<strong>at</strong>ionare resolved.And <strong>at</strong> around £300 acase, medi<strong>at</strong>ion is muchcheaper thantransferring or evicting <strong>at</strong>enant. The report alsocalls for the gre<strong>at</strong>er useof victim-offendermedi<strong>at</strong>ion. Many victimsfind confronting theoffender is valuable incoming to terms withcrime and most of themwho do are happy withthe outcome.Medi<strong>at</strong>ion can also be aneffective means ofreducing reoffending bymaking offendersappreci<strong>at</strong>e the harm theyhave caused. In onesurvey, two-thirds ofoffenders who took partin medi<strong>at</strong>ion sessions inLeeds did not re-offend,despite most of thembeing persistentoffenders.REDUCING CONFLICT, BUILDINGCOMMUNITIES: THE ROLE OFMEDIATION IN TACKLING CRIMEAND DISORDER is availablefrom NACRO. Price £3.50including postage. See alsofe<strong>at</strong>ure on Medi<strong>at</strong>ion on page24.Drug users sharingequipmentA survey of injectingdrug users not incontact with drugtre<strong>at</strong>ment services foundth<strong>at</strong> three-quarters ofthem (78%) had sharedequipment during thefour weeks prior tointerview. The survey,published on 9December by theImperial College Schoolof Medicine, said th<strong>at</strong>the level of sharing ofsyringes is much higherthan has been found inprevious studies. According to theDepartment of Health’s‘Drug Misuse St<strong>at</strong>istics’,21,996 drug misuserspresented themselves todrug misuse services inthe six months ending30 September 1997.Over half (54%) were intheir twenties andaround one in eight(13%) were aged under20.Over half (54%) of themisusers were onheroin. Others were onmethadone (13%),amphetamines (9%) orcannabis (9%). Of the estim<strong>at</strong>ed £1.4billion spent on antidrugactivities in1997/98, 12% was spenton prevention (includingeduc<strong>at</strong>ion) and 13% wasspent on tre<strong>at</strong>ment andrehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion, accordingto Dr Jack Cunninghamin a parliamentaryanswer to AnnWinterton, MP, on 18November. Similar levelsof expenditure areexpected in 1998/99. On 17 November, theStanding Conference onDrug Abuse launchedits new directory forthose seeking help fordrug misuse. Thedirectory, ‘DrugProblems - Where to GetHelp’ lists over 500services around Englandand Wales.Few prisonersswitching to heroinAccording to a HomeOffice report, contraryto the view th<strong>at</strong> themand<strong>at</strong>ory drug-testingprogramme mightencourage prisoners tochange from cannabisto heroin because thel<strong>at</strong>ter is less easilydetectable in tests, veryfew prisoners havemade the change andnone are becomingpermanent heroin users.The Home Office reportalso estim<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> thecost of the programmein terms of extra daysspent in custody bypeople failing the testsis £7 million.MANDATORY DRUG TESTINGIN PRISONS: THERELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MDTAND THE LEVEL AND NATUREOF DRUG MISUSE, ResearchStudy No.189, is availablefrom the Home Office.Prison programmesworkingAn evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of the sexoffender tre<strong>at</strong>mentprogramme in sixprisons shows th<strong>at</strong> theywere successful inincreasing the level ofchild abusers’admittance of offendingbehaviour. Pro-offending<strong>at</strong>titudes, such asthoughts about havingNACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 8

SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYsexual contact withchildren, were reducedas were levels of thedenial of the impactth<strong>at</strong> sexual abuse hasupon victims.Overall the programmeswere successful <strong>at</strong>increasing levels ofsocial competence. Ofthe sample, 67% (53 outof 77 men) were judgedto have shown <strong>at</strong>re<strong>at</strong>ment effect - therewere significantchanges in all or someof the main areastargeted. Longer-termtre<strong>at</strong>ment (about 160hours) produced resultswhich held up betterafter release than shorttermtherapy (about 80hours), particularly forhighly deviantoffenders. A 1995/96 PrisonService study on theeffectiveness of prisonregimes showed th<strong>at</strong>particip<strong>at</strong>ion oneduc<strong>at</strong>ional/voc<strong>at</strong>ionalcourses reduced ther<strong>at</strong>es of reconvictionprovided th<strong>at</strong> they wereundertaken by offenderswho had a need in th<strong>at</strong>area, according toGeorge Howarth in aparliamentary answer toJim Cunningham, MP, on17 December. About 3,000prisoners are expectedto complete accreditedoffending behaviour andsex offender tre<strong>at</strong>mentprogrammes during1998/99, according toLord Williams in aparliamentary answer toLord Avebury on 16December.AN EVALUATION OF THEPRISON SEX OFFENDERTREATMENT PROGRAMME,Research Findings No.79, isavailable from the HomeOffice.Crime (Sentences)ActOn 13 January 1999, theHome Secretary, JackStraw, announced hisintention to implementsection 4 of the Crime(Sentences) Act prescribinga minimum