ifda dossier 50 - Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation

ifda dossier 50 - Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation

ifda dossier 50 - Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

international foundation for development alternatives<br />

fundacibn intemacional para altemativas de desarrollo<br />

fondation Internationale pour un autre developpement<br />

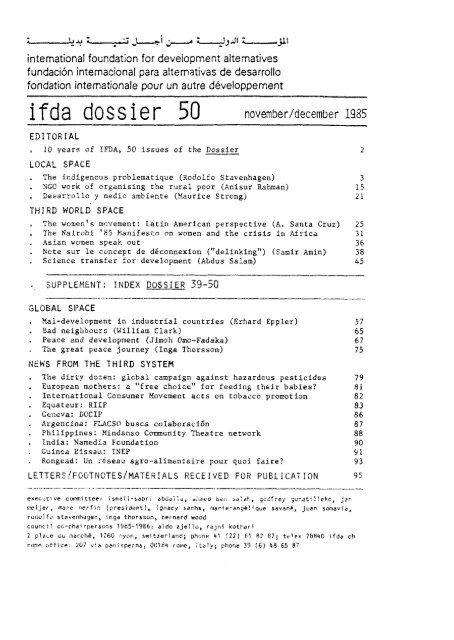

<strong>ifda</strong> <strong>dossier</strong> <strong>50</strong><br />

EDITORIAL<br />

10 years of IFDA, <strong>50</strong> Issues of the Dossier 2<br />

LOCAL SPACE<br />

. The Indigenous problematique (Rodolfc Stavenhagen)<br />

. NGC work of organising the rural poor (Anisur Rahmanj<br />

. Debarroll0 y medio ambiente (Maurice Strong)<br />

. The women's movement: Latin American perspective (A. Santa Cruz) 25<br />

. The Nairobi '85 Kanifesto on women and the crisis in Africa 3 1<br />

. Asian women speak out 36<br />

. Note sur Ie concept de dGconnexion ("delinking") (Samir Amin) 3 8<br />

Science transfer for development (Abdus Salam) 4 5<br />

, SUPPLEMENT; INDEX DOSSIER 39-<strong>50</strong><br />

GLOBAL SPACE<br />

--------p<br />

-p---<br />

. Mal-development in industrial countries (Erhard Eppler) 5 7<br />

Bad neighbours (William dark) 65<br />

. Peace and development (Jimoh Omo-Fadaka) 67<br />

. The great peace journey (Inga Thorsson) 75<br />

NEWS FROM THE THIRD SYSTEM<br />

The dirty dozen: global campaign against hazardous pesticides<br />

European mothers: a "free choice" for feeding their babies?<br />

International Consumer Movement acts on tobacco promotion<br />

Equateur: RIIP<br />

Geneva: DOCIP<br />

Argentina: FLACSO buses colaboraci6n<br />

Philippines: Mindanao Community Theatre network<br />

India: Namedia <strong>Foundation</strong><br />

Guinea Bissau: INEP<br />

Rongead: Un reseau agro-alimentaire pour quoi faire?<br />

LETTERS/FGCITNOTES/MATERIALS RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION 95<br />

e x e v e cormittee: ismaii-saDt -i abddXo, o;,i~wa be,. :?ii:ah, gcci'rey gunat:!!&?, j~r.<br />

meijer, marc nerfin (president), 'lgnacy sachs, nldrie-an9el"que savane, juan somavia,<br />

rcdotfo stavenhagen, inga thorsstin, bernard wood<br />

cour'c":? co-chairpersons 1985-1966: aido ajellc, raJni kothari<br />

2 place du narch6, 1760 nyon, ~witzerland; phune 41 !2?) 61 82 82; tt-'m 78840 <strong>ifda</strong> ch<br />

row office: 207 via par~isperna, 00184 rtime, :t.aIy; phone 39 (6) 48 65 87

ifd: <strong>dossier</strong> <strong>50</strong> . november/decernber 1985 edi toria1<br />

10 YEARS OF IFDA, <strong>50</strong> ISSUES OF THE DOSSIER<br />

ue sec zb'i's as an oppoi>tur.ity to present the --- Dossier to its many r<br />

reidars l sce insert between pcgs~ tit? and 57).<br />

~ e ~<br />

The ether- IFUA publication, the SUNS, appears daily in Kyon and Rome<br />

shse ISSO (its 1 flovember issue 'bears 7iUi,354). It atcenpts to cover,<br />

from a Third Vortd point of vieu, the north-3uth and development coop-.<br />

eraticm debate i*: the United :Sations fora, especially in Geneu~, Rome<br />

and .Vau York, ¥i veil as the Third V,'orldfs effoz~ts towards collect-ivc.<br />

self-reliaice. It is a speciatizcd publication circulated to szibsar-ibsrs<br />

only (specimen cop$ and taz-ift's are available qmn request).<br />

IFDA. a7.80 engages in specific* projects. The largest one uas the third<br />

*?,:em project> earl-ied our .fron 1977 to lS8d ct tke request and with<br />

the support of the Dutch and Ncruegi-an gover~nents. Its pzdyose uas to<br />

ore"; to 7zu: aator: and unhear.2 voices the discussion on the Limited Uation.'<br />

Interwtiod Development Strategy for the 80s. IfLustr&i:,<br />

IfWe netuork-ing method3 some 60 inscitut-Lone arid 630 indiuidua'is from<br />

all reqicns participated in 1^3 s'tuiies, repcvts, seminars and othei-<br />

activit iee, I-CS principal Zo~y-tem<br />

resu2.t i8 the Dcssier itself> shich<br />

uas orig

i fda <strong>dossier</strong> <strong>50</strong> . november/decernber 1985 local space<br />

THE INDIGENOUS PROBLEMIQUE<br />

by Rodolfo Stavenhagen<br />

El Calegio de Mexico<br />

Apartado 20671<br />

Mexico DF 10740, Mexico<br />

Resume: L'auteur dgfinit les peuples indigenes come les habitants orl-<br />

ginels dun territoire qui, 2 la suite des circonstancr-s historiques<br />

(conquzte et/ou colonisation) ont perdu leur souverajnete et sont subor-<br />

.donn6s 2 une sdciSt6 plus vaste et 5 un Etat our lequel 11s n'ont pas de<br />

pouvoir. I1 examine les facteurs qui ont contribug i la prise de con-<br />

science de la probl6mat.lque indig?:~e, notamment la dGcolonisation,<br />

l'auto-determination reconnue par les Nations Lrnieo come un des droits<br />

de l'houune, la sensibilisation aux violations des droits de I'home, les<br />

contacts entre peuples indigenes et 'civilisation moc'erne', la re-d6cou-<br />

verte des valeurs indigenes. I1 analyse ies origines de la problematique<br />

indigene, principalemeni en Am6rique du Nord et du Sud (oh se trouvent<br />

la moitie des populations rkpondant la definition sugg-ii6a). I1 aborde<br />

ensuite les principaux problgmes contemporains des peuples indigenes,<br />

dont Ie principal ast probablement celiii de la cullure et de l'identite<br />

face aux ethnocidss. Iefauteur pose 2 cet Sgard un certain nombre de<br />

questions sp6ciflques cencrees sur la dilemme existentiel auqu-il sont<br />

confrontes ies peuples indigenes. 11 ne a'agit pas de refuser la change-<br />

ment culturel, mais de pernettre aux culc-ires indigenes de repondre aux<br />

defis modernes en developpant leur propre potential et de contribuer<br />

ainsi 2 la culture universelle.<br />

Resucen: El autor define a 10s pueblos indfgenos como habitintes origl-<br />

nales de un territorio, 10s cuales. en consecuencia de circunstancias<br />

historicas (conquista y/o colonizaci6n) han perdido su soberanfa y estzn<br />

subordinados a una sociedad mayor y a un Estado sobre el. cual no tienen<br />

nivgGn poder. Examina 10s factores que han contribuido a1 tema de con-<br />

ci-incia de la problemStica indlgena, especialmante la decolonizaci6n, la<br />

autodeterminaci6n, reconocida por las Naciones Unidas como uno de 10s<br />

derechos del hombre, 10s contactos entre les pueblos indigenes y la "ci-<br />

vilizsci6n modernat', el re-descubrier-to de 10s valores indigenes. Ana-<br />

liza lor orfgenes de la problsmatica indtgena, principalmenta en America<br />

del Norte y del Sur (en donde se encuentran el <strong>50</strong>: de las poblaciones<br />

quo corresponden a la definition sugerida). Luego aborda 10s principales<br />

probl.emas conterapor5neos de Los puebLori indfge~ws, de 13s ~^niles el<br />

principal es probablementa el de la cultura y el de la identidad frente<br />

a 10s genocidios. El autor plantea preguntas especificas centradas scbre<br />

el dilema existencial a1 que hacen frente 10s pueblos indigenes. No se<br />

trata de rehusar ei cambio cultural. pero de peraltar a las culturas<br />

indigenas ue responder a los desaflos modernos, desarrollando su proprio<br />

potenc.ial y contribuyendo as1 a la cultura universal.

