The Impact of Providing Incentives for Attendance at AIDS ...

The Impact of Providing Incentives for Attendance at AIDS ...

The Impact of Providing Incentives for Attendance at AIDS ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

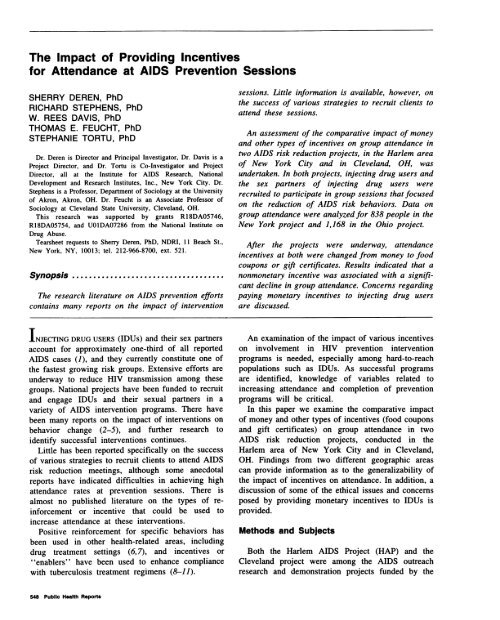

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Impact</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Providing</strong> <strong>Incentives</strong><strong>for</strong> <strong>Attendance</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> Prevention SessionsSHERRY DEREN, PhDRICHARD STEPHENS, PhDW. REES DAVIS, PhDTHOMAS E. FEUCHT, PhDSTEPHANIE TORTU, PhDDr. Deren is Director and Principal Investig<strong>at</strong>or, Dr. Davis is aProject Director, and Dr. Tortu is Co-Investig<strong>at</strong>or and ProjectDirector, all <strong>at</strong> the Institute <strong>for</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> Research, N<strong>at</strong>ionalDevelopment and Research Institutes, Inc., New York City. Dr.Stephens is a Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Department <strong>of</strong> Sociology <strong>at</strong> the University<strong>of</strong> Akron, Akron, OH. Dr. Feucht is an Associ<strong>at</strong>e Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>Sociology <strong>at</strong> Cleveland St<strong>at</strong>e University, Cleveland, OH.This research was supported by grants R18DA05746,R18DA05754, and U01DA07286 from the N<strong>at</strong>ional Institute onDrug Abuse.Tearsheet requests to Sherry Deren, PhD, NDRI, 11 Beach St.,New York, NY, 10013; tel. 212-966-8700, ext. 521.Synopsis ....................................<strong>The</strong> research liter<strong>at</strong>ure on <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention ef<strong>for</strong>tscontains many reports on the impact <strong>of</strong> interventionsessions. Little in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion is available, however, onthe success <strong>of</strong> various str<strong>at</strong>egies to recruit clients to<strong>at</strong>tend these sessions.An assessment <strong>of</strong> the compar<strong>at</strong>ive impact <strong>of</strong> moneyand other types <strong>of</strong> incentives on group <strong>at</strong>tendance intwo <strong>AIDS</strong> risk reduction projects, in the Harlem area<strong>of</strong> New York City and in Cleveland, OH, wasundertaken. In both projects, injecting drug users andthe sex partners <strong>of</strong> injecting drug users wererecruited to particip<strong>at</strong>e in group sessions th<strong>at</strong> focusedon the reduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> risk behaviors. D<strong>at</strong>a ongroup <strong>at</strong>tendance were analyzed <strong>for</strong> 838 people in theNew York project and 1,168 in the Ohio project.After the projects were underway, <strong>at</strong>tendanceincentives <strong>at</strong> both were changed from money to foodcoupons or gift certific<strong>at</strong>es. Results indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> anonmonetary incentive was associ<strong>at</strong>ed with a significantdecline in group <strong>at</strong>tendance. Concerns regardingpaying monetary incentives to injecting drug usersare discussed.INJECTING DRUG USERS (IDUs) and their sex partnersaccount <strong>for</strong> approxim<strong>at</strong>ely one-third <strong>of</strong> all reported<strong>AIDS</strong> cases (1), and they currently constitute one <strong>of</strong>the fastest growing risk groups. Extensive ef<strong>for</strong>ts areunderway to reduce HIV transmission among thesegroups. N<strong>at</strong>ional projects have been funded to recruitand engage IDUs and their sexual partners in avariety <strong>of</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> intervention programs. <strong>The</strong>re havebeen many reports on the impact <strong>of</strong> interventions onbehavior change (2-5), and further research toidentify successful interventions continues.Little has been reported specifically on the success<strong>of</strong> various str<strong>at</strong>egies to recruit clients to <strong>at</strong>tend <strong>AIDS</strong>risk reduction meetings, although some anecdotalreports have indic<strong>at</strong>ed difficulties in achieving high<strong>at</strong>tendance r<strong>at</strong>es <strong>at</strong> prevention sessions. <strong>The</strong>re isalmost no published liter<strong>at</strong>ure on the types <strong>of</strong> rein<strong>for</strong>cementor incentive th<strong>at</strong> could be used toincrease <strong>at</strong>tendance <strong>at</strong> these interventions.Positive rein<strong>for</strong>cement <strong>for</strong> specific behaviors hasbeen used in other health-rel<strong>at</strong>ed areas, includingdrug tre<strong>at</strong>ment settings (6,7), and incentives or"enablers" have been used to enhance compliancewith tuberculosis tre<strong>at</strong>ment regimens (8-11).An examin<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the impact <strong>of</strong> various incentiveson involvement in HIV prevention interventionprograms is needed, especially among hard-to-reachpopul<strong>at</strong>ions such as IDUs. As successful programsare identified, knowledge <strong>of</strong> variables rel<strong>at</strong>ed toincreasing <strong>at</strong>tendance and completion <strong>of</strong> preventionprograms will be critical.In this paper we examine the compar<strong>at</strong>ive impact<strong>of</strong> money and other types <strong>of</strong> incentives (food couponsand gift certific<strong>at</strong>es) on group <strong>at</strong>tendance in two<strong>AIDS</strong> risk reduction projects, conducted in theHarlem area <strong>of</strong> New York City and in Cleveland,OH. Findings from two different geographic areascan provide in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion as to the generalizability <strong>of</strong>the impact <strong>of</strong> incentives on <strong>at</strong>tendance. In addition, adiscussion <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the ethical issues and concernsposed by providing monetary incentives to IDUs isprovided.Methods and SubjectsBoth the Harlem <strong>AIDS</strong> Project (HAP) and theCleveland project were among the <strong>AIDS</strong> outreachresearch and demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion projects funded by the548 Public Health Reports

N<strong>at</strong>ional Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in 63loc<strong>at</strong>ions throughout the United St<strong>at</strong>es beginning in1987. HAP oper<strong>at</strong>ed in the community from 1989through 1991, and the Cleveland project oper<strong>at</strong>edfrom 1989 until 1992. IDUs and the sex partners <strong>of</strong>IDUs (not necessarily partners <strong>of</strong> the IDUs in thegroups) were recruited to particip<strong>at</strong>e in both <strong>AIDS</strong>risk reduction intervention projects. Baseline and6-month followup interviews were conducted.Participants in both projects were administered the<strong>AIDS</strong> Initial Assessment Interview (AIA), whichcollected d<strong>at</strong>a on many topics, including demographics,drug use, needle use behaviors, and sexualbehaviors. Test-retest reliabilities <strong>for</strong> risky sexualbehaviors and use <strong>of</strong> injected drugs ranged from .66to .86, according to a 1991 personal communic<strong>at</strong>ionfrom NOVA Research <strong>of</strong> Bethesda, MD. Cashincentives <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong>tendance were used initially in bothprojects. <strong>The</strong>n, because <strong>of</strong> changes in NIDA policy,different incentives were used in both projects. Thisprovided the opportunity <strong>for</strong> examining the impact <strong>of</strong>incentives on <strong>at</strong>tendance.