sentence ofthree years for a thirdoffence of domesticburglary. This will takeeffect from December.The announcementfollowed a Court of Appealjudgement, delivered on 15December 1998,concerning section 2 of theAct. Section 2 provides th<strong>at</strong>where an offender over 17is convicted for a secondtime of a serious sexual orviolent offence the courtmust pass a life sentenceunless there are‘exceptional circumstances’which justify it not doingso.The Court of Appeal hasnow laid down th<strong>at</strong>, wherea life sentence is passedunder section 2, the tariffperiod - the period to beserved for the purposes ofdeterrence and retribution(after which prisoners canbe considered for releaseon licence) - shouldnormally be about one halfof the determin<strong>at</strong>esentence which the courtwould have imposed had itnot been required to passa life sentence.Thus the judgement makesclear th<strong>at</strong> the courts retaina substantial measure ofdiscretion in influencingwh<strong>at</strong> happens to aprisoner even though thelife sentence itself ismand<strong>at</strong>ory. It alsosuggests th<strong>at</strong> section 2may, taken alone, have aless dram<strong>at</strong>ic effect on thesize of the prisonpopul<strong>at</strong>ion than mighthave been assumed.Prisons Inspectorpraises ThornCrossThe Chief Inspector of Prisons, SirDavid Ramsbotham, praised the HighIntensity Training Unit <strong>at</strong> Thorn Crossyoung offender institution in aninspection report published inJanuary.Wh<strong>at</strong> works?Motor projectsPhoto: Clare Marsh According to ‘Motor Projects’, 80% of the 1,087offenders who <strong>at</strong>tended 42 motor projects between1989 and 1993 were reconvicted within two years.Three-quarters of these were reconvicted for motoringoffences. Such a high level of reconviction may not besurprising. Despite the rel<strong>at</strong>ive youth of the sample,many offenders had extensive criminal histories. 26%had more than 10 previous convictions, 56% hadmore than six convictions, and 95% had previousconvictions. Overall, however, the 80% of offenders who werereconvicted, were reconvicted of less seriousoffences. The most common motoring reconvictionswere driving while disqualified (49%), driving withoutinsurance (48%), and taking a vehicle without consent(21%). And while the actual reconviction r<strong>at</strong>es were higherthan predicted with particularly poor results for‘racing’ projects, the actual reconviction r<strong>at</strong>es forolder offenders on the projects were lower thanpredicted (6% lower). In addition, those who completed programmesfared better than those who did not: offenders whodid not complete the projects were reconvicted <strong>at</strong>much higher r<strong>at</strong>es than their age and criminalhistories would suggest. In its report on ‘Altern<strong>at</strong>ives to Prison Sentences’,the Home Affairs Committee noted th<strong>at</strong> research intothe Ilderton Motor Project, conducted by the InnerLondon Prob<strong>at</strong>ion Service, found th<strong>at</strong> the reconvictionr<strong>at</strong>e of project <strong>at</strong>tenders over three years was 38%lower than th<strong>at</strong> of a similar group. It also noted th<strong>at</strong> participants on the MerseysideService’s Car Offender Project were found to have a24% reconviction r<strong>at</strong>e over a 12 month follow-upperiod, compared to a 43% reconviction r<strong>at</strong>e for suchoffenders n<strong>at</strong>ionally.MOTOR PROJECTS IN ENGLAND AND WALES: AN EVALUATION, HomeOffice Research Findings No.81, is available from the Home Office,50 Queen Anne’s G<strong>at</strong>e, London SW1H 9AT. Free. ALTERNATIVES TOPRISON SENTENCES: THIRD REPORT OF THE HOME AFFAIRSCOMMITTEE SESSION 1997-98 is available from The St<strong>at</strong>ioneryOffice. Price £11.50.9 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY

Criminal St<strong>at</strong>istics1997Crime r<strong>at</strong>esIn 1997, 4.6 million notifiable offenceswere recorded by the police in England andWales, 6% fewer than in 1996 - the fifthconsecutive annual fall, the first occurrencethis century. Nevertheless, the number ofnotifiable offences recorded by the policeper 100,000 popul<strong>at</strong>ion has risen from1,100 in 1950 to 8,600 in 1997.Comparison of British Crime Surveyestim<strong>at</strong>es of crime committed (see backcover) with police recorded crime revealsth<strong>at</strong> there were: over three times as manydomestic burglaries committed as recorded;over three times as many woundings;nearly four times as many bicycle thefts;four times as many thefts from vehicles;nearly seven times as many offences ofvandalism; and eight times as manyrobberies and thefts from the person.17% of recorded offences resulted insomeone being charged, summoned orcautioned. 