You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Nordic</strong> <strong>UNIMA</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>Denmark – Finland – Iceland – Norway – Sweden41

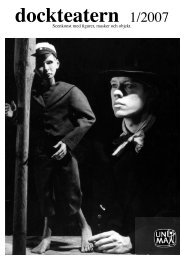

2CONTENT3. Denmark10 Finland18 Iceland21 Norway31 SwedenCover: Katma productions, Vidunderkammenphoto/puppet: Jon MihleBackcover: Mediet og Masken, Svend E.Kristensen.editor<strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway andSweden are proud to present the art of puppetryfrom the <strong>Nordic</strong> countries. There are enormousvariations within each country, but still when wepuzzle the information together, we turn out to bequite similar after all. It has been like that even whenwe look all the way back to the middle ages and thepuppetry organized by the Catholic Church. Wehave a common history. In the nineteenth centurywe had the travelling showmen touring throughparts of Norway, Sweden and south Finland, oftencontinuing to St Petersburg, and then comingdon the east coast of the Baltic. We also hadlocal puppeteers picking up the craft from thesetravelling showmen, and we had fine artist andauthors who set out as puppet theatre amateurs.The 1950ies we had our pioneers of the puppettheatre for children. In the 1980ies puppetry wasaccepted as a special branch of theatre art. Butnow, in the first decade of the new century wediscover that our isolation in our corner of the artof theatre is broken down. Puppetry is now to befound everywhere – in the actor’s theatre and infilm and television as well in concerts and touristplaces and computer games.This magazine reflects what is going on in the<strong>Nordic</strong> puppetry just now. Only a few of membersof the <strong>Nordic</strong> <strong>UNIMA</strong> centres could travel all theway to <strong>UNIMA</strong> Congress in Australia. But by thismagazine we want to greet the delegates and ourcolleges at the Congress and thank you for keepingup the worldwide work for puppetry.Dr. art. Anne Helgesen - editor<strong>Nordic</strong> <strong>UNIMA</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>Denmark – Finland – IcelandNorway – Swedenediton 1 2008 of the magazine Ånd i hanske. ISSN 0800-2479<strong>UNIMA</strong> FinlandThe office and library of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Finland is situated in puppet theatre AkseliKlonk, Oulu.Board 2007-2008: Janne Kuustie, president, Oulu, Mr Hannu Räisä, treasurer,Hämeenlinna, Mrs. Marja Susi, Turku, Ms Ilona Lehtoranta, JyväskyläMr Timo Väntsi, Turku, secretary: kati-Aurora Kuuskoski, Ouluemail: unimafinland@yahoo.comhomepages: www.unima.fi <strong>UNIMA</strong> SverigeNational president: Helena Nilsson (artistic manager at Marionetteatern iStockholm)<strong>UNIMA</strong> Sveriges postadress: Box 161 98, SE - 103 24 Stockholm, Swedene-mail: info@unima.seURL: www.unima.seEditor of the magazine Dockteatern: Tomas Allldahl<strong>UNIMA</strong> NorgeNational president: Svein GundersenBoard: Einar Dahl, Arvid Ones, Nina Engelund, Marthe Brandt, MarianneEdvardsenEditor of magazine Ånd i hanske: Anne HelgesenPostadress: <strong>UNIMA</strong> Norge, Hovinveien 1, 0576 Osloemail: post@unima.nohomepage: www.unima.no<strong>UNIMA</strong> DanmarkNational president: Hans Hartvich-Madsen, Board: Martin Elung, Ida Hamre,William Frohn, Peter Jankovic, Janne KjærsgaardEditor of News Letter: Astrid Kjær JensenPostadress: c/o Thy Teater, Handværker Torv 1, 7700 Thistedemail: thy@thyteater.dk<strong>UNIMA</strong> IcelandNational president: Sigridur Sunna Roynisdottir Board: Helga Arnalds, Maria B.Steinarsdottir, Bernt Ogrodnik, Katrin TorvaldsdottirPostadress: <strong>UNIMA</strong> á Islandi, Njörvasund 14, 104 Reykjavikemail: stjornin@unima.ishomepag: www.unima.is<strong>Nordic</strong> <strong>UNIMA</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>Chief editor: Anne Helgesen – NorwayLayout: Jon Mihle – NorwayThis is also editon 1 2008 of the magazine Ånd i hanske.ISSN 0800-2479Distributed by <strong>UNIMA</strong> Norway, Hovinveien 1, 0576 Oslo,NorwayThe magazine is sponsored by Kulturkontakt Norand Arts Council NorwayDenmark - national editorSvend E. Kristensen, Performer in his own company Mediet & Maskenmedietogmasken@mail.dkFinland - national editorsTimo Väntsi, Regional artist/ puppet theatreRegional Arts Council of South-West Finlandtimo.vantsi@minedu.fiAnna Ivanova, Specialisation Manager of the departement of thepuppet theatreTurku Arts Academyanna-ivanova@turkuamk.fiIceland - national editorHelga Arnalds, Puppet artist in her own company The 10 finger theatre.hekla@mmedia.isNorway - national editordr. art. Anne Helgesen, artistisc manager of The PuppettheaterEnsemble of the Catannehelg@online.noSweden - national editorsTomas Alldahl, editor of the Swedish <strong>Magazine</strong> Dockteaternred@unima.seThis magazine is sponsored by:

Report from<strong>UNIMA</strong>Denmark 2008:The Chairman’sIntroduction.In the present article I will deal with a formalaspect of the Association of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark’sdevelopment. <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark has acquired anew set of statutes.There are two reasons for this.Firstly, in recent years, members of our associationhave undertaken several interesting large scale, outgoingactivities. This is a positive thing and a big stepforward for <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark. However, it was aproblem that we lacked a set of statutes suitable formanaging large financial budgets, so activities of thiskind could be implemented without risk to the boardmembers. According to Danish legislation, individualscan be held personally responsible in the absenceof a clause in the statutes stating that the board onlyhas to answer for an amount equivalent to the totalholdings of the association itself, and this clausewas absent in the old statutes. The new statutes takemeasures to resolve such economic situations, and,while no one hopes that these activities will create adeficit, it is nevertheless important that board membersworking on a voluntary and non-salary basisare not suddenly held responsible for debts resultingfrom the activities of the association.Secondly, the old statutes were not designed to handlethe association’s many different types of activities.From a theatre related point of view, the name<strong>UNIMA</strong> is rather unique, in that the word ”theatre”is not a part of the name. In every other theatreorganization you will find the word ”theatre”. Thisis an interesting detail that contains the seed to why<strong>UNIMA</strong> is significantly different from other organizations.It is the diversity of approaches to the puppetor the marionette, and not just the ”puppet in play”that constitutes the central turning point of the association.<strong>UNIMA</strong> deals with a host of different subjectareas, which is reflected partly in the number of commissions.Even though there is a wish to limit thisnumber, it is interesting to note that just the oppositehas taken place. This proves our belief in the possibleuse of the puppet in innumerable contexts.In Denmark many of the <strong>UNIMA</strong> commissions’ areasof activity are also represented. This is one of the reasonswhy I wanted to turn the Danish structure towardsa more contemporary management style. Because nosingle person can be a specialist in all of the areas thatthe members of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark operate in. In manycontexts we are dealing with deeply serious and specificprofessional fields at very advanced levels of educationand experience. Once again, the old statutes gotin the way. Today, with the new statutes, it is possibleto achieve a good distribution of the tasks and responsibilitiesof work on the board. Propositions, of course,still need to be amended at board meetings in order tobe carried, but hereafter it is possible to continue thework within the agreed framework.Let me mention that the first evident result of thesestructural changes is an increase in the number ofboard members, a consequence of which has been anexpansion of the statute designated number of seatson the board. The fact that the new board membershave indeed increased the diversity and the number ofapproaches is a great advantage.<strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark has gone through an exciting andinteresting development over the past twenty-fiveyears. This development is still continuing. At presentwith several new areas of work. I have good reason tobe optimistic about <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark’s developmentin years to come.Artistic Director and Stage DirectorHans Hartwich-MadsenChairman of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark3