<strong>The</strong> Harlem <strong>AIDS</strong> project. For the Harlem project,IDUs and the sexual partners <strong>of</strong> IDUs were recruitedfrom the streets and from the obstetricalgynecologicalclinics <strong>of</strong> Harlem Hospital. Clientswere brought to one <strong>of</strong> three field sites in the Harlemcommunity to be interviewed and then were assignedto <strong>at</strong>tend a standard <strong>AIDS</strong> educ<strong>at</strong>ion group session(usually within 1-2 days <strong>of</strong> the interview). Thissession included discussion <strong>of</strong> modes <strong>of</strong> transmissionand methods <strong>of</strong> prevention. <strong>The</strong> <strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong> was composed<strong>of</strong> didactic present<strong>at</strong>ion, discussion, and an<strong>AIDS</strong> film. After this session, they were randomlyassigned either to the standard intervention condition(after which they <strong>at</strong>tended no additional sessions), orto an enhanced intervention condition, (after whichthey were asked to <strong>at</strong>tend two additional sessions).<strong>The</strong> enhanced intervention program was designedto teach specific behavioral skills needed to practicerisk reduction, including needle cleaning, condomuse, and the negoti<strong>at</strong>ion skills necessary to practicethese risk reduction behaviors. Deren and coworkersprovide more detail on the content <strong>of</strong> the groupsession (3).At the outset, clients were given a $15 moneyorder <strong>for</strong> an initial interview and a $10 money order<strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong>tendance <strong>at</strong> each group session. <strong>Providing</strong>money to clients <strong>for</strong> the interview was perceived aspayment <strong>for</strong> their time spent in particip<strong>at</strong>ion in theresearch aspects <strong>of</strong> the study and was continuedthroughout the project. Money orders were usedinstead <strong>of</strong> cash as a security precaution, so as not tokeep cash <strong>at</strong> the field site. When money orderpayment <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong>tendance <strong>at</strong> group sessions was nolonger permitted, clients were given a $10 foodcoupon, redeemable <strong>at</strong> local supermarkets.Client recruitment began in two research sites inHarlem in May 1989. A policy change regardingincentives occurred in September 1989. Followupinterviewing began in December 1989, with recruitmentcontinuing through December 1990. A total <strong>of</strong>1,770 clients were recruited <strong>at</strong> three research sites.For the purposes <strong>of</strong> this paper, the recruitment period<strong>of</strong> May 1, 1989, through December 1, 1989, wasselected. Since followup interviewing began inDecember, focusing on this time period elimin<strong>at</strong>esany changes th<strong>at</strong> may have come from adding afollowup component, such as longer delays betweenscheduled groups, as well as any changes due toinclement winter we<strong>at</strong>her.<strong>The</strong> Cleveland project. <strong>The</strong> Cleveland projectconsisted <strong>of</strong> outreach into the drug-using neighborhoodsby project workers. All clients were brought tosites where they were interviewed and then given astandard intervention session assignment. <strong>The</strong> clientwas given $10 <strong>for</strong> agreeing to be interviewed,although the payment was made <strong>at</strong> the end <strong>of</strong> thestandard intervention. Thus, unlike the New Yorkproject, all clients who were interviewed were assignedto a standard intervention session conductedon the same day. <strong>The</strong> standard intervention consisted<strong>of</strong> viewing <strong>of</strong> an <strong>AIDS</strong> educ<strong>at</strong>ion film, a brief review<strong>of</strong> fundamental knowledge about <strong>AIDS</strong>, the risks <strong>of</strong>contracting <strong>AIDS</strong> through needle use and risksinvolving sexual behavior. Clients were taught how tobleach needles and properly use condoms.Upon completion <strong>of</strong> the standard interventionsession, clients were randomly assigned either to thestandard intervention group (after which they <strong>at</strong>tendedno additional sessions) or to an enhancedintervention group. <strong>The</strong> enhanced intervention condi-July-August 1994, Vol. 109, No. 4 549

