Rodziny - Polish Genealogical Society of America

Rodziny - Polish Genealogical Society of America

Rodziny - Polish Genealogical Society of America

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

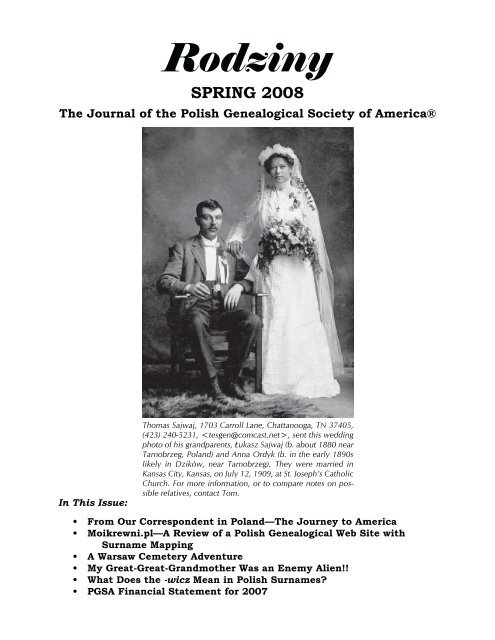

<strong>Rodziny</strong>SPRING 2008The Journal <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>®In This Issue:Thomas Sajwaj, 1703 Carroll Lane, Chattanooga, TN 37405,(423) 240-5231, , sent this weddingphoto <strong>of</strong> his grandparents, Łukasz Sajwaj (b. about 1880 nearTarnobrzeg, Poland) and Anna Ordyk (b. in the early 1890slikely in Dzików, near Tarnobrzeg). They were married inKansas City, Kansas, on July 12, 1909, at St. Joseph’s CatholicChurch. For more information, or to compare notes on possiblerelatives, contact Tom.• From Our Correspondent in Poland—The Journey to <strong>America</strong>• Moikrewni.pl—A Review <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> Web Site withSurname Mapping• A Warsaw Cemetery Adventure• My Great-Great-Grandmother Was an Enemy Alien!!• What Does the -wicz Mean in <strong>Polish</strong> Surnames?• PGSA Financial Statement for 2007

Ta b l e o f Co n t e n t sNews and Notes from the President.........................1Letters to the Editor...................................................1From Our Correspondent in Poland—The Journeyto <strong>America</strong>, Iwona Dakiniewicz...........................3Moikrewni.pl—A Review <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong>Web Site with Surname Mapping, Robert P.Sliwinski..............................................................6A Warsaw Cemetery Adventure, Phyllis M.Sternemann........................................................9Ask the Retoucher, Eric Basir.................................14Attention All PGSA Members..................................15Follow-Up to Iwona’s Galician Railroad Article,Margaret Wolan Sullivan...............................16My Great-Great-Grandmother Was an EnemyAlien, Kenneth P. Nowakowski......................17What Does the -wicz Mean in <strong>Polish</strong> Surnames?,Keith Kaszubik...............................................22From the Słownik Geograficzny: Tarnowiec............24From the Library: Book Review, Virginia Witucke...25PGSA Financial Statement for 2007.......................26Articles <strong>of</strong> Interest...................................................27Index to Surnames Mentioned in This Issue...........28Po l i s h Ge n e a l o g i c a l So c i e t y o f Am e r i c a ®984 No r t h Mi l w a u k e e Av e n u e • Ch i c a g o, IL • USA • 60622— An Illinois Not For Pr<strong>of</strong>it Corporation —OfficersCommitteesEdmund Iwanski........................................PresidentLinda Ulanski......................................Vice PresidentJoy Mortell............................................... TreasurerThomas Zarecki.........................................SecretaryEileen CarterIrene-Aimee DepkeSonja Hoeke-NishimotoDirectorsRichard LachRichard StanowskiIrene-Aimee Depke.............................. PublicityLarry Grygienc.........................................MediaChristine Bucko................................... Web site[Open]...............................................PublicationsRich and Barb Szparkowski........... MembershipLinda Ulanski................................... Conference[Open].............................................Library ChairPGSA’s e-mail address is pgsamerica@aol.com. Its Website is at http://www.pgsa.org.Statement <strong>of</strong> MissionThe <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>® (PGSA) exists as a national nonpr<strong>of</strong>it educational organization to collect,disseminate, and preserve information on <strong>Polish</strong> and <strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>n family history and to help its members use thatinformation in their own research.PGSA Publications PhilosophyThe PGSA will consider for publication articles, books, edited documents, bibliographies, anthologies, reviews, and otherwritings pertaining to all aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>Polish</strong> genealogical research from all parts <strong>of</strong> the world. The PGSA invites the submission <strong>of</strong>interesting and educational stories on genealogical research, including those acknowledging the efforts <strong>of</strong> helpful researchers,librarians, state and religious archives, or other persons and organizations. The PGSA also welcomes contributions thatexamine the historical and cultural heritage <strong>of</strong> our ancestors and families.MembershipEffective January 1, 2008, membership rates were increased by $5, and the 3-year membership option was discontinued.Membership rates have been unchanged for several years, and during that time the costs <strong>of</strong> printing and postage have goneup. Of course, all current multiple-year memberships will be honored until their expiration date. Effective January 1, 2008,the new rates are:1 year 2 years 1 year 2 yearsBulk-rate mailing $25 $40 Canada $30 $50First-class mailing $30 $50 International $40 $70The mailing label states the expiration date <strong>of</strong> your current membership. If you have any questions, please e-mail themto . Renewal applications are available at www.pgsa.org. Please send change <strong>of</strong> address or duesto the Membership Chairmen, Rich and Barb Szparkowski, 1603 E. Linden Ln., Mt. Prospect IL 60056-1529. Makechecks or money orders payable to “PGS <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>,” in U.S. funds. Thank you!MeetingsRegular meetings <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Society</strong> are held on the second Sunday <strong>of</strong> February, August, and November, and the third Sunday<strong>of</strong> May, unless otherwise ordered by the Board <strong>of</strong> Directors. They are usually held at the <strong>Polish</strong> Roman Catholic Union <strong>of</strong><strong>America</strong> facilities, 984 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago. An annual <strong>Society</strong> Conference with several speakers is held in the fallat a location in the Chicagoland area. A United <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> Societies Conference is held in May biennially in SaltLake City, Utah.

From Our Correspondent in PolandThe Journey to <strong>America</strong>Iwona Dakiniewicz, Łódź, Poland;e-mail: genealogy@ pro.onet.pl[with translation assistance from William F. H<strong>of</strong>fman]They all departed in fear <strong>of</strong> the Unknown:fear <strong>of</strong> losing their way, <strong>of</strong> beingstopped at the border, <strong>of</strong> arrest, <strong>of</strong> thehordes <strong>of</strong> swindlers, <strong>of</strong> the voyage by ship,and <strong>of</strong> the fate that awaited them on a newcontinent. Nonetheless, their great hope fora better, more decent life was stronger thanall their fears and anxieties. They set outwith no possessions other than their healthand their family.During the years 1840-1920, more thanfour million citizens departed from Poland.There was an all-encompassing determination:the emigrants were fleeing poverty intheir native land, which furthermore was aland enslaved by foreign partitioners. Theyfelt they were slaves in their own land. Theylived in wretched conditions, <strong>of</strong>ten morethan a dozen to a single hut, abused bytheir employers, with little chance <strong>of</strong> betteringtheir lot. But there were other motivationsas well: escaping military service,curiosity about the world, or, finally, theordinary desire for personal freedom.The motivations <strong>of</strong> emigrants can alsobe differentiated on a geopolitical map. Ineach <strong>of</strong> the individual partitions, Prussian,Russian, and Galician, a different kind<strong>of</strong> repression prevailed against the nativeinhabitants.In Prussia, they were tormented by thepolicy <strong>of</strong> Germanization. In fact, in that partition,things went so far as a school revolution.The police jailed thousands <strong>of</strong> rebelliousPoles. But the more people they jailed,the higher the flame <strong>of</strong> vengeance rose. Theweary ones who dreamed <strong>of</strong> a normal lifebecame emigrants.Also worth mentioning are two otherPrussian issues. The earliest wave <strong>of</strong> emigrationfrom Prussian Poland was the result<strong>of</strong> natural disasters and years <strong>of</strong> famineduring the period 1844-1847. The secondfactor was the result <strong>of</strong> an 1848 Prussiandecree that ordered men ages 17-25 topresent certificates to military authoritiesattesting that they would not dodge militaryservice. Because <strong>of</strong> this, many young menleft illegally.Those who left overpopulated Galiciawere fleeing high taxes and starvationwages. Some 50 thousand people died eachyear from starvation. Harsh reality prevailed:the averaged Galician farm was nolarger than five Austrian mórgs, and workerswere paid pitiful wages. If you had ahorse, you were a rich man.In the Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Poland, on the otherhand, unemployment was rampant. Peoplefrom the Russian partition ran <strong>of</strong>f toPrussia to find seasonal labor there. Oftenthey took the place <strong>of</strong> Prussian emigrantswho had already settled in <strong>America</strong>. EmpressCatherine poured oil on the fire whenshe issued a ukase liquidating the UniateChurch in 1873. Religious repression becamea rape for these communities, and atthe same time an essential cause <strong>of</strong> emigration.Desperate Greek Catholic believershad two choices: to conduct their churchservices in the woods at night, or to travela long way to the nearest church. Many <strong>of</strong>them traveled on foot to Kraków.One can give many numbers and statisticsregarding the scope <strong>of</strong> emigration, butwhat is most interesting here is the humanfactor—how each <strong>of</strong> these individuals experiencedthe parting and the voyage acrossthe ocean.Emigrants were more or less informedabout the obstacles and difficulties <strong>of</strong> thetrip to <strong>America</strong>. News came to them in letters.The first obstacle to overcome was collectingthe necessary sum <strong>of</strong> money: for thetrip to the railroad station, then for traintickets, ship tickets, other expenses on theroad, and a minimum to help them get <strong>of</strong>fto a start in their new country. The totalcost <strong>of</strong> the trip could range from 150 to over200 marks or rubles, depending on wherethe trip began.<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 3

