Addressing Armed Violence in East Africa.pdf - Project Ploughshares

Addressing Armed Violence in East Africa.pdf - Project Ploughshares

Addressing Armed Violence in East Africa.pdf - Project Ploughshares

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

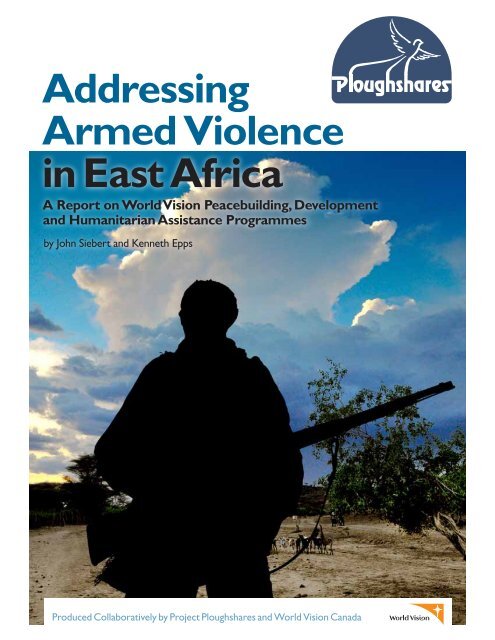

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>A Report on World Vision Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g, Developmentand Humanitarian Assistance Programmesby John Siebert and Kenneth EppsProduced Collaboratively by <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision Canada

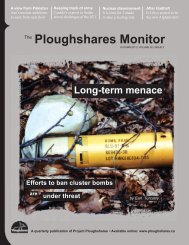

Founded <strong>in</strong> 1976, <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> is an operat<strong>in</strong>g agency ofThe Canadian Council of Churches with a mandate to work withchurches, governments, and civil society, <strong>in</strong> Canada and abroad, toadvance policies and actions that prevent war and armed violenceand build peace.For more <strong>in</strong>formation, please contact:John SiebertExecutive Director<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>57 Erb Street WestWaterloo ON N2L 6C2(519) 888-6541, ext. 702jsiebert@ploughshares.caWorld Vision is a Christian relief, development and advocacyorganisation dedicated to work<strong>in</strong>g with children, families andcommunities to overcome poverty and <strong>in</strong>justice. As followersof Jesus, we are motivated by God’s love to serve all peopleregardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender.For more <strong>in</strong>formation, please contact:Suzanne CherryResearch and Publications ManagerAdvocacy and EducationWorld Vision Canada1 World DriveMississauga, ON L5T 2Y4Tel. 905-565-6200, ext. 3148Suzanne_Cherry@worldvision.caFront cover photography by Jon Warren / World VisionCopyright © 2009 World Vision Canada

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>Table of ContentsAcknowledgements .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Acronyms and Abbreviations .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Jo<strong>in</strong>t Statementby <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision Canadaon Development, Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and<strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Reduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61. Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82. Research Methodology .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113. Kenya . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143.1. Apply<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>Lens to Kenya . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153.2. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>:The Impact of World Vision Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g .. . . . . . . . . 263.3. Observations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324. Uganda .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334.1. Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 344.2. Apply<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>Lens to Uganda .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 354.3. World Vision UgandaPeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Intervention .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 434.4. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>:The Impact of World Vision Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g .. . . . . . . . . 494.5. Observations .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 535. Sudan .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 555.1. Apply<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>Lens to Sudan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 565.2. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>:The Impact of World Vision Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g .. . . . . . . . . 645.3. Observations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 696. Conclud<strong>in</strong>g Observations .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Appendix 1: Interview Guide .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84Appendix 2: Glossary of Terms .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 861

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>AcknowledgementsThe authors wish to thank those people who agreed to be<strong>in</strong>terviewed for this report, people from communities <strong>in</strong> Kenya’sNorth Rift Valley, <strong>in</strong> Uganda’s Kitgum and Soroti districts,and <strong>in</strong> Southern Sudan’s Warrap State. These communitieswelcomed us and shared their <strong>in</strong>sights, despite the shorttimeframe with<strong>in</strong> which we conducted the research. Needless tosay, we were struck by the courage and resilience of the peoplewe met, and by their determ<strong>in</strong>ation to work for peace <strong>in</strong> theircommunities despite the numerous challenges encountered.This report was written by John Siebert and Ken Epps from<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>. <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> was ably assistedby Suzanne Cherry and Chris Derksen-Hiebert of WorldVision Canada, which funded the research. Suzanne Cherryworked closely with <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and WV <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>colleagues as they collectively developed the plan, methods andlogistics for the field research and reviewed the results. She alsojo<strong>in</strong>ed the field research teams <strong>in</strong> Kenya and Uganda.The research teams travelled <strong>in</strong> the safety and security of thetrust established <strong>in</strong> the communities by World Vision. We cameto greatly admire the deep concern World Vision staff br<strong>in</strong>g totheir work and their commitment despite the many risks theyface to carry it out.Travel with<strong>in</strong> northern Kenya, northern and eastern Ugandaand Southern Sudan would not have been possible without theextensive preparation and resources of World Vision nationaland local staff <strong>in</strong> each country. In particular, we are gratefulto Tobias Oloo (WV Kenya), Sar<strong>in</strong>a Hiribae (WV Kenya),Jackson Omona (WV Uganda) and Sarah Gere<strong>in</strong> (WV Sudan),for their role <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g the research design and plans, formak<strong>in</strong>g the arrangements <strong>in</strong>-country, for their participation<strong>in</strong> the field research and for their comments on report drafts.The support of numerous other field-level colleagues was<strong>in</strong>dispensable. In this regard, we would like to recognize MosesMas<strong>in</strong>de (WV Kenya), Marko Madut Garang (WV Sudan),Henry Muganga (WV Sudan), Joel Mundua (WV Uganda),and Tobby Ojok (WV Uganda).Other World Vision staff from around the world contributedtheir expertise to the project design and the review of its results.Our s<strong>in</strong>cere thanks are extended to the WV <strong>Africa</strong> RegionalOffice, <strong>in</strong> particular to Sue Mbaya and Valarie Vat Kamatsiko;to WV International Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g colleagues Bill Lowrey,James Odong and Krystel Porter; and to Denise Allen (WVInternational), Jonathan Papoulidis (WV Canada), Matt Scott(WV International) and Steffen Emrich (WV Germany).The content of the report has been reviewed by World Visionstaff <strong>in</strong> the three countries visited, <strong>in</strong> Canada and at the<strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> regional and WV <strong>in</strong>ternational levels – <strong>in</strong> part tom<strong>in</strong>imise the risk that quotations can be attributed to andpossibly endanger people <strong>in</strong>terviewed, who already daily facethe tw<strong>in</strong> threats of armed violence and economic uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty.John SiebertExecutive Director<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>57 Erb Street WestWaterloo ON N2L 6C2(519) 888-6541, ext. 702jsiebert@ploughshares.ca<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> is the ecumenical peace centre of The CanadianCouncil of Churches and affiliated with the Institute of Peace andConflict Studies, Conrad Grebel University College, University ofWaterloo, Canada.2

