Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hypothyroidism in Adults ...

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hypothyroidism in Adults ...

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hypothyroidism in Adults ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THYROIDVolume 22, Number 12, 2012ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.DOI: 10.1089/thy.2012.0205ORIGINAL STUDIES, REVIEWS,AND SCHOLARLY DIALOGTHYROID FUNCTION AND DYSFUNCTION<strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Adults</strong>:Cosponsored by the American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong>Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists and the American Thyroid AssociationJeffrey R. Garber, 1,2, * Rhoda H. Cob<strong>in</strong>, 3 Hosse<strong>in</strong> Gharib, 4 James V. Hennessey, 2 Irw<strong>in</strong> Kle<strong>in</strong>, 5Jeffrey I. Mechanick, 6 Rachel Pessah-Pollack, 6,7 Peter A. S<strong>in</strong>ger, 8 and Kenneth A. Woeber 9<strong>for</strong> the American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists and American Thyroid AssociationTask<strong>for</strong>ce on <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Adults</strong>Background: <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> has multiple etiologies and manifestations. Appropriate treatment requires anaccurate diagnosis and is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by coexist<strong>in</strong>g medical conditions. This paper describes evidence-basedcl<strong>in</strong>ical guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical management of hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> ambulatory patients.Methods: The development of these guidel<strong>in</strong>es was commissioned by the American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists(AACE) <strong>in</strong> association with American Thyroid Association (ATA). AACE and the ATA assembled atask <strong>for</strong>ce of expert cl<strong>in</strong>icians who authored this article. The authors exam<strong>in</strong>ed relevant literature and took anevidence-based medic<strong>in</strong>e approach that <strong>in</strong>corporated their knowledge and experience to develop a series ofspecific recommendations and the rationale <strong>for</strong> these recommendations. The strength of the recommendations andthe quality of evidence support<strong>in</strong>g each was rated accord<strong>in</strong>g to the approach outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the American Associationof <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists Protocol <strong>for</strong> Standardized Production of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong>—2010 update.Results: Topics addressed <strong>in</strong>clude the etiology, epidemiology, cl<strong>in</strong>ical and laboratory evaluation, management,and consequences of hypothyroidism. Screen<strong>in</strong>g, treatment of subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism, pregnancy, and areas<strong>for</strong> future research are also covered.Conclusions: Fifty-two evidence-based recommendations and subrecommendations were developed to aid <strong>in</strong>the care of patients with hypothyroidism and to share what the authors believe is current, rational, and optimalmedical practice <strong>for</strong> the diagnosis and care of hypothyroidism. A serum thyrotrop<strong>in</strong> is the s<strong>in</strong>gle best screen<strong>in</strong>gtest <strong>for</strong> primary thyroid dysfunction <strong>for</strong> the vast majority of outpatient cl<strong>in</strong>ical situations. The standard treatmentis replacement with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e. The decision to treat subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism when the serum thyrotrop<strong>in</strong>is less than 10 mIU/L should be tailored to the <strong>in</strong>dividual patient.By mutual agreement among the authors and the editors of their respective journals, this work is be<strong>in</strong>g published jo<strong>in</strong>tly <strong>in</strong> Thyroid andEndocr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>Practice</strong>.*Jeffrey R. Garber, M.D., is Chair of the American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists and American Thyroid Association Task<strong>for</strong>ce on<strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Adults</strong>. All authors after the first author are listed <strong>in</strong> alphabetical order.1 Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Division, Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, Boston, Massachusetts.2 Division of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts.3 New Jersey Endocr<strong>in</strong>e and Diabetes Associates, Ridgewood, New Jersey.4 Division of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology, Mayo Cl<strong>in</strong>ic, Rochester, M<strong>in</strong>nesota.5 The Thyroid Unit, North Shore University Hospital, Manhassett, New York.6 Division of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology, Mount S<strong>in</strong>ai Hospital, New York, New York.7 Division of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology, ProHealth Care Associates, Lake Success, New York.8 Keck School of Medic<strong>in</strong>e, University of Southern Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, Los Angeles, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.9 UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion, San Francisco, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.1200

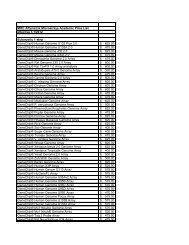

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR HYPOTHYROIDISM IN ADULTS 1201INTRODUCTIONThese updated cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice guidel<strong>in</strong>es (CPGs)(1–3) summarize the recommendations of the authors,act<strong>in</strong>g as a jo<strong>in</strong>t American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists(AACE) and American Thyroid Association(ATA) task <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> the diagnostic evaluation and treatmentstrategies <strong>for</strong> adults with hypothyroidism, as mandated by theBoard of Directors of AACE and the ATA.The ATA develops CPGs to provide guidance and recommendations<strong>for</strong> particular practice areas concern<strong>in</strong>g thyroiddisease, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g thyroid cancer. The guidel<strong>in</strong>es are not <strong>in</strong>clusiveof all proper approaches or methods, or exclusive ofothers. the guidel<strong>in</strong>es do not establish a standard of care, andspecific outcomes are not guaranteed. Treatment decisionsmust be made based on the <strong>in</strong>dependent judgment of healthcare providers and each patient’s <strong>in</strong>dividual circumstances. Aguidel<strong>in</strong>e is not <strong>in</strong>tended to take the place of physician judgment<strong>in</strong> diagnos<strong>in</strong>g and treatment of particular patients (<strong>for</strong>detailed <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation regard<strong>in</strong>g ATA guidel<strong>in</strong>es, see the SupplementaryData, available onl<strong>in</strong>e at www.liebertpub.com/thy).The AACE Medical <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> aresystematically developed statements to assist health careprofessionals <strong>in</strong> medical decision mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> specific cl<strong>in</strong>icalconditions. Most of their content is based on literature reviews.In areas of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, professional judgment is applied(<strong>for</strong> detailed <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation regard<strong>in</strong>g AACE guidel<strong>in</strong>es,see the Supplementary Data).These guidel<strong>in</strong>es are a document that reflects the currentstate of the field and are <strong>in</strong>tended to provide a work<strong>in</strong>g document<strong>for</strong> guidel<strong>in</strong>e updates s<strong>in</strong>ce rapid changes <strong>in</strong> this fieldare expected <strong>in</strong> the future. We encourage medical professionalsto use this <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> conjunction with their bestcl<strong>in</strong>ical judgment. The presented recommendations may notbe appropriate <strong>in</strong> all situations. Any decision by practitionersto apply these guidel<strong>in</strong>es must be made <strong>in</strong> light of local resourcesand <strong>in</strong>dividual patient circumstances.The guidel<strong>in</strong>es presented here pr<strong>in</strong>cipally address themanagement of ambulatory patients with biochemicallyconfirmed primary hypothyroidism whose thyroid status hasbeen stable <strong>for</strong> at least several weeks. They do not deal withmyxedema coma. The <strong>in</strong>terested reader is directed to the othersources <strong>for</strong> this <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation (4). The organization of theguidel<strong>in</strong>es is presented <strong>in</strong> Table 1.Serum thyrotrop<strong>in</strong> (TSH) is the s<strong>in</strong>gle best screen<strong>in</strong>g test <strong>for</strong>primary thyroid dysfunction <strong>for</strong> the vast majority of outpatientcl<strong>in</strong>ical situations, but it is not sufficient <strong>for</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g hospitalizedpatients or when central hypothyroidism is either presentor suspected. The standard treatment is replacement withL-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e which must be tailored to the <strong>in</strong>dividual patient.The therapy and diagnosis of subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism,which often