Rodolfo Stavenhagen<br />

THE INDIGENOUS PROBLEMATIQUE<br />

Who are the Indigenous?<br />

Indigenous populations may be defined as the original inhab-<br />

itants of a territory who, because of historical circumstan-<br />

ces (generally conquest and/or colonization by another peo-<br />

ple), have lost their sovereignty and have become subordina-<br />

ted to the wider society and the state over which they do<br />

not exercise any control.<br />

Frequently the issues faced by indigenous populations are<br />

dealt with within the framework of minority problems. But<br />

whereas many indigenous peoples in the world constitute in-<br />

deed ethnic minorities within the wider society, in some<br />

cases they are numerical majorities, who do not, however,<br />

enjoy a corresponding share of political and economic power.<br />

That is why indigenous peoples distinguish their problems<br />

from those of other ethnic, linguistic, religious, national<br />

or racial minorities, and consider that they should be dealt<br />

with separately. Some indigenous organizations insist that<br />

they should be called "First Nations".<br />

The concept of indigenous peoples sometimes overlaps or is<br />

used indiscriminately with other terms such as natives, abo-<br />

riginals, "autochtones" or tribal populations. But again,<br />

while most tribal peoples may be considered as indigenous,<br />

not all indigenous peoples should be considered as tribals.<br />

In the Americas, the indigenous populations are known as<br />

Indians.<br />

Indigenous populations are found in different parts of the<br />

world and their number may be placed at probably close to a<br />

hundred million. The ma-jority are concentrated on the An-.eri-<br />

can continent, both North and South (around fifty million),<br />

but they also include the Australian aborigines, the New<br />

Zealand Maori, the Sami people in Scandinavia, the Inuit of<br />

the Arctic region, and sundry other groups. Before independ-<br />

ence, the peoples of Africa and Asia were referred to as<br />

"natives" by the colonial powers, but this terminology is of<br />

course no longer in use. On these continents, the minority<br />

tribal peoples often find themselves in situations similar<br />

to those of the indigenous in other parts of the world.<br />

Public aEenzss about in

of the earth. Many indigenous peoples consider their situa-<br />

tion as being similar to that of the colonies and demand<br />

similar attention to their problems. The concept of internal<br />

colonialism is frequently used to describe the relationship<br />

between indigenous peoples and the State to which they be-<br />

long.<br />

2) The principle of self-determination of peoples is a major<br />

international human right, recognized by the United Nations.<br />

But even though the UN has been very clear that this princi-<br />

ple should not be interpreted as applying to minorities<br />

within the framework of established independent states, in-<br />

digenous peoples consider that the principle of self-deter-<br />

mination should by all rights also apply to them.<br />

3) In countries where violations of human rights have been<br />

recorded, and where indigenous populations are established,<br />

these have often been singled out as particularly vulnerable<br />

victims of human rights violations. Such violations have<br />

been brought increasingly to the attention of world public<br />

opinion through national and international agencies.<br />

4) Indigenous peoples have for many generations lived out<br />

their lives on the margins of the economic mainstream. As<br />

the economic frontier advances and as indigenous peoples<br />

have come increasingly into contact with "modern civiliza-<br />

tion", their problems have come to public attention and have<br />

often become major political issues.<br />

5) In many parts of the world, economic development programs<br />

such as river basin development schemes, land settlement<br />

projects, highway construction, mining activities, the<br />

tri.nsformation of tropical forests into cultivateable acreage<br />

or pastures (as, for example, in the Amazon basin) have<br />

negatively affected the life chances of indigenous population~,<br />

and they have become the victims rather than the beneficiaries<br />

of these transformations.<br />

6) In a period of increasing world violence and inter-state<br />

conflicts, the borderland regions frequently inhabited by<br />

indigenous peoples in some parts of the world, have become<br />

the object of considerations of "national security", and the<br />

indigenous have often lost their own security in the pro-<br />

cess; or else they may be manipulated by outside powers for<br />

purposes other than their own best interests. These issues<br />

are often reported as major political news.<br />

7) As so many development strategies which were furiously<br />

pursued during the last few decades are now considered to be<br />

failures, many people have taken a second look at indigenous<br />

val-ues and life-styles in their search for development al-<br />

ternatives. The cultural values of peoples not yet wholly<br />

absorbed by industrial civilization (as happens to be the<br />

case with a number ot indigenous peoples around the world) ,<br />

are looked at with more respect and attention than was the<br />

case earlier when technological improvement was automatical-

ly deemed superior and desirable for the more "backward" so-<br />

cieties.<br />

8) The worldwide tourism explosion has broken down borders<br />

and distances. Tourism and folklore (ethnic arts, the Fourth<br />

World, Club Maditerranse, etc.) are powerful attractions .and<br />

have brought the most isolated "tribal", the most downtrod-.<br />

den "indigene" within reach of an airline excursion fare<br />

ticket or at least within the turn of a television knob of<br />

the average "Northern" household.<br />

Some theoretical limitations<br />

The points outlined above have contributed to the renewed<br />

visibility of indigenous peoples at the present time. To be<br />

sure, the countries of the West (and I would say th2 North,<br />

in general) have not yet overcome the exotic fascination<br />

that the "Primitives" around the world exert on their ina-<br />

gination. For a long time the idea of progress, or more re-<br />

cently, developmental theory, have more or less tacitly as-<br />

sumed that economic growth and corresponding social change<br />

would do away with indigenous popi-ilations, much to the cha-<br />

grin of ethnographers, folklorists, romantics and tourists.<br />

Some lamented their passing, most however welcomed such<br />

changes as necessary and desirable for modernization and<br />

progress to take place.<br />

Thus, in recent years, concern with the situation of indigenous<br />

peoples has been relegated to sorre special ized brzi;: -<br />

ches of the social sciences. The major paradigms of social<br />

science thinking did not consider the indigenous as worthy<br />

of their attention. Social theory (and particularly its 2evelopmental<br />

variety) was more concerned with major issues<br />

such as economic growth, urbanization and industrialization,<br />

the power of the state and political process, militarization<br />

and conflict, social classes arid social movements, rather<br />

than with such "marginal" social groups as the i.ndiqer.cj-i",<br />

peoples.<br />

The model of the nation-state which Europe has been able to<br />

impose on the rest of the world - through revolution and<br />

empire - is usually thought of as ethnically and culturally<br />

homogeneous though in fact this is by no means always the<br />

case, not even in Europe. Within this model there is hardly<br />

any place for indigenous peoples as separate from ths dcminant<br />

majority (in some cases, minority). The re-emergence of<br />

indigenous peoples as a world issue at the present time requires<br />

some basic rethinking of a number of accepted<br />

"truths" in contemporary social science.<br />

ORIGINS OF THE INDIGENOUS PROBLEMAT~QUE"<br />

Throughout human histo~y, peoples have shifted and rni?r^r-ed<br />

and come into contact with each other. Contact may have been

Deacefui or violent; different peoples may have coexisted<br />

with each other peacefully, or they may have fought and<br />

quarrelled over territory or access to resources. Usually<br />

the weaker peoples have been pushed by the more aggressive<br />

ones into ecoioqically less rewarding areas.<br />

Before the advent of modern technology and the world capitalist<br />

system, ethnic and cultural differences between peopie's<br />

w2re linked to different ways of life and to relatively<br />

