Avoiding fluoride in drinking water, Andhra Pradesh, India

Avoiding fluoride in drinking water, Andhra Pradesh, India

Avoiding fluoride in drinking water, Andhra Pradesh, India

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

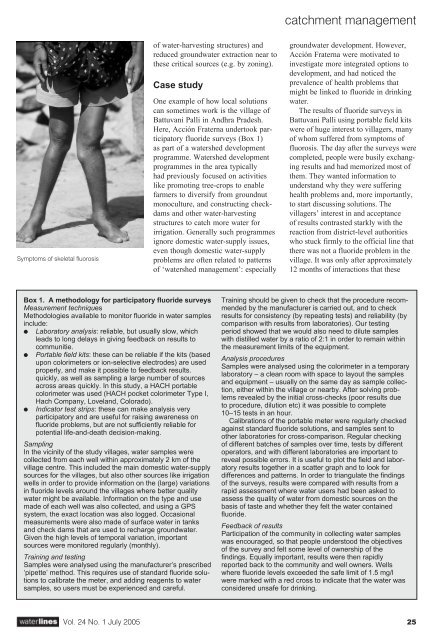

catchment management1Symptoms of skeletal fluorosisof <strong>water</strong>-harvest<strong>in</strong>g structures) andreduced ground<strong>water</strong> extraction near tothese critical sources (e.g. by zon<strong>in</strong>g).Case studyOne example of how local solutionscan sometimes work is the village ofBattuvani Palli <strong>in</strong> <strong>Andhra</strong> <strong>Pradesh</strong>.Here, Acción Fraterna undertook participatory<strong>fluoride</strong> surveys (Box 1)as part of a <strong>water</strong>shed developmentprogramme. Watershed developmentprogrammes <strong>in</strong> the area typicallyhad previously focused on activitieslike promot<strong>in</strong>g tree-crops to enablefarmers to diversify from groundnutmonoculture, and construct<strong>in</strong>g checkdamsand other <strong>water</strong>-harvest<strong>in</strong>gstructures to catch more <strong>water</strong> forirrigation. Generally such programmesignore domestic <strong>water</strong>-supply issues,even though domestic <strong>water</strong>-supplyproblems are often related to patternsof ‘<strong>water</strong>shed management’: especiallyground<strong>water</strong> development. However,Acción Fraterna were motivated to<strong>in</strong>vestigate more <strong>in</strong>tegrated options todevelopment, and had noticed theprevalence of health problems thatmight be l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>fluoride</strong> <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<strong>water</strong>.The results of <strong>fluoride</strong> surveys <strong>in</strong>Battuvani Palli us<strong>in</strong>g portable field kitswere of huge <strong>in</strong>terest to villagers, manyof whom suffered from symptoms offluorosis. The day after the surveys werecompleted, people were busily exchang<strong>in</strong>gresults and had memorized most ofthem. They wanted <strong>in</strong>formation tounderstand why they were suffer<strong>in</strong>ghealth problems and, more importantly,to start discuss<strong>in</strong>g solutions. Thevillagers’ <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> and acceptanceof results contrasted starkly with thereaction from district-level authoritieswho stuck firmly to the official l<strong>in</strong>e thatthere was not a <strong>fluoride</strong> problem <strong>in</strong> thevillage. It was only after approximately12 months of <strong>in</strong>teractions that these11Box 1. A methodology for participatory <strong>fluoride</strong> surveysMeasurement techniquesMethodologies available to monitor <strong>fluoride</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>water</strong> samples<strong>in</strong>clude:● Laboratory analysis: reliable, but usually slow, whichleads to long delays <strong>in</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g feedback on results tocommunitie.● Portable field kits: these can be reliable if the kits (basedupon colorimeters or ion-selective electrodes) are usedproperly, and make it possible to feedback results.quickly, as well as sampl<strong>in</strong>g a large number of sourcesacross areas quickly. In this study, a HACH portablecolorimeter was used (HACH pocket colorimeter Type I,Hach Company, Loveland, Colorado).● Indicator test strips: these can make analysis veryparticipatory and are useful for rais<strong>in</strong>g awareness on<strong>fluoride</strong> problems, but are not sufficiently reliable forpotential life-and-death decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g.Sampl<strong>in</strong>gIn the vic<strong>in</strong>ity of the study villages, <strong>water</strong> samples werecollected from each well with<strong>in</strong> approximately 2 km of thevillage centre. This <strong>in</strong>cluded the ma<strong>in</strong> domestic <strong>water</strong>-supplysources for the villages, but also other sources like irrigationwells <strong>in</strong> order to provide <strong>in</strong>formation on the (large) variations<strong>in</strong> <strong>fluoride</strong> levels around the villages where better quality<strong>water</strong> might be available. Information on the type and usemade of each well was also collected, and us<strong>in</strong>g a GPSsystem, the exact location was also logged. Occasionalmeasurements were also made of surface <strong>water</strong> <strong>in</strong> tanksand check dams that are used to recharge ground<strong>water</strong>.Given the high levels of temporal variation, importantsources were monitored regularly (monthly).Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and test<strong>in</strong>gSamples were analysed us<strong>in</strong>g the manufacturer’s prescribed‘pipette’ method. This requires use of standard <strong>fluoride</strong> solutionsto calibrate the meter, and add<strong>in</strong>g reagents to <strong>water</strong>samples, so users must be experienced and careful.Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g should be given to check that the procedure recommendedby the manufacturer is carried out, and to checkresults for consistency (by repeat<strong>in</strong>g tests) and reliability (bycomparison with results from laboratories). Our test<strong>in</strong>gperiod showed that we would also need to dilute sampleswith distilled <strong>water</strong> by a ratio of 2:1 <strong>in</strong> order to rema<strong>in</strong> with<strong>in</strong>the measurement limits of the equipment.Analysis proceduresSamples were analysed us<strong>in</strong>g the colorimeter <strong>in</strong> a temporarylaboratory – a clean room with space to layout the samplesand equipment – usually on the same day as sample collection,either with<strong>in</strong> the village or nearby. After solv<strong>in</strong>g problemsrevealed by the <strong>in</strong>itial cross-checks (poor results dueto procedure, dilution etc) it was possible to complete10–15 tests <strong>in</strong> an hour.Calibrations of the portable meter were regularly checkedaga<strong>in</strong>st standard <strong>fluoride</strong> solutions, and samples sent toother laboratories for cross-comparison. Regular check<strong>in</strong>gof different batches of samples over time, tests by differentoperators, and with different laboratories are important toreveal possible errors. It is useful to plot the field and laboratoryresults together <strong>in</strong> a scatter graph and to look fordifferences and patterns. In order to triangulate the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsof the surveys, results were compared with results from arapid assessment where <strong>water</strong> users had been asked toassess the quality of <strong>water</strong> from domestic sources on thebasis of taste and whether they felt the <strong>water</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>fluoride</strong>.Feedback of resultsParticipation of the community <strong>in</strong> collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>water</strong> sampleswas encouraged, so that people understood the objectivesof the survey and felt some level of ownership of thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. Equally important, results were then rapidlyreported back to the community and well owners. Wellswhere <strong>fluoride</strong> levels exceeded the safe limit of 1.5 mg/lwere marked with a red cross to <strong>in</strong>dicate that the <strong>water</strong> wasconsidered unsafe for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g.Vol. 24 No. 1 July 2005 25