rema<strong>in</strong>s undetected, is discussed. L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e <strong>for</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism,thyroid hormone <strong>for</strong> conditions other thanhypothyroidism, and nutraceuticals are considered.METHODSThis CPG adheres to the 2010 AACE Protocol <strong>for</strong> StandardizedProduction of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> published<strong>in</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>Practice</strong> (5). This updated protocol describes amore transparent methodology of rat<strong>in</strong>g the cl<strong>in</strong>ical evidenceand synthesiz<strong>in</strong>g recommendation grades. The protocol alsostipulates a rigorous multilevel review process.The process was begun by develop<strong>in</strong>g an outl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>for</strong> review<strong>in</strong>gthe pr<strong>in</strong>cipal cl<strong>in</strong>ical aspects of hypothyroidism.Computerized and manual searches of the medical literatureand various databases, primarily <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Medl<strong>in</strong>e Ò , werebased on specific section titles, thereby avoid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clusion ofTable 1. Organization of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Adults</strong>Introduction 1201Methods 1201Objectives 1204<strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> CPGs 1204Levels of scientific substantiation and recommendation grades (transparency) 1204Summary of recommendation grades 1205Topics Relat<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> 1205Epidemiology 1205Primary and secondary etiologies of hypothyroidism 1206Disorders associated with hypothyroidism 1207Signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism 1207Measurement of T 4 and T 3 1207Pitfalls encountered when <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g serum TSH levels 1208Other diagnostic tests <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism 1209Screen<strong>in</strong>g and aggressive case f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism 1209When to treat hypothyroidism 1210L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidism 1210Therapeutic endpo<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the treatment of hypothyroidism 1213When to consult an endocr<strong>in</strong>ologist 1214Concurrent conditions of special significance <strong>in</strong> hypothyroid patients 1214<strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy 1214Diabetes mellitus 1215Infertility 1215Page(cont<strong>in</strong>ued)

1202 GARBER ET AL.Table 1. (Cont<strong>in</strong>ued)PageObesity 1215Patients with normal thyroid tests 1215Depression 1215Nonthyroidal illness 1215Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals <strong>in</strong> the treatment of hypothyroidism 1216Overlap of symptoms <strong>in</strong> euthyroid and hypothyroid patients 1216Excess iod<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>take and hypothyroidism 1216Desiccated thyroid 12163,5,3¢-Triiodothyroacetic acid 1217Thyroid-enhanc<strong>in</strong>g preparations 1217Thyromimetic preparations 1217Selenium 1217Questions and Guidel<strong>in</strong>e Recommendations 1217Q1 When should anti-thyroid antibodies be measured? 1217R1 TPOAb measurements and subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism 1217R2 TPOAb measurements and nodular thyroid disease 1217R3 TPOAb measurements and recurrent miscarriage 1217R4 TSHRAb measurements <strong>in</strong> women with Graves’ disease who have1217had thyroidectomy or RAI treatment be<strong>for</strong>e pregnancyQ2 What is the role of cl<strong>in</strong>ical scor<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>in</strong> the diagnosis of patients1218with hypothyroidism?R5 Do not use cl<strong>in</strong>ical scor<strong>in</strong>g systems to diagnose hypothyroidism 1218Q3 What is the role of diagnostic tests apart from serum thyroid hormone levels and TSH <strong>in</strong>1218the evaluation of patients with hypothyroidism?R6 Do not use <strong>in</strong>direct tests to diagnose hypothyroidism 1218Q4 What are the preferred thyroid hormone measurements <strong>in</strong> addition to TSH <strong>in</strong> the assessment of1218patients with hypothyroidism?R7 When to use free T 4 vs. total T 4 1218R8 Us<strong>in</strong>g free T 4 to monitor L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment 1218R9 Estimat<strong>in</strong>g serum free T 4 <strong>in</strong> pregnancy 1218R10 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g T 3 to diagnose hypothyroidism 1218R11 Measur<strong>in</strong>g TSH <strong>in</strong> hospitalized patients 1218R12 Serum T 4 vs. TSH <strong>for</strong> management of central hypothyroidism 1218Q5 When should TSH levels be measured <strong>in</strong> patients be<strong>in</strong>g treated <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism? 1218R13 When to measure TSH <strong>in</strong> patients tak<strong>in</strong>g L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism 1218Q6 What should be considered the upper limit of the normal range of TSH values? 1218R14.1 Reference ranges <strong>for</strong> TSH, age, and lab variability 1218R14.2 Reference ranges <strong>for</strong> TSH <strong>in</strong> pregnant women 1218Q7 Which patients with TSH levels above a given laboratory’s reference range should be considered <strong>for</strong> 1219treatment with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e?R15 Treat<strong>in</strong>g patients with TSH above 10 mIU/L 1219R16 Treat<strong>in</strong>g if TSH is elevated but below 10 mIU/L 1219Q8 In patients with hypothyroidism be<strong>in</strong>g treated with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e what should the target TSH1219ranges be?R17 Target TSH when treat<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism 1219Q9 In patients with hypothyroidism be<strong>in</strong>g treated with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e who are pregnant, what should the 1219target TSH ranges be?R18 Target TSH when treat<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroid pregnant women 1219Q10 Which patients with normal serum TSH levels should be considered <strong>for</strong> treatment with1219L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e?R19.1 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>in</strong> pregnant women with ‘‘normal’’ TSH 1219R19.2 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>in</strong> women of child-bear<strong>in</strong>g age or pregnant with ‘‘normal’’ TSH1219and have positive TPOAb or history of miscarriage or hypothyroidismR19.3 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>in</strong> pregnant women or those plann<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy with TPOAb1219and serum TSH is > 2.5 mIU/LR19.4 Monitor<strong>in</strong>g of pregnant women with TPOAb or a ‘‘normal’’ TSH but > 2.5 mIU/L1219who are not tak<strong>in</strong>g L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>eQ11 Who, among patients who are pregnant, or plann<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy, or with other characteristics,1220should be screened <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism?R20.1.1 Universal screen<strong>in</strong>g of women plann<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>in</strong>cluded assisted reproduction 1220R20.1.2 Aggressive case f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism <strong>for</strong> women plann<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy 1220R20.2 Age and screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism 1220(cont<strong>in</strong>ued)

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR HYPOTHYROIDISM IN ADULTS 1203Table 1. (Cont<strong>in</strong>ued)PageR21 Aggressive case f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism—whom to target 1220Q12 How should patients with hypothyroidism be treated and monitored? 1220R22.1 Form of thyroid hormone <strong>for</strong> treatment of hypothyroidism 1220R22.2 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e comb<strong>in</strong>ations to treat hypothyroidism 1220R22.3 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e comb<strong>in</strong>ations1220to treat pregnant women or those plann<strong>in</strong>g pregnancyR22.4 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g desiccated thyroid hormone to treat hypothyroidism 1220R22.5 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g TRIAC (tiratricol) to treat hypothyroidism 1220R22.6 Resum<strong>in</strong>g L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> patients without cardiac events 1220R22.7.1 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>for</strong> overt hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> young healthy adults 1220R22.7.2 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>for</strong> overt hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> patients older than 50 to 60 years 1220R22.8 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>for</strong> subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism compared to overt1220hypothyroidismR22.9 Order of L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment and glucocorticoids <strong>in</strong> patients with adrenal1221<strong>in</strong>sufficiency and hypothyroidismR23 L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism—time to take, method of tak<strong>in</strong>g,1221and storageR24 Free T 4 as the target measurement when treat<strong>in</strong>g central hypothyroidism 1221R25.1 Test<strong>in</strong>g and treat<strong>in</strong>g women with hypothyroidism as soon as they become pregnant 1221R25.2 Goal TSH <strong>in</strong> pregnant women with hypothyroidism 1221R25.3 Monitor<strong>in</strong>g pregnant women with hypothyroidism 1221R26 Monitor<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroid patients who start drugs affect<strong>in</strong>g T 4 bioavailability1221or metabolismR27 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st target<strong>in</strong>g specific TSH values <strong>in</strong> hypothyroid patients who are1221not pregnantQ13 When should endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the care of patients with hypothyroidism? 