priciples of insecticide use in rice ipm

priciples of insecticide use in rice ipm

priciples of insecticide use in rice ipm

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

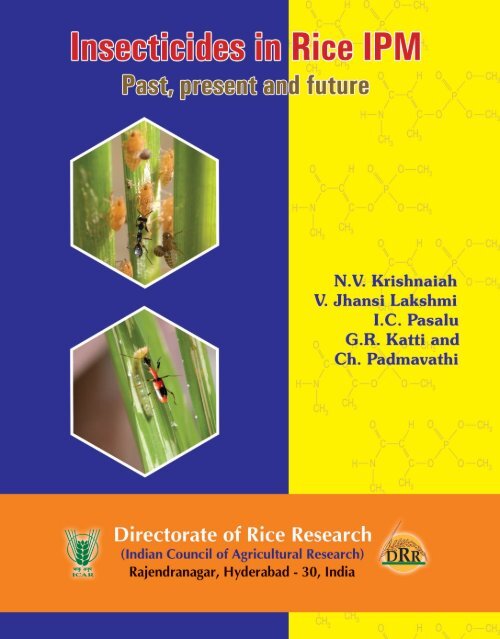

DRR Technical Bullet<strong>in</strong> 30/2008<br />

Correct citation :<br />

N.V. Krishnaiah, V. Jhansi Lakshmi, I.C. Pasalu, G.R. Katti and Ch. Padmavathi, INSECTICIDES IN RICE<br />

IPM PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE. Technical Bullet<strong>in</strong> No.30, Directorate <strong>of</strong> Rice Research, Hyderabad,<br />

A.P. India – pp : 146<br />

Published by :<br />

Dr. B.C.Viraktamath<br />

Project Director<br />

Directorate <strong>of</strong> Rice Research<br />

RajendraNagar, Hyderabad- 500 030, India<br />

Tel : +91 -40-24015120,2401 5026-39<br />

Fax : +91-40-2401 5308<br />

Website : www.drricar.org<br />

Email : pd<strong>rice</strong>@drricar.org<br />

Designed by :<br />

S. Nagaraj<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted by :<br />

Suneetha Offset Pr<strong>in</strong>ters<br />

# 4-5-716/3, Kuthibguda, Koti<br />

Hyderabad - 500 027. A.P. India.<br />

Ph : +91-40-24657269, 24761780.

FOREWORD<br />

Rice, the staple food <strong>of</strong> more than half <strong>of</strong> human population is grown <strong>in</strong> 153.9 million hectares <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world with a production <strong>of</strong> 618million tones and a productivity <strong>of</strong> 4.02 tones /ha.<br />

India ranks first <strong>in</strong> the world <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> area with 44.3 million hectares. But our productivity is only 3.01<br />

t/ha, which is below world average. Insect pests, diseases and weeds ca<strong>use</strong> considerable are the<br />

major deterrents <strong>in</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>rice</strong> productivity <strong>in</strong> the country. Among these, <strong>in</strong>sect pests alone ca<strong>use</strong><br />

about 10% loss <strong>in</strong> yield. To avert the damage by these <strong>in</strong>sect pests, farmers are forced to apply<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s.<br />

There is vast <strong>in</strong>formation generated on the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s, methods <strong>of</strong> application and<br />

associated problems like <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> resistance, pest resurgence, secondary pest outbreaks, effects<br />

on non-target organisms etc. <strong>in</strong> all the major <strong>rice</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g countries dur<strong>in</strong>g the last 40 to 45 years <strong>of</strong><br />

post green revolution era. Entomologists at our Directorate have made untir<strong>in</strong>g efforts <strong>in</strong> gather<strong>in</strong>g<br />

almost the vast <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> usage <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> with special emphasis on <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s as a<br />

component <strong>of</strong> IPM.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>formation has been arranged thematically and presented <strong>in</strong> an easy and readable way. This<br />

should serve as a source <strong>of</strong> the past and present knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> utilization <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>. This<br />

should also serve as a ready reckoner with the most updated <strong>in</strong>formation on all aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s<br />

for the researchers, students, agrochemical agencies and those engaged <strong>in</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> production<br />

and evaluation <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>.<br />

(B.C. Viraktamath)<br />

Project Director

PREFACE<br />

Insect pests, <strong>in</strong> general, damage crops result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an yield loss <strong>of</strong> about 10%. In case <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> also,<br />

<strong>in</strong>sect pests ca<strong>use</strong> about 10 to 15% reduction <strong>in</strong> yield as evidenced by multi-location experiments<br />

conducted under AICRIP for the last 40 years. To avert these losses, <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest management<br />

(IPM) is adopted as a national policy <strong>in</strong> India. In IPM, the major emphasis <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> is given for development<br />

<strong>of</strong> varieties resistant to <strong>in</strong>sect pests. However, there are no sources <strong>of</strong> good level <strong>of</strong> resistance, even<br />

to major <strong>in</strong>sect pests like stem borer and leaf folder. For brown planthopper and whitebacked<br />

planthopper, the level <strong>of</strong> host plant resistance is only moderate. Good level <strong>of</strong> resistance is available<br />

for gall midge, but the problem <strong>of</strong> biotypes is crippl<strong>in</strong>g the release <strong>of</strong> resistant varieties suitable for<br />

all areas. Pheromones have come to a stage <strong>of</strong> practical exploitation only <strong>in</strong> case <strong>of</strong> stem borer. The<br />

cultural methods like optimum fertilizer application, clean cultivation etc. are be<strong>in</strong>g followed as <strong>in</strong><br />

other crops. In the given scenario, <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> application to protect <strong>rice</strong> crop is becom<strong>in</strong>g a necessary<br />

evil, which is forc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>rice</strong> entomologists to cont<strong>in</strong>ue research to fully exploit the potential <strong>of</strong> this<br />

component <strong>of</strong> IPM.<br />

For quite some time, there were misunderstand<strong>in</strong>gs about the role <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM. Some<br />

entomologists argued that IPM means completely avoid<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> usage, but, the practical field<br />

situation under farmers’ conditions is entirely different. Rice farmer has to resort to <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> susceptible<br />

varieties for their own obvious reasons and are forced to apply <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s whenever some pest<br />

problems arise.<br />

Unfortunately, <strong>in</strong>ternational organizations have discont<strong>in</strong>ued the <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> evaluation programmes<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>. Hence, national programs like AICRIP have to shoulder the responsibility <strong>of</strong> generat<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> new molecules <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s aga<strong>in</strong>st all the major and m<strong>in</strong>or<br />

<strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong>. This has been effectively executed under AICRIP for the last forty years. Therefore,<br />

it is apt to review the whole scenario <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> evaluation program under AICRIP along with<br />

related efforts by entomologists from other <strong>rice</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g countries like Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Japan, Korea, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es,<br />

Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Malaysia.<br />

There is no comprehensive source <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation available on the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

major <strong>in</strong>sect pests. Hence, we the entomologists at DRR made an attempt <strong>in</strong> our own humble way to<br />

collect, organize and thematically present the whole <strong>in</strong>formation on various aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM, its past, current status and future directions.<br />

N.V. Krishnaiah, V. Jhansi Lakshmi, I.C. Pasalu,<br />

G.R.Katti, Ch.Padmavathi

CONTENTS<br />

Integrated Pest Management <strong>in</strong> Rice 1<br />

Bio-ecology <strong>of</strong> major <strong>rice</strong> pests 6<br />

Insecticides <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM 16<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM 21<br />

Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>rice</strong> <strong>in</strong>sect pests 31<br />

Methods and tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> application <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> 43<br />

Systemic nature <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>: the concept and practice 50<br />

Molecular approaches for <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> utilization <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> 54<br />

Safety <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s to natural enemies <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem 59<br />

Insecticide resistance <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> pests 67<br />

Insecticide <strong>in</strong>duced resurgence <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> pests 79<br />

Botanical <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> pest management 89<br />

Biopesticides and their <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM 101<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> green leafhopper, the vector <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> tungro disease with <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s 104<br />

Future strategies 109<br />

References 112<br />

Acknowledgements 146

Introduction<br />

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT IN RICE<br />

Rice is grown ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> Asian countries like Ch<strong>in</strong>a, India, Japan, Korea Republic, Srilanka, Pakistan,<br />

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, Thailand etc. More than 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> is produced and<br />

consumed <strong>in</strong> these Asian countries. Rice is biologically, ethologically and culturally bound with the life <strong>of</strong><br />