se1.f-contained social systems. It is often difficult to det-I-,ine<br />

who were the original inhabitants of a given territory,<br />

for those groups who appeared as nati~e inhabitants at<br />

the time of the European colonial expansion may in turn have<br />

displaced earlier settlers.<br />

Whereas the situation is fairly clear-cut regarding the ori-<br />

ginal claims of American Indians as against the European<br />

settlers who conquered them and set up their own political<br />

systems, or for example the very similar process in Austra-<br />

lia and New Zealand, it is more difficult for, say, the Ai-<br />

nus to validate their claim of "originality" vis-a-vis the<br />

Japanese, or the, inhabitarts of the Chi ttagong H i l l Tracts<br />

in Bangladesh in relation to the lowland Perigalis who have<br />

been moving into their traditional territory. In Sri Lanka,<br />

the original Vedic people have practically disappeared, and<br />

both Tamils cind Singhalese now claim original territorial<br />

right?.<br />

The "indiqenous problematique" of course arises in full force<br />

after the establishment of the modern colonial systems.<br />

But here it soon acquires the characteristics of the "colonial<br />

question", which in turn achieves its solution through<br />

decolonization and the granting of political independence to<br />

forrr.erly de~endent territories.<br />

North America<br />

p---<br />

The first ma jcr movement tor political independence took<br />

place on the Mieri.can continent, in the "Thirteen Colonies"<br />

and later in Latin. America at the beginning of the nine-<br />

teenth century, that is, before the great imperialist push<br />

by Europe into Africa and Asia. In what became the United<br />

States, the native American Indians were pushed off their<br />

lands by the advancing settlers and political independence<br />

belonged to the white settlers, not to the Indians. A series<br />

of so-called Indian wars consolidated the power of the set-<br />

tlers, now masters of the land, during the nineteenth cen-<br />

tury. The independent US siqried a number of treaties with<br />

the major Indian nations, thus in fact recognizing the lat-<br />

?.er's sovereignty. But these treaties were quickly violated<br />

by the US government, driven as it was by its "manifest des-<br />

tiny" to overwhelm and destroy anything that stood in the<br />

way of the expanding capitalist system. Today the surviving<br />

Indian nations demand respect for these treaties and appeal<br />

to both Constitutional and International law in defence of<br />

their original rights which they claim are being systemat-

ically violated by the United States Government. The US In-<br />

dian organizations have taken the initiative to form the<br />

International Indian Treaty Council, in order to join forces<br />

with other similarly placed peoples (such as in Canada, for<br />

example) in the defence of their rights.<br />

In contrast to the US government, the government of Canada<br />

has gone a long way to meet the demands of its own indige-<br />

nous populations.<br />

Spanish America<br />

In Spanish America, the situation evolved somewhat differ-<br />

ently. Here, except for a small number of special cases<br />

(such as the Mapuche in southern Chile, for example) the<br />

Indian populations were early incorporated into a system of<br />

servile labour to the benefit of the colonial overlord, and<br />

a complex set of laws, rules and decrees (known collectively<br />

as Legislacion de Indias) evolved during three centuries of<br />

Spanish rule, which fixed the Indian's subordinate status in<br />

the colonial society. Here again, as earlier in the United<br />

States of America, the struggle for political independence<br />

from Spain was waged by the local upper classes who were<br />

ethnically indistinguishable from their Spanish rulers. Not<br />

only that, but they were very conscious about wishing to<br />

maintain and perpetuate the cultural model of the colonial<br />

society after independence. Of course, there were also dis-<br />

sident and libertarian voices among the leaders of the Spa-<br />

nish American revolutions of the early nineteenth century,<br />

but in the end the victors were conservative landowning<br />

classes, who up to the middle of the twentieth century (and<br />

in some countries to the present time) have been able to<br />

maintain their political power and to impose their concep-<br />

tion of the nation-state.<br />

The emerging model of the new political society faithfully<br />

reflected the basically agrarian class structure. Though<br />

slavery and serfdom were formally abolished in most coun-<br />

tries, and all inhabitants were legally considered as free<br />

and equal citizens, the Indian peasant masses were absent<br />

from the polity and of course not represented in government.<br />

In fact the existence of Indians as ethnically distinct en-<br />

tities was never formally recognized. By the middle of the<br />

nineteenth century, a number of so-called liberal reforms<br />

abolished what little protection the Indian communities had<br />

been able to preserve from colonial times, particularly re-<br />

garding collective land rights.<br />

The expanding market economy, coupled with political libera-<br />

lism and individualism required free land and free labour<br />

and these were not available as long as the Indian popula-<br />

tion~, still a majority in most Spanish-American countries<br />

during the early twentieth century, remained tied to their<br />

traditional cultures and social structures. The mere exist-<br />

ence of "backward" Indians was considered by the riiling<br />

elites and their ideologues (schooled in social Darwinism

and positivism) as a drag on progress and development. The<br />

model to be followed by these elites, which were France and<br />

England in the nineteenth century, soon became the United<br />

States, whose economic and geopolitical interests became<br />

dominant in Latin America by the twentieth century.<br />

The fostering of European immigration was considered fash-<br />

ionable and good politics in a number of countries, and in<br />

some of these the Indians were either entirely or almost<br />

wholly exterminated to make way for the new European set-<br />

tlers. Biological mixing of the populations (actually lead-<br />

ing to "whitening") was deemed to be desirable, in line with<br />

the prevailing racist ideologies of the times.<br />

That these ideologies have not entirely disappeared is shown<br />

by one South American militaristic government's plan a few<br />

years back to settle white emigrants from Zimbabwe in the<br />

predominantly Indian country. A world-wide outcry and the<br />

resistance of the Indians themselves led the dictatorship to<br />

abandon the project.<br />

After racism went out of fashion as official government po-<br />

licy, the catchword became "national integration" or "as-<br />

similation", the idea being that directed culture change<br />

(through educational and linguistic policies primarily)<br />

would make the Indians disappear and turn them into "true"<br />

nationals of their respective countries. The onus of poverty<br />

and backwardness was placed squarely on the Indians them-<br />

selves and the notions of development and modernization be-<br />

came synonymous with the cultural and social transformation<br />

of the Indian populations. These ideas were incorporated<br />

into official policy and sanctioned by intergovernmental<br />

organizations and international congresses and conferences.<br />

The Indians themselves, of course, were never consulted.<br />

In other parts of the world, wherever European settlers came<br />

into contact with native peoples who were not organized as<br />

state-societies and who were not able through sheer demo-<br />

graphic presence or political and military power to counter-<br />

weigh Europe's colonial expansion, the lot of the indigenous<br />

became desparate.<br />

In the Caribbean they were practically exterminated shortly<br />

after European settlement and the ensuing labour scarcity<br />

for the colonial enterprises was filled with imported slave<br />

labour from Africa. In Tasmania the British colonists com-<br />

pletely wiped out the natives. In Australia, due to heavy<br />

European settlement along the Coast, the Aboriginal popu-<br />

lation was decimated and the economic bases of their lives<br />

almost completely destroyed. A similar fate befell the indi-<br />

genous peoples of the Philippines, those who resisted Chris-<br />

tianization and incorporation into the Spanish mold (similar<br />

to what the Spaniards set up in America), and whose descen-

dants, many of whom are tribal peoples, coilst.it'