11% of offences were ‘taken intoconsider<strong>at</strong>ion’ or resulted in ‘no furtheraction’.Nearly all the countries of Western Europehave shown a sharp increase in recordedcrime between 1987 and 1997 withEngland and Wales experiencing an increaseof 18%, about average for Western Europe.However, the recent sharp fall in Englandand Wales contrasts with many othercountries where recorded crime is stillrising.HomicideNearly two-thirds of the 738 victims ofhomicide in 1997 were males.Women were more likely to be strangledor asphyxi<strong>at</strong>ed (25% were) than men (3%).Men were most likely to have been killedwith a sharp instrument (32%). Firearmswere used in 9% of all homicides.The main suspect was someone knownto half of male victims and three-quartersof female victims.Children under a year old were most <strong>at</strong>risk of homicide.One person convicted of homicide in1997 had been convicted of homicideon a previous occasion. One otherperson who had been previouslyconvicted of homicide committedsuicide after committing homicide in1997.SAFER SOCIETY NEWS SAFER SOCIETYOffendersIn total, 1.7 million offenders were found guilty or cautioned in1997, including 509,400 found guilty or cautioned for indictableoffences:Offenders cautioned or found guilty in 1997Indictable offence(000s)Violence against the person 58.2Sexual offences 6.4Burglary 41.1Robbery 6.2Theft and handling stolen goods 201.2Fraud and forgery 24.2Criminal damage 13.3Drug offences 96.7Other (excluding motoring offences) 52.6Motoring offences 9.5Total 509.4The peak age of ‘known’ offending is now 18 for both males andfemales.Sentencing93,100 offenders were sentenced to immedi<strong>at</strong>e imprisonment, 9%more than in 1996 and the highest figure since <strong>at</strong> least 1928:Offenders sentenced in 1997 by sentence or orderSentence or order(000s)Discharge 128.0Fine 998.7Prob<strong>at</strong>ion order 54.1Supervision order 11.2Community service order 47.1Attendance centre order 7.6Combin<strong>at</strong>ion order 19.5Curfew order 0.4Total community sentences 140.0Fully suspended imprisonment 3.5Young offender institution 22.1Unsuspended imprisonment 71.0S.53 C&YP Act 1933 0.7Total immedi<strong>at</strong>e custody 93.1Otherwise dealt with 20.7Total 1,384.7At magistr<strong>at</strong>es’ courts, immedi<strong>at</strong>e custody was imposed for 11% ofindictable offenders, compared with 4-5% in 1989 to 1992.At the Crown Court, use of immedi<strong>at</strong>e custody for indictable offencesrose from 43% in 1990 to 60% in 1996 - the highest recorded figuresince the early 1950s - and remained <strong>at</strong> th<strong>at</strong> level in 1997.The prison popul<strong>at</strong>ion in England and Wales rose by just under one-thirdbetween 1987 and 1997 compared with a doubling in the Netherlandsand the USA and a reduction of about one-third in Finland.CRIMINAL STATISTICS ENGLAND AND WALES 1997 is available fromThe St<strong>at</strong>ionery Office. Price £22.40.NACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 10

Safety Society FEATURESafety ThroughRegener<strong>at</strong>ionCutting Crime byTackling Depriv<strong>at</strong>ionBY ROB ALLEN‘In my own garageI found a spotwhere kids hadbroken in, huddledround blanketsand sniffed glue.There is no excusefor drug abuse orlaw breaking butthese kids have aright to expectbetter and weought to offerthem better.’John Prescott,Deputy PrimeMinisterTurning around the worst est<strong>at</strong>es in Britain is among the most difficult tasks facing theGovernment. In several thousand neighbourhoods high-crime r<strong>at</strong>es are but one symptom of arange of social problems. Poor health, housing and educ<strong>at</strong>ion and above all a lack of legitim<strong>at</strong>ework opportunities combine to produce troubled and troublesome communities whose quality of lifeshames an affluent country <strong>at</strong> the end of the 20th century.NACRO’s 1995 report on ‘Crime and Social Policy’ identified the fact th<strong>at</strong> the hardships associ<strong>at</strong>edwith gre<strong>at</strong>er inequality were being concentr<strong>at</strong>ed in certain neighbourhoods where crime and disorderwere much more prevalent (NACRO, 1995). It argued th<strong>at</strong> crime is not only linked with destabilised,demoralised and marginalised communities, but it contributes to their decline. As the Americans Kellingand Coles put it in their influential book ‘Fixing Broken Windows’, ‘ultim<strong>at</strong>ely the result for aneighbourhood whose fabric or urban life and social intercourse has been undermined is increasingvulnerability to an influx of more disorderly behaviour and serious crime’ (Ref).The ‘Crime and Social Policy’ report recommended targeting crime prevention resources towards suchareas and argued th<strong>at</strong> ‘action must be linked with other str<strong>at</strong>egies to deal with this depth of disadvantage... Local efforts need support from a broader n<strong>at</strong>ional str<strong>at</strong>egy for economic and social regener<strong>at</strong>ionwhich recognises the impact of social and economic policies. Central to all of this will be theinvolvement and commitment of local people.’The Government’s commitment to do something about the poorest areas is