Asians. The total <strong>rice</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g area <strong>in</strong> the world is 153.9 million hectares with a production <strong>of</strong> 618 million<br />

tons <strong>of</strong> rough <strong>rice</strong>. Among the <strong>rice</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g countries, India occupies number one position with regard<br />

to area with 44.3 million hectares followed by Ch<strong>in</strong>a (29.3 million ha.). However, with regard to the<br />

productivity or per hectare yield <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong>, India occupies 15th or still lower position with 3.01 t./ha <strong>of</strong> rough<br />

<strong>rice</strong>, compared to Ch<strong>in</strong>a (6.26t./ha.), Japan (6.65t./ha.), Korea Republic (6.57t./ha.), Indonesia (4.57t./<br />

ha.), Malaysia (3.36t./ha.),The Philipp<strong>in</strong>es(3.65t/ha.), SriLanka(3.51t./ha.)etc.(FAO,2006). The major<br />

reasons for low productivity <strong>in</strong> India are the losses due to <strong>in</strong>sect pests, diseases and weeds. Insect pests<br />

alone are responsible for 10-25% yield losses <strong>in</strong> India.<br />

There are several methods like host plant resistance, cultural measures, optimum time <strong>of</strong> sow<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

transplant<strong>in</strong>g, recommended and balanced fertilizer application, water management, biological control<br />

methods like conservation and utilization <strong>of</strong> parasitoids and predators, biorational methods like <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>sect pheromones, botanicals and need based <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong>. Utilization <strong>of</strong> as many techniques as<br />

possible <strong>in</strong>to a unified programme is called <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest management or IPM. This has been accepted<br />

and attempted as a national policy <strong>in</strong> India.<br />

There are over a dozen def<strong>in</strong>itions propounded by various authors for the concept <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest<br />

management (IPM). However, the salient po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> all the def<strong>in</strong>itions are that<br />

(1) IPM is an ecosystem approach <strong>in</strong> pest management <strong>in</strong> which all the natural<br />

forces <strong>of</strong> pest suppression are strengthened.<br />

2) One or more methods <strong>of</strong> pest suppression are employed <strong>in</strong>to a unified command.<br />

3) The option(s) <strong>of</strong> least possible disturbance <strong>in</strong> the agri-ecosystem like <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem is (are)<br />

employed.<br />

4) With the awareness <strong>of</strong> the limitations imposed by the fact that agro-ecosystems are “artificial<br />

ecosystems”.<br />

Philosophy <strong>of</strong> IPM<br />

The <strong>in</strong>sects have come <strong>in</strong>to existence dur<strong>in</strong>g the course <strong>of</strong> evolution about 300 million years ago, while<br />

man appeared on the scene <strong>of</strong> evolution only about one lakh years ago or even later. The <strong>in</strong>sects have<br />

<strong>in</strong>vaded all spheres <strong>of</strong> earth both terrestrial and aquatic. They adapted to all types <strong>of</strong> food materials<br />

available on the planet. They developed physiological mechanisms to cope up with any adverse conditions<br />

1

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

<strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> biotic and abiotic factors. Above all, the <strong>in</strong>sects have immense reproductive potential. The<br />

<strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>of</strong> crops <strong>in</strong> general and <strong>rice</strong> <strong>in</strong> particular developed high physiological abilities <strong>of</strong> adaptation.<br />

For <strong>in</strong>stance, the fact that there are no sources <strong>of</strong> host plant resistance to many <strong>rice</strong> <strong>in</strong>sect pests like stem<br />

borers, leaf folders, <strong>rice</strong> hispa, gundhi bug etc. is an expression <strong>of</strong> their high level <strong>of</strong> adaptation to <strong>rice</strong><br />

plant. As <strong>rice</strong> is grown <strong>in</strong> different ecosystems, like irrigated, deep water, upland and ra<strong>in</strong>-fed lowland, the<br />

adaptation <strong>of</strong> different pests is f<strong>in</strong>e-tuned to suit that particular ecosystem. Termites and root aphids are<br />

present <strong>in</strong> uplands only, while gall midge is conf<strong>in</strong>ed ma<strong>in</strong>ly to irrigated <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem.<br />

The major philosophy <strong>of</strong> IPM is to live with the <strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> attempt<strong>in</strong>g to completely elim<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

them from <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem. At the same time the farmer has to safe guard the yield levels <strong>of</strong> the crop.<br />

Hence, he can tolerate only up to certa<strong>in</strong> level <strong>of</strong> pest population or damage. Hence, the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

economic thresholds (ETLs) was arrived at.<br />

Concept <strong>of</strong> ecosystem<br />

“Ecosystem <strong>in</strong> general is any unit hav<strong>in</strong>g liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms and non-liv<strong>in</strong>g environment representative <strong>of</strong><br />

an area with effective <strong>in</strong>teraction between the liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms and the non-liv<strong>in</strong>g environment, lead<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

trophic levels, material cycles and energy flow” (Odum, 1971).<br />

In a natural ecosystem like a forest, the vegetation serv<strong>in</strong>g as the energy source for all the animal<br />

k<strong>in</strong>gdom is permanent, evolved over millions <strong>of</strong> years ago, consist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> many plant species and best<br />

suited to the climate. The phytophagous animals <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sects feed<strong>in</strong>g on these plants never <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

beyond certa<strong>in</strong> levels as the natural enemies like parasitoids and predators automatically push down the<br />

phytophagous <strong>in</strong>sect populations. All this is possible beca<strong>use</strong> the vegetation <strong>in</strong> forest ecosystem is<br />

permanent and stable.<br />

If we compare now the <strong>rice</strong> crop as an ecosystem with the forest we can clearly understand the differences.<br />

Here a s<strong>in</strong>gle species that too a s<strong>in</strong>gle variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> is fed with nutrients <strong>of</strong> NPK, Zn etc to serve as a<br />

feast for phytophagous <strong>in</strong>sects and boost their populations. The natural enemies will try to push down the<br />

phytophagous <strong>in</strong>sects but cannot cope up with the tremendous reproductive abilities <strong>of</strong> phytophagous<br />

<strong>in</strong>sects. Hence, natural enemies are present only as passive dependants on phytophagous <strong>in</strong>sects and<br />

cannot actively push down their populations. Further, once the crop is harvested, the natural enemies are<br />

destroyed and hence they have to re-colonize and start multiply<strong>in</strong>g on the phytophagous <strong>in</strong>sects all<br />

afresh. Thus, it is clear why natural biological control alone is not sufficient to push down pest levels <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong><br />

ecosystem.<br />

Thus <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> IPM, the farmer needs to depend on other methods like host-plant resistance where ever<br />

possible, sow and plant <strong>in</strong> time, monitor the pest populations so that they do not cross ETLs, adopt<br />

cultural methods like optimum and recommended fertilizer levels, proper water management, adoption <strong>of</strong><br />

pheromones, botanicals, biopesticides or other non-pesticidal approaches along with need based application<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s.<br />

2

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Pit-falls lie <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g the concept <strong>of</strong> IPM<br />

The difficulties lie <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g how the concept <strong>of</strong> IPM has been evolved. It was thought that the<br />

agro-ecosystems like <strong>rice</strong> need no pesticide application at all or <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest management means / or<br />

synonymous with concept <strong>of</strong> ban on <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> pesticides <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> ecosystems. Therefore, it was stated that<br />

agro ecosystems like <strong>rice</strong> crop needs only to be planted and left to Mother Nature for its care dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

rest <strong>of</strong> the cropp<strong>in</strong>g period. Our past experience proves to the contrary. In many <strong>of</strong> the experiments, it<br />

was observed that even under normal cultural practices with recommended fertilizer levels normal irrigated<br />

<strong>rice</strong> crop suffers very heavily from <strong>in</strong>sect pests like stem borer, gall midge, brown planthopper, whitebacked<br />

planthopper and leaf folder etc. The loss can be between 10 to 25%.<br />

Fertilizer application Versus the Concept <strong>of</strong> IPM<br />

Usually, <strong>rice</strong> farmers <strong>in</strong> deltaic areas apply more than the recommended doses <strong>of</strong> fertilizers, particularly<br />

‘N’. It is this tendency that encourages pest build-up and leads to more pest problems. This practice is<br />

responsible for further enhanc<strong>in</strong>g the magnitude <strong>of</strong> major pests and m<strong>in</strong>or and sporadic pests atta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

major pest status. Therefore, farmers must be advised to strictly follow fertilizer levels based on local<br />

recommendations which depend on the variety, soil type, water management etc. It is collectively called as<br />

