Winter 2010 - Project Ploughshares

Winter 2010 - Project Ploughshares

Winter 2010 - Project Ploughshares

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

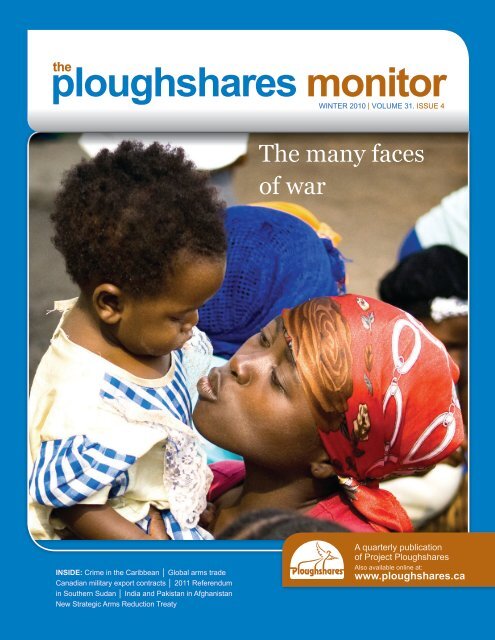

Contents3The many faces of war:As the nature of conflictchanges, traditionaldefinitions of warfarefall shortErnie Regehr7 Talking crime in theCaribbean with FrancisForbes: An interview912The limits to measuringthe global arms tradeKenneth EppsCanadian military exports:Selected contracts ordeliveries reported in 200913 India-Pakistan relations andthe impact on AfghanistanNicole Waintraub1618Brinksmanship, delay,and broken agreements:The Southern Sudanindependence referendumJohn SiebertFrom START to zero:The importance – andlimitations – of theNew Strategic ArmsReduction TreatyCesar Jaramillo23 Resources11Acronyms andabbreviationstheploughshares monitorStella plays with a child at the Heal Africa Transit Center in Goma,Democratic Republic of Congo. According to Gender-Based ViolenceExpert Mendy Marsh, a key component of reintegration after sexual violenceis “for the women to feel like they can move on and take care of theirchildren.” © Aubrey Graham/IRIN.STAFF: Kenneth Epps | Melanie Ferrier, intern | Maribel Gonzales | Debbie HughesTasneem Jamal | Cesar Jaramillo | Anne Marie Kraemer | Ernie Regehr | Nancy RegehrJohn Siebert, Executive Director | Wendy Stocker | Nicole Waintraub, intern | Christina WoolnerThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor is the quarterly journal of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, the peace centreof The Canadian Council of Churches. <strong>Ploughshares</strong> works with churches, nongovernmentalorganizations, and governments, in Canada and abroad, to advance policies and actions thatprevent war and armed violence and build peace. <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> is affiliated with theInstitute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Conrad Grebel University College, University of Waterloo.Office address: <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>57 Erb Street West, WaterlooOntario N2L 6C2 Canada519-888-6541, fax: 519-888-0018plough@ploughshares.ca www.ploughshares.ca<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> gratefully acknowledges the ongoing financial support of the manyindividuals, national churches and church agencies, local congregations, religious orders, andorganizations across Canada who ensure that the work of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> continues.We are particularly grateful to The Simons Foundation in Vancouverfor its generous support.All donors of $50 or more receive a complimentary subscription to The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor.Annual subscription rates for libraries and institutions are: $30 (Canada), US$30 (US), US$35(international). Single copies are $5.00 plus shipping.Unless indicated otherwise, material may be reproduced freely, provided the author and sourceare indicated and one copy is sent to <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>. Return postage is guaranteed.Publications Mail Registration No. 40065122.ISSN 1499-321X.PAP Registration No. 11099.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor is indexed in the Canadian Periodical Index.Design: Creative Services, University of Waterloo.Photos of <strong>Ploughshares</strong> staff by Karl Griffiths-Fulton.Printed at Waterloo Printing, Waterloo, Ontario.Printed with vegetable inks on paper with recycled content.We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada throughthe Canada Periodical Fund (CPF) for our publishing activities.

The many faces of warAs the nature of conflict changes, traditional definitionsof warfare fall shortErnie RegehrBetween July 30 and August 4 thisyear, fighters of the DemocraticForces for the Liberation of Rwandaand elements of the Mai Mai, a localmilitia, entered Luvungi and surroundingvillages in the DemocraticRepublic of Congo (DRC) and, inone extended weekend, raped 150to 200 women and children, includinga number of baby boys. Theythen looted the area and moved on(Kaufman <strong>2010</strong>).News of the assaults did notreach international media outletsuntil weeks later, and when the UNthen investigated, it established thatthe number of rapes in the reportedincidents was actually 242. However,investigators also learned of another267 rapes in the district that had notbeen previously reported (Globe andMail <strong>2010</strong>).The context was the ongoing civilwar in the DRC, but somehow theterm “war” doesn’t come close to capturingthe scale of horror of Luvungi.The rapes are beyond extreme by anymeasure, but as part of the chaos andfighting that have engulfed the DRCsince 1990, the Luvungi victims representbut the tiniest fraction of thewar’s human toll. Five million deathsin the DRC are directly attributableto the war. Hundreds of thousandshave been raped; untold millions areinternally displaced. According toUNICEF, there are more than fourmillion orphaned children in the DRC. 1Contemporary war is largely “unofficial”and often unacknowledged. It israrely declared; flags and bugles don’therald its approach. The march to waris replaced by the gradual (or sometimesrapid) disintegration of order inseverely troubled societies and theinexorable descent into political andcriminal public violence.Indeed, “public violence” maywell be the more apt, though stillemotionally inadequate, term formany of today’s armed conflicts.Public violence is invariably linkedto longstanding social and politicalgrievances that remain chronicallyunaddressed and are allowed to festerand undermine confidence in publicinstitutions and processes. In turn,widespread rejection of public institutionsis transformed into lawlessnessand armed violence when ignoredgrievances are joined by a readyaccess to small arms – the pre-eminenthardware of public violence.When a state finds itself in thatdeadly combination of circumstances– pervasive grievance, loss of confidencein government, and abundantsupplies of user-friendly small arms –it finds it difficult to avoid the descentinto chaos and the public violencethat must finally be recognized as war.Counting the warsSince 1987 <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>(<strong>2010</strong>a) has been tracking globalarmed conflicts and issuing annuallyan Armed Conflicts Report. In 1987,there were 37 wars taking place on theterritories of 34 states – Indonesia,the Philippines, and Iran were eachthe scene of two separate armed conflicts.Twenty-three years later, 2009ended with a total of 28 wars on theterritories of 24 countries – with thePhilippines and Sudan both the sceneof two separate wars, while Indianterritory hosted three armed conflicts.That is a welcome 25 per centdrop in the number of active armedconflicts, but it is a decline that masksa dynamic quarter-century of publicviolence and war in which many newwars began as others were ending.In addition to the 37 conflictsunder way in 1987, 44 new conflictsbroke out in the ensuing 23 years, fora total of 81 separate wars during thisperiod. Of those, 58 were resolved,but in 11 of those cases the peacedidn’t last and war resumed (of the11 resumed wars, six subsequentlyended). All told, the planet thushosted a total of 92 wars during thelast quarter-century.Not only do some conflicts reignite,but wars generally last a longtime. Fully one-third of the conflictsunder way in 1987 remain activetoday. Of the current 28 conflicts,only six are less than a decade old.Six have been under way for morethan three decades, another seven formore than two decades, and nine formore than one decade.A child pauses briefly with a toy in a camp forinternally displaced persons in Minova, DRC.© Aubrey Graham/IRIN.3The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

