Ploughshares Monitor - Project Ploughshares

Ploughshares Monitor - Project Ploughshares

Ploughshares Monitor - Project Ploughshares

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

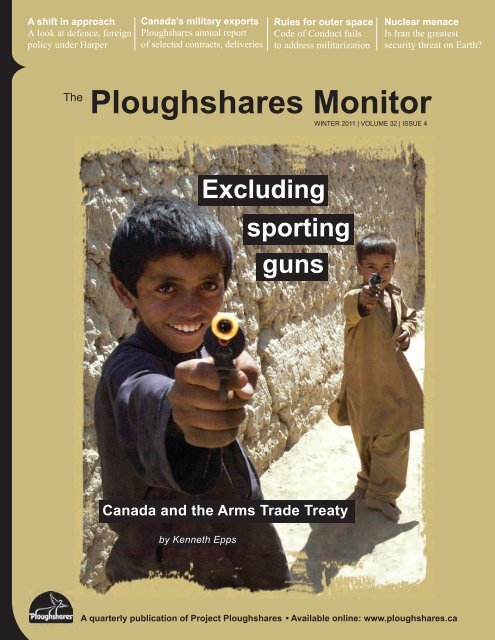

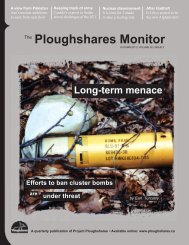

A shift in approachA look at defence, foreignpolicy under HarperCanada’s military exports<strong>Ploughshares</strong> annual reportof selected contracts, deliveriesRules for outer spaceCode of Conduct failsto address militarizationNuclear menaceIs Iran the greatestsecurity threat on Earth?The<strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>WINTER 2011 | VOLUME 32 | ISSUE 4ExcludingsportinggunsCanada and the Arms Trade Treatyby Kenneth EppsThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Sum- 1A quarterly publication of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> • Available online: www.ploughshares.ca

ContentsWinter 201138Civilian or military firearms? Cover storyCanada’s contradictory position on the Arms Trade Treaty.by Kenneth EppsCanada’s largest military contractorsMilitary contracting from sea to sea.by Kenneth EppsThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>Volume 32 | Issue 4PROJECT PLOUGHSHARES STAFFJohn Siebert Executive DirectorKenneth EppsMaribel GonzalesDebbie HughesTasneem JamalCesar JaramilloAnne Marie KraemerMatthew PupicWendy StockerThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is the quarterlyjournal of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, the peacecentre of The Canadian Council of Churches.<strong>Ploughshares</strong> works with churches,nongovernmental organizationsand governments, in Canada and abroad,to advance policies and actions that preventwar and armed violence and build peace.<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> is affiliated withthe Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies,Conrad Grebel University College, Universityof Waterloo.101214162023Canadian military exportsSelected contracts or deliveries reported in 2010.Warrior, neighbour, partnerExaming Canada’s shift in foreign policy under Harper.by John SiebertThe nuclear menaceSabre-rattling over Iran misses the root of the problem.by Cesar JaramilloLimited rules of engagementProposed outer space code of conduct falls short.by Cesar JaramilloA lukewarm responseLittle enthusiasm for a new international security paradigm.by John SiebertBooks etc.Samantha Nutt, Andrea Charron, Small Arms Survey 2011,Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011.Office address:<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>57 Erb Street WestWaterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 Canada519-888-6541, fax: 519-888-0018plough@ploughshares.ca; www.ploughshares.ca<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> gratefully acknowledgesthe ongoing financial support of the manyindividuals, national churches and churchagencies, local congregations, religious ordersand organizations across Canada that ensurethat the work of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>continues.We are particularly gratefulto The Simons Foundationin Vancouverfor its generous support.And we gratefully acknowledge the specialfinancial contribution of Mersynergy CharitableFoundation in 2011.All donors of $50 or more receivea complimentary subscriptionto The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>. Annualsubscription rates for libraries and institutionsare: $30 in Canada; $30 (U.S.) in the UnitedStates; $35 (U.S.) internationally. Single copiesare $5 plus shipping.Unless indicated otherwise, material may bereproduced freely, provided the author andsource are indicated and one copy is sentto <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>. Return postageis guaranteed.Publications Mail Registration No. 40065122.ISSN 1499-321X.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is indexedin the Canadian Periodical Index.Photos of staff by Karl Griffiths-FultonPrinted at Waterloo Printing, Waterloo, Ontario.Printed with vegetable inks on paperwith recycled content.COVER: Boys playing with toy guns run into a village alley in Bagram, Afghanistan.Eric Kanalstein/UNWe acknowledgethe financial supportof the Government of Canadathrough the Canada Periodical Fundof the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Civilian or military firearms?The Canadian Criminal Code makes no distinction,but Canada has proposed one for the ATTBy Kenneth EppsAt the July 2011 ArmsTrade Treaty (ATT)Preparatory Committeemeeting in New York, theCanadian delegationcaused a stir when it called for additionallanguage in the chair’s draft paper to recognizethat “there is a legal trade in smallarms for civilian uses, including for sporting,hunting and collecting purposes”(Canada 2011). The Canadian statementcontinued, “with regard to the inclusionof small arms and light weapons, Canadasupports the proposal made by Japan andItaly in March to exclude sporting andhunting firearms for recreational use fromthe treaty.”This was the first occasion whenABOVE: Guns areprevalent among theKaramoja in Uganda.Kristopher Carlson/IRINThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 3