“good agronomic practice (GAP). This should form the base and a part <strong>of</strong> IPM.<br />

Host Plant Resistance versus IPM<br />

Integrated pest management is a practical approach <strong>in</strong> which utilization <strong>of</strong> pest resistant varieties is the<br />

key component. But the major limitation <strong>in</strong> full utilization <strong>of</strong> host plant resistance for pest management is<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> suitable resistant sources to major <strong>in</strong>sect pests like stem borer and leaf folder <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>. Good<br />

sources <strong>of</strong> resistance are available <strong>in</strong> case <strong>of</strong> gall midge, but development <strong>of</strong> biotypes is a limitation. But<br />

still gall midge resistant varieties are extensively cultivated <strong>in</strong> many endemic areas, which need no chemical<br />

protection. In case <strong>of</strong> brown planthopper and whitebacked planthopper, the resistance sources are moderate<br />

and also not be<strong>in</strong>g fully exploited. At farmers’ level, the major considerations <strong>in</strong> select<strong>in</strong>g a variety are its<br />

high yield, gra<strong>in</strong> quality, p<strong>rice</strong> <strong>of</strong> the produce and availability <strong>of</strong> market to that particular variety <strong>in</strong> the<br />

region. Host plant resistance at least to major <strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>of</strong> the region <strong>in</strong> a variety is only a secondary<br />

consideration for the farmer. For <strong>in</strong>stance farmers <strong>in</strong> Krishna Godavari Zone <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh and<br />

Tungabhadra Delta <strong>of</strong> Karnataka are grow<strong>in</strong>g only BPT 5204 and Swarna <strong>in</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> the area although<br />

these are susceptible to the major <strong>in</strong>sect pest like brown planthopper <strong>in</strong> these deltas. Similarly, <strong>in</strong> Kerala<br />

red kernel varieties are preferred over white kernel varieties and it is the red kernel varieties that fetch<br />

premium p<strong>rice</strong> to the Kerala farmers <strong>in</strong> the market. Hence, Kerala farmer goes only for red kernel varieties<br />

whether they are resistant or susceptible to brown planthopper, the major menace <strong>in</strong> the state. However,<br />

there are many brown planthopper resistant varieties with white kernel but these did not f<strong>in</strong>d acceptance<br />

with the Kerala farmers.<br />

3

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Biological control versus IPM<br />

There are many species <strong>of</strong> parasitoids and predators for all the major <strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> like stem<br />

borers, planthoppers, leafhoppers, and gall midge etc. Many species <strong>of</strong> spiders present <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem<br />

also prey on these major <strong>in</strong>sect pests. Even when <strong>rice</strong> is sown and planted normally and fertilizer application<br />

is at recommended dose, there are <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> 10-25% <strong>in</strong>festation <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> crop by stem borer and gall<br />

midge <strong>in</strong> endemic areas if the crop is unprotected (DRR, 2006). There are several occasions where<br />

hopper burn has occurred due to planthoppers if timely <strong>in</strong>tervention with <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> application is not<br />

resorted to. Any number <strong>of</strong> examples like this can be cited. The basic question is if the natural biological<br />

control exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> ecosystem is sufficient to keep the <strong>in</strong>sect populations below economic threshold<br />

levels, the occasions described above should not have occurred. This means that human <strong>in</strong>tervention<br />

through <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s is an unavoidable evil to protect <strong>rice</strong> crop from <strong>in</strong>sect pests.<br />

Integrated pest management does not <strong>in</strong>volve only <strong>in</strong>sect pests<br />

IPM <strong>in</strong>volves diseases, weeds, rodents, other <strong>in</strong>vertebrate pests like snails etc. Farmer at his level has to<br />

confront with all these problems <strong>in</strong> adopt<strong>in</strong>g the strategy <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated pest management. The scientists<br />

<strong>in</strong> different discipl<strong>in</strong>es plan and execute the <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong> resistance <strong>in</strong> the varieties concern<strong>in</strong>g their<br />

own discipl<strong>in</strong>es. For <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>in</strong> Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh bacterial leaf blight is a major<br />

menace. Other problems are p<strong>in</strong>k stem borer, yellow stem borer, whitebacked planthopper and leaf folder.<br />

When the whole situation is taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration there are no varieties with good level <strong>of</strong> resistance to<br />

these <strong>in</strong>sect pests. On the other hand, varieties resistant to bacterial leaf blight are available. Another<br />

consideration is that these <strong>in</strong>sect pests can be managed by utiliz<strong>in</strong>g suitable <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>s or other materials.<br />

But there are no effective chemicals so far identified aga<strong>in</strong>st bacterial leaf blight. Therefore, farmers <strong>of</strong><br />

Punjab have to choose necessarily the varieties with bacterial leaf blight resistance. In coastal Andhra<br />

Pradesh and delta areas <strong>of</strong> Karnataka, along with brown planthopper and whitebacked planthopper,<br />

sheath blight is a major menace. But there are no sources <strong>of</strong> resistance to sheath blight <strong>in</strong> the entire <strong>rice</strong><br />

germplasm evaluated so far. The brown planthopper resistant varieties released <strong>in</strong> these areas were<br />

found acceptance with the farmers for some time. But later they have shifted to the susceptible varieties.<br />

Therefore, farmers <strong>in</strong> this area have to manage both brown planthopper and sheath blight together.<br />

Economic thresholds and economic <strong>in</strong>jury levels <strong>in</strong> adoption <strong>of</strong> IPM<br />

As per the def<strong>in</strong>ition “Economic threshold levels are the levels <strong>of</strong> pest population / <strong>in</strong>festation at which<br />

control measures have to be <strong>in</strong>itiated so that the pest population or damage will not reach the economic<br />

<strong>in</strong>jury level”. Economic <strong>in</strong>jury levels have been def<strong>in</strong>ed as the levels <strong>of</strong> pest populations / damage where<br />

the loss <strong>in</strong> economic yield equals to the cost <strong>of</strong> crop protection or cost <strong>of</strong> management options.<br />

There are certa<strong>in</strong> lacunae <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g the concept <strong>of</strong> ETLs <strong>in</strong> pests and diseases on the part <strong>of</strong><br />

many plant protection scientists as well as farmers. ETLs are only broad guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g up control<br />

measures aga<strong>in</strong>st the pest or pests or diseases <strong>in</strong> a given area and given situation. For <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong> brown<br />

4

The follow<strong>in</strong>g are the Economic Threshold Levels for major <strong>in</strong>sect pests<br />

Insect pest Economic thresholds<br />

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Brown planthopper/ 10 <strong>in</strong>sects per hill at vegetative stage or 20 <strong>in</strong>sects per at later<br />

whitebacked planthopper stages<br />

Stem borer 5-10% dead hearts or 1 egg mass / sq m or 1 adult moth / sq. m.<br />

Leaf folder 3 freshly damaged leaves / hill at post active tiller<strong>in</strong>g stage<br />

Green leafhopper 2 <strong>in</strong>sects / hill <strong>in</strong> tungro endemic areas. 20-30 <strong>in</strong>sects /hill <strong>in</strong> other<br />

areas.<br />

Gundhi bug 1 nymph or adult / hill<br />

Gall midge 5% silver shoots at the active tiller<strong>in</strong>g stage<br />

planthopper endemic areas where whitebacked planthopper is also present the population <strong>of</strong> both the<br />

planthoppers is to be taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration while decid<strong>in</strong>g 15 to 20 <strong>in</strong>sects / hill as ETL. In these areas<br />

if the leaf folder is also a major menace, even if the <strong>in</strong>tensity <strong>of</strong> all the pests is below economic threshold<br />

<strong>in</strong> respect <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual pests as cited above, the control measures have to be <strong>in</strong>itiated early. Similarly, <strong>in</strong><br />

areas where brown planthopper and whitebacked planthopper are problems, sheath blight is also a major<br />

menace, the level <strong>of</strong> damage by sheath blight is also to be considered while <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g necessary management<br />

practices.<br />

Another important consideration while decid<strong>in</strong>g the ETL is the stage <strong>of</strong> the plant. Usually, for the <strong>in</strong>cidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> yellow stem borer <strong>in</strong> vegetative stage, 5% dead hearts is considered as ETL. However, at head<strong>in</strong>g<br />

stage, there is no level <strong>of</strong> white ear heads fixed as ETL beca<strong>use</strong> the damage at this stage is not compensated.<br />