therefore welcome and iftransl<strong>at</strong>ed into successful action on the ground could make a huge impact on crime. The recipe forsorting out the problems is contained in the third report of its Social Exclusion Unit (SEU), published inSeptember to coincide with the launch of the New Deal for Communities (NDC) funding programme.The report, ‘Bringing Britain Together’, is a wide-ranging analysis of the problems and the lessons fromprevious efforts to solve them (SEU, 1998). The report sets out the components of a comprehensive newn<strong>at</strong>ional str<strong>at</strong>egy. The str<strong>at</strong>egy, which reflects closely much in the ‘Crime and Social Policy’ report,comprises three strands: the first is made up of the range of initi<strong>at</strong>ives already being undertaken byindividual departments, such as the various New Deals and policies on failing schools, healthimprovement and crime and disorder reduction.Second is the New Deal for Communities, with its emphasis on funding long-term measures which aredeveloped and managed very locally, involve local people and integr<strong>at</strong>e the work of differentprofessionals, agencies and organis<strong>at</strong>ions. Initially targeted on 17 p<strong>at</strong>hfinder areas, NDC will eventuallyspend £800 million.11 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE NACRO

Tony Blair meetsworkers on the HollyStreet est<strong>at</strong>e in eastLondon <strong>at</strong> the launch ofNew Deal forCommunities, 15Photo: Evening StandardThird, the Government has cre<strong>at</strong>ed 18 cross-cutting action teamsof civil servants and outside experts to draw up plans fortackling underlying problems of regener<strong>at</strong>ing local economies,improving housing and neighbourhood management, enhancingprospects for young people, increasing access to high-qualityservices and making the Government work better.Among a wide range of questions, the teams will be consideringhow best to get the most disadvantaged people into work,prevent anti-social behaviour, build and support communityorganis<strong>at</strong>ions, involve parents in their children’s educ<strong>at</strong>ion,engage people in poor neighbourhoods in arts, sport and leisure,and reduce youth disaffection. More ambitiously still, teams willbe asking how shops, insurance and financial services can beencouraged back into poor neighbourhoods, along with capital tostimul<strong>at</strong>e business start-ups.There is no faulting the breadth and ambition of the str<strong>at</strong>egy,although the true test as always will be whether the army ofstakeholders <strong>at</strong> central and local level will be able to ‘walk thewalk’ as well as ‘talk the talk’. The flavour of the analysis isfamiliar from earlier SEU reports on truancy and exclusion andon rough sleeping, which emphasised the importance of morejoined-up government and better inter-agency co-oper<strong>at</strong>ion, quiteas much as the need for more resources.Perhaps the most innov<strong>at</strong>ive idea is th<strong>at</strong> all of the local authorityand other public agencies providing services to a community -social services, health, housing and police - work in multidisciplinaryteams under a ‘neighbourhood manager’. As well asovercoming the fragment<strong>at</strong>ion of different schemes andprogrammes often going on in the same area - wh<strong>at</strong> the SEUcalls ‘initi<strong>at</strong>ive-itis’ - neighbourhood management, throughaccountability to a neighbourhood board and the development ofa local plan, should enable problems to be addressed in a moreholistic way and for resources to be shared in a much moreplanned way.Wh<strong>at</strong> are the key issues which will determine the success orfailure of the l<strong>at</strong>est in a long line of initi<strong>at</strong>ives? First, the extentto which the new partnerships genuinely engage local peoplewill be crucial. Tony Giddens in ‘The Third Way’ argues th<strong>at</strong> ‘inorder to work, partnerships between government agencies, thecriminal justice system, local associ<strong>at</strong>ions and communityorganis<strong>at</strong>ions have to be inclusive - all economic and ethnicgroups must be involved’ (Giddens, 1998). Wh<strong>at</strong> this analysisignores is the often highly divided n<strong>at</strong>ure of the mostdisadvantaged communities.Forthcoming research by NACRO into social crime preventionmeasures in two northern cities shows the importance ofproactive efforts to involve and engage local people - the young,the isol<strong>at</strong>ed, victims of crime and offenders - but achievinggenuinely inclusive consult<strong>at</strong>ion and particip<strong>at</strong>ion is a prizeworth having. NACRO’s Huyton Community Crime Preventionproject, which has been funded by the Single Regener<strong>at</strong>ionBudget in Merseyside, will try to put the lessons of this researchinto action.The carrot of funding will help in the NDC areas, but elsewherecommunity involvement will not just happen. Indeed the rolewhich it is envisaged th<strong>at</strong> the police will play will not beuniversally welcomed. While the idea put forward by Giddensth<strong>at</strong> the police ‘should work closely with citizens to improvelocal community standards and civil behaviour using educ<strong>at</strong>ion,persuasion and counselling instead of arraignment’ is muchpreferable to using their powers to sweep undesirables off thestreets, it will need to be implemented thoughtfully.Second, the SEU report places gre<strong>at</strong> faith in the ability both ofNACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 12