today claim their right to possess such a territory, defined<br />

in political and administrative terms.<br />

C) As natural resources other than land become increasingly<br />

important ir today's econoniy, outside interests exert enor-<br />

mcus pressures on ir.diger-ous societies, even in those cases<br />

where the rights over land and t:erritory may have been ade-<br />

quately defined. Thus the attempt by private companies or<br />

governments to exploit such resources whi-ch have tradition-<br />

ally been under the control of indigenous societies as, say,<br />

timber and fishing grounds, run into indigenous resistance.<br />

Much more dangerous to the survival of the indigenous has<br />

been the discovery and extraction of oil deposits, uranium<br />

and other mineral resources on their traditional. lands,<br />

which of course require considerable investments and techno-<br />

logical capabilities.<br />

7) In most cases the indigenous populations lack or at least<br />

are notably deficient in such basic social services as<br />

schools, water supply, el~czricity, communications, health<br />

services, adequat,e housing and other adjuncts of modern ci-<br />

viiization which many gavel-rments have taken it upon them-<br />

selves to provide to their populations. The indigenous are<br />

often the last sector of the popul.at:ion to be so serviced.<br />

8) Many ind-~qenouc, peoples have long ceased to be the renote,<br />

isolated, self-sufficient communities which early traveliers,<br />

anthropologists, missionaries and government officials<br />

described in their reports. Interaction between the<br />

indiaenous and members of the wider society have always taken<br />

place to some extent. However, in many countries the<br />

expanding economic frontier and improved transportation networks,<br />

Yave opened avenues for increased and more intensive<br />

relationships between the indigenous and the non-indigenous.<br />

An -~mport.ant element of such relationships is labour relations,<br />

particularly in those parts where a decreasing land<br />

base and demographic pressure have forced the indigenous<br />

labour force to seek employment outside their communities.<br />

It should be remembered that a major objective of colonial<br />

policy was to force indigenous labour to work for the colonial<br />

enterprise. While the more brutal forms of labour recruitment<br />

(including slavery, forced labour, different forms<br />

of serfdom, of which the indigenous have always been the<br />

victims), were abolished in the independent post-colonial<br />

states, different forms of labour relations existing today<br />

are clearly unfavorable to, and exploitative of, the indigenous<br />

work force. In many parts of South America virtual<br />

serfdom of Indians on the large landholdings is still cominonplace.<br />

Where salaried labour is the norm.. wages are often<br />

lower for the indigenous than among the rest of the population<br />

and minimum labour protection norms are not respected.<br />

9) Indigenous peoples usually speak a language other than<br />

the national or official language or languages of a given<br />

country. In fact, their linguistic distinctiveness is often

taken as a criterion for the definition of the indigenous<br />

social groups as such. Whereas among some groups the vernac-<br />

ular language continues to be spoken actively (or written<br />

and read, wherever a script exists, which is sometimes the<br />

case among tribal peoples in Asia but hardly anywhere else),<br />

among other groups the native languages tend to disappear.<br />

In many countries, the replacement of the indigenous lan-<br />

guages by the national or official ones is the stated pur-<br />

pose of government policy. In other countries, however, the<br />

reverse may be true. Some governments have adopted policies<br />

of bilingual education and purport to preserve the native<br />

languages. The preservation of indigenous, and minority lan-<br />

guages in general, has been recommended by international.<br />

conferences under the auspices of UNESCO. Still, the general<br />

and apparently irresistible tendency at the present time is<br />

for indigenous languages to lose importance and slowly dis-<br />

appear, particularly when they lack a script, when the par-<br />

ticular linguistic group is small, and when government poli-<br />

cy is not favorable to the maintenance of these languages.<br />

One of the many issues facing indigenous linguistic groups<br />

is whether to deploy efforts in order to maintain and, in-<br />

deed, develop their own languages, or whether to submit to<br />

linguistic acculturation and integrate linguistically into<br />

the wider society.<br />

10) What can be said for language, holds true for other as-<br />

pects of indigenous culture as well. Indeed, the possibility<br />

of the preservation of their own culture (understood in the<br />

widest, anthropological sense of the term, as a shared set<br />

of institutions, values, symbols and social relationships<br />

which gives any social group its identity and distinguishes<br />

it from other similar groups), is probably the essential<br />

question on which hinges the survival of indigenous peoples<br />

as such in the world today. Are indigenous cultures fated to<br />

disappear? Are they no longer relevant to the needs of con-<br />

temporary society? Does progress and development among indi-<br />

genous peoples necessarily imply the disappearance of their<br />

cultures? Does the expansion of the "national society" imply<br />

the "deculturation" of indigenous peoples and their integra-<br />

tion as a marginal underclass into the socio-economic sys-<br />

tem? Does "nation-building", the desired goal of so many of<br />

the Third World's leaders today, require the disappearance<br />

of the indigenous cultures? Are these cultures an obstacle<br />

to economic and social development, as so many observers<br />

have stated over the last few decades? Is it not possible to<br />

"build nations" and respect the minority cultures that have<br />

flourished for so long in the backwaters of the world's<br />

great civilizations? Is it possible to build multi-national<br />

societies (as some of the world's larger states are commit-<br />

ted to do) in which indigenous cultures may find their due?<br />

Is not the preservation of any group's culture a necessary<br />

ingredient for its members' well-being?<br />

These are not only rhetorical questions beggin3 rhetorical<br />

answers. These questions point to the serious dilemmas that

indigenous peoples face in the modern world. They require<br />

the attention of governments and the international conunu-<br />

nity, as well as of the indigenous peoples themselves.<br />

11) The loss of land and language, the perilous weakness of<br />

indigenous cultures in the face of external onslaughts, ca-<br />

norily be understood within the framework of indigenous lack<br />

of power. Perhaps a constant feature of indigenous society<br />

in relation to the wider polity is its powerlessness. The<br />

indigenous have always been denied real and effective polit-<br />

ical participation and they have been sheared of whatever<br />

power they may have possessed before conquest and their usu-<br />

ally forced integration into the national state. Actually,<br />

for the indigenous peoples, "national integration", the of-<br />

ten stated goal of modern states, has meant loss of sove-<br />

reignty and political impotence. Many of their current prob-<br />

lens stem from the fact that up to very recently the indige-<br />

nous peoples have been effectively excluded from the politi-<br />

cal cecision-making process. A recurrent demand of indige-<br />

nous organizations at the present time is political partici-<br />

pation and power over all matters which directly concern<br />

them and the rejection of traditional paternalistic atti-<br />

tudes by overbearing governments and non-indigenous groups<br />

and agencies who intervene in their affairs. A growing de-<br />

mand among the indigenous peoples in different. parts of the<br />

world is the right to self-determination, which the UN has<br />

in principle recognized to all "peoples".<br />

CULTURE AND IDENTITY<br />

Perhaps the fundamental question relating to indigenous<br />

peoples today, as pointed out in paragraph 10) above, con-<br />

cerns the problem of culture and identity. Indigenous cul-<br />

tures, of course, have never been static and unchanging. But<br />

culture change has accelerated over the last few decades, to<br />

such a degree that many observers question whether indige-<br />

nous cultures will be able to survive at all with their own<br />

identity beyond the end of the present century. The danger<br />

to indigenous cultures comes from many quarters; mainly, of<br />

course, national government policies of integration or assi-<br />

milation through the school system and linguistic policies;<br />

then the impact of Christian missionary activities which<br />

perhaps more than any other single factor has contributed to<br />

the destruction of indigenous cultures around the world,<br />

whether in Africa, Asia or Latin America. More recently,<br />

labour migrations and changes in economic activity have pro-<br />

duced transformations in cultural values and life-styles.<br />

The penetration of the mass-media in indigenous areas<br />

(radio, cinema 2nd television) has contributed to the dis-<br />

semination of other, alternative cultural models which un-<br />

dennine the established, traditional cultures.<br />

The process of the systematic destruction of indigenous cul-<br />

tures has been termed "ethnocide". More often than not it<br />

is a deliberate policy by the dominant ethnic group or

groups who control state power, and history has shown that<br />

it has been used by governing classes not only against indi-<br />

genous populations but against "undesirable" ethnic groups<br />

in aeneral. It refers not only to a process of culture<br />

change and assimilation, which of course has always taken<br />

place to some extent wherever an4 whenever different ethnic<br />

groups interact. within the framework of the wider society,<br />

but also to the systematic negation of an ethnic group's<br />

cultural identity by the state.<br />

This ethnic denial may take a number of forms, from the sim-<br />

pie, official denial that subordinate ethnic croups exist. at<br />

all, to the suppression or neglect of statistics referring<br />

to the minority ethnic yroups, to the prohibition of the use<br />

of native languages in schools and public places, to the<br />

forcible change of names and other symbols of ethnic iden-<br />

tity, and to multiple forms of official and unofficial, open<br />

and hidden discrimination of which so many indigenous groups<br />

are the permanent victims.<br />

Ethnocide, particularly when it is internalized by members<br />

of the indigenous groups themselves, turns into sentiments<br />

of inferiority and self-hate, lack of dignity and self-res-<br />

pect and into feelings of despair, hopelessness and insecur-<br />

ity. Many members of indigerious populations who are forced<br />

to emigrate from their communities and cultures into the<br />

hostile environment of the wider society, become members of<br />

that marginalized underclass which characterizes so many<br />

Third World societies today. Next to genocide; ethnecj.de is<br />

the single major destructive force of indigenous peoples.<br />

Undoubtly, culture changes are inevitable and perhaps in<br />

many cases necessary and even desirable from many points of<br />

view. Progress and development - however these terms may be<br />

defined - require the transformation c the old and the iri-<br />

troduction of the new. Both social evolution and social re-<br />

volution rest on the proposition that established cultures<br />

must and will change.<br />

What is at issue here is not the need for change and trans-<br />

formation but the question whether indigenous cultures can<br />

change and adapt to the new challenges of the modern world<br />

without losing their identities; whether indigenous cultures<br />

can respond dynamically, through the development of their<br />

own potential, and thus be able to make their own contribu-<br />

tions to national and world cultures. This is what indiqe-<br />

nous organizations have been saying and demanding; but it<br />

requires specific government policies to achieve these ends,<br />

as well as political action by the indigenous groups them-<br />

selves.