With a look over theshoulder4Svend E. Kristensen <strong>UNIMA</strong> DKAs editor for the Danish part of the collaborative<strong>Nordic</strong> <strong>UNIMA</strong> magazine I will here give a slightpresentation of some of the activities which is goingon in Denmark for the time being.A new puppetfestival was forming in Copenhagen in2007 with great success. The Festival had a smallerevent February 2008 called “Focus on Puppet Theater”,which like the first real event again was totally soldout. It is possible to visit the festival which will kick ofagain in spring 2009 at www.puppetfestival.dk.2007 was also the year were the international “Festivalof Wonders” in Silkeborg were lining up for a greatsupply of shows and workshops for the 6’th time.Beware next festival will take place in November 12- 15, 2009.In the meanwhile the element of animationtheatrein Denmark has for the past years had a surprisingimpact on the other stageart activities. Suddenly youfound puppets in various performance plays and eventsoutside the normal range of <strong>UNIMA</strong> members.A spectacular solo performer Anders Christiansen andhis Stilleben used 2005 to handle 3 flappy life-sizedpuppets in his play “Unrest/Lack”, while he himselfwas partly a puppet to. This play did cast surprisinglynew light on the scene of puppetry.Puppet- andanimationtheatre inDenmark 2008...was supported by the Danish artcouncil.In 2009 even another Danish situated performancetroupe called Norpol under the guidance of DanielNorback, will explorer the use of puppets in theperformance Black Out.Here I shall also shortly mention a project in theeducational field lead by graduate from Theatricalscience in University of Copenhagen Marie-Vibe. Theproject is focusing on the use of masks and puppets whenmaking theatrical plays with so called psychologicalvulnerable students at Daghøjskolen Sind. The schoolends with a staging in August 2008, at a world congressfor psychiatrists in Aalborg.Other puppet and animation activities will be describedmore thoroughly in the passages to follow which isa conglomerate with omissions of the lampoon of<strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark for the world congress 2008.The puppets also found their ways into a new group thatwas forming around theatre and animation situated inPlan B in Copenhagen 2006-2008 with the puppetmakerCarl Press in activity.Katrine Karlsen is to be mentioned for herwork in “Grænseløs” (borderless), which is workingin the mixture between installation, performance andpuppetry and is mainly doing shows for youngsters andtheir adults.Sofie Krog TeaterFreestyle Puppet Acting &Poem Bizarre wrapped in aJack-in-the-box-comedy.Bådteatret in one of the canals of Copenhagen didchoose to have a hole season of research devoted toanimationtheatre 2006. They staged thus for adultsboth grotesque, subversive and ritualistic performancesdown in the deep black stomach of the boat. Onewas puppetmaker and player Rolf Søborg Hansen incollaboration with director Emil Hansen “Women isthe nigger of the world” a former radiodrama. Anotherwas Mediet og Masken in collaboration with directorRolf Heim with “The burial wedding”, where thedevelopment of the special life-size animationfigureArtis tic profile:Sofie Krog’s passionate relationship with animationtheatre started with a spicy love affair with the puppetSenor Gomez, who seduced her into the magicalworld of puppet theatre. With an exquisite sense of theimportant detail Sofie Krog creates her own puppetswith huge panoply of physical movement from rotatingeyes to movable eyebrows, wiggling ears and more.The ’Sofie Krog Teater’ broke through on theinternational stage with the award winning show’Diva’ in which she creates true theatre magic on seven

small stages while hiding in the depths of a red velourrotunda. Sofie Krog is the driving force of the companyin which she conceives the ideas, builds the puppetsand stage props and do the playing.The performances grow out of a fresh, unconventionaland creative energy in which anything is possible. Withthe nutty combination of freestyle puppet theatre andbizarre poetry, the performances surprise over and overbeing liberating unschooled and crazy.Current production:’DIVA’In the depths of a dark and quirky cabaret the lives ofa beautiful diva, her lovesick butler, a mischievouslab assistant and a beyond-mad scientist are about tocollide. Audience members are lured into the mysterywithin the cabarets walls as each character endures anill-fated night that may well be their last. ’DIVA’ is atour de force of mutual dexterity. Sofie Krog is workingon a new performance ’THE HOUSE’ in collaborationwith Davis Farco De Grado which will be presented inthe spring of 2009.Artistic director Sofie KrogMember of <strong>UNIMA</strong> DKTelephone: +34 680 950 360E-mail: diva@sofiekrog.comwww.sofiekrog.comTeater RefleksionDenmark’s most establishedprofessional animationtheatre.’Teater Refleksion’ aims to initiate the audienceand professional actors into the art and the magic ofanimation theatre.The theatre uses very different techniques and typesof performances. They use different types of puppets,abstract or concrete objects, visible or concealed actingwith puppets, pure puppetry or dialogue betweenpuppet and puppeteer.Generally the puppets or objects are given humancharacteristics with which the audience easily canidentify themselves. The puppets are created with anopen expression, giving the possibility to express manydifferent moods and thought. In this way they get asymbolic value which has a universal validity.The theatre is known to aim uncompro-misingly atquality and absorption. Their performances are knownto tie content and expression into a unified estheticalwhole, talking to senses and intellect as well aschallenging our fantasy with dreams, hopes and fears.They create little openings into a more mystic dimensionin life by intentionally using intervals and silence inthe perfor-mances and thus giving the audience time tothink and feel for themselves.’Teater Refleksion’ has a wide network consisting ofDanish and foreign theatres, actors, authors, musicians,puppeteers, puppet- and animation theatre schools andfestivals with whom they collaborate on performancesand guest performances.The theatre has held a number of courses for professionalactors, nursery teachers and school teachers as well asfor other interested persons. These activities as wellas performances have highly influenced spreading theknowledge of animation theatre in Denmark.Theatre director Bjarne SandborgMember of the board of <strong>UNIMA</strong> DK from 1998-2004Telephone: +45 86240572Fax: +45 86240593E-mail: refleksion@refleksion.dkwww.refleksion.dkTeatret LampeChildren’s Theatre withpoetry, humour andattitude.With an alluring combination of acting, puppetry, livemusic and visual art, Teatret Lampe has specializedin creating humorous, poetic and topical shows forchildren. In addition to modern interpretations ofclassic fairy tales, Teatret Lampe also produces thoughtprovokingcontemporary Danish drama.At Teatret Lampe, over the past years, we have workedincreasingly with puppets in our productions foryounger children. One of the many reasons for thisis our fascination of the innumerable possibilities ofexpression (”Puppets can do more than humans”, weusually say) combined with a great interest in workingtogether with professional visual artists to develop newideas and forms in Puppet and Animation Theatre.In our theatre we use actors as puppeteers – and viceversa! It’s hard to say who comes first. In the beginningthere was the actor, the human, the body dancing andnarrating. But before long the human, the actor beganto play with tools and animate them. Or was it the otherway around? Whichever way you chose to look at it,5

acting with puppets, to me, represents a movementaway from the body – a magical journey of the soulfrom my self to the puppet.Wargo Brekling”The Girl Who Went Away” for ages 7-11 years,directed by Nikoline Werdelin6But who is this mysterious self, had it not been for me,the actor and puppeteer always present, there in thebackground? In other words an interaction. The puppetand I. Me in the puppet. Me as the puppet. Or as partof it.As actors we strive (with the director) to channel ourentire range of bodily and emotional energy into thepuppets on the puppets’ own premises and to find thebalances between being in focus oneself and beinganonymous puppeteers. This demands a great deal ofrespect and humility towards the puppet – a disciplinethey do not teach at the Danish Acting Schools. Yetthe moment the actors make room for this process (theconfrontation with your stage ego) the leap (apart fromthe puppet technique, which is a different story, and fartoo long for this article) is not alarmingly big. We thinkand feel with our puppets, just like when we transformour own bodies and minds to play a new part.So the actors intervene and become a part of thepuppet’s personality. Vi give ourselves to the puppetand it must learn to deal with it. Sometimes it’s a battle– sometimes it’s as easy as pie. I must constantly submitmyself to the puppet’s basic physique and expression,its dramaturgical function, but the puppet must obeyme, too. After all, it cannot live without my skills as anactor (mental energy) and puppeteer (physical energy).In return, as a co-actor the puppet repeatedly gives meunexpected inspiration and surprises. The very secondI think that I’ve got it figured out, the puppet invents acompletely new movement, flies about like a helicopteror flattens out like a cloth. In our magical symbiosiswe do the impossible together. The puppet becomes anactor. I disappear into the puppet for a time. With thefull power of my imagination. Because that is the onlyway that the story, the words can become imbued withlife and meaning. And allow a new puppet show to seethe light of day. On opening night we’re ready – actorsand puppets. And lo and behold – it happens anew! Theaudiences are moved. They applaud, they smile, they’rehappy. And thoughtful.Teatret Lampe’s current puppet and animationproductions”The Ugly Duckling” for ages 2-5 years, directed byGitta Malling”Wish!” for ages 2-6 years, directed by KamillaTeatret LampeNørrebrogade 5C, 2.salDK 2200 CopenhagenPhone: +45 35 36 19 47fax: +45 35 36 10 04mail@teatret-lampe.dkwww.teatret-lampe.dkNørregaards TeaterThis theatre combinesacting with animation,singing and music in theirperformances.An animation performance is created’The camel came last’ is the title of a children’s bookby Jesper Wung-Sung. We were inspired by the bookand used it as starting point for our latest performancefor children from 3-8 years and their parents. It will bepresented at the yearly festival for children’s theatre inNæstved 2008.The book is full of wonderful illustrations by UrsulaSeeberg. We talked to Jesper Wung-Sung and made anagreement with him about dramatizing the book. Themain character is God and since he is the only one wedecided to make it a one-person-play. We made a teamconsisting of Heine Ankerdal as actor, Katrine Sekjæras dramaturgist, Claus Helbo as scenographer and HansNørregaard as director.We all had a good deal of demands which were putforward. We decided to reuse an old scenographyand hereby we discovered, that it could be used in adifferent way. We wanted to follow the book, but withas few words as possible. We wanted only one puppetand as the other main character was the camel, it wasclear that it had to be a marionette. One of the demandswere that it the marionette should be lying on stage inpieces in order to be assembled by God at a certainpoint during the play and it was very important that itwas movable.Michael Vogel (Germany) from ’Figurentheater Wildeund Vogel’ with whom we have worked before madethe camel. He constructed it like two marionettes. Onecross steered the head and the other cross steered thebody and the legs, and it could all be put together withstrong magnets. It was hard work getting accustomedto the camel. There were many strings to keep track ofand when the camel was lying on the floor representingthe leftovers God had discarded, the strings would veryeasily get tangled. And the magnets would catch eachother and everything would look like chaos. And thenGod would have untangled everything once again.As the title says the camel turns up rather late in the