wars. Criminal organizations employviolence in the pursuit of profit, notin pursuit of a political program. Andwhile groups engaged in politicallydriven combat often pursue criminalactivities for economic gain, the morebasic objective of such groups, andthe basic point of the violence theypractise, is still the pursuit of militaryand political goals (Ballentine &Nitzschke 2005, pp. 4-5).4Internally displaced Congolese women wait during a food distribution in Kibati,just outside the eastern provincial capital of Goma. © Les Neuhaus/IRIN.When public violencemeans warWhile war is eminently recognizable,defining it is not so simple. Becausecontemporary wars are not declaredand because, in most cases – especiallycivil/intrastate wars — they donot follow from a clear or official decisionto go to war, it is often not at allobvious whether a country is “at war”or not. So, any effort to count warsmust obviously include the applicationof some reasonably objective,measurable criteria for determiningwhen a war begins and when it ends.The tabulation of wars for theannual <strong>Ploughshares</strong> ArmedConflicts Report (<strong>2010</strong>b) is based 2on three characteristics:• It is a political conflict;• It involves armed combat by thearmed forces of a state or the forcesof one or more armed factions seekinga political end, such as gainingcontrol of all or part of the state;• At least 1,000 people have beenkilled directly by the fighting duringthe course of the conflict.In many contemporary armedconflicts the fighting is intermittentand involves widely varying levels ofintensity. Afghanistan and Iraqexperience persistent and ongoingarmed clashes and attacks. Rwandawent from political tension tounprecedented levels of violenceand back down again in a relativelyshort period of time. The wars in thePhilippines and Burundi are examplesof ongoing but relatively low-levelconflicts, with annual combat deathsnow often as low as about 100 – but,of course, with political, economic,and social disruption well out ofproportion to the intensity of actionon actual battlefields.The definition of “political conflict”obviously cannot be technicallyprecise. Nevertheless the distinctionbetween political and criminal violenceis significant and discernable.There are clear instances in whichescalating violence that is clearlycriminal becomes so extensive that ittakes on significant political overtonesand complications. The Mexican drug“war” is perhaps the most prominentcase in point. The fundamentaldispute is clearly not political – it isa matter of organized crime – butthe impact on the country and onMexico’s relations with its neighbours,including the US, is such thatit engages government at the highestlevel, as well as the armed forcesof Mexico.Still, criminal violence remainsdistinct from the armed conflict ofwar, and Mexico is not included inthe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> count of currentTypes of warA relatively simple typology of armedconflict relies on four basic categories:international or interstate war plusthree overlapping types of intrastatewar (state control, state formation,and state failure). 3Interstate warsAn interstate war is a war betweentwo or more states and, for purposesof <strong>Ploughshares</strong> reporting, must alsomeet the 1,000-combat-death criterion.Though rare, international warsare not yet banished from history. Butthe distinction between interstate andintrastate violence is often obscured.Interstate wars are frequently foughton the territory of just one of thestates in the conflict –as in the 2001-2002 US-led attack on Afghanistanand the 2003 US-led attack on Iraq.On the other hand, it is obviouslyalso the case that virtually all civilor intrastate wars include extensiveinternational involvement.Intrastate warsThere are three basic types ofintra-state conflicts.State control wars obviouslycentre on struggles for control of thegoverning apparatus of the state. Statecontrol struggles are typically drivenby ideologically defined revolutionarymovements or decolonization campaigns,or are simply the means bywhich power transfers from one set ofelites to another. In some instances,communal and/or ethnic interests arecentral to the fight to transfer power;in other instances religion becomesa defining feature of the conflict; andin others the differences are moreideological.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

Armed Conflicts in Africa 1987-2009DatesType of Conflict*ConflictsBeganEndedResumedEndedINT SC SF FSAlgeria 1993 XAngola 1975 2002 XAngola (Cabinda) 2003 2005 XBurundi 1992 XChad 1965 X XCongo (Brazzaville) 1994 1995 1997 2000 XCongo (Kinshasa) 1990 X XCôte d’Ivoire 2002 2007 XGhana (land issues in north) 1994 1996 XGuinea 2000 2002 XEritrea/Ethiopia 1998 2000 XEthiopia 1974 1992 2003 X X XKenya 1993 XLiberia 1990 1996 2000 2003 XMozambique 1977 1993 XNamibia 1966 1989 XNigeria 1999 XRwanda 1990 1990 1992 2002 XSenegal 1999 2004 XSierra Leone 1994 2001 XSomalia 1986 X X X XSouth Africa 1966 2000 X XSudan (North/South) 1983 X XSudan (Darfur) 2003 X XUganda 1996 X XWestern Sahara 1975 1991 XZimbabwe (ZANU/ZAPU) 1982 1987 XTotal 27 17 4 3 2 18 7 11*Type of conflict: INT = interstate SC = state control SF = state formation FS = failed stateState formation wars centre on the form or shape ofthe state itself and generally involve particular regions of acountry fighting for a greater measure of autonomy or foroutright secession. Communal ethnic or religious claimsare frequently an element of such wars.Failed state wars are conflicts that are neither aboutstate control nor state formation, but are focused on morelocal issues and become violent in the absence of effectivegovernment control. The primary failure is in the lackof government capacity, or sometimes will, to provideminimal human security to groups of citizens. Pastoralistcommunities in East Africa, for example, usually live wellbeyond the reach of the state. There are virtually no statesecurity services or institutions present and no politicalmeans of mediating disputes over cattle raiding or accessto grazing lands and water. Communities come into conflict;with access to small arms, an escalation of violence isalmost inevitable. The violence is political, although it isover local issues and none of the parties has state-controlor state-formation objectives. Such conflicts are includedin the <strong>Ploughshares</strong> count when the threshold of 1,000combat deaths is reached.Of the 81 wars that occurred during the last 23 years,51 per cent included state control objectives, 35 per centincluded state formation objectives, 25 per cent reflectedfailed state conditions, and 11 per cent included interstatedimensions. 4The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>5

How wars endNo fewer than 64 wars ended during the past 23 years. Infive cases governments defeated rebels or insurgents. Infour cases the insurgents prevailed on the battlefield andhad their demands met.Thirty-three conflicts (52 per cent) ended throughnegotiated settlements. This does not mean that whathappened on the battlefield was not a significant factor inshaping the outcome. Military force certainly influencedor even determined the outcomes of negotiations. Forexample, in many cases rebel groups would never havegained a place at a negotiating table without an armedcampaign. But negotiators took over and reached apolitical conclusion.In the remaining 22 cases (34 per cent), the fightingessentially dissolved. While the conflicts were notresolved, the fighting gradually dissipated. In Guinea, forexample, fighting by the Revolutionary United Front wassupported by Liberia, but Guinea gradually persuadedboth Liberia and Sierra Leone to end their support of therebels, leading to a gradual decline in violence.War prevention a collective responsibilityIt is tempting to blame the current and still high levelsof internal or intrastate wars on the inability of states tobuild conditions that serve the social, political, and economicwelfare of their people. But those failures to achievehuman security at the national level are heavily shaped byexternal factors, notably the creation of international economicand security conditions that shift benefits prominentlytoward dominant economic and military powers.Thus war prevention, including the prevention of civilwars, is a collective international responsibility. And aworld in which 28 wars still rage, and in which the rapesof Luvungi are not an isolated horror, is a world that is notclose to meeting its responsibility.Notes1. More information about the number of rapes and orphans can befound on the UNICEF website: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/drcongo.html.2. This definition builds upon, but differs in some aspects from, annualconflict reports by the Department of Peace and Conflict Research atSweden’s Uppsala University (<strong>2010</strong>).3. These types were drawn from the Department of Peace and ConflictResearch at Uppsala University, although it does not now use them.4. The total is more than 100 per cent because 12 conflicts involved acombination of types.ReferencesBallentine, Karen & Heiko Nitzschke. 2005. The Political Economy ofCivil War and Conflict Transformation. Berghof Research Center forConstructive Conflict Management. http://www.berghof-handbook.net/documents/publications/dialogue3_ballentine_nitzschke.pdf.The Globe and Mail. <strong>2010</strong>. Prosecute to help stop rape inCongo. Editorial, September 4. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/opinions/editorials/prosecute-to-help-stop-rape-in-congo/article1700260/?cmpid=rss1.Kaufman, Stephen. <strong>2010</strong>. Clinton – Rape of civilians was ‘horrific attack’.AllAfrica.Com, August 26. http://allafrica.com/stories/<strong>2010</strong>08270260.html.<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>. <strong>2010</strong>a. Armed Conflicts Report 2009.http://www.ploughshares.ca/libraries/ACRText/ACR-TitlePage.html.———. <strong>2010</strong>b. Defining armed conflict. http://www.ploughshares.ca/libraries/ACRText/ACR-DefinitionArmedConflict.htm.Uppsala University. <strong>2010</strong>. Uppsala Conflict Data Program.http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/database.Ernie Regehr, O.C.,is Senior Policy Advisorwith <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>.6Check it out!The blog Disarming Conflict, launched in 2006 by<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> co-founder Ernie Regehr, has a newaddress: http://disarmingconflict.ca.“Disarming Conflict” explores “the initiatives, policies,and international rules that are designed to fulfill theUnited Nations’ Charter pledge to control and reducearsenals and to minimize and resolve armed conflict.”Recent posts examine the New Strategic Arms ReductionTreaty, Canada’s mission in Afghanistan after 2011, militarybudget cuts in the UK, and the proposed purchase byCanada of F-35 fighter jets.Ernie Regehr can be reached at eregehr@uwaterloo.ca.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>The Centre for the Study ofReligion and Peace is approvedIn October <strong>2010</strong> Conrad Grebel University College (CGUC)at the University of Waterloo established The Centre for theStudy of Religion and Peace. The Centre “aspires to advanceknowledge and awareness of religious contributionsto peace, and to enhance the capacity of religious communitiesto engage contemporary conflict issues and practise thepeaceful values they profess.”On November 11, the Centre conducted its first officialevent: Fear and Hope: Religion’s Role in Conflict andPeace, a colloquium featuring Dr. Luis Lugo, Director of thePew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life.The discussion was moderated by Dr. Nathan Funk, assistantprofessor of Peace and Conflict Studies at CGUC anda member of the Board of <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, and wasco-sponsored by <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, with <strong>Ploughshares</strong>Executive Director John Siebert welcoming the audienceand participants.

US contracts for combat systems during 2009Supplier Location Military product or service Contract value RecipientCAE Inc Montreal, QC HC/MC-130J aircraft full-mission simulator Not reported US Air ForceCMC Electronics Inc Montreal, QC AC-130 gunship aircraft mission display Not reported US Air ForceChicopee Manufacturing Kitchener, ON F-35 Lightning II JSF aircraft components u $67.6 million US Air ForceGeneral Dynamics Canada Nepean, ON Littoral Combat Ship construction work u Not reported US NavyGeneral Dynamics Land SystemsCanada CorpLondon, ON 902 Stryker combat vehicles work u $361 million US ArmyRepair battle-damaged mine protected vehicles $40.2 million US NavyGeneral Dynamics OTS Canada Le Gardeur, QC Work on 105mm artillery shells u Not reported US ArmyGeneral Electric Canada Bromont, QC F/A-18 fighter aircraft engine work u $4.8 million US NavyHéroux Inc Longueuil, QC B-1B bomber and other aircraft landing gear $11.3 million US Air ForceIMP Aerospace Components Ltd Amherst, NS Chinook heavy-lift helicopter components u $49 million US ArmyMagellan Aerospace Corp Mississauga, ON F-35 JSF aircraft horizontal tail components u $11 million US Air ForceMagtron Precision Scarborough, ON F-35 JSF aircraft electronic components u $10 million US Air ForceNGRAIN (Canada) Corp Vancouver, BC AC-130 gunship aircraft training package Not reported US Air ForceRaytheon Canada Ltd Waterloo, ON Work on Seasparrow missiles & containers u $31 million US NavyStandard Aero Ltd Winnipeg, MB Landing Craft marine engines $39.1 million US Navyu Subcontract with corporate prime contractor*Estimated contract valueSource: Canadian Military Industry Database, <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>India-Pakistan relationsand the impact on AfghanistanRussiaNicole WaintraubAfghanistanPakistanIndiaThere is widespread acknowledgmentof the profound influence thatAfghanistan-Pakistan ties have onthe prospect for long-term stability inAfghanistan. But we must expand thisunderstanding to include the role ofPakistan-India relations. Pakistan’slongstanding conflict with India andsuspicion of its regional engagement,especially in Afghanistan, havealready adversely affected the securitysituation. While there have beenencouraging recent developmentsbetween Afghanistan and Pakistan,Pakistan’s suspicion of India threatensto entrench relations of conflictand competition at the expense ofcooperation and stability.India’s involvementin AfghanistanThere are several ways to read India’scurrent engagement with Afghanistan.Since the overthrow of the Taliban,India has invested heavily in renewingits ties with Afghanistan. At present,India is the largest regional donor toAfghanistan’s reconstruction, havingoffered more than $1.2-billion (US)since 2001. This can be seen as acontribution toward greater regionalstability.India has been involved in variousreconstruction and capacity-buildingprojects, including major infrastructuredevelopment initiatives; women’semployability programs; medicalmissions; children’s health and schoolfeeding program delivery; and trainingfor civil servants, police, and diplomats.India has also strengthenedits economic ties with Afghanistan tothe extent permitted by the transitlimitations between the two countries.Such involvement has contributedgreatly to a positive public perception13The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

14An Afghan worker from Kandahar Citytakes a moment from mixing mortarfor a building project. Credit: MasterCorporal Angela Abbey / CanadianDepartment of National Defence.of India in some regionsof Afghanistan.India’s growinginvolvement inAfghanistan can also beseen as advancing morespecific strategic goals.For one, Afghanistan isgeographically positionedto serve as a viable accessroute for energy comingfrom Central Asia. Thisis increasingly importantas India takes steps tofoster greater energycooperation in the region,including a signed memorandumof understandingwith Turkmenistan todevelop a natural gaspipeline (Gundu &Schaffer 2008).One of India’s majorinfrastructure initiativeshas been to constructa highway linkingAfghanistan’s ring roadto Iranian ports on thePersian Gulf. This highwaycould effectivelyreduce, if not eliminate,Afghanistan’s currentdependence, as a land-locked state, on Pakistan for seaaccess (Rubin & Rashid 2008).Where does Pakistan fit?Some also see India’s involvement in Afghanistan as aneffort to displace or counterbalance Pakistan’s influence inthe country, which some elements within Afghanistan welcome(Bajoria 2009). India has strong ties to the so-calledNorthern Alliance. Many of its leaders were educated inIndia, including Afghan President Hamid Karzai (Bajoria2009).As India’s power in Afghanistan expands, especiallyits soft power, Pakistan is losing its position of economicand strategic privilege. In its place is a power with possiblyhostile intentions against it. For example, India’s reconstructionand development projects through Afghanistan’sPashtun belt are seen as ways of fomenting separatistmovements in Pakistan.Pakistan sees India’s growing influence, particularlyits consular presence in Afghanistan, as a threat. Shortlyafter the fall of the Taliban, India reestablished severalconsulates. While India has legitimate consular interestsin Afghanistan – Hindu and Sikh populations, commercialrelations, and aid programs – there is some speculation byPakistan that India has also been using these consulatesas a cover for its intelligence agencies to carry out covertoperations. Islamabad believes that India is colluding withAfghan officials to stoke Baloch separatism in Pakistan(Gundu & Schaffer 2008).There have been small successes in resolving someconcerns. The Pakistan Foreign Office is said to havestated in Parliament that they had received informationon the staffing of Indian consulates in Afghanistan and nolonger suspected India of using its consulates as bases forcovert activities (Delhi Policy Group 2009). What’s more,some retired Pakistani officials are willing to state, off therecord, that it is to be expected that any country will havesome operatives based in consulates and that the reactionto this in Pakistan has been disproportionate to the actualthreat.Strategic depth andencirclement in South AsiaFor decades India and Pakistan have contended forfavourable positions within Afghanistan. Throughoutthis struggle, Pakistan has seen Afghanistan as a vitalsource of “strategic depth.” In early <strong>2010</strong>, General Kayani,Pakistan’s Chief of the Defence Staff, stated that “a peacefuland friendly Afghanistan can provide Pakistan a strategicdepth” (Hussain <strong>2010</strong>). Though the meaning of thisterm has changed over time, its persistence in Pakistan’sstrategic vocabulary evokes Pakistan’s perception of relationswith Afghanistan as a way to defend against otheroutside forces. Although Gen. Kayani was clear that“strategic depth” must not be confused with “control,”Afghans remain highly sensitive to such language.Pakistan’s military establishment has long viewed itsengagement in Afghanistan largely from the context ofits struggle against India. Thus India’s growing presencein Afghanistan contributes to Pakistan’s fears of encirclement.India’s establishment of its first overseas air basein nearby Farkhor, Tajikistan has further aggravated suchfears (Gundu & Schaffer 2008).Afghan employees from Kandahar City build a new Afghan NationalPolice Training Centre. Credit: Master Corporal Angela Abbey / CanadianDepartment of National Defence.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

Pakistan’s behind-the-scenessupport for the Taliban is believedto be rooted, in large part, in itsconcern that India is attempting toencircle it by gaining influence inAfghanistan. The Taliban is thoughtto offer Pakistan its best chance atneutralizing India’s regional powerexpansion (Pakistan Policy WorkingGroup <strong>2010</strong>). This support has led toincreased instability in Afghanistan,both through heightened terroristactivity and increased opium cultivation(Bajoria 2009). It has also furthercomplicated the international effortsat reconstruction as well as intensifiedthe strain on the already tenuousAfghanistan-Pakistan relationship.As calls for a ‘Grand Bargain’ increasinglyinclude the Taliban, Pakistan’sties with its various strands willbecome all the more relevant.Some commentators have referredto Afghanistan and Pakistan as “conjoinedtwins,” not simply because oftheir complicated history, but alsobecause the ties between the two havebrought about many adverse effects.Consider, for example, the securitythreats linked to the porous borderand the significant costs that Pakistanhas taken on in accommodatingmillions of Afghan refugees.Looking forwardThis past summer saw some encouragingdevelopments. In July, as aresult of high-level talks, HamidKarzai announced that a group ofmilitary officers would travel toPakistan for training. This representsa significant symbolic shift inrelations between the two countries.In that same month Pakistan andAfghanistan finalized a transit tradeagreement, which would allow thetransport of goods along a land routethrough Pakistan to India.While these developments constituteimportant modifications ineach country’s position, they must beviewed in light of longstanding strategicpriorities and fears, especiallythose of Pakistan. If Pakistan stillbelieves that it is facing a perpetuallyhostile regional security environment,enduring peacebuilding strategies arenot likely to emerge.The greatest challenge lies inachieving cooperation between Indiaand Pakistan in Afghanistan. Thiswould require that India and Pakistanovercome longstanding political andpsychological barriers (Maley 2009,p. 90) through direct engagement. Ata minimum, they could discuss howbest to stay out of each other’s wayin Afghanistan. More ambitiously,they could usefully engage in a discussionof the best channels – bilateral,trilateral, or regional – throughwhich to address various governancechallenges. This discussion couldalso identify modest ways in whichIndia and Pakistan might align theirefforts, if not collaborate in achievingcommon goals. The initiation offormal engagement could chart theway to improved and increasinglytransparent relations and ultimately amore stable Afghanistan.Many experts and expert bodieshave pointed out that an opportunityexists to move forward on a richagenda of regional cooperation onmatters, including water management,energy security, and economiccooperation. 1 But the parameters offuture cooperation are being set nowthrough the bilateral maneuveringsof regional players, most importantlyIndia and Pakistan.Note1. See, for example, Maley 2009.ReferencesBajoria, Jayshree. 2009. India-Afghanistanrelations. Council on Foreign RelationsBackgrounder, July 22. http://www.cfr.org/publication/17474/indiaafghanistan_relations.html.Delhi Policy Group. 2009. Afghanistan-India-Pakistan Trialogue: A Report. www.delhipolicygroup.com/pdf/Final%20Book%20-%20Afgh-Ind-Pak.pdf.Gundu, Raja Karthikeya & Teresita Schaffer.2008. India and Pakistan in Afghanistan:Hostile spots. CSIS South Asia Monitor. #117,April 3. http://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/sam117.pdf.Hussain, Zahid. <strong>2010</strong>. Kayani spells out termsfor regional stability. Dawn.com, February 2.http://news.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/news/pakistan/06-pakistan-does-not-want-to-controlafghanistan-kayani-rs-02.Maley, William. 2009. Afghanistan and itsregion. In The Future of Afghanistan, editedJ. Alexander Thier, USIP: Washington, DC.Pakistan Policy Working Group. 2008. TheNext Chapter: The United States and Pakistan.http://www.brookings.edu/reports/2008/09_pakistan_cohen.aspx.Rubin, Barnett R. & Ahmed Rashid. 2008. Fromgreat game to grand bargain. Foreign Affairs,87:6, pp. 30-44.15Afghan employees from Kandahar City dig a trench to lay piping for the movementof potable water.Credit: Master Corporal Angela Abbey / Canadian Department ofNational Defence.Nicole Waintraubis an intern with<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

Brinksmanship, delayand broken agreementsThe Southern Sudan independence referendumJohn SiebertIt was under a tree in a dusty field in Southern Sudan in September 2008. The research interview was over, but the truckto take us to lunch hadn’t arrived. They asked me to sing a Canadian song. But what? I asked myself.These were 15 young men, mostly in their twenties. They had all recently returned to Tonj East County in WarrapState after having been displaced during the latest phase of the Sudan civil war (1983-2005).There was no way I was going to sing the Canadian national anthem. Too clichéd. Then I remembered the CBC radiocontest to determine the greatest Canadian song.So I sang the chorus of “Four Strong Winds.” Despite their English training in Kenya and Uganda, my listeners couldnot understand what the song was about. With all due respect to Ian Tyson, how could they? To outsiders the lyrics are astring of metaphors and romantic, poetic nonsense.Then I asked them to sing me a song. It took several minutes of consultation in Dinka to decide. What they sang camein gusty unison with much pointing and broad arm gestures. It was like a rah-rah song a group of guys might sing afterthe game on the way to the pub.So I interpreted my song – it’s about a man leaving a woman – and they interpreted theirs. It was a SouthernSudanese fight song, which said, in effect, that even if the North killed every last Southerner in Sudan, a pen wouldsurvive to write the story.I told them I liked my song better. It was about loving a woman. Smiles and knowing chuckles broke out all round,and we were off to lunch.16Southern dreamsIt’s difficult for those of us watching from afar toappreciate how deeply the hopes and dreams of SouthernSudanese are connected to the referendum on secessionslated for January 9, 2011. The most recent phase offighting with the North followed a decade-long hiatusof a civil war that has been fought since Sudan gainedindependence in 1956. But the conflict’s roots go muchdeeper in Sudan’s history.For most Southern Sudanese, the referendum is theprimary and final set piece of three set out in the 2005Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), after a sixyearinterim period in which both the North and theSouth formally committed themselves to “making unityattractive.” Oppressed even in the colonial period bythe primarily Arab and Muslim North that continuesto advocate for the application of sharia law across thecountry, the heavily Christian and African South hasfought, negotiated, and organized itself for one goal:independence.Commentators acknowledge that a fair and wellorganized referendum would result in an overwhelmingvote by Southerners for independence. And there is therub. The previous two major markers leading to January’sreferendum were the census in 2008 and elections in<strong>2010</strong>. The census and election processes were not good.But they were good enough, setting the stage for the finalact: referendum.Juba in Southern Sudan. <strong>Ploughshares</strong> photo.Delay tactics or new preparations for war?With six years’ lead time, you would think there wouldbe plenty of time to get ready, but apparently not. Itseems that the National Congress Party government inKhartoum, headed by International Criminal Court-The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

A Sudanese child drives a donkey cart through the market of Abyei, Sudan. © Peter Martell/IRIN.indicted President Omar al-Bashir,has nothing to gain by holding thereferendum. Khartoum’s actionsin the days leading up to January9 have been characterized quitenicely as “brinksmanship, delay andbroken agreements – old traditions ofSudanese politics” (Verjee <strong>2010</strong>, p. 9).Northern calls to delay thereferendum have been met by hintsof a resulting unilateral declarationof independence and readiness toreturn to war from the South. Thereis a reported military buildup by bothsides along the North-South borderthat cannot be adequately patrolledby the limited number of UN troopsalready in the country to facilitatethe implementation of the CPA. Inthe meantime, there are constantrumours of war.Much that should already havebeen done has not been. The North-South border is not demarcated.The state of Abyei is to have its own,separate referendum on whether itwants to belong to the North or theSouth. Yet quiet negotiations hostedin Ethiopia have not cleared the wayfor the Abyei vote to take place atthe same time as the wider vote onseparation.Like a conflict-inducing curse,Sudan’s primary foreign exchangeearner, oil, is largely located in theSouth or in the disputed North-Southborder region. Pipelines and refineriesare all to the North. While revenuesfrom oil extraction have been sharedby the North with the South duringthe six-year interim period, there isno guarantee of mutual cooperation ifthe South goes its separate way.The international community,led by US President Obama (Copnall<strong>2010</strong>) and Secretary of State HillaryClinton (Quinn <strong>2010</strong>), are outliningfor Khartoum a range of carrots andsticks designed to prevent politicaland technical difficulties from turninginto a national disaster.Apocalypse ora dream fulfilled?Apocalypse: the final revelation. Theword is often misused, but properlyunderstood it captures the moodof the people of Southern Sudan,and their family and friends in thediaspora, including those in Canada.Over two million people died in thelast phase of the civil war. The youngmen, for whom I sang “Four StrongWinds” in 2008, were a mere drop inthe bucket of four million Sudanesedisplaced in the same period.The referendum period has themarkers of apocalypse: a convictionby the South that good will finallytriumph decisively in the presentevil age and vindicate their suffering.Their oppressors in the North willbe isolated to their own fate by theestablishment of a new country inSouthern Sudan.What we know about apocalypseand dread is that hopes and dreamseasily become nightmares and untolddestruction. If civil war betweenNorth and South does return as aresult of the referendum – or its delay– its consequences will certainly becatastrophic. The last six years havegiven Southern Sudan the time andmeans to vastly improve its militarycapabilities (McEvoy & LeBrun <strong>2010</strong>).The previously dominant tactics ofguerrilla war will be supplementedwith more destructive battles usingmechanized conventional armaments.Let’s hope for the sake of allSudanese that the referendum takesplace, that it is good enough, and thatthe results allow Southern Sudan tomove forward while relegating itsfight songs to the past.ReferencesCopnall, James. <strong>2010</strong>. Barack Obama pressesfor peaceful Sudan referendum. BBC News,September 25. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11403968.McEvoy, Claire & Emile LeBrun. <strong>2010</strong>.Uncertain Future: Armed Violence in SouthernSudan. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/pdfs/HSBA-SWP-20-Armed-Violence-Southern-Sudan.pdf.Quinn, Andrew. <strong>2010</strong>. Clinton calls Sudanreferendum ‘ticking time-bomb’. Reuters,September 8. http://in.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-513714<strong>2010</strong>0908.Verjee, Aly. <strong>2010</strong>. Race Against Time:The countdown to the referenda in SouthernSudan and Abyei. London: Rift Valley Institute.http://www.sudantribune.com/IMG/pdf/Race_Against_Time_-_Aly_Verjee_-_30_Oct_<strong>2010</strong>-2.pdf.John Siebertis Executive Directorof <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>.17The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

From START to zeroThe importance – and limitations –of the New Strategic Arms Reduction TreatyCesar Jaramillo18The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START),signed by US President Obama and Russian PresidentMedvedev in April <strong>2010</strong> but not yet ratified, furtherreduces the strategic nuclear arms limits of previousbilateral treaties and institutes a more robust verificationregime. While the provisions of this treaty fostermuch needed transparency between the United States andRussia, it is far from a definitive step toward completenuclear disarmament. Not only does New START continueto recognize nuclear deterrence as a legitimate securitydoctrine, but the numbers of strategic nuclear weaponsstill allowed dwarf those of any other country and continueto constitute a clear and present threat to global security.BackgroundAs the Cold War was drawing to an end in the late 1980s,the United States and Russia engaged in a series of negotiationsto reduce and limit their nuclear arsenals, culminatingin the signing of the Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty(START) in 1991 and its subsequent ratification in 1994.Unlike previous arms control agreements between the twoCold War superpowers such as the 1972 Strategic ArmsLimitation treaty (SALT), which only restricted the futureproduction of new delivery vehicles, START provided forthe reduction of existing deployed warheads.START allowed the US and the Soviet Union (subsequentlyRussia) to each deploy up to 6,000 nuclearwarheads and 1,600 delivery vehicles (such as bombersand land- and submarine-based ballistic missiles).Any deployed weapons in excess of these numbershad to be taken off deployment as part of the treaty’simplementation.Besides the obvious benefit of significantly restrictingthe number of warheads, START contained a robust verificationprotocol to ensure compliance with the treaty. Thisfostered an unprecedented climate of increased transparencyand relative predictability with regard to the nuclearweapons capabilities of the signatories. Indeed, “that treaty’sverification measures allowed for a fuller understandingof [nuclear] forces than previous agreements, and thisin turn led to increased stability and cooperation betweenthe two countries” (Union of Concerned Scientists <strong>2010</strong>c).The Treaty Between the United States of America andthe Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions(SORT), also known as the Moscow Treaty, was signedin 2002 and set a new limit for each country of 2,200deployed strategic nuclear warheads. However, SORT hasbeen the subject of much criticism for its lack of verificationprovisions to ensure that agreed-to reductions havein fact taken place. Thus, the December 2009 expirationof the 1991 START marked the end of the verification protocolsand, for the first time in more than two decades,inspection teams from the US and Russia were unableto physically verify the number and operational statusof each other’s strategic nuclear forces. This increasedthe likelihood of misunderstandings and potential frictionin what is perhaps the most sensitive of arms controlregimes. To fill this void, Obama and Medvedev signed theNew START.Key provisions of New STARTNew START sets limits on nuclear warheads and deliveryvehicles that are well below those imposed by the 1991START treaty. These limits are to be met within sevenyears of treaty ratification by Russia and the US.Specifically, the primary limits for each countryincluded in the New START treaty (Gottemoeller <strong>2010</strong>)are:• A maximum of 700 deployed intercontinental ballisticmissiles (ICBMs), deployed submarine-launched ballisticmissiles (SLBMs), and deployed nuclear-capableheavy bombers;• A maximum of 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads placedin the abovementioned delivery vehicles;• A maximum of 800 deployed and non-deployed ICBMlaunchers, SLBM launchers and nuclear-capable heavybombers.The number of warheads and delivery vehicles that eachcountry is permitted to possess under this treaty, whilestill significant, is considerably lower than what wasallowed under previous bilateral treaties. Indeed, the limiton warheads is approximately 75 per cent lower than thatof START (from 6,000 to 1,550 warheads) and about 30per cent lower than the Moscow Treaty (from 2,200 to1,550). The limit on deployed delivery vehicles allowedunder START is cut by more than half (from 1,600 to 700).However, current levels of strategic nuclear forcesin the US and Russia are already remarkably close tothe New START levels. Although estimates vary, recentThe <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>helps shape thedebate on the F-35Joint Strike Fighteraircraft controversyIn the last few months the proposed purchase by theCanadian government of F-35 Joint Strike Fighter aircrafthas been the subject of ongoing public discussion and debatein the Canadian media and in the House of Commons.<strong>Ploughshares</strong>’ response has helped to shape the debate.• August 12: <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Briefing 10/3. Why Joint Strikeaircraft? Program costs rise and benefits carry risks by<strong>Ploughshares</strong> Senior Program Associate Kenneth Epps.• August 24: Globe and Mail article, “Critics set to launchnew attacks on untendered deal to buy fighter jets,” quotesextensively from Briefing 10/3.• August 25: Epps appears in Global TV news coverage ofthe F-35 and Prime Minister Harper’s visit to the CanadianNorth. Epps is also interviewed on “Afternoon Newswith Tom Young” on News 95.7 radio.• August 29: <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Executive Director JohnSiebert is interviewed by Mike Blanchard on the nationallysyndicated radio program The Roy Green Show on theJoint Strike Fighter purchase.• September 15: Siebert and Epps address the Houseof Commons Standing Committee on National Defenceabout the proposed purchase by Canada of 65 Joint StrikeFighter F-35 aircraft.• October 4: “Parliamentary review of new fighter aircraftneeded” by Kenneth Epps in Autumn <strong>2010</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>Monitor.• November 4: <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Briefing 10/4. The size ofthe F-35 market is overstated by Kenneth Epps.• November 5: Reference to Briefing 10/4 in Globe andMail article, “F-35 ‘glitches’ won’t affect Canadian fighterjet order, MacKay says.”• November 6: Reference to Briefing 10/4 inDavid Pugliese’s Defence Watch.StafftransitionsIn November Christina Woolner begana three-year appointment with <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong> as <strong>Project</strong> Officer. Herprincipal role will be to support theimplementation of our project tostrengthen cooperation in Caribbeancountries to reduce gun crime, but shewill also work on other <strong>Ploughshares</strong>projects and programs.Christina has an MA in International Peace Studiesfrom Notre Dame University and a BA from WilfridLaurier University in Global Studies and Religion andCulture. As a <strong>Ploughshares</strong> intern she worked on theArmed Conflicts Report. She has also worked in SouthAfrica and Russia. 21The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

22Invest inpeaceIn advance of the G8 Summit in Muskoka, 80 leaders ofthe world’s religions and faith-based organizations convenedin Winnipeg and issued a closing statement. Here isan excerpt. (For the full statement, go to www.faithchallengeg8.com.)The well-being and shared security of all can only be realizedwhen grounded in justice. Shared security focuses onthe fundamental inter-relatedness of all persons and theenvironment (World Religions Summit, Sapporo 2008).Civilians in the world’s poorest countries are the primaryvictims of war, insurgencies, criminal activities and otherforms of armed violence. At the same time, we are collectivelyaffected and implicated in global turmoil throughour common humanity and through the priorities we set.One clear example of misplaced priorities is globalmilitary spending, estimated to be US$1,464 billion for2008, while support for United Nations peace-keepingoperations is only US$9 billion. NATO countries accountfor over two-thirds of this global military spending;these payments for military services are more than 20times the annual world financial contributions to OfficialDevelopment Assistance. Another example of misplacedpriorities is the continuing threat of nuclear weapons andother weapons of mass destruction that represent a moralaffront to human dignity and a grave danger to life.We are aware that there are those who use religion tojustify violent acts against others, and thereby offend thetrue spirit of their faith and the long-standing values oftheir faith communities. We condemn religiously motivatedterrorism and extremism and commit to stop theteaching and justification of the use of violence betweenand among our faith communities.In <strong>2010</strong>, we expect inspired leadership and actionsthat invest in peace!• We call on governments to halt the arms race, makenew and greater investments in supporting a culture ofpeace, strengthen the rule of law, stop ethnic cleansingand the suppression of minorities, build peace throughnegotiation, mediation, and humanitarian supportto peace processes, including the control and reductionof small arms that every year are the cause of over300,000 deaths globally.• We call on states with nuclear weapons to make immediateand substantial cuts in the number of nuclearweapons and to cease the practice of having nuclearweapons on hair-trigger alert. Let these be the initialsteps in a defined process leading to the complete andpermanent elimination of nuclear weapons.• We call for the establishment of transparent and effectivedialogue mechanisms between international organizationsand faith communities that takes advantage of thepeace-making potential of religion.Binalakshmi Nepramreceives Sean MacBridePeace PrizeBinalakshmi Nepram, founder of Manipur Women GunSurvivors Network and Secretary-General of ControlArms Foundation of India (CAFI), has been awardedthe Sean MacBride Peace Prize for <strong>2010</strong>. During 2009and <strong>2010</strong> Nepram and CAFI partnered with <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong> to advance support for the Arms TradeTreaty in India with funding from the UK Foreign andCommonwealth Office.The prize, awarded annually by the InternationalPeace Bureau, was given to Nepram in recognition of her“pioneering work,” which has demonstrated, in particular,“the linkage between disarmament and development.” Inher acceptance speech, Nepram called upon people, organizations,and nations around the world to rally for peaceand justice in some of the world’s forgotten areas.Canadian Schoolof Peacebuilding:Courses for 2011Details of the courses to be offered by the CanadianSchool of Peacebuilding in June 2011 are nowavailable. A brochure can be downloaded by goingto http://www.cmu.ca/csop/pdfs/csopbooklet.final.pdf.CSOP is housed at the Canadian MennoniteUniversity in Winnipeg. Courses are available forprofessional development or academic credit andare open to members of all faith groups.The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

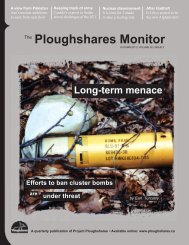

ResourcesCountdownto Zero, a newfilm by documentarianLucyWalker (Devil’sPlayground,Blindsight),traces thehistory of theatomic bomb from its origins toa present in which nine nationspossess nuclear weaponscapabilities while others raceto join them. It explores thedangers of these weapons,exposing a variety of currentthreats and featuring insightsfrom a host of internationalexperts and world leaders whoadvocate total nuclear disarmament.The documentary, aMagnolia Pictures release, isnow available in Blu-Ray andDVD formats.Ending Wars,ConsolidatingPeace:EconomicPerspectives,edited byMats Berdaland AchimWennmann,Routledge, <strong>2010</strong>, ISBN 978-0-415-61387-3, paperback, 258pages, $19.95.Ending Wars, ConsolidatingPeace presents a series ofeconomic perspectives onconflict resolution to show howpeacebuilding can be moreeffectively tackled. It considershow economic factors canpositively shape and drive peaceprocesses.Among its 10 chapters are thefollowing:• “Stabilising Fragile States andthe Humanitarian Space” byRobert Muggah• “Assessing Linkages BetweenDiplomatic Peacemaking andDevelopmental PeacebuildingEfforts” by Ashraf Ghani, ClareLockhart, and Blair Glencorse• “Valuable Natural Resourcesin Conflict-Affected States” byPäivi Lujala, Siri Aas Rustad,and Philippe Le Billon• “Crime, Corruption andViolent Economies” by JamesCockayne.Mats Berdal is Professor ofSecurity and Development in theDepartment of War Studies atKing’s College, London. AchimWennmann is a Researcherat the Centre on Conflict,Development and Peacebuildingof the Graduate Institute ofInternational DevelopmentStudies in Geneva.StrategicSurvey <strong>2010</strong>:The AnnualReview ofWorld Affairs,by InternationalInstitute forStrategicStudies,Routledge, <strong>2010</strong>, ISBN 978-1-85743-563-4, paperback, 400pages, $205.00.The Strategic Survey is theannual review of world affairsfrom the International Institutefor Strategic Studies. Its key elementsare Events-at-a-Glancechronology; “Perspectives,”an assessment of the effectof major events and trends onthe strategic landscape; andregional and thematic chaptersthat examine particular strategicpolicy issues, such as terrorismand weapons of mass destruction,missile defence, and thefuture of peacekeeping.Strategic Survey <strong>2010</strong> featuresthree specially commissionedessays for <strong>2010</strong>:• US Nuclear Policy Transformed• US Defence Policy: Preparingfor Change• Europe’s Evolving SecurityArchitecture.The Strategic Survey concludeswith “Prospectives,” an essaysetting forth strategic prioritiesfor the coming year. Alsoincluded are 32 pages of maps.TowardsNuclear Zero, byDavid Cortrightand RaimoVäyrynen,Routledge<strong>2010</strong>, ISBN978-0-415-59528-5,paperback, 182 pages, $19.95.Towards Nuclear Zero examinespractical steps for achievingprogress toward disarmament.The current debate over nuclearabolition is placed in the contextof urgent non-proliferation prioritiesand the need to preventnuclear weapons from fallinginto the hands of extremistregimes and terrorists. It examinesthe reasons why more thantwo dozen states have given upnuclear programs over the yearsand distills lessons from the endof the Cold War to offer policyrecommendations for movingtoward lessened global relianceon nuclear weapons.The book concludes witha detailed roadmap to globalnuclear zero. It proposes anew international securityregime based on shared missiledefences, nonweaponizeddeterrence, and greaterefforts to enhance transnationalcooperation.David Cortright is Directorof Policy Studies at the KrocInstitute for International PeaceStudies at the University ofNotre Dame and chair of theFourth Freedom Forum. RaimoVäyrynen is former Directorof the Finnish Institute ofInternational Affairs.SIPRIYearbook <strong>2010</strong>:Armaments,DisarmamentandInternationalSecurity, byStockholmInternationalPeace Research Institute,Oxford University Press, <strong>2010</strong>,ISBN 978-0-19-958112-2, hardback,580 pages, $185. For thefirst time, full text is availableonline; see www.sipriyearbook.org to order online or printeditions.The 41st edition of the SIPRIYearbook analyzes developmentsin 2009 in• Security and conflicts• Military spending andarmaments• Nonproliferation, arms control,and disarmament.It contains extensive annexeson the implementation of armscontrol and disarmamentagreements and a chronologyof events during the year inthe area of security and armscontrol.This year’s highlights include:• an assessment of the practicalsteps that states must take ifthey are serious about nucleardisarmament by former USdiplomat and disarmamentexpert James E. Goodby• an expanded analysis of datareleased earlier in the year onthe top 100 arms-producingcompanies (excluding Chinesecompanies) and the latesttrends in international armstransfers• extensive appendices andannexes that provide furtherdata and documentation onmajor armed conflict andmultilateral peace operations,arms control andnon-proliferation.The Stockholm InternationalPeace Research Institute is anindependent international institutededicated to research intoconflict, armaments, arms controland disarmament.ClusterMunitionMonitor<strong>2010</strong>, ClusterMunitionCoalition, reportsupervisedby editorialboard fromMines ActionCanada (lead agency), Actionon Armed Violence, HandicapInternational, Human RightsWatch, and Norwegian People’sAid, ISBN: 978-0-9738955-6-8,236 pages, available at www.themonitor.org.The first Cluster MunitionMonitor was released November1, <strong>2010</strong>. This new publicationcovers cluster munition banpolicy, use, production, trade,and stockpiling for every countryin the world. It also includesinformation on cluster munitioncontamination, casualties, clearance,and victim assistance.Definition of cluster munitionsfrom the Preface:Cluster munitions consist ofcontainers and submunitions.Launched from the groundor dropped from the air, thecontainers open and dispersesubmunitions indiscriminatelyover a wide area. Many fail toexplode on impact, but remaindangerous, functioning like defacto antipersonnel landmines.Thus, cluster munitions putcivilians at risk both duringattacks due to their wide areaeffect and after attacks due tounexploded ordnance.<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> is a memberof Cluster Munition Coalitionand Mines Action Canada.23The <strong>Ploughshares</strong> Monitor I <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

YourLegacyfor PeaceYou’ve dedicated your life to peace.You can continue to make our worlda better place for generations tocome by making a bequest to <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong> through your will.Contact Nancy Regehrat 519-888-6541ext. 705 or nregehr@ploughshares.cawww.ploughshares.caI am proud to support <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and have included you as a beneficiary in my will.Keep up the good work! Joanne - Surrey, BCMonitor<strong>Winter</strong><strong>2010</strong>BequestAdCMYK.i1 126/11/<strong>2010</strong> 10:58:17 AMPUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40065122REGISTRATION NO. 11099RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSESTO PROJECT PLOUGHSHARESINSTITUTE OF PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIESCONRAD GREBEL UNIVERSITY COLLEGEWATERLOO, ONTARIO, CANADA N2L 3G6