Hence, as per the guide l<strong>in</strong>es one moth or 1 egg mass per sq. m. dur<strong>in</strong>g flower<strong>in</strong>g phase or even slightly<br />

earlier has to be considered as ETL. Further, to prevent the white ear head damage, the management<br />

measures have to be <strong>in</strong>itiated before panicle emergence itself. Similarly, <strong>in</strong> case <strong>of</strong> neck blast <strong>in</strong>festation<br />

also, more or less similar guidel<strong>in</strong>es have to be followed.<br />

5

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

BIO-ECOLOGY OF MAJOR INSECT PESTS OF RICE<br />

Rice is cultivated <strong>in</strong> varied environments like uplands, deep-water, shallow-low lands and irrigated conditions.<br />

However, the most preferred ecology <strong>of</strong> the <strong>rice</strong> plant is tropical and humid climate with a temperature<br />

range <strong>of</strong> 15-35 0 C and RH <strong>of</strong> 85-100%. This climate is also best suited for the survival and multiplication<br />

<strong>of</strong> many <strong>in</strong>sects. Therefore, a large number <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sects got adapted for feed<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>rice</strong> and utilize it as their<br />

food. There are more than 100 <strong>in</strong>sect species recorded as feed<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>rice</strong> plant. About 20-25 <strong>of</strong> them<br />

reached the status <strong>of</strong> pests caus<strong>in</strong>g economic losses under farmers’ field situations. Among them, stem<br />

borers, planthoppers, leafhoppers, leaf folders, gall midge, <strong>rice</strong> hispa, gundi bug, case worm, army<br />

worm, cut worm, mealy bugs and <strong>rice</strong> thrips are the most important <strong>in</strong> India and other countries. A brief<br />

bio-ecology <strong>of</strong> these pests is presented below.<br />

Stem borers<br />

The stem borers attack <strong>rice</strong> crop throughout the growth period from nursery up to harvest. The damage<br />

results <strong>in</strong> characteristic symptoms <strong>of</strong> ‘dead hearts’ or ‘white ears’ depend<strong>in</strong>g on the stage <strong>of</strong> the crop.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g vegetative phase, the stem borer larvae emerge from the egg masses laid on leaves and enter the<br />

tiller to feed <strong>in</strong>side, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the characteristic damage <strong>of</strong> ‘dead heart’. In the damaged plants, the<br />

central leaf whorl does not unfold, turns brownish and dries out although the lower leaves rema<strong>in</strong> green<br />

and healthy. The affected tillers do not grow further and eventually dry. The dead heart comes out easily<br />

6<br />

YSB Male YSBFemale YSB Egg mass<br />

YSB Pupa<br />

YSB Larva

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

when pulled and emits foul smell. At reproductive stage, the damage is characterized by whitish, erect<br />

and chaffy panicles, which are very conspicuous <strong>in</strong> field and are called ‘white ears’. However, the stem<br />

borer damage may occur dur<strong>in</strong>g the gra<strong>in</strong> fill<strong>in</strong>g stage also, lead<strong>in</strong>g to stoppage <strong>of</strong> further gra<strong>in</strong> fill<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g partially filled gra<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

There are five species <strong>of</strong> stem borers distributed throughout India. Among these, yellow stem borer (YSB),<br />

Scirpophaga <strong>in</strong>certulas (Walker) is the most important, widespread, dom<strong>in</strong>ant and destructive. The other<br />

borers are, p<strong>in</strong>k stem borer, Sesamia <strong>in</strong>ferens (Walker) occurr<strong>in</strong>g mostly <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>-wheat cropp<strong>in</strong>g systems<br />

<strong>of</strong> north-west, white borer, Scirpophaga <strong>in</strong>notata (Walker) common <strong>in</strong> southern region particularly <strong>in</strong><br />

Kerala, dark headed stem borer, Chilo polychrysus (Meyrick) and striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis<br />

(Meyrick) <strong>in</strong> states <strong>of</strong> West Bengal and Assam respectively.<br />

In southern parts <strong>of</strong> India where <strong>rice</strong> is cultivated through out the year, there are usually 3 generations<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g kharif season and 2 generations dur<strong>in</strong>g rabi season. Similar is the case <strong>in</strong> most parts <strong>of</strong> eastern<br />

states like Orissa, West Bengal and the north eastern states like Assam, etc. However, <strong>in</strong> north western<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> India, where one crop season <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> is prevail<strong>in</strong>g, the yellow stem borer completes 2-3 generations<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g kharif and enters <strong>in</strong>to quiescent stage or diapa<strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> larval stage dur<strong>in</strong>g October-November<br />

immediately after <strong>rice</strong> is harvested. It rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> that stage through out the w<strong>in</strong>ter months <strong>of</strong> December to<br />

February-March. With rise <strong>in</strong> the temperatures dur<strong>in</strong>g March, the diapa<strong>use</strong> is broken, the larva pupates<br />

and emerges as adult from April beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g on wards.<br />

Brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stal.)<br />

Brown planthopper emerged as a major pest <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> <strong>in</strong> India only after 1972, when large scale adoption <strong>of</strong><br />

short-statured high yield<strong>in</strong>g and high nitrogen responsive varieties occupied major areas <strong>in</strong> deltas <strong>of</strong> A.P.,<br />

BPH Adults BPH Eggs<br />

BPH Nymphs BPH Damage<br />

7

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka, although this pest was notorious <strong>in</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Japan, North and<br />

South Koreas even dur<strong>in</strong>g early parts <strong>of</strong> 20 th century. In those countries japonicas were traditionally<br />

grown with high fertilizer levels. The microclimate <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> crop which existed <strong>in</strong> japonica varieties <strong>in</strong> those<br />

countries also started prevail<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> India, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, Indonesia etc. which are tropical countries, after<br />

large scale adoption <strong>of</strong> dwarf varieties. Although the microclimate <strong>in</strong> these tropical countries is not precisely<br />

del<strong>in</strong>eated, shady atmosphere, high humidity, improper aeration, coupled with optimum temperature <strong>of</strong><br />

25-30 0 C appear to be responsible for rapid build up <strong>of</strong> BPH caus<strong>in</strong>g heavy losses. Heavy nitrogen<br />

application associated with dwarf varieties also appeared to be responsible for major BPH epidemics <strong>in</strong><br />

tropical countries.<br />

Adult BPH are dimorphic. W<strong>in</strong>ged as well as half w<strong>in</strong>ged males and females along with nymphs occur as<br />

mixed populations <strong>in</strong> fields. Both adults and nymphs suck sap from the base <strong>of</strong> the tillers, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

yellow<strong>in</strong>g and dry<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the plants. At early stages <strong>of</strong> attack, round yellowish patches appear which soon<br />

turn brownish due to dry<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>of</strong> the plants. The patches <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>festation spread <strong>in</strong> concentric circles with<strong>in</strong><br />

the field and <strong>in</strong> severe cases the affected field gives a burnt appearance known as ‘hopper burn’. The<br />

hopper populations can multiply very fast and migrate over long distances caus<strong>in</strong>g widespread <strong>in</strong>festation<br />

<strong>in</strong> short time. Apart from caus<strong>in</strong>g direct damage, BPH also acts as a vector <strong>of</strong> grassy stunt virus.<br />

The life cycle <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>sect is completed with<strong>in</strong> 20-25 days depend<strong>in</strong>g on temperature. There are usually<br />

3-4 overlapp<strong>in</strong>g generations dur<strong>in</strong>g the crop season. The w<strong>in</strong>ged adults settle <strong>in</strong> the crop after 15-20<br />

days <strong>of</strong> transplant<strong>in</strong>g. But the population will be very low. It is <strong>of</strong> the order <strong>of</strong> 2-5 <strong>in</strong>sects per 100 hills.<br />

Hence, farmer cannot recognize its presence. It is only dur<strong>in</strong>g 3rd or 4th generation we can see the<br />

population <strong>in</strong> damag<strong>in</strong>g proportions. By that time, the crop comes to flower<strong>in</strong>g phase. That is the reason<br />

why farmers th<strong>in</strong>k that BPH attacks <strong>rice</strong> crop only at flower<strong>in</strong>g phase (Krishnaiah et al., 2006b).<br />