1221R28 Type of hypothyroid patient who should be seen <strong>in</strong> consultation with1221an endocr<strong>in</strong>ologistQ14 Which patients should not be treated with thyroid hormone? 1221R29 Need <strong>for</strong> biochemical confirmation of the diagnosis be<strong>for</strong>e chronic treatment1221of hypothyroidismR30 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g thyroid hormone to treat obesity 1221R31 Thyroid hormone treatment and depression 1222Q15 What is the role of iod<strong>in</strong>e supplementation, dietary supplements, and nutraceuticals1222<strong>in</strong> the treatment of hypothyroidism?R32.1 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g iod<strong>in</strong>e supplementation to treat hypothyroidism1222<strong>in</strong> iod<strong>in</strong>e-sufficient areasR32.2 Inappropriate method <strong>for</strong> iod<strong>in</strong>e supplementation <strong>in</strong> pregnant women 1222R33 Prohibition aga<strong>in</strong>st us<strong>in</strong>g selenium as treatment or preventive measure1222<strong>for</strong> hypothyroidismR34 Recommendation regard<strong>in</strong>g dietary supplements, nutraceuticals,1222and products marked as ‘‘thyroid support’’ <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidismAreas <strong>for</strong> Future Research 1222Cardiac benefit from treat<strong>in</strong>g subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism 1222Cognitive benefit from treat<strong>in</strong>g subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism 1223L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e/L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e comb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy 1223L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e monotherapy 1223Thyroid hormone analogues 1223Screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> pregnancy 1223Agents and conditions hav<strong>in</strong>g an impact on L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e therapy and <strong>in</strong>terpretation1223of thyroid testsAuthor Disclosure Statement 1224Acknowledgments 1224References <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g authors’ evidence level (EL) rank<strong>in</strong>gs 1224Supplementary DataOnl<strong>in</strong>e at www.liebertpub.com/thy1. Supplementary <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation regard<strong>in</strong>g ATA and AACE guidel<strong>in</strong>es2. Complete list of guidel<strong>in</strong>e recommendationsNote: When referr<strong>in</strong>g to therapy and therapeutic preparations <strong>in</strong> the recommendations and elsewhere, L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>eare generally used <strong>in</strong>stead of their respective hormonal equivalents, T 4 and T 3 .AACE, American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CPG, <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>e; RAI,radioactive iod<strong>in</strong>e; T 3 , triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e; T 4 , thyrox<strong>in</strong>e; TPOAb, anti–thyroid peroxidase antibodies; TRIAC, 3,5,3¢-triiodothyroacetic acid;TSH, thyrotrop<strong>in</strong>; TSHRAb, TSH receptor antibodies.

1204 GARBER ET AL.unnecessary detail and exclusion of important studies. Compilationof the bibliography was a cont<strong>in</strong>ual and dynamicprocess. Once the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal cl<strong>in</strong>ical aspects of hypothyroidismwere def<strong>in</strong>ed, questions were <strong>for</strong>mulated with the <strong>in</strong>tent tothen develop recommendations that addressed these questions.The grad<strong>in</strong>g of recommendations was based on consensusamong the authors.The f<strong>in</strong>al document was approved by the American Associationof <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists (AACE) and AmericanThyroid Association (ATA), and was officially endorsed bythe American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE),American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and NeckSurgery (AAO-HNS), American College of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology(ACE), Italian Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists(AME), American Society <strong>for</strong> Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery(ASMBS), The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Society of Australia (ESA), InternationalAssociation of Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Surgeons (IAES), Lat<strong>in</strong>American Thyroid Society (LATS), and Ukranian Associationof Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Surgeons (UAES).ObjectivesThe purpose of these guidel<strong>in</strong>es is to present an updatedevidence-based framework <strong>for</strong> the diagnosis, treatment, andfollow-up of patients with hypothyroidism.<strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> CPGsCurrent guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> CPGs <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical medic<strong>in</strong>e emphasizean evidence-based approach rather than simply expert op<strong>in</strong>ion(6). Even though a purely evidence-based approach is notapplicable to all actual cl<strong>in</strong>ical scenarios, we have <strong>in</strong>corporatedthis <strong>in</strong>to these CPGs to provide objectivity.Levels of scientific substantiation andrecommendation grades (transparency)All cl<strong>in</strong>ical data that are <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong> these CPGs havebeen evaluated <strong>in</strong> terms of levels of scientific substantiation.The detailed methodology <strong>for</strong> assign<strong>in</strong>g evidence levels(ELs) to the references used <strong>in</strong> these CPGs has been reportedby Mechanick et al. (7), from which Table 2 is taken. Theauthors’ EL rat<strong>in</strong>gs of the references are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> theReferences section. The four-step approach that the authorsused to grade recommendations is summarized <strong>in</strong> Tables 3,4, 5, and 6 of the 2010 Standardized Production of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong><strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> (5), from which Table 3 is taken. Byexplicitly provid<strong>in</strong>g numerical and semantic descriptorsof the cl<strong>in</strong>ical evidence as well as relevant subjectivefactors and study flaws, the updated protocol has greatertransparency than the 2008 AACE protocol described byMechanick et al. (7).In these guidel<strong>in</strong>es, the grad<strong>in</strong>g system used <strong>for</strong> the recommendationsdoes not reflect the <strong>in</strong>struction of the recommendation,but the strength of the recommendation. Forexample <strong>in</strong> some grad<strong>in</strong>g systems ‘‘should not’’ implies thatthere is substantial evidence to support a recommendation.However the grad<strong>in</strong>g method employed <strong>in</strong> this guidel<strong>in</strong>eTable 2. Levels of Scientific Substantiation <strong>in</strong> Evidence-Based Medic<strong>in</strong>eLevel Description Comments1 Prospective, randomized, controlledtrials—large2 Prospective controlled trials with orwithout randomization—limitedbody of outcome data3 Other experimental outcomedata and nonexperimental dataData are derived from a substantial number of trials with adequatestatistical power <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a substantial number of outcome datasubjects.Large meta-analyses us<strong>in</strong>g raw or pooled data or <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>gquality rat<strong>in</strong>gsWell-controlled trial at one or more centersConsistent pattern of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the population <strong>for</strong> which therecommendation is made (generalizable data).Compell<strong>in</strong>g nonexperimental, cl<strong>in</strong>ically obvious, evidence (e.g., thyroidhormone treatment <strong>for</strong> myxedema coma), ‘‘all-or-none’’ <strong>in</strong>dicationLimited number of trials, small population sites <strong>in</strong> trialsWell-conducted s<strong>in</strong>gle-arm prospective cohort studyLimited but well-conducted meta-analysesInconsistent f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs or results not representative <strong>for</strong> the targetpopulationWell-conducted case-controlled studyNonrandomized, controlled trialsUncontrolled or poorly controlled trialsAny randomized cl<strong>in</strong>ical trial with one or more major or threeor more m<strong>in</strong>or methodological flawsRetrospective or observational dataCase reports or case seriesConflict<strong>in</strong>g data with weight of evidence unable to supporta f<strong>in</strong>al recommendation4 Expert op<strong>in</strong>ion Inadequate data <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> level 1, 2, or 3; necessitatesan expert panel’s synthesis of the literature and a consensusExperience basedTheory drivenLevels 1, 2, and 3 represent a given level of scientific substantiation or proof. Level 4 or Grade D represents unproven claims. It is the ‘‘bestevidence’’ based on the <strong>in</strong>dividual rat<strong>in</strong>gs of cl<strong>in</strong>ical reports that contributes to a f<strong>in</strong>al grade recommendation.Source: Mechanick et al., 2008 (7).