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics, by percentages,<strong>of</strong> clients recruited in two time periods with differentincentives to New York <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectTime 1 Time 2(5/1-8/31/89) (9/1-12/1/89)Characteristic Money orders Food coupons Significance'N .............. 498 340 ...Sex:Male ............. 58 55 NSFemale .......... 42 45...Age (mean years).. 37.7 36.4 P < .05Ethnicity:Afrcan American. . 93 83 P < .001Hispanic ......... 5 13 ...Other ............ 2 4 ...Target popul<strong>at</strong>ion:IDUs ............. 80 80 NSSex partners <strong>of</strong>IDUs ........... 20 20 NSEmployed .......... 10 7 NSHigh schoolgradu<strong>at</strong>e ......... 53 55 NSResidence:Own home ....... 31 25 P

clients interviewed from May 1 to December 1 <strong>at</strong>tended<strong>at</strong> least one group session. <strong>The</strong> impact <strong>of</strong>changing incentives from money orders to foodcoupons <strong>for</strong> group <strong>at</strong>tendance is shown in table 3.<strong>The</strong>re was a significant difference in <strong>at</strong>tendance withthe changed incentive. During the period when the incentivewas the money order, 83 percent <strong>of</strong> all clientswho were interviewed returned <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong> least one groupsession; when food coupons were used, 66 percent <strong>of</strong>clients returned <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong> least one session (P < .001).Of the 635 clients who <strong>at</strong>tended group sessions,288 (45 percent) were randomly assigned to thestandard intervention and 347 (55 percent) assignedto the enhanced intervention condition. Comparisons<strong>of</strong> client characteristics <strong>for</strong> those assigned to theenhanced and standard conditions indic<strong>at</strong>es similarity<strong>of</strong> client characteristics and risk behaviors. Table 3provides in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion on the rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between theincentive used and <strong>at</strong>tendance <strong>at</strong> the enhancedsessions. When money orders were used, 74 percent<strong>of</strong> those assigned to enhanced groups completed bothsessions; when food coupons were used, 58 percent<strong>at</strong>tended both enhanced sessions (P < .01). Analysesby age, ethnicity, and residential st<strong>at</strong>us indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong>these variables had no significant impact on theresults, th<strong>at</strong> is, <strong>at</strong>tendance declined with food couponsacross all c<strong>at</strong>egories.D<strong>at</strong>a were examined to see if there were any interactionsbetween client characteristics and incentive ongroup <strong>at</strong>tendance. No significant differences werefound <strong>for</strong> any client characteristics except <strong>for</strong>ethnicity. When money orders were used, 83 percent<strong>of</strong> African Americans returned <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong> least one group,compared with 78 percent <strong>of</strong> Hispanics (not significant).When food coupons were used, however, 69percent <strong>of</strong> African Americans returned <strong>for</strong> <strong>at</strong> leastone group, compared to 42 percent <strong>of</strong> Hispanics(P < .001). Thus, although there was a reduction in<strong>at</strong>tendance <strong>for</strong> both groups <strong>of</strong> clients when theincentive changed from money orders to foodcoupons, the gre<strong>at</strong>est reduction, by almost half,occurred in the Hispanic sample.Table 2. <strong>AIDS</strong>-rel<strong>at</strong>ed risk behaviors, by percentages, <strong>of</strong>clients recruited in two time periods with different incentivesto New York <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectTime 1 Time 2money foodBehavior orders coupons Significance'Injected drug use (IDUs only):2Heroin ........................ 39 43 NSCocaine ...................... 43 48 NSSpeedball ..................... 38 43 NSNoninjected drug use:2Alcohol ....................... 43 42 NSCrack ......................... 50 53 NSCocaine ...................... 