Whitebacked planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Horvath)<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g 70s and 80s whitebacked planthopper (WBPH) <strong>use</strong>d to be conf<strong>in</strong>ed to north-western belt <strong>of</strong><br />

Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh. Later, the pest has spread to almost all areas where <strong>rice</strong> is<br />

grown and started occurr<strong>in</strong>g together with BPH <strong>in</strong> many deltas <strong>of</strong> the southern states. This has emerged<br />

as a serious pest <strong>in</strong> areas particularly where <strong>rice</strong> varieties resistant to BPH are grown. The partially<br />

8<br />

WBPH Adults WBPH Eggs WBPH Nymphs

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

cleared ecological- niche due to low population <strong>of</strong> BPH on resistant varieties appeared to have triggered<br />

the multiplication <strong>of</strong> WBPH on those varieties.<br />

WBPH is relatively smaller <strong>in</strong> size compared to BPH with a conspicuous white spot on dorsal thorax. Hence, the<br />

name whitebacked planthopper. The nature <strong>of</strong> damage and the biology <strong>of</strong> WBPH are similar to BPH. Both<br />

nymphs and adults suck the plant sap from phloem and ca<strong>use</strong> dry<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>of</strong> plants. Unlike BPH, it does not ca<strong>use</strong><br />

sudden and severe hopper burn. WBPH is not known to transmit any <strong>of</strong> the virus diseases <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong>.<br />

The ecological conditions like high humidity (90 to 100%), optimum temperature (22 – 27oC) is very similar to<br />

BPH. The most significant difference between BPH and WBPH is that WBPH tends to be more numerous dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

early stages <strong>of</strong> crop growth i.e. up to 40 DAT, while BPH multiplies faster later on. In many <strong>of</strong> the deltaic areas<br />

WBPH is conf<strong>in</strong>ed mostly to kharif season while BPH occurs dur<strong>in</strong>g both kharif and rabi seasons.<br />

Green leafhoppers Nephotettix virescens (Distant) and Nephotettix nigropictus (Stal)<br />

There are two species <strong>of</strong> green leafhopper occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> viz., Nephotettix virescens (Distant) and Nephotettix<br />

nigropictus (Stal). Both the leafhoppers suck the sap from <strong>rice</strong> plant from phloem as well as xylem. But unlike<br />

planthoppers, green leafhoppers do not ca<strong>use</strong> hopper burn. These two <strong>in</strong>sects are economically important as<br />

vectors <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> tungro disease (RTD). They transmit RTD from one plant to another and act as vectors <strong>of</strong> the<br />

GLH Adults GLH Eggs GLH Nymphs<br />

disease. Rice is the ma<strong>in</strong> host for N. virescens although it can feed on some grassy weeds occurr<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>rice</strong><br />

bunds. N. nigropictus feeds ma<strong>in</strong>ly on Leersia hexandra and other weed hosts and occasionally feeds on <strong>rice</strong><br />

crop. RTD is transmitted from weed hosts to <strong>rice</strong> crop ma<strong>in</strong>ly through N. nigropictus while the transmission<br />

among the <strong>rice</strong> plants is ma<strong>in</strong>ly by N. virescens. GLH lay their eggs either <strong>in</strong> the mid rib <strong>of</strong> leaves or <strong>in</strong> leaf sheath.<br />

The nymphs <strong>of</strong> N. nigropictus are brownish to p<strong>in</strong>kish <strong>in</strong> colour while the nymphs <strong>of</strong> N. virescens are light green<br />

<strong>in</strong> colour. N. nigropictus has a conspicuous black spot on the head, which is absent <strong>in</strong> case <strong>of</strong> N. virescens.<br />

The optimum conditions for multiplication <strong>of</strong> N. virescens and N. nigropictus are about 25 o C temperature and<br />

80% RH. Both the <strong>in</strong>sects are more numerous dur<strong>in</strong>g September and October months <strong>of</strong> kharif. Another GLH<br />

species called N. c<strong>in</strong>ticeps (Uhler) is present <strong>in</strong> Japan and Korea and it is not prevalent <strong>in</strong> India.<br />

9

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Gundhi bugs Leptocorisa acuta (Thunberg) and Leptocorisa oratorius (Fabricius)<br />

There are ma<strong>in</strong>ly two species <strong>of</strong> gundhi bug viz., Leptocorisa acuta (Thunberg) and<br />

Leptocorisa oratorius. The nymphs as well as adults emit a characteristic <strong>of</strong>fensive<br />

odour <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fested fields, which can be very easily recognized as a signal <strong>of</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> gundhi bug <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> fields. The nymphs and adults feed on develop<strong>in</strong>g milky gra<strong>in</strong>s<br />

caus<strong>in</strong>g brown spots and results <strong>in</strong> damag<strong>in</strong>g the quality <strong>of</strong> the gra<strong>in</strong>. At times, it<br />

becomes more serious and can ca<strong>use</strong> heavy losses. The eggs are laid <strong>in</strong> rows on<br />

upper or lower side <strong>of</strong> leaves. There are five nymphal <strong>in</strong>stars, which last for 25 to 30<br />

days.<br />

Leaf folder Cnaphalocrocis med<strong>in</strong>alis (Guenee)<br />

There are six to eight species <strong>of</strong> leaf folders attack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>rice</strong> crop but the most important one is Cnaphalocrocis<br />

med<strong>in</strong>alis (Guenee). As the very name <strong>in</strong>dicates the larvae, after emerg<strong>in</strong>g from eggs, fold the leaves with the<br />

10<br />

LF Female LF Male LF Eggs<br />

LF Larva LF Damage<br />

Gundhi Bug Adult<br />

help <strong>of</strong> silken threads secreted from salivary glands, rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>side and feed on the chlorophyll content <strong>of</strong> the<br />

leaves leav<strong>in</strong>g only the lower epidermis. As a result, the photosynthetic activity is affected result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> loss <strong>of</strong><br />

gra<strong>in</strong> yield. The loss <strong>in</strong> yield is more significant when larvae feed on boot-leaf compared to other lower leaves.<br />

There are 5 larval <strong>in</strong>stars, which are completed <strong>in</strong> 18 to 25 days depend<strong>in</strong>g on the temperatures. The pupation

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

occurs <strong>in</strong>side the folded leaf, and the pupal period lasts for 5 to 7 days. The adult emerges and after mat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

starts lay<strong>in</strong>g eggs s<strong>in</strong>gly or <strong>in</strong> groups <strong>of</strong> 2-3 either on the lower side or upper side <strong>of</strong> the leaf or sometimes on<br />

leaf sheath. The egg period lasts for 4-6 days. The population <strong>of</strong> leaf folder, <strong>in</strong>creases tremendously at higher<br />

nitrogen levels. As farmer tends to apply more than recommended nitrogen, leaf folder is becom<strong>in</strong>g more<br />

serious <strong>in</strong> many <strong>of</strong> the irrigated <strong>rice</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g deltaic tracts <strong>in</strong> many states. Of late, the population <strong>of</strong> leaf folder<br />

is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> plots treated with either phorate or carb<strong>of</strong>uran granules.<br />

Gall midge Orseolia oryzae (Wood Mason)<br />

The maggot <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> gall midge enters <strong>in</strong>side the young <strong>rice</strong> plant and starts feed<strong>in</strong>g on grow<strong>in</strong>g portions. As a<br />

result, the meristematic tissue grows and encloses the feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sect <strong>in</strong>side. The meristematic tissue as it grows,<br />

turns <strong>in</strong>to a pale green tubular structure called “silver shoot.” The larvae pupates <strong>in</strong>side the silver shoot and<br />

emerges as adult from the top portion <strong>of</strong> silver shoot. The damaged tiller does not bear panicle. The crop under<br />

severe <strong>in</strong>festation is stunted with more numerous tillers. These new tillers are also eventually attacked result<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> almost 80 to 90% loss under severe <strong>in</strong>festation conditions.<br />

GM Adult GM Eggs GM Larva<br />

GM Pupa GM Damage<br />

The damage is more serious dur<strong>in</strong>g kharif or wet season, although, gall midge started <strong>in</strong>fest<strong>in</strong>g rabi <strong>rice</strong> also <strong>in</strong><br />

some <strong>of</strong> the coastal <strong>rice</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g tracts. For proper egg hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> gall midge, 90 to 100% humidity is<br />

essential. High humidity and a th<strong>in</strong> film <strong>of</strong> water are required for larval dispersal and entry <strong>in</strong>to the plant. The<br />

female adult is a mosquito like dipteran fly with reddish abdomen. The male is slightly smaller <strong>in</strong> size with<br />