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>JON WARREN / World VisionAcronyms and AbbreviationsADP Area Development ProgrammeAVL <strong>Armed</strong> violence lensCEWARN Conflict Early Warn<strong>in</strong>g and Response MechanismCBO Community-based organisationCCM Comitato Collaborazione Medica (Italian NGO)CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement (Sudan)DC District Commissioner (Kenya)DDR Demobilisation, disarmament and rehabilitationDIPLCAP Disaster Preparedness and Local Capacities for PeaceDNH Do No HarmGD Geneva Declaration on <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> and DevelopmentGISO Gombolola Internal Security Officer (Uganda)GOSS Government of Southern SudanHDI Human Development IndexHQ HeadquartersIDP Internally displaced personIGAD Intergovernmental Authority on DevelopmentIPAD Integrat<strong>in</strong>g Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and DevelopmentKPR Kenya Police Reserve/ReservistKSh Kenyan shill<strong>in</strong>gLCP Local Capacities for PeaceLDU Local Defence Unit (Uganda)LRA Lord’s Resistance ArmyMSTC Mak<strong>in</strong>g Sense of Turbulent ContextsNAP National Action Plan on Small Arms and Light WeaponsNCCK National Council of Churches of KenyaNGO Nongovernmental organisationOCPD Officer Command<strong>in</strong>g Police Division (Kenya)OECD-DAC Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation forEconomic Co-operation and DevelopmentPEAP Poverty Eradication Action Plan (Uganda)MP Member of ParliamentRPG Rocket-propelled grenadeSALW Small arms and light weaponsSCC Sudan Council of ChurchesSDG Sudanese poundSPC Special Police Constable (Uganda)SPLA/M Sudan People’s Liberation Army/MovementSSRRC South Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation CommissionUNDP United Nations Development ProgrammeUNMIS United Nations Mission <strong>in</strong> SudanUPDF Uganda People’s Defence ForceUSh Ugandan shill<strong>in</strong>gWV World VisionWVC World Vision CanadaWVK World Vision KenyaWVS World Vision SudanWVU World Vision Uganda3

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>Jo<strong>in</strong>t StatementJo<strong>in</strong>t Statement by <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision Canadaon Development, Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Reduction<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision Canada are pleased to publish this report based on2008 field research <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> on armed violence reduction and World Vision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gand development activities. The research report itself attempts to faithfully document whatwas heard and seen dur<strong>in</strong>g the three weeks that <strong>in</strong>terviews were conducted <strong>in</strong> selected parts ofKenya, Uganda and Sudan. Observations are provided based on the research but conclusions andrecommendations were deliberately excluded from the report proper because of the constra<strong>in</strong>tsdescribed <strong>in</strong> the Methodology section.We will not be so reserved <strong>in</strong> this jo<strong>in</strong>t statement. The recommendations below are <strong>in</strong>tended tofocus discussion with and among donors, partner country governments, government foreign anddefence policy makers, colleagues <strong>in</strong> Northern and Southern non-governmental organisations(NGOs) and academic <strong>in</strong>stitutions on how the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> this report can and should beused to formulate policy and direct programm<strong>in</strong>g to advance development effectiveness andreduce armed violence. Our complementary mandates shape the recommendations. <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong>’ mandate is to identify, develop, and advance approaches that build peace andprevent war. World Vision’s mandate is to see every child experience life <strong>in</strong> all its fullness, as wework with children, families and communities to overcome poverty and <strong>in</strong>justice.Our research partnership arose from a common cause. The project was formed on the basis ofprior commitments <strong>in</strong> both organisations to contribute to the grow<strong>in</strong>g body of evidence-basedresearch document<strong>in</strong>g the important l<strong>in</strong>k between reduc<strong>in</strong>g armed violence and <strong>in</strong>creasedeffectiveness of peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g, development and humanitarian relief programm<strong>in</strong>g. World VisionInternational has made a world-wide organisational commitment to address<strong>in</strong>g violent conflict<strong>in</strong> its programm<strong>in</strong>g because without this cross-cutt<strong>in</strong>g focus, its work and <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> localcommunity development risk be<strong>in</strong>g underm<strong>in</strong>ed and even squandered. <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>’research and policy work to stop the uncontrolled proliferation of conventional arms—particularly small arms and light weapons—has <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly been focused on the demand factors<strong>in</strong> arms proliferation. Why do people believe that they need guns, and how do we f<strong>in</strong>d ways forpeople to feel safe without them? The answers generally come from development programm<strong>in</strong>grather than disarmament processes.In 2008, <strong>in</strong> an effort to assess the full scope and impact of worldwide violence, the Secretariat ofthe Geneva Declaration on <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> and Development published the Global Burden of<strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>. This study affirms that the more than 100 state signatories to the 2006 GenevaDeclaration “…recognize that effective prevention and reduction of armed violence requiresstrong political commitment to enhance national and local data collection, develop evidencebasedprogrammes, <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong> personnel, and learn from good practice.” 1This study offers one “brick” <strong>in</strong> what we trust will become a ris<strong>in</strong>g wall of field-based evidenceto advance best practices <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g armed violence. But other commitments also needimplement<strong>in</strong>g. The Geneva Declaration calls on signatories to “strengthen efforts to <strong>in</strong>tegratestrategies for armed violence reduction and conflict prevention <strong>in</strong>to national, regional, andmultilateral development plans and programmes.” 2 Hence, our recommendations:1 http://www.genevadeclaration.org/<strong>pdf</strong>s/Global-Burden-of-<strong>Armed</strong>-<strong>Violence</strong>.<strong>pdf</strong>, p.42 Ibid., p 4.4

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>Jo<strong>in</strong>t Statement1. That donor agencies, Southern and Northern NGOs and academics systematically <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong>armed violence reduction-related research, on:• The relationship between programm<strong>in</strong>g and conflict and how aid and conflict <strong>in</strong>teract;• Conflict-sensitive analysis of regions, sub-regions, countries, and local areas;• Basel<strong>in</strong>e conditions and post-<strong>in</strong>tervention results for long-term impact assessment;• Action-oriented research on field-level activity to derive “lessons learned” and “bestpractices”; and• The differential impact of armed violence on men, women and children.2. That donor agencies develop policy and fund programm<strong>in</strong>g on armed violence reduction, andthat these <strong>in</strong>corporate Southern and Northern NGO and academic expertise.3. That donor country armed violence reduction policies be grounded <strong>in</strong> their foreign and defencepolicy commitments on the control and reduction of small arms and light weapons.4. That donor agencies, NGOs and their local partners <strong>in</strong>clude provisions <strong>in</strong> their research andprogramm<strong>in</strong>g for protect<strong>in</strong>g children and other vulnerable groups from reprisals relatedto <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> armed violence reduction <strong>in</strong>itiatives, and seek to avoid other harmful,un<strong>in</strong>tended consequences of these <strong>in</strong>itiatives.5. That the OECD-DAC, other multilateral agencies, and country partners ensure the<strong>in</strong>corporation of armed violence reduction programm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to Poverty Reduction StrategyPapers, national poverty reduction programmes, and multilateral pooled fund<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms<strong>in</strong> order to strengthen commitment to implementation.6. That long-term susta<strong>in</strong>ed fund<strong>in</strong>g be committed by donor agencies to pilot projects or countryprogrammes l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g armed violence reduction and development, <strong>in</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ation withother countries and multilateral donors. These projects should ensure local ownership andparticipation <strong>in</strong> all phases of plann<strong>in</strong>g and implementation, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the development of andsupport to local research capacity and civil society participation. They should also take <strong>in</strong>toaccount and plan for address<strong>in</strong>g the particular needs and considerations of specific groups,such as those of women and of children.John SiebertExecutive Director<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>Chris Derksen-HiebertDirector of Advocacy and EducationWorld Vision Canada5