NGO WORK OF ORGANISING THE RURAL POOR ; THE PERSPECTIVE<br />

by Anisur Rahrnan*<br />

36, Grand Montflsuri<br />

1290 Versaix, Geneva, Switzerland<br />

T\is note sorts* some reflect-ions stimlqted bv i~teractio?; u-bth the<br />

1. NGO work of organising the ri-ral poor can have several<br />

different objectives. These w~ll be discussed under four<br />

different headsings.<br />

Economic upliftment<br />

2. This means raising the incomes of the poor, giving them<br />

greater stability of income and some social security or in-<br />

surance against unforeseen situations, old age problems,<br />

etc. If this were the only or the principal objective, effi-<br />

cient "external delivery system" coupled with an internal<br />

group saving scheme is a good way of achieving this. Exter-<br />

nal delivery can be in the form of credit, technology, and<br />

expertise. The group saving scheme takes care of the social<br />

security objective.<br />

3. But emphasis on the external delivery approach con-<br />

flicts with the other objectives discussed below.<br />

Human development<br />

4. Creativity is a distinctive human quality, and the hu-<br />

man development objective aims to develop the creativity of<br />

the people. Creation is the product of thinking and action -<br />

i.e. of articipation. This consists of investigation, re-<br />

flectionp(analysis), decision-making, and application of<br />

decision (action). Reflection upon action (review, evalua-<br />

tion) gives men and women the sense of creation and thus the<br />

sense of having developed as human beings.<br />

S. Human development is a process of &-development -<br />

outsiders cannot develop the rural poor. Outsiders can have<br />

a role, however, of stimulating and assisting this develop-'<br />

ment. This can be done by initiating and stimulating self-<br />

investigation and reflection by the rural poor; by stimula-<br />

ting them to take their own decisions and action, and to re-<br />

*Member of the IFDA Council.

view and evaluate them themselves. The process may be as-<br />

sisted by external inputs (of ideas, points of view, mate-<br />

rials) which the people can internalise or absorb in their<br />

self-development process without being overwhelmed by them.<br />

6. Special questions of human development arise for poor<br />

women. They have a doubly sub-human status. To liberate<br />

their creativity (as also to liberate themselves from male<br />

domination and male oppression) they need to think and act<br />

independently of their male folk to whom they are held to be<br />

subordinate. This requires separate base organisations or<br />

poor women which may collaborate with organisations of poor<br />

men at higher levels to promote common interests.<br />

Achieving social and economic rights<br />

7. This means elimination of economic and social oppres-<br />

sion and injustices and achieving equity in the use of pub-<br />

lic resources. This implies the exercise of collective power<br />

of the poor, and often implies struggle.<br />

8. Judicious struggle is conducted by assessing relative<br />

strengths, and by challenging oppressers/exploiters when<br />

sufficient strength is acquired so as to have a reasonable<br />

possibility to win. The role of outsiders is not to make<br />

this assessment for the poor, but to make them aware that<br />

this assessment is necessary, and to bring to them knowledge<br />

and considerations relevant in this assessment. Also to help<br />

develop a consci~usness among the poor which sees short run<br />

failures as a learning process upon which subsequent strate-<br />

gy is to be built. A struggle is never lost if constructive<br />

lessons are drawn from its failure - the process then moves<br />

forward even through a conscious decision for temporary re-<br />

treat.<br />

9. One role of outsiders in the context of this objective<br />

is to bring to the poor knowledge of what their rights are -<br />

by law, by national policy and by international agreements<br />

and conventions, etc.<br />

10. The question of right to public resources is particu-<br />

larly important in relating this objective to the objective<br />

of economic upliftment. An NGO which brings credit to the<br />

rural poor indefinitely, detracts from the need for more<br />

equitable use of the public credit system - it does not make<br />

sense that the poor's credit needs should be met by "volun-<br />

tary agencies" obtaining resources from special donors while<br />

the public credit system continues to serve the rich. (The<br />

same applies to other public resources). An NGO may only<br />

bring credit to a group of the poor for a brief period, to<br />

demonstrate that the poor are creditworthy, and to develop<br />

among them confidence and ability to handle outside credit.<br />

Simultaneously, the poor should be made aware of their right<br />

to receive credit from the banking system, and of how this<br />

system works. The NGO should aim to withdraw its credit ope-<br />

ration for any single group early, leaving the group to now

.1oqotiate tor credit from the banking system with their organised<br />

strength and m~nagement ability. In this negotiation<br />

a l s ~ tile ?GO may assist, by helping develop contacts and by<br />

:'.e

15. This applies to external credit as well as LC other<br />

deliveries. The tota'. supply of credit for upliftnient cf the<br />

poor is and will remain, limited. 'Soft' credit projects for<br />

the poor which provide ready credit indefinitely to a linitod<br />

nurr.bei- of project qrc,'.;ps take these grc'ups away from the<br />

hsrd ~trv-ggle fcr eccnc~lic upliftrient which che broad mosses<br />

of the poor have to undergo. This would create 'privileged'<br />

groups among the poor and weaken their motivation to pdrtizipate<br />

in the broader strcggle for overall social and instit'~tiona1<br />

change.<br />

16. Social transformation requires transfer of social power<br />

1'rom the present dominating non-producing class to the class<br />

of direct producers, and this transfer is a political process<br />

to be led only by a competent political organisation.<br />

However, successful social transformation, which includes<br />

social reconstruction, is much more than the: mere act of<br />

forilial transfer of political power: it requires a social<br />

p:jychol~gy, culture and capability of sel-f-reliant econt7nic<br />

and social effort. If this is significar,fcly lacking at the<br />

time of transfer c power, people wLli continue to wait upon<br />

deliveries from above, ancl rhe leadership will fail to lead<br />

s d<br />

reconstruction without a massive inflow of external<br />

Lesources and eventual submission again to external intei-<br />

ests.<br />

7 . A corollary ot se-l f-reliant grass-roots (people's) effcrt<br />

is reliance on people's own - knowledge. Examples of sociai<br />

change exist where transfer of macro power has beer.<br />

di-h-iex-ec in the nan~c- cf direct prcduce:-s, but ~.ew pobez has<br />

been appropriated by another class of non-p^.oducers - a<br />

ciaas ct professionals - who have possessed ~.cri~poly uvez<br />

iievelopmer~t knowledge and expertise. Direct producers who<br />

have been rncbili sed for dccompl;' shing a transfer of pc-nrG2r<br />

have submitted tc this class from out cf a sense of intcl-<br />

ler:tsal inferiority, not having developed the needed cor.f~-<br />

dence in their own knowledge and abilities? and in their own<br />

ability to choose from amonq available o'dtside knowledge and<br />

expertise, for their own development. The result becomes a<br />

return to the delivery mentality which must eventually bri.".q<br />

back dependence 02 external resour:ces and hence control.<br />

There is no self-reliant way of development without primary<br />

reliance on people's resources including their own kriow-<br />

J edqe, and professional know ledge has to pli:.y a co~pJ.e~ent-<br />

?.ry but not dominating role in such development.<br />

18. A part of seIf-reliant effort cofisists cf co-~ective<br />

economic cooperation. By this means scares resources, ski?.la<br />

arid t-yr:nts are ~,se:d tc tencfit r.ct u few -,ri,,-ileqed j.?t'.i~i.-<br />

. .<br />

6ualc L-:c sll those %h.: p,:n-t-.ci?cilt. ii- .inch c~c~.fc;..it-i.~'ii~.<br />

T'nroucfh this process resources thi^s (?et 'augmerlte'-' . Practice<br />

cf collective economJ-c coopsrati.cn and collective emnomic<br />

management develops skills and experit-nce in s'dc'k collective<br />

work which should ke regarded as a:: impsrta:it asset<br />

created in the "wc'ir.b of the old order" , f'. "r self-reliant<br />

ecoriomic reconstruction of society.