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR HYPOTHYROIDISM IN ADULTS 1205BestevidencelevelTable 3. Grade-Recommendation Protocol2010 AACE Protocol <strong>for</strong> Production of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong>—Step III: Grad<strong>in</strong>g of recommendations;How different evidence levels can be mappedto the same recommendation gradeSubjectivefactorimpactTwothirdsRecommendationconsensus Mapp<strong>in</strong>g a grade1 None Yes Direct A2 Positive Yes Adjust up A2 None Yes Direct B1 Negative Yes Adjust down B3 Positive Yes Adjust up B3 None Yes Direct C2 Negative Yes Adjust down C4 Positive Yes Adjust up C4 None Yes Direct D3 Negative Yes Adjust down D1,2,3,4 N/A No Adjust down DAdopted by the AACE and the ATA <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> CPG.a Start<strong>in</strong>g with the left column, best evidence levels (BELs),subjective factors, and consensus map to recommendation grades<strong>in</strong> the right column. When subjective factors have little or no impact(‘‘none’’), then the BEL is directly mapped to recommendationgrades. When subjective factors have a strong impact, then recommendationgrades may be adjusted up (‘‘positive’’ impact) or down(‘‘negative’’ impact). If a two-thirds consensus cannot be reached,then the recommendation grade is D.Source: Mechanick et al., 2010 (5).N/A, not applicable (regardless of the presence or absence ofstrong subjective factors, the absence of a two-thirds consensusmandates a recommendation grade D).enables authors to use this language even when the best evidencelevel available is ‘‘expert op<strong>in</strong>ion.’’ Although differentgrad<strong>in</strong>g systems were employed, an ef<strong>for</strong>t was made to makethese recommendations consistent with related portions of‘‘Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis:Management <strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> of the American Thyroid Associationand American Association of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists’’(8,9), as well as the ‘‘<strong>Guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> of the American ThyroidAssociation <strong>for</strong> the Diagnosis and Management of ThyroidDisease Dur<strong>in</strong>g Pregnancy and Postpartum’’ (10).The shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs of this evidence-based methodology <strong>in</strong>these CPGs are that many recommendations are based onweak scientific data (Level 3) or consensus op<strong>in</strong>ion (Level 4),rather than strong scientific data (Levels 1 and 2). There arealso the problems of (i) subjectivity on the part of the authorswhen weigh<strong>in</strong>g positive and negative, or epidemiologicversus experimental, data <strong>in</strong> order to arrive at an evidencebasedrecommendation grade or consensus op<strong>in</strong>ion, (ii) subjectivityon the part of the authors when weigh<strong>in</strong>g subjectiveattributes, such as cost effectiveness and risk-to-benefit ratios,<strong>in</strong> order to arrive at an evidence-based recommendationgrade or consensus op<strong>in</strong>ion, (iii) potentially <strong>in</strong>complete reviewof the literature by the authors despite extensive diligence,and (iv) bias <strong>in</strong> the available publications, whichorig<strong>in</strong>ate predom<strong>in</strong>antly from experienced cl<strong>in</strong>icians andlarge academic medical centers and may, there<strong>for</strong>e, not reflectthe experience at large. The authors, through an a priorimethodology and multiple levels of review, have tried toaddress these shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs by discussions with three experts(see Acknowledgments).Summary of recommendation gradesThe recommendations are evidence-based (Grades A, B, andC) or based on expert op<strong>in</strong>ion because of a lack of conclusivecl<strong>in</strong>ical evidence (Grade D). The ‘‘best evidence’’ rat<strong>in</strong>g level(BEL), which corresponds to the best conclusive evidencefound, accompanies the recommendation grade. Details regard<strong>in</strong>gthe mapp<strong>in</strong>g of cl<strong>in</strong>ical evidence rat<strong>in</strong>gs to these recommendationgrades have already been provided [see Levels ofscientific substantiation and recommendation grades (transparency)].In this CPG, a substantial number of recommendations areupgraded or downgraded because the conclusions may notapply <strong>in</strong> other situations (non-generalizability). For example,what applies to an elderly population with established cardiacdisease may not apply to a younger population without cardiacrisk factors. Whenever expert op<strong>in</strong>ions resulted <strong>in</strong> upgrad<strong>in</strong>gor downgrad<strong>in</strong>g a recommendation, it is explicitly stated afterthe recommendation.TOPICS RELATING TO HYPOTHYROIDISMEpidemiology<strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> may be either subcl<strong>in</strong>ical or overt. Subcl<strong>in</strong>icalhypothyroidism is characterized by a serum TSHabove the upper reference limit <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with a normalfree thyrox<strong>in</strong>e (T 4 ). This designation is only applicable whenthyroid function has been stable <strong>for</strong> weeks or more, the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroidaxis is normal, and there is norecent or ongo<strong>in</strong>g severe illness. An elevated TSH, usuallyabove 10 mIU/L, <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with a subnormal free T 4characterizes overt hypothyroidism.The results of four studies are summarized <strong>in</strong> Table 4.The National Health and Nutrition Exam<strong>in</strong>ation Survey(NHANES III) studied an unselected U.S. population over age12 between 1988 and 1994, us<strong>in</strong>g the upper limit of normal <strong>for</strong>Table 4. Prevalence of <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong>Study Subcl<strong>in</strong>ical Overt TSH CommentNHANES III 4.3% 0.3% 4.5Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence 8.5% 0.4% 5.0 Not on thyroid hormoneFram<strong>in</strong>gham 10.0 Over age 60 years: 5.9% women; 2.3% men; 39% ofwhom had subnormal T 4British Whickham 10.0 9.3% women; 1.2% menSources: Hollowell et al., 2002 (11); Canaris et al., 2000 (12); Saw<strong>in</strong> et al., 1985 (13); Vanderpump et al., 1995 (14); Vanderpump andTunbridge, 2002 (15).NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Exam<strong>in</strong>ation Survey.