Safety Through Regener<strong>at</strong>ion FEATURE Safer Societyagencies to work more effectively <strong>at</strong> thecoalface and of mainstream government policiesto develop a more preventive focus targeted onthe worst problems. Another NACRO researchstudy due to be published shortly, evalu<strong>at</strong>ing thecommunity safety str<strong>at</strong>egy of a large city,revealed the difficulties of meaningfullycoordin<strong>at</strong>ing the work of departments within asingle local authority let alone across the wideragency landscape. Signing up to plans orprotocols is one thing, changing the direction ofday to day work and above all spending moneydifferently can be quite another.Efforts to bring about better inter-agencyworking with young offenders is being drivenforward by new st<strong>at</strong>utory infrastructure in theform of youth offending teams and a YouthJustice Board, together with a frameworkdocument setting out wh<strong>at</strong> it means in practicefor different agencies to give effect to thest<strong>at</strong>utory aim of preventing offending by youngpeople. Something similar may be required ifthe neighbourhood management provessuccessful in the p<strong>at</strong>hfinder areas. It willcertainly be important for neighbourhoodrenewal initi<strong>at</strong>ives to be linked into the crimeand disorder reduction str<strong>at</strong>egies which will bein place from 1st April.As for central government policy, it will beimportant for the action teams to grasp somepotentially painful nettles. Businessimprovement districts could offer tax breaks forcorpor<strong>at</strong>ions which particip<strong>at</strong>e in str<strong>at</strong>egicplanning and invest in design<strong>at</strong>ed areas.Mainstream schools must be properly equippedand resourced to educ<strong>at</strong>e the most troublesomeyoungsters r<strong>at</strong>her than given the opportunity tooff-load them into special units. And housingauthorities must not be allowed simply to ridtheir own properties of anti-social or difficulttenants <strong>at</strong> the expense of the wider community.More contentious still is the question of drugs.In all too many of the poorest areas theconsumption, distribution and exchange of drugshas filled the space vac<strong>at</strong>ed by work in the livesof residents. While the Government haseffectively ruled out the policy ofdecriminalis<strong>at</strong>ion favoured by radicalcomment<strong>at</strong>ors, it is clear th<strong>at</strong> unless educ<strong>at</strong>ion,prevention and tre<strong>at</strong>ment programmes areintroduced on a scale to m<strong>at</strong>ch the problem,efforts <strong>at</strong> renewal will struggle.Getting central departments and the localagencies they sponsor to take a broad andinclusive view of their social role andresponsibilities is the key task.Nowhere is this more true than when dealingwith the people who do offend or engage in antisocialbehaviour. The consequences of moreaggressive use of powers to evict and of theanti-social behaviour order, spelled out by TimBell in the last issue of ‘Safer Society’, couldlead to an ‘unhouseable’ underclass ofpermanently excluded people. Theimplement<strong>at</strong>ion of criminal convictioncertific<strong>at</strong>es in the Police Act 1997 could make ita good deal more difficult for people with acriminal record to find legitim<strong>at</strong>e work. Properconcern to prevent dangerous sex offenders fromworking with children is thre<strong>at</strong>ening to spill overinto <strong>at</strong> best a wariness of, <strong>at</strong> worst an outrightrefusal to consider, a much wider range ofoffenders for a much wider range of work whichthey could quite properly do.Helping offenders to get and keep a job isperhaps the best way of preventing re-offending.As well as improving the quality and extent ofwork-based training, there is a need to ensureth<strong>at</strong> offenders are not increasingly excludedfrom opportunities. The Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e LabourMarket initi<strong>at</strong>ives described by Mike Stewart(page 17) have particular promise in the mostdisadvantaged areas.NACRO’s forthcoming campaign, ‘GoingStraight to Work’, will seek to encourageemployers of all kinds not to write offoffenders*. This is part of a much larger task ofensuring th<strong>at</strong>, to adapt the objectives of theHome Office, society is just and tolerant as wellas safe. It is