ARMS TRADE TREATYCanada’s existing export controls neither define shooting and huntingfirearms, nor do they exclude transfers of these firearms from thecontrol process.Kenneth Eppsis SeniorProgramOfficerwith <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong>.kepps@ploughshares.caCanada called for weapons exemptionswithin the scope of the treaty. It marked asignificant change from earlier statementsin which Canada supported the inclusionof all small arms and light weapons(SALW) in the treaty scope without exceptions.1Many states raised objections toCanada’s statement. Mexico quickly respondedby noting that “different interpretationsfor military and recreational useof firearms open gaps for subjective interpretation”of the treaty. Mexico was worriedthat the proposed Canadianexemptions would create transfer loopholesfor many of the weapons that arecontributing to the current criminal carnagein that state.Mexico’s concerns are justified. Thereare no internationally accepted definitionsto differentiate civilian from militaryfirearms, nor is there agreement on whatdefines shooting and hunting firearms andtheir recreational use. Different nationalinterpretations of what constitutes a huntingrifle, for example, could facilitatebreaches of UN arms embargoes and leadto other illicit or irresponsible weaponstransfers.International and national lawMultilateral agreements to reduce and preventillicit transfers of firearms and smallarms contain inclusive definitions inrecognition of the inherent danger posedby all illicit arms. For example, the UNFirearms Protocol 2 defines a firearm as:any portable barrelled weapon that expels,is designed to expel or may bereadily converted to expel a shot, bulletor projectile by the action of an explosive.Other multilateral treaties use evenbroader definitions. 3 Many national lawsdefine firearms similarly. Canada’s CriminalCode, for example, states that afirearm is:a barrelled weapon from which anyshot, bullet or other projectile can bedischarged and that is capable of causingserious bodily injury or death to aperson, and includes any frame or receiverof such a barrelled weapon andanything that can be adapted for use asa firearm.The Canadian Criminal Code classifiesfirearms as automatic, imitation, prohibited,restricted, or replica, and defines ahandgun as “a firearm that is designed, alteredor intended to be aimed and fired bythe action of one hand.” Automaticfirearms designed for military use andmany handguns are prohibited, whilemany hunting rifles and shotguns used bycivilians are non-restricted, that is, they falloutside the definitions of the Criminal4The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

ARMS TRADE TREATYCode. Some handguns that may be used ininternational sporting competitions are restricted,not prohibited.Criminal Code classifications are basedon physical characteristics of firearms,such as barrel length, cartridge calibre, oroperating aspects. Definitions and classificationsof firearms in Canadian law, as ininternational conventions, do not referencethe use of firearms or their users,whether civilian, police, or military.This is also the case for the multilateralinstruments combatting illicit SALW.Since the end of the Cold Warthe SALW class of weaponshas been recognized as amajor global threat to humansecurity. States have agreed toseveral regional and global instrumentsto combat the proliferationand misuse ofSALW, most notably the 2001UN Programme of Action onsmall arms and light weapons.A 1997 UN panel of governmentalexperts has loosely defined“small arms” as thoseweapons designed for personaluse and “light weapons”as those designed for use byseveral persons serving as acrew.Although the SALW of“main concern” in the panel’sreport were those “manufacturedto military specificationsfor use as lethal instrumentsof war,” the panel proposeddefinitions based on inclusivesubcategories. For small armsthese are: revolvers and selfloadingpistols, rifles and carbines,submachine guns,assault rifles, and light machineguns. The subcategoriesof light weapons are: heavymachine guns, hand-held under-barrel andmounted grenade launchers, portable antiaircraftguns, portable anti-tank guns andrecoilless rifles, portable launchers of antiaircraftmissile systems, and mortars of acalibre less than 100 mm (UNGA 1997,para 25). The small arms subcategories arethe weapons of greatest concern to manystates, especially those in the Global Souththat suffer from endemic armed violence.The Economic Community of WestAfrican States (ECOWAS) 2006 Conventionon Small Arms and Light Weapons,BELOW: A Toposaman in South Sudanstands with his beadedweapon.Kristopher Carlson/IRINThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 5

ARMS TRADE TREATYControlling Exports from CanadaThe Export Controls Bureau of theDepartment of Foreign Affairs providesinstructions for individuals and businessesintending to export “firearms.”In reports on exports of military goodsthe Bureau pointedly notes that exportsof sporting and recreational firearms arecontrolled and diversion risks investigated:Guy Oliver/IRINMost firearms exports from Canada are intended for sporting or other recreational use and not formilitary use. Since a large volume of Canadian firearms exports go to private end-users, steps aretaken to ensure items are not diverted into the illegal arms trade or used to fuel local violence.As part of this process, the bona fides of the end-users are thoroughly investigated. Canadian diplomaticmissions and other sources may provide information about destination countries’ firearmscontrol laws, procedures and enforcement practices.Their Ammunition and Other Related Materialsincludes firearms in the category ofsmall arms. The Convention uses the fivesmall arms subcategories of the UNpanel, but in its first Article adds a sixth,defined as “firearms and other destructivearms or devices such as an explodingbomb, an incendiary bomb or a gas bomb,a grenade, a rocket launcher, a missile, amissile system or landmine.” By combiningfirearms and small arms the ECOWASConvention is responding to West Africanexperience. In the wrong hands anyfirearm or small arm can be, and has been,destructive or deadly. The ECOWAS Convention,like the UN Programme of Action,does not distinguish between civilianand military small arms.Canada’s export controlsMeanwhile, Canada’s existing export controlsneither define shooting and huntingfirearms, nor do they exclude transfers ofthese firearms from the control process.Export Control List (ECL) Items 2-1 and2-2 within Group 2 military goods are definedas “smooth-bore weapons” and“other arms” less or greater than specifiedcalibres. Canadian export regulations andinstructions to exporters state clearly thatall firearms covered by Canada’s CriminalCode are included in these ECL categories.The small arms of the UN panelgenerally correspond to ECL Item 2-1goods. In contrast, ECL Item 2-2 goodsinclude light weapons, but also firearms oflarger calibre. Moreover, unlike most other6The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