play so the rest of the performance is about all thethings God created in the first six days.We chose to work with the idea of simplicity – thesimpler the better and after many test performanceswith an audience we were certain that it was the rightway to go. We also chose to take playing in foreigncountries into consideration and thus the prologueand the epilogue are pronounced by a little girl whichsurely can be done in many other languages. Theperformance itself has very few words and is easilycomprehensible.Artistic leader and director: Hans NørregaardMember of the Board of <strong>UNIMA</strong> DK from 1999-2003Telephone +45 86344285Fax +45 86344297E-mail: post@nrt.dkwww.nrt.dkStageart Theatre“Mediet og Masken”Ritualistic orientatedperformances for adultswith hypernaturalistic lifesizedanimation figures.Mediet og Masken (The media and the Mask) isfounded by multiartist Svend E Kristensen.I term my performances neo-puppetry, thus I try toreinvent the use of puppets in a modern setting foradults. It is not only the setting I thus try to enhance,but also the search for new variations in the terms ofmaterial and design for the use in animationfigures.The last animationfigure and sculpture is a full scalebody made by carbonfibers, silicon, specialrubberand kevlar. It is hybermobil and it takes a lot of effortto manipulate, thus it also have a lot of possibilitiesconverging towards modern artobjects used in acrossover in performance events and plays.“Mediet og Masken” normally uses a richbackground of mythological understandings and evenesoteric material in order to restage rituals for a modernpublic. You will also find allusions to a media critic insome of the plays. Here the artist/researcher will askwhich media are leaving the most space for animationand fantasy done by the audiences themselves.Svend E Kristensen also do lectures about puppetryin concordance with mythology, modern aesthetics,media- typology etc.Stagings:Revenge of the Crystal, solo.Begravelses Brylluppet (The Burial Wedding).Feralia Nuptia the solo, Tokyo Japan.Upcoming: The blind, solo. Tokyo Japan.Mediet og MaskenSvend E Kristensenwww.medietogmasken.dkinfo@medietogmasken.dkPuppets in “TheRound Tower”ExhibitionCopenhagen 2008About two years ago a couple of board members of<strong>UNIMA</strong> decided to apply to ’The Round Tower’ forpermission to hold an exhibition on Danish puppetryfrom October 4th till November 16th 2008. Themanagement of ’The Round Tower’ was delighted togrant the permission especially since they were lookingfor activities which involved children. They expectaround 50.000 people to visit the exhibition during thisperiod.’The Round Tower’ is a landmark in Copen-hagen andit was built on the initiative of King Christian IV (1588-1648). In 1987 the hall was reopened after thoroughrestoration and the almost 900 m2 of the room is nowone of the most beautiful exhibition halls in Copenhagen.When we got the approval we started out contactingall the puppeteers and puppet theatres in the countrybecause the idea is to unite all the puppets we canpossible find in this exhibition. The response has beenhuge and right now we have almost 50 theatres, puppetmakers and players who have accepted our invitation.During the exhibition period there will be puppetshows, puppeteers telling stories about their plays orpuppets or stories from their life with puppets and therewill be workshops for children as well as for adults.The setting has not yet been decided, but the idea is notto use the scenography the puppets originally were inbut to give them a totally new setting and we hope thiswill be possible. All in all we count on having between300 and 500 puppets summoned to The Round Tower.And one thing is for sure; puppets, puppeteers andvisitors are all going to have a great time.Lilo SkaarupMember of International Council of <strong>UNIMA</strong> 2004-20087

8Stage ArtDevelopment CentreOdsherred TheatreSchoolProfileThe Stage Art Development Centre, OdsherredTheatre School is subsidized by the Danish Ministryof Culture. The primary task is to offer developmentand education to all groups of professional performingartists and dancers – with a special focus on theprofessional theatre for children and young people.Puppet and animationThe school has during the last 10 years offered awide range of courses and workshops with the finestinternational artist and teachers from the puppet andanimation theatre field. Odsherred Theatre School arenow planning an art diploma and bachelor educationin puppet- and animation theatre.Post education in generalAt the moment O.T.S. has about 100 courses andworkshops each year and all the activities contain avarious group of actors, directors, writers, dancers,theatre theorists and other theatre people.Theatre in SocietyIn our Centre of Knowledge and Competence we wantto unite the theatrical practice and the theatretheory.We have started this task already by being a partof a PhD project together with The Universityof Copenhagen and The Danish University ofEducation. One of our tasks is to develop a diplomadegree concerning Performing Arts in Society. Theeducation is based on the wish to strengthen theactor’s theatrical work in progress and in process indifferent parts of society: With children and youngpeople and with leaders, doctors or teachers. Theatreis seen as a tool that makes new processes and newrelations possible.An open invitation….Odsherred Theatre School is situated in the beautifulWest Zealand, the biggest of the islands in Denmark.Within the school there are three rehearsing stages,one professional black box scene, 15 doubles roomsand 10 single rooms, meeting space, computer accessand a lot of good atmosphere and the village NykøbingSjælland is only 2 km. away. So, if you would like todevelop your project in creative surroundings or wantto indulge in performing processes for a while, do nothesitate to call and ask us for possibilities.Director Martin ElungVice chairman of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark<strong>UNIMA</strong> Councillor for 2008-2012Phone: +45 59931009Mail: martin@otcenter.dkThe Animation Linein ThistedI have the joy of teaching students at the SocialEducator Training Centre in Thisted. From 2004 to2007 we had a special Animation Line. The students onthe Animation Line were to contribute to fulfilling theaims of the Social Educator training programme. Apartfrom this, the aim was for the students to acquire:-Experience with Animation Theatre, both of their ownwork and the work of others.-Knowledge of and insight into the fundamentalconcepts and methods of arts and handicrafts relatedfields of activity, in relation to the animation processesrelevant to social educational work.-Aesthetic insight and the ability to create animationfigures, Animation Theatre and related areas.-Competence in analysing and evaluating AnimationTheatre and entering into discussions about it.-Experiences with applying competence in and insightinto Animation Theatre in social educational work.The visions of the Animation Line were:To supply social educators with subject-specificknowledge, in order to qualify their social educationalwork.That Animation Theatre and the process of animationis explored and challenged, so that also the socialeducational potential is examined.That Animation Theatre is applied more in ourinstitutions and in our social educational work.That the artistic knowledge of Animation Theatre willgrow and prove productive.To acquire a number competent students with artisticskills, knowledge, and the power to use it in their socialeducational work.Aud Berggraf Sæbø from Norway describes the valuesthe animation figure can have for social educators:The social educator can involve the emotional sidesof the child in a learning process, and stimulate thechild emotionally. The figure can evoke concentration,and create a distance to problems and conflicts ofthe child. It can stimulate the progress of languageand can help children understand different subjects.Berggraf categorises the animation figure in the fieldof education. She also believes that it can help thechild to express feelings, expand their imagination andcreativity, create opportunities for self-understanding,and gain an understanding of their surroundings.The animation figure can be seen as a tool for learning.But it is important also to be aware of the qualitiesthe animation figure creates via the potential space.Winnicot describes the potential space shaped by theouter and inner life. This rest- and development zone canseparate and connect the outer and inner reality, whichis important for children’s ability to create symbols,and for their skills of distinguishing between illusionand reality. This zone is a foundation for artificial andreligious experiences and for expanding creativity.To fill this zone, it is necessary to have desirable