with all three objectives in mindth<strong>at</strong> the str<strong>at</strong>egy for neighbourhood renewalmust be implemented. * An article about the campaign will be included inthe next issue.ReferenceGiddens, A (1998), ‘The Third Way’, Polity PressKelling, G L and Coles, C M (1977), ‘Fixing BrokenWindows’, Simon and SchusterNACRO (1995), ‘Crime and Social Policy: A Report ofthe Crime and Social Policy Committee’Social Exclusion Unit (1998), ‘Bringing BritainTogether: A N<strong>at</strong>ional Str<strong>at</strong>egy for NeighbourhoodRenewal’.As for centralgovernment policy, itwill be important forthe action teams tograsp some difficultnettles. Businessimprovement districtscould offer tax breaksfor corpor<strong>at</strong>ions whichparticip<strong>at</strong>e in str<strong>at</strong>egicplanning and invest indesign<strong>at</strong>ed areas.Mainstream schoolsmust be properlyequipped andresourced to educ<strong>at</strong>ethe most troublesomeyoungsters r<strong>at</strong>her thangiven the opportunityto off-load them intospecial units. Andhousing authoritiesmust not be allowedsimply to rid their ownproperties of antisocialor difficulttenants <strong>at</strong> the expenseof the widercommunity.ROB ALLENIS NACRO’s DIRECTOR OFRESEARCH ANDDEVELOPMENT13 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE NACRO

LOOKING AT EMPLOYMENTEmploying Offendersin EuropeBY ANDREW McCALLIn five years working for theEuropean Offender EmploymentForum, I have come into contact withministers, European commissioners,members of n<strong>at</strong>ional and Europeanparliaments, government officials,eminent academics and projectworkers. Almost without exception,they have identified a close linkbetween un<strong>employment</strong>, offending,re-offending and rising crime. Noonedisputes th<strong>at</strong> reintegr<strong>at</strong>ingoffenders through <strong>employment</strong> isbeneficial. This consensus, however,has failed to transl<strong>at</strong>e itself intopractical, effective and co-ordin<strong>at</strong>edaction across Europe. Why is this?The European Offender EmploymentForum has been seeking answersand, as a result, has been able toidentify positive, practical stepswhich can be taken to improve thesitu<strong>at</strong>ion.First, the impact of criminal justice policy on reintegr<strong>at</strong>ing offendersshould not be underestim<strong>at</strong>ed. One of the results of the previous HomeSecretary’s, Michael Howard’s, ‘prison works’ policy was toovercrowd prisons. The first elements of prison regimes to suffer whenthey are overcrowded include work, educ<strong>at</strong>ion and training - the veryactivities which can help prisoners reintegr<strong>at</strong>e. So a beneficial criminal justicepolicy framework forms part of the solution the Forum is seeking.There are numerous examples of projects in Europe in which employers aredirectly involved in prison work, or in which prisoners are employed outsideprison in order to prepare for work on release. One initi<strong>at</strong>ive involved anoffshore oil company which trained Dutch prisoners to man oil rigs on release(EOEG, 1994). Another involved Network Southeast in London recruiting 90prisoners over two years (EOEG, 1996). There are also many examples ofemployers working with people serving community sentences. The key pointis th<strong>at</strong> the training of offenders must be relevant to the needs of today’s labourmarket and must be seen to be so by the offenders themselves, otherwise theirvalue is limited.Research undertaken by the Ministry of Justice in Northrhine Westphalia in1993, for example, showed th<strong>at</strong> 80% of prisoners who completed their trainingbut failed to find work on release re-offended, compared with 32% of thosewho found work. The 80% r<strong>at</strong>e was worse than the re-offending r<strong>at</strong>e amongprisoners who failed to complete their training (75%) (EOEG, 1994).Successful training within prison does not necessarily reduce the risk of reoffendingafterwards - especially if there are no opportunities to apply wh<strong>at</strong>they have learnt in the world of work afterwards.There is also a need to ensure th<strong>at</strong> offenders have basic skills training. At arecent Forum seminar, employers discussed the obstacles to employing moreex-offenders. Although they felt th<strong>at</strong> having a criminal record in itself was aproblem, their primary concern was the lack of basic skills among exoffenders.Their main concern was to recruit young people, whether exoffendersor not, who possessed <strong>at</strong>tributes such as proper motiv<strong>at</strong>ion,reliability, trustworthiness, ability to read and write, and the ability to work aspart of a team.NACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 14