24 18 P < .05Heroin ........................ 16 19 NSCondom use (percent <strong>of</strong> timeused):Single sex partner ............. 17 17 NSMultiple sex partners .......... 35 36 NS' Chi-square tests were used <strong>for</strong> all significance tests involving c<strong>at</strong>egoricald<strong>at</strong>a; t tests were used <strong>for</strong> comparisons <strong>of</strong> means.2Mean monthly frequency.Table 3. <strong>Attendance</strong> <strong>at</strong> standard and enhanced groupsessions by incentive, New York <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectMoney ordersFood coupons<strong>Attendance</strong> Number Percent Number Percent Significance'Cleveland project. A total <strong>of</strong> 1,168 clients wererecruited from April 25, 1989, through November 30,1990. Of the total, 957 were recruited when theincentive was cash, and 211 particip<strong>at</strong>ed after theincentive was changed to a supermarket gift certific<strong>at</strong>e.Demographic characteristics <strong>of</strong> the groups arepresented in table 4. As in the New York sample, amajority <strong>of</strong> the Cleveland sample were male (73percent) and injecting drug users (69 percent).<strong>The</strong>re were significant differences in the demographiccharacteristics <strong>of</strong> clients recruited in Cleve-Interviewed ....... 498 ... 340 ... ...Returned <strong>for</strong> session1 .......... 411 83 224 66 P < .001Assigned toenhanced ....... 232 ... 115 ... ...Number <strong>of</strong> sessions<strong>at</strong>tendedby those assignedtoenhanced: P < .010 sessions ..... 37 16 26 23 ...1 session ...... 23 10 22 19 ...2 sessions ..... 72 74 67 58 ...1 Chi-square tests were used <strong>for</strong> all significance tests.land during the two periods. Generally, thoserecruited after the incentive changed from cash to agift certific<strong>at</strong>e were significantly more likely to befemale, younger, sex partners, less likely to be highschool gradu<strong>at</strong>es, more likely to be living in someoneelse's home and to have their children living withthem. <strong>The</strong>re were no significant differences inethnicity <strong>of</strong> the two samples (<strong>at</strong> least 85 percentAfrican American) or in the percent employed.Selected risk-rel<strong>at</strong>ed behaviors summarized in table 5indic<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> there were no significant differences inthe two groups in terms <strong>of</strong> baseline level <strong>of</strong> drug useor condom use.Overall, 48 percent <strong>of</strong> the 688 clients assigned tothe enhanced group <strong>at</strong>tended <strong>at</strong> least one session. <strong>The</strong>July-August 1994, Vol. 109, No. 4 551

Table 4. Sociodemographic characteristics, by percentages,<strong>of</strong> clients recruited in two time periods with differentincentives, Cleveland <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectTime 1(4/25/89- Time 29/19/90) (9/20-11/30/90)Characteristic cash gift certific<strong>at</strong>e Significance'Number ............ 957 211 ...Sex: Male ............. 75 65 P

drug addiction are available) than the harm caused bypeople becoming infected and spreading the virus th<strong>at</strong>leads to <strong>AIDS</strong> (<strong>for</strong> which there is not likely to beeffective vaccines or cur<strong>at</strong>ive tre<strong>at</strong>ments <strong>for</strong> manyyears).2. Concern th<strong>at</strong> because funds are limited <strong>for</strong>public health and <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention, the moneyavailable should be used only <strong>for</strong> prevention andtre<strong>at</strong>ment ef<strong>for</strong>ts. <strong>The</strong>se economic consider<strong>at</strong>ions,regarding the costs <strong>of</strong> using public health money <strong>for</strong>incentives, is an important concern, and may requirecost-benefit analyses. However, the costs <strong>of</strong> providinghealth care to <strong>AIDS</strong> p<strong>at</strong>ients, the costs to society <strong>of</strong>providing care to children orphaned by <strong>AIDS</strong> in