1206 GARBER ET AL.TSH as 4.5 mIU/mL (11). The prevalence of subcl<strong>in</strong>ical diseasewas 4.3% and of overt disease was 0.3%. The Coloradothyroid disease prevalence survey, <strong>in</strong> which self-selected <strong>in</strong>dividualsattend<strong>in</strong>g a health fair were tested and an uppernormal TSH value of 5.0 mIU/L was used, reported a prevalenceof 8.5% and 0.4% <strong>for</strong> subcl<strong>in</strong>ical and overt disease,respectively, <strong>in</strong> people not tak<strong>in</strong>g thyroid hormone (12). In theFram<strong>in</strong>gham study, 5.9% of women and 2.3% of men over theage of 60 years had TSH values over 10 mIU/L, 39% of whomhad subnormal T 4 levels (13). In the British Whickham survey9.3% of women and 1.2% of men had serum TSH values over10 mIU/L (14,15). The <strong>in</strong>cidence of hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> womenwas 3.5 per 1000 survivors per year and <strong>in</strong> men it was 0.6 per1000 survivors per year. The risk of develop<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism<strong>in</strong> women with positive antibodies and elevated TSHwas 4% per year versus 2%–3% per year <strong>in</strong> those with eitheralone (14,15). In men the relative risk rose even more <strong>in</strong> eachcategory, but the rates rema<strong>in</strong>ed well below those of women.Primary and secondary etiologiesof hypothyroidismEnvironmental iod<strong>in</strong>e deficiency is the most commoncause of hypothyroidism on a worldwide basis (16). In areasof iod<strong>in</strong>e sufficiency, such as the United States, the mostcommon cause of hypothyroidism is chronic autoimmunethyroiditis (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis). Autoimmune thyroiddiseases (AITDs) have been estimated to be 5–10 times morecommon <strong>in</strong> women than <strong>in</strong> men. The ratio varies from seriesto series and is dependent on the def<strong>in</strong>ition of disease,whether it is cl<strong>in</strong>ically evident or not. In the Whickhamsurvey (14), <strong>for</strong> example, 5% of women and 1% of men hadboth positive antibody tests and a serum TSH value > 6.This <strong>for</strong>m of AITD (i.e., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, chronicautoimmune thyroiditis) <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> frequency with age(11), and is more common <strong>in</strong> people with other autoimmunediseases and their families (17–25). Goiter may or may notbe present.AITDs are characterized pathologically by <strong>in</strong>filtration ofthe thyroid with sensitized T lymphocytes and serologicallyby circulat<strong>in</strong>g thyroid autoantibodies. Autoimmunity to thethyroid gland appears to be an <strong>in</strong>herited defect <strong>in</strong> immunesurveillance, lead<strong>in</strong>g to abnormal regulation of immune responsivenessor alteration of present<strong>in</strong>g antigen <strong>in</strong> the thyroid(26,27).One of the keys to diagnos<strong>in</strong>g AITDs is determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gthe presence of elevated anti-thyroid antibody titerswhich <strong>in</strong>clude anti-thyroglobul<strong>in</strong> antibodies (TgAb), anti–microsomal/thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAb), andTSH receptor antibodies (TSHRAb). Many patients withchronic autoimmune thyroiditis are biochemically euthyroid.However, approximately 75% have elevated anti-thyroidantibody titers. Once present, these antibodies generallypersist, with spontaneous disappearance occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>frequently.Among the disease-free population <strong>in</strong> the NHANESsurvey, tests <strong>for</strong> TgAb were positive <strong>in</strong> 10.4% and TPOAb <strong>in</strong>11.3%. These antibodies were more common <strong>in</strong> women thanmen and <strong>in</strong>creased with age. Only positive TPOAb tests weresignificantly associated with hypothyroidism (11). The presenceof elevated TPOAb titers <strong>in</strong> patients with subcl<strong>in</strong>icalhypothyroidism helps to predict progression to overt hypothyroidism—4.3%per year with TPOAb vs. 2.6% per yearwithout elevated TPOAb titers (14,28). The higher risk ofdevelop<strong>in</strong>g overt hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong> TPOAb-positive patientsis the reason that several professional societies and manycl<strong>in</strong>ical endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists endorse measurement of TPOAbs <strong>in</strong>those with subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism.In patients with a diffuse, firm goiter, TPOAb should bemeasured to identify autoimmune thyroiditis. S<strong>in</strong>ce nonimmunologicallymediated mult<strong>in</strong>odular goiter is rarely associatedwith destruction of function<strong>in</strong>g tissue andprogression to hypothyroidism (29), it is important to identifythose patients with the nodular variant of autoimmune thyroiditis<strong>in</strong> whom these risks are significant. In some cases,particularly <strong>in</strong> those with thyroid nodules, f<strong>in</strong>e-needle aspiration(FNA) biopsy helps confirm the diagnosis and to excludemalignancy. Also, <strong>in</strong> patients with documentedhypothyroidism, measurement of TPOAb identifies the cause.In the presence of other autoimmune disease such astype 1 diabetes (20,21) or Addison’s disease (17,18), chromosomaldisorders such as Down’s (30) or Turner’s syndrome(31), and therapy with drugs such as lithium (32–34), <strong>in</strong>terferonalpha (35,36), and amiodarone (37) or excess iod<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>gestion(e.g., kelp) (38–40), TPOAb measurement may provide prognostic<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on the risk of develop<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism.TSHRAb may act as a TSH agonist or antagonist (41).Thyroid stimulat<strong>in</strong>g immunoglobul<strong>in</strong> (TSI) and/or thyrotrop<strong>in</strong>b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>hibitory immunoglobul<strong>in</strong> (TBII) levels,employ<strong>in</strong>g sensitive assays, should be measured <strong>in</strong> euthyroidor L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e–treated hypothyroid pregnant womenwith a history of Graves’ disease because they are predictorsof fetal and neonatal thyrotoxicosis (42). S<strong>in</strong>ce the risk <strong>for</strong>thyrotoxicosis correlates with the magnitude of elevation ofTSI, and s<strong>in</strong>ce TSI levels tend to fall dur<strong>in</strong>g the second trimester,TSI measurements are most <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mative when done<strong>in</strong> the early third trimester. The argument <strong>for</strong> measurementearlier <strong>in</strong> pregnancy is also based, <strong>in</strong> part, on determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gwhether establish<strong>in</strong>g a surveillance program <strong>for</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>gfetal and subsequent neonatal thyroid dysfunction isnecessary (43).<strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> may occur as a result of radioiod<strong>in</strong>e orsurgical treatment <strong>for</strong> hyperthyroidism, thyroid cancer, orbenign nodular thyroid disease and after external beam radiation<strong>for</strong> non–thyroid-related head and neck malignancies,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g lymphoma. A relatively new pharmacologic causeof iatrogenic hypothyroidism is the tyros<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ase <strong>in</strong>hibitors,most notably sunit<strong>in</strong>ib (44,45), which may <strong>in</strong>duce hypothyroidismthrough reduction of glandular vascularity and <strong>in</strong>ductionof type 3 deiod<strong>in</strong>ase activity.Central hypothyroidism occurs when there is <strong>in</strong>sufficientproduction of bioactive TSH (46,47) due to pituitary or hypothalamictumors (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g craniopharyngiomas), <strong>in</strong>flammatory(lymphocytic or granulomatous hypophysitis) or<strong>in</strong>filtrative diseases, hemorrhagic necrosis (Sheehan’s syndrome),or surgical and radiation treatment <strong>for</strong> pituitary orhypothalamic disease. In central hypothyroidism, serum TSHmay be mildly elevated, but assessment of serum free T 4 isusually low, differentiat<strong>in</strong>g it from subcl<strong>in</strong>ical primary hypothyroidism.Consumptive hypothyroidism is a rare condition that mayoccur <strong>in</strong> patients with hemangiomata and other tumors <strong>in</strong>which type 3 iodothyron<strong>in</strong>e deiod<strong>in</strong>ase is expressed, result<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> accelerated degradation of T 4 and triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e (T 3 )(48,49).

