MAX Teaching with Reading and Writing - Ects.org

MAX Teaching with Reading and Writing - Ects.org

MAX Teaching with Reading and Writing - Ects.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong>With <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Writing</strong>Mark A. F<strong>org</strong>et, Ph.D.Using Literacy SkillsTo Help Students Learn Subject Matter<strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> Workshop MaterialsMark A. F<strong>org</strong>et, Ph.D.Director of Staff Development<strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong>, Inc.6857 T.R. 215Findlay, OH 45840404-441-7008mf<strong>org</strong>et@maxteaching.comwww.maxteaching.com©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com1

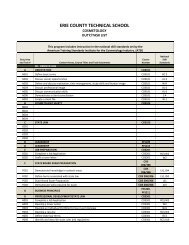

BeforeLearning3 DAILY ELEMENTS OF READING/WRITING TO LEARNAfterLearning1. _____2. _____3. _____1. <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> Framework (<strong>MAX</strong>)2. 4 Components of Successful Cooperative Learning (CL)3. Skill Acquisition Model (SAM)CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES USING READING/WRITING1. _____2. _____3. _____1. _____2. _____3. _____4. _____5. _____6. _____7. _____8. _____9. _____10. _____11. _____12. _____13. _____14. _____15. _____16. _____17. _____18. _____19. _____20. _____21. _____1. Anticipation Guides2. Cubing3. Directed <strong>Reading</strong>/Thinking Activity in Fiction4. Directed <strong>Reading</strong>/Thinking Activity in Non-Fiction5. Focused Free Write6. G.I.S.T.7. Graphic Representations8. Hunt for Main Ideas9. I.N.S.E.R.T.10. Interactive Cloze Procedure11. Math Translation12. No-Research Papers13. Paired <strong>Reading</strong> Activity14. PQR 2 ST+15. Pre-Learning Concept Checks16. PreP17. Previewing18. Question Mark (Questions for Quality Thinking Bookmark)19. ReQuest20. Three-Level Study Guides21. Two-Column Notes1. _____2. _____3. _____4. _____5. _____6. _____7. _____8. _____9. _____10. _____11. _____12. _____13. _____14. _____15. _____16. _____17. _____18. _____19. _____20. _____21. _____©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com2

ANTICIPATION GUIDE: How Students Learn Most EffectivelyBefore <strong>Reading</strong>: In the space to the left of each statement, place a check mark( ƒ ) if you agree or think the statement is true.During or After <strong>Reading</strong>: Add new check marks or cross through those aboutwhich you have changed your mind. Keep in mind that this is not like thetraditional “worksheet.” You may have to put on your thinking caps <strong>and</strong> “readbetween the lines.” Use the space under each statement to note the page, column,<strong>and</strong> paragraph(s) where you have found information to support your thinking.___1. Students must participate actively in their learning in order for the materiallearned to become personal knowledge.___2. The best place for low-performing readers to improve their reading skills isin a remedial reading class.___3. Most students from kindergarten through twelfth grade can practice criticalthinking about virtually any subject matter.___4. In most school-related learning situations, students <strong>and</strong> teachers retain muchmore from what they discuss than from what they read.___5. Teachers should rely heavily on the textbook as a tool to help students learntheir subject matter.___6. Through daily repetition of practice in using communication skills to learn<strong>and</strong> process new information, students can become autonomous learners.___7. <strong>Reading</strong> is thinking – <strong>and</strong> students’ scores on most state-m<strong>and</strong>atedst<strong>and</strong>ardized tests would improve if teachers were to provide students <strong>with</strong> guidedpractice in reading/thinking skills in their daily routine of course contentinstruction.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com3

This page is intentionally left blank.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com4

HOW STUDENTS LEARN MOST EFFECTIVELY 1Research suggests that we remember about 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear, 30%of what we see, <strong>and</strong> 70% of what we, ourselves, say. How much do we remember of all thebooks we read in college? Is 10% a good estimate? We read the books <strong>and</strong> most likely didcomprehend what we read <strong>and</strong> held on to the knowledge for a test, paper, or discussion. Most ofthat retention was momentary underst<strong>and</strong>ing but was not processed as personal knowledge forourselves. Comprehending what you read <strong>and</strong> long-term retention are definitely two separateentities.Research also tells us that “85% of the knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills presented to students in schoolcomes to them in some form of language: teachers talking, materials to read, films to watch <strong>and</strong>listen to, <strong>and</strong> so forth.” If students only retain 20% of what they hear, then is frequent lecture aneffective way to teach, <strong>and</strong> is it an effective use of learners’ time? If we remember 70% of whatwe say, is it any wonder that teachers who often lecture seem so knowledgeable?Percentages aside, teachers, especially, know how beneficial it is to talk to someone elseabout subject matter. As good learners, we know from experience that when we discussed <strong>with</strong>someone else, we clarified subject matter, made connections among points of the subject matterthat we might not have realized before, <strong>and</strong> mentally <strong>and</strong> verbally interacted <strong>with</strong> the ideas of ourpartner(s) in the discussion.These same concepts apply to our students. An interactive learning situation is superior to thepassive reception of information of the traditional classroom. When students work cooperativelyto construct the meaning from a piece of text, they learn more deeply, <strong>and</strong> they are helping oneanother learn how to learn. In order to motivate students to think about, learn, <strong>and</strong> discuss whatthey have read, we should use a framework of instruction that allows students to be active intheir own learning.Generally speaking, reading is not taught beyond the third grade in most school systems. If astudent has not mastered reading comprehension skills by the fourth grade, chances are that s/hewill struggle <strong>with</strong> learning in grades four through twelve. Many middle school <strong>and</strong> high schoolstudents lack the ability to use communication skills effectively for the purpose of learning.Teachers <strong>and</strong> parents often assume that these skills will develop by themselves over time. Thefact is that they rarely do.One solution is embedded curriculum, in which learning skills are taught in conjunction <strong>with</strong>course content. Students need to be provided <strong>with</strong> appropriate modeling of language <strong>and</strong> thoughtprocesses, <strong>and</strong>, since this is often not accomplished in the home, then it must be done in theschool. The problem is that most classrooms do not provide this modeling. Faced <strong>with</strong> theubiquitous pressure of st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests, teachers often resort to rapid “covering” of the materialthey are supposed to teach, <strong>with</strong> little regard for whether students are developing appropriatebrain programs for learning, thinking, <strong>and</strong> problem solving. In most schools, the preferredpedagogical techniques are teacher lecture, worksheet skill drills, <strong>and</strong> reading to answer end-ofchaptercomprehension questions. Teachers who use these methods can say that they “covered”what they were supposed to cover in the curriculum. The results are that students perceive schoolas a passive, often boring, learning experience in which they seldom see how different subjects1 Excerpted from F<strong>org</strong>et, Mark A. <strong>and</strong> M<strong>org</strong>an, Raymond F. (1997) A brain compatible learning environment for improving studentmetacognition. <strong>Reading</strong> Improvement, v. 34, no. 4, Winter, 1997.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com5