Safer Society FEATURE EmployingPhoto: Michael GrieveThe point was underlined by Hans van der Ven, the Director ofHurkmans, a Dutch company specialising in laying pipes andunderground wiring. For him, offending was not the obstacle.His requirement was for motiv<strong>at</strong>ed young people, prepared towork hard and who were not distracted by an alcohol or drugproblem. He already employed a considerable number of exoffendersin his company. Thus, largescale and specificvoc<strong>at</strong>ional training projects may not always be appropri<strong>at</strong>e,particularly if relevant jobs are not available. This is not to ruleout voc<strong>at</strong>ional training, but to underline the importance of basicskills complemented, according to labour market circumstances,by training in specific skills.Many offenders have multiple problems which cannot be solvedsolely through help with <strong>employment</strong>. Chief among these arealcohol or drug abuse, although others include housing, welfareand family problems. At the root of these problems is theundoubted increase in drug-rel<strong>at</strong>ed crime in recent years. Someof the most successful <strong>employment</strong> initi<strong>at</strong>ives are those whichtake full account of these problems. A special section of a prisonin Rome, for example, provides intensive work to tackle drugabuse combined with work experience provided through a localco-oper<strong>at</strong>ive. Re-offending r<strong>at</strong>es are low and many prisonerswith previous drug problems are successfully placed withemployers.The aim of the WOBES <strong>employment</strong> programme in Austria is toprepared drug users for jobs in the ‘free’ labour market. Itprovides a ‘semi-protected’ environment in which intensivetraining is undertaken. Ex-offenders and other socially excludedgroups are recruited as temporary workers to undertakesubsidised <strong>employment</strong>, such as housing repairs and renov<strong>at</strong>ions.They are simultaneously offered accommod<strong>at</strong>ion, care and helpwith drug problems.The project is indic<strong>at</strong>ive of an increasing trend towards theprovision of more comprehensive packages of assistance tooffenders. Cumbria Prob<strong>at</strong>ion Service identifies the problemclearly:‘Many individuals under supervision by Cumbria Prob<strong>at</strong>ionService have multi-faceted, mutually-reinforcing problemsinvolving drug and alcohol misuse, un<strong>employment</strong> andaccommod<strong>at</strong>ion difficulties. These problems are intertwined withtheir offending behaviour in complex and varied ways ... and itis necessary to address each issue adequ<strong>at</strong>ely on its own termsand also in its links with the other issues.’Cumbria Prob<strong>at</strong>ion Service has established a project aimed <strong>at</strong>delivering ‘the kind of intensive, holistic approach to themultiple needs of offenders under supervision who have<strong>employment</strong>, accommod<strong>at</strong>ion and drug and alcohol problems’(Cumbria Prob<strong>at</strong>ion Service, 1997).Some foyer schemes also provide housing and training/<strong>employment</strong> skills for offenders. Partnership approaches havealso been developed in which close links between agencies havebeen established to provide a range of services for offenders. Butapart from these examples, genuine and effective multidimensionalprogrammes are still difficult to find.There is a need for continuity from sentence to release. Some ofthe least effective interventions we have seen have resulted fromleaving prisoners - or prob<strong>at</strong>ioners - isol<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>at</strong> the end of theirsentence. However effective the pre-release or prison trainingscheme, without action to bridge the gap between custody andcommunity, there will always be a tendency towards reoffending.The value of subsidising jobs for offenders also needs to beconsidered. In Italy, there are numerous examples of subsidiesbeing paid either to employers or to offenders, to assist them infinding <strong>employment</strong>. In Bologna, for example, there was a15 FEBRUARY 1999 SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE NACRO

Safer Society FEATURE Employing Offenders in EuropeCONFERENCEAnintern<strong>at</strong>ionalconference on‘Basic Skills forOffenders’,organised bythe Forum, isbeing held inParis on4-6 March1999. The feefor theconference is£250, includingaccommod<strong>at</strong>ion.For details,contact AndrewMcCall on 0181546 9978.ANDREW McCALLIS THE DIRECTOR OFTHE EUROPEANOFFENDEREMPLOYMENTFORUM, WHICHEXISTS TO TACKLERISING EUROPEANCRIME BY IMPROVINGPOLICY ANDPRACTICE IN THEREHABILITATION OFOFFENDERS.scheme which involved young offenders workingin a company for six to nine months, for whichthey received one million lira (approxim<strong>at</strong>ely£350) per month. If the company took on a drugaddict, they were given a direct grant and furtherfinancial incentives if permanent <strong>employment</strong>was provided (IARD, 1995).There is no consensus on the intrinsic value ofsubsidised <strong>employment</strong> for offenders. The ideaof ‘positive action’ in favour of offenders isan<strong>at</strong>hema in some countries, while for others it isa useful idea. The deb<strong>at</strong>e