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR HYPOTHYROIDISM IN ADULTS 1207Disorders associated with hypothyroidismThe most common <strong>for</strong>m of thyroid failure has an autoimmuneetiology. Not surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, there is also an <strong>in</strong>creasedfrequency of other autoimmune disorders <strong>in</strong> this populationsuch as type 1 diabetes, pernicious anemia, primary adrenalfailure (Addison’s disease), myasthenia gravis, celiac disease,rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis (17–25),and rarely thyroid lymphoma (50).Dist<strong>in</strong>ct genetic syndromes with multiple autoimmuneendocr<strong>in</strong>opathies have been described, with some overlapp<strong>in</strong>gcl<strong>in</strong>ical features. The presence of two of the threemajor characteristics is required to diagnose the syndrome ofmultiple autoimmune endocr<strong>in</strong>opathies (MAEs). The def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gmajor characteristics <strong>for</strong> type 1 MAE and type 2 MAE areas follows: Type 1 MAE: Hypoparathyroidism, Addison’s disease,and mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by mutations <strong>in</strong>the autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE), result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>defective AIRE prote<strong>in</strong> (51). Autoimmune thyroiditis ispresent <strong>in</strong> about 10%–15% (52). Type 2 MAE: Addison’s disease, autoimmune thyroiditis,and type 1 diabetes known as Schmidt’s syndrome(53).When adrenal <strong>in</strong>sufficiency is present, the diagnosis ofsubcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism should be deferred until afterglucocorticoid therapy has been <strong>in</strong>stituted because TSHlevels may be elevated <strong>in</strong> the presence of untreated adrenal<strong>in</strong>sufficiency and may normalize with glucocorticoid therapy(54,55) (see L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidism).Signs and symptoms of hypothyroidismThe well-known signs and symptoms of hypothyroidismtend to be more subtle than those of hyperthyroidism. Dry sk<strong>in</strong>,cold sensitivity, fatigue, muscle cramps, voice changes, andconstipation are among the most common. Less commonlyappreciated and typically associated with severe hypothyroidismare carpal tunnel syndrome, sleep apnea, pituitaryhyperplasia that can occur with or without hyperprolact<strong>in</strong>emiaand galactorrhea, and hyponatremia that can occur with<strong>in</strong>several weeks of the onset of profound hypothyroidism. Although,<strong>for</strong> example, <strong>in</strong> the case of some symptoms such asvoice changes subjective (12,56) and objective (57) measuresdiffer. Several rat<strong>in</strong>g scales (56,58,59) have been used to assessthe presence and, <strong>in</strong> some cases, the severity of hypothyroidism,but have low sensitivity and specificity. While the exerciseof calculat<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ical scores has been largely superseded bysensitive thyroid function tests, it is useful to have objectivecl<strong>in</strong>ical measures to gauge the severity of hypothyroidism.Early as well as recent studies strongly correlate the degree ofhypothyroidism with ankle reflex relaxation time, a measurerarely used <strong>in</strong> current cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice today (60).Normalization of a variety of cl<strong>in</strong>ical and metabolic endpo<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g rest<strong>in</strong>g heart rate, serum cholesterol, anxietylevel, sleep pattern, and menstrual cycle abnormalities <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gmenometrorrhagia are further confirmatory f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsthat patients have been restored to a euthyroid state (61–65).Normalization of elevated serum creat<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ase or othermuscle (66) or hepatic enzymes follow<strong>in</strong>g treatment ofhypothyroidism (67) are additional, less well-appreciated andalso nonspecific therapeutic endpo<strong>in</strong>ts.Measurement of T 4 and T 3T 4 is bound to specific b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> serum. Theseare T 4 -b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g globul<strong>in</strong> (TBG) and, to a lesser extent,transthyret<strong>in</strong> or T 4 -b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prealbum<strong>in</strong> and album<strong>in</strong>. S<strong>in</strong>ceapproximately 99.97% of T 4 is prote<strong>in</strong>-bound, levels ofserum total T 4 will be affected by factors that alter b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dependent of thyroid disease (Table 5) (68,69). Accord<strong>in</strong>gly,methods <strong>for</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g estimat<strong>in</strong>g andmeasur<strong>in</strong>g) serum free T 4 , which is the metabolicallyavailable moiety (70), have been developed, and assessmentof serum free T 4 has now largely replaced measurement ofserum total T 4 as a measure of thyroid status. Thesemethods <strong>in</strong>clude the serum free T 4 <strong>in</strong>dex, which is derivedas the product of total T 4 and a thyroid hormone b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gratio, and the direct immunoassay of free T 4 after ultrafiltrationor equilibrium dialysis of serum or after addition ofanti-T 4 antibody to serum (71).A subnormal assessment of serum free T 4 serves to establisha diagnosis of hypothyroidism, whether primary, <strong>in</strong>which serum TSH is elevated, or central, <strong>in</strong> which serum TSHis normal or low (46,47). An assessment of serum free T 4(Table 6) is the primary test <strong>for</strong> detect<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong>antithyroid drug–treated or surgical or radioiod<strong>in</strong>e-ablatedpatients with previous hyperthyroidism <strong>in</strong> whom serum TSHmay rema<strong>in</strong> low <strong>for</strong> many weeks to months.In monitor<strong>in</strong>g patients with hypothyroidism on L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>ereplacement, blood <strong>for</strong> assessment of serum free T 4 should becollected be<strong>for</strong>e dos<strong>in</strong>g because the level will be transiently<strong>in</strong>creased by up to 20% after L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e adm<strong>in</strong>istration (72).In one small study of athyreotic patients, serum total T 4 levels<strong>in</strong>creased above basel<strong>in</strong>e by 1 hour and peaked at 2.5 hours,while serum free T 4 levels peaked at 3.5 hours and rema<strong>in</strong>edhigher than basel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>for</strong> 9 hours (72).In pregnancy, measurement of serum total T 4 is recommendedover direct immunoassay of serum free T 4 . Becauseof alterations <strong>in</strong> serum prote<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> pregnancy, directimmunoassay of free T 4 may yield lower values based onreference ranges established with normal nonpregnant sera.Moreover, many patients will have values below the nonpregnantreference range <strong>in</strong> the third trimester, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gTable 5. Factors That Alter Thyrox<strong>in</strong>eand Triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e B<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> SerumIncreased TBG Decreased TBG B<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>hibitorsInherited Inherited SalicylatesPregnancy Androgens FurosemideNeonatal state Anabolic steroids Free fatty acidsEstrogens Glucocorticoids Phenyto<strong>in</strong>Hepatitis Severe illness Carbamazep<strong>in</strong>ePorphyria Hepatic failure NSAIDs (variable,Hero<strong>in</strong>Nephrosistransient)Methadone Nicot<strong>in</strong>ic acid Hepar<strong>in</strong>Mitotane L-Asparag<strong>in</strong>ase5-FluorouracilSERMS (e.g.,tamoxifen,raloxifene)Perphanaz<strong>in</strong>eTBG, T 4 -b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g globul<strong>in</strong>; SERMS, selective estrogen receptormodulators; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-<strong>in</strong>flammatory drugs.

1208 GARBER ET AL.Table 6. Assessment of Free Thyrox<strong>in</strong>eTest Method CommentsFree T 4 <strong>in</strong>dex or freeT 4 estimateDirect immunoassayof free T 4Product of total T 4 and thyroid hormoneb<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g ratio or T 3 -res<strong>in</strong> uptakeWith physical separation us<strong>in</strong>g equilibriumdialysis or ultrafiltrationDirect immunoassayof free T 4Without physical separation us<strong>in</strong>g anti-T 4antibodyNormal values <strong>in</strong> pregnancy and with alterations<strong>in</strong> TBG b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g;Reduced values <strong>in</strong> pregnancy compared tononpregnant reference ranges; normal values withalterations <strong>in</strong> TBG b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gReduced values <strong>in</strong> pregnancy compared tononpregnant reference ranges; normal values withalterations <strong>in</strong> TBG b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gvalues obta<strong>in</strong>ed with equilibrium dialysis (73). F<strong>in</strong>ally,method-specific and trimester-specific reference ranges <strong>for</strong>direct immunoassay of free T 4 have not been generally established.By contrast, total T 4 <strong>in</strong>creases dur<strong>in</strong>g the first trimesterand the reference range is *1.5-fold that of thenonpregnant range throughout pregnancy (73,74).As is the case with T 4 ,T 3 is also bound to serum prote<strong>in</strong>s,pr<strong>in</strong>cipally TBG, but to a lesser extent than T 4 , *99.7%.Methods <strong>for</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g free T 3 concentration by direct immunoassayhave been developed and are <strong>in</strong> current use (71).However, serum T 3 measurement, whether total or free, haslimited utility <strong>in</strong> hypothyroidism because levels are oftennormal due to hyperstimulation of the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g function<strong>in</strong>gthyroid tissue by elevated TSH and to up-regulation of type 2iodothyron<strong>in</strong>e deiod<strong>in</strong>ase (75). Moreover, levels of T 3 are low<strong>in</strong> the absence of thyroid disease <strong>in</strong> patients with severe illnessbecause of reduced peripheral conversion of T 4 to T 3 and <strong>in</strong>creased<strong>in</strong>activation of thyroid hormone (76,77).Pitfalls encountered when <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>gserum TSH levelsMeasurement of serum TSH is the primary screen<strong>in</strong>g test<strong>for</strong> thyroid dysfunction, <strong>for</strong> evaluation of thyroid hormonereplacement <strong>in</strong> patients with primary hypothyroidism, and<strong>for</strong> assessment of suppressive therapy <strong>in</strong> patients