conventional phenomena and objects, because they canfunction as connecting links.Anne M. Helgesen, Dr. Art. from Norway, classifiesthe animation figure into four fields: The religious, thepopular, the educational, and the artificial field. Wemay explore the animation figure as an educationaltool, but to be a qualified social educator from theAnimation Line, you have to know all four fields. IdaHamre describes animation as cross-aesthetic art form.That demands skills from the students of the AnimationLine.In 2007, the students took their final exam. Each grouphad to perform their Animation Theatre play, to presenttheories related to their play, and to be well-foundedin their didactic reflections. The students have theirbasic knowledge of theory from the work of dr. IdaHamre, and they also make references to Aud Berggraf,Konstanza Lorenz, Margrethe Helgesen etc.One of the groups worked with the animation figure inpoetic theatre. They showed a poetic performance abouta man and his struggle with the Devil. They defined poetictheatre as sensuous and impressive. They experimentedwith the unique qualities of shadow figures combinedwith other figure types. Another group worked with thechallenge of making different animation figures goodstorytellers too. They performed a play, with a marotfigure,telling the story about Magda, an old lady, whofalls asleep and whose knitting turns into an animationfigure that tells its own story. Finally Magda wakesup, and the marot figure ends the story. A third groupperformed a play about a very shy boy and how he getsa girlfriend. Their animation figures stood on a table,and were to some extent static, so they worked withtelling and showing the play, creating inner pictures forthe audience. The fourth group used shadow theatreand performed a play telling the legend of wise womenmaking peace. They combined shadow theatre withother figure types in their work to develop contact withthe audience. The last performance was made by onestudent. She conjured up small finger figures from herbig, old suitcase, telling the story of a princess searchingfor a friend. Her aim was to make all the figures seemconvincing. This was solved by an awareness of thedramaturgic choices, especially voices and sounds.9The external examiner noted in her report that theAnimation Line was at the highest professionallevel, and that it was obvious that the students hadexperienced an intense termination, with a high level ofconcentrated and inspiring training. At the exams it wasobvious that the students had achieved an artistic senseof Animation Theatre, and now, after having startedtheir work as social educators, it is evident that theyhave the ability to use their special skills in their socialeducational work.Hanne KuskAssociated Professor at VIA University College in DenmarkBoard Member of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Denmark

:by Anna Ivanova-BrashinskayaGlobal WarmingBy Anna Ivanova-Brashinskaya101My «Finnish career» in education began in theearly days of the XXI century when I was invitedto Turku, the fifth largest city in Finland, to lectureon the history of puppet theatre. In all honesty, I havenot even begun to imagine that in Finland, let alone,provincial Finland, there was a puppetry education atall. I guessed that, as all nations whose history is notvery long, the Finns had courses for semi-professionalactors who, in the stiffly-competitive climate, strivedto broaden their skills – even if by venturing into theneighbouring media, such as puppetry. I was wrong asone could be. It turned out I had to teach an intensive 40-hour-long course on the history of just glove (!) puppet,as the students were preparing to start manufacturingPetrushkas. In the St.Petersburg Academy of theDramatic Arts where I was a Puppetry DepartmentChair and history professor at the time instructorscould not afford such a luxury of overlapping practicewith theory. As is usually the case with puppet theoryin general, they went their own, «theoretical» way,coinciding with the practical reality only by way ofaccidents.I faced the Finnish students at the close of their secondyear and they have not heard a word of puppet historyyet. Since I could not be sure that they would in thefuture, I asked, at the end of the «glove» course, ifthey had any questions on other topics. And so, ourconversation drifted towards the Russian puppeteducationmodel.I spoke about Mikhail Korolev, a legendary directorwho, in the St.Petersburg Academy (The LeningradState Institute of Theatre, Music and Film, or LGITMiK,then) had built a puppetry school where puppeteers weretaught long and with narrow specialisation in directing,acting, design, or construction. The future professionalsthere collaborated on various productions that werelater performed in the College Theatre (and weretremendously popular among the general audiences).Upon graduation, the Korolev students would part theirways, go to different cities where they would createnew theatres, while continuing to collaborate throughfestivals, workshops, etc., thus forming a wide circle offriends, supported by critics and audiences alike. TheKorolev school served as a model for other puppetryschools – there are four of them in Russia now. I heardmyself speak in that auditorium and it sounded like Iwas telling a beautiful fairy tale in which a magicianhad built a golden castle overnight. Of course, this wasnot entirely true.2The Korolev puppet school was not the first inEurope (the Prague puppetry department wasestablished in 1952, 7 years prior to the firstclass in Leningrad). In mid-XX century, puppet theatrehad strong aspirations to become, in its modernity,an alternative to the modern art, so there were plentyof courses, seminars and workshops everywhere thatwere awaiting nothing so much as to be centralized andassimilated by the higher education. The movementwent on well into the 1980s: new schools were openedin Berlin (1971), Wroclaw (1972), Bialystok (1975),Minsk (1975), Stuttgart (1983), Charleville-Mezieresand Buenos-Aires (both 1987).The emergence of the specialized puppetry schools wasoften related to the rise of the state puppet theatres inneed of trained specialists of all profiles. No wondernew schools were formed in the places where a strongpuppetry tradition survived through the ages.Thus, in the Soviet Union alone there were over 200state puppet theatres, open to all those new professionalswho could muster more than one puppet technique.The Soviet puppetry schools were in effect servicingthe actual theatrical process, while guaranteeingemployment to their graduates. The Korolev modelturned out to be so strong to have survived the collapseof the state and the whole social system specificallythanks to the strength of the Russian puppetry tradition.It never seizes to amaze foreigners: what the reputationof puppet theatre in Russia must be if the prospectivepuppeteers’ entrance competition is so tough, thelength of the education is 5 years and employment isguaranteed! How improbable this picture may lookoutside of the sheltered Russian system I realized onlyabroad.