ARMS TRADE TREATYECL goods, Item 2-1 and 2-2 weapons arenot defined as “specially designed for militaryuse” (DFAIT 2011, Table 3, p. 14).All relevant firearms are included, regardlessof their design.The Export Controls Bureau of theDepartment of Foreign Affairs providesinstructions for individuals and businessesintending to export “firearms.” In reportson exports of military goods the Bureaupointedly notes that exports of sportingand recreational firearms are controlledand diversion risks investigated:Most firearms exports from Canada areintended for sporting or other recreationaluse and not for military use.Since a large volume of Canadianfirearms exports go to private endusers,steps are taken to ensure itemsare not diverted into the illegal armstrade or used to fuel local violence. Aspart of this process, the bona fides ofthe end-users are thoroughly investigated.Canadian diplomatic missionsand other sources may provide informationabout destination countries’firearms control laws, procedures andenforcement practices. (DFAIT 2011,p. 3)Indeed, Canada’s proposal could condemnATT negotiations to lengthy exchangesabout firearms categories andconsume precious time required for moresubstantive issues. The four-week periodfor treaty negotiations in July 2012 will attendto all aspects of a major global convention.A great deal of work must bedone quickly to create a robust and meaningfultreaty. Those states that want aweak ATT—or no treaty at all—will seeksuch opportunities as that presented bythe Canadian proposal to block or disruptnegotiations. If Canada is to remainaligned with the majority of states thatsupport a strong Arms Trade Treaty, itmust withdraw its proposed weapons exclusions.Notes1. For example, “Canada continues to support efforts towards the negotiation of acomprehensive, legally binding Arms Trade Treaty that would regulate the trade inconventional arms, including small arms and light weapons.” Statement by AmbassadorMarius Grinius to the UN First Committee, October 8, 2009.2. Protocol against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Their Partsand Components and Ammunition, supplementing the United Nations Convention againstTransnational Organized Crime, entered into force 2005.Proposal could block negotiationsThe proposal by Canada to exclude sportingand hunting firearms for recreationaluse from the scope of an Arms TradeTreaty flies in the face of Canada’s commitmentsto international treaties andagreements. It even contradicts existingCanadian laws and regulations, especiallythe Export and Imports Permit Act,which governs all firearms transfers fromand to Canada. Canada is calling forweapons category exemptions that are notrecognized by international or Canadianlaw and, as a result, stand little to nochance of being adopted.3. In the 1997 Inter-American Convention against the Illicit Manufacturing of andTrafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and Other Related Materials, commonlyknown by the Spanish acronym CIFTA, firearms include the barreled weapons of theCriminal Code definition and also “any other weapon or destructive device such as anyexplosive, incendiary or gas bomb, grenade, rocket, rocket launcher, missile,missile system, or mine.”ReferencesCanada 2011. Statement by the delegation of Canada, Arms Trade Treaty Prepcom,July 14, 2011.Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada (DFAIT). 2011. Report on Export ofMilitary Goods from Canada 2007-2009.United Nations General Assembly. 1997. Report of the Panel of GovernmentalExperts on Small Arms. A/52/298.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 20117

Canada’s largest military contractorsKenneth EppsMilitary contracting is a multi-billion-dollar industrythat extends from coast to coast in Canada, data showsThe 20 largest military primecontractors in Canada wonover $3.3-billion in ordersduring the 2010-11 fiscal year, accordingto official sources. 1 Mostprime contracts—over $2-billion invalue—were awarded by the Departmentof National Defence (DND)(see the accompanying table). The remaining$1.3-billion in orders wereawarded by the Canadian CommercialCorporation, a Crown corporationthat arranges back-to-backcontracts between Canadian-basedsuppliers and foreign military customers,predominantly the Pentagon.General Dynamics Land SystemsCanada was again the outstandingprime contractor in 2010-11, winning$764-million in orders. Most wereplaced by the Pentagon for Strykercombat vehicles and mine-resistanttransport vehicles for U.S. troops inAfghanistan and Iraq. GDLS Canadahas been a dominant military primecontractor in Canada for over twodecades, delivering thousands of armouredvehicles to the U.S., Canada,Australia, New Zealand, and SaudiArabia.Other contractors represent therange of equipment and servicesprovided by the Canadian military industry.Irving Shipbuilding (No. 2)and Victoria Shipyards (No. 3) wonCanadian navy contracts related tothe refit of Halifax class frigates.Canadian Submarine ManagementGroup (No. 8) also won navy ordersfor Victoria class submarine support.General Dynamics OTS Canada (No.4) was awarded contracts for ammunitionand explosives from the Canadianand U.S. armies. Othercompanies received contracts to providemilitary electronics (Ultra Electronics),armour (Armatec), andlogistics services (SNC Lavalin PAE).The majority of Canada’s largestmilitary prime contractors are aerospacecompanies. These include HarrisCanada (No. 5), which won DNDorders to provide weapon systemsavionics to upgrade CF-18 fighter aircraft.Top Aces (No. 6) contractedfor pilot training with the Canadianair force. Canadian Helicopters wasawarded U.S. contracts for militaryhelicopter services in Afghanistanand elsewhere. In the sole exampleduring the year of a substantial primecontract from outside DND and thePentagon, Viking Air won a $69-millionorder to supply 12 Twin Otteraircraft to the Peruvian armed forces.It is important to note that theranking of Canadian military primecontractors does not include allmajor military contractors in Canada.Many companies with significant militarysales are omitted from the tablebecause most of their orders occuras subcontracts. Prime contractorsalso may be awarded subcontracts byother companies. However, especiallyin cases in which Canadian subsidiariessupply foreign parent corporations,subcontracts generally arenot reported. The subcontract datathat is made public is insufficient forcomparative purposes.Although this ranking of primecontractors cannot provide a comprehensivepicture of Canadian militarysales, it offers important insightinto Canada’s military corporations aswell as the nature, volume, and locationof military production. Militarycontracting is a multi-billion-dollarindustry that extends from coast tocoast in Canada. Most large contractorsare located in Quebec and Ontario,although the latest rankingsuggests that the greater Torontoarea is not the military powerhouse itonce was. Significantly, the latest contractfigures cover a time of peakglobal military expenditures. Futurecontract tables will demonstrate howmuch the imminent decline in militaryspending will affect Canadiancontractors. 8The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

CANADIAN MILITARY PRODUCTIONLargest Canadian Military Prime Contractors 2010-2011Rank CompanyMain Office or PlantCCCcontracts*DNDcontracts**Total1 General Dynamics Land Systems Canada London, ON $731,847,554 $32,025,584 $763,873,1382 Irving Shipbuilding Inc. Halifax, NS $469,569,057 $469,569,0573 Victoria Shipyards Company Ltd. Victoria, BC $279,248,981 $279,248,9814 General Dynamics OTS Canada Le Gardeur, PQ $112,766,894 $137,311,873 $250,078,7675 Harris Canada Inc. Calgary, AB $208,127,777 $208,127,7776 Top Aces Inc. Pointe Claire, PQ $199,679,683 $199,679,6837 Cascade Aerospace Inc. Abbotsford, BC $160,776,527 $160,776,5278 Canadian Submarine Management Group Ottawa, ON $151,381,278 $151,381,2789 Rheinmetall Canada Inc. St Jean sur Richelieu, PQ $136,779,971 $136,779,97110 Canadian Helicopters Ltd. Edmonton, AB $114,655,372 $114,655,37211 Lockheed Martin Canada Inc. Kanata, ON $286,983 $86,679,788 $86,966,77112 Ultra Electronics Tactical Communications Montreal, PQ $69,148,122 $336,425 $69,484,54713 Viking Air Ltd. Sidney, BC $69,325,289 $69,325,28914 Fleetway Inc. Halifax, NS $62,128,736 $62,128,73615 Orenda Aerospace Mississauga, ON $51,600,193 $10,450,000 $62,050,19316 Armatec Survivability Corp. Dorchester, ON $59,971,783 $869,392 $60,841,17517 AirBoss Engineered Products Inc. Acton Vale, PQ $49,328,380 $8,101,276 $57,429,65618 Aveos Fleet Performance Inc. St Laurent, PQ $50,946,433 $50,946,43319 SNC Lavalin PAE Inc. Ottawa, ON $50,000,000 $50,000,00020 SNC Lavalin Defence Programs Inc. Ottawa, ON $44,421,278 $44,421,278TOTALS $1,258,930,570 $2,088,834,059 $3,347,764,629*Prime contracts awarded by foreign military agencies (mainly U.S.) via the Canadian Commerical Corporation**Prime contracts awarded by the Canadian Department of National DefenceSources: Public Works and Government Services Canada, Canadian Commercial CorporationNote1. The value of DND contracts was obtained from Public Works and Government Services Canada “Contracts History” database. The value of CCCcontracts was obtained from an Access to Information request.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 9