elate to either reality or to one another, or even how what was learned last week in a givensubject area relates to what was learned this week.Textbooks are valuable tools. Though the textbook should not be the only information sourcein a class, the textbook is an often-neglected or misused tool for learning. The fact is that muchof the content being measured by st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests is to be found in textbooks. The basic themesof a course <strong>and</strong> the vocabulary of the discipline are to be found there.The problem is that, even though many of the questions on st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests requireinterpretive reading, most students are not being exposed to thoughtful interpretation of text.Worksheets <strong>and</strong> end-of-chapter comprehension questions require only the most basic decodingskills to answer. Students who process text through these methods rarely do the kind of readingyou are doing right now – thoughtfully processing the argument as it was logically presented bythe author. Instead, students often begin in the middle or end of the reading, flipping pages back<strong>and</strong> forth to skim for bold print words that might give them the clue as to where they might find“the right answer.”Any person, regardless of age, can perform higher order thinking about even the most abstractideas if s/he has a basic underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the concept. When teachers think that students cannotperform higher order thinking about subject matter, what they do not realize is that the problemreally lies not in the students, but in the students’ preparation for the thinking. Once studentshave conceptualized the basics, they can more readily perform higher order thinking skills aboutthe subject matter. Many teachers practice assumptive teaching – thinking that because theythemselves underst<strong>and</strong> certain concepts, the students will also underst<strong>and</strong> them in the same ways.One important source of course-specific vocabulary <strong>and</strong> basic conceptual information aboutcourse content is a textbook. However, it is important that the textbook be used properly, <strong>and</strong>that other information sources are also used appropriately.A framework of instruction for acquisition of literacy skills along <strong>with</strong> content areaknowledge includes three-steps that facilitate active engagement of students, allowing the brainto function at its highest levels. Before reading, teachers can motivate students by helpingstudents to recall <strong>and</strong> add to their prior knowledge of the topic to be studied, <strong>and</strong> to set their ownpurposes for reading. During the reading, teachers can help students maintain their purposes <strong>and</strong>monitor their own comprehension while acquiring new information <strong>and</strong> new learning skills.After the reading, teachers can facilitate higher-order thinking by students, allowing for thethinking to extend beyond the text.Interaction between student <strong>and</strong> self, student <strong>and</strong> teacher, <strong>and</strong> among students, in the contextof the subject area is critical in developing these abilities. Emphasis is on learning throughguided practice in reading, writing, speaking, listening, <strong>and</strong> thinking. All these are practiced inthe classroom on a daily basis, while students participate in an active process of learning fromtextbooks, from each other, <strong>and</strong> from other materials. Students of all ability levels, in all contentareas, benefit from this form of deeper learning. In addition, the skills acquired in conjunction<strong>with</strong> the content instruction are transferable to other learning experiences because one importantthing being acquired is the process of learning itself. Students thus develop naturally positivebrain programs that they can apply in all future learning situations.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com6

ANTICIPATION GUIDES MOTIVATE STUDENTSThis strategy can be used to guide students through all three phases of the <strong>MAX</strong> teachingframework. It provides Motivation to readers by asking them to react to a series of statementsthat are related to the content of the reading materials <strong>and</strong> also to the students’ prior knowledge.Because students are able to react to these statements, they anticipate or predict what the materialwill be about. Once a student has committed to the statements, s/he will have created ameaningful purpose for Acquisition of new knowledge. Purposeful reading leads to improvedcomprehension <strong>and</strong>, thus, Acquisition of an important comprehension skill. Finally, teachermediatedstudent discussions allow for students to experience EXtension beyond the text. Asstudents work to iron out any differences in interpretation by attempting to come to consensus onconstruction of the author’s meaning, students manipulate ideas in such a way as to experiencehigher order thinking about the subject being learned. This is the point at which application,analysis, synthesis, <strong>and</strong> evaluation level thinking takes place. The result is better underst<strong>and</strong>ing<strong>and</strong> higher retention of subject matter.How to Make <strong>and</strong> Use Anticipation Guides1. Assess the reading material for important concepts.2. Write statements based on the concepts. (Depending on the material <strong>and</strong> the age ofstudents, the number of statements may vary from three to ten or more.) Statements thatare likely to engage students in reading <strong>and</strong> discussion reflect the followingcharacteristics:• All statements are plausible, include important concepts, <strong>and</strong> are phrased in languagedifferent from the way the text is worded.• Some statements include ideas that are intuitively appealing to students, but which willprove to be incorrect upon reading the text.• At least one statement should be written in such a way as to force students to interpretlarge segments of text such as a paragraph or two. This prevents the exercise from turninginto a simple “decoding exercise.”• Some statements are worded in such a way as to provoke critical thinking about the keyconcepts. Rather than true/false statements, they are somewhat vague or interpretational.Based on either the students’ prior knowledge or on the material being presented,students might disagree <strong>with</strong> one another <strong>and</strong> provide some valid evidence for either sideof the argument, both before <strong>and</strong> after the reading.• Some statements may not have a correct answer – it is a good idea to include somestatements to which even the teacher does not have an answer. These can stimulate greatdiscussion leading to deeper underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the subject matter.3. Follow the procedure described on the next three pages.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com7

Anticipation Guide ProcedureStage of <strong>MAX</strong> Lesson Framework: Motivation Acquisition EXtension Lifelong learning skill(s) to be practiced during acquisition:• Using prediction as a means of developing purposes for engaging in reading• Constructing meaning <strong>and</strong> reading critically to clarify interpretation of textMaterials:• Anticipation guides – one per student,• Textbook or other reading,• Transparency of anticipation guideQuick Overview of lesson:1. Predict2. Discuss – small groups3. Silent reading, seeking evidence for interpretations4. Discuss – small groups5. Discuss – whole classDetailed version of lesson:1. Introduce the content of the lesson by posing a hypothetical question, reading a quotation,previewing the text, or some other interest-capturing idea to which students can reactthrough discussion.2. Introduce the skill of prediction. Explain to students that strategic readers most oftenpredict what will be found in the text that they are preparing to read. Explain that it is notso important whether their predictions are right or wrong, but rather that, by predicting,they engage themselves in the reading, thus making the reading easier <strong>and</strong> moreinteresting. If they find out that their prediction was correct, they feel good about it. Ifthey find out that their prediction was not correct, they can react <strong>with</strong> surprise at whatthey actually did find in the text.3. Model use of the skill of predicting. You might wish to describe how strategic readerspredict what they are going to discover in a text by just scanning it first for clues. Youmight model the process by referring to a prediction you made before reading something(a newspaper article or something like that). Discuss how predicting what you were aboutto read helped you to focus on the reading. Explain to students that it does not matter©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com8