Fro m Ou r Co r r e s p o n d e n t in Po l a n d : Th e Jo u r n e y to Am e r i c aHow difficult it was to save thenecessary funds is illustrated by thesituation <strong>of</strong> a typical married couple livingin a Prussian village with several childrenin the 1840s. Both husband and wife,employed in physical labor at the nearbymanorial farmstead, could not hope toattain a combined income <strong>of</strong> more than 40dollars annually (the equivalent <strong>of</strong> about120 marks later). At the most, they couldsave perhaps 10 dollars a year.At first, several families would contributeto buy a single ticket to <strong>America</strong>, inthe hope that the one chosen to go wouldquickly find work and repay the loan, thusproviding financial assistance to those departingsubsequently.As <strong>of</strong> the years 1888-1889, a ticket fromBremen to New York cost 150-200 rubles,or 120-200 Austrian crowns, and aboutthe same amount in German marks. A tripfrom Poznań to Chicago cost 30 dollars in<strong>America</strong>n money, by the rate <strong>of</strong> exchange atthe time. The firm Red Star <strong>of</strong>fered a competitiveprice: 21 dollars for a trip from thePrussian partition to many <strong>America</strong>n ports.The <strong>Polish</strong> emigrant <strong>of</strong>ten had a tragicview <strong>of</strong> the price <strong>of</strong> ship tickets, for hewas sure that they wanted to cheat him.Although the prices were fixed, he felt hewould not waste the money and would bevery cautious and frugal with it.The first to go were strong, healthy men,who went as a sort <strong>of</strong> advance guard, to getfamiliar with the new land and estimate thechances <strong>of</strong> bringing the family on over assoon as possible. Those who were particularlyresolute and determined sold <strong>of</strong>f theirlands, houses, or share <strong>of</strong> inheritance fromtheir parents. I noted interesting cases inwhich the same land was sold to two differentpurchasers. By the time the truth cameout, the cunning farmer was already beyondthe reach <strong>of</strong> the local jurisdiction.The departure from home was a verysolemn day for the family, and sometimesan event for the whole neighborhood. Bestwishes were accompanied by tears <strong>of</strong> joymixed with fear. Usually the wives, children,and grandparents remained on thefarm. Over the course <strong>of</strong> the next year, thewhole family would follow in the steps <strong>of</strong>their fathers, brothers, or cousins. Thosewho remained in Poland were usually theold folks, or those who had been assignedthe role <strong>of</strong> guardians <strong>of</strong> the family nest.Emigrants usually got ready for the trip4 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008very carefully. They planned their departureto fit the work schedule on the farm and inthe field. They worked out plans beforehandwith their relatives or neighbors for a triptogether. They chose those who were hardworking,healthy, and upright. For thetrip they collected spare underwear, warmclothes, long boots, a blanket, tobacco,liquor for bribes, pierzyny [quilts, typically<strong>of</strong> goose down], photos <strong>of</strong> family and patronsaints, simple work tools, seeds, pots, castironpans, everything needed for pickling,and smoked or pickled food products. Themore informed they were regarding materialneeds in the new land, the more things theyassembled. Instructions came in lettersfrom <strong>America</strong>. Among other things, theywere advised to bring woolen belts to wearon the lower abdomen during the voyage, sothat in case <strong>of</strong> dysentery (bloody diarrhea)they could maintain a consistently warmtemperature in the belly area, whichalleviated the unpleasant effects <strong>of</strong> thisillness.Things were packed in wooden trunkspadlocked or nailed shut. These trunks alsoserved as stools for seating on the ship.Later on, however, the rules didn’t allowfor the use <strong>of</strong> padlocks or nails, because <strong>of</strong>customs controls.The Prussian border was the nextobstacle on the way, and not always inregard to formal considerations. Along thewhole eastern border <strong>of</strong> Prussia, there werehordes <strong>of</strong> swindlers <strong>of</strong> every kind: fakeguides, agents <strong>of</strong>fering phony ship ticketsor money exchange “at a bargain rate,” conartists collecting payment for half-free lodgingsfor the night, the usual thieves, andeven bandits. In general, the black marketand corruption flourished in the areas nearthe border. Almost everyone took bribes,from the wójt who issued departure certificatesto the soldier who guarded the border.Most <strong>of</strong>ten the bribes were in money, butnobody turned down vodka or tobacco.The paths <strong>of</strong> emigrants from Galicia andRussia came together in Prussian borderpoints in Mysłowice, Oświęcim, OstrówWielkopolski, Iłów, Prostki. The trip acrossGermany lasted two or three days.The railroad trip took them first toBerlin, where they had to transfer to anothertrain. The first contact with a foreigncountry was worrisome; the emigrants’ lack<strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> a foreign language causedthem stress. But they had to exchange

Fro m Ou r Co r r e s p o n d e n t in Po l a n d : Th e Jo u r n e y to Am e r i c amoney, buy the next ticket, and find a placeto stay for the night. Still, the hardest timeslay before them.The seaports during the times <strong>of</strong> peakemigration were swarming with thousands<strong>of</strong> emigrants stuck at the docks for two oreven three weeks. In Bremen and Hamburg,ships sailed twice a week, on Wednesdayand Saturday. The emigrants were forced towait for the ship on the spot. They crowdedrailway sidings, barracks, eating establishments,or churches; or they just wanderedaround the town, worried about their fate,lost in a foreign place, and left to their ownresources. Provisions cost 2½ marks a day,payment for a bed was 1 mark. When therewere no beds to be had, people slept underthe open sky.The ports full <strong>of</strong> foreigners were alsoheaven on earth for crooks, who tookadvantage <strong>of</strong> the naïve emigrants at everyopportunity.Reporters also came to the ports andpublished their stories in national andregional newspapers. In one <strong>of</strong> these articles,the author wrote: “All remember theirhomeland with tears in their eyes, in view<strong>of</strong> the fact that they were leaving, not bliss,but poverty…” (Kurier Polski, 1890, no.168).The voyage itself filled the emigrantswith terror but also attracted them withits exoticism. The last stage <strong>of</strong> the trip wasthe most exciting and most terrifying at thesame time. Fear <strong>of</strong> the Great Water musthave been a significant psychic barrier.None <strong>of</strong> the emigrants had ever traveledacross the ocean by ship before. The mostsevere voyages were experienced by the earlyemigrants, those who traveled on sailingships during the 1870s. The length <strong>of</strong> thesea voyage made the situation even worse;the first sailing ships took as long as 15weeks. They carried 200-500 passengers.The passenger sailing ships were unstable,and had primitive decks and cabins devoid<strong>of</strong> all comforts. There were deaths, drownings,and even suicides on almost everyvoyage.In the 1880s, a new era began—that<strong>of</strong> steamships. The number <strong>of</strong> passengersrose to as many as 2,000, and the length<strong>of</strong> the trip was shortened to 9-11 days. Thelargest ships, for instance, the Imperator or<strong>America</strong>, had a displacement <strong>of</strong> 50 thousandtons. Shipowners were compelled tobuild their ships according to the requirements<strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>n immigration <strong>of</strong>ficials.Among other things, they had to guaranteea minimum amount <strong>of</strong> space per passenger,appropriate sanitary conditions, andthree meals a day. These requirements werestrengthened in 1883; there had to be adoctor on every ship (in view <strong>of</strong> the moreand more frequent deaths).The German ships had the worst reputation,as well as the English. Of the ports,the one in Liverpool supposedly had theworst reputation.Poles, who were the poorest, traveled onthe cheaper German ships, on which theybought the cheapest spots, on the tweendecks.Many <strong>of</strong> them had particularly badexperiences during their voyages, and thestatutory social requirements repeatedlydeviated from the norm.Henryk Sienkiewicz, the <strong>Polish</strong> NobelPrize winner, described his impressions <strong>of</strong> avoyage thus:In general this is a large, dark room,where the light <strong>of</strong> day penetrates, notthrough glass-covered openings in thedeck, but through the usual small windowsin the sides <strong>of</strong> the ship. There areno cabins; beds are pushed all the wayto the wall, and the corner designatedfor women is set <strong>of</strong>f only by a separaterail. In stormy seas, the waves strike thewindows with a boom, filling the hallwith a gloomy, greenish light. The smell<strong>of</strong> cooking and <strong>of</strong> people combines withthe sharp odor <strong>of</strong> the sea, tar, and thewet ship ropes. All in all, it is stifling,humid, and dark there … It is in roomssuch as these that the emigrants travel.If you were to ask them from where,the answer would be “from under thePrussians,” “from under the Austrians,”“from under the Muscovites.” Despair,fear, and longing for their homeland aretheir lot.The end <strong>of</strong> the voyage did not mean theend <strong>of</strong> worries and problems; adapting tolife on <strong>America</strong>n soil was not the easiestthing to do. But horizons <strong>of</strong> a better futureseemed more and more close and real, andthe painful separation from their nativeland found an outlet in maintaining contactsby letters with their relatives in theold country and preserving their nationaltraditions on <strong>America</strong>n soil—as attested bythe number <strong>of</strong> <strong>Polish</strong> confraternities, clubs,and organizations that remain active to thisday in almost all the states <strong>of</strong> the U.S.<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 5