Canadian military exportsSelected contracts or deliveries reported in 2010U.S. contractsSupplier Location Military product or serviceAvcorpAerostructuresCMC ElectronicsInc.Crown AssetsDisposalGeneralDynamicsCanadaContractvalueRichmond, BC F-35 Carrier Variant aircraft outboard wings** Not reported U.S. NavyMontreal, QC UH-60M & S-70i helicopter avionics** $24.8-million U.S. ArmyRecipientOttawa, ON 6 CF-5 fighter aircraft, engines & spare parts $6-million private security companyNepean, ON 1,000+ mine protected vehicle display units** Not reported U.S. Army277 RG-31 mine protected vehicles $300.2-millionGeneralDynamics LandSystems CanadaCorp.London, ONUpgrade kits & parts for mine protected vehicles $415.2-million24 light armoured vehicles & upgrade work $39.5-millionParts & repairs for Stryker combat vehicles**$381.7-millionDouble-V hulls for Stryker combat vehicles**$59.6-millionU.S. NavyU.S. ArmyHéroux Inc. Longueuil, QC B-1B bomber & other aircraft landing gear $16-million U.S. Air ForceHoneywell ASCAInc.Mississauga, ON F-22 & C-130J aircraft temp control sensors** $14.7-million U.S. Air ForceL-3 MAPPS Montreal, QC Fast Combat Support Ships machinery control** Not reported U.S. NavyL-3 Wescam Burlington, ON Imaging turrets for targeting & training systems $313.2-million U.S. Air ForceNorthstarAerospaceMilton, ON Apache helicopter transmission spares** $54.1-million U.S. ArmyUltra Electronics Montreal, QC Radio communication system $31.6-million U.S. Army* Estimated contract value** Subcontract with corporate prime contractorSource: Canadian Military Industry Database, <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>10The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

CANADIAN MILITARY EXPORTSNon-U.S. contractsSupplier Location Military product or serviceContractvalueRecipientArmatecSurvivabilityBell HelicopterTextronCanadaBombardierInc.CAE Inc.London, ONSurvivability kits for armoured vehicles $271.7-million AustraliaArmoured vehicle composite armour ** Not reported SwitzerlandMirabel, QC 2 Bell 412EP helicopters for counterinsurgency efforts** $24.8-million PakistanSouthport, MB Aviation & technical training for Air Force $2-billion Saudi ArabiaTornado aircraft simulators upgrade & training $58-million GermanyMontreal, QC Upgrade C-130H aircraft simulator Not reported “North Africa”Combat & trainer aircraft flight simulators** Not reported TurkeyCMCElectronicsInc.Colt CanadaCorp.Governmentof CanadaMontreal, QCHawk advanced jet trainers service support** Not reported FinlandT6-C trainer aircraft avionics** Not reported MoroccoPC-21 training aircraft flight management** Not reported UAEKitchener, ON 5,000 C8 carbine automatic firearms $20-million DenmarkOttawa, ON 6 armoured personnel carriers for UN mission $10-million* UgandaL-3 MAPPS Montreal, QC FFx frigate engineering control system Not reported South KoreaL-3 Wescam Burlington, ON 36 AH-6 attack helicopter targeting systems** $18-million* Saudi ArabiaMacDonaldDettwiler &AssociatesLtd.Richmond, BC Contract extension – unpiloted aerial vehicles surveillance in Afghanistan Not reported AustraliaMectronixSystems Inc.Montreal, QC CL-415 aircraft flight simulator Not reported SpainNorthstarAerospaceMilton, ON Lynx helicopter rotor heads** $7-million U.K.OSIGeospatial Inc.Ottawa, ON Nuclear attack submarine navigation software Not reported U.K.AW109 maritime helicopter engines** $4-million* BangladeshPratt &WhitneyCanadaThordon Ltd.UltraElectronicsLongueuil, QCBurlington, ONKing Air 350 air ambulance engines** $12-million* ColombiaC-295 transport aircraft engines** $2-million* FinlandSuper Tucano light attack aircraft engines** $8-million* IndonesiaAW139 helicopter engines** $4-million* LibyaC-295 transport aircraft engines** $10-million* IraqAW139 utility helicopter engines ** $12-million* PanamaOffshore patrol vessel propeller shaft bearings Not reported IndiaSigma Frigate propeller shaft bearings Not reported MoroccoMilgem corvette propeller shaft bearings Not reported TurkeyDartmouth, NS M-class frigate sonar systems $25-million NetherlandsViking Air Ltd.Sidney, BCDHC-6-200 Twin Otter aircraft repairs Not reported Argentina6 Twin Otter 400 aircraft for amphibious use $30-million* VietnamThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 11

Warrior, neighbour, partnerA look at Canada’s shift in foreign policy under HarperBy John SiebertIn October, <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Executive Director John Siebert gave a speech on Canadian defence and foreign policy as part of aseries sponsored by the Mir Centre for Peace at Selkirk College in Nelson, B.C. The following are excerpts from that speech.In the afterglow of the May 2, 2011 federal Canadian election, in which the Conservatives secured a majority government,Prime Minister Stephen Harper addressed the Conservative Party national convention on June 10 toextol the virtues of his foreign policy. Canada now would be known according to three alliterating foreign policyarchetypes: the courageous warrior, the compassionate neighbour, and the confident partner. He declared that, in internationalrelations, “strength is not an option; it is a vital necessity. Moral ambiguity, moral equivalence…are not options,they are dangerous illusions.”Shilo Adamson/DNDI’m not dismissing peacekeeping, and I’m not dismissing foreign aid—they’re all importantthings that we need to do, and in some cases do better—but the real defining moments forthe country and for the world are those big conflicts where everything’s at stake and whereyou take a side and show you can contribute to the right side.Stephen Harper, July 2011 (Whyte 2011)12The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