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>Executive SummaryDespite the harmful impact of armed violence on developmentprocesses, development assistance, peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g anddisarmament efforts have not systematically been l<strong>in</strong>ked.This is chang<strong>in</strong>g. An <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g number of developmentorganisations are mak<strong>in</strong>g these connections, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g WorldVision, whose experience is documented <strong>in</strong> this study.Aid delivered without sensitivity to conflict dynamics can makematters worse if underly<strong>in</strong>g tensions <strong>in</strong> a community are nottaken <strong>in</strong>to consideration, a pr<strong>in</strong>ciple underscored with<strong>in</strong> the“Do No Harm” framework developed by Mary B. Anderson.Furthermore, aid <strong>in</strong>vestments can be underm<strong>in</strong>ed or evensquandered if guns are be<strong>in</strong>g used to <strong>in</strong>jure and kill people,if <strong>in</strong>frastructure is be<strong>in</strong>g destroyed, if agricultural activity isbe<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>in</strong>dered, if access to markets is <strong>in</strong>terrupted, or if peopleare <strong>in</strong> a state of debilitat<strong>in</strong>g fear or are <strong>in</strong> flight from armedviolence.This cooperative study between <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> andWorld Vision Canada was undertaken to document howWorld Vision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and development <strong>in</strong>itiatives arecontribut<strong>in</strong>g to reductions <strong>in</strong> armed violence <strong>in</strong> selected areas of<strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>. The research was undertaken <strong>in</strong> September 2008 <strong>in</strong>the North Rift Valley <strong>in</strong> Kenya, the Kitgum and Soroti districts<strong>in</strong> Uganda, and <strong>in</strong> Warrap State <strong>in</strong> Southern Sudan.Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation forEconomic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC).This lens emphasises four elements relat<strong>in</strong>g to armed violence:affected populations, perpetrators, the <strong>in</strong>struments of violence,and the <strong>in</strong>stitutional or cultural environment. 2 While thecontext varied <strong>in</strong> the three countries visited, the field researchconfirmed that armed violence was a substantial h<strong>in</strong>drance todevelopment <strong>in</strong> each. In the communities visited <strong>in</strong> Kenya andSudan, armed violence is associated primarily with pastoralistcattle raid<strong>in</strong>g. In Uganda the situation is characterised by postconflictviolence <strong>in</strong> land disputes, crim<strong>in</strong>ality and domesticviolence.In all of the countries visited the primary perpetrators of armedviolence were consistently identified as males <strong>in</strong> the 15-30 yearold category. These young men were also the primary directvictims of armed violence through <strong>in</strong>jury and death dur<strong>in</strong>gcattle raids <strong>in</strong> Kenya and Sudan. This form of armed violencealso had consequences for children, women, older men andtheir communities: <strong>in</strong>jury and death, displacement from theirhomes, the loss of loved ones, the disruption of livelihoodsand school<strong>in</strong>g. In Uganda the violence was related to theft,domestic and sexual violence, and land disputes. Each of thecommunities visited suffered from lost collective wealth andopportunities to build or obta<strong>in</strong> shared <strong>in</strong>frastructure.This research report fits with<strong>in</strong> a wider discussion tak<strong>in</strong>gplace among development and disarmament actors onthe relationship between armed violence reduction anddevelopment processes. The 2006 Geneva Declaration on<strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> and Development states that: “Liv<strong>in</strong>g freefrom the threat of armed violence is a basic human need. Itis a precondition for human development, dignity and wellbe<strong>in</strong>g” and that “conflict prevention and resolution, violencereduction, human rights, good governance and peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gare key steps towards reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty, promot<strong>in</strong>g economicgrowth and improv<strong>in</strong>g people’s lives.” 1The study was designed and implemented cooperativelybetween <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision staff.While it is not a formal, external evaluation, it offers someprovisional and comparative observations about World Visionpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and development practices and their relationshipto reductions <strong>in</strong> armed violence. The research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs arepresented us<strong>in</strong>g the “armed violence lens” created for theThe gender dimensions of armed violence can be complex;for example, women were reported <strong>in</strong> limited cases to beperpetrators of armed violence, directly by us<strong>in</strong>g weapons,or <strong>in</strong>directly by encourag<strong>in</strong>g their sons to raid. Women weremore commonly reported to be important participants <strong>in</strong> peaceprocesses, with<strong>in</strong> all three countries.The most common <strong>in</strong>struments used <strong>in</strong> armed violence <strong>in</strong> theareas visited were variants of the AK-47. Ready availabilityof these automatic rifles was apparent <strong>in</strong> Kenya and Sudan.Their <strong>in</strong>troduction and use has profoundly distorted historicalcattle raid<strong>in</strong>g by escalat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>tensity of the violence and the<strong>in</strong>evitable retaliatory cycle. In Uganda unauthorised civiliangun possession is actively suppressed by military and police butguns were reported to be hidden, or be<strong>in</strong>g used for crim<strong>in</strong>alactivity. Traditional weapons such as spears, arrows, shields,clubs, and pangas are also used.1 http://genevadeclaration.org/<strong>pdf</strong>s/Geneva_Declaration_Geneva_Declaration_AVD_as_of_25.07.08.<strong>pdf</strong>2 OECD, <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Reduction: Enabl<strong>in</strong>g Development, 2009, pp 49-50.6

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>Executive SummaryWorld Vision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and development activities werereported by communities visited to have assuaged the levelor <strong>in</strong>tensity of violence <strong>in</strong> each area, but not elim<strong>in</strong>ated it.One of the more <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs came <strong>in</strong> Kenya wherethe research team visited three pastoralist communities, theTurkana, Pokot and Marakwet. While the Turkana and Pokotcont<strong>in</strong>ue <strong>in</strong> a deadly cycle of retaliatory cattle raid<strong>in</strong>g violencewith only some abatement, the Marakwet have fashioned afunctional peace with their former opponents, the Pokot. Why?A comb<strong>in</strong>ation of <strong>in</strong>creased diversity <strong>in</strong> livelihoods, changes<strong>in</strong> cultural patterns related to marriage and dowry, socialcontrol of gun possession and use, and active peace-mak<strong>in</strong>g bythe Marakwet supported by World Vision and other NGOs,provide part of the answer. This may offer clues about how awider peace can be secured among pastoralists <strong>in</strong> Kenya and<strong>in</strong> the broader cross-border region referred to as the Karamojacluster.In Sudan the post-conflict violence between cattle-raid<strong>in</strong>gpastoralist communities <strong>in</strong> Warrap State has been addressed<strong>in</strong> some places through local peace negotiations, but violencereturned. To be susta<strong>in</strong>able, peace agreements likely willrequire re<strong>in</strong>forcement through substantial <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong>economic development and <strong>in</strong>frastructure as well as <strong>in</strong>creasedformal security and civilian disarmament that is sanctioned bythe communities themselves.In Northern Uganda, the ostensible end of the <strong>in</strong>surgency bythe Lord’s Resistance Army <strong>in</strong> 2006 left people grappl<strong>in</strong>g withdifferent forms of post-conflict violence. Local peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gefforts were reported to be effective <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g these typesof localised violence, but people’s cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g fear of the LRA’sreturn led them to acknowledge that national and <strong>in</strong>ternational<strong>in</strong>terventions would be required to address any resumption ofthe <strong>in</strong>surgency.to attack from their rivals who had not been disarmed. Oneperson <strong>in</strong>terviewed stated the problem this way: “In the faceof <strong>in</strong>security, people reta<strong>in</strong> weapons.” A range of issues mustbe addressed alongside disarmament for it to be effective,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: enhanced state-sponsored security through thepolice, military, or properly regulated volunteer protectionforces; changes to cultural and livelihood patterns; <strong>in</strong>creasedbasic <strong>in</strong>frastructure and services (roads, schools, cl<strong>in</strong>ics,etc.); and, most importantly, a determ<strong>in</strong>ation by thoseperpetrat<strong>in</strong>g violence to stop.Those people <strong>in</strong>terviewed confirmed that many of the<strong>in</strong>gredients <strong>in</strong> the recipe for susta<strong>in</strong>able peace come not onlyfrom peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities but also from developmentprogramm<strong>in</strong>g. World Vision activities <strong>in</strong> these two areaswere consistently cited by those <strong>in</strong>terviewed as contribut<strong>in</strong>gto peace or reduc<strong>in</strong>g the frequency and <strong>in</strong>tensity of armedviolence. One respondent made the connection this way:“Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g is not mean<strong>in</strong>gful on an empty stomach.” Atthe same time, calls were consistently heard for greater WorldVision support to education, livelihoods, health care, potablewater, better roads and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for peace committees,among other <strong>in</strong>terventions. These calls did not articulate afirm dist<strong>in</strong>ction between peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and developmentactivities.Additionally, people consistently spoke positively about thecontribution of specific peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and sensitisation to alternatives to violence. Therewere frequent references to World Vision’s collaborativeapproach with others, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g local government officials,NGOs and community based organisations, and securityservices. World Vision also has worked successfully withlocal communities and NGO colleagues <strong>in</strong> advocat<strong>in</strong>g for<strong>in</strong>creased government services and protection.Forcibly remov<strong>in</strong>g guns <strong>in</strong> Warrap State <strong>in</strong> Southern Sudancommunities <strong>in</strong> and of itself was reported to be an <strong>in</strong>effectivesolution to armed violence. Disarmament reportedly<strong>in</strong>creased the frequency and <strong>in</strong>tensity of armed violencewhere unequal weapons removal among rival groups leftdisarmed communities without security and more vulnerable<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision Canada trust thatthis report will contribute to the grow<strong>in</strong>g body of evidencebasedresearch call<strong>in</strong>g for government, civil society anddonor partners <strong>in</strong> development to understand that address<strong>in</strong>garmed violence is <strong>in</strong>tegral to successful development andpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g programm<strong>in</strong>g.7