Moikrewni.pl—A Review <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> Web Sitewith Surname MappingRobert P. Sliwinski, M.S., e-mail <strong>Genealogical</strong> Web sites designed forPoles are becoming fashionable thesedays, because <strong>of</strong> an emerging interestin family history in Poland. One recentlydeveloped site catering to <strong>Polish</strong>citizens and allowing them to createfamily trees online is www.moikrewni.pl (Figure 1). This site, written in <strong>Polish</strong>,has a unique feature that may alsobenefit <strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>n genealogists:its surname mapping.The very existence <strong>of</strong> this site is aninteresting development because, forthe longest time, <strong>Polish</strong> citizens werevery private and did not like providingany personal information online. Sitesthat do give such information are protected,and you need to register to buildyour tree. There are, however, typicallysome features that are available to allwithout registering.In <strong>Polish</strong>, moi krewni (pronounced mo´yeekrev´-nee) means “my relatives.” Thesite’s title, therefore, uses appropriate <strong>Polish</strong>words to describe its theme.Worth noting, however, is the fact thatthis site is just one <strong>of</strong> a family <strong>of</strong> genealogicalWeb sites created by OSN Online SocialNetworking GmbH, based in Hamburg, Germany.Similar sites were designed for otherlanguages, including English, German,Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and BrazilianPortuguese. The English version, http://www.itsourtree.com/, is very similar to the otherWeb sites, but there are slight differencesbetween the various language versions.Moikrewni uses the basic “let’s build afamily tree” idea as its starting point. Additionally,it provides a forum, contact information,and a section regarding the company’spolicies. As I said, though, the featuremost valuable for <strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>ns is the“Mapa nazwisk” or “surname map” at http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/. Mapping <strong>of</strong> surnamesin current-day Poland can potentially be auseful tool to locate lost relatives in the oldcountry. It is especially useful for uncommonsurnames.Remember, however, that the site isgeared toward the <strong>Polish</strong> speaker, and aname you type into the “Mapa nazwisk” boxcould be only partially correct. The <strong>Polish</strong>6 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008Figure 1. Home page <strong>of</strong> www.moikrewni.pl (all screen capturesused with permission <strong>of</strong> the Moikrewni webmaster).diacritical marks are very important on thissite, and the database may contain numerous,slightly different variants <strong>of</strong> surnameswith diacritical marks. For instance, if youtype in Sliwinski in English and click on thebutton that says “Szukaj” (Search), you willget a map for Sliwinskis in Poland; but thismap will be misleading and incomplete.In <strong>Polish</strong> the standard spelling <strong>of</strong> thisname is Śliwiński, with acute accents overthe s and n. Variant spellings <strong>of</strong> the nameinclude Śliwinski and Sliwiński. To illustrate,a search for Sliwinski tells you that as<strong>of</strong> 2002 there were nine <strong>Polish</strong> citizens whowere listed under that name in the database<strong>of</strong> PESEL (a <strong>Polish</strong> government agency)from which these figures were compiled.There were 31 entries for Śliwinski and 119for Sliwiński. A search for Śliwiński, on theother hand, shows you there were 8,955Poles who spelled it that way. The diacriticalmarks make a difference!What’s more, Poles use feminine forms<strong>of</strong> many surnames, including those typicallyending in -ski, -cki, -zki, and -ny. Thestandard feminine form is Śliwińska, and9,570 <strong>Polish</strong> citizens went by that formas <strong>of</strong> 2002—not something you’d want tooverlook. The variants Sliwinska, Śliwinska,and Sliwińska, though not technically correctby <strong>Polish</strong> spelling rules, should not be

Mo i k r e w n i.p l—A Re v i e w o f a Po l i s h Ge n e a l o g i c a l We b Si t e w i t h Su r n a m e Ma p p i n gFigure 2. “Mapa nazwisk” page with <strong>Polish</strong> alphabet.Figure 3. Searching for surnames.Figure 4. Map <strong>of</strong> the surname Śliwiński showing itswide distribution in Poland.ignored, either. It just might be that yourrelatives, for some reason, are among thoselisted under one <strong>of</strong> those variants.So to achieve a full understanding <strong>of</strong>a specific surname in Poland, you reallyneed to review all maps associated with allvariants <strong>of</strong> that surname. There are alsohyphenated surname combinations to bereckoned with; a study <strong>of</strong> Śliwiński, for instance,should also include Sliwinski-König.Although the diacritical marks presenta challenge, there is a convenient alphabeticaid located at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the “Mapanazwisk” page (Figure 2). All possible firstletters <strong>of</strong> surnames are represented, andclicking on any letter lets you start searchingfor names beginning with that letter. Itsounds straightforward, but it can take alittle longer to find your particular surnamewhen searching a list from one spelling toanother, and yours might be in between(Figure 3). Plan on searching several timesat different locations. You may need to pagepatiently through successive lists, narrowingthe possibilities down as you go, untilyou get the exact form you want.If the name you want doesn’t includeany diacritical marks, you can go straightto the page with your name by inputtingthe URL http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/XXX.html, substituting your name (no capitalletters) for the XXX. Thus http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/kowalski.html takes youstraight to the map for Kowalski, and http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/kowalska.html tothe map for Kowalska. This does not work,however, if names include diacritical marks.Thus http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/śliwiński.html will not work. Those <strong>Polish</strong>characters must be coded a specific way:http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/%25C5%259Bliwi%25C5%2584ski.html.The name Śliwiński is very widely distributed,and high concentrations are associatedwith big cities (Figure 4). Althoughthis is interesting, it does not point to a<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 7

Mo i k r e w n i.p l—A Re v i e w o f a Po l i s h Ge n e a l o g i c a l We b Si t e w i t h Su r n a m e Ma p p i n gspecific region in Poland and thus providesno starting point for researching thesurname. I’ve established that there are anumber <strong>of</strong> unrelated families who bear thisname. Therefore, old-fashioned documentsearches <strong>of</strong>fer a better chance <strong>of</strong> finding anancestral village for my family.Some surnames, such as Czopor (frommy mother’s side), have no separate feminineform and no diacritical marks, andtherefore there is only one map for that surname(Figure 5). Since Czopor is an uncommonname, this map has proven to be veryuseful. This surname shows high concentrationsin southeastern Poland.The data from the “Mapa nazwisk”search engine is comparable to the datafrom the searchable database at http://www.herby.com.pl/indexslo.html, which some call the“Rymut site,” after Kazimierz Rymut, the<strong>Polish</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essor who first compiled andpublished the data. Both sets <strong>of</strong> figurescame from the <strong>Polish</strong> government agencycalled PESEL, and both show the frequencyand distribution <strong>of</strong> surnames borne by<strong>Polish</strong> citizens—the Rymut site with datafrom 1990, Moikrewni with data from 2002.For some time it has been possible to createsurname maps by taking data from theRymut site and plugging it into the appletat http://www.genpol.com/Mapa+main.html. Butthat mapping program is not as sharp andeasy to use as Moikrewni’s.It’s interesting that Moikrewni shows1,710 more Śliwińskis than the Rymut sitedoes. [Editor—Rymut said the 1990 datalacked figures for about 7% <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Polish</strong>population, so the more accurate 2002 datawill <strong>of</strong>ten show larger numbers.] The Rymutsite combines the figures for the masculineand feminine forms, whereas Moikrewnigives separate maps and pages for eachform, and the total is up to you to calculate.The Rymut site breaks data down by the49 provinces <strong>of</strong> 1990, whereas Moikrewni’snumbers are broken down by current countiesor powiaty, not the 16 current provinces.The greater detail <strong>of</strong> Moikrewni’s data,and the ability to place your mouse over alocation on the map and see a county orcity name pop up, are particularly valuableto anyone not too familiar with Poland.Genealogists looking for all variantsand all data during searches may wish toconsult Rymut’s Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Surnamesin Current Use in Poland at the Beginning<strong>of</strong> the 21st Century, a CD published in8 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008Figure 5. Map <strong>of</strong> Czopor surname showing its comparativelylimited distribution in Poland.2002 by the <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>America</strong> (formerly sold by the <strong>Society</strong>, butnow out <strong>of</strong> print). That CD gives completebreakdowns <strong>of</strong> PESEL’s 2002 data for everycounty in which a surname appears, whereasMoikrewni lists data only for the 10counties in which a name is most common.Moikrewni’s maps, however, illustrate datafor all counties, not just the “top 10.”Moikrewni also allows you to incorporatethe surname maps it generates intoyour blog or family Web site. Naturally,the map includes the Moikrewni logo as areminder <strong>of</strong> where it came from.The forum portion <strong>of</strong> the Web site ishelpful for those with very good <strong>Polish</strong>writing skills. Fortunately, as mentionedearlier, there is an English-language version<strong>of</strong> the Web site, http:// www.itsourtree.com,and it provides contact information that willrespond to questions in English. The folksthere were very helpful with my inquiries.The English site does not have a surnamemapping feature, but you can access theMoikrewni site by clicking on the <strong>Polish</strong> flagnear the top right <strong>of</strong> the home page.<strong>Polish</strong>-language family tree Web sitesare aimed at the growing number <strong>of</strong> Polesinterested in genealogy. These sites attractnew clients by <strong>of</strong>fering different free amenitiesthat make the experience potentiallymore fruitful. With a little bit <strong>of</strong> assistance,<strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>ns can also use these freeamenities to benefit their research.