For the Gaddafis of this world pay no attention to the force of argument.The only thing they get is the argument of force.Stephen Harper, September 2011, congratulating Canadian Forcesin Italy for their role in the NATO-led Libya campaign.Right now, the brutal reality is it doesn’t matter to these countries whatposition Canada takes on these issues because our current governmenthas left the country so weak.Stephen Harper, 2006 federal election campaign.Roxanne Clowe/DNDThe prosecution of war entails the deliberate, planned, and executed taking of life, often on a massive scale; anddestruction of property, often making vast landscapes uninhabitable or unusable for years or decades. Whether weparticipated in, or were even alive during the great conflagrations of the 20th century, we know the destructive powerof mechanized war; as well as the slow, grinding, debilitating destruction of insurgencies in emerging and post-colonialstates in underdeveloped regions of the world. The estimated number of total deaths is staggering—in excess of160 million.Putting a strong defence at the centre of Canadian foreign policy in peacetime is a remarkable first. It also is consistentwith the codification of Conservative policy in the 2008 Canada First Defence Strategy. More shopping list thanpolicy document, it shows the defence budget expanding “from approximately $18-billion in 2008-09, to over$30-billion by 2027-28.”<strong>Project</strong>ing leadership abroad can take many forms…. One thing is clear, however: Canada cannot lead withwords alone. Above all else, leadership requires the ability to deploy military assets, including ‘boots on theground.’ (DND 2008, p. 9)Most Canadians would be surprised at this change in how Canada presents itself officially to the world. Harper hasput a strong military at the heart of Canadian foreign policy, not just defence policy. And he has gone a step further,calling alternative approaches “timid and trendy.”To this I ask: Does this approach to Canada’s role in the world make sense in its own terms? Is this approach necessary,inevitable, logical, and in the best interests of Canada and Canada’s neighbours, both near and far?My short answer to each of these questions is, No. ReferencesDepartment of National Defence (Canada). 2008. Canada First Defence Strategy.Whyte, Kenneth. 2011. In conversation: Stephen Harper. Maclean’s, July 5.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 13

The nuclear menaceCesar JaramilloThe West’s focus on Iran distracts from the real threat—the stubborn refusal to give up nuclear weaponsThe Director-General of the International Atomic Energy Agency addresses the 2010 Review Conference of the Partiesto the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in New York on May 3, 2010. Eskinder Debebe/UNThe latest report from the InternationalAtomic EnergyAgency (IAEA) on Iran’snuclear program has increased the alreadyinflammatory rhetoric againstthe Islamic Republic. The West iscalling for tougher sanctions whilereiterating that all options—includingmilitary force—are on the table.Certainly, Iran’s lack of transparencyregarding its nuclear programcreates legitimate internationalsecurity concerns. But western policymakersseem to overlook the simplefact that the current standoff is inpart the result of an unsustainablenuclear weapons regime that perpetuatesa double standard between statesthat have nuclear weapons and thosethat do not.As the Canadian government announceda new set of sanctionsagainst Iran on November 21, ForeignAffairs Minister John Baird(DFAIT 2011) said that “the regimein Tehran poses the most significantthreat to global peace and securitytoday.” Not so. In reality, the gravestthreat to international security lies inthe very existence of nuclearweapons and the stubborn reluctanceby their possessors to give them up.A blatant disregard for a 40-year14The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

NUCLEAR DISARMAMENTcommitment to disarm under theNuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty(NPT) creates strong proliferationpressures that can only be counteractedby the complete elimination ofnuclear weapons. What is needed is aglobal legal ban on the possession,deployment, and use of these instrumentsof mass destruction. No exceptions,no exemptions.A central conclusion reached bythe authoritative International Commissionon Nuclear Non-proliferationand Disarmament (2009, p. xvii),co-chaired by former Australian ForeignAffairs Minister Gareth Evans,is that “so long as any state has nuclearweapons, others will wantthem.” This underscores the untenablenature of an inherently unjustinternational security architecture, inwhich the countries that possess nuclearweapons are also the arbiterswho decide that others cannot havethem.As pundits and policymakers graduallyincrease the incendiary natureof their fear mongering, some importantfacts get lost. Half-truths, fallaciousreasoning, and hastyspeculations not only perpetuate preconceivednotions about Iran’s nuclearambitions, but also divertattention from the more urgent problemof nuclear weapons possession.So let us be clear: while Iran hasunquestionably been less than forthcomingabout its nuclear program,there is no evidence to suggest thatthe country has a nuclear weapon.The argument that through its nuclearenergy program Iran is inchingcloser to a weapons capability is certainlytrue. But it is also true that anycountry with a civilian nuclear programis on a path that could possiblylead to the development of nuclearweapons.As nuclear disarmament expertsRamesh Thakur, Jane Boulden, andThomas G. Weiss (2008, p. 15) haveput it, “nuclear energy for peacefulpurposes can be pursued legitimatelyto the point of being perhaps ascrewdriver turn away from aweapons capability.” From this perspective,the need for strict IAEA inspectionsof Iranian nuclear facilitiesis undeniable, and any resistance bythe Iranian government to such internationaloversight is reprehensible.Yet it is hard to ignore the starkcontrast between the rigorous attentiongiven to Iran’s nuclear energyprogram, which could, potentially,one day result in a nuclear weapon,and the remarkable lack of scrutinyof Israel’s advanced nuclear weaponsprogram. Israel is the only country inthe volatile Mideast actually in possessionof nuclear weapons, and isnot a member of the nearly universalnon-proliferation treaty, thus keepingit immune from the sort of non-proliferationand disarmament obligationsexpected of other countries.But the West seems content to acceptIsrael’s policy of deliberate ambiguityabout its nuclear arsenal withfew reservations. Such issues are ripefor discussion at a conference to beheld in 2012 on a Middle East free ofweapons of mass destruction.Domestic political considerationsin Iran must be thoughtfully acknowledged.One need not walk amile in President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’sshoes to realize that hiscountry is flanked by thousands ofAmerican troops, and is within reachof Israeli nuclear weapons. By aggressivelyclaiming its right to a nuclearenergy program—as allowed bythe NPT—and by portraying theWest as hostile and unfair, Iran’s governmentearns the support of a domesticconstituency.Ominous warnings about Iran’sthreshold nuclear-weapons capabilityhave been made since the early1990s. Some have come with precisetimelines that indicated that Iran wasX years away from a nuclear weapon.But so far, there is no smoking gun.Nuclear technology has importantimplications for international peaceand security. Thus, it is crucial thatIran respond to unanswered questionsabout the peaceful nature of its nuclearprogram and fully embrace strictinternational oversight of its nuclearfacilities. But the most urgent concernabout nuclear weapons is broader thanIran. The root of nuclear insecurity isin the continued possession of nucleararsenals by a few states, despiteoverwhelming evidence that suchweapons lack any political, military, ormoral justification. This article first appeared in theWaterloo Region Record on Nov. 24.ReferencesForeign Affairs and International TradeCanada (DFAIT). 2011. Modification—Minister Baird expands sanctions on Iran.News release, November 21.International Commission on NuclearNon-proliferation and Disarmament. 2009.Eliminating Nuclear Threats: A PracticalAgenda for Global Policymakers.Thakur, Ramesh, Jane Boulden &Thomas G. Weiss. 2008. Can the NPTRegime be fixed or should it be abandoned?Dialogue on Globalization No. 40.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 15