theirfamilies, and the loss to society <strong>of</strong> the potentialproductivity <strong>of</strong> people are likely to exceed substantiallythe costs associ<strong>at</strong>ed with providing incentives to<strong>at</strong>tend intervention sessions.3. Concern th<strong>at</strong> other groups do not seem to needincentives and there<strong>for</strong>e (a) it is unfair to providethem only to some groups or (b) it is demeaning topay people to receive in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion or services th<strong>at</strong> canbe helpful to them. <strong>The</strong> belief th<strong>at</strong> some high-riskgroups may be more motiv<strong>at</strong>ed to <strong>at</strong>tend interventionsesssions without incentives does not necessarilyindic<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> it is there<strong>for</strong>e inappropri<strong>at</strong>e to useincentives <strong>for</strong> people or groups who may be lessmotiv<strong>at</strong>ed. Drug use and poverty, particularly amongmembers <strong>of</strong> inner city minority communities, mayresult in distrust <strong>of</strong> the larger mainstream society, andthus may make it very difficult to obtain adequ<strong>at</strong>elevels <strong>of</strong> particip<strong>at</strong>ion in programs. Furthermore,<strong>AIDS</strong> itself calls <strong>for</strong> a certain level <strong>of</strong> response.Although ef<strong>for</strong>ts to motiv<strong>at</strong>e or empower people toseek their own health services can be undertaken, theconsequences <strong>of</strong> HIV infection, in terms <strong>of</strong> thelikelihood <strong>of</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> diagnosis and the possibility <strong>of</strong>transmission, may indic<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> timely preventionef<strong>for</strong>ts are the priority.Further discussion and research on the advantagesand disadvantages <strong>of</strong> using incentives <strong>for</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong>prevention interventions are needed. Research toidentify methods <strong>of</strong> maximizing <strong>at</strong>tendance and toexamine altern<strong>at</strong>ive enablers or incentives is needed.In addition, research regarding such variables as thecharacteristics <strong>of</strong> subjects and the demographiccharacteristics and activities <strong>of</strong> project recruiters canbe helpful in increasing <strong>at</strong>tendance. <strong>The</strong>se issues are<strong>of</strong> urgent concern, so th<strong>at</strong> study <strong>of</strong> the efficacy <strong>of</strong>altern<strong>at</strong>ive interventions can be undertaken withrecruitment <strong>of</strong> the widest variety <strong>of</strong> persons. This willbecome even more pressing as successful interventionef<strong>for</strong>ts are found and methods <strong>of</strong> maximizing theTable 5. <strong>AIDS</strong>-rel<strong>at</strong>ed risk behaviors, by percentages, <strong>of</strong>clients recruited in two time periods with different incentives,Cleveland <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectTime 1 Time 2Money Foodorders, coupons,Behavior cash gift certific<strong>at</strong>es Significance'Injected drug use (IDUsonly):2Heroin ................. 20 18 NSCocaine ................ 27 29 NSSpeedball .............. 14 11 NSNoninjected drug use:2Alcohol ................. 42 45 NSCrack .................. 33 34 NSCocaine ................ 20 17 NSHeroin ................. 7 6 NSCondom use (percent <strong>of</strong>time used):Single sex partner ...... 18 11 NSMultiple sex partnerṡ... 26 24 NS'Chi-square tests were used <strong>for</strong> all significance tests involving c<strong>at</strong>egoricald<strong>at</strong>a; t tests were used <strong>for</strong> comparisons <strong>of</strong> means.2Mean monthly frequency.Table 6. <strong>Attendance</strong> <strong>at</strong> standard and enhanced groupsessions by incentive, Cleveland <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention projectCashGift certific<strong>at</strong>es<strong>Attendance</strong> Number Percent Number Percent Significance'Interviewed ....... 957 ... 211Assigned toenhanced ....... 553 ... 135 ... ...Number <strong>of</strong> sessions<strong>at</strong>tendedby those assignedtoenhanced: P