A Warsaw Cemetery AdventurePhyllis M. Sternemann, 74 Shore Rd., Manhasset NY 11030 By a stroke <strong>of</strong> good luck and after hours<strong>of</strong> planning, I was able to arrange child carefor my son and daughter in order to takea brief trip to Warsaw in January <strong>of</strong> 1998.My father’s 76-year-old cousin Łucja wasexcited at the prospect <strong>of</strong> seeing me again,since my previous visit <strong>of</strong> just 20 yearsprior. Aside from a quick catch-up withŁucja, my other goal was a cemetery visit tophotograph graves <strong>of</strong> my ancestors.After dropping <strong>of</strong>f my bag at the hotel,I skipped a chance to rest so I could getas much accomplished as possible in onlythree days. I met my prearranged translatorin the lobby, and <strong>of</strong>f we went by cab with abouquet for Łucja. The wonderful visit includednibbling cookies with tea, a review <strong>of</strong>her old photograph albums, and enthusiasticexchanges about the “olden days.” ThenI wrote down the name <strong>of</strong> the cemetery(Powązki) where her husband, Jerzy, wasburied and, way across the Wisła River, thecemetery where her parents lay (Bródno).Because <strong>of</strong> poor health, Łucja had not beenable to visit any graves for several years—not even for the special commemoration <strong>of</strong>All Saints’ Day, when pilgrimages acrossPoland by family members lead to gravesidereunions and cause horrendous traffic congestion.I thought it would be a nice gestureto photograph Jerzy’s grave and send acopy to her.Leaving her apartment while chatteringwith the translator about various waysto seek out dusty old records at the localarchival <strong>of</strong>fices, I realized I had forgotten toask Łucja for the burial plot locations.Early the next day, armed with my busmap, city map, Berlitz <strong>Polish</strong> phrase book,itchy wool sweater, down coat, ugly hat,and clunky snow boots, I stuffed my camera,wallet, passport, notepad, pen, waterbottle, and seven granola bars into mybackpack. Along with the names <strong>of</strong> thesetwo cemeteries and emergency provisions, Ifelt prepared to find the final resting places<strong>of</strong> my ancestors. I had no idea what was instore for me.Sure, the first cemetery, near the middle<strong>of</strong> the city, was easy to find, since thebus quickly stopped right at the main gate.Walking past the snow-covered graves <strong>of</strong>Above: A photo <strong>of</strong> Łucja Półtorak, 1938. Below:Her mother, Gizela Rychlewska Półtorak.<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 9

famous artists and writers, I sought thecaretaker’s <strong>of</strong>fice. Along the quiet pathbetween the rows <strong>of</strong> elaborate verticalmonuments, my muffled footsteps allowedthe crispness <strong>of</strong> the chickadee’s“bee-bee-bee” to sound out.The birds flitted from pine branchto tombstone and back again, escortingme, a lone visitor on a weekdaymorning, through this still place. Onelanded atop a tall stone, and I thoughtto photograph it, a small form <strong>of</strong> life inthis silent gray stone yard. But the birdwould not stay still long enough for meto dig through my pack and adjust thecamera. I walked on.Scanning each marker in the nextrow for names carved into the granite,I stopped abruptly at letteringwhich, surprisingly, spelled out JerzyKędzierski. How startling to see thevery name I was looking for, right thereafter the chickadee’s antics. Now, was itthe correct Jerzy Kędzierski? After all, thatsurname is extremely common. A quickreview <strong>of</strong> the dates, since the other <strong>Polish</strong>words were too hard to decipher, showedthat I had indeed found the grave <strong>of</strong> Łucja’shusband. The stone letters had been filledin by shaky hand with black paint, perhapsto aid the visually impaired. I adjusted thecamera and took a few shots from differentangles and a close-up.After repacking my bag and putting mygloves back on, I bid farewell to this manwhom I had only met once, whose storieswere kept secret since World War II. Perhapsto be contemplated later, since I hadyet another cemetery to travel to. The daysare shorter in winter.Three buses and two hours later, I wasover the river and past the zoo. The mapshowed that this bus should turn left soon,unless it’s the wrong bus. After the auto repairshops and stone quarry, my stop wouldbe just ahead, where clusters <strong>of</strong> fat candlesand plastic flowers were sold outside thegate <strong>of</strong> Bródno Cemetery. People were eagerto earn even a few złoty from sales such asthis. Yet they would only brave the cold ifthe sun was shining.The cemetery <strong>of</strong>fice staff attempted tohelp, but the language barrier was too high.My poor pronunciation <strong>of</strong> the surname wasridiculed as one worker mimicked to anothermy exaggerated vowels in the namePółtorak. Without the exact year <strong>of</strong> death,A Wa r s a w Ce m e t e r y Ad v e n t u r e10 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008Above: A photo <strong>of</strong> Bródno Cemetery on All Saints’ Day. Theoriginal is available at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Br%C3%B3dno_Cemetery?uselang=pl.they were unable to look up the grave’slocation on their computer. I did not wantthis long trip to be wasted; after all, whoknew when I might be able to return?So I decided to call Łucja. By myself,using my trusty Berlitz book. But where t<strong>of</strong>ind a phone? And how to obtain the coinsor token needed? At least I had her numberand some paper złoty with me. It was wortha try. The <strong>of</strong>fice worker politely waited asI mangled the <strong>Polish</strong> for, “Where is a payphone?” She used the ever popular internationalgestures to accompany her words,letting me know that a post <strong>of</strong>fice was downthe block, with a phone inside.Off I went, Berlitz book in hand, pastthe candle sellers, briskly now, as I wouldnot wish to remain in this neighborhoodafter dusk. In line at the post <strong>of</strong>fice, eyeingthe gruff unshaven man behind the counter,I waited uncertainly. My goal was toconvey a need not for stamps, but for theuse <strong>of</strong> a pay phone. Only for a local call—or does one have to dial a certain prefix? Asmile came to me as I realized the people inline behind me were in for quite an event.Here’s a woman who can’t speak <strong>Polish</strong>,trying to buy a phone token, taking toolong to make her request, and even if she issuccessful in procuring the desired phonetoken, the biggest question becomes: Whoon earth would she be trying to call sinceshe doesn’t speak <strong>Polish</strong>?So, I was next, and I used every politephrase I could. The sweat trickled along my