3The population of Finland is a just over 5 mln.– nearly as big as that of St.Petersburg. Untilrecently, there were 4 puppet theatres under thebill for theatres and orchestras enjoying on the top oftheir self-generated income permanent governmentand local council subsidies. Since the oldest of them,Vihreä Omena (The Green Apple), closed in Helsinkiin 2004, there are three: Mukamas in Tampere, Sampoin Helsinki and Hevosenkenkä in Espoo, the fastgrowing city in the capital region. Each employs fiveto ten people. Aside from the state theatres, a numberof small independent companies of various degreesof quality and professionalism are striving to survive,depending mostly on small grants from public funds(both government and local) and private foundations.Finland in this regard does not stand alone: puppeteersthroughout the European North share the same livingconditions. Almost untouched by the volcanic changesof the mid-past-century, the professional puppettheatres in all these countries (Sweden, Norway,Denmark, and Iceland) put together can still be countedalmost on the fingers of two hands. Not to mention thespecialized education: it ended never really havingbegun. In the Norway Drama Academy (Fredrikstad), abrief tryst with the puppetry was soon replaced by themore fashionable “physical theatre”; in the StockholmDramatiska Institut irregular puppetry courses stoppedin the early years of this century; Iceland and Denmarkhave never known a regular puppetry education at all.In the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) thesituation is similar. So the Puppet Theatre Departmentestablished in the Turku Arts Academy in 1999 turnedout to be the only one in the huge North-Europeanregion, which is so greatly developed in many othercultural ways.4Does all this mean that the North of Europe is thepuppetry’s «tabula rasa», the snowy blank spoton the map of puppet theatre? Yes, but only ifby «tabula rasa» one means not the emptiness, but thepromise of future filling. And the quality of this fillingdepends almost entirely on what the puppet educationis prepared to offer to the theatre world.Indeed, the problem of students’ future employmentmust concern a school and influence its educationalconcept. A student must graduate prepared to competenot only in the world of contemporary theatre, alreadysetand not always friendly to newcomers, but also withhis/her classmates who are gearing for the same. At thesame time, a potential to create a new theatrical structurefor the region which is quite open to that is no lessimportant for today’s graduates than competitiveness.In effect, it means that a student must be educated mostbroadly and fully in all the aspects of the craft, and atthe same time present a highly defined individuality.The first thing most of the prospective students arewilling to admit at the entrance exams is that they havenever been to a puppet theatre. The teacher’s task, while,perhaps, smiling inwardly, is to realize this innocencenot as a shortcoming, but as a virtue of a future student.He/she does not know yet what puppet theatre is andmust be, how it «may», or «may not» be done. Thisstudent is also a «tabula rasa» offered to the teacher tobe filled out with a maximum spectrum of possibilities.The student’s task, then, is, having orientated him/herself in the diversity of the types and techniques, findhis/her own private personal puppet theatre.What this really means is a reformulation of theprofession of the educator (or, Master, as they arecommonly called in Russian schools). The Master asa keeper of a certain tradition, of a specific aestheticsthat he is called upon to transfer onto his students,becomes unnecessary, even harmful under the «tabularasa» circumstances. Today, instead of teaching thestudent a certain specific system of theatre, the teachermust program the process so that in the group aspectit would develop «horizontally», wide, and in theindividual aspect, «vertically», deep into the craft. Thiscalls for a replacement of a «teacher» with a kind of a«programmer», who is fluent in all the languages thatthe medium can speak in and strives to program thestudents so that they are broadly informed and narrowlyspecialized at the same time.Considering how to meet such demands, we at the PuppetTheatre Department in Turku came to the conclusionthat a thought-through system of master classes andworkshops with the lead practitioners of the craft fromall over the world would work best. The invited foreign«guest-stars» would conduct an intense introductioninto a narrow specialization (marionettes, glove, paper,or shadow theatre, object and texture theatre, masks,etc.), while the staff teachers would adopt the role oftutors, developing the condensed knowledge of themaster class into a broader picture and fitting it to eachstudent’s individual needs and abilities.The key to this «tutoring» job would be to protect astudent from any kind of «final knowledge», any kindof assumption or preconception of what the puppetand puppet theatre actually are. Each project requiresan invention of a new language, a new puppet theatredetermined by the material. A rejection of teaching acertain method becomes a method in itself, a method inwhich a shift is taken from technology to the substanceof the art form as it exists today.5All the changes that have been happening inEurope in the recent past seem to be pointing in thesame direction. Thus, the formation of EU causeda unified system of curricula and credit certification(ECTS - European Credit Transfer System). Specialfunds were created specifically to support the studentand teacher exchange programs (the most popular ofwhich is Socrates-Erasmus). The system of studentfestivals has developed greatly. Regular puppet schoolfestivals, such as those in Bialystok, Wroclaw, andCharleville-Mezieres, partly financed by the sameEuropean educational programs, have become arguablymore popular among producers and professionals thanthose of professional theatres. Student productions thatby definition must possess pedagogical rather thanartistic merit have often turned out to be more modernand inventive than the «well-made» professional11

12shows which (not to mention the price) makes themmuch more attractive to the prospective buyers ofthe theatrical product. (This, in turn, turns a collegeeducator into a producer as well). Furthermore, theschool festivals have begun to shift from showcasingthe already-completed student works that may be tooheavily influenced by the teachers towards the conceptof special workshops, or labs, in which the studentsmust create an experimental project in the course of thefestival (usually, 7 to 10 days).6So, all would be well, if not for one little glitch.There are simply no places to go for someonewho would want to learn the art of puppetry in theNorth of Europe today. They could go to Charlevillein the hope of getting into this most prestigious ofall schools; or take a brief post-graduate course atthe London Speech and Drama School; or receive analternative (pantomime or drama) education, planningto later adapt it to puppetry; or go for the most trustedand ancient way of «running away with the circus»- join a professional company as apprentices and gettheir skills firsthand. But none of them could go to aScandinavian puppetry school – for the simplest ofreasons: it does not exist.So, a natural thought came to us at the Puppet TheatreDepartment of the Turku Arts Academy: to joinforces and centralize our efforts by creating a unifiedScandinavian puppetry school on the basis of ourdepartment – the only existing school in the region.The first experiment in that direction has already takenplace when, in 2007, a first international Finnish-Estonian puppetry class was selected – in collaborationwith the Eesti Riiklik Nukuteater (the Estonian StatePuppet Theatre) in Tallinn. The international nature ofthe class as well as the ongoing professional exchangebetween Turku and Tallinn have substantially influencedthe educational process, widening the world – in thesense of opportunities, as well as geography – for thestudents. Six of the current students in Turku alreadyhave contracts with the Tallinn theatre and will join itfollowing their graduation.Developing this first and yet-singular experimentinto a common practice, we envision a very excitingeducational model in which an international class ofstudents from Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Norway,Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland, among possibleother countries, would be taken in every other year inTurku. Educators from the respective countries wouldbe responsible for sustaining those countries’ culturaltraditions, while the cosmopolitan nature of the classand education (which is already conducted in English)would certify the breadth of the students’ outlook. (It isworth mentioning that there are no real administrativecul-de-sacs for this model, as EU citizens have a rightfor a free education in Finland).7As this model would fall under the requirementsof our Department, as we are trying to build ittoday, here, finally, are some of the particulars ofwho we are and how we teach in Turku. The PuppetTheatre Department was formed within the PerformingArts Department of the Turku Arts Academy in 1999.In 2003, 2005 and 2007 the first three classes havegraduated and it must be noted that the problem ofunemployment was not very big for them, in part due toour international aspirations. Our graduates establishedthe first Finnish shadow theatre Katputli (Kajani)and a new independent puppet company SixfingersTheatre (Turku). They work both nationally (as in theMukamas Theatre, in Tampere), and internationally –in Slovenia (the Tunteenpalo paper theatre), Denmark(the Reflection Theatre), and Norway (the Katta ISekken Theatre). They regularly receive local grantsand international awards, and some continue theireducation in such legendary schools as that of JeanLecocque in Paris.The education at the Department is not “text-book”, butproject-oriented. During their studies students realisea number of projects in which they can concentrateon one aspect of the profession or try themselves inseveral fields. Individual, pair and group projects arethe basis of the process. As there are always two classesof students studying at the Department at the same time– either 1st and 3rd, or 2nd and 4th years – both classes’curricula are closely related. The junior students arealways involved as performers in the senior students’projects. The senior students are required to involve thejuniors in their productions.There is no specific specialisation (puppet theatredesigner, constructor, performer, director) at theDepartment – every student takes part in all classes andworkshops – equally on puppet design, construction,manipulation, or directing. Of course, each student’sindividual talents, skills, and intentions are alwaystaken into consideration.The core of the process is workshops and masterclasses, each devoted to a certain specific formor aspect of puppetry. We have already had suchinternationally renowned guest-teachers as Eric Bass(USA), Fabrizio Montecchi and Bruno Leone (Italy),Davide Giovanzana (Switzerland), Rene Baker(Spain), Andrey Knyazkov and Yana Tumina (Russia),Lone Nidergaard (Denmark), Greta Bruggeman, PauloDuarte and David Girondin Moab (France), MichaelVogel (Germany). Duration of the workshops variesfrom one to six weeks. In-between workshops, theskills received are developed in the projects, tutored bythe staff instructors.The final project consists of two parts. First, a writtenproject - a 25-page essay on a chosen aspect of puppettheatre. Second, an artistic project - a maximum-30-minute show directed and/or designed by the graduate.There are no technical or other requirements exceptthat the show must demonstrate the graduate’s clearunderstanding of the form and content of puppetry.The final year ends with the Fanatik Figuras Festival,a showcase of the graduation projects, performedin the city of Turku for the professional jury and thegeneral audiences alike. The crowd of professionals ithas drawn, as jury and audience, for the past severalseasons, cosmopolitan and illustrious, could very wellmake the core of the future united Scandinavian schoolof puppetry.

images:“The Little Match Seller”, premiere 9th of May 2007at Turku Arts Academy, directed and designed by ElinaPutkinen”photo: Antti SumialaNukketeatteri Reaktori: Shamu, Skeleton in from themarionet varietee Jacques Umbrella.Puppets, director, actor: Aapo RepoPhoto: Aapo Repo13Kamran Shahmardan’s “Black and White” at TheatreImatra 2007 (black theatre)Teatteri Hevosenkenkä: “Spooky party”, premiere22.9.2007 Espoomanuscript Eero Ahre, Patrik Drake, Pekka Heiman,dir. Patrik Drake, scenes, dolls and dresses TeemuLoikas, actors Eero Ahre and Pekka Heiman. In thephoto count Konrad Kullervo von Kanckenhaus (EeroAhre) and the little ghost Hug.photo: Miska ReimaluotoPuppet Theater Akseli Klonk (Oulu): Iso Vihko (thenotebook 2007)photo: Jaani Föhr.