whether you are right or wrong in your predictions. By having made predictions, youmake the reading easier to do because while reading, you know what you are looking for.4. Explain to students that, for today’s reading, we are going to use an anticipation guide tohelp us make the predictions so we can practice what strategic readers do. Tell them thatthe prediction guide has many statements on it, <strong>and</strong> that some of the statements will haveevidence in the textbook that supports them, some will have evidence that negates them,<strong>and</strong> some may have evidence that is conflicting, <strong>and</strong> about which students will probablyargue.5. Tell students to place a check mark ( ƒ ) in the space next to each statement that theythink will probably be supported in the reading. Tell them to do this on their own, <strong>with</strong>outlooking at their neighbor’s paper. Tell them not to worry about being right or wrong atthis point. Remind them that they are just making predictions, <strong>and</strong> that once they get intothe reading, they will be able to change their minds about any of the statements if theyfeel they should. Move around the room to see that students are committing to some ofthe statements.6. Tell students to discuss, in their cooperative groups, the predictions that they have made.Ask them to share their logic <strong>with</strong> one another at this point. One student’s priorknowledge may help the others in the group to underst<strong>and</strong> the concepts that are to beencountered. The books remain closed at this point. Move around the room to monitortheir discussions <strong>and</strong> answer any questions they may have. (An alternative to this smallgroupdiscussion is a teacher-led class discussion, especially near the beginning of theyear or when students have very limited prior knowledge.)7. Students should break off the discussions <strong>and</strong> begin individual silent reading at thistime. Remind them that they should keep the prediction guide on the desk for referencewhile they read, <strong>and</strong> that they ought to use inferential thinking while they read. Tell themthat they must interpret what they are reading in order to determine whether a predictionguidestatement should be checked or not, <strong>and</strong> that they must be able to refer to specificparts of the text to verify their beliefs. It is good to have students list page-columnparagraphnotations under the statements they wish to verify or refute. (Their notationsmight look something like this: 251-2-4, meaning that information to support or negate aparticular statement can be found on page 251, column two, paragraph four.) Again,move around the room to monitor progress <strong>and</strong> support students in their work. It is alsogood at this point to read silently along <strong>with</strong> the students, <strong>with</strong> the goal in mind that youmay later need to model some of the thinking that goes into inferring.8. When most students have finished reading, tell them to get back onto their small groupsto discuss again the prediction guide, only now their job changes to attempting to come©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com9

to a consensus <strong>with</strong>in their groups about whether a statement should be checked or not.Here, they compare their various interpretations of what they have read, referring toevidence in the text to support those interpretations. Again, move around the room toassist in this process, making sure that students are referring to the text to support theiropinions. Allow several minutes for the discussions to occur.9. When at least one group has come to a consensus on the prediction-guide statements, usetheir decisions to conduct a whole-class discussion to attempt to achieve a classroomconsensus. Make sure that students are able to support their beliefs either through directreference to the text or through their interpretation of specific text. It is very importantduring this phase of the lesson that the teacher act as a mediator or arbitrator, avoidingtelling students answers. Intellectual ownership must be in the minds of the students asthey collectively construct meaning from the text. Near the beginning of the year, someteacher modeling of inferential reading might be necessary, but students will quickly takeownership of the process, <strong>and</strong> they will surprise you <strong>with</strong> their thoroughness of analysis.10. Ask students to report on their use of the skill of predicting. Say – did the process ofpredicting what you were going to read before reading, <strong>and</strong> discussing it <strong>with</strong> your peershelp you in concentrating on the reading, <strong>and</strong> in comprehending the reading? Did it helpyou focus <strong>and</strong> stay focused while you were reading? (Students inevitably realize at thispoint that, by practicing predicting before reading, they were engaged in the reading,leading to heightened comprehension.)11. Take the opportunity to review <strong>and</strong> reinforce the use of the skill of predicting. Point outto students that they can use the skill in any reading that they do in any subject area toengage themselves, make the reading more interesting by setting a purpose for reading,<strong>and</strong> by keeping that purpose in mind during the reading.12. Continue reflection through a free-write, homework, a quiz, etc.Anticipation Guides: Herber, H. (1978). <strong>Teaching</strong> reading in the content areas (2 nd ed.).Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Readance, J. E., Bean, T.W., & Baldwin, R.S. (1981).Content area reading: An integrated approach. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com10

MotivationAcquisitionEXtensionThe Goal?The teacher motivates students by• linking the day’s lesson tostudents’________ __________,• adding to their prior knowledgethrough sharing <strong>and</strong> discussion.• modeling a _____ to be used.The students cooperatively establishtheir own purposes for reading by• making ___________,• asking ___________, or• anticipating use of the ______.The teacher ____________ guidedpractice in the literacy skill(s).The students read silently to acquirenew knowledge & skills by• maintaining their own __________for reading,• practicing a literacy _____,• gathering written information.In the third phase, The teacher___________ students’ discussions to• _________ meaning from text bymanipulating ideas,• ______ knowledge beyond text bypracticing higher order thinkingskills, <strong>and</strong>• report on success resulting fromthe literacy _____.Activities for the third phase of thelesson: ________________________________________________________________________________________________Making reading/thinking _____ forstudents!©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com11

This page is intentionally left blank.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com12

<strong>MAX</strong> TEACHING WITH READING AND WRITING:A RATIONALE AND METHOD 2The only way to learn how to read is by reading, <strong>and</strong>The only way to get students to read is by making reading easy.Frank Smith (1988), Joining the Literacy ClubLiteracy, in the most basic sense of the word, is the ability to read <strong>and</strong> write. But such anability entails so much more than simply deciphering combinations of letters on a page orplacing words on paper in a certain order. Literacy involves listening, thinking, <strong>and</strong> speaking insuch a way that information <strong>and</strong> ideas are processed <strong>and</strong> communicated to the benefit of self <strong>and</strong>society.Few would deny the importance of literacy skills in either the academic world or thebusiness world. Yet, schools beyond the early grades often do not see the role they could play indeveloping <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ing literacy skills in students, <strong>and</strong> so they relegate that duty to others.St<strong>and</strong>ardized tests such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provideevidence of this failure to stimulate students to achieve higher levels of literacy skills. Accordingto NAEP tests, a significant portion of middle grades <strong>and</strong> high school students read at or belowthe basic reading levels.Disparity in Literacy SkillsThe poor performance in reading scores that many American middle <strong>and</strong> high schoolstudents consistently earn on state <strong>and</strong> national tests result not from inadequate test preparationbut from a lack of basic literacy skills that in other times <strong>and</strong> circumstances might have beenlearned at home. It is no surprise that schools situated in upper middle class neighborhoodsconsistently score higher than those in poorer areas, whether rural or urban. The fact of thematter is that children who come from homes in which literacy (the ability to read, write, speak,listen, <strong>and</strong> think well) is valued <strong>and</strong> practiced are the ones who consistently score higher onst<strong>and</strong>ardized tests. These are children who come from homes in which books are commonplace,magazines are found on the coffee table, <strong>and</strong> a newspaper lies on the driveway in the morning.They see their parents using literacy to learn, communicate, <strong>and</strong> conduct business. To suchchildren, literacy skills tend to come easily, <strong>and</strong> thus they score highly on st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests. Onthe other h<strong>and</strong>, children from homes that have little print matter available <strong>and</strong> in which the TV<strong>and</strong>/or siblings are raising the children (often because financial circumstances require theparents, or a single parent, to be away much of the time working two jobs) tend to score lower onthe same tests. Schools can make up for this disparity, but to do so, they will have to rethink howthey teach children.What Do <strong>Reading</strong> Tests Measure?2 F<strong>org</strong>et, Mark A. (2003, in press.). <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> reading & writing: How all teachers can maximizestudents’ underst<strong>and</strong>ing of their subject matter.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com13