19. With this perspective in view, work with the; poor which<br />

seeks to dev.?iop their creativity primarily through their<br />

own collective effort, giving emphasis to both the people's<br />

self-reliant thinking and actlori thr~ugh which collectivk<br />

action and c~nsciousness both keep advancing, would be creating<br />

positive assets for the task of social transformation.<br />

1 Fcr some NGOs ¥a Least, a greater :larity of objectives<br />

is necessary for a sharper direction of their work.<br />

2. The chosen objectives, and their rationale, shculd be<br />

discussed with the "target groups". They should be asked to<br />

reflect why development effort in the country has been a<br />

failure, notwithstanding so-called "learned" men bcing in<br />

Aarqe They may not inidally grasp all the' issues, b1.it.. L<br />

?.'road picture of the macro si~-u.^t-i3n shou'l:? be qiven to them<br />

- e.g. the man-land ratio and tht- ldnd distribution sit:uation;<br />

the. national. poverty pict~~r?; the extreme de'pendence<br />

of the count.ry on foreign resc'uri.?o an3 ye+, the inabiliky ~f<br />

such heavy flow of external resources t-o develop thy coui:-<br />

try, and why; the "basket case" image of the cr~untry.<br />

there is 3 n-ie'i tu shock the people into a sense of self-<br />

esteem,<br />

3, The peapie should h? asked to deliberate what fchey wantto<br />

do in this overall context, a/id how the EGO can help<br />

them.. They ~tioald be asked to forvalate their own iiarnedi-ate<br />

objectives, and for collaboration with the NCO these should<br />

b--s consistent with the ohectives fomul.ited by the NGO,<br />

4. There -should be ?ducational sessions to make the target<br />

groups aware of their rizhts by law, gn.vernnie:it policy, int~rnational<br />

cor!vi?r~i_-i.on'3, etc- .<br />

5. From the very b&

er percentage of profit into their group fund; to those ini-<br />

tiating collective economic projects; to those engaged in<br />

production which may be combined with trade in self-produced<br />

goods rather than pure trade. This policy should be discus-<br />

sed with the people, and the rationale explained. As discus-<br />

sed, credit by an NGO to the poor should be seen as a tempo-<br />

rary measure, to be replaced early by credit from the bank-<br />

ing system and/or from group saving funds.<br />

8. The people must periodically evaluate their own experi-<br />

ence and review their progress collectively, draw lessons<br />

from successes and failures, formulate future courses of<br />

action based on past experience, and formulate advice to the<br />

NGO staff as well for achieving agreed objectives. They<br />

should be encouraged to document, store and disseminate<br />

their on-going experience for progressive advancement of<br />

their collective knowledge based on their collective effort.<br />

They may be assisted by NGO staff, local educated youth,<br />

school teachers, etc., to document the results of their in-<br />

vestigation and review ("participatory research") in simple<br />

language; they should also be encouraged to use their cultu-<br />

ral traditions (e.g. kabi-gan, drama, ballads) to document<br />

and disseminate these, and to take their experiences thein-<br />

selves to other groups and villages.<br />

9. In areas where there is a past history of coliect-ivc-<br />

effort by the poor, this history should be collected (by the<br />

participatory process, in which the main researcher will be<br />

the people, assisted if necessary by others) 2nd discussed,<br />

and lessons drawn from them as guide to current. effort. In<br />

new areas where work is to be initiated, this should be the<br />

very first task (except in cases where c3elvir;g into history<br />

of past struggle may create special difficulty for work to<br />

be initiated).<br />

10. Closely following people' S periodic review of their<br />

work, NGO workers will undertake their o1.r periodic collec-<br />

tive review, keeping clearly in view the chose~i oblertives<br />

of their work.<br />

11. It will be valuable to bring out a bulletin which will<br />

periodically print the people's as well as PIGO workers' re-<br />

views of on-going work. The bulletin should be oriented to<br />

print not just "stories." but analytical reviews of o~'-cjoin$<br />

work in the light of the objectives of the work, tr high-<br />

lighting action and experiences most conducive to proniotioii<br />

of these objectives, and to analysing failures to draw cc.~i-.<br />

structive lessons from them. Articles in the bulletin shc~niri<br />

be read and discus~ed in al.' base orqanist"?tions.<br />

12. Needless to say, the NGQ shc'uld work so as to pioqres-<br />

sively .make itself redundant, to any qroup or set of' groups<br />

with which it has been workina intensive.Iy.

PROLOGO A UN LIBRO DE PABLO BIFANI<br />

DESARROLLO Y MEDIO AMBIENTE<br />

por Maurice F. Strong<br />

410-1476 West Broadway<br />

Vancouver, BC V6H 1H4, Canada<br />

Riproducimos a continuaci6n el prolqo escrito ror Maurice F. Strong<br />

p m et tibro de Pablo Bifani, Desmo'ilo y nedio mbiente*. Uaurice -<br />

F. Strong, de Canada, fue et Secretario General de la Conferencia de las<br />

Hacionee hidas sobre el rnedio ambiente (Estocolmo, 19721 y el primer<br />

Director Ejecutivo del Progrma de las Ba.ci.ones Unidas para el Medio<br />

ATlbie^te ( P M ) y es mienbro fundador ds IFCA.<br />

Es my oportuno que el doctor Bifani haya terminado este<br />

importante libro* en ei aiio del decimo Aniversario de la<br />

Conferencia de la Naciones Unidas sobre el Medio Anbiente<br />

Humano, que se llev6 a cabo er. Estocolmo en 1972. El prin-<br />

cipal tema de la Conferencia fue la necesidad de reconciliar<br />

la preocupaci6n por el rnedio ambiente con el imperative del<br />

desarrollo econ6mic0, particularmente en el Tercer Mundo.<br />

Pero una cosa es estar de acuerdo con esa tests a nivel<br />

conceptual y otra bastante distinta aplicarla a niveles<br />

prScticos, sobre 10s cuales son tomadas las decisiones que<br />

conciernen a1 desarrollo,<br />

En la d6cada que nos separa de la Conferencia de Estocolmo,<br />

ha lleqado a ser cada vez mSs evidente que 10s mejores me-<br />

dies efectivos, y frecuentemente 10s Cnicos, de hacer frente<br />

a 10s inipactos ambientales de grandes proyectos y proqramas<br />

para el desarrollo estZn en la primerisima fase del proceso<br />

ae planif icaci6n. Una consideraci5n plena y ob jetiva puede<br />

ser dada a las consideraciones amhientales s61o durante la<br />

fase de planificacitin como para asegurar que estgn completa-<br />

mente incorporadas dentro del anSlisis global costo-benefi-<br />

cio, sobre cuyas bases serSn tomadas las decisiones. Existen<br />

muchisimos ejemplos de impactos ambientales que s610 se con-<br />

sideran despues que el proyecto ha alcanzado la etapa en que<br />

hay tal grace de cornpromiso cue 10s cambios serlan dificiles<br />

o demasiado costosos de realizar.<br />

Las Gnicas alternativas en esta etapa son frecuentemente<br />

abortar el proyecto o continuar con 61, sabiendo que 6ste<br />

producirS serias consecuencias medioambientales que podrian<br />

hafcer side evitadas o mitiqadas, si hubiesen sido considera-<br />

das en una etapa anterio~. Estos dilemas estSn acompanados<br />

inevitablemente pot costos y conflictos sociaies, que pueden<br />

* Publicado por MOW Minister& de Gbras PubZ'iaas y Urbanismo, Madrid,<br />

Espa&, 193-1, ^p. 493.

Este libro va a1 ;:or4?5n de lsi relaci6n rie.i.arr'~llu-medio<br />

ambisnt.s. L,:]a chro que ios asunto; ambientalea no p'~f.Jer;<br />

ser considera'i-JS como meros hech;>s extemos y afect-223s pcr<br />

el proceso de ;i~--;drrc'U.o, sir-io ?ono hechos intcinst,, ...;v 1.3timamente<br />

,rslneion.-tJc~ :.ri a1 proceso mi.smo. EL :.oncebto mas<br />

precise de des~rrollo Jebe inclnir tcrl2s 10s aspec~os dc le<br />

vida hulr.ana y soi:ial, y no estar lj.~'.~tcido 3l ¡3trf?ch en-<br />

, .<br />

toque qua comp.ara el des-irrallo cor el craciniier.+~:, ec-;~::oiii~- -<br />

CO. Coma La Declaraci6n de Cocoyoc zstipulaba:<br />

EL este ^iiodo, prot,cger me jorar el 1ne~1.i J m.ni srici-- inipd:;'t.':vdo<br />

sobre l ~ s valores y kx-i ~1.enest.ii.r hu-~.ar:.u, deb-: se: victi..como<br />

la pri:nera i::ete de desair,~llo ra.;i:;r-.a1 y -1.2 con'.:, un<br />

r:-.ro f'ecko -.esun33n'?. L:;s dife.r.i?nt.?o si.-iterp.:i':; d.': v::Lc!re.;<br />

producirZin -31 ferenti"; '^ã^¥r.