Sixfingers Theater: “Mid Winter Dream” - a mythicalretro science fiction performance inspired by thefinnish national epos “Kalevala”. A co-operationbetween Wolf Sign Theatre, Six Fingers Theater andTurku city theater. Puppets Iisa Tähtinen, scenographyJohanna Latvala, director Lars Wingård, text IshmaelFalke, puppeteers: Elina Putkinen, Maiju Puuppola andIshmael Falke.photo: Iisa TähtinenTurku Arts Academy ”I am not always the same”(2005), based on the life of Franando Pessoa, dir. DavidGirondin – Moab and Paolo Duartephoto Kari Vainio14Antti-Juhani Manninen: dr Jekyll and mister Hyde,premiere 2005 at Turku Arts Academy, actor: Antti-Juhani Manninenphoto: Kari VainiMusic Theater Kapsäkki: “The wooden boy” (2006),director Elina Lajunen, shows in Seurasaari museumarea. photo: Eero Grundström

The new wave of FinnishpuppetryCompared to many other European countries,Finland does not have a long history in puppetry.However, Finnish puppeteers have succeeded toturn it positive way. In the last few years, Finlandhas come out as a fresh, very interesting puppetrycountry. Besides traditional puppet theatres, anew generation is emerging, thanks to educationin Turku and Pieksämäki and also Adulta in theHelsinki area.The influence of education has also been noted outsideof Finland. Finnish puppeteers have gone to manyfestivals and many young artists continue studyingIshmael Falke is a founder of Sixfingers Theatre.Sixfingers has also become known abroad with theshow “Golemanual”, based on naked hands. After that,Sixfingers has actively worked in co-operation withlocal drama theatres. Ishmael wrote the manuscript forthe show “Midwinter dream”. This show was freelybased on the Kalevala and the premiere was at TurkuCity Theatre.Let’s ask what these young puppeteers think about theworld of puppetry?A short history about your road to puppetry. How didyou start to get interested in puppet theatre?Elina: When I was young I played violin and madehandcrafts. In the high school I made my first puppetshow. It was handpuppetshow Little Red Riding Hood.I didn’t have a proper wolf so I took a frog puppet withhuge mouth and I hooked up a piece of paper to it. Inthe paper there was a text WOLF. In that time I thoughtthat in puppet theatre actors are hidden. Another thingwas that I thought that puppetry contains all forms ofart. I wanted to play music, make things with my hands,write, paint and be on the stage, but hidden. The lastpart has changed, I don’t want to hide anymore.Ishmael: When I was young, I wanted to be an astronautand a garbage truck worker. I think that with puppetry,I have achieved a good place in the middle. Actually, IBy: Timo Väntsi15Elina Lajunenabroad.Elina Lajunen, Ilona Lehtoranta and Ishmael Falkebelong to this new wave of Finnish puppetry. ElinaLajunen graduated from Turku Arts Academy,Department of Puppet Theatre, in 2004. She hascombined folk music, puppetry and movement inher shows “The happiest man in the world” (DanceThetre Rollo), “Little Red Riding Hood” (Dancetheatre Hurjaruuth) and “The Wooden Boy” (MusicTheatre Kapsäkki). She also works in her own group,Nukkehallitus, in Helsinki. She is currently studyingin the International Theatre School Jacques Lecoq inParis.Ilona Lehtoranta is one of the most interesting soloperformers in Finland. After studying in Pieksämäkipuppetry courses, she founded the Teatteri Capelletheatre, in Jyväskylä. Ilona combines simple puppetsand visual elements in her shows, for both adults andchildren.got the puppetry disease when one day the woman wholater became my wife was cutting her hair in the yard. Ifound the hair on the ground and started to play with it– immediately it became alive!Ilona: I have always been interested in theatre. I haveperformed for nearly 20 years in many amateur theatresIshmael Falke

16and I was looking for a permanent place in the theatrefield. I left my job as a school teacher and started tostudy puppetry in Pieksämäki (in Central Finland).During my studies, a rather new world opened up tome. Then I founded my own solo puppet theatre TeatteriCapelle in 2002.Why do you want to tell a story with puppets?Elina: I want to create interesting, visual and musicalworlds and spaces. I am interested in to see thingsother way, to turn things upside down. I like toexplore possibilities of a human body with or withoutobjects and puppets. Puppets are full of humanity andweakness and the language of the puppets is movementand music. That’s my language.Ishmael: Out of all other art forms, puppetry is theclosest to alchemy. A puppet is a materialized metaphor,yet on stage it is alive and unexpected. As a puppeteeralchemist, I use this element of the unknown in mywork to make old stories new. That’s also why I workmainly with myths.Ilona: The way of storytelling by puppets is so symbolic,and because of it, it is very simple but at the same time,very effective. In it’s best, the story is being built in themind of the viewer.What is a good puppet show? And what is a bad one?Elina: A good puppet show is like good music. It respires.There has to be pleasure to play, movement, rhythmand drama. Something has to happen to someone. Badis bad, you know. There is place for bad things too. Anda bad puppet show can be a good art exhibition.Ishmael: In a bad puppetry show, I see the scenery, themanipulators and the technique. I think, ”interesting,they use this and this kind of puppet”. In a goodpuppetry show, I don´t see all that, I´m inside the story,I just breathe with the show.Ilona: All the pieces are put together well: themanuscript, staging, acting etc. The rhythm of a playis variable. A good puppet show gives space for theviewer’s own insight. Above all, a good show is donewith heart and the ability to read life. A bad one isopposite to that.Can you handle all kinds of subjects in puppet theatre?Are there some limits that you simply can’t do?Elina: There are no limits and there are limits. Itdepends on how you handle the subjects. What you doand how.Ishmael: You can handle everything in puppet theatre.However, I find myself hesitating long before I wouldhave the courage to do a show about children in war.I want to be sure that I can respect both a sensitivesubject and this sensitive art form, even though it issilly because in puppetry you never get a guarantee.Ilona: I think all subjects are possible, but I prefer tohave a humoristic point of view. For me, there’s nosense in concentrating on and only showing the darkside of the mind.Puppetry is slowly becoming more and more popularbut is still in the minority in Finland. Is there somethinggood and/or bad to be in the minority?Elina: Being in minority there’s not so many peopleto see us. But like other art forms in minority, circus,Finnish folkmusic and folkdance, things are becomingbetter and better. People are interested in what happensin minority. We still have surprises, new things to show,no money ant lot of work to do. That’s good and bad.Ishmael: In Finland, we lack institutionalised and wellbudgetedpuppet theatres that will employ us, we lackthe background of a traditional local puppetry and wesuffer from a public image of eccentric babysitters. Butwhat the hell – we are free to develop this art in anoriginal way, to surprise local audiences, to feel likereal pioneers!Ilona: The smaller the institution, the better it works.Small theatres are creative and flexible. But being inthe minority also means less support from the State.What do you think about Finnish puppetry right now?Elina: Finnish puppetry is like a weak, little animal.But it’s vivid and it respires. It has four limbs and thewill to move and walk.Ishmael: Because of the lack of an old, local puppetrytradition, the Finnish audience doesn’t expect usto use certain manipulation techniques or performcertain plays. This means that we get artistic freedomto develop our work. Another thing is that in Finland,cultural institutions nowadays gradually give puppettheatre more recognition. This promotes more initiativein puppetry productions.Ilona: Finnish puppetry is getting better right now.Thanks must be given to those grand old puppeteers whohave given a good example to the younger generation.Starting puppetry education in Turku Arts Academyis also a remarkable thing which has given respect topuppetry and ever since more often professional groupsand solo theatres are founded.I think the best thing in Finnish puppetry is ourconnection to nature. It means that we are open to wildideas. We have a powerful mythology to use but wealso have current technology to get in touch with otherworlds.What are the weakest points in Finnish puppetry?Elina: It has something old and something new butthose two things are not connected yet. It’s like ananimal who is afraid and lost and who believes that itslimbs are disparate.Ilona Lehtoranta