We must not be too quick to criticize elementary schools for the job they are doing.Though schools vary in their performance, early grades educators are generally doing a good jobof teaching students to decode print through the use of phonics <strong>and</strong> other methods. At grade four,United States students lead the world in the ability to read (learn). It is by eighth <strong>and</strong> twelfthgrades that a negative disparity is found between the scores of American students <strong>and</strong> those ofother industrialized countries.Tests conducted by the Department of Education’s National Assessment of EducationalProgress show that more than 60 percent of high school seniors in the United States score at orbelow the basic level of reading (as compared to the proficient <strong>and</strong> advanced levels). A scan ofNAEP’s own literature points out that what is being measured in their tests is the ability ofstudents to perform higher order thinking while they read. The manual that NAEP publishes <strong>with</strong>their report every two years suggests that when grade level materials are used, students reading atthe “basic” reading level should be able to “demonstrate an overall underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> makesome interpretations of the text.” Students reading at the “proficient” level should be able to“show an overall underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the text which includes inferential as well as literalinformation.” And students reading at the “advanced” level should be able to “describe moreabstract themes <strong>and</strong> ideas.” In addition, students reading at the advanced level should be able to“analyze [<strong>and</strong>] extend the information from the text by relating to their own experiences <strong>and</strong> tothe world.” (National Center for Educational Statistics, 1998).In other words, what the NAEP is measuring is the ability of students to perform higherorder thinking while learning. The question is, Are we teaching students how to think? Are wecreating the conditions in our classrooms in which students are routinely enabled to analyze,apply, synthesize, <strong>and</strong> evaluate what they read?How Schools Can Help Students Acquire Literacy SkillsWhat can schools do to help middle <strong>and</strong> high school students improve their achievementin learning? The systematic use of reading <strong>and</strong> writing to help students learn their subject matteris one answer. Students who are placed in an environment in which they are allowed to pursuelearning through the means of reading, writing, discussing in cooperative groups, <strong>and</strong> thusmanipulating ideas to construct meaning are finding that learning does not have to be difficult orboring. Rather, it can be fluid <strong>and</strong> engaging—even exciting. What students in such anenvironment learn is that, despite their background or home environment, they can succeed aslearners. A collateral benefit is that, while students in content area classes read, write, <strong>and</strong>discuss in order to learn content, they actually improve the thinking skills directly related tohigher performance in reading <strong>and</strong> writing.What About Students Who Are <strong>Reading</strong> Below Grade Level?<strong>Reading</strong> involves construction of meaning. Modern views of reading suggest that thereader, using the “set of tracks” left by the author <strong>and</strong> relating it to the reader’s prior knowledge,thereby constructs a message. The good news is that students who are reading below grade level,<strong>and</strong> who do not at a given time have the skills to read a piece of text independently, can read textconsiderably beyond their diagnosed reading grade level when they have the support ofcompetent peers <strong>and</strong>/or a facilitating teacher. Students practicing learning through reading in thisway can in fact read text that is as much as four years above their diagnosed reading levels©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com14

(Dixon-Krauss, 1996). The key is having well prepared teachers—teachers who know strategiesto help students (a) interpretively process text <strong>and</strong> (b) work cooperatively to manipulate the ideas<strong>and</strong> themes of the course.Students who have previously been frustrated by their lack of literacy skills find that theyare able to develop appropriate skills <strong>and</strong> strategies that can make all the difference. Themediated literacy instruction, which employs cooperative learning, helps such students gain theability to perform literacy skills autonomously. Stated another way – There is only one way tolearn literacy skills, <strong>and</strong> that is by practicing them…<strong>and</strong> there is only one way to get students topractice literacy skills, <strong>and</strong> that is to make it easy for them to do so. That is what <strong>MAX</strong><strong>Teaching</strong> is all about.How <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> Works<strong>MAX</strong> is an acronym that st<strong>and</strong>s for the three steps of a teaching framework that anyteacher can use. The acronym st<strong>and</strong>s for Motivation, Acquisition, <strong>and</strong> EXtension. It’s a way tohelp all students better learn their subject matter <strong>and</strong> improve their literacy skills. The essentialgoal of teachers who use the <strong>MAX</strong> teaching framework is to level the playing field by raising thebar for all students. This involves creating a classroom environment that provides instruction inbuilding skills to enable improved performance, while at the same time engaging all students inactive learning from textbooks <strong>and</strong> other forms of textual matter.Motivation:(the first step)Much of current research into motivation of students involves two simultaneous <strong>and</strong> oftencompeting drives <strong>with</strong>in the learner – striving for success <strong>and</strong> avoidance of failure (Marzano,2003). What the teacher does in the pre-reading phase is based on the awareness of these twodrives.Each class begins <strong>with</strong> activities designed to motivate students to become engaged in thelearning of content, even if it is content that is difficult or might not otherwise interest them. Thisfirst step is accomplished through the systematic use of both individual <strong>and</strong> cooperative activitiesthat help the teacher…• find out what the students already know about the topic to be studied,• assist students in connecting to <strong>and</strong> seeing the relevance of subject matter,• provide for increased conceptual underst<strong>and</strong>ing for all students,• introduce <strong>and</strong> model a literacy-related skill that the students will use to probe text <strong>and</strong>gather information for development of new underst<strong>and</strong>ings, <strong>and</strong>• help students establish concrete purposes for actively probing the text.It is through carefully guided implementation of all of these components that students whootherwise might not have taken an interest in the learning experience are guided to becomecurious about subject matter <strong>and</strong> to form a plan for finding new information.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com15

Acquisition (the second step)Once students have clear purposes for learning, the teacher facilitates guided practice in thelearning skill introduced in the Motivation stage of the lesson. (The exact skill to be practicedvaries, depending on the needs of the students, the structure <strong>and</strong>/or difficulty of the text, or onother variables.) In the Acquisition phase of the lesson, each student…• silently reads to interpret <strong>and</strong> gather information in writing for later discussion,• actively probes text for acquisition of new content, <strong>and</strong>• works toward acquisition of expertise in the practiced literacy skill.Typically, this part of the class involves silent reading by students as they each gatherinformation to be brought to small-group <strong>and</strong> whole-class discussion after the reading. In somecases, where student reading abilities are uniformly well below the level of the text, the teachermight read all or a part of the text aloud to the class while students read along silently. However,as early in the school year as possible, students should be allowed to practice mature silentreading to gather information through their own interpretations.Frequent systematic guided practice in literacy related skills allows students to acquire theskills <strong>with</strong>out even being aware that they are doing so. Just as a person acquires fluency in alanguage through the immersion process by living for some time in a place where the language isspoken, students acquire complex <strong>and</strong> content-specific literacy-related skills. Acquisition isdifferent than learning – most people who ever tried to “learn” a second language through yearsof course work cannot speak it. Yet people who were given the opportunity to spend lengthyperiods in foreign l<strong>and</strong>s often acquire the language <strong>with</strong>out formal training. It is this lessobservable yet profound form of development that is occurring in a content literacy classroomthrough immersion in reading, writing, speaking, listening, <strong>and</strong> thinking about course content.EXtension:(the third step)The final phase of the lesson framework involves EXtension beyond the text. This takesplace through various activities that might include debate, discussion, writing, re<strong>org</strong>anizing, orotherwise manipulating the ideas that were confronted in the reading. Students meet in smallgroups <strong>and</strong> as a whole class to construct meaning from the text. The teacher, in this phase of thelesson, acts as a facilitator for the higher order thinking that will allow students to (a) synthesizeinformation, connecting new facts <strong>and</strong> ideas <strong>with</strong> what they already knew before the lesson; (b)analyze the knowledge newly gained; <strong>and</strong> (c) think about how to apply what they have learned inreal-world circumstances, or even to make an evaluation of the author’s argument or underlyingintent. It is through such higher order thinking that students develop more completeunderst<strong>and</strong>ings about new content. It is also through such practice in higher order thinking thatstudents develop the skills <strong>and</strong> abilities to perform these tasks on their own as independent lifelonglearners. (Chapter 6 will exp<strong>and</strong> on this phase of the lesson.)The principles underlying the <strong>MAX</strong> teaching framework have been well researched overmany years. The essential components of the use of cooperative learning throughout the first <strong>and</strong>last phases of the lesson, along <strong>with</strong> the systematic introduction of skills in which students aregiven guided practice in the use of language as a tool for thinking, combine to help all studentslearn how to become effective learners <strong>and</strong> thinkers. In addition, the <strong>MAX</strong> teaching framework©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com16

