Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

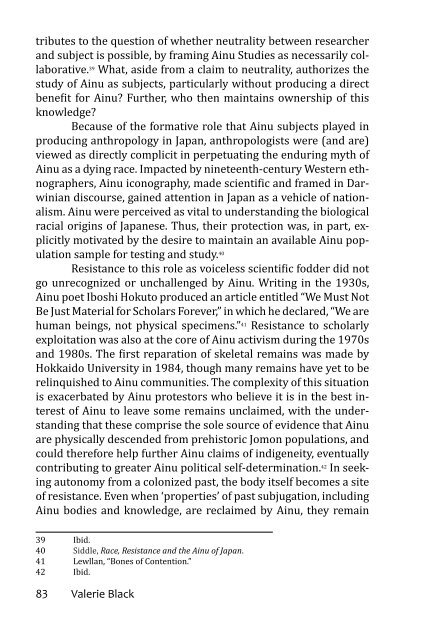

tributes to the question <strong>of</strong> whether neutrality between researcherand subject is possible, by framing Ainu <strong>Studies</strong> as necessarily collaborative.39 What, aside from a claim to neutrality, authorizes thestudy <strong>of</strong> Ainu as subjects, particularly without producing a directbenefit for Ainu? Further, who then maintains ownership <strong>of</strong> thisknowledge?Because <strong>of</strong> the formative role that Ainu subjects played inproducing anthropology in Japan, anthropologists were (and are)viewed as directly complicit in perpetuating the enduring myth <strong>of</strong>Ainu as a dying race. Impacted by nineteenth-century Western ethnographers,Ainu iconography, made scientific and framed in Darwiniandiscourse, gained attention in Japan as a vehicle <strong>of</strong> nationalism.Ainu were perceived as vital to understanding the biologicalracial origins <strong>of</strong> Japanese. Thus, their protection was, in part, explicitlymotivated by the desire to maintain an available Ainu populationsample for testing and study. 40Resistance to this role as voiceless scientific fodder did notgo unrecognized or unchallenged by Ainu. Writing in the 1930s,Ainu poet Iboshi Hokuto produced an article entitled “We Must NotBe Just Material for Scholars Forever,” in which he declared, “We arehuman beings, not physical specimens.” 41 Resistance to scholarlyexploitation was also at the core <strong>of</strong> Ainu activism during the 1970sand 1980s. The first reparation <strong>of</strong> skeletal remains was made byHokkaido University in 1984, though many remains have yet to berelinquished to Ainu communities. The complexity <strong>of</strong> this situationis exacerbated by Ainu protestors who believe it is in the best interest<strong>of</strong> Ainu to leave some remains unclaimed, with the understandingthat these comprise the sole source <strong>of</strong> evidence that Ainuare physically descended from prehistoric Jomon populations, andcould therefore help further Ainu claims <strong>of</strong> indigeneity, eventuallycontributing to greater Ainu political self-determination. 42 In seekingautonomy from a colonized past, the body itself becomes a site<strong>of</strong> resistance. Even when ‘properties’ <strong>of</strong> past subjugation, includingAinu bodies and knowledge, are reclaimed by Ainu, they remain39 Ibid.40 Siddle, Race, Resistance and the Ainu <strong>of</strong> Japan.41 Lewllan, “Bones <strong>of</strong> Contention.”42 Ibid.the currency by which power and self-determination are won.The metaphor <strong>of</strong> indigeneity suggests there is a trajectorythat Ainu <strong>Studies</strong>, as a form <strong>of</strong> Indigenous <strong>Studies</strong>, currently follows.Yet, the assumption <strong>of</strong> neutrality, and a necessary distinctionbetween academics and activism, is itself a legacy <strong>of</strong> colonialism.ConclusionDoes the recognition <strong>of</strong> Ainu rights by means <strong>of</strong> a global indigenousidentity address the legacies <strong>of</strong> colonization, or merelyperpetuate them? By asking this question, I do not suggest thatAinu political activism and organization is either futile or disempowered.The conspicuous absence <strong>of</strong> legal recognition accordedto other minority groups in Japan suggests that Ainu identity asindigenous supersedes Ainu identity as Japanese, as the source <strong>of</strong>power behind this identity is not produced within the Japanesestate. It is important to consider the possibility that the processthrough which these modes <strong>of</strong> engagement gain power may reproducethe underlying dynamics <strong>of</strong> colonization, including the mythology<strong>of</strong> a timeless and cohesive culture irreversibly diminishedby contact with colonizing powers, as opposed to creating a futurein which national and cultural identities are not discrete and hierarchical.This outcome is neither wholly good nor wholly bad;breaking away from the myth <strong>of</strong> colonization necessarily meansdiscarding a belief in the myth <strong>of</strong> progress.The metaphor <strong>of</strong> indigeneity is empowering to indigenousindividuals and groups where these individuals and groups areable to willingly invoke this identity to direct change. Yet, the existence<strong>of</strong> international laws <strong>of</strong> protection for indigenous populationssuggests that ‘protection’ is granted, or bestowed, by a powerunquestionably positioned to do so. Where rights and powers attainedarise directly or indirectly from the metaphor <strong>of</strong> indigeneity,it is important to consider the power <strong>of</strong> this metaphor in shapingand reshaping identities, including self-identities as indigenousand colonizing respectively, at the expense <strong>of</strong> other, potentiallymore integrated, identities.83 Valerie Black Ainu Indigeneity 84