Ishmael: The Finnish audience still has a strongconception of puppet theatre as children’s entertainmentonly. It is a big step to make adult audience orientedpuppetry a known art in Finland. But still with adultaudience, in Finland, as everywhere else in the westernworld, our real opponent is not actor-based theatre, buttelevision.Ilona: I think they are only economical.What does Finnish puppetry need to become strongerand more interesting?Elina: Finnish puppetry need to be courageous, activeand open. It’s time to get up and move, work andperform. It’s also time to open our eyes in order to seeothers, other art forms and the audience. And makethem see us.Ishmael: Finnish puppetry needs wider recognition fromthe State and cultural institutions. From the puppetrymakers, we must dare to step out of kindergartensand theatres into everyday life: in bus stations, on thestreet, in hospitals, in pubs, in prisons. In other words,to encounter new audiences.Ilona: We need more respect, money and marketing.Imagine yourselves in 5 years time: what are you doingin the puppetry field?Elina: I will have my own theatre group Nukkehallitus(The Puppet Government) and I will be doing differentkinds of projects with puppets, music and movement.I’ll have a home with a big kitchen where I can invitepeople to come spend time, eat, dance and speak aboutlife, love and art and go to sauna. An I’ll dance thetango.Ishael: There I sit in the new Laboratory of TheatricalIllusions & Truths, located in the cellar of the newInternational Centre for Puppet Theatre in Turku,experimenting with puppetry’s most profoundquestions... and I try to keep an eye on my childrenso that they would not become puppeteers themselves(someone in the family has to have a descent job!)Ilona: I will do wonderful puppet shows!Your favourite character in puppetry (in your own showor somewhere else)?Elina: Sylvi. She is the old lady from the play “Thewooden boy”. In the play there is a scene where thewooden boy Johannes steals clothes of young Sylvi.Sylvi wants her clothes back. “You get a cake, if yougive my clothes back. A horse, a boat. I will be yoursister, mother, or your wife”, she says. The last oneworks. Sylvi and Johannes get married.Ishmael: ”Igor”, a combination of a glove and atiny rubber foam head. Igor is a sidekick characterwho loses his head every time we perform the show”Golemaunaul” with my group. He has such anexpression on his face that looks like he is well awareof his poor job, but he does it anyway. He is not smart,he is not beautiful, he is not a star, but I love him asa hard working colleague, and because it ok to feelamused when he loses his head.Ilona: The grasshopper, Pinocchio’s conscience (wasmy show). It/he was easy to handle and I loved hisvoice.<strong>UNIMA</strong> INFO FINLAND<strong>UNIMA</strong> Finland:www.unima.fiContacts to the Finnish puppet theaters and otherinformation.Studying puppetry in Finland:www.taideakatemia. fiPuppet departments own web-pages: www.nukkis.netcontact: anna.ivanova@turkuamk.fiFestivals and happenings:Bravo!International theatre festival for children and young people.Often also puppetry.9-16. March 2008, Helsinki, Vantaa and Espoowww.bravofinland.orgMukamasInternational Puppet theater festival 2008, organiser:Theater Mukamas12-17. May 2008, Tamperewww.mukamas.fiKuusankosken kansainvälinen lasten teatteritapahtumaInternational children theater festival13-18. May 2008 at Kuusankoskiwww.tnl.fiMusta ja Valkoinen / Black and White puppet theaterfestivalJune 2008, at ImatraOrganiser: Black and White Theaterwww.kulttuuri.org/mvHangö 17de Teaterträff5-8. June 2008 at HankoThe biggest Swedish speaking theater festival in Finland.www.teatertraff.orgHippalotArts festival for children31.7.-3. August 2008 at HämeenlinnaMusic, theater, puppettheater, dance etc.www.hameenlinna.fi/hippalot7+7 SOLOS!International solo puppet theatre festival27.-31. August, 2008 at RovaniemiThis year the programme consists of seven professionalperformances by international artists and seven shortersolo premieres produced in master-apprentices studioworkshops.Arranged by Lapland Puppet Theatre Association andTravelCase Theatre.Contact: Chairperson Johanna Latvala jolatval@ulapland.fi orLeila Peltonen leila.peltonen@pp3.inet.fi ( TravelCaseTheatre )The festival homepage will be opened at the end ofJanuary.Helsingin juhlaviikot15-31. august in HelsinkiThe biggest culturefestival in Finland. Theater, dance,music, happenings etc.www.helsinki.fi’Kangasala PuppettheatrefestivalSeptember 2008 at Kangasala, Organiser: PuppettheaterHupilainenwww.hupilainen.fiKesäaika päättyy / Summertime ends -theater happeningTheater and puppet theater, organiser: puppet theater AkseliKlonk24-26. October 2008 at Ouluwww.suomi.net/ykj/akFanatic FigurasFestival presents the final works of the graduatingpuppettheater students.In april-may 2009 at Turkuwww.taideakatemia.fiThe 7th International Barents Puppet Theatre FestivalOctober 2009 at Oulu and RovaniemiArranged by Barents Puppetry Network.Contact: Janne Kuustie akseliklonk@gmail.com (Oulu)Leila Peltonen leila.peltonen@pp3.inet.fi (Rovaniemi)17

Norwegian puppetry now:Separate performingart or bridgespanning artisticdisciplines?Norwegian puppet theatre appears to have entereda state of hibernation after a period of considerableattention, artistic experimentation and theestablishment of many newcomers. The recruitmentof fresh young artists in the new millennium has beenno more than moderate. <strong>UNIMA</strong>’s membership hasbeen halved in just a few years and a number ofthe puppet theatre institutions set up in the 1990shave partially or wholly shifted focus towardsother art forms. All the same, the art of animationis blossoming in Norway both on film and as a livephenomenon in the here and now. Perhaps it is assimple as that the art form is merely accommodatingitself to a society in the process of change?The traditional institutional theatresNorway still has two traditional theatre institutionswhich, in addition to other forms of performing arts,maintain their responsibility for puppet theatre: OsloNye Teater (established in 1952) and Riksteatret(established in 1976). Oslo Nye Dukketeatret’srepertoire this spring consists of Ferdinand the Bull byMonro Leaf and a new dramatisation of the Norwegianfolk tale Askeladden and the Blue Mountain’s ThreePrincesses. Riksteatret’s puppet theatre ensemble isalso putting its trust in a fairy-tale figure, in this casea witch: The Powder Witch is a dramatisation of apopular children’s book.Agder Teater and Hordaland Teater are two regionaltheatres which have puppet theatre as part of theirremit. Both institutions were founded in the early1990s when the championship of puppet theatre wasalmost guaranteed to result in financial backing fromthe nation’s cultural authorities. Agder Teater arrangesa large biennial International Puppet Theatre Festival(next scheduled for 2009). This top-quality festival,for which Giert Werring has had artistic responsibilitysince its inception in 1992, has done much to increaserecognition of the art of puppet theatre in Norway.Werring himself has made traditional hand-puppettheatre in a one-man booth his speciality, and thisspring he is to perform a piece firmly anchored in thegenre and based on a theatre text by Norwegian authorHenrik Wergeland, whose 200th birth anniversary iscelebrated this year.Hordaland Teater, having chosen a classic children’stheatre piece from the 1950s, may also be said to beputting its faith in the historical perspective. Karius andBactus, the story of two ’tooth trolls’, was written byThorbjørn Egner, Norway’s most produced dramatist.Puppet theatre as a scenic elementAlthough the puppet theatre ensembles at theinstitutional theatres retain a very traditional profilein their main repertoire, leaders of the parent theatreshave realised what a tremendous visual resource puppettheatre can be. Oslo Nye Teater, for example, in using apuppet theatre group to present the play within a play inits production of Hamlet, found the puppets to constitutea colourful, beautiful addition to the performance.Puppet theatre’s scenic function is even more clearlydemonstrated in Riksteatret’s and Rikskonsertene’s coproduction,@lice. Although this is primarily a musicand dance performance, theatre boss Ellen Horn was ina position to say: Riksteatret, in helping to develop theproject using puppeteers, presented the opportunity ofcreating a poetic, spectacular expression.The tendency to use puppet theatre as a visual,mobile scenic element can also be identified in manyindependent theatre groups. The hunt for a theatricalexpression which is rich in visual imagery is quiteapparent in current Norwegian theatre. This has leadto increasing numbers using elements of puppet theatredespite its not being their primary form of theatricalexpression.Independent puppet theatresThe number of professional and semi-professionalpuppet theatre groups is currently just under 30. Manyof those which were important 20 years ago are stillin existence. Some, such as Petrusjka Teater, have cutback on their activities. Tatjana Zaitzow, the leaderof Petrusjka Teater and one of Norway’s most fêtedpuppet theatre artists at home and abroad, continuesto work both as a scenographer and puppet-makerand has donated her entire life’s work – puppets andscenographies – to South Trøndelag Museum.The idea is not for it to be any kind of hushed museumbut a vibrant, magical house of puppet theatre! Thebuilding concerned is the old main building of themuseum grounds – a beautiful large brick buildingdrawn by Trondheim architect, Sverre Pedersen. ThereBy: Anne Helgesen21