with follicularcell–derived thyroid cancer. TSH levels vary diurnally byup to approximately 50% of mean values (78), with more recentreports <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g up to 40% variation on specimensper<strong>for</strong>med serially dur<strong>in</strong>g the same time of day (79). Valuestend to be lowest <strong>in</strong> the late afternoon and highest around thehour of sleep. In light of this, variations of serum TSH valueswith<strong>in</strong> the normal range of up to 40%–50% do not necessarilyreflect a change <strong>in</strong> thyroid status.TSH secretion is exquisitely sensitive to both m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>creasesand decreases <strong>in</strong> serum free T 4 , and abnormal TSHlevels occur dur<strong>in</strong>g develop<strong>in</strong>g hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidismbe<strong>for</strong>e free T 4 abnormalities are detectable (80).Accord<strong>in</strong>g to NHANES III (11), a disease-free population,which excludes those who self-reported thyroid disease orgoiter or who were tak<strong>in</strong>g thyroid medications, the uppernormal of serum TSH levels is 4.5 mIU/L. A ‘‘reference population’’taken from the disease-free population composed ofthose who were not pregnant, did not have laboratory evidenceof hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, did not havedetectable TgAb or TPOAb, and were not tak<strong>in</strong>g estrogens,androgens, or lithium had an upper normal TSH value of4.12 mIU/L. This was further supported by the Han<strong>for</strong>dThyroid Disease Study, which analyzed a cohort withoutevidence of thyroid disease, were seronegative <strong>for</strong> thyroidautoantibodies, were not on thyroid medications, and hadnormal thyroid ultrasound exam<strong>in</strong>ations (which did not disclosenodularity or evidence of thyroiditis) (81). This uppernormal value, however, may not apply to iod<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>sufficientregions even after becom<strong>in</strong>g iod<strong>in</strong>e sufficient <strong>for</strong> 20 years(82,83).More recently (84) the NHANES III reference populationwas further analyzed and normal ranges based on age, U.S.Office of Management of Budget ‘‘Race and Ethnicity’’ categories,and sex were determ<strong>in</strong>ed. These <strong>in</strong>dicated the 97.5thpercentile TSH values as low as 3.24 <strong>for</strong> African Americansbetween the ages of 30 and 39 years and as high as 7.84 <strong>for</strong>Mexican Americans ‡ 80 years of age. For every 10-year age<strong>in</strong>crease after 30–39 years, the 97.5th percentile of serum TSH<strong>in</strong>creases by 0.3 mIU/L. Body weight, anti-thyroid antibodystatus, and ur<strong>in</strong>ary iod<strong>in</strong>e had no significant impact on theseranges.The National Academy of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Biochemists, however,<strong>in</strong>dicated that 95% of <strong>in</strong>dividuals without evidence of thyroiddisease have TSH concentrations below 2.5 mIU/L (85), and ithas been suggested that the upper limit of the TSH referencerange be lowered to 2.5 mIU/L (86). While many patients withTSH concentrations <strong>in</strong> this range do not develop hypothyroidism,those patients with AITD are much more likely todevelop hypothyroidism, either subcl<strong>in</strong>ical or overt (87) (seeTherapeutic endpo<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the treatment of hypothyroidism <strong>for</strong>further discussion).In <strong>in</strong>dividuals without serologic evidence of AITD, TSHvalues above 3.0 mIU/L occur with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g frequency withage, with elderly ( > 80 years of age) <strong>in</strong>dividuals hav<strong>in</strong>g a23.9% prevalence of TSH values between 2.5 and 4.5 mIU/L,and a 12% prevalence of TSH concentrations above 4.5 mIU/L(88). Thus, very mild TSH elevations <strong>in</strong> older <strong>in</strong>dividuals maynot reflect subcl<strong>in</strong>ical thyroid dysfunction, but rather be anormal manifestation of ag<strong>in</strong>g. The caveat is that while thenormal TSH reference range—particularly <strong>for</strong> some subpopulations—mayneed to be narrowed (85,86), the normal referencerange may widen with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g age (84). Thus, not allpatients who have mild TSH elevations are hypothyroid andthere<strong>for</strong>e would not require thyroid hormone therapy.There are other pitfalls <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the serumTSH because abnormal levels are observed <strong>in</strong> various nonthyroidalstates. Serum TSH may be suppressed <strong>in</strong> hospitalizedpatients with acute illness, and levels below 0.1 mIU/L <strong>in</strong>comb<strong>in</strong>ation with subnormal free T 4 estimates may be seen <strong>in</strong>critically ill patients, especially <strong>in</strong> those receiv<strong>in</strong>g dopam<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong>fusions (89) or pharmacologic doses of glucocorticoids (90).In addition, TSH levels may <strong>in</strong>crease to levels above normal,

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR HYPOTHYROIDISM IN ADULTS 1209but generally below 20 mIU/L dur<strong>in</strong>g the recovery phasefrom nonthyroidal illness (91). Thus, there are limitations toTSH measurements <strong>in</strong> hospitalized patients and, there<strong>for</strong>e,they should be only per<strong>for</strong>med if there is an <strong>in</strong>dex of suspicion<strong>for</strong> thyroid dysfunction (76).Serum TSH typically falls, but <strong>in</strong>frequently to below0.1 mU/L, dur<strong>in</strong>g the first trimester of pregnancy due to thethyroid stimulatory effects of human chorionic gonadotrop<strong>in</strong>and returns to normal <strong>in</strong> the second trimester (10) (seeTable 7).TSH secretion may be <strong>in</strong>hibited by adm<strong>in</strong>istration of subcutaneousoctreotide, which does not cause persistent centralhypothyroidism (92), and by oral bexarotene, which almostalways does (93). In addition, patients with anorexia nervosamay have low TSH levels <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with low levels offree T 4 (94), mimick<strong>in</strong>g what may be seen <strong>in</strong> critically ill patientsand <strong>in</strong> patients with central hypothyroidism due topituitary and hypothalamic disorders.Patients with nonfunction<strong>in</strong>g pituitary adenomas, withcentral hypothyroidism, may have mildly elevated serumTSH levels, generally not above 6 or 7 mIU/L, due to secretionof bio<strong>in</strong>active iso<strong>for</strong>ms of TSH (47). TSH levels mayalso be elevated <strong>in</strong> association with elevated serum thyroidhormone levels <strong>in</strong> patients with resistance to thyroid hormone(95). Heterophilic or <strong>in</strong>terfer<strong>in</strong>g antibodies, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>ghuman antianimal (most commonly mouse) antibodies,rheumatoid factor, and autoimmune anti-TSH antibodiesmay cause falsely elevated serum TSH values (96). Lastly,adrenal <strong>in</strong>sufficiency, as previously noted <strong>in</strong> Disorders associatedwith hypothyroidism, may be associated with TSH elevationsthat are reversed with glucocorticoid replacement(54,55).Other diagnostic tests <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidismPrior to the advent of rout<strong>in</strong>e validated chemical measurementsof serum thyroid hormones and TSH, tests thatcorrelated with thyroid status, but not sufficiently specific todiagnose hypothyroidism, were used to diagnose hypothyroidismand to gauge the response to thyroid hormone therapy.The follow<strong>in</strong>g are previous notable and more recentexamples: Basal metabolic rate was the ‘‘gold standard’’ <strong>for</strong> diagnosis.Extremely high and low values correlate well withmarked hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, respectively,but are affected by many unrelated, diverseconditions, such as fever, pregnancy, cancer, acromegaly,hypogonadism, and starvation (97,98). Decrease <strong>in</strong> sleep<strong>in</strong>g heart rate (61) Elevated total cholesterol (62,99) as well as low-densitylipoprote<strong>in</strong> (LDL) (99,100) and the highly atherogenicsubfraction Lp (a) (101) Delayed Achilles reflex time (60) Increased creat<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ase due to an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the MMfraction, which can be marked and lead to an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>the MB fraction. There is a less marked <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>myoglob<strong>in</strong> (66) and no change <strong>in</strong> tropon<strong>in</strong> levels even <strong>in</strong>the presence of an <strong>in</strong>creased MB fraction (102).Screen<strong>in</strong>g and aggressive case f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<strong>for</strong> hypothyroidismCriteria <strong>for</strong> population screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clude: A condition that is prevalent and an important healthproblem Early diagnosis is not usually made Diagnosis is simple and accurate Treatment is cost effective and safeDespite this seem<strong>in</strong>gly straight<strong>for</strong>ward guidance, expertpanels have disagreed about TSH screen<strong>in</strong>g of the generalpopulation (Table 8). The ATA recommends screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> alladults beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g at age 35 years and every 5 years thereafterTable 7. Thyrotrop<strong>in</strong> Upper NormalGroup, study, society TSH upper normal CommentsNACB 2.5 When there is no evidence of thyroid diseaseNHANES III, disease free 4.5 No self-reported thyroid diseaseNot on thyroid medicationsNHANES III, reference population 4.12 No self-reported thyroid diseaseNot on thyroid medicationsNegative anti-thyroid antibodiesNot pregnantNot on estrogens, androgens, lithiumHan<strong>for</strong>d Thyroid Disease Study 4.10 No evidence of thyroid diseaseNegative anti-thyroid antibodiesNot on thyroid medicationsNormal ultrasound (no nodules or thyroiditis)Pregnancy, first trimester 2.0–2.5 See sections L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidismand <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancyPregnancy, second trimester 3.0 See sections L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidismand <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancyPregnancy, third trimester 3.5 See sections L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidismand <strong>Hypothyroidism</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancySources: Stagnaro-Green et al., 2011 (10); Hollowell et al., 2002 (11); Hamilton et al., 2008 (81); Baloch et al., 2003 (85).NACB, National Academy of <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Biochemists; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Exam<strong>in</strong>ation Survey.