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>1. IntroductionThis cooperative study between a disarmament organisation,<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, and an <strong>in</strong>ternational Christian relief,development and advocacy organisation, World Vision(WV), was undertaken to document if and how World Visionpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and development <strong>in</strong>itiatives are contribut<strong>in</strong>g toreductions <strong>in</strong> armed violence. It also records the assessment ofthe impact of World Vision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities by people<strong>in</strong> violence-affected communities. The research was undertaken<strong>in</strong> selected areas of Kenya, Uganda and Sudan over a threeweekperiod <strong>in</strong> September 2008.Because it is widely recognised that assistance delivered withoutsensitivity to conflict dynamics can make the conflict worse,development practitioners, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g World Vision, have long<strong>in</strong>tegrated “Do No Harm” (DNH) strategies associated withMary B. Anderson <strong>in</strong>to relief or development programmes<strong>in</strong> areas affected by armed violence. Development and reliefresources represent a transfer of wealth, and therefore power,<strong>in</strong>to a community. If underly<strong>in</strong>g tensions or conflicts <strong>in</strong> thecommunity are not accounted for, external assistance canfavour one group over another, mak<strong>in</strong>g tensions worse. DNHstrategies would generally be expected <strong>in</strong> good developmentand relief programm<strong>in</strong>g.It is also clear that development <strong>in</strong>vestments can be wasted ifguns are be<strong>in</strong>g used to kill and <strong>in</strong>jure people, if <strong>in</strong>frastructureis be<strong>in</strong>g destroyed, if agricultural activity is be<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>in</strong>dered,if access to markets is <strong>in</strong>terrupted, or if people are <strong>in</strong> a stateof debilitat<strong>in</strong>g fear or are <strong>in</strong> flight from armed violence.Respond<strong>in</strong>g to gun violence, however, is not necessarily viewedas an important part of sound development programm<strong>in</strong>g – atleast not yet.<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> armed violence through disarmament processesthat focus on <strong>in</strong>terrupt<strong>in</strong>g the supply of guns or remov<strong>in</strong>g themfrom post-conflict situations or from areas of armed crim<strong>in</strong>alviolence also has proven extremely difficult <strong>in</strong> practice. Indeed,<strong>in</strong> some cases disarmament has actually <strong>in</strong>creased the frequencyand <strong>in</strong>tensity of armed violence – for example, when there hasbeen an imbalance <strong>in</strong> weapons removal among rival groups.To date, development <strong>in</strong>terventions and disarmamentefforts have not rout<strong>in</strong>ely been l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>abledevelopment and susta<strong>in</strong>able peace <strong>in</strong> response to situations ofarmed conflict.NIGEL MARSH / World VisionA child <strong>in</strong> a displaced persons’ camp <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong>ern Uganda. Throughoutthe research, people reported be<strong>in</strong>g displaced due to armed violence.Countries <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>, which <strong>in</strong>clude Kenya, Uganda andSudan – the subjects of this research – consistently rank nearthe bottom of the United Nations Development Programme’sHuman Development Index. 1 They have been particularlyhard-hit by the pervasive presence of small arms and lightweapons. Part of the solution <strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>able peace isthe control and removal of guns. Unfortunately, there are noeasy methods to control the supply of weapons to and betweenthese countries, which have suffered for decades from civil wars,<strong>in</strong>surgencies and wars between states. Multilateral agreementsto restrict the supply of weapons and to support disarmamentprograms are slowly be<strong>in</strong>g implemented but to date they havehad limited impact. 21 The HDI of the UNDP ranked 179 countries <strong>in</strong> 2008 based on 2006 statistics.The respective rank<strong>in</strong>gs for Kenya, Sudan and Uganda were 144, 146 and 156.See http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2007-2008/2 The three states are politically bound by commitments under the UnitedNations Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade<strong>in</strong> Small Arms and Light Weapons <strong>in</strong> All Its Aspects (PoA), agreed <strong>in</strong> 2001. Theyalso are signatories to the legally b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention,Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons <strong>in</strong> the Great LakesRegion and the Horn of <strong>Africa</strong>, which entered <strong>in</strong>to force <strong>in</strong> 2006. Under theterms of the Nairobi Protocol the three states have established national focalpo<strong>in</strong>ts to coord<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong>formation-shar<strong>in</strong>g on Protocol implementation and, <strong>in</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g with the PoA, Kenya and Uganda have produced National Action Planson Small Arms and Light Weapons. In addition, Kenya, Uganda and Sudanhave endorsed the Geneva Declaration on <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> and Development(GD). Kenya is one of the orig<strong>in</strong>al 42 signatories and is a member of the “CoreGroup” promot<strong>in</strong>g the GD. Kenya is also one of five states subject to a “nationalassessment” by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), theUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), theUnited Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World HealthOrganization (WHO). The assessment will compile “systematic <strong>in</strong>ventories ofarmed violence reduction at the country level” and conduct pilot projects (TheGeneva Declaration Secretariat, <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Prevention and Reduction: AChallenge for Achiev<strong>in</strong>g the Millennium Development Goals, 2008, p 16, http://www.genevadeclaration.org/<strong>pdf</strong>s/GD%20Background%20Paper.<strong>pdf</strong> ).8