A Wa r s a w Ce m e t e r y Ad v e n t u r ebrow as my wool had done too good a jobwhile I was walking briskly to the overheatedbuilding. The postal man responded byholding up a plastic card, with a picture <strong>of</strong>a phone on it. I was so happy. Then, beforehanding it to me, he produced a hugesentence that I could not understand forthe life <strong>of</strong> me. It had nothing to do with allthe words swirling about in my head whichI had looked up while waiting—words suchas “phone,” “cost,” “ local call,” and the like.I was forced to produce the only fluent sentencein my repertoire: “I’m sorry, I do notunderstand.” At that moment, his gruffnessfaded while he snapped <strong>of</strong>f the perforatedcorner <strong>of</strong> the card to activate it for me.“Thank you,” I replied, in <strong>Polish</strong>, <strong>of</strong> course.Then I waited for the chattering girlwho was in the phone booth to finish hereternal call. The sun was lower. The meltedsnow would be freezing again, forming slipperypatches. When was the last bus goingback? And where does it stop for me toboard?I was grateful to close the door to thephone booth, thereby ending the show forthe other patrons. I juggled my pen, notebookand Berlitz book while balancing thephone on my shoulder. I inserted the card,first upside down, then backwards, andfinally correctly, and dialed Łucja’s number.She was very surprised to hear myvoice. I was able to convey that I was at thecemetery and I wanted the “grave <strong>of</strong> hermother.” In fractured words, <strong>of</strong> course. Shethought I was at the cemetery where herhusband was buried.“No, Cmentarz Bródnowski,” I replied.“Oh, uwaga!” she exclaimed, a warningto me, as the neighborhood was not so safe.I quickly wrote the way she said the numbersfor the row and plot and the alphabetletter for the section. If only I had takentime to learn numbers in <strong>Polish</strong>, I wouldnot have had to write them phonetically tolook up in my handy book.I thanked her and tried to convey thatI would be careful. I walked back to thecemetery, energized by my newly gatheredinformation, certain <strong>of</strong> success in my quest.Section D was far into the center <strong>of</strong> anexpansive field. I stopped and looked outinto the open area beyond the trees thatlined the perimeter, seeing that only themain path was clear. The snow seemeddeeper on this side <strong>of</strong> the river. The littlemarkers for Section D were tall enough tostand out, but there had to be other lowsigns and markers for rows and plots thatI couldn’t possibly find under the snowyblanket. This blanket spread over everygrave, covering hundreds <strong>of</strong> names andidentities.There were no tall monuments, no highstones, only low plaques, all obscured bywinter’s fallen flakes. The huge fluffy whiteblanket could not be folded over to uncoverthose ever important names and dates forwhich I searched. And I could not pay myrespects at the graves <strong>of</strong> the ancestors whohad chosen not to emigrate as my grandparentshad done.I thought <strong>of</strong> many possibilities as Iwalked slowly to the bus stop, scatteringmy granola bar crumbs for the birds. Maybethe chickadees would find them.Letters to the Editor (cont’d)What a wonderful, interesting publication! Iespecially enjoyed reading “A Child’s Recollection,”which brought back memories <strong>of</strong>my childhood in Chicago. Living on Cullertonand Leavitt St. in the area with thevaulted street. Not knowing why the streetwas raised until later on in life, just acceptinglife the way it was. Living in a neighborhoodwhere everyone spoke <strong>Polish</strong> andsome speaking half-<strong>Polish</strong> and half-English.The cold water flats, Saturday night bathsin the galvanized tub. Summer eveningsitting on the front concrete porch talkingwith neighbors until bedtime. Flats withno hot water, no heat, only by coal or oilstoves, no air-conditioning, no refrigeration,and yet we survived. Could the children inthis day and age do the same?Looking forward to the next publication,keep up the good work.Loretta (Majerczyk) NemecEditor: I’m pleased you enjoyed thatarticle. I knew it was a good article when Ifound myself enjoying it—and I didn’t evengrow up in Chicago!Subject: Lithuanian Heritage magazineI just received the latest edition <strong>of</strong><strong>Rodziny</strong>. I read it cover to cover and enjoyedit greatly.<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 11

I always find the “Articles <strong>of</strong> Interest”section such a teaser that I decided tocheck the Internet for some <strong>of</strong> the publicationsmentioned. Since my great-grandparentsWincenty and Helena (Bodanowicz)Woroniecki were <strong>Polish</strong> speakers from theWilno area, I am particularly drawn to theLithuanian resources.It appears the Web address for LithuanianHeritage magazine should be www.lithuanianheritage.com (instead <strong>of</strong> .org).Thank you for the great journal.Joe Zadroznycurrently <strong>of</strong> Berlin, GermanyEditor: I appreciate your kind words,and you’re absolutely right about theproper URL for Lithuanian Heritage—a veryfine publication, incidentally. Thanks forthe correction!Subject: Galician RailroadI’m a longtime PGSA member andwanted to drop you a note to say how muchI appreciate the continuing high quality <strong>of</strong>the <strong>Rodziny</strong> journal and the articles thatappear therein. I was especially impressedwith the piece on the “Galician Railroad” byIwona in the Winter 2008 issue.Railroad development in the 19th centuryis a topic about which I would like tosee additional follow-up articles, especiallyregarding the various railroad travel routesthat were available to emigrés transitingto Atlantic seaports with ships sailing for<strong>America</strong>. It would be informative to learnsomething about the logistics <strong>of</strong> how <strong>Polish</strong>immigrants from the rural countrysidebecame aware <strong>of</strong> their travel options to<strong>America</strong>, where they bought tickets, etc. I’msure this would be <strong>of</strong> interest to many readers<strong>of</strong> <strong>Rodziny</strong>.Lastly, I would like to put in my requestfor a translation <strong>of</strong> the Słownik geograficznyentry for the regional town <strong>of</strong> Jasło insoutheast Poland. I don’t think I’ve seenthis entry translated as yet, but it’s my impressionthis is a major regional town andmight be <strong>of</strong> broad interest to PGSA members.Chet Szerlag, Woodridge, IllinoisEditor—I passed your words on toIwona, and I’m sure she’ll do what she canto give us more on this subject. She saidLe t t e r s t o t h e Ed i t o r12 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008the main sources she used on her articleare as follows:Bissaga, T.: Geografia kolejowa Polski,1938.Dzięsieciolecie Polskich KoleiPaństwowych 1918-1928, MinisterstwoKomunikacji.Golsdorf, K.: Koleje w Austrii1837-1918.Wierzbicki, L.: Rozwój sieci koleiżelaznych w Galicji,1847-1890.As for the SGKP entry for Jasło, I translatedit years ago for the <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong><strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texas, and you can read it—enhancedwith nice photos—on their Web siteat http://www.pgst.org/places/jaslo.htm.Subject: Iwona!I desire to advise you <strong>of</strong> how much Ienjoy the articles by Iwona Dakiniewicz in<strong>Rodziny</strong>. I also wish to advise you <strong>of</strong> thewonderful pr<strong>of</strong>essional relationship I havehad with her for a few years now. She hasperformed some really detailed research forme during these years, and I have alwaysbeen more than satisfied with her workperformance. In the family research she hasdone for me, she has always been diligent,thorough, helpful, and reasonable. I wish tocommend her highly to you and to anyonewho wishes to have family research and/or guide-travel-tour assistance work donefor them. She is a wonderful researcher andvery considerate.Daniel Kobylarz-HughesSubject: Germans/Poles in MemelPerhaps you can point me in the rightdirection. In doing family research, I amtrying to find facts to support a familystory.The story is that Frederick William’s(born 1801) father and mother moved toMemel from (possibly) Poland because theyhad a <strong>Polish</strong> name. His father said to thefamily that from then on, their name wouldbecome Licht (German for light) because“Now we are Germans.” They were Protestants.He was a tailor. His wife’s name wasHenrietta.In doing a bit <strong>of</strong> online research, I canguess that one <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Polish</strong> rebellions (either1794 or 1831) brought them to Memel.Or perhaps (considering his first andmiddle names) they were part <strong>of</strong> the 20,000

efugees from Salzburg, or other areas, whowere invited to settle in this region by FrederickWilliam I.Would my guesses be accurate? Do youhave any other thoughts on <strong>Polish</strong>-namedpeople in Memel during the late 1700s toearly 1800s?Thanks for any help.Joanne RodgersEditor—I can’t answer this, but perhapsone <strong>of</strong> our readers can.Subject: Where is Wrzonca?I am having trouble locating my grandfather’splace <strong>of</strong> birth in Poland, and I hopeone <strong>of</strong> the readers can help.My grandfather, Josef S. Gembicki,came to the United States in 1913. He arrivedin New York on November 6, 1913, onthe SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. He camethrough Ellis Island, his place <strong>of</strong> birth islisted as “Wrzonca, Russia/Poland.” I havechecked old maps and new maps <strong>of</strong> Poland,and I cannot find this city. I have come tothe conclusion that I am reading it wrongon the passenger record, or maybe it is misspelled.Can anyone out there help?Karen Glynn51718 Red Mill RdDowagiac MI 49047-8775Editor—I’m printing your letter inhopes other members can help more. In themeantime, I might be able to help a little.I used the Steve Morse Web site, www.stevemorse.org, to view the manifest forJosef Gembicki’s arrival in 1913, and youhave read his place <strong>of</strong> birth correctly, inmy opinion. It does indeed seem to say“Wrzonca,” and gives his country <strong>of</strong> originas “Russia”—presumably that part <strong>of</strong>Poland seized by the Russian Empire inthe late 18th century. “Wrzonca” is also theplace indicated as his previous residence.The problem is, there is no place in Polandcalled Wrzonca! But a little familiaritywith the <strong>Polish</strong> language solves that mystery.In <strong>Polish</strong>, the nasal vowel written asą is pronounced much like on, and it wasnot at all unusual for people to spell namesphonetically with on, especially if they werenot familiar with <strong>Polish</strong>. For that matter,even Poles sometimes did this. Universalliteracy is a comparatively recent developmentin Poland, and there was not alwaysLe t t e r s t o t h e Ed i t o ra consensus on the “right” way to spell aname when there was more than one phoneticallyaccurate version. So while Wrzącais the “correct” spelling these days, in olderrecords and letters it wouldn’t be odd to seeit as Wrzonca sometimes.That’s the good news. The bad newsis, there are nine places in Poland namedWrząca, and six <strong>of</strong> them were in RussianPoland. Wrząca can be a village <strong>of</strong> some 60people in Gostynin county, Mazowieckieprovince; a village <strong>of</strong> some 350 people inPabianice county, Łódzkie province (nearŁódź); a village <strong>of</strong> some 660 people in Sieradzcounty, Łódzkie province; a village <strong>of</strong>some 110 people in Kalisz county, Wielkopolskieprovince; a village <strong>of</strong> some 270people in Turek county, Wielkopolskie province;or a village <strong>of</strong> some 480 people in Kołocounty, Wielkopolskie province. There werealso places by this name in the Germanpartition, but I think you can ignore those,since the manifest says your grandfatherwas a citizen <strong>of</strong> Russia, not Germany.Without further information, there issimply no way to tell which Wrząca yourancestor came from. All I can suggest isthat you keep digging, in hopes <strong>of</strong> findingsome document that mentions the name <strong>of</strong>the nearest large town, or the county seat.That would allow you to focus in on one <strong>of</strong>those places. Otherwise, your only hope isto take them one at a time and dig around,hoping that you’ll get lucky and he camefrom the first or second one you check, notthe fifth or sixth!Incidentally, keep your eyes open als<strong>of</strong>or documents that mention people namedGębicki, because Gembicki is a variantspelling <strong>of</strong> that name. We’re dealing herewith the other <strong>Polish</strong> nasal vowel, ę, whichsounds like en usually, but before b or pmore like em. In modern <strong>Polish</strong>, Gębickiis the more common spelling; as <strong>of</strong> 1990,some 1,438 <strong>Polish</strong> citizens spelled it thatway, as opposed to 390 who spelled it Gembicki.Of those Gębickis, 198 lived in whatwas Łódź province in 1990; another 109 informer Płock province (in which the Wrzącain Gostynin county was located in 1990);and 86 in Konin province (in which currentTurek county was located in 1990). So thesurname is spread all over, and we can’tpoint to any one <strong>of</strong> those places namedWrząca and say “that’s the only place in Polandwhere we find people named Gębicki/Gembicki.”<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 13

Ask the RetoucherEric Basir He’s worked in darkrooms—both digital and conventional—newspapers and studios. He runs Photo Grafix, a humblephoto-retouching studio in Evanston, Illinois (USA), helping genealogists restore and preserve photos and documents withtheir computers. If he doesn’t know the answer, he won’t rest until he finds it. Eric Basir is at your service. With each “Ask theRetoucher” column, he’ll help you successfully tackle your digital photographic preservation and restoration problems.Please send your questions and problem photos, your location, and genealogical society affiliation (if appropriate) toquestions@abetterreality.net for future “Ask the Retoucher” columns. You can learn more about Eric and his work online atwww.abetterreality.net. He has also enhanced many <strong>of</strong> the photos in issues <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rodziny</strong>. Thanks, Eric!Question—Tom (USA) asks: “I haveheard about various clear sprays that aredesigned to protect color photos againstUV damage. How effective are these sprays,and can you suggest one or two that workespecially well?”Answer—Tom, I have had no experiencewith any UV protection sprays. I treatUV sprays the same way I do nutritionalsupplements: they might help prevent problems,but—in many cases—they are not asgood as a commonsense diet with exercise.You certainly deserve a more detailedexplanation, since your photos don’t eat ormove. So, a commonsense diet with exercisefor your photos would be:1. Keep them out <strong>of</strong> sunlight. Period.That is, direct or indirect sunlight.2. Keep them behind a glass framewith matt-board.3. Use archival-quality framing materials.4. Keep them away from any kind <strong>of</strong>smoke or moisture.5. Use real photographic prints(which can be done even with digital images).If you use an inkjet printer, useonly the manufacturer’s ink and paper;HP ink and paper for HP printers, forexample.If you do all <strong>of</strong> these things, I don’t believeyou’ll need the UV spray. You will alsosave money, your lungs, and the environmentby not using the spray. Regarding theframe, I highly recommend a pr<strong>of</strong>essionalframing service or archival and/or scrapbooksupply service. They are trained in thelatest archival techniques and use the bestquality supplies. In the worst case, you canpurchase a frame with its own matt-boardfrom a local retail store.Question—Lee (USA) asks: “I have avast amount <strong>of</strong> picture albums that I wouldlove to put on CDs for sake <strong>of</strong> space. WhichCD is the best? The CD-R or the CD-RW? Ihave heard that after a few years they willnot be gone from the CD. Is this true?”Answer—Lee, all recording media evolvethroughout the years. From stone tablets,cave walls, and papyrus to audiocassette,CD, and flash memory, the best way topreserve them is to transfer to the latesttechnology and create multiple copies.This should include digital and hard copy(prints) or analog (tape). It sounds a bitfanatical—having various copies <strong>of</strong> everything—butit’s worth it.Organizing it can become a headache,however. So it’s important to start out withthe basics before establishing an elaboratearchiving system. The most basic systemshould consist <strong>of</strong> an external hard-drivewith almost twice the capacity <strong>of</strong> your computer’shard-drive and a high-quality DVDwriter. First, copy your entire photo archiveonto the external drive. Then, transfer thecollection onto CDs or DVDs, as appropriate.I also recommend you create one extracopy <strong>of</strong> each CD or DVD <strong>of</strong> your photos andstore the extra copies in another locationoutside <strong>of</strong> your home. This process willgreatly reduce the risk <strong>of</strong> losing your collection.I suggest using DVD-R for archivingfamily photos. I’m only recommendingDVD-R because its capacity is six times thecapacity <strong>of</strong> a CD-R. CDs can hold about650 megabytes. DVDs can hold about 4,500megabytes. Besides that, either one shouldwork fine. Avoid using RW (rewritable)media because the surface is not stableenough for archival purposes. The slightestscratch or sneeze might render it useless(smile).I use CD-RW and DVD-RW for sharingfiles and burning MP3s for playing music(which I then later overwrite, since all the14 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008

As k t h e Re t o u c h e roriginals are on my computerand backup drives).There is an emerging duallayer DVD technology alsoavailable. These DVDs arerecordable on both sides,thus increasing their capacitytw<strong>of</strong>old, from fourgigabytes to eight. However,because they’re so new,I don’t recommend usingthem for your archives atthis time.Finally, I recommendyou read the “CD LongevityNotes” on our Web site. Goto http://www.abetterreality.net,click on “Ask the Retoucher,” and look forthe file in “Downloads for our Readers.” Inthis folder, you’ll find articles from variouspoints <strong>of</strong> view about CDs and DVDs.Housekeeping note for our readers: Toimprove distribution <strong>of</strong> downloadable content,we have moved our files to differentservers. So any links in past articles willnot work. Everything has been moved to the“Ask the Retoucher” section at http://www.abetterreality.net.Please send an e-mail messageto if a fileyou need is not in the downloads list.Please do not duplicate, publish, ordistribute this article without permissionfrom Photo Grafix. This article is exclusivelydistributed to specific publications throughour own syndication process. Adobe Photoshopand Adobe Photoshop Elements © 2007Adobe Systems Incorporated.ATTENTION ALL PGSA MEMBERSThe PGSA Board needs your help and support in selecting the recipients <strong>of</strong> the Wigilia and GwiazdaAwards for 2008. As you know, the PGSA recognizes the work <strong>of</strong> an outstanding individual or an institutionat our annual meeting. There is a strong feeling that we need more input from our membershipin finding those worthy <strong>of</strong> these honors. Please help us by suggesting people for each <strong>of</strong> these awards.Simply submit a nomination letter in which you describe your reasons, in as much detail as possible,for selecting your candidate. Indicate for which award(s) you are nominating the individual. Also, let usknow how to contact you, if we have any questions. Please send the nomination letter to:Richard Stanowski, PGSA Awards Chairperson, 1648 Ash Avenue, Woodstock, IL, 60098-2589Another option is to submit your selection to the Awards Chairperson via e-mail: .We need your selection(s) no later than April 30, 2008. If you have any questions, you may also contactRichard Stanowski at 815-337-5835. The basic guidelines are given in the following paragraphs:Annually, the PGSA Board selects a recipient <strong>of</strong> the Wigilia Award for outstanding service to the field<strong>of</strong> <strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>n genealogical research. It is given to an individual who has made, over a period <strong>of</strong>time, noteworthy contributions to the field. The award may also be given to a public or private institutionthat has made a significant contribution to <strong>Polish</strong>-<strong>America</strong>n genealogy.A second award, known as the Gwiazda Award, is given to a volunteer who has given freely <strong>of</strong> his orher time and talents to the <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Genealogical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>. The recipient should be someonewho has a record <strong>of</strong> meritorious service to the <strong>Society</strong>, is supportive <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Society</strong>’s goals and endeavors,and can be depended on to successfully complete any task undertaken.<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 15