1210 GARBER ET AL.Table 8. Recommendations of Six OrganizationsRegard<strong>in</strong>g Screen<strong>in</strong>g of Asymptomatic <strong>Adults</strong><strong>for</strong> Thyroid DysfunctionOrganizationAmerican ThyroidAssociationAmerican Associationof <strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong>Endocr<strong>in</strong>ologistsAmerican Academyof Family PhysiciansAmerican College ofPhysiciansU.S. Preventive ServicesTask ForceRoyal Collegeof Physiciansof LondonScreen<strong>in</strong>g recommendationsWomen and men > 35 yearsof age should be screenedevery 5 years.Older patients,especially women,should be screened.Patients ‡ 60 years of ageshould be screened.Women ‡ 50 years of agewith an <strong>in</strong>cidental f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsuggestive of symptomaticthyroid disease should beevaluated.Insufficient evidence <strong>for</strong>or aga<strong>in</strong>st screen<strong>in</strong>gScreen<strong>in</strong>g of the healthyadult population unjustifiedSources: Bask<strong>in</strong> et al., 2002 (2); Ladenson et al., 2000 (103); AmericanAcademy of Family Physicians, 2002 (104); Helfand and Redfern,1998 (105); Vanderpump et al., 1996 (107); Helfand, 2004 (108).(103). AACE recommends rout<strong>in</strong>e TSH measurement <strong>in</strong> olderpatients—age not specified—especially women (2). TheAmerican Academy of Family Physicians recommends rout<strong>in</strong>escreen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> asymptomatic patients older than age 60years (104), and the American College of Physicians recommendscase f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> women older than 50 years (105). Incontrast, a consensus panel (106), the Royal College of Physiciansof London (107), and the U.S. Preventive Services TaskForce (108) do not recommend rout<strong>in</strong>e screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> thyroiddisease <strong>in</strong> adults. For recommendations <strong>in</strong> pregnancy, seeRecommendations 20.1.1 and 20.1.2.While there is no consensus about population screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong>hypothyroidism there is compell<strong>in</strong>g evidence to support casef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> hypothyroidism <strong>in</strong>: Those with autoimmune disease, such as type 1 diabetes(20,21) Those with pernicious anemia (109,110) Those with a first-degree relative with autoimmunethyroid disease (19) Those with a history of neck radiation to the thyroidgland <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g radioactive iod<strong>in</strong>e therapy <strong>for</strong> hyperthyroidismand external beam radiotherapy <strong>for</strong> headand neck malignancies (111–113) Those with a prior history of thyroid surgery or dysfunction Those with an abnormal thyroid exam<strong>in</strong>ation Those with psychiatric disorders (114) Patients tak<strong>in</strong>g amiodarone (37) or lithium (32–34) Patients with ICD-9 diagnoses as presented <strong>in</strong> Table 9When to treat hypothyroidismAlthough there is general agreement that patients withprimary hypothyroidism with TSH levels above 10 mIU/LTable 9. ICD-9-CM Codes to SupportThyrotrop<strong>in</strong> Test<strong>in</strong>gAdrenal <strong>in</strong>sufficiency 255.41Alopecia 704.00Anemia, unspecified deficiency 281.9Cardiac dysrhythmia, unspecified 427.9Changes <strong>in</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> texture 782.8Congestive heart failure 428.0Constipation 564.00Dementia294.8BADiabetes mellitus, type 1 250.01Dysmenorrhea 625.3Hypercholesterolemia 272.0Hypertension 401.9Mixed hyperlipidemia 272.2Malaise and fatigue 780.79Myopathy, unspecified 359.9Prolonged QT <strong>in</strong>terval 794.31Vitiligo 709.01Weight ga<strong>in</strong> 783.9MICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, N<strong>in</strong>th Revision,<strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical</strong> Modification (www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm).should be treated (106,115–117), which patients with TSHlevels of 4.5–10 mIU/L will benefit is less certa<strong>in</strong> (118,119). Asubstantial number of studies have been done on patientswith TSH levels between 2.5 and 4.5, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g beneficialresponse <strong>in</strong> atherosclerosis risk factors such as atherogeniclipids (120–123), impaired endothelial function (124,125), and<strong>in</strong>tima media thickness (126). This topic is further discussed <strong>in</strong>the section Cardiac benefit from treat<strong>in</strong>g subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidism.However, there are virtually no cl<strong>in</strong>ical outcome data tosupport treat<strong>in</strong>g patients with subcl<strong>in</strong>ical hypothyroidismwith TSH levels between 2.5 and 4.5 mIU/L. The possibleexception to this statement is pregnancy because the rate ofpregnancy loss, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g spontaneous miscarriage be<strong>for</strong>e 20weeks gestation and stillbirth after 20 weeks, have been reportedto be <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> anti-thyroid antibody–negativewomen with TSH values between 2.5 and 5.0 (127).L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e treatment of hypothyroidismS<strong>in</strong>ce the generation of biologically active T 3 by the peripheralconversion of T 4 to T 3 was documented <strong>in</strong> 1970 (128),L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e monotherapy has become the ma<strong>in</strong>stay of treat<strong>in</strong>ghypothyroidism, replac<strong>in</strong>g desiccated thyroid and other<strong>for</strong>ms of L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e comb<strong>in</strong>ationtherapy. Although a similar quality of life (129) and circulat<strong>in</strong>gT 3 levels (130) have been reported <strong>in</strong> patients treated withL-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e compared with <strong>in</strong>dividuals without thyroid disease,other studies have not shown levels of satisfactioncomparable to euthyroid controls (131). A number of studies,follow<strong>in</strong>g a 1999 report cit<strong>in</strong>g the benefit of L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e comb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy (132), have re-addressedthe benefits of synthetic L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>ecomb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy but have largely failed toconfirm an advantage of this approach to improve cognitiveor mood outcomes <strong>in</strong> hypothyroid <strong>in</strong>dividuals treated with L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e alone (133,134).Yet several matters rema<strong>in</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>. What should the ratiosof L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and L-triiodothyron<strong>in</strong>e replacement be (133)?What is the pharmacodynamic equivalence of L-thyrox<strong>in</strong>e and