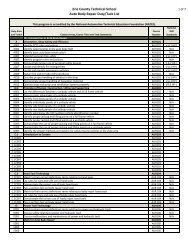

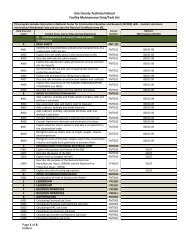

provides a way for upper grade teachers to help compensate for the inadequate language skillsdevelopment that too many children exhibit.The combination of the three daily elements of <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> leads to a classroomenvironment in which support for difficult literacy-related activities is provided throughout thelesson. The likelihood of success in reading, writing, speaking, listening, <strong>and</strong> thinking isenhanced by each of the elements.FIGURE 1Daily Elements of <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong><strong>MAX</strong> SAM CLBefore <strong>Reading</strong>MotivationGetting Ready to Read byRelating Subject Matter toStudent Prior Knowledge<strong>and</strong> Setting PurposeIntroduction<strong>and</strong> Modelingof the SkillWrittenCommitmentDuring <strong>Reading</strong>AcquisitionIndividual Silent <strong>Reading</strong>for Personal InterpretationIndividualGuided Practicein the SkillGatheringInformation forDiscussionAfter <strong>Reading</strong>EXtensionConstruction of Meaning<strong>and</strong> Re<strong>org</strong>anization ofInformation throughDiscussion & <strong>Writing</strong>Reflection onHow the SkillWorkedAttempt toAchieveConsensusBy focusing on a skill – such as paraphrasing, note taking, or re<strong>org</strong>anizing writteninformation, the teacher is reducing the probability in any given student’s mind that the learningexperience will lead to failure. Instead of teaching just subject matter, the teacher is focused onhelping students learn how to learn the subject matter! Risk is also reduced by the use ofcooperative learning, if done properly.Any teacher can improve the probability of students actively participating in cooperativelearning by following a few important steps in the process. It is important that there is a realproblem to be solved. That is to say that the typical worksheet is not a task suitable for activecooperative learning. Appropriate tasks that truly engage students are characterized by posingtrue dilemmas for which multiple solutions exist <strong>and</strong> about which a certain level of ambiguityleads to more than one possible solution. But, even good cooperative learning tasks can fail if notfacilitated properly.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com17

Students should, before even entering the cooperative group, have something in writing towhich they have committed. This gives each student a stake in the process – an idea that can bediscussed or defended even before the learning experience.Once students have gathered information from the reading (or video, lecture, etc.), theirdiscussions will be enhanced by an attempt to come to a consensus on their interpretation of thelearning material. Consensus means each of the students in a cooperative learning group mustagree on an interpretation, <strong>and</strong> this should be attempted first in small groups <strong>and</strong> then as a class.The process of attempting to achieve consensus assures that all students are involved in the coreprocess of reading – construction of meaning. The result is that all participants acquire readingskills <strong>with</strong>out even being aware that they are doing so.How Frequently Should Teachers Use <strong>MAX</strong>?All effective teachers use some form of the three steps that comprise <strong>MAX</strong>. At thebeginning of class, most teachers use some form of an “anticipatory set” to get students thinkingabout the subject matter. The new information is often then “presented” in some format such as alecture, video, teacher-led discussion, or some other way of communicating information. Thepresentation of new information is usually followed by some form of check, such as a worksheetor quiz.Thus, the paradigm shift in using <strong>MAX</strong> as a framework of instruction is easy for mostteachers since, <strong>with</strong> <strong>MAX</strong>, they now become facilitators of their students’ active learningthrough the use of reading, writing, speaking, listening, <strong>and</strong> thinking in the middle <strong>and</strong> finalphases of class. The teacher acts as a “master learner” among “apprentice learners” in aclassroom wherein the focus is on acquisition of knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills through guided practice inusing literacy skills to process new subject matter.Using literacy skills to process new underst<strong>and</strong>ings can easily become the central focusof a classroom <strong>and</strong> can be used as a way to learn any new information. The variety of testedstrategies available to teachers is enormous. Researched <strong>and</strong> proven strategies abound. Thus,practicing literacy skills to learn should not be a once-a-week or once-a-month activity. It canbecome the routine of a classroom in which students are engaged in making personal meaningfrom text <strong>and</strong> discussion every day.Which Teachers Should Teach This Way?Teachers who use the <strong>MAX</strong> teaching framework do not need to be reading specialists.Academic <strong>and</strong> vocational teachers from the elementary grades through high school only need torecognize that by using the concrete tools of text <strong>and</strong> student writing, along <strong>with</strong> teachermodeling <strong>and</strong> cooperative learning, they can help their students routinely achieve higher orderthinking about their subject matter. Staff development in using these strategies is accomplishedthrough h<strong>and</strong>s-on demonstration <strong>and</strong> modeling. Any teacher can use these techniques. Afterparticipating in staff development in using reading <strong>and</strong> writing to learn, most teachers areimmediately able to employ a variety of reading/writing strategies in their classrooms. Recentresearch has demonstrated that students can improve their reading levels by two or more yearsover a six month time period when exposed to learning through these strategies (Greenleaf,Schoenbach, Cziko, & Mueller, 2001). Which teachers would not want to teach this way?©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com18

Interactive Cloze <strong>Reading</strong> ProcedureStage of <strong>MAX</strong> Lesson Framework Motivation ƒ Acquisition ƒ EXtension ƒLifelong learning skill(s) to be practiced during learning:• Predicting to create purpose for reading• Contextual definition of vocabulary termsQuick Overview of Lesson:1. Give to students a copy of the Interactive Cloze passage that you have created to summarize the reading<strong>and</strong> focus on key vocabulary terms.2. Students individually guess by writing (preferably in pencil) the terms they think will best complete thepassage.3. Small group discussion to compare guesses – students may change some.4. Silent reading to determine better responses from the text.5. Small group discussion to attempt a consensus on correct terms.6. Large group discussion to achieve class consensus.Detailed version of lesson:1. Introduce the content of the reading by posing a hypothetical question, reading a quotation, previewing thetext, or some other interest-capturing idea to which students can react through discussion.2. Give each student a copy of the interactive cloze sheet. Tell them that all strategic readers who have someprior knowledge about a topic make predictions about what they are about to read before reading. Tell themthat you have provided a worksheet that will allow them to predict certain key vocabulary terms that theywill find in the reading they are about to do. Tell them to attempt to guess what words go in the spacesprovided on the worksheet – based on their own prior knowledge of the topic. Let them know that manyclues may be found in the passage itself <strong>and</strong> that they should use as many clues as they can find. Thisactivity should be done individually – not as a cooperative group.3. Model the thinking required, by reading the first few lines <strong>and</strong> allowing for conjecture by the class as towhat terms might be used in one or two of the spaces. Discuss the relative merit of words offered bystudents. Use this opportunity to discuss connotations. Let students know that there will only be one wordper space, <strong>and</strong> that they should pay special attention to punctuation, verb endings, modifying words, etc. asclues to help them predict the correct words.4. Move around the room to see that all students are attempting to predict the words that go in the spaces. Youmay need to help some of the students link prior knowledge to what they are attempting to do. Allowsufficient time for many of the students to finish their predictions, but do not wait for all students to finishbefore the next step.5. Now put students into their cooperative learning groups. Groups of three or four are appropriate. Remindthem not to look at the reading at this point, but tell them that they should compare their predictions <strong>with</strong>one another. Let them know that they may change any prediction if they feel that another person in thegroup has a better one for a specific space on the worksheet. Tell students that it is important that they©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com19