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>1. IntroductionThe challenge of constructively l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g,development and armed violence reduction crosses traditionaldiscipl<strong>in</strong>es and World Vision and <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> br<strong>in</strong>gdifferent but complementary experience to this study.Founded <strong>in</strong> 1950, World Vision has world-wide experienceimplement<strong>in</strong>g programmes <strong>in</strong> emergency relief, communitydevelopment and the promotion of justice <strong>in</strong> almost 100countries. World Vision def<strong>in</strong>es peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g as “programmesand activities that address the causes of conflict and thegrievances of the past, that promote long-term stability andjustice, and that have peace-enhanc<strong>in</strong>g outcomes. Susta<strong>in</strong>edprocesses of peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g steadily rebuild or restore networksof <strong>in</strong>terpersonal relationships, contribute toward just systemsand cont<strong>in</strong>ually work with the <strong>in</strong>teraction of truth and mercy,justice and peace.” 3Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g is pr<strong>in</strong>cipally a cross-cutt<strong>in</strong>g theme <strong>in</strong> its work<strong>in</strong> conflict-affected areas. World Vision uses three differentconflict analysis tools to identify conflict-sensitive practicesat different levels of engagement. At the macro level, WV’scustom-designed Mak<strong>in</strong>g Sense of Turbulent Contexts (MSTC)workshop facilitates an analysis of the political, social andeconomic dynamics that fuel <strong>in</strong>stability <strong>in</strong> a country. MSTCworkshop participants – drawn from civil society, government,and multilateral organisations – determ<strong>in</strong>e appropriateprogrammatic and policy responses to the turbulence. At thedevelopment programme level, the Integrat<strong>in</strong>g Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gand Development (IPAD) framework gives communitiesand their partners (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g WV) tools to promote goodgovernance, transformed <strong>in</strong>dividuals, coalition-build<strong>in</strong>g,community capacities for peace, and susta<strong>in</strong>able and justlivelihoods. F<strong>in</strong>ally, at the grassroots level, World Vision appliesthe Do No Harm/Local Capacities for Peace (DNH/LCP)framework, orig<strong>in</strong>ally developed by Mary B. Anderson and theCollaborative for Development Action. DNH/LCP exam<strong>in</strong>esthe impact of humanitarian and development assistance onconflict and promotes the development of local capacitiesfor peace. In addition, World Vision empowers children andyouth around the world to be peacemakers, and develops anddistributes peace education materials and curricula. Throughapplication of these frameworks, World Vision has ga<strong>in</strong>edexperience <strong>in</strong> foster<strong>in</strong>g community-level efforts to build peace<strong>in</strong> conflict-affected zones.3 From WVI Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Operational Def<strong>in</strong>itions, November 2001, as cited<strong>in</strong> AmaNet Strategy 2007-2009.9JON WARREN / World Vision

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>1. Introduction<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>, a Canadian-based NGO founded <strong>in</strong>1976, carries out research and develops policy on disarmamentprocesses, particularly measures to control and reduce theproliferation and misuse of small arms and light weapons.<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> participates <strong>in</strong> a grow<strong>in</strong>g network ofNGOs that are explor<strong>in</strong>g the policy and practice of armedviolence reduction <strong>in</strong> development programm<strong>in</strong>g. This researchbuilds on the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and recommendations of a 2007<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> report for the Canadian InternationalDevelopment Agency, Towards Safe and Susta<strong>in</strong>ableCommunities: <strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> as a DevelopmentPriority. 4The tools and frameworks used by World Vision to <strong>in</strong>tegratepeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g with relief and development activities arean important backdrop to this study, but no attempt hasbeen made to evaluate the tools, the frameworks or thepeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities themselves. Instead, observations areprovided <strong>in</strong> the conclud<strong>in</strong>g section of this study on the arrayof developmental and disarmament processes necessary toaccomplish the goals of each where armed violence is imped<strong>in</strong>gpoverty alleviation.This study fits with<strong>in</strong> a wider discussion tak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong> policycircles and among development donors that l<strong>in</strong>ks armedviolence reduction and development processes. In the <strong>East</strong><strong>Africa</strong> region this l<strong>in</strong>kage has been described as “an emerg<strong>in</strong>g– and more <strong>in</strong>tegrated – set of policies premised on <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gcommunity security and development <strong>in</strong> order to promotevoluntary weapons collection.” 5 Globally, the discussionhas been encapsulated <strong>in</strong> the Geneva Declaration on <strong>Armed</strong><strong>Violence</strong> and Development, <strong>in</strong>itiated by the Government ofSwitzerland and now signed by over 100 countries.The Geneva Declaration (GD) recognises that securityfrom armed violence and the threat of armed violence isa basic human need to which the poor, the marg<strong>in</strong>alised,women and children are entitled, and a pre-requisite forsusta<strong>in</strong>ed economic development. 6 <strong>Armed</strong> violence is widelyacknowledged to be a major obstacle to achiev<strong>in</strong>g theMillennium Development Goals and the Geneva Declaration4 http://www.ploughshares.ca/libraries/Work<strong>in</strong>gPapers/wp072.<strong>pdf</strong>5 J Bevan, Crisis <strong>in</strong> Karamoja: <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> and the Failure ofDisarmament <strong>in</strong> Uganda’s Most Deprived Region, Small Arms Survey,Geneva, 2008, p 17, http://www.reliefweb.<strong>in</strong>t/rw/RWFiles2008.nsf/FilesByRWDocUnidFilename/ASIN-7GJSQY-full_report.<strong>pdf</strong>/$File/full_report.<strong>pdf</strong>6 See http://www.genevadeclaration.orgpledges of signatory states to obta<strong>in</strong> measurable reductions <strong>in</strong>armed violence by 2015. Led by a core group of states, the GDprocess is adopt<strong>in</strong>g a three-track approach by encourag<strong>in</strong>gthe development of concrete measures concern<strong>in</strong>g advocacy,dissem<strong>in</strong>ation and coord<strong>in</strong>ation; mapp<strong>in</strong>g and monitor<strong>in</strong>g; andpractical programm<strong>in</strong>g.It is hoped that this report will add to the practicalprogramm<strong>in</strong>g track of the GD process. The researchers also<strong>in</strong>tend that the report will contribute to the grow<strong>in</strong>g body ofliterature that <strong>in</strong>forms, from actual practice <strong>in</strong> the field, the“emerg<strong>in</strong>g policy frameworks” on comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g armed violencereduction <strong>in</strong>itiatives with development programmes. It also maydemonstrate <strong>in</strong> a practical manner how peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g workswith<strong>in</strong> World Vision programm<strong>in</strong>g, thereby strengthen<strong>in</strong>gsupport for peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities with<strong>in</strong> World Vision itself,and possibly with<strong>in</strong> the wider NGO development community.Care has been taken <strong>in</strong> record<strong>in</strong>g and report<strong>in</strong>g what peoplesaid <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews and focus groups. Contradict<strong>in</strong>g facts and<strong>in</strong>terpretations of the context for violence and specific <strong>in</strong>cidentsof violence are deliberately preserved as they were presented<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews. In situations of armed violence it is commonthat the narratives of oppos<strong>in</strong>g sides differ. Because enemiesdo not share an understand<strong>in</strong>g of what has happened, whostarted what, and why, negotiat<strong>in</strong>g peace agreements and thenma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g peace are difficult to achieve. In the end, whileoppos<strong>in</strong>g sides do not need to agree with each other on all theanswers to these questions, know<strong>in</strong>g how enemies answer thesequestions forms one base on which peace can be built.As the report was consolidated it became <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clearto the researchers that those <strong>in</strong>terviewed already knew,collectively, the many elements of the broader solution requiredto stop the violence <strong>in</strong> their communities. These women, men,youth, government officials, traditional leaders, World Visionand other NGO staff, police and security officials did notrequire helpful h<strong>in</strong>ts from the researchers about what is neededto end violence.F<strong>in</strong>ally, World Vision staff made a commitment to report backto the communities who participated <strong>in</strong> this research. Oneof the most ambitious potential roles for this research report,admittedly an imperfect mirror, is that, <strong>in</strong> say<strong>in</strong>g back toparticipants what they said <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews, it might assist <strong>in</strong> thepeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g processes already begun <strong>in</strong> their communities.10