22are two complete floors, plus loft space, with potentialfor exhibitions, workshops and, not least, all kinds ofthings for children. I’ve got loads of ideas and thoughtsas to different activities. My dream is for the PuppetTheatre House in Trondheim to become such a bigtourist attraction that the Norwegian Coastal Steameras to rearrange its arrival and departure times to fitin! Hopefully the building can be opened some timeduring 2008 since Petrusjka Teater will be celebratingits thirtieth anniversary this year, says Zaitzow.Other long-established puppet theatre artists, such asKjell Matheussen of Dårekisten Teater, have decidedto revive old favourites. His children’s TV series aboutLittle Blue was enormously popular on Norwegianscreens 24 years ago. Now the performances aresomething of cult events, full of childhood memoriesfor a young generation of parents. A number of otherolder puppet theatre practitioners have also discoveredthe benefits of nostalgia.Puppets and musicA number of well-established puppet theatre artists havechosen to undertake co-productions with musicians.Camilla Tostrup of Musidra Teater is playing Peterand the Wolf with two musicians while Knut Alfsenof Levende Dukker is presenting a popular puppetcabaret, called Jazzpuppet, with a jazz orchestra.Kulturproduksjoner (Culture Productions), in theirongoing collaboration with a young violinist andcomposer, have created the trilogy of work The SingingFiddle (2004), In Peer Gynt’s Realm (2006) and Swansover Ireland (2007).Katta’s Puppet Theatre Ensemble have been involvedin the reconstruction of Dmitri Shostakovich’s lostcartoon opera The Priest and Balda, his Servant andperform with an entire symphony orchestra and ananimated film. The puppeteers themselves are mantledin costumes which transform them into puppets.Dissolution of the narrativeKatta’s Puppet Theatre Ensemble is also workingwith projects which move away from the traditionaltheatrical event. In the museum project Grå Gubber, thepuppets are placed in a 12th century wooden building.There they live in the dark corners as the audienceassembles for a brief ten minutes before going on toother experiences in the museum. The event attractedconsiderable public attendance. In 6xReveenka theEnsemble mixes workshops and performance into anew form where different puppetry techniques areexplored, puppets made and played; in The VampireHunters the participants/audience have to create ascenographic landscape before the vampire puppet canbe lured to appear.It is precisely in these crossover forms between theatreand other types of performative events that we meetyoung Norwegian artists who have become involved inanimation and puppet theatre.Figurfantastene is run by pictorial- and puppet theatreartist Jon Mihle with musician Peter Paul Kantor. Here,music and the creation and performance of puppetsdevelop side by side. Long, linear narratives are besidethe point; it is the situations which count. Mihle worksin a landscape where pictorial art and theatre slideinto one another. The events created in his most recentproduction, Egg, spin off from two men trying toconstruct an egg-hatching machine.The young shadow puppet theatre group from Bergen,Skyggisane, grew out of the city’s student theatreand works in collaboration with the electronica bandCasiokids. This combination of music and shadowtheatre has been a great success, making theseperformers immensely popular at both concert-housesand music festivals. Artistic Director for Skyggisane,Aslak Helgesen, says: Our performances are a hybridbetween concerts and puppet theatre. We create shortstories and visualisations in the same way as a bandwrites songs. This episodic approach means that ourperformances have a varied visual expression. Since thestories we create are so short, we’ve found it necessaryto use clichés and references from popular culture toshort-cut the audience into what we’re trying to say.Icons and symbols have proven to serve our purposewell and we frequently use such imagery.As far as content is concerned, we’ve leapt fromcommunism v capitalism to hunting stories, sweet littlepussy cats and parodies of James Bond.Since the show has been developed over a long periodof time, the thematic content has been very varied. It’san advantage to us to be able to freely follow up newideas all the time. The disadvantage of course is that theaudience cannot be presented with a unified narrative,but then, neither is this expected in the context we’reworking in.Scenographers, puppet makers and pictorialartists.Popular culture, with its cartoons and computergames, is an important source of inspiration formany of the young artists finding their way to whatwe might provisionally term puppet theatre’s outerlimits. They have little contact with the traditional<strong>UNIMA</strong> milieu, choosing new materials and inventingtheir own animation techniques. Steinar Kaarstein ofEffektmakeren, whose profession is making specialeffects for film and theatre, finds it natural to includepuppet-making. He says: I love experimenting withnew materials; this kind of research has a value all of itsown. There are new things available all the time. I spenda lot of time on the net keeping up-to-date and travelround to exhibitions dealing with this kind of material.I’m not particularly involved in theatre even thoughI’ve made puppets for both theatre and children’s TV.It’s the puppets I care about. Right now I’m workingon 30 zombies for a Norwegian film project. It’s a hugeorder, and great fun!The Norwegian puppet theatre milieu underwent atraumatic time when the dedicated education at theAcademy of Puppet Theatre at Fredrikstad College(set up in 1991) was reorganised, following a lengthy,turbulent process, into the Academy of Performing Arts.Many of the students present during the transitionalphase, however, demonstrate a liberating crossoverbetween actor-related theatrical forms, puppet theatreand pictorial art. Camilla Lillengen of Sus i Serkencreates both costumes for theatre and theatricalpuppets, but she is perhaps at her most original whencreating sculptural costumes which transform playersinto puppets. This is reminiscent of the Russian Ballet,Bauhaus and other modernist experimentation withcostume, theatrical puppets and übermarionettes.Katrine M. E. Strøm of Katma Productions creates

marvellous fairy-tale worlds for children where adultsare scarcely allowed access. Sukkersirkus (The SugarCircus) is a provocative event in which children canstuff themselves with as many sweets as they want,Vidunderkammer (The Chamber of Wonder) a mazeof curious experiences which the young audiencewanders through at will. Katma’s visual expressionmixes a childish dream-world with the glamour ofadvertising and elements of popular culture. Strøm,who works out of Andenes in North Norway, has alsoincorporated her regional allegiance into her artisticexpression. She is Festival Artist of the Year at theFestival Plays in North Norway.<strong>UNIMA</strong>’S role in the new puppet theatre landscapeIn a situation where “the new puppet theatre” is on theway to becoming a bridge between art forms rather thana separate performance art, <strong>UNIMA</strong> is experiencingdifficulties in finding both direction and strategy.One answer, among others, has been the furthereducation course in Puppet Theatre at Oslo Collegeunder the direction of <strong>UNIMA</strong> Norway’s leader,Svein Gundersen. In addition, <strong>UNIMA</strong> and Oslo NyeTeater have inaugurated the “Fri Figur” festival, to bearranged biannually and to present Norwegian PuppetTheatre in the Norwegian capital.images:Riksteatret and Rikskonsertene’s no-expense-spareddance and concert performance @lice concerns a younggirl who meets her dream man on the internet. Videoprojections and live puppetry form a frame around theaction and are used as moving scenic elements. Photo:Tormod Lindgren. Homepage: www.riksteatret.noBoth institutional theatres and independent groups aremaking more frequent use of puppet theatre sequencesin their performances. Here the puppeteers of Oslo NyeDukketeatret perform in the parent theatre’s productionof Hamlet. Photo: Leif Gabrielsen. Homepage: www.oslonye.noOslo Nye Dukketeatret are showing the soloperformance of Ferdinand the Bull with puppeteerMarianne Edvardsen. Photo: Leif Gabrielsen.Homepage: www.oslonye.no23Tatjana Zaitzow of Petrusjka Teater has donated herartistic life’s work to Trøndelag Folk Museum. Autumn2008 will see the opening of a lively museum buildingfull of her puppets and scenographic works. At the sametime, the opening will mark Petrusjka Theatre’s 30thanniversary. Photo: Per Christiansen.Hordaland Teater’s puppet theatre performance thisspring is the 1950s children’s theatre classic about thetooth-trolls Karius and Bactus. The performance is acertain winner. Norwegian children have thus beenlearning they have to brush their teeth for over fiftyyears! Photo: Tor Erik H. Mathiesen. Homepage:www.hordaland-teater.no

Many young adults will be given the chance to relivepuppet theatre performances from their childhood withthe revival of old successes. Dårekisten’s performanceof Little Blue is but one example. Homepage: www.darekisten.noThe visual and musical elements are very much to thefore in Kulturproduksjoner’s performances. ViolinistMartine Lund Hoel is the central figure of theirperformance In Peer Gynt’s Realm. Storytelling, setdesign and puppets all yield to her playing. Homepage:www.kulturprod.no24Musidra Teater is Norway’s oldest independent theatregroup. The company has always worked a great dealwith music and this is now paying off in their musictheatre performance of Peter and the Wolf.The Priest and Balda, his Servant is based on DmitriShostakovich’s lost cartoon opera. The performanceis a collaborative piece with a symphony orchestra,animation film and puppet theatre. Katta’s PuppetTheatre Ensemble perform inside large ’humanettes’.Their stylised movements form the core of the piece,with mime artist Pelle Ask performing inside the centralpuppet, Balda. Photo: Morten Andreassen Homepage:www.kattas.no