11

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

brownish abdomen. The adult life span is one to four days. The mat<strong>in</strong>g occurs immediately after emergence and<br />

eggs are laid any where on the foliage. The eggs are microscopic, cigar shaped and the egg period is about<br />

three to four days. There are five larval <strong>in</strong>stars, which last for twelve to fifteen days. The optimum temperature<br />

for <strong>rice</strong> gall midge is 22 to 26 oC. Gall midge is more severe, <strong>in</strong> late planted conditions.<br />

Although a number <strong>of</strong> gall midge resistant varieties are released, their spread is hampered due to the<br />

problem <strong>of</strong> biotypes.<br />

Rice hispa Dicladispa armigera Olivier<br />

The adults <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> hispa (Dicladispa armigera Olivier) are sh<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g black beetles<br />

with sp<strong>in</strong>es on forew<strong>in</strong>gs. Both adults and grubs damage the crop. The adults<br />

scrap the chlorophyll content on the upper side and lower side <strong>of</strong> leaves. The<br />

grubs m<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> between two epidermal layers and feed on the chlorophyll content.<br />

In severe <strong>in</strong>festations, the crop gets dried with whitish appearance without any<br />

green colour. In cases <strong>of</strong> epidemics, about 25- 50 beetles may be present on a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle hill. This pest is more serious <strong>in</strong> young stages <strong>of</strong> the crop growth either <strong>in</strong><br />

nursery or <strong>in</strong> early transplanted conditions.<br />

Hispa Adult<br />

The adult beetles lay eggs s<strong>in</strong>gly either on the lower surface or on the upper surface <strong>of</strong> leaves covered<br />

with a brownish material. The egg period is about six to seven days. The emerg<strong>in</strong>g grubs directly enter<br />

between the two epidermal layers and grow there. The total larval period (five <strong>in</strong>stars) lasts for 15 –18<br />

days. The pupation occurs <strong>in</strong> the larval m<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> between the two epidermal layers and the pupal period<br />

lasts for 4 to 5 days.<br />

Hispa <strong>use</strong>d to be a sporadic pest previously. However, it is occurr<strong>in</strong>g regularly <strong>in</strong> many Sub-Himalayan<br />

areas and also <strong>in</strong> north-eastern states.<br />

Case worm Adult<br />

12<br />

Case worm Nymphula depunctalis (Guenee)<br />

Case worm Nymphula depunctalis (Guenee) is a sporadic pest and occurs usually<br />

<strong>in</strong> young crop located <strong>in</strong> stagnant water. The attack is usually patchy and not<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous. The larva cuts the leaves <strong>in</strong>to small bits and makes them <strong>in</strong>to cases<br />

<strong>of</strong> approximately its own body size.The larvae rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>side the case and feeds<br />

on leaves, by scrapp<strong>in</strong>g the chlorophyll content. As a result, the plant growth<br />

and vigour are seriously affected. If the leaves are disturbed, the cases along<br />

with larvae fall on water surface. This is the characteristic symptom <strong>of</strong> case<br />

worm attack. The larva is aquatic and can breathe with gills.

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Cut worms Mythimna separata (Walker) and army worms Spodoptera mauritia (Boisd.)<br />

These are a group <strong>of</strong> noctuid pests occurr<strong>in</strong>g sporadically <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong>. The most<br />

important among these <strong>in</strong>sects are (1) the army worm Spodoptera mauritia<br />

and the cut worm Mythimna separata. The former is a gregarious pest. It<br />

<strong>use</strong>d to ca<strong>use</strong> severe losses to <strong>rice</strong> crop before the green revolution era.<br />

This pest moves from one field to another field <strong>in</strong> large numbers like an army<br />

Cut worm Larva<br />

and almost completely defoliates the <strong>rice</strong> crop <strong>in</strong> the fields they <strong>in</strong>vade. Hence,<br />

the name army worm. Cut worms, at times become serious and feed on the foliage dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itial stages <strong>of</strong><br />

crop growth. After flower<strong>in</strong>g, the larvae climb and cut the ear-heads result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the entire ear<br />

head or a part <strong>of</strong> the ear-head. This results <strong>in</strong> very serious losses to the crop. The <strong>in</strong>festation may occur<br />

just before harvest lead<strong>in</strong>g to fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> even matured gra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> huge quantities.<br />

Mealy bug Brevennia rehi (L<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ger)<br />

Mealy bug damage & adult (<strong>in</strong>set)<br />

Rice thrips Stenchaetothrips biformis (Bagnall)<br />

Mealy bug is a common pest <strong>in</strong> upland and dry areas and <strong>in</strong> fields with<br />

uneven surface and where plant stand is not uniform and patchy.<br />

These mealy bugs are covered by a dist<strong>in</strong>ct waxy and powdery coat<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Ants frequently visit the mealy bug <strong>in</strong>fested plants and help <strong>in</strong> the<br />

dispersal <strong>of</strong> bugs from one plant to another. Both the adults and<br />

nymphs suck the plant sap result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the stunted growth and curved<br />

yellowish leaves. In severe <strong>in</strong>festations, plants dry up and panicles do<br />

not emerge from the boot leaf. Damage occurs <strong>in</strong> patches and is<br />

severe under moisture stress conditions.<br />

Rice thrips (S. biformis) occur dur<strong>in</strong>g the seedl<strong>in</strong>g stage and <strong>in</strong> early transplanted crop. The nymphs and<br />

adults suck the sap from the leaves. Due to this feed<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>itially yellow streaks appear on the leaves and<br />

Thrips Thrips Damage<br />

13

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

later they curl longitud<strong>in</strong>ally from the marg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>wards. These have sharp po<strong>in</strong>ted leaf tips resembl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

needles, which f<strong>in</strong>ally dry up. The plants become lanky and present a sick appearance.<br />

Black bug Scot<strong>in</strong>ophara sp.<br />

Black bug or Malayan bug is a common name for a group <strong>of</strong> Pentatomids belong<strong>in</strong>g to the genus<br />

Scot<strong>in</strong>ophara. Three species namely, S. coarctata (Fabricius), S. lurida (Burmeister) and S. bisp<strong>in</strong>osa<br />

(Fabricius) were found <strong>in</strong> India. Both nymphs and adults suck sap from the base <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> stems and <strong>in</strong>fest<br />

<strong>rice</strong> plants from seedl<strong>in</strong>g to flower<strong>in</strong>g stage. Adults are black <strong>in</strong> colour and can live up to seven months.<br />

Female lays about 200 eggs at the basal portion <strong>of</strong> the <strong>rice</strong> plant near the water surface. Freshly laid<br />

eggs are green <strong>in</strong> clour and turn p<strong>in</strong>k before hatch<strong>in</strong>g. Egg period lasts for about 4-7 days. Nymphs are<br />

light brown with yellowish green abdomen. They pass through four to five <strong>in</strong>stars <strong>in</strong> about 25- 30 days.<br />

The bugs aestivates <strong>in</strong> cracks <strong>of</strong> bunds <strong>in</strong> the adult or late nymphal stage.<br />

Leaf mite Oligonychus oryzae (Hirst)<br />

Leaf mites feed on upper and lower surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> leaves. Usually they are more numerous on lower<br />

surface than upper surface. Leaf mites are small and microscopic spider mites which pierce the leaf<br />

tissue and suck the exud<strong>in</strong>g sap. They multiply very fast under congenial condition and damage the entire<br />

14<br />

Mites Mite damage<br />

leaf portion under severe <strong>in</strong>festation. The damage results <strong>in</strong> the appearance <strong>of</strong> yellowish brown specks<br />

which <strong>in</strong>crease under severe conditions and whole leaf turns to brown with complete loss <strong>of</strong> chlorophyll.<br />

The secretions <strong>of</strong> leaf mites form m<strong>in</strong>ute webs on the damaged surface <strong>of</strong> the leaf. These complete life<br />

cycle <strong>in</strong> 10-12 days.<br />

The damage is most serious dur<strong>in</strong>g summer months when the temperature is high and humidity is low<br />

compared to w<strong>in</strong>ter and ra<strong>in</strong>y seasons.<br />

Panicle mite Steneotarsonemus sp<strong>in</strong>kii Smiley<br />

Sheath mite or panicle mite is transparent, microscopic tarsonemid mite which is mostly conf<strong>in</strong>ed to<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal tissues. Sheath mite attacks <strong>rice</strong> at panicle <strong>in</strong>itiation stage and conf<strong>in</strong>es to the area between leaf

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

sheath and the stem. With the development <strong>of</strong> panicle <strong>in</strong>side the boot, sheath mite moves to the panicle<br />

and starts damag<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternal tissues <strong>of</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g gra<strong>in</strong>s. As a result the gra<strong>in</strong>s become sterile and<br />

ill-filled. In association with the sheath rot fungus, Acrocyl<strong>in</strong>drium oryzae, sheath mite or panicle mite<br />

ca<strong>use</strong>s brown discolouration even <strong>in</strong> fully developed gra<strong>in</strong>s. This leads to deterioration <strong>in</strong> paddy gra<strong>in</strong><br />

quality.<br />

Before sheath mite enters <strong>in</strong>to develop<strong>in</strong>g gra<strong>in</strong>s, it is also present on midrib <strong>of</strong> leaf sheath and leaf and<br />

ca<strong>use</strong>s brownish, longitud<strong>in</strong>al specks. It completes life cycle <strong>in</strong> 10 days.<br />

15

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

ORGANOPHOSPATES<br />

16<br />

INSECTICIDES USED IN RICE PEST<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>alphos: C H N O PS. O, O-diethyl O-qu<strong>in</strong>oxal<strong>in</strong>e-2-yl phosporothioate. It is a contact and stomach<br />

12 15 2 3<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> and acaricide with good penetrative properties. It is effective aga<strong>in</strong>st suck<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sects and<br />

lepidopterous larvae particularly <strong>of</strong> cotton and <strong>rice</strong>. The acute oral LD and dermal LD for rats are 62-<br />

50 50<br />

137 mg/kg and 1250-1400 mg/kg respectively. It is toxic to honeybees. It is formulated as 25% EC, 5%<br />

granules and 1.5% dust.<br />

Phosalone: C H CINO PS . It is O, O-diethyl S- (6-chloro 1, 3 benzoxazole-2 (3H)-on-methyl)<br />

12 15 4 2<br />

phosphorodithioate or 3-O,-O, diethyl dithiophosphorylmethyl-6 chloro benzoxazolone. It is a contact<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> and acaricide effective aga<strong>in</strong>st a wide range <strong>of</strong> pest species. It is stable under normal storage<br />

conditions, compatible with most other pesticides and non-corrosive. It is safe to honey bees and natural<br />

enemies <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sect pests. Formulated as 4% dust and 35% EC. LD for rat: oral 120-170mg/kg, dermal<br />

50<br />

1500 mg/kg.<br />

Monocrotophos: C H NO P. It is dimethyl (E)-1-methyl-2-methylcarbamoylv<strong>in</strong>yl posphate. It is <strong>in</strong>compatible<br />

7 14 5<br />

with alkal<strong>in</strong>e pesticides. It is corrosive to iron, brass and drum steel. It is a fast act<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> and<br />

acaricide with both systemic and contact action <strong>use</strong>d aga<strong>in</strong>st a wide range <strong>of</strong> pests <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g mites,<br />

suck<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sects, leaf eat<strong>in</strong>g beetles and bollworms. It persists for 7-14 days. It is highly toxic to birds and<br />

honeybees. Oral LD for rats is 14-23 mg/kg and dermal LD for rabbit is 336 mg/kg. Formulated as<br />

50 50<br />

36% SL.<br />

Chlorpyriphos: C H C NO PS. The chemical name is O,O-diethyl O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl)<br />

9 11 l3 3<br />

phosphorothioate. It is compatible with non-alkal<strong>in</strong>e pesticides but corrosive to copper and brass. It has<br />

a broad range <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>secticidal activity and <strong>use</strong>d for the control <strong>of</strong> mosquitoes, flies, soil and foliar crop<br />

pests, ho<strong>use</strong>hold pests and animal pests. It is contact, non-systemic and has some fumigant action. It is<br />

non-phytotoxic and persists <strong>in</strong> the soil for 60-120 days. It is toxic to fish and shrimps. It is rapidly detoxified<br />

<strong>in</strong> the animal body. The acute oral LD for rats is 135-163 mg/kg. The formulations registered are 20%<br />

50<br />

EC, 10% granules and 1.5% DP.<br />

Acephate: C H NO PS. It is O, S-dimethyl acetylphosphoramideothioate. Acephate is a contact and systemic<br />

4 10 3<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> with moderate persistence for 10-15 days and effective aga<strong>in</strong>st aphids, thrips, leaf m<strong>in</strong>ers,<br />

saw flies and lepidopterous larvae. It is formulated as 75% SP. Acute oral LD for rats is 866-945 mg/kg;<br />

50<br />

dermal for rabbit is >2000 mg/kg. It is relatively safer to many natural enemies compared to other<br />

organophosphates.<br />

Fenitrothion: C 9 H 12 O 5 NPS. It is O, O-dimethyl O- (3-methyl -4 nitrophenyl) phosphorothioate. It is a contact<br />

and stomach <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>, selective acaricide but <strong>of</strong> low ovicidal activity. It is toxic to bees and fish. It is a<br />

broad-spectrum <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong>d for the control <strong>of</strong> mites, mosquito larvae, bed bugs, poultry lice,

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

ectoparasites <strong>of</strong> livestock and pet animals. Formulations registered are 5% DP, 40% WP, 50% EC, 5% G,<br />

2% spray, 20% OL. Oral LD for rats is 250 mg/kg and dermal for mice is > 3000 mg/kg.<br />

50<br />

Dichlorvos (DDVP): C H C1 O P. It is 2,2-dichlorov<strong>in</strong>yl dimethyl phosphate. It is a contact and stomach<br />

4 7 2 4<br />

poison with fumigant and penetrant action. It br<strong>in</strong>gs quick knock down effect. It is moderately toxic<br />

to fish but highly toxic to bees. Soon after application <strong>in</strong> leaves it gets hydrolyzed to harmless<br />

dimethyl phosphoric acid and dichloroacetaldehyde, which decomposes and evaporates. Therefore,<br />

it does not leave any residue and can be <strong>use</strong>d on all crops until shortly before harvest. It is <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the<br />

control <strong>of</strong> ho<strong>use</strong>hold pests lepidopterous larvae, suck<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sects etc. It is available <strong>in</strong> India as 76% SC.<br />

Oral LD for alb<strong>in</strong>o male rat 80 mg/kg, for female 56 mg/kg; dermal-alb<strong>in</strong>o male rat 107 g/kg, and<br />

50<br />

female rat 75 mg/kg.<br />

Fenthion: C H O PS . It is O, O-dimethyl, O-3 me-thyl-4-methylthiophenyl phosphorothionate. It is a<br />

10 15 3 2<br />

systemic and contact <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> with high persistence. In the plant it is oxidized to sulfoxide and sulfone,<br />

which are <strong>in</strong>secticidally active. It is harmful to bees. It is effective aga<strong>in</strong>st a wide variety <strong>of</strong> pests<br />

particularly fruit flies, mango nut weevil, etc. Registered formulations are 82.5 EC, 2% G and 2% spray.<br />

LD for rat: oral 215-245 mg/kg; dermal 320-330 mg/kg.<br />

50<br />

Phorate: C H O PS . It is O,O-diethyl S-(ethylthio- methyl) phosphorothiolothionate. It is a systemic<br />

7 17 2 8<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>use</strong>d for soil application as granules. It has contact and fumigant action and to<br />

some extent nematicidal and acaricidal action also. It does not persist for a longer period and gets<br />

metabolically oxidized yield<strong>in</strong>g phosphorothioate and sulfone, which are readily hydrolysed. It has<br />

been found effective aga<strong>in</strong>st sorghum shoot fly and <strong>rice</strong> gall midge. Formulated as 10% G. LD for 50<br />

rat: oral 16 to 37, dermal 2.5 to 6.2 mg/kg.<br />

Phosphamidon: C H O NCIP. It is 2 - Chloro - 2 – diethyl carbamoyl – 1 - methyl v<strong>in</strong>yl dimethyl<br />

10 19 5<br />

phosphate.It is a systemic poison and has relatively less contact action. It is relatively less toxic to<br />

fish but toxic to bees. Useful <strong>in</strong> the control <strong>of</strong> suck<strong>in</strong>g pests, leaf m<strong>in</strong>ers, certa<strong>in</strong> mites etc. Though<br />

compatible with most pesticides, its biological activity is reduced with copper oxychloride. LD for rat:<br />

50<br />

Oral 17.9 - 30 mg/kg, dermal 374 - 530 mg/kg. Its <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> India is be<strong>in</strong>g phased out.<br />

Ethoprophos: C H O PS It is O-ethyl S.S-dipropyl phosphorodithioate. It is an ether derivative. It is very<br />

8 19 2 2.<br />

stable <strong>in</strong> water up to 100° but is rapidly hydrolysed <strong>in</strong> alkal<strong>in</strong>e media at 25°. Ethoprophos is a nonsystemic,<br />

non-fumigant nematicide and soil <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong>d at rates <strong>of</strong> 1.0 kg a.i./ha for most crops. The<br />

acute oral LD for alb<strong>in</strong>o rats is 62 mg/kg; the acute dermal LD for alb<strong>in</strong>o rabbits is 26mg/kg. It is<br />

50 50<br />

formulated as granules and EC.<br />

CARBAMATES<br />

Carbaryl: C |2 H H NO 2 It is 1 - napthyl N - methyl carbamate. It was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> 1956. It is a contact<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> with slight systemic action. It is not generally phytotoxic up to 2 kg a.i./ha and is compatible<br />

with most pesticides except Bordeaux mixture, lime sulphur and urea. It is effective aga<strong>in</strong>st a wide<br />

spectrum <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sect pests <strong>of</strong> crops particularly <strong>of</strong> cotton. It does not kill mites. Application <strong>of</strong> carbaryl<br />

17

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

on apple trees ca<strong>use</strong>s fall <strong>of</strong> young fruits. It is formulated as 5% or 10% dust, 4% granule and<br />

50% WP or 85% SP or 40% LV and 42% Flow. 5% dust controls ticks on cattle, sheep and dogs and<br />

poultry lice. Sevidol granule recommended for control <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> pests is composed <strong>of</strong> 4% <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong><br />

carbaryl and gamma HCH. Sevimol 40 LV is a product conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 40% carbaryl plus molasses.<br />

Carb<strong>of</strong>uran: C H NO . It is 2,3-dihydro - 2, 2-dimethyl 7 benz<strong>of</strong>uranyl methyl carbamate. It is a<br />

I2 15 3<br />

systemic <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> and nematicide effective aga<strong>in</strong>st suck<strong>in</strong>g and soil <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g pests and <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong><br />

the control <strong>of</strong> sorghum shoot fly. Established crop tolerances are: 0.5 ppm <strong>in</strong> forage, 0.1 ppm <strong>in</strong> gra<strong>in</strong>;<br />

0.2 ppm <strong>in</strong> <strong>rice</strong> and <strong>rice</strong> straw. Formulated as 50% SP and 3% granule. LD for rat: oral 8.8 to 14.1<br />

50<br />

mg/kg; dermal 10,200 mg/kg. Carb<strong>of</strong>uran application <strong>in</strong>duced growth stimulation <strong>in</strong> cotton, <strong>rice</strong>,<br />

tobacco, sorghum and corn.<br />

Carbosulfan: C H N O S. It is 2, 3 - dihydro - 2, 2 - dimethyl benz<strong>of</strong>uran - 7 - yl (dibutylam<strong>in</strong>othio) -<br />

20 22 2 3<br />

methyl carbamate. It is effective aga<strong>in</strong>st a broad spectrum <strong>of</strong> pest species on various crops. It is<br />

metabolized <strong>in</strong> plants to carb<strong>of</strong>uran and 3 -hydroxycarb<strong>of</strong>uran. Its registered formulations are 25% DS<br />

and 25% EC. Its acute oral LD5 for rat 185 - 250 mg/kg; dermal for rat > 2000 mg/kg.<br />

0<br />

BPMC or Fenobucarb: C H NO . It is 2-jec-butylphenyl methyl-carbamate. It is unstable to alkali and to<br />

12 17 2<br />

concentrated acid. It is an <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>use</strong>d to control hoppers on <strong>rice</strong>. The acute oral LD is: 410 mg/kg<br />

50<br />

for rats; dermal LD for mice is 4200 mg/kg. It is formulated as EC, dust and granules.<br />

50<br />

MIPC or Isoprocarb: C H NO . It is 2-isopropylphenyl methylcarbamate or o- cumenyl methylcarbamate. It<br />

11 15 2<br />

is compatible with most conventional pesticides, but should not be comb<strong>in</strong>ed with products hav<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

alkal<strong>in</strong>e reaction nor <strong>use</strong>d with<strong>in</strong> 10 days prior to or after application <strong>of</strong> propanil. Isoprocarb is a contact<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> <strong>of</strong> low mammalian toxicity effective aga<strong>in</strong>st pests <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong>, for the control <strong>of</strong> aphids, leafhoppers,<br />

capsid bugs and other pests <strong>of</strong> deciduous fruit and other crops. It has a moderately long residual activity.<br />

The acute oral LD is 403-485 mg/kg for rats. The acute dermal LD for male rats is > 500 mg/kg. It<br />

50 50<br />

is harmful to honey bees. The formulations <strong>in</strong>clude wettable powder, EC, thermal fog, granules and dusts.<br />

INSECT GROWTH REGULATOR<br />

Bupr<strong>of</strong>ez<strong>in</strong>: C 16 H 23 N 3 OS. It is 2-tert - butylim<strong>in</strong>o - 3 - isopropyl - 5 - phenylperhydro - 1,3,5 -<br />

thiadiaz<strong>in</strong> -4 - one. It has contact and stomach action. Effective aga<strong>in</strong>st mealy bugs, whiteflies,<br />

scales, plant hoppers, etc. The eggs laid by treated <strong>in</strong>sects are sterile. Oral LD 50 for rat is > 2000<br />

mg/kg; dermal for rat is > 5000 mg/kg.<br />

PHENYL PYRAZOLES<br />

Fipronil: C 12 H 4 C1 2 F 6 N 4 OS. It is chemically (±) -5 -am<strong>in</strong>o - 1 - (2,6 - dichloro -trifluoro - g_ tolyl) - 4<br />

trifluoro methyl) = sulf<strong>in</strong>ylpyrazole - 3 - carbonitrile. It is an <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> and acaricide effective aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

pests <strong>of</strong> <strong>rice</strong> <strong>in</strong> India. Acute oral LD 50 for rat is100 mg/kg, dermal for rat is > 2000 mg/kg. Its<br />

registered formulations <strong>in</strong> India are 0.3% G and 5% SC.<br />

18

Insecticides <strong>in</strong> Rice IPM (DRR)<br />

Ethiprole: C 13 H 9 C 12 F 3 N 4 OS. The chemical name is 5-amono-1-(2-6-dichloro-4-(trifluromethyl)-4ethylsulf<strong>in</strong>yl-1H-pyrazole-3-carbonitrile.<br />

It differs from fipronil the major phenyl pyrazoles <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong>,<br />

only <strong>in</strong> an ethylsulf<strong>in</strong>yl substituent replac<strong>in</strong>g the trifluromethylsulf<strong>in</strong>yl moiety. It is an <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong><br />

recommended for alfalfa, cotton, peanut, <strong>rice</strong> and soybean highly active on st<strong>in</strong>k bugs, planthoppers<br />

and aphids.it is an <strong>in</strong>hibitor to neural transmission by GABA. It has low toxicity to fish and birds but<br />

affects silkworms.<br />

NEONICOTINOIDS<br />

Imidacloprid: C H C1N 0 . Chemically it is 1 - (6 - chloro - 3 - pyridylmethyl) - N nitroimidazolid<strong>in</strong>-2 -<br />

9 IO 5 2<br />

ylideneam<strong>in</strong>e. It is a systemic <strong><strong>in</strong>secticide</strong> with stomach and contact action. Controls suck<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sects,<br />

soil <strong>in</strong>sects, <strong>rice</strong> water weevil etc. Used as a seed dress<strong>in</strong>g or foliar/soil treatment for control <strong>of</strong><br />

pests <strong>of</strong> cotton, <strong>rice</strong>, etc. Acute oral LD for rat is 450 mg/kg; dermal for rat is > 5000 mg/kg.<br />

50<br />

Thiamethoxam: C H ClN O S (EZ)-3-(2-chloro-1, 3-thiazol-5-ylmethyl)-5- methyl-1, 3,5-oxadiaz<strong>in</strong>an-4-<br />

3 10 5 3<br />