a-i., y '-la pr-e.stai insuficiei-.tx atencifiri a la interacci6n de<br />

10s di.vi='~:~~s elemer~tos sectoriales qde caracterizan 10s sisternas<br />

L+LISJ.-efecto del mundo real.<br />

For 1.o cornfin, el analisis del costo-heneficio ha side llev-<br />

ado a cabo dentro du un ct.ntexto deinas-iadc restringido que<br />

frecuentemente omite , de torrid cor.iplc.ta, La consideration de<br />

los cosl-os y bereficios cue scn fundamentales en la determi-<br />

riacifir. 4e las verciaderas consecuencias de una decisi6n, en<br />

tgrminos ~5e ics 35,s amplios objetivos e intereses reales de<br />

la sociedad. Nueatrcs sistemas de tona de decisiones deben<br />

se'r red'Lser.ac3os para aseqt.rar que produzcar. las consecuen-<br />

cias quo de3eair.o~<br />

Tan-bi6n existen los problemas del conocimientc. La ecoloqia<br />

y las cie~cias ambientales son uisciplinas relativamente<br />

nuevas, y tcdavia no se han asimllado totalmente en 10s habitos<br />

y prsctxcas de Los ~~suarios de las disciplinas tradicionales.<br />

in cl us^ donde el conoc imiento estZ dispcnible, los<br />

m6todes de uso ;r aplicaci6n del mismo hacla la tcma de deciaioiies<br />

son cndavfa inadecuados, tienden a orientarse rn5s a<br />

.apiicac:i.c?.ea se-'.-toria'ie~ qua int-erd< sciplinarias.<br />

La e1c;buracifin 12e las nuevas herramentas y metodoloqlas<br />

requeridas para hacer fr6:nt-e rie forma efect.iva a la torna de<br />

decislones ~.ulttdiscLplinarias, requiere 1.2 capacidad de<br />

percibir las cormecuencias de cacia :.ins de Ins acciones invo-<br />

1ucraL.a~ en dl de.aarrolic de una riecisifin, y anticipar las<br />

rnei'lidds

las necesidades de la ~oblaci6n. Virtualmente, en todos 10s<br />

parses, la poblaci5n estS creciendo tanto en nihero como ex<br />

sus demadas de una vida mejor. La relacion entre ".as necesi-<br />

dades de la poblacion creciente y las presiones para el des-<br />

arrollo de 10s recursos naturales es uno de 13s principalas<br />

problemas que confrocta la actual comu~idad mufidial. Es un<br />

problema de dimensior~es globales, per0 al que debe nacer<br />

frente cada pals y cada region dentro del contexto de sus<br />

propias condicicn-ss particulares. Sin embargo, cualquiera<br />

que sean sstas condicicnes, deben inevitablemente afectar y<br />

ser afectadas por las decisiones tomadas en reiaci.6n con<br />

cuestiones partjc'l-iares del desanollo.<br />

El carScter sist6r'iico del rundo real en "1 cual deben ser<br />

tomadas las decisiones, no sol-o requiere que Las decisiones<br />

sobre el desarrollo individual sean tomadas sobre la bass<br />

del sistema total de causa y efecto.. sobre las cuales impac-<br />

tan, sino que cada decision se relacione c&n tc'das 12s otras<br />

decisiones que interactfian en la formacion y din2mica da<br />

nuestro future en su conjunto. Este es clararc.ente un reque-<br />

rimiento que no sera facii- de alcanzar. Sir. embargo, es ob-<br />

jetivamente necesario si han de estar asegurados la sequ-<br />

ridad y el biecestar de la familia huxana. La realidad as<br />

que vivimos dentro de un sistema global, donde las acciones<br />

tomadas en cualquier parte de 61, pueden afectar la salud y<br />

el destino de todo el sistema. En el m5s amplio sentido,<br />

estamos, por 10 tanto, obligados a idear un sistema de toma<br />

de decisiones acorde con esta realidad.<br />

El libro del doctor Bifani es urid notable contribution para<br />

encaminarnos en esta direction. Denuestra clararnente La ne-<br />

cesidad de integrar 10s aspectos ambientales er! 10s aspectos<br />

econ6micos y sociales de la toma de decisiones, como una<br />

parte integral del proceso de planificaci6n. Destaca una<br />

metodologla especlfica basada en an enfoque sist6mico del<br />

anSlisis, que incorpcia datos empiricos y experiencia con-<br />

creta, mostrando sobre una base objetiva las interrelaciones<br />

entre el sistema socioecon6mico y el sistema rnedioambiental,<br />

y dando expllcitamente plena consicleracion a cuestiones so-<br />

ciales y politicas. EstS basado er. el uso de solidos sis-<br />

temas t6oricos, justi ficados por datos hist6ricus y met.odo-<br />

loqia practica.<br />

~ s t e libro es optimists. Aunque plantea 10s problemas y escollos<br />

en Los modelos actuales de la planificacion del desarrollo<br />

y la toma de decisiones, demuestra tambign que pueden<br />

superarse con nuevos enfoques mSs globales y realistas a<br />

la vez. Deja clarc que el hombre moderno es capaz de asumir<br />

el control de su propic destino, que Los pasmosos podereri<br />

que la ciei:cici y la i_e~i;~tl~yld han puesto er, nuest.rasi manos<br />

pueden utiiizarse para lograr la clase de futuro a la que<br />

aspiramos. Con este libro, el doctor Bifani pone de manifiesto<br />

que es posible realizar esto, y ha estabiecido lineamientos<br />

claros para llevarlo a cabo. El autor ha contribuido<br />

notablemente a la realizacifin de los objetivos establecidos<br />

por la comunidac? mundial en Ia Conferencia de Estocolmo.

<strong>ifda</strong> <strong>dossier</strong> <strong>50</strong> . november/decembpr 1985 third world space<br />