Limited rules of engagementEven if the Code of Conduct for Outer SpaceActivities is adopted, a significant void will remainABOVE: The space agebegan with the launch ofSputnik 1 in 1959. Visitorsto the UN in NewYork admire a model ofthe satellite in 1962.United Nations Photo16The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

SPACE SECURITYThe draft Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities proposed by the European Union is currently undergoinginternational consultations and is expected to be open for signatures in 2012. If adopted, the Code will establisha set of voluntary confidence-building measures aimed at increasing transparency and responsible behaviour inouter space activities. However, the Code of Conduct fails to tackle urgent questions relating to the militarizationand weaponization of outer space.By Cesar JaramilloSpace security dynamics havechanged dramatically sincethe dawn on the space ageover half a century ago whenSputnik 1 became the first artificialsatellite launched into Earth’s orbit.For years after, the United States and SovietUnion were the only two players inthe race for space supremacy, permeatedby Cold War rivalry.The end of the Cold War, the emergenceof a highly profitable space servicesindustry, and a sharp decrease in the financialand technological barriers to entryhave all contributed to a dramatic increasein the number of actors with space assets.At least nine states have acquired an autonomousorbital launch capability, andover 60 nations or consortia now have assetsin space that have been launched eitherindependently or in collaborationwith others (Jaramillo 2011, p. 17). Thisnumber will continue to grow every year.The commercial sector is also growingsteadily, with revenues in the hundreds ofbillions of dollars. Space-based commercialapplications such as GPS and satelliteTV and radio are more and more common.And while it is desirable to expandthe pool of stakeholders with a vested interestin the sustainable use of space, thelimited nature of some space resourcesposes increasingly complex governancechallenges to ensure equitable access fornewcomers.There is also growing tension betweena conception of space as a peaceful globalcommons and one that views space primarilyas a strategic military domain. Theuse of space assets for military applicationssuch as reconnaissance, intelligence,and surveillance has long been commonplacefor countries like the United Statesand Russia. Now more countries are attachinggreater importance to the benefitsand strategic advantages of space-basedmilitary applications.Not surprisingly, contemporary U.S.space policy documents, such as the 2010National Space Security Strategy, characterizethe space domain as congested, contested,and competitive. Yet, after more than50 years, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty remainsthe primary point of reference forinternational space law, despite growingevidence that its precepts and underlyingassumptions no longer reflect the drasticallychanged reality of outer space activities.In this context, the need for anadequate policy instrument for outerspace activities that effectively tackles themost salient challenges currently facingthe space domain becomes ever more apparent.Of the policy instruments thathave been put forward by different actors,1 the one that seems most likely toThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 17

SPACE SECURITYBELOW: The SpaceSecurity Index, managedby <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>,and the PermanentMission of Canadato the UN give a specialpresentation at the UNin New York in October.Rick Bajornas/UNgalvanize broad international support isthe EU’s proposed Code of Conduct forOuter Space Activities.Code LimitationsThe many challenges facing the outerspace domain can be grouped into twobroad categories. On the one hand, thereare those related to the risks to space assetsthat result from ‘normal’ peacefulspace operations. These include, for instance,the risk of collision between twosatellites or between a satellite or mannedspacecraft and a piece of space debris. Onthe other hand, there are risks associatedwith the militarization and potentialweaponization of space, which are collectivelyreferred to in the United Nationssystem as PAROS—the Prevention of anArms Race in Outer Space.The provisions of the Code of Conductaim to address the first, through nonbindingcollaborative mechanisms such assharing data related to positions, manoeuvres,and activities of space assets. Concernsrelated to PAROS, which are at leastas urgent as those related to collisionavoidance, are left essentially unresolved.Even though the Code, for example, callsupon states to respect “the security, safetyand integrity of space objects in orbit consistentwith international law” (my emphasis)—whichcould be interpreted as ameasure to protect space assets againstacts of aggression—the reality is that internationallaw in this area is significantlylacking. This governance void is highlytroubling, as a weaponized space domaincould be a destabilizing factor for internationalpeace and security on Earth.Referring to multilateral, global diplomacy,one author argues that “debates inthis context tend to circle endlesslyaround relatively insignificant problems18The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