explain to the others in their group why they chose the response they did for any given word. This way theyare helping each other to exp<strong>and</strong> the prior knowledge base they have. (At the same time, they are increasingthe purposeful nature of the reading to come since they are anticipating more as a result of theirdiscussions.)6. Again separate students from their groups <strong>and</strong> tell them that it is time to do the reading. Let them know thatthey should read silently, from the beginning to the end, seeking terms that the author used or terms that aremore appropriate that the ones they have predicted. Again, move around the room to facilitate this process<strong>and</strong> keep students on task.7. When most students have finished reading, put students again into groups to compare their findings <strong>and</strong> toattempt to come to consensus on the best vocabulary terms that fit into the spaces on the interactive clozesheet. Facilitate this by moving about the room to help in discussions, but try not to give answers. Helpstudents to weigh the merits of various terms as they work out a consensus.8. Ask students to report on their use of the skill. Ask them to raise their h<strong>and</strong> if they agree that, by makingpredictions on the cloze form <strong>and</strong> discussing their predictions <strong>with</strong> other students before the reading, thatthey found that their comprehension was improved over the normal way they might have read if they werejust assigned a regular worksheet..9. When at least one group has finished, you might take that group’s terms <strong>and</strong> fill them in on a transparencyof the cloze passage. Then conduct a class discussion to bring the whole class to consensus. Be sure to usethis opportunity to focus on connotations of words, praising <strong>and</strong> otherwise discussing the alternatives thatstudents present as opportunities to reinforce thinking about words.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com20

NAME_________________________________________ DATE_____________________THREE LEVEL STUDY GUIDE: <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong>: Rationale & MethodINSTRUCTIONS: Scan the statements on this study guide before reading pages 7-13. Then,during or after reading, place a check mark ( ƒ ) in the space next to each statement <strong>with</strong> whichyou agree. Be sure to be able to refer to the text to support your choices whether you agree <strong>with</strong>a statement or not.LEVEL I: RIGHT THERE ON THE PAGE___1. Learning subject matter through reading, writing, <strong>and</strong> discussion is engaging <strong>and</strong> helpsstudents to improve their own thinking skills.___2. <strong>MAX</strong> is an acronym that st<strong>and</strong>s for motivation, acquisition, <strong>and</strong> extension.___3. Teachers who use reading <strong>and</strong> writing in their classrooms to help students learn theirsubject matter should be reading specialists or language arts teachers.___4. Silent reading allows students to interpret new information in their own personal ways.LEVEL II: READING BETWEEN THE LINES___5. <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>and</strong> writing is not so much about the ability to manipulate print as it is about theability to think in a sophisticated way.___6. Critical thinking is thinking that questions its own validity.___7. Heterogeneous grouping is an important characteristic of a literacy oriented classroom.___8. Some students who are able to read aloud <strong>with</strong> tremendous fluency are not really goodreaders.___9. Literacy skills – like a person’s first language – are acquired through meaningful use.LEVEL III: READING BEYOND THE LINES___10. “Teach a child what to think <strong>and</strong> you make him a slave to your knowledge. Teach a childhow to think <strong>and</strong> you make all knowledge his slave.”___11. Most students would perceive <strong>MAX</strong> teaching to be a less threatening learningenvironment than a more traditional classroom.___12. If a significant number of teachers used literacy skill practice in their classrooms most ofthe time, more students would better learn their subject matter.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com21

This page is intentionally left blank.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com22

Three-Level Study GuidesThree-Level Study Guides (Herber, 1970) are very similar, in some ways, to anticipationguides. They are composed of a list of statements to which students react during <strong>and</strong> after thereading of some piece of text. Therein lies the chief difference: though it is sometimes useful tohave students predict about the reading through an anticipatory scan of 3-level guides, just as ifthey were anticipation guides, in most cases, they are better used during <strong>and</strong> after the reading.Thus, they are Acquisition <strong>and</strong> EXtension level activities, <strong>and</strong> require some pre-readingMotivation activity to start the lesson. (I usually use a preview of the reading.)Three-Level Study Guides are made up of statements that relate to the reading. Students, asthey do <strong>with</strong> anticipation guides, read to find evidence that proves or disproves the statements.The three different levels are composed of statements that the teacher has arranged into the threecategories of “literal interpretation,” “inferential interpretation,” <strong>and</strong> “synthesis or applicationlevel interpretation” of what is being read. Appendix 3 has several 3-level study guides asexamples.By using these guides, students are explicitly empowered to perform higher order thinking.Once explained to students, they know that it is OK to think outside of the lines in the text. Theyknowingly stretch their interpretation, <strong>with</strong> the knowledge that the teacher is encouraging thisbehavior. Unfortunately, this is the opposite of what is normally expected in many classrooms.All too much effort is placed on listening to how the teacher interprets what is important, orlooking for answers to place in spaces on worksheets, all at the literal level of interpretation.To make a three-level study guide, Richardson & M<strong>org</strong>an (2003) recommend creating leveltwostatements first, then looking back through the text to find level-one statements that canpoint students in the direction of discovery of the ideas in level two, <strong>and</strong> finally adding levelthreestatements to help students to think beyond the text. In creating level-two statements, I findthat the methods mentioned in chapter 10 of this book for making anticipation guides are helpful.Each statement is a plausible rephrasing of a key idea in the text, <strong>and</strong> the statement is designed toprovoke thoughtful discussion <strong>and</strong>/or argument.I recommend creating three-level study guides by using three different pieces of paper, eachlabeled 1, 2, or 3. Have them on the desk while reading the piece of text you are planning to use<strong>with</strong> the students. As you read, focus on level two, but jot down statements on any of the threesheets of paper that represent each of the three levels of thinking. It is easier to do it this waybecause the concepts do not always appear in the sequence you wish. I do focus on level-twostatements, but as often as not, I recognize level one or three statements while seeking level two.Literal statements are the easiest to make because you are taking the statements pretty muchfrom the text.Level two statements involve “reading between the lines.” They are inferential statements –those things that you would like students to infer from the reading if they were reallyaccomplished readers, but you know they would not probably spot those things on their own. Ifind that, by referring to the five bullets (on page 7 of this packet) on how to make anticipationguide statements, I am able to make good level-two statements for a three-level guide.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com23