annual meeting <strong>of</strong> the American Public Health Associ<strong>at</strong>ion,New York, Sept. 30-Oct. 4, 1990.4. Community-based <strong>AIDS</strong> prevention among intravenous drugusers and their sexual partners. NOVA Research, Bethesda,MD, 1992.5. Stephens, R. C., Feucht, T. E., and Roman, S. W.: Effects <strong>of</strong>an intervention program on <strong>AIDS</strong>-rel<strong>at</strong>ed drug and needlebehavior among intravenous drug users. Am J Public Health81: 568-571 (1991).6. Bigelow, G. E., Stitzer, M. L., and Liebson, I. A.: <strong>The</strong> role<strong>of</strong> behavioral contingency management in drug abusetre<strong>at</strong>ment. In Behavioral intervention techniques in drugabuse tre<strong>at</strong>ment, edited by J. Grabowski, M. L. Stitzer, and J.E. Henningfield. NIDA Research Monograph No. 46.,Department <strong>of</strong> Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD,1984, pp. 36-52.7. Kadden, R. M., and Mauriello, I. J.: Enhancing particip<strong>at</strong>ionin substance abuse tre<strong>at</strong>ment using an incentive system. JSubst Abuse Tre<strong>at</strong> 8: 113-124 (1991).8. Improving p<strong>at</strong>ient compliance in tuberculosis tre<strong>at</strong>mentprograms. N<strong>at</strong>ional Center <strong>for</strong> Prevention Services, Centers<strong>for</strong> Disease Control, Atlanta, GA, revised February 1989.9. Division <strong>of</strong> Tuberculosis Control, South Carolina Department<strong>of</strong> Health and Environmental Control, and American LungAssoci<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> South Carolina: Enablers and incentives.Columbia, 1989.10. Morisky, D. E., et al.: A p<strong>at</strong>ient educ<strong>at</strong>ion program toimprove adherence r<strong>at</strong>es with antituberculosis drug regimens.Health Educ Q 17: 253-267 (1990).11. Morisky, D. E., and Malotte, C. K.: A cost-effectiveapproach to increase adherence to tuberculosis regimens.Presented <strong>at</strong> the 120th Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the AmericanPublic Health Associ<strong>at</strong>ion, Washington, DC, Nov. 10, 1992.12. Deren, S., Davis, W. R., and Tortu, S.: Who <strong>at</strong>tends <strong>AIDS</strong>risk reduction group sessions?: preliminary analyses <strong>of</strong> theimpact <strong>of</strong> client characteristics and incentives. Third Annual<strong>AIDS</strong> Demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion and Research Conference, Washington,DC, Oct. 29-31, 1991.13. Des Jarlais, D. C., Friedman, S. R., and Ward, T. P.: HIVand injecting drug users: special consider<strong>at</strong>ions. In Textbook<strong>of</strong> <strong>AIDS</strong> medicine, edited by S. Broder, T. C. Merigan, Jr.,and D. Bolognesi. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore. 1994, pp.183-191.14. Merson, M. H.: <strong>The</strong> HIV pandemic-global spread andresponse. No. PS-01-1. IXth Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Conference on<strong>AIDS</strong>, Berlin, Germany, June 6-11, 1993.OrderProcesng Code:Superintendent <strong>of</strong> Documents Subscriptions Order FormEl YES, please send me($16.75 <strong>for</strong>eign).subscriptions to PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS (HSMHA) <strong>for</strong> $13.00 each per year<strong>The</strong> total cost <strong>of</strong> my order is $ . Price includes regular domestic postage and handling and is subject to change.Cwtomees Name and AddreFor prvacy proUection, check the box below:O Do not make my name available to other mailersPlem Choose Method <strong>of</strong> Payment:O Check Payable to the Superintendent <strong>of</strong> DocumentsU VISA or MasterCard AccountZipEIZW|| | (Credit crdexpir<strong>at</strong>ion d<strong>at</strong>e)(Authorzing Sign<strong>at</strong>ure) 4.93Mail To: Superintendent <strong>of</strong> Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954554 Pubflc Health Reports