FOLLOW-UP TO IWONA’S GALICIAN RAILROAD ARTICLEI want to tell you how delighted I wasto read about the Galician railroad in theWinter 2008 edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rodziny</strong>. My fatheralways told me that my grandfather workedas a carpenter for the railroad in the erabefore World War I, but I knew very littleelse about it.One thing that your article did not mentionis that railroad employees and theirfamilies were given passes for riding on therailroad. I don’t remember my father sayingwhether these were “free rides” or just reducedfare. What makes them very specialto me is that they were photo IDs. They arethe only photographs I have <strong>of</strong> my paternalgrandparents, Antoni and Katarzyna (neeSanecka) Wolan, and one <strong>of</strong> the few childhoodphotos <strong>of</strong> my father, Julian. You cansee that my grandfather’s photo/pass wasused because it shows creasing and morewear than the others. My father recalledthat he was about seven or eight whenthe photo was taken, which would make itabout 1918. He said my grandfather workedfor the railroad before and during WorldWar I, starting about 1910. They lived in asmall village just outside the small town <strong>of</strong>Strzyżów in what was then Rzeszów province,where they had a farm.Margaret Wolan Sullivan 16 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008What makes them passes is the <strong>of</strong>ficialstamp <strong>of</strong> the National Railroad, which youcan see in the attached scans. With these,the family were able to travel from nearStrzyżów to Kraków, where two older brotherslived and worked, and presumably toreceive visits in return.Margaret Wolan Sullivan

MY GREAT-GREAT-GRANDMOTHER WAS AN ENEMY ALIEN!!Kenneth P. Nowakowski On May 5, 1891, the first <strong>of</strong> my directancestors to arrive in <strong>America</strong>, mygreat-grandparents, Jan and AgnieszkaWardyński, with their six-month-old daughterStanisława, disembarked the NorddeutscherLloyd passenger liner Karlsruhe,were ferried from the pier in Hoboken, NewJersey, to the southern tip <strong>of</strong> Manhattan,and filed through Castle Garden. They hadleft a rural existence in the Poznań area<strong>of</strong> Prussian Poland to seek freedom in theUnited States to carry on their <strong>Polish</strong> traditionswithout the restrictions imposed uponthem by German autocrats. Their namesas listed in the manifest <strong>of</strong> the Germanship were Johann and Agniska Wardenski.Although in the ship’s records they bothwere declared as farmers, they would soonreinvent themselves when they arrived bytrain in the state <strong>of</strong> Illinois.They settled in the twin towns <strong>of</strong> Peru-LaSalle, located on the northern bank <strong>of</strong> theIllinois River in LaSalle County about onehundred miles west-southwest <strong>of</strong> Chicago,where a large <strong>Polish</strong> population was alreadybeginning to thrive. They chose this area astheir home and remained there for the rest<strong>of</strong> their lives. St. Hyacinth, a <strong>Polish</strong> RomanCatholic Church, was founded in LaSalle in1875 as an alternative parish to St. Joseph’sin Peru, which was mostly attendedby those <strong>of</strong> German descent. Now the Poleswho settled in the Illinois River Valley hada religious institution that <strong>of</strong>fered Massin their native tongue. After the originalchurch was consumed by fire in 1890, anew building was completed the followingyear—the same year that the Wardynskisarrived (since they were now <strong>America</strong>ns, Isuppose we should drop the accent fromthe n). The new red brick Gothic-stylebuilding stood proud and tall on 10thStreet. Its twin steeples with bells namedfor the three <strong>Polish</strong> saints, Hyacinth,Stanisław, and Wojciech, rang out to call allthe <strong>Polish</strong> families in the area to Mass.Unfortunately, the first religious ceremonyperformed in the church for theWardynski family in the year <strong>of</strong> their arrivalwas a funerary mass for their baby daughter,Stanisława, who took sick and died onSeptember 14, 1891. She was buried inan unmarked grave in St. Hyacinth Cemetery.This had to be a devastating timefor 20-year-old Agnes and her 25-year-oldhusband. But now, every child born to thecouple would be born on <strong>America</strong>n soil.On March 10, 1892, Agnes gave birthto another daughter, Josephine. Shewas raised as a small-town girl with anall-<strong>America</strong>n attitude toward life and awarm and pleasant disposition that madeeveryone who met her feel at ease. Butshe was truly a child <strong>of</strong> two worlds; shecould read, write, and speak <strong>Polish</strong> withthe best <strong>of</strong> the newly arriving immigrants.This child, who the family nicknamedJosie, would grow up to marry an ungainly<strong>Polish</strong> immigrant named WładysławNowakowski, and the two <strong>of</strong> them wouldraise a family <strong>of</strong> eight children, the second<strong>of</strong> which was my father, Chester, who wasborn in Peru in 1910. It wasn’t until 1926that Władysław, now known as Walter,and Josephine decided that perhapsemployment opportunities in the big city <strong>of</strong>Chicago appeared more hopeful, and theyand their family, which now numberedseven children, left Peru. Over the years,some <strong>of</strong> the Wardynski brothers and sistersmoved to and settled in other Illinois towns,and some left to raise their children in thebig cities <strong>of</strong> other states; but only Josephinemoved her family to Chicago.In the 1950s, I remember my greatgrandfather,John Wardynski, from tripsdown to Peru with my grandmother. Therewere weddings and funerals, a familypicnic, and great-grandpa’s 90th birthdayparty in October <strong>of</strong> 1955. John Wardynskiwas a small, iconic figure <strong>of</strong> a man aroundwhom family members were always eagerto gather for picture taking. And well theymight have, since without him all <strong>of</strong> uswouldn’t have been here. As a child, I couldnever approach him without apprehension;this man was genuine family royalty. Whenattending the wake for my grandmother’sbrother, Bernard, at the Ptak Funeralparlor in Peru in March <strong>of</strong> 1956, my fatherwalked up to his grandfather and, seeingthe saddened look on his face, tried to cheerhim. John Wardynski looked up from thedeeply upholstered chair in which he was<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 17

My Gr e a t-Gr e a t-Gr a n d m o t h e r Wa s a n En e m y Al i e n!!At right: A photo <strong>of</strong>the house at 1325Walnut St. Below:A Wardynski familypicnic. All photoscourtesy <strong>of</strong> theauthor.seated and said, “I am not so much mourningthe death <strong>of</strong> my son as I am worriedabout outliving all my children. Will therebe anyone left to see me to my grave whenI die?” This was a man who truly loved hisfamily. He died on January 19, 1963, at theage <strong>of</strong> 97; he had outlived two wives and allbut five <strong>of</strong> his thirteen children.In working on the family genealogy, Ihave developed a special appreciation formy great-grandfather. He accomplished allthat other <strong>Polish</strong> immigrants did in theirrelocations to the United States, but withan amazing speed <strong>of</strong> purpose and unerringdirection. In the 1894 city directory hewas listed as already working for the IllinoisZinc Co., one <strong>of</strong> the largest employers in thearea. The company operated a huge rollingmill on the riverfront that manufactured18 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008sheets <strong>of</strong> zinc and ran mines that providedcoal for its blast furnaces. On June 12th,1897, with three children already addedto his family, John Wardynski signed topurchase a lot from the Roman Catholicchurch in what would soon be the FirstWard <strong>of</strong> the town <strong>of</strong> Peru. The church hadalready built a school building in 1891, andin September <strong>of</strong> 1899 the <strong>Polish</strong> Church <strong>of</strong>St. Valentine’s was completed just one half<strong>of</strong> a block from the Wardynskis’ new homeon 1325 Walnut St. Now, both Peru and La-Salle had churches <strong>of</strong>fering services in <strong>Polish</strong>.Soon that ward, located between a ravineand the eastern town line that abuttedthe western limits <strong>of</strong> LaSalle, would becomea <strong>Polish</strong> community where bartenders andshop owners could welcome the hard-workinglaborers into their establishments withan enthusiastic “Dzień dobry!” John mightstop for a beer at Kulikowski’s Saloon whileAgnes could shop at Urbanowski’s Grocery,Meat, and Hardware Store. In October <strong>of</strong>1904, John Wardynski’s naturalizationpapers were finalized at the County Courtbuilding in the town <strong>of</strong> Ottawa, and he andAgnes could proudly acclaim themselves as<strong>America</strong>n citizens.On April 12, 1894, the SS Amerikaarrived in Baltimore Harbor with six passengersaboard who had declared theirdestination in the United States as Peru,Illinois. Jan and Michalina Skrzypczak werethe parents <strong>of</strong> Agnes Wardynski. With them