will continue but,wh<strong>at</strong>ever the political arguments, it is clear th<strong>at</strong>financial incentives can play a part inencouraging the <strong>employment</strong> of ex-offendersand, depending upon the overall <strong>employment</strong>situ<strong>at</strong>ion, their use may become widespread.Once we begin to piece together the elementswhich contribute to a successful interventionwith offenders, the question ‘Wh<strong>at</strong> can be done?’is not difficult to answer. The tricky question is‘How can we do it?’ and it is here th<strong>at</strong> we reachthe crux of the problem. Taking into account allof the excellent and effective initi<strong>at</strong>ivesidentified by the Forum, and allowing for somewe have missed, I would be surprised if theycover any more than 10% of the half a million orso people leaving prison in Europe each year. Itis perfectly clear th<strong>at</strong> most offenders do notbenefit from special integr<strong>at</strong>ed, holistic or labourmarket friendly <strong>employment</strong> initi<strong>at</strong>ives - thegood practice evident in specific projects doesnot transl<strong>at</strong>e into widespread, concerted action tobenefit larger numbers of offenders. Why? Ibelieve th<strong>at</strong> there are two reasons.First, <strong>employment</strong> and training provision foroffenders is not sufficiently controlled and coordin<strong>at</strong>edwithin the member st<strong>at</strong>es. Typically,not only will the prison service be providingwork, training and educ<strong>at</strong>ion for inm<strong>at</strong>es, so toomight the labour ministry, and a separ<strong>at</strong>e agencymay be providing a training or <strong>employment</strong>service. In addition, many prob<strong>at</strong>ion services willprovide <strong>employment</strong> services for people releasedfrom prison. Some prob<strong>at</strong>ion services may workwith prisoners prior to release. Once out ofprison, ex-offenders may be eligible for a rangeof training or <strong>employment</strong> services, provided bya plethora of agencies. This is without takingaccount of programmes on drug or substanceabuse, housing and welfare benefit issues - thelist goes on.There is a need for these agencies to talk to eachother as a m<strong>at</strong>ter of routine, to ensure th<strong>at</strong>inform<strong>at</strong>ion on effective practice is shared andth<strong>at</strong> programmes are monitored, so th<strong>at</strong> standardscan be continuously improved. At policy level,government departments should be in regularcommunic<strong>at</strong>ion with each other. It should ben<strong>at</strong>ural for ministries responsible for welfarem<strong>at</strong>ters to discuss the implic<strong>at</strong>ions of failings inthe justice system which lead to large andincreasing numbers of welfare dependants.Similarly, labour ministries should concernthemselves with the capacity of the justicesystem to produce people capable of securing<strong>employment</strong>. They should also n<strong>at</strong>urally considerwhether their training and <strong>employment</strong>programmes are accessible to prisoners and exoffenders.Second, the funders of programmes need toensure th<strong>at</strong> the services delivered are effective,th<strong>at</strong> they are producing results and th<strong>at</strong> theyprovide value for money. Governments mustmake it their business to ensure th<strong>at</strong> theprogrammes they support are meeting the rangeof offenders’ needs, are linking properly with thelabour market and are providing continuity fromsentence to release. In short, they need toestablish an active quality control andmonitoring system. With such a system, it wouldbe possible to avoid some of the mistakescurrently being made.I have sought to demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> the factorsleading to a successful intervention withoffenders are generally well known. The Forumhas helped develop a d<strong>at</strong>abase of inform<strong>at</strong>ionabout good practice, based on compar<strong>at</strong>ive study,research and deb<strong>at</strong>e. If the politicians can beencouraged to give un<strong>employment</strong>, crime andoffender rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion the priority they deserveand if governments can effectively control,monitor and co-ordin<strong>at</strong>e <strong>employment</strong> andtraining services for offenders, the mechanismsfor achieving positive results will be in place. ReferencesCumbria Prob<strong>at</strong>ion Service (1997), ‘Hard-up,Homeless and Hooked on the Hard Stuff’EOEG (1996), ‘Europe towards 2000: ConferenceReport’, European Offender Employment GroupEOEG (1994), ‘Wh<strong>at</strong> Works: Models of Good Practicein Europe’, European Offender Employment GroupIARD (1995), ‘Training Needs and Integr<strong>at</strong>ion into theWork Environment of Young People Leaving PenalInstitutions: Final Report’NACRO SAFER SOCIETY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1999 16