Level three statements are your opportunity to apply what you know about Bloom’sTaxonomy. These involve “reading beyond the lines.” Level three statements get students tohave to extend beyond the text by performing thinking that has them synthesize, apply, analyze,or argue. At this level, you might make statements that relate the reading to what was learned inthe previous chapter or something in the news. It is also good to use famous adages at level three.Using three-level study guides is one more way to get students to perceive themselves aspersons who can <strong>and</strong> do perform higher order thinking over what they read. Again, the keys toaccomplishing this are the concrete props of the text <strong>and</strong> the 3-level study guide that the teacherhas constructed to facilitate the process.Classroom Procedures for Three-Level Study GuidesLifelong learning skill(s) to be discussed <strong>with</strong> students <strong>and</strong> practiced during the process:• <strong>Reading</strong> critically to clarify interpretation of text• Thinking at the literal, inferential, <strong>and</strong> application/synthesis levelMaterials:• 3-level guides – one per student,• Textbook or other reading,• Transparency of 3-level guideQuick Overview of lesson:1. Motivation activity to start discussion – PreP, fact storm, Previewing, etc.2. Introduction of thinking at three levels3. Silent reading, seeking evidence for interpretations4. Discuss – small groups5. Discuss – whole classDetailed version of lesson:1. Capture the students’ interest. Introduce the content of the reading by posing ahypothetical question, reading a quotation, previewing the text, or some other interestcapturingidea to which students can briefly react through discussion.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com24

2. Introduce the skill of thinking at three levels. It is a good idea at this point to modelthinking at three levels by doing so on a topic that was recently covered in class. This canalso bring students up to pace <strong>with</strong> a brief review. Show students how, after reading aparagraph or two, you literally interpret what it says. Then show how you might infer ameaning into it. Then think out loud about how it might apply in the real world. Let themknow that this is the way they will be thinking concerning today’s reading, but that youhave helped them do so by separating the statements on the three-level study guide ontothe three levels of thinking.3. Ask students to scan the statements on the study guide to see what they are about. Tellthem that, unlike an anticipation guide, they do not have to check the statements theythink to be true ahead of time. Instead, they will do so during or after the reading. Allowa few moments to scan the 3-level guide.4. Explain to students that, for today’s reading, we are going to use a different type of studyguide to help us comprehend the reading, so we can practice what strategic readersroutinely do to make reading more underst<strong>and</strong>able. Tell them that the three-level studyguide has many statements on it, <strong>and</strong> that some of the statements will have evidence inthe textbook that supports them, some will have evidence that negates them, <strong>and</strong> somemay have evidence that is conflicting, <strong>and</strong> about which students will probably argue.5. Students should begin individual silent reading at this time. Remind them that theyshould keep the three-level guide on the desk for reference while they read, <strong>and</strong> that theyought to use all levels of thinking while they read. Tell them that they must interpret whatthey are reading in order to determine whether a statement should be checked or not, <strong>and</strong>that they must be able to refer to specific parts of the text to verify their beliefs. It is goodto have students list page-column-paragraph notations under the statements they wish toverify or refute. (Their notations might look something like this: 251-2-4, meaning thatinformation to support or negate a particular statement can be found on page 251, columntwo, paragraph four.) Move around the room to monitor progress <strong>and</strong> support students intheir work. It is also good at this point to read silently along <strong>with</strong> the students, <strong>with</strong> thegoal in mind that you may later need to model some of the thinking that goes intothinking at the different levels.6. When most students have finished reading, tell them to get into their small groups todiscuss the three-level guide, attempting to come to a consensus <strong>with</strong>in their groups aboutwhether a statement should be checked or not. Here, they compare their variousinterpretations of what they have read, referring to evidence in the text to support those©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com25

interpretations. Move around the room to assist in this process, making sure that studentsare referring to the text to support their opinions. Allow several minutes for thediscussions to occur.7. When at least one group has come to a consensus on the three-level study guidestatements, use their decisions to conduct a whole-class discussion to attempt to achieve aclassroom consensus. Make sure that students are able to support their beliefs eitherthrough direct reference to the text or through their interpretation of specific text. It isvery important during this phase of the lesson that the teacher act as a mediator orarbitrator, avoiding telling students answers. Intellectual ownership must be in the mindsof the students as they collectively construct meaning from the text. Near the beginningof the year, some teacher modeling of higher order thinking <strong>and</strong> reading might benecessary, but students will quickly take ownership of the process, <strong>and</strong> they will surpriseyou <strong>with</strong> their thoroughness of analysis.8. Ask students to report on their use of the skill of thinking at three levels. Say – did theprocess of thinking at literal, inferential, <strong>and</strong> application/synthesis levels help you tocomprehend what you read more than when you are doing a worksheet? Did it help youfocus <strong>and</strong> stay focused while you were reading? (Students inevitably realize at this pointthat, by practicing higher order thinking while reading, they were engaged in the reading,leading to heightened comprehension.)9. Take the opportunity to review <strong>and</strong> reinforce the use of the skill of thinking whilereading. Point out to students that they can use the skill of thinking at the literal,inferential, <strong>and</strong> application levels in any reading that they do in any subject area toengage themselves, make the reading more interesting by setting a purpose for reading,<strong>and</strong> by keeping that purpose in mind during the reading.10. Continue reflection through a free-write, homework, a quiz, etc.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com26

Cornell (Two-Column) Note TakingThe Cornell method of note taking (M<strong>org</strong>an, F<strong>org</strong>et, <strong>and</strong> Antinarella 1996; Pauk, 2001) is astudy skills strategy that can be taught <strong>and</strong> utilized in all content areas. It is a strategy that can beused <strong>with</strong> reading text or listening to a lecture. It is also a note-taking method that is required ofstudents in many, if not most, law schools <strong>and</strong> medical schools – a fact that speaks well for itseffectiveness as a tool for retention of great quantities of information.Good notes are the product of strategic reading or listening. The Cornell method helpsstudents <strong>org</strong>anize information in a useful format, rank the importance of various elementscontained in the reading <strong>and</strong> systematically study the information that has been evaluated <strong>and</strong><strong>org</strong>anized. The student recognizes a main idea <strong>and</strong> contributing points from which this theme isgenerated. The student then can judge how much detail to record in light of the assigned orexpected outcome of the reading. In this way, the student gains control <strong>and</strong> becomes moreefficient in the learning process.By necessity, this note-taking system moves the student from a passive reader/listener to oneactively involved <strong>with</strong> comprehension. It is this linkage to thinking <strong>and</strong> comprehension thatresults in long-term learning. The strategy helps the student become a better learner by acquiringmetacognition skills. The student underst<strong>and</strong>s that the notes are a skeletal representation thatmust be dealt <strong>with</strong> correctly to keep the whole picture in correct context.Good note taking forces interaction <strong>with</strong> the learning experience, leading to acquisition of theability to be metacognitive in learning situations. Studies show that students consider note takingto be an essential learning skill for success in secondary school <strong>and</strong> college. Other research <strong>with</strong>students indicates that a good set of notes is very significant in academic success. Mostimportantly for middle <strong>and</strong> high school teachers is that Cornell notes can be a very productivenightly homework assignment. This will be discussed below.Underst<strong>and</strong>ing the SystemCornell (or 2-column) note taking is a system that divides a page of loose leaf paperdifferently than the way it comes from the store. Most loose leaf paper has a red margin aboutone to one <strong>and</strong> a half inches from the left edge of the paper. In 2-column note taking, the notetaker ignores that margin <strong>and</strong> draws a new margin about 1¼ inches to the right of the originalmargin, dividing the paper into 1/3 <strong>and</strong> 2/3 sized sections. Then, the note taker ignores the redmargin, writing all the way to the left edge of the paper. The only thing that goes on the left sideof the paper is a main idea. So there is a good deal of space on the left side of the paper betweenmain ideas (all the easier to spot the key points). On the right (2/3) side go all the details relatingto the main idea. These are the details that are to be recalled. This note taking system is©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com27

especially appropriate for reading notes, <strong>and</strong> it can become a nightly homework assignment tomake these notes about what was read in class that day.Objectives 9/5Format of Cornell Notes:1. Describe the format of twocolumnnotes2. Explain how to use them tostudyFormatStudyingMain idea goes on the left side of thenotes. Details that relate to the mainidea go on this side of the page.Typically there are anywhere fromtwo to six or seven main ideas oneach page of looseleaf paper. Theprocess is repeated for each of themain ideas about which the student istaking notes.This is useful as a study tool sincethe student can cover the right side ofthe page or Fold th page over to tryto recall the details relating to themain idea.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com28