My Gr e a t-Gr e a t-Gr a n d m o t h e r Wa s a n En e m y Al i e n!!came her four younger sisters, Katha, Marianna,Magdalina, and Josepha. I’m surethat John and Agnes provided some or all <strong>of</strong>the money needed to finance their trip. Thefamily had sailed from the port <strong>of</strong> Hamburgafter leaving a village named Topola on theoutskirts <strong>of</strong> środa.Today, with only a few <strong>of</strong> my aunts andno uncles still living, the Skrzypczaks werepretty much a forgotten family. MichalinaSkrzypczak had first introduced herselfto me in the early days <strong>of</strong> my genealogicaljourneying when I was on one <strong>of</strong> my latenighttreks through ancestry Web sites. Iwas delving into the 1920 census takenin the town <strong>of</strong> Peru, Illinois, when this77-year-old woman appeared as the lastentry in a list <strong>of</strong> family members living at1501 Walnut St. This was the residence <strong>of</strong>my grandmother’s sister, Pearl, who livedthere with her husband, Joseph Wyciskalla,and their three young children, Edmund,Joseph, and Mary. That census listedMichalina as a boarder who had arrived in<strong>America</strong> in 1894 and was never naturalized.Two things first came to my mind whenI discovered this household shared by aSkrzypczak and the Wyciskalla family.First, this address had to be a nightmarefor postal delivery. Wyciskalla is a difficultenough name, but Skrzypczak is a pronunciationnightmare devoid <strong>of</strong> almost everyvowel. It is misspelled at the rate <strong>of</strong> about80 percent whenever it appears in legaldocuments, city directories, and newspaperobituaries. One must never assume thatone can find this name in any form similarto its proper spelling. The second thingcame in the form <strong>of</strong> a question. Why wasthis elderly lady living in the residence <strong>of</strong>my Great Aunt Pearl, who was obviouslybusy building a family in the early years <strong>of</strong>her marriage? My assumption was that shehad to be a close relative.Over the years, I was able to unearthall the ships’ manifests, the baptismal andmarriage records, and the governmentpapers that substantiated the Skrzypczaks’relationship to my great-grandparents. Theywere my only great-great-grandparents tohave emigrated from Poland and settledhere in the United States.But then, one night about a half-yearago, while I again was surfing the Net,checking out sites that might disclose theWardynskis’ origins in German Poland, Ityped the their name into Ancestry.com andbegan scrolling down through the differentareas. Eventually I came to AncestryWorld Trees and, to my surprise, the namesJohn and Michalina Skrzypczak appeared.And though that surname was misspelled(Skszypczak), I knew that this couple linkedwith the names <strong>of</strong> John Wardynski andhis wife Agnes Skrzypczak added up to mygrandmother’s parents and grandparents.And not only was Michalina listed butalso her parents, Joseph Maciejewski andBrigida Wozniak.In what turned out to be the greatestfreebie <strong>of</strong> my probing into the past, I realizedthat someone had handed me thenames <strong>of</strong> my great-great-great-grandparents.My next step was to discover whohad taken the time to construct this familytree online. After spinning around throughseveral revolving doors, I came up with thename Mary Zukowski, who lived in La-Salle, Illinois. Because <strong>of</strong> the research I hadbeen doing in the LaSalle-Peru area, I hadbecome a member <strong>of</strong> the LaSalle CountyGenealogy Guild. The guild is located onGlover Street, just a few blocks south <strong>of</strong>the Illinois River, in a great little buildingfilled with library tables that <strong>of</strong>fers lots <strong>of</strong>area for research, a plethora <strong>of</strong> old booksand documents (church records, city directories,obituaries, micr<strong>of</strong>ilms), and anexceptionally helpful staff. I first became amember <strong>of</strong> this organization in 2002. SinceMary Zukowski lived in LaSalle and wasgenealogically astute, I assumed that shewas a fellow member <strong>of</strong> this organization,and in searching through the Guild’s 2006Surname Index, I found her listed as member# 43. I am member # 4033. I obtainedMary’s address from the Guild Index andthen looked up her phone number in theLaSalle-Peru telephone directory.Each step in this genealogical discoveryprocess would bring me nearer to myunderstanding <strong>of</strong> the Wardynskis. Thisfamily bypassed the opportunities <strong>of</strong> settlingin the big city <strong>of</strong> Chicago where therewas an abundance <strong>of</strong> jobs and housing.Instead they opted to come to the town <strong>of</strong>Peru, Illinois. Why? In May <strong>of</strong> 1891, whenJan and Agnieszka arrived in the Midwest,a great white city was being constructedin Jackson Park on the southernmost citylimits <strong>of</strong> Chicago that two years later wouldopen as the World’s Columbian Exposition.Chicago was crying out for immigrant labor!Why didn’t the Wardynskis follow the over-<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 19

My Gr e a t-Gr e a t-Gr a n d m o t h e r Wa s a n En e m y Al i e n!!Registration card, with photograph, <strong>of</strong> the enemy alien (see page 22).whelming tangle <strong>of</strong> steel rails into Chicagoinstead <strong>of</strong> heading southwestward into theIllinois River Valley?In my late Tuesday morning telephoneconversation with Mary Zukowski, all myquestions were answered. Mary had beeninvolved in researching her family genealogyfor 25 years. I found out that hergrandfather, Wojciech Maciejewski, hadbeen born on March 27, 1853, in the tinytown <strong>of</strong> Brzeziak, in the parish <strong>of</strong> Mączniki,which was located near środa, a city justsoutheast <strong>of</strong> Poznań. He emigrated in 1880and settled in LaSalle, Illinois. On November16, 1884, he married Mary Gniewkiewskiat St. Hyacinth’s Church in LaSalle.Mary Zukowski’s father, John, was born in1887 in Peru as the second <strong>of</strong> their children.Mary’s father wed Sophie Tomaszewskiin 1913, and Mary was born in 1926.But Wojciech—or Albert, as he was later20 <strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008known—was the maternal uncle <strong>of</strong> AgnesWardynski. After he had come to Peru, Illinois,he most likely exchanged letters withhis sister Michalina Skrzypczak, who stillresided in the Poznań area <strong>of</strong> Poland. Thoseletters probably were filled with the promise<strong>of</strong> many job opportunities that awaitedmembers <strong>of</strong> the family in the Illinois Riverregion <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong>, and most likely led to theemigration <strong>of</strong> Jan and Agnieszka in 1891,and eventually <strong>of</strong> Agnieszka’s parents, Janand Michalina Skrzypczak, and their fouryounger daughters, in 1894.Several weeks after our conversation,a packet arrived at my door with informationon the Maciejewski family. Mary and Ishared the ancestors Joseph Maciejewskiand Brigida Wozniak. They were her greatgrandparentsand my great-great-greatgrandparents,which makes us secondcousins, twice removed. Of them and their

My Gr e a t-Gr e a t-Gr a n d m o t h e r Wa s a n En e m y Al i e n!!10 children, only Michalina and Wojciechhad come to the United States. Includedin the paperwork were charts for the families<strong>of</strong> Joseph and Brigida Maciejewski andWojciech and Mary Maciejewski, with birth,death, and marriage dates and town namesfor all these events in their children’s lives.Mary and I have kept up a correspondencenow for about five months. I senther ship’s records that I had found for theWardynskis and the Skrzypczaks and alsoa copy <strong>of</strong> a photo <strong>of</strong> Agnes Wardynski andfour <strong>of</strong> her children that had been taken inthe front <strong>of</strong> their house on Walnut Streetin Peru circa 1905. She recently mailedme an obituary for Helen Noramczyk, whodied in Peru on November 14, 2007, at theage <strong>of</strong> 99; she was the second wife <strong>of</strong> mygrandmother’s brother John Wardynski. Inreading through the death notice, I foundthat my father’s cousin, Romana Jasiek,and her husband, Stanley, are still livingPages from the registration booklet.in Peru. After I told my father’s youngestsister, Frances Kempa, about this, she senta letter to their residence and received afriendly reply. I feel as if a lot more genealogicalinformation is on the way now that Ihave contacts in the towns where my fatherand my grandmother were born and raised.When Michalina Skrzypczak and herhusband John arrived in 1894, he was 60years old and she was 52. Mary Zukowskitold me that even though he was <strong>of</strong> anadvanced age, he accepted employmentin a coal mine where he later became thevictim <strong>of</strong> some on-the-job injury. For a longperiod <strong>of</strong> time, with John unable to work,the couple depended on their family forsupport, and there is even some indicationthat they lived out <strong>of</strong> state in Missouri withone <strong>of</strong> their daughters for a few years. Butthey were back in Peru when John died onNovember 20, 1910. After this, Michalinamust have moved in with the Wardynskis,<strong>Rodziny</strong>, Spring 2008 21