SPACE SECURITYwhile the true issues are left practically unaddressed”(Krause 2007). Certainly, thisassessment cannot be fully applied to thedebates about the scope and limitations ofthe Code, as the issues it tackles are anythingbut insignificant. However, the lackof attention and energy given by the internationalcommunity to the problems withspace weapons must be acknowledged, asmust the dire consequences for space andterrestrial security if such problems arenot addressed.In recent years, for example, countriessuch as the U.S. and China have conductedanti-satellite weapon (ASAT) tests,which have not only raised internationalconcerns about the inherently belligerentnature of these capabilities, but have createdhundreds of thousands of pieces ofnew space debris. Each piece poses anundiscriminating threat to the space assetsof all actors, including those that createdit in the first place. Yet no policyinstruments exist to prevent future ASATtests.The link between Ballistic Missile Defence(BMD) systems and ASAT capabilitiesis often overlooked in policydiscussions about space security. Indeed,“the same kinetic-kill interceptors that candestroy a missile in-flight could also be capableof destroying a satellite in low Earthorbit (and in doing so, effectively becomeanti-satellite weapons, or ASATs)” (Weeden2009). This relationship is problematicfrom a space security perspective, asthe similarity between the two technologiescould contribute to the weaponizationof outer space, while encouraging morecountries to deploy similar systems.The Code of Conduct does hold value.To be sure, its proponents have alwaysconceded that it was designed to deal with‘soft’ issues (i.e., not weapons). If it isadopted, the Code will do exactly what itopenly sets out to do: codify a set of nonbindingtransparency and confidencebuildingmeasures. It is the broader multilateralgovernance architecture that hasnot effectively responded to legitimateconcerns regarding the perils of spaceweaponization.Even if the Code is adopted in 2012, asignificant governance void will remain.No clear norms are in place to address thepossibility of an arms race in outer space.The risks associated with such a prospectmay not be apparent during peacetime,when nations exercise self-restraint in thedeployment and use of weapons againstspace assets. But self-restraint is no substitutefor effective governance mechanisms,codified in international law, especiallywhen tensions are running high.The matters addressed by the Code aresignificantly less contentious than thoserelated to space weaponization. Still, theEU has had to work hard to gain the internationalsupport needed to secureadoption of the Code. The reality that discussionson the weaponization of spacewill be more complex should encouragepolicymakers to start them sooner ratherthan later. It is high time for the internationalcommunity to give this issue the attentionit demands. Note1. For a brief overview of different space security policy proposals, see CesarJaramillo, New competition for a space security regime, The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>,Summer 2010.ReferencesCouncil of the European Union. 2010. Document 14455/10.Jaramillo, Cesar, ed. 2011. Space Security 2011.Krause, Joachim. 2007. Nuclear Proliferation and International Order. Paperpresented to the International Conference “Global Security in the 21st Century:Perspectives from China and Europe.”U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. National Security Space Strategy UnclassifiedSummary.Weeden, Brian. 2009. The space security implications of missile defense. The SpaceReview, September 28.Cesar Jaramillois a ProgramOfficerwith <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong>.cjaramillo@ploughshares.caThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011 19

A lukewarm responseJohn SiebertThe Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence proposesan alternative international security paradigmIn The Structure of Scientific Revolutions(1962), Thomas Kuhnproposed that dramatic changesperiodically take place in the scientificworld. Replicable experimentationresults in an accumulation ofanomalies not easily explained byprevailing theories. A new theoreticalexplanation—a paradigm shift—isput forward, offering a fuller or morecoherent explanation that accountsfor the anomalies and propels scienceforward. Among Kuhn’s exampleswas the shift from the Ptolemaic theoryof the earth as centre of thesolar system to the Copernican revolutionin cosmology.Before a new paradigm is adopted,however, established leaders and institutionsin the field fight against it.People whose careers and institutionsare built on the old paradigm ofknowledge naturally try to preservetheir places in the firmament of prestige(and funding). This institutionalinstinct of steadfastness in the faceof contrary evidence or a better explanationaffects science as much asreligion and politics. As Germanphysicist Max Planck, the founder ofquantum physics, quipped, “Scienceadvances one funeral at a time.”These liminal moments of unresteventually give way to general acceptanceof the new paradigm. Experimentationin line with the newparadigm results in new anomaliesand the cycle repeats. These cyclescan take years or decades or centuries.These thoughts went through mymind as I participated in the SecondMinisterial Review Conference of theGeneva Declaration on Armed Violenceand Development (October31– November 1). Twentysome yearsafter the end of the Cold War, astruggle is being waged for a new internationalsecurity paradigm. Thestatus quo is so-called realism, whichthreatens the use of force, backed byoverwhelming military expenditures,by military coalitions that are basedon national interest-defined security.The new players in the field are evidenced-basedapproaches that pointto poverty, social and economic inequality,and lack of political participationas primary sources ofindividual and community insecurity.Investment in development, alongwith reforming and redefining traditionalsecurity mechanisms such aspolice, military, and intelligence, representhope and the way forward.Amidst all the sound and fury ofthe military interventions in Iraq andAfghanistan, with the Great War onTerror providing policy (or more accuratelyrhetorical) cover, the worldfails to look squarely at the evolvingpicture of violence and conflict. Thenumber of armed conflicts, includingthose within countries, has decreaseddramatically over the past 15 years.This decrease is matched by the decreasein the number of direct casualtiesin those wars that stubbornlycontinue.This good news is clouded by thefindings of the updated report fromthe Geneva Declaration Secretariat,The Global Burden of Armed Violence(2011). Keith Krause from SmallArms Survey, who provided anoverview of the report at the conference,said that more than half a millionpeople die each year as a directconsequence of armed violence—about 1,500 each day. The vast majorityof these deaths take placeoutside war zones. It is estimated that1.5 billion live in circumstances ofendemic armed violence, primarily inthe low-income countries of theglobal south.Armed violence is concentrated in14 countries, which have violentdeath rates higher than 30 per100,000. Only six of these countriesare considered to be “at war.” Sevenof the 14 are in Latin America andthe Caribbean. Clearly, countries thatrate low on the human developmentindex are much more prone to highrates of homicide. No low-incomeand violence-affected country hasachieved a single Millennium DevelopmentGoal (MDG), and none islikely to do so by 2015, the targetdate to meet all MDGs.Surprisingly, no clear-cut relationshiphas been found between theprevalence of firearms and deaths by20 The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

ARMED VIOLENCE REDUCTIONOPPOSITE: Residentsof Kibera, Nairobi’slargest slum, hold a rally.The framers of theMDGs (Millennium DevelopmentGoals) deliberatelyavoided a goal toreduce violence, eventhough countries thatrate low on the humandevelopment index aremuch more prone tohigh rates of homicide.Joseph Mwelu/IRINarmed violence, but where there arehigher homicide rates, the percentageof homicides caused by firearms increases.Of the approximately526,000 victims who have died violentlyeach year since 2005, 66,000have been women. Young men between15 and 30 years of age are theprimary perpetrators and victims ofarmed violence. The inherent tragedyof the loss of life through armed violenceis compounded by the factthat endemic violence hinders development.Research clearly shows that armedviolence can be controlled and reducedthrough innovative programmingby governments and civilsociety that• makes the criminal justice sectormore effective• enhances dispute resolutionmechanisms• holds governments accountablefor reducing violence• works with municipalities inwhich rapid urbanization can concentrateviolence• ensures that the people affectedare part of the solution throughcommunity-based initiatives andgenuine cooperation with the securityservices.In a country such as Guatemala,with extreme levels of criminalarmed violence, remedial educationfor the young, livelihood training,banning firearms, restricting alcohol,and improving local infrastructuresuch as street lighting can reduce violentdeaths among those who are vulnerableto gangs and illegal pursuits.In effect, the social contract must beshored up with services and hope.Rubem César Fernandes from VivaRio in Brazil told the Geneva gatheringthat we know what the solutionsare. The challenge is to get the policeand military to work with each otherand with local people, along withlocal churches, municipalities, and developmentactors. Asked why LatinAmerica is so plagued by armed violence,he responded that “it is not ourdestiny.” Inequality, not poverty, is aspur to armed violence. In a certainsense, armed violence is a sign ofprogress in that people are not justgiving up. There is an organized ifcriminal effort to make somethinghappen in the face of exclusion fromthe benefits of a growing economy.What the Geneva Declaration isreally doing is proposing an alternativesecurity paradigm—and the lukewarmresponse from states is telling.At the turn of the century, the MillenniumDevelopment Goals processcreated seven evidence-based stan-The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 201121

ARMED VIOLENCE REDUCTIONdards to measure investment fromdonor countries and concrete implementationin the field by 2015. All ofthe MDGs are worthy, dealing withadvances in areas such as maternaland child health and access to primaryeducation.What the framers of the MDGsdeliberately avoided was a goal to reduceviolence, even though violencestops and reverses developmentprocesses. In part this was a functionaldecision to keep the spheres ofdevelopment and security separate.There is still suspicion in some developmentquarters about the securitizationof aid or the diversion ofdevelopment assistance funding toshore up weak police and militaryforces in low-income countries. Butrejection of such a goal was also astandard response by the proponentsof traditional hard security, who refuseto address the social and economicconditions that fosterviolence.The government of Switzerlandand the UN Development Programme(UNDP) began the GenevaDeclaration initiative in 2006 to addressthe glaring omission of armedviolence in the MDG process. Norwayalso has provided state leadershipand added funding to Swisscontributions to encourage researchon measureable indicators of armedviolence. Support for civil society organizationsto participate has beenprovided. Other international bodies,such as the Development AssistanceCommittee of the Organisation forEconomic Co-operation and Developmentand the World Bank, havedeveloped their own policy work onthe impact of violence on social andeconomic development.One hundred and twelve stateshave now signed on to the GenevaDeclaration, but state representationat the recent conference was generallynot at the Ministerial level.Speeches from states often playeddown the problems of armed violencein their countries. Enhancedglobal and regional research on violence-affectedareas was applauded,but more support is now required forcommunity-level mitigation of armedviolence.“What is the valueproposition of alargely Euro-Atlantic,NATO-focused confabof security-sectorleaders?”The old security paradigm is wellentrenched and is not about to easilycede its place to another. Justfollow the money. Annual worldwidemilitary expenditures, accordingto the Stockholm InternationalPeace Research Institute, are nowUS$1.5-trillion. The U.S. accountsfor almost half of that amount;NATO states, including Canada andthe U.S., are responsible for twothirdsof all military expenditures.The annual economic and socialdrain of armed violence is estimatedto cost more than $160-billion,more than all of the OfficialDevelopment Assistance contributedby donor countries.Cuts may be coming to NATOmilitary budgets, but not because ofa shift from military spending to developmentand community-level security.Rather, dire economic anddebt realities in the U.S. and Europecould force reductions.In recent commentary on the $2-million Canadian-funded weekend securityconference held in Halifax,Nova Scotia, Dr. Taylor Owen pointedlyasked, “What is the value propositionof a largely Euro-Atlantic,NATO-focused confab of securitysectorleaders?” He noted that, whileit is “a trope in international relationsto say that the world of securitychanged ‘after the end of the coldwar,’” it has indeed changed. “Thesecurity conversation now rightly involvesany number of auxiliaries tomilitary affairs, including development,human rights, the environment,public health, local violence,and so on.”Thomas Kuhn, had he been a securitypolicy expert rather than a historianof science, could not have saidit better. A paradigm shift is in theoffing, but the entrenched institutionalinterests of the traditional securityworld are valiantly sticking totheir guns. We are left to wonder: willwe see a shift to this new paradigmof security in the near future? jsiebert@ploughshares.caReferencesGeneva Declaration Secretariat. 2011.Global Burden of Armed Violence: LethalEncounters. New York: CambridgeUniversity Press.Owen, Taylor. 2011. Conferencing inHalifax while Rome burns? Blog, TaylorOwen.com, November 25.22 The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 2011

Books etc.Damned Nations: Greed,Guns, Armies, and AidSamantha NuttMcClelland & Stewart, 2011Hardcover, 240 pages, $29.99Small Arms Survey 2011:States of SecurityCambridge UniversityPress, 2011Paperback, 352 pages, $34.99The founder of War Child examines the economicincentives and Western inadequacies that fuel violence inthe developing world. Writes Nutt: “Canada, which isamong the world’s top 10 arms exporters, has had one ofthe lowest international arms transparency ratings.”Produced annually by a team of researchers basedin Geneva and a worldwide network of localresearchers, Small Arms Survey 2011 looks at,among other things, the use of private securitycompanies by multinational corporations.UN Sanctions and Conflict:Responding to Peaceand Security ThreatsAndrea CharronRoutledge, 2011Hardcover, 230 pages, $130Written by a Research Associate at Carleton University,this book examines the application of the UN SecurityCouncil’s mandatory sanctions since 1946 and,in particular, the regimes adopted for specific typesof conflict.Global Burden of ArmedViolence: Lethal EncountersCambridge UniversityPress, 2011Paperback, 175 pages, $34.99This illustrated volume presents country-level estimatesof violent deaths worldwide, new findings on lethalviolence against women, and analyses of the negativeimpact of lethal violence on social and economicdevelopment.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> | Winter 201123

<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>Celebrates 35 YearsPlease join us for an anniversary event featuringkeynote speaker Samantha Nutt, founderof War Child and author of Damned Nations: Greed,Guns, Armies, and Aid7 p.m.Monday, February 27, 2012Knox Presbyterian Church50 Erb Street West, Waterloo ONFor more information, please visit: www.ploughshares.ca