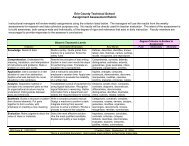

The Way ItShouldn’t Be• Students have noconnection to whatthey are to learnbecause they did notread the homeworkassignment <strong>and</strong> theydo not connect to theirprior knowledge.• Teacher has studentscopy down 15-20vocabulary words <strong>and</strong>look up definitions forthem.• Round-robinreading.• Students are told tocopy down notes theteacher has provided.• Students fill inspaces on worksheetscreated by textbookpublisher.• Students are told thatthis material will be onthe test on Friday.• Little or no verbalinteraction occurs, <strong>and</strong>no one learns verymuch.The Way ItSometimes Is• 10-20% of studentshave completed theassigned reading.• Most students haveno clue about theassignment or theconcepts they shouldhave learned fromthe text.• Teacher attemptsto teach concepts bylecture, questions,probes forunderst<strong>and</strong>ing,video, notes, etc.• All students havesome level ofconceptualunderst<strong>and</strong>ing.• None haveimproved theirlearning skills. Theteacher did all thework!• The hiddenmessage is thatstudents don’t haveto read – the teacherwill tell them all theyneed to know.The Way ItIs <strong>with</strong> <strong>MAX</strong>• Teacher helpsstudents link priorknowledge to theday’s lesson.• Students establishtheir purposes forlearning.• Students activelyprobe text in attemptto satisfy their needfor underst<strong>and</strong>ing.• Students help oneanother constructunderst<strong>and</strong>ing ofsubject matter.• Intelligentdiscussion occurs<strong>with</strong> all studentshaving completeknowledge base <strong>with</strong>which to work.• All students usethe vocabulary of thediscipline.• Students performmeaningfulreflection forhomework.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com29

DAILY LESSON PLAN: TOPIC ___________________ DATE __________OBJECTIVES:MATERIALS:KEY VOCABULARY TERMS:Motivation:Acquisition:EXtension:©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com30

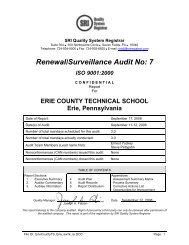

Three Daily Elements of <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong>Four Components of Successful Cooperative Learning:1. Individual Written WorkCommitment2. Small Group Work*Consensus3. Large Group DiscussionMediation/Arbitration4. A Real Problem to be Solved*heterogeneous groups_____________________________________________________________________________Skill Acquisition Model:1. Introduce <strong>and</strong> model a skill.2. Provide guided practice in use of the skill.3. Have students report on their use of the skill <strong>and</strong> how it helped them to learn the content._____________________________________________________________________________<strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> FrameworkHelpingstudents strivefor successMotivation Acquisition EXtensionReducing Threat-freeanxiety over opportunity to Individual Higher orderpossible interact <strong>with</strong> practice in a thinkingfailure textlearning skillRepetition ofimportantconcepts <strong>and</strong>vocabulary• <strong>Writing</strong> to think <strong>and</strong>commit to ideas• Cooperative discussiontoo Determiningpriorknowledgeo Building priorknowledge• Focus on a learningskill• Setting concretepurpose for reading• Silent purposefulreading• <strong>Writing</strong> to gatherinformation for furtherdiscussion• Individual practice inthe learning skill• Individualmanipulation ofconcepts <strong>and</strong>vocabulary• Cooperative discussion<strong>and</strong>/or debate tocollectively constructmeaning• Low-threat immediatefeedback• Individual <strong>and</strong> groupmanipulation ofvocabulary & concepts• <strong>Writing</strong> to re<strong>org</strong>anizeinformation• Analysis, synthesis,application, evaluationof reading material• Reflection on the useof the learning skill©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com31

PRINCIPLES OF READING/WRITING TO LEARN:APPLYING THE <strong>MAX</strong> TEACHING FRAMEWORKMOTIVATION1. Motivation comes from two competing forces – striving for success <strong>and</strong> avoidance offailure. Before the reading, teachers must explain & model how to process textsuccessfully.2. In order to underst<strong>and</strong> new knowledge, students must be aware of what they alreadyknow through their own study <strong>and</strong> experiences.3. In order to focus their attention on important concepts, students must have clear purposesfor reading <strong>and</strong> must predict <strong>and</strong> anticipate what will be learned.4. In order to grasp concepts which are difficult or beyond present knowledge <strong>and</strong>experiences, students must have a conceptual base before encountering new vocabulary.5. In order to become active seekers of knowledge, students must be motivated <strong>and</strong>personally interested in the subject to be studied.ACQUISITION: In order to comprehend what is read, students should:1. Become active participants in seeking information from text.2. Consciously apply <strong>and</strong> adjust their reading strategies to the dem<strong>and</strong>s of text.3. Underst<strong>and</strong> text structure <strong>and</strong> <strong>org</strong>anization.4. Monitor their own comprehension.5. Use visual techniques to assist them in grasping overall structure of ideas.6. Be involved during reading in developing, refining, correcting, <strong>and</strong> supporting their ownpredictions <strong>and</strong> hypotheses.7. Be able to rephrase ideas read in their own language.EXTENSION: In order to extend their underst<strong>and</strong>ing of concepts <strong>and</strong> retain what islearned, students should be able to:1. Restructure the information from text into a framework that includes linking it <strong>with</strong>existing knowledge <strong>and</strong> experiences <strong>and</strong> thereby exp<strong>and</strong>ing their schema for the ideas inthe text.2. Look for ways to apply new knowledge in terms of what is reasonable <strong>and</strong> valid.3. Evaluate <strong>and</strong> think critically about new knowledge in terms of what is reasonable <strong>and</strong>valid.4. Raise questions to clarify misunderst<strong>and</strong>ings or extend their underst<strong>and</strong>ing beyondinformation in the text.5. Recognize when information given is insufficient <strong>and</strong> new questions need to be raised.6. Relate information to other subject area courses, their own experiences, <strong>and</strong> current worldevents <strong>and</strong> issues.7. Use information to creatively solve problems.8. React to information through discussions <strong>with</strong> other students <strong>and</strong> through their ownwriting.©2004 <strong>MAX</strong> <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Reading</strong> & <strong>Writing</strong>, 6857 TR 215, Findlay, OH 45840, 404-441-7008 http://www.maxteaching.com32