THE WOMEN'S HilVF^ENT: A LATIN AXERlTAiY ?ERSPECFIVE<br />

by Adriana Santa Cruz<br />

Ferrpress-ILET<br />

Casilla 16637, Correo 9<br />

Santiago, Chile<br />

l.?E5 viz be remembered as the yea? of the Ingest ever meting of w^en<br />

from all uvrr the ylobe, partlu at the United Sations Corferenee but<br />

pirnzrily at the Women's Forum in ukick 14,003 1Jonen par*ticipated. A<br />

number of IF'% associates uere actively pr'ssert, and our readers ui11<br />

find herwafter three regional perceptions (Latin America, Africa an6<br />

Asia) of tke -present stage of the wmsn's ,mmerrent. It is our hope that<br />

shc.lt be +: a pos-i.ti.on to publish moz2s n":rerGz'is [information and.<br />

cfiatysis) on this ('pocl-maki~c; gathering.<br />

Our Latin America, so grand and full of contrasts, is hard<br />

to describe from a bird's-eye VT-PW or sum up with the stroke<br />

of a pen. The same can be said of the Women's Decade. These<br />

have been years, as WP say iieie, of "sweetness and lard",<br />

with much to celebrate and more than a little to lament.<br />

The fact that, in this part of the Third World, women are<br />

spared the barbarity of clitoridectomy, the practice of open<br />

poligamy and the obligation of veiling their faces, are ad-<br />

vances we d-' not owe to this Decade. Our "machisma" does not<br />

always reveal its evils so openly. But how dramatic it is<br />

that the real women of our continent are hidden behind the<br />

image of the Transnational Feminine Model - that wealthy,<br />

triumphant, North American or European woman removed from<br />

:he context. of her real world and in search of a man, "re-<br />

flected" and publicized by the mass media. It is tragic to<br />

see how the abuse, battering and rapes suffered by so many<br />

of the so-called weaker sex continue to be an open secret,<br />

recognized by women's organizations only. The same blind eye<br />

is fixed on the deaths of millions of women in abortions<br />

that poverty could not afford. What about the knowledge that<br />

unshared household chores - a responsibility for millions of<br />

poorly-paid working women - are not Divine Law? Or legisla-<br />

tion which assumes that the man is the head of the home<br />

when, in some countries, more than half of the households<br />

are headed by women? Or the regrettable absence of conscious<br />

women from the halls of power, an obstinate lack which con-<br />

tinues to deprive the world of humaneness and balance? And<br />

last, but not least, what about the fact that the terms fe-<br />

minism and feminist are still considered to be stigmas?<br />

The list is long, and it doesn't end here. Frightened and<br />

misinformed women help to perpetuate this state of affairs.<br />

As educators, they don't question traditional roles. As vot-

ers, they cast ballots for men without demanding commxtment<br />

to the women's cause. Women are largsly rCispons.,ble for the<br />

election of Alfonsin in Argentina, but never before have<br />

they been so under-represented in Parliament. In Ecuador,<br />

the number of women representatives in Congress has droppad.<br />

In April, the two feminist car.di:lates runrung Lor the Peru-<br />

vian Congress were riefiiated. And, in Chile, a re.'e::f S-. rvey<br />

reveals that women are a majority among those still support-<br />

ing the military regime,<br />

Add to this desolate panorama kY.a fact th2t the 2nd of the<br />

Decade finds us in the midst of a deep econcmic, social an..?<br />

political crisis. The region is burdened by foreign debt and<br />

the imperial policies of Ronald Reagan in Central America.<br />

It is the women of this continent who suffer the effects of<br />

the crisis most acutely, for the rope always breaks at its<br />

weakest point.<br />

Fortunately, these ten years have given us much to celebrate<br />

as well. The greatest achievements, it must be said, have<br />

not occured at the government level but in the "i;on--;overri-<br />

mental" world. Even the signing and ratification of tha<br />

United Nations Convention for the Non-Discrimination c Wo-<br />

men has been difficult to achieve, let alone put into prac-<br />

tice. But among the millennia1 prejudices and taboos, the<br />

empty promises of modernity and the obvious lack of resourc-<br />

es, a web is being woven in Latin America whose threads are<br />

clearly penetrating the fabric of society. This Dec,id.:- has<br />

witnessed the emergence not only of women's movemants but<br />

also of concepts destined to bring about unpredictable<br />

changes. What the Decade has really shown us is that this<br />

challenge is more than a ten or twenty year affair.<br />

In the shadow ~f the Left<br />

The process of organizing and consciousness-raising has qct<br />

been uniform throughout the region. The Central Ariencan<br />

nations are different from those countries wir'h have scrupulously<br />

preserved their democracies, while, in the Southern<br />

" -one, nations sank into the darkness of right-wing military<br />

dictatorships or are lust beginning to recover.<br />

It is also important to distinguish between won'en's an 1 fe-.<br />

minist movements, although they are closely linked. In Latin<br />

America, both have grown under the shadow of the Left, fruit'<br />

which they inherit their strength and weakness. The majority<br />

of organized women in this continent come fiom the poorest<br />

urban and peasant sectors, where organization is the result<br />

of the struggle to satisfy such basic needs as housing,<br />

health, food and jobs.<br />

It is astonishing that ev,en feminist movements led by middle-<br />

class intellectuals still focus their activity exclusively<br />

on lower-income women. Thus, they lack the strategies to<br />

convince their own class, so staunchly set in opposition to<br />

feminist ideals. Women's specific demands, tenaciously sub-

ordinate* to the class problem by the Left, have been the<br />

source of tension and recriminations.<br />

Even iri Cuba. however, the Federacicn d.? Mujeres has recenti.y<br />

beqiin to question the revolutionary justification behind<br />

the fact that. women run home to cook and clean while their<br />

c o m n a have ~ ~ ~ time to devote to union or party activities.<br />

The women of Hicaraqua, El Salvador and Grenada have lived<br />

. .<br />

at. war wi-cri :::;itii American imperialism, while the women of<br />

Chile, Paracuay and, until recently, Araeni-ina arid Uruguay,<br />

struqqle against nght-winq military rule and misery. As a<br />

result, even organized women often view with suspicion and<br />

sonetimes open rage the feminist call for autonomy from<br />

patriarchal power, a presence still stronqly felt in the<br />

parties of the Left.<br />

The divided Left, incapable of generating the confidence and<br />

consensus it needs to overcome its own popularity crisis, is<br />

dragging the women's movement along with it. For the first<br />

time in Latin America, two "admitted" feminists sought seats<br />

in the Peruvian Parliament, as candidates for the Izquierda<br />

Unida (United Left). Their defeat seems to indicate that<br />

neither the parties nor women in general appreciated the<br />

alliance.<br />

For the moment, the initiative towards autonomy and the in-<br />

sistence upon the specific nature of women's problems are<br />

charged with guilt. For a social movement so closely linked<br />

to political, social and economic realities, misery and the<br />

systematic abuse of human rights do matter, and a lot.<br />

perhaps it is this dilemma that puts Ilati.- America a t 2<br />

forefront of tmiorrow's challenge: the opportunity to con-<br />

front the inequalities of class and qender simultaneously.<br />

-p--<br />

The Catholic Church, a great promoter of grassroot organi-<br />

zations, has reacted with sensitivity and support to demands<br />

for the satisfaction of basic needs. But the church is also<br />

a powerful obstacle to the resolution of such dramatic prob-<br />

lems as abortion, contraception and divorce, issues hotly<br />

debated in Mexico and Brazil, and more discreetly discussed<br />

elsewhere.<br />

Feminine solidarity<br />

Latin Americans legitimately question the stated objective<br />

of the Women's Decade. The incorporation of women into de-<br />

velopment. "What kind of development?" they say, and "We<br />

women have always been an essential part of development,<br />

since the beginning of time." Yet today we are witnessing<br />

the tremendous growth of research to rescue women's history,<br />

to identify forms of gender discrimination, to expose fal-<br />

lacies and justifications and to break these patterns<br />

through research-action projects. Women's centers, legal aid<br />

offices, health projects and the like have made their ap-<br />

pearance in most of the countries in the region. Magazines,<br />

bulletins, radio and TV shows, regional information networks

(Unidad de Comunicacion Alternative de la Mujer, ISIS, La<br />

Tribunal, health, research (ALACEM) and even news services-<br />

(DIM and Fempress) have been launched (and sometimes dis-<br />

banded). Such efforts reinforce one another to overcome ato-<br />

mization and are living proof of the Latin Americanist voca-<br />

tion of the region's women's movement. None of these tasks<br />

are simple, and all require enormous involvement and compli-<br />

city in order to take advantage of chronically scarce re-<br />

sources and space.<br />

This period has also seen the proliferation of hundreds of<br />

meetings and seminars at local, national and regional level,<br />

particularly over the past five years. Specialization is now<br />

a necessity, as the wealth of accumulated knowledge no long-<br />

er fits within one office, much less a single mind. This has<br />

been made possible by the foreign funding generated during<br />

the Decade and by the pressure which supportive women in the<br />

industrialized nations exert on their own governments.<br />

The influence of feminism<br />

Despite the prejudices held against feminism, its influence<br />

is significant and there are reasons to believe that we are,<br />

indeed, at the doorstep of utopia. For instance:<br />

. The most lucid studies have been conducted by feminist<br />

women, or researchers often become "converts" along the way.<br />

At the Non-Governmental Regional Conference held last Novem-<br />

ber in Havana to evaluate the Decade, feminists conducted<br />

most of the workshops, winning recognition for their object-<br />

ive capabilities.<br />

. It is no longer sufficient just to question the discri-<br />

mination of women at the public level. The issue now is how<br />

to value and share domestic work and how to bring private<br />

matters into public debate. As the women of Chile demand in<br />

street demonstrations: "we want democracy In our country and<br />

in our homes. "<br />

. In "development projects", in community organizations<br />

promoted massively by the Catholic Church, in unions and in<br />

women's branches of politica.1 parties where women's issues<br />

have not been dealt with specifically, rebellion is now more<br />

than a murmer. For example, it is no longer common to hear<br />

that: "sexuality is a luxury, a concern only for those who<br />

have overcome hunger and poverty." A case in point is the<br />

women's program of the Vicarfa Norte, a church project in<br />

Santiago, Chile, coordinating more than 140 women's groups.<br />

After six years, and despite frequent failures of these<br />

groups to fulfil their specific goals, the organizations<br />

hold together. "Beyond the need for things we call basic,"<br />

says a program organizer, "it. seems there is a need for<br />

identity. "<br />

. After the electoral defeat in Argentina, women's groups<br />

formed La Multisectorial, a coalition to lobby specificallv

on behalf of women's issues. The group has already obtained<br />

legislation establishing Shared Patria Pctestad and is now<br />

threatening to cast blank votes if women are not better po-<br />

sitioned in upcoming legislative elections.<br />

. In Uruguay, attempts were made to isolate women's orga-<br />

nizations from La ConcertaciGn Democrstica, a move which<br />

kindled solidarity among them and led to the creation of the<br />

Plenario de Mujeres. Here, party differences have been set<br />

aside and combined pressure placed on behalf of a program<br />

demanding changes in practically every area imaginable.<br />

GRECMU, a study center with a clearly feminist orientation,<br />

is a leading consultant to this task.<br />