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>2. Research MethodologyThis study is the result of community-level key <strong>in</strong>formant<strong>in</strong>terviews and focus groups held <strong>in</strong> Kenya, Uganda and Sudan,undertaken <strong>in</strong> September 2008. World Vision programme andproject documentation and selected secondary sources werealso reviewed.Figure 2.1: The <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Lens of OECD-DAC 2Both formal <strong>in</strong>stitutions ofgovernance and <strong>in</strong>formal(traditional and cultural) norms,rules and practicesThe primary objective of the research was to study WorldVision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g projects that were undertaken <strong>in</strong> thecontext of development and humanitarian relief operationsand to document their impact on levels of armed violence. Thiswas not a formal, external evaluation or assessment exercise.All aspects of the study were designed cooperatively between<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong> and World Vision staff, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gdevelopment and modification of the questionnaires used <strong>in</strong> thefield research, and the conduct of the field research itself. Someprovisional observations are provided but there is no attempt toformulate specific recommendations for future World Visionprogramm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> these countries or elsewhere.The questionnaires (see Appendix 1) drew on the experienceand language of earlier related research conducted <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong><strong>Africa</strong> by World Vision and other development NGOs. Thequestionnaires were also <strong>in</strong>fluenced by the “armed violencelens” usefully proposed by The SecDev Group and the SmallArms Survey <strong>in</strong> their guidance for the Development AssistanceCommittee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operationand Development (OECD-DAC). This armed violence lenshas become an analytical tool of the OECD-DAC to assist thepromotion of effective and practical measures to prevent andreduce armed violence. It emphasises four key elements:• the people or populations that are affected by armedviolence;• the perpetrators of armed violence (and their motives);• the <strong>in</strong>struments of armed violence;• and the wider <strong>in</strong>stitutional or cultural environment thatenables (or protects aga<strong>in</strong>st) violence. 1GlobalRegionalNationalLocalInstrumentsIncludes the unregulatedavailability and distribution ofSALW, m<strong>in</strong>es, explosiveremnants of war (ERW), andfactors affect<strong>in</strong>g their supplyInstitutionsPeopleIndividuals, communitiesand societies affected byarmed violenceAgentsPerpetrators of armedviolence and motivationsfor acquisition and misuseof arms(demand factors)The armed violence lens deliberately “chooses a people-centredperspective on security.” 3 This “bottom-up” approach is crucialto formulat<strong>in</strong>g what is needed to make threatened <strong>in</strong>dividualsand communities feel safe and secure. It is <strong>in</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g withpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g frameworks and practices of World Vision,which engage programme partners at the community level anduse tools such as the “Local Capacities for Peace” <strong>in</strong>itiatives.Indeed, the lens is <strong>in</strong>tended to be a complementary tool. 4The questionnaires used <strong>in</strong> this research focused on gather<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> three ma<strong>in</strong> areas:• An assessment of the security situation <strong>in</strong> the communitiesvisited;• The <strong>in</strong>struments used <strong>in</strong> armed violence; and• World Vision peace projects and their impact on armedviolence.Special attention was given to the roles of women and men,youth and children, as victims of violence and as perpetrators.1 OECD, <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> Reduction: Enabl<strong>in</strong>g Development, 2009, pp 49–50.See also pp 51–58. www.oecd.org/dac/<strong>in</strong>caf2 Ibid., p 50.3 Ibid., p 51.4 “It is important to note that the armed violence lens should not supplantexist<strong>in</strong>g assessment and programm<strong>in</strong>g tools such as conflict or stabilityassessments; drivers of change, governance and crim<strong>in</strong>al justice assessments;or a public health approach. Rather, it serves as a complementary frameworkthat can help to identify how different tools and data sources can be comb<strong>in</strong>edto enhance exist<strong>in</strong>g diagnostics and formulate more strategic or targeted<strong>in</strong>terventions” (ibid., p 51).11

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>2. Research MethodologyThe impact of the peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g projects cannot be understoodwithout some explanation of the context <strong>in</strong> which the violenceis tak<strong>in</strong>g place. No attempt is made <strong>in</strong> this report, however, toprovide a comprehensive description of the history or currentdynamics of the violent conflicts <strong>in</strong> which these communitiesare engulfed or the type, number and economics of theweapons used. The complexities and nuances of the armedconflicts of the region require more extensive research andanalysis than was available to this study; researchers spent onlyone week <strong>in</strong> each country.In consultation with WV field-level colleagues, the researchteam chose a three-year timeframe for pos<strong>in</strong>g questions aboutwhether the violence was <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g or decreas<strong>in</strong>g. This periodcould have been longer or shorter, but it was fixed for questions<strong>in</strong> all three countries to assist <strong>in</strong> compar<strong>in</strong>g the content ofanswers.The <strong>in</strong>terview and focus group responses are the primarysource used to summarise and synthesise a description of thecontext for violence and the <strong>in</strong>struments of violence used. Anumber of secondary resources are also referenced.Figure 2.2 categorises the people <strong>in</strong>terviewed accord<strong>in</strong>g to age,gender and country.Figure 2.2: Summary of field research participantsCountryMaleadultsMaleyouthFemaleadultsFemaleyouthKenya 37 29 11Uganda 44 17 35 15Sudan 23 32 38 3Total 104 49 102 29In consultation with WV staff <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>, the researchersagreed that youth participants should be 18 years and older,and that all research participants, youth or adult, should befamiliar with or collaborat<strong>in</strong>g directly <strong>in</strong> WV programs. Byvisit<strong>in</strong>g communities likely to express different po<strong>in</strong>ts of view– for example, Pokot, Turkana and Marakwet communities<strong>in</strong> Kenya – researchers hoped to achieve a reasonable range ofperspectives. WV field staff selected people to participate <strong>in</strong>the research, us<strong>in</strong>g a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of convenience and snowballsampl<strong>in</strong>g techniques. Categories of people <strong>in</strong>terviewed<strong>in</strong>cluded WV staff <strong>in</strong> the host countries, local governmentofficials, security sector officials (police and military),traditional community leaders/chiefs/elders, staff of local or<strong>in</strong>ternational NGOs, religious leaders, and youth and adultsfrom the communities. In communities affected by cattlerustl<strong>in</strong>g, the last group <strong>in</strong>cluded some <strong>in</strong>dividuals identified as“warriors” or “raiders”.Data was collected by teams compris<strong>in</strong>g WV staff membersfrom the host country (staff work<strong>in</strong>g directly at the projectlevel and/or staff from the national WV headquarters), localtranslators (where necessary), and a WV Canada or <strong>Project</strong><strong>Ploughshares</strong> staff person. All notes taken from focus group,<strong>in</strong>formant and other <strong>in</strong>terviews were compiled and analysedby <strong>Project</strong> <strong>Ploughshares</strong>. The OECD-DAC armed violence lens(AVL) was used to structure the sections on each <strong>in</strong>dividualcountry and the research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are organised accord<strong>in</strong>g tothe four AVL categories.Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter and theongo<strong>in</strong>g violence <strong>in</strong> the communities visited, participantswere <strong>in</strong>formed that they would not be identified <strong>in</strong> the report,and that their names would rema<strong>in</strong> confidential. They were<strong>in</strong>formed about the purpose of the research, its potentialbenefits and what will be done with the results. They were alsoassured that they were free not to participate, and to decl<strong>in</strong>eto answer any question. Efforts were made to hold <strong>in</strong>terviewsand focus groups <strong>in</strong> safe places where participants could feelcomfortable to speak openly. Attention was also paid to genderrelatedsensitivities <strong>in</strong> the subject matter by, for example,hold<strong>in</strong>g several “women only” or “women youth only” focusgroups, led by an all-female research team. The exact researchlocations have also not been <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> this report to furtherprotect the identity of participants. In addition, the photos <strong>in</strong>this report do not show people who participated <strong>in</strong> the researchand do not depict exact research locations. Instead, the photoswere selected from World Vision’s collection to depict widerregions under study <strong>in</strong> the research (Kenya’s North Rift Valley,Northern and <strong>East</strong>ern Uganda, and Southern Sudan).Most of the community-level <strong>in</strong>terviews were facilitated bytranslation from local languages <strong>in</strong>to English. Notes were keptof the English translations, sometimes with more than one12

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>2. Research Methodology<strong>in</strong>terviewer keep<strong>in</strong>g notes to allow for later comparisons. Thereported comments <strong>in</strong> the text of the report are the Englishtranslations of the orig<strong>in</strong>al answers to <strong>in</strong>terview questions.They have been rendered as faithfully as possible under thecircumstances, but should only be used with the understand<strong>in</strong>gthat nuances of mean<strong>in</strong>g and perhaps facts have been lost <strong>in</strong> thetranslation and render<strong>in</strong>g of quotations.F<strong>in</strong>ally, it should be stressed that much of the “hard” or“factual” <strong>in</strong>formation given <strong>in</strong> community-level <strong>in</strong>terviewscould not be <strong>in</strong>dependently verified by the research team. Thisis a significant caveat to the research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. The <strong>in</strong>formationrecorded <strong>in</strong>dicates the knowledge and perceptions of the people<strong>in</strong> these violent conflict situations.13SETH LE LEU / World Vision

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>3. KenyaDue to the sensitive nature of this research, the photos <strong>in</strong> this chapter do not show people who participated <strong>in</strong> the research and do not depict exact research locations. Instead,the photos were selected from World Vision’s collection to show different scenes from life <strong>in</strong> Kenya’s North Rift Valley and World Vision’s work with communities there.14JON WARREN / World Vision

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>3. Kenya3.1. Apply<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>Lens to KenyaThe OECD-DAC armed violence lens will be used to analysethe results of <strong>in</strong>terviews conducted <strong>in</strong> the North Rift Valley ofKenya. Captur<strong>in</strong>g the security perceptions of armed-violenceaffectedpopulations was a key objective of the questionnairesused for <strong>in</strong>terviews with people engaged with World Visionpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g programmes <strong>in</strong> Kenya. The <strong>in</strong>troductory partof the questionnaire was <strong>in</strong>tended to provide a people-centredsecurity assessment. We beg<strong>in</strong> by summariz<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>dividualand community perceptions of security revealed by the<strong>in</strong>terviews. An arbitrary three-year timeframe was used <strong>in</strong> thequestions to determ<strong>in</strong>e people’s perceptions of whether violencewas <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g or decreas<strong>in</strong>g over time.Affected PopulationsThe North Rift Valley area <strong>in</strong> northwest Kenya is one offive World Vision Kenya (WVK) operational zones. TheWVK work <strong>in</strong> the North Rift Zone deals with four districts– Turkana, West Pokot, Marakwet and Bar<strong>in</strong>go (<strong>East</strong> Pokot) –and three pastoralist communities – the Marakwet, Pokot andTurkana. There are other m<strong>in</strong>ority groups <strong>in</strong> these areas.The predom<strong>in</strong>ant threat to peace <strong>in</strong> the pastoralist communities<strong>in</strong> the North Rift Valley is the armed violence associated withcattle raids. Steal<strong>in</strong>g cattle was traditionally done by youngmen to secure a bride price or dowry. Steal<strong>in</strong>g livestock andkill<strong>in</strong>g someone from another community <strong>in</strong> a raid garneredfame <strong>in</strong> these cultures. Dances and songs celebrated the deathsof those killed dur<strong>in</strong>g raids or fights. But the <strong>in</strong>troduction ofautomatic weapons, primarily AK-47s, irrevocably changedthe dynamic of cattle raids as the number of people killed and<strong>in</strong>jured dramatically <strong>in</strong>creased dur<strong>in</strong>g raids and retaliatoryactions. Gun–related violence cuts across all districts <strong>in</strong> theNorth Rift Valley area, heightened by cross-border gun violenceand gun trade between Kenya and Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopiaand Somalia.One person <strong>in</strong>terviewed provided a brief history of the<strong>in</strong>troduction of guns <strong>in</strong> the area:Thirty or 40 years ago the Turkana and Pokot raided eachother us<strong>in</strong>g spears and arrows. It was part of traditionalpractices, and sometimes a “friendly” activity. The firstguns were <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> 1968. These were simple weaponswithout much power that could be purchased for 100cows. If you had a gun you could raid many communities.The pressure was there for everyone to obta<strong>in</strong> guns, andcattle raids became rampant. Guns flooded <strong>in</strong>to the area.Raid<strong>in</strong>g for cattle shifted to hunt<strong>in</strong>g humans and then tooutright banditry.Community-level <strong>in</strong>terviews and focus groups were undertakenat specific sites where the Turkana, Pokot and Marakwet live.<strong>Violence</strong> between the Turkana and Pokot cont<strong>in</strong>ues, withsubstantial numbers of deaths and <strong>in</strong>juries related to cattleraids, although <strong>in</strong> the last three years the number of raidsand the number of people killed and <strong>in</strong>jured <strong>in</strong> those raidswere generally reported as decreas<strong>in</strong>g. Between the Pokot andMarakwet, however, there is a functional and relatively stablePastoralists pass a motorcycle <strong>in</strong> the North Rift Valley region.15JON WARREN / World Vision

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>3. Kenyapeace. The reasons given for this peace, and for fewer guns andless gun use among the Marakwet, are among the importantf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the field research <strong>in</strong> Kenya and are described morefully at the end of this chapter. Deliberate cultural changeswere <strong>in</strong>stituted, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g decreas<strong>in</strong>g the practice of dowry orbride price; <strong>in</strong>creased reliance on agriculture, thereby lessen<strong>in</strong>gdependence on livestock herd<strong>in</strong>g; and greater social control ofgun possession and use.But the <strong>in</strong>troduction of automaticweapons, primarily AK-47s, irrevocablychanged the dynamic of cattle raids.The people <strong>in</strong>terviewed reported that illiteracy, poverty andisolation had an impact on the level of violence. Illiteracy isas high as 97% <strong>in</strong> some North Rift Valley areas accord<strong>in</strong>g toone WVK staff person. People are isolated <strong>in</strong> cattle camps,or kraals, and have not been exposed to alternative ways ofsettl<strong>in</strong>g conflicts or different livelihood possibilities. Tribalgroups compete with each other over boundaries and toexpand their political power. Idleness among young men, aged15–30, also contributes to the frequency and <strong>in</strong>tensity of raids.Paradoxically, we heard that opponents will come together <strong>in</strong>times of drought to share water and pasture, but then fightaga<strong>in</strong> when there is plenty.One person <strong>in</strong>terviewed said that 18 of his family membershad been killed <strong>in</strong> the past three years, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g his fatherand mother. Another said that 10 relatives had been killed,but not his wife or children. One person claimed not to havebeen personally affected by violence, but said that a sister hadhad her house robbed and another had been forced to flee.One focus group member described los<strong>in</strong>g four cous<strong>in</strong>s to theviolence.One community member summed up his frustration over thefutility of cattle raid<strong>in</strong>g this way: “Go on enough raids youwill eventually die. Cows are simply circulat<strong>in</strong>g between thecommunities.”Pastoralists are not the only ones who come under attackdur<strong>in</strong>g raids. Government officials and security personnelhave also been killed and <strong>in</strong>jured. A District Commissioner(DC) was reported by another government official to havebeen nearly killed <strong>in</strong> early March 2008. The DC escaped withm<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>juries from a shattered w<strong>in</strong>dscreen. The <strong>in</strong>terviewee<strong>in</strong> question did not believe that the attackers knew they wereattack<strong>in</strong>g the DC, s<strong>in</strong>ce they were robb<strong>in</strong>g another vehicle whenthe DC arrived.A government official described the stress he feels liv<strong>in</strong>g andwork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the area. When he worked at the Pokot–Marakwetborder there were clashes and raids from 1997 to 2003. His firsthouse was on the border; and “when there is a crisis, you arecollateral damage. It was very stressful.”Other types of armed violence were described, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g postelectionviolence follow<strong>in</strong>g national elections <strong>in</strong> December2007, land disputes between pastoralist groups, road banditry,sexual assault and rape, and common banditry or crim<strong>in</strong>al acts.Post-election violence <strong>in</strong> Kenya, which was particularly <strong>in</strong>tense<strong>in</strong> Eldoret, was mentioned <strong>in</strong> pass<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>terviews but didnot emerge as a prom<strong>in</strong>ent theme <strong>in</strong> this research.<strong>Violence</strong> between the Turkana and PokotThe people <strong>in</strong>terviewed had different ideas about the frequencyof violent <strong>in</strong>cidents between the Turkana and Pokot. One personsaid that, three years ago, <strong>in</strong>cidents took place 20 to 50 timesa month; now maybe there is one <strong>in</strong>cident per month or every2 months. Another person said that about 100 Turkana werekilled <strong>in</strong> 2008, with almost 40 <strong>in</strong> August alone.The general reduction reported <strong>in</strong> the number of violent cattleraids between Turkana and Pokot was sometimes qualifiedaccord<strong>in</strong>g to specific areas with<strong>in</strong> the broader territory. Forexample, the downward trend <strong>in</strong> cattle raids was true for centralPokot, but not for north and east Pokot where small-scale raidsare ongo<strong>in</strong>g, accord<strong>in</strong>g to a government official <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>terview.Functional Peace between the Pokot andMarakwetThe general trend of stable peace between the Pokot andMarakwet was recounted, with reasons why the peace ishold<strong>in</strong>g. Some of the explanations <strong>in</strong>cluded:The Marakwet and Pokot <strong>in</strong>teract together <strong>in</strong> markets.There aren’t attacks by the Pokot because the elders of thePokot and Marakwet resolved to live <strong>in</strong> peace together.16

<strong>Address<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Armed</strong> <strong>Violence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>3. KenyaBox 3.1.1. CEWARN–IGADEarly Warn<strong>in</strong>g DataIt is difficult to f<strong>in</strong>d reliable sources of <strong>in</strong>formation and data onthe impact of armed violence between pastoralists <strong>in</strong> Kenya andthose <strong>in</strong> neighbour<strong>in</strong>g countries. The Conflict Early Warn<strong>in</strong>gand Response (CEWARN) mechanism of the Horn of <strong>Africa</strong>sub-regional political organisation, the IntergovernmentalAuthority on Development (IGAD), has been track<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cidentsrelated to pastoral conflicts on the Kenyan side of the Karamojacluster from six report<strong>in</strong>g locations s<strong>in</strong>ce January 2004. As<strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> CEWARN’s title, the primary purpose of thedata collection is to provide early warn<strong>in</strong>g of troubles so thatappropriate state authorities and others can take action to stop<strong>in</strong>cidents. The data is collected by national research <strong>in</strong>stitutesand forwarded on a quarterly basis to the CEWARN office <strong>in</strong>Addis Ababa where the consolidated reports are posted on theCEWARN website (http://www.cewarn.org/<strong>in</strong>dex.htm).The number of human deaths reported for the Kenyan sideof the Karamoja Cluster for the period January 2004 toAugust 2008 is 566, of which 50 were reported to be womenand children. If these cumulative totals are accurate andcomprehensive, they <strong>in</strong>dicate that almost 92% of those killed <strong>in</strong>the violence are men. It may be possible to drill down <strong>in</strong>to theprimary data to get more localised results that could be relatedto the specific sites where World Vision or other NGOs areengag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> peace <strong>in</strong>itiatives.Each year s<strong>in</strong>ce 2004, the CEWARN statistics have shown aspike <strong>in</strong> the reported number of <strong>in</strong>cidents of deaths and cattlelosses <strong>in</strong> the January–April period, which roughly correspondsto the dry season <strong>in</strong> the North Rift Valley. This would suggestthat <strong>in</strong>creased movement of cattle to f<strong>in</strong>d scarce water andpasture can be a primary trigger for violent <strong>in</strong>cidents. In theJanuary–April 2008 report the conclusion is drawn that, “<strong>in</strong>terms of early warn<strong>in</strong>g and early response, it therefore meansmore preventative <strong>in</strong>terventions must be stepped up at thebeg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of a new year”. The CEWARN report<strong>in</strong>g also covers<strong>in</strong>dicators of peace <strong>in</strong>itiatives and mitigat<strong>in</strong>g behaviours. WorldVision peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g activities are mentioned <strong>in</strong> the narrativeof the May–August 2008 report: “the unh<strong>in</strong>dered distributionof relief food and cont<strong>in</strong>ued access to education and health careservices <strong>in</strong> most of the areas of report<strong>in</strong>g also served to mitigateconflict. Several civil society organizations such as Oxfam,Action Aid, NCCK, World Vision, and the Catholic Justiceand Peace Commission worked together with the district peacecommittees to promote peaceful coexistence throughout thecluster. This helped calm down the tensions that existed.” 11 Conflict Early Warn<strong>in</strong>g & Response Mechanism (CEWARN), Kenya–Karamoja Cluster Update, May – August 2008, p 13,http://www.cewarn.org/gendoc/clustrupdt.htmThe reported reduction <strong>in</strong> the number of large-scale violentcattle raids between Marakwet and Pokot, which could <strong>in</strong>volveup to 1,000 raiders, accord<strong>in</strong>g to one person <strong>in</strong>terviewed,does not mean that gun violence has stopped. Insecurity <strong>in</strong>Marakwet areas was related to theft and highway robbery.These crim<strong>in</strong>als aren’t necessarily Pokot, but could be localsfrom the Marakwet.Over the past two years the trend is for small robberiesof animals rather than large organised raids.”Today, the problems of <strong>in</strong>security relate to highwayrobbers, who wait for vehicles, however, these aren’tnecessarily Pokot. They could be local [Marakwet].”Incidents of sexual violence aga<strong>in</strong>st women and female youthwere recounted <strong>in</strong> Marakwet territory but were not reportedamong Turkana and Pokot.Women and Children as Victims of <strong>Violence</strong><strong>in</strong> Turkana and PokotInterview participants particularly emphasised the relativeimