Protecting the - LIFE Priolo - spea.pt

Protecting the - LIFE Priolo - spea.pt

Protecting the - LIFE Priolo - spea.pt

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

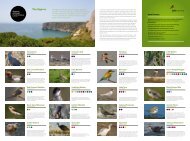

<strong>Protecting</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Priolo</strong>Once abundant, <strong>the</strong> AzoresBullfinch has come close toextinction but has managedto hang on – so far. DominicMitchell looks at its verytroubled past and to <strong>the</strong>future, and reveals whyBirdwatch has chosento become a BirdLifeSpecies Championto help protect<strong>the</strong> species.Above: endemic to montane laurelforest in <strong>the</strong> east of São Miguel, AzoresBullfinch is a top priority case forconservation action. Background photo:<strong>the</strong> spectacular vista at Pico da Vara.PEDRO MONTEIROEven on a rainy day, <strong>the</strong> landscapeof <strong>the</strong> hills towards <strong>the</strong> easternend of São Miguel is majesticand imposing. Such days arefrequent here, as <strong>the</strong> verdant landscape ofthis largest island in <strong>the</strong> Azores suggests.Rich green fields, lush hedgerows,fragments of laurel forest and statelycedars are <strong>the</strong> main elements of a wellwateredcountryside, which in inclementwea<strong>the</strong>r seems permanently hemmed inby a puffy grey ceiling of low cloud.It’s a picture of tranquillity and ruralbeauty, even if <strong>the</strong> landscape itself is farfrom ‘natural’. A sprawling patchwork offields, divided from each o<strong>the</strong>r by stonewalls painstakingly built from lava rock,indicates that large areas of <strong>the</strong> island havebeen given over to agriculture. Cows are adominant feature <strong>the</strong>se days, thoughhistorically it was orchards; cultivation oforanges was big business on São Miguel in<strong>the</strong> 19th century, and <strong>the</strong>rein lies a story.Persecuted ‘pest’Before settlers forever altered its landscape,much of <strong>the</strong> island was covered in pristinelaurel forest and o<strong>the</strong>r native vegetation.The outlook <strong>the</strong>n from <strong>the</strong> summit of Picoda Vara, <strong>the</strong> island’s highest point, wouldhave looked very different, probably akinto an evergreen wilderness.And like its relative neighbours in <strong>the</strong>warm waters of <strong>the</strong> Atlantic, Madeira and<strong>the</strong> Canary Islands, this habitat was hometo a unique bird: not a species of pigeon,as flourish elsewhere, but a bullfinch.Quite different in plumage and choice ofhabitat from <strong>the</strong> familiar pink, grey, blackand white Bullfinch of mainland Europe,this pinkish-brown and black speciesthrived in <strong>the</strong> native vegetation of easternSão Miguel.But as colonisation came, so too <strong>the</strong>landscape changed.With a growingpopulation to house and feed, <strong>the</strong> spreadof settlements brought dramatic changesto <strong>the</strong> island. Large swa<strong>the</strong>s of forest wereApplying control measures to invasivevegetation involves hard hiking to accessremoter parts of <strong>the</strong> bullfinch’s range.Commonly thought of as ‘giant rhubarb’,Gunnera develops leaves up to 2 m inlength and can smo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> forest floor.Low cloud cloaks a hillside where <strong>the</strong>project’s workforce has cleared a largestand of ‘exotic’ Japanese Red Cedars.SPEA-<strong>LIFE</strong> PRIOLOCARLOS SILVA (SPEA)DOMINIC MITCHELL38 BIRDWATCH • APRIL 2008

Critically Endangered birdsJOAQUIM TEODÓSIO (SPEA)cleared, and by <strong>the</strong> late 19thcentury orange orchardsproliferated in many places.For a while <strong>the</strong> AzoresBullfinch, or <strong>Priolo</strong> to <strong>the</strong> locals, maynot have been seriously harmed by <strong>the</strong>changes, despite <strong>the</strong> destruction of laurelforest. Indeed, it was perhaps evenprospering, with <strong>the</strong> buds of <strong>the</strong> orangetrees providing a new source of food. Butthat newly acquired habitat was to hastenits downfall: mirroring <strong>the</strong> situation inEngland, where Bullfinches were regardedas pests in orchards and huntedaccordingly, a bounty was placed on <strong>the</strong>head of every bird. Many wereslaughtered by <strong>the</strong> fruit growers, andthose that survived had an ever-shrinkingarea of core habitat within which <strong>the</strong>ycould breed and feed.A fur<strong>the</strong>r blow was struck when <strong>the</strong>need for timber provoked a forestry boom.Japanese Red Cedars were planted in vastswa<strong>the</strong>s across <strong>the</strong> island’s eastern hills,fur<strong>the</strong>r swamping <strong>the</strong> dwindling stands ofnative laurel. Coupled with <strong>the</strong> voraciousspread of o<strong>the</strong>r exotic flora, notably YellowgingerLily, Lily of <strong>the</strong> Valley and AustralianCheesewood, at <strong>the</strong> expense of nativevegetation, <strong>the</strong> bullfinch’s habitat wasvanishing fast – and with it <strong>the</strong> birds.Today, for all its scenic splendour, verylittle remains of <strong>the</strong> original landscape of<strong>the</strong> area around Serra da Tronqueira.That<strong>the</strong>re is anything left at all is not down toluck or coincidence: ra<strong>the</strong>r, it is a result ofcommon sense prevailing in <strong>the</strong> nick oftime to try and ensure that what is nowEurope’s most Critically Endangered birddoes not become its first avian extinctionsince <strong>the</strong> Great Auk.With São Miguel’s orange industrylong since gone and Azores Bullfinch nowafforded full protection, <strong>the</strong> emphasis ison consolidating <strong>the</strong> bird’s population in<strong>the</strong> remaining core area of habitat whereit still clings on – less than 60 squarekilometres of hillside and valley aroundPico da Vara.The exact number of bullfinches isunknown, having been estimated at 200-300 birds in <strong>the</strong> 1990s and slightly moresince <strong>the</strong>n; point-countsurveys since 2002have recently indicated a rise toan estimated 340 individuals, asign that perhaps at last <strong>the</strong>decline is being reversed.Work in progressMuch has been done already to help thisspecies, but it’s only when you see <strong>the</strong> scaleof <strong>the</strong> problem first-hand that you appreciatehow much it is a work in progress. In fact,it will never be completed. I was shown<strong>the</strong> daunting task that lies ahead by <strong>the</strong> coordinatorof <strong>the</strong> SPEA-<strong>LIFE</strong> <strong>Priolo</strong> project,JoaquimTeodósio, who is responsible for<strong>the</strong> daily marshalling of a small army ofstaff, labourers and volunteers. He explainedthat <strong>the</strong> extent to which invasive flora hasspread in this area means that controlmeasures will always be needed to preventit re-establishing a stranglehold on <strong>the</strong>fragile remnants of native forest. Effectivecontrol on this scale involves a sizeableworkforce, and that in turn means money.Previously, significant funding for <strong>the</strong>fieldwork undertaken by SPEA, Portugal’sBirdLife partner, has come from <strong>the</strong> EULife Fund. But after five years that will soonbe running out.With so much alreadyachieved – including <strong>the</strong> building of a<strong>Priolo</strong> Environmental Centre which hasworked wonders to raise <strong>the</strong> species’profile on <strong>the</strong> island – it would be a tragedyfor <strong>the</strong> species to suffer ano<strong>the</strong>r setback now.For this reason, Birdwatch has committedto becoming a BirdLife Species Championfor <strong>the</strong> Azores Bullfinch.There is a longway to go, but as a first step we have alreadycontributed £10,000 towards work tobenefit <strong>the</strong> species, and more investmentwill follow over <strong>the</strong> next two years. Ifyou’d like to help too, you can – please seepage 25 of this issue and also visitwww.justgiving.com/priolo. Updates on<strong>the</strong> species and our involvement willappear regularly on <strong>the</strong> Birdwatch website –watch this space. ■AcknowledgementsThanks to Joaquim Teodósio, Ricardo Ceiaand <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> SPEA-<strong>LIFE</strong> Project onSão Miguel, to David Howlett for his helpfulinput, and to Archipelago Azores Ltd forfacilitating travel (tel: 01768 775672;email: info@azoreschoice.com; web:www.azoreschoice.com).Why <strong>the</strong> truly rarebirds matter mostWhile common birdsenrich our dailyexistence with <strong>the</strong>irbeauty, voice andbehaviour, it is usuallyrare birds that fuel ourfascination and addan extra dimension ofinspiration when weare lucky enough to see <strong>the</strong>m.Showing our county recorder Surrey’s40th Firecrest, in <strong>the</strong> big Yew in my suburbangarden, was a defining moment for me at <strong>the</strong>age of 13. Celebrating my 400th British tick(a Siberian Thrush at Burnham Overy inNorfolk) was ano<strong>the</strong>r major milestone 21years later.But when I joined BirdLife InternationalI quickly gained a new perspective on rarity.Learning that more than half <strong>the</strong> world’s10,000 species were in decline, 12 per centwere threatened with extinction and <strong>the</strong> 189most Critically Endangered faced imminentextinction really pricked my conscience.Previously, rarity had been my recreationalraison d’être, but now I saw it in ano<strong>the</strong>rlight.Raising funds for <strong>the</strong> BirdLife PreventingExtinctions Programme is my new mission,and time is of <strong>the</strong> essence. Our objective isto reverse <strong>the</strong> fortunes of all globallythreatened birds by appointing a worldwidenetwork of Species Guardians to providespecific conservation action, while recruitinga community of Species Champions toprovide <strong>the</strong> funds to pay for it.With <strong>the</strong> generous support of Birdfair –our first international programme sponsor –and a growing number of SpeciesChampions like Birdwatch and many o<strong>the</strong>rorganisations and individuals around <strong>the</strong>world, we’re making strides in <strong>the</strong> rightdirection.Most birders haven’t had <strong>the</strong> chance tohelp prevent extinctions before, but now weall can. Here’s how:• Visit www.justgiving.com/priolo andmake a donation to help fund AzoresBullfinch conservation.• Attend Birdfair this August – your entryfee will count towards funds raised forCritically Endangered bird conservation.• Purchase Rare Birds Yearbook, ano<strong>the</strong>rworthwhile way of contributing toconservation coffers (a percentage ofeach copy sold goes to BirdLife).To find out how you or your companymight help us by becoming a BirdLifeSpecies Champion, please contact me atspecies.champions@birdlife.org.Bird extinctions affect us all – let’s dosomething about it before it’s too late.Jim LawrenceBirdLife Preventing ExtinctionsProgramme Development ManagerAPRIL 2008 • BIRDWATCH 39

Critically Endangered birdsA volunteer abroadThere’s plenty that birders in Britain and elsewherecan do to help <strong>the</strong> Azores Bullfinch, including workin <strong>the</strong> field. Here, Dave Howlett recounts his time asa volunteer on <strong>the</strong> SPEA-<strong>LIFE</strong> <strong>Priolo</strong> Project.Ifirst became aware of <strong>the</strong>Azores Bullfinch and itspredicament through mystudies in ornithology atBirmingham University. So itwas that while on a familyholiday in São Miguel I took <strong>the</strong>opportunity of a day’s field trip in<strong>the</strong> company of Ricardo Ceia, anornithologist working on <strong>the</strong> EU Life<strong>Priolo</strong> project based in Nordeste, in <strong>the</strong>hope of seeing one of <strong>the</strong>se birds.We were successful, but it turned outthat seeing <strong>the</strong> bird was just <strong>the</strong> beginningof my interest.The more I learnt about <strong>the</strong>species and <strong>the</strong> conservation work beingco-ordinated on its behalf by SPEA(BirdLife in Portugal), <strong>the</strong> more interestedI became in <strong>the</strong> possibility of helping on<strong>the</strong> project as a volunteer.My appetite was fur<strong>the</strong>r whetted whenRicardo subsequently sent me details of afull year’s programme of volunteeropportunities.This was wide-ranging and,in addition to working directly with <strong>the</strong>birds, offered o<strong>pt</strong>ions to be involved withhabitat management and restoration aswell as education and awareness activitiesassociated with <strong>the</strong> establishment of a<strong>Priolo</strong> Environmental Centre in a forestpark near Nordeste.After discussions with JoaquimTeodósio, <strong>the</strong> Project Co-ordinator, on <strong>the</strong>SPEA <strong>Priolo</strong> project stand at Birdfair, where<strong>the</strong> <strong>Priolo</strong> was being heavily promoted, Iarranged for a two-week stay in <strong>the</strong> Azoresin October 2007.I had expressed a preference to beinvolved in field work with <strong>the</strong> birds<strong>the</strong>mselves, and a draft plan was availablefor discussion on my arrival. It was agreedthat I would initially undertake monitoring<strong>Priolo</strong>s and <strong>the</strong>ir feeding behaviour. Mymentor for this work was Sérgio Timóteo,and <strong>the</strong> initial task was a botany lesson,followed up in <strong>the</strong> field, to enable me torecognise <strong>the</strong> plant species onwhich <strong>the</strong> birds might40 BIRDWATCH • APRIL 2008be found feeding.The datarecording system was alsoexplained, as was <strong>the</strong> codingsystem used on <strong>Priolo</strong>s that hadbeen ringed.While monitoring<strong>the</strong> birds <strong>the</strong> following itemswere recorded: site (name and gridreference); time; status of bird; ringdetails, if any; bird behaviour, particularlyfeeding; and if feeding, <strong>the</strong> plant speciesbeing used.When possible, faecesdeposited by sighted birds were collected.These were subsequently despatched toMadrid for laboratory analysis to assessfern spore germination rates from faeces.After a couple of days I was deemed fitto carry out monitoring in <strong>the</strong> fieldwithout my mentor. During this period Irecorded <strong>Priolo</strong>s feeding on acacia, whichwas apparently a first – so volunteers canmake discoveries as well as <strong>the</strong>professionals! The monitoring work wascarried out in relatively remote andmountainous terrain, and could at timesbe quite physically demanding; it workedwonders for my waist-line, though!My o<strong>the</strong>r main field task was predatormonitoring. Rats and possibly Stoats preyon <strong>Priolo</strong> eggs and chicks, but beforecontrol measures can be contemplated itis necessary to establish <strong>the</strong> distributionand relative abundance of <strong>the</strong>se animals.This is undertaken by two-man teamssetting lines of traps which record <strong>the</strong>presence of <strong>the</strong> animal without actuallycatching it.The traps consist of squaresectionplastic tubes measuring 600 x 100x 100 mm and fitted with a central padsoaked in food colouring. Paper sheetsplaced at each end of <strong>the</strong> tube are usedto record <strong>the</strong> footprints of <strong>the</strong> animalpassing over <strong>the</strong> dye.The tubes werebaited with peanut butter for rats andrabbit meat for Stoats, and set in linesof 10 at 50-m intervals for <strong>the</strong>former and in lines of fiveJOAQUIM TEODÓSIO (SPEA)Want to be a <strong>Priolo</strong> volunteer?If you want to work in <strong>the</strong> field or knowmore about <strong>the</strong> project to conserve thisCritically Endangered species, pleasego to <strong>the</strong> <strong>LIFE</strong> <strong>Priolo</strong> micro website atwww.<strong>spea</strong>.<strong>pt</strong>/ms_priolo. Click on‘Projectos SPEA’/Life <strong>Priolo</strong> and <strong>the</strong>nfollow <strong>the</strong> link to <strong>the</strong> English languageversion. The team wants to hear from you!at 100-m intervals for <strong>the</strong> latter.The records are collected and are <strong>the</strong>nsubjected to statistical analysis to build apicture of distribution and abundance.Preliminary conclusions after summer andautumn monitoring demonstrate ageneral presence of rodents in <strong>the</strong>mountains, but a relatively low abundanceof mustelids for <strong>the</strong> same area. Fur<strong>the</strong>rresults are awaited.It was an honour and privilege to be<strong>the</strong> first overseas (that is non-Portuguese/Azorean) volunteer on <strong>the</strong> project, and Ihad a very enjoyable and enlightening twoweeks thanks to <strong>the</strong> hospitality andsupport of my SPEA colleagues. It wasgood to be able to contribute positively tothis important project, and it is gratifyingthat <strong>the</strong> work can continue thanks in nosmall part to <strong>the</strong> support of BirdlifeInternational Species Champions such asBirdwatch. ■Volunteering can be demanding if youwant to assist with practical measures in<strong>the</strong> field, but very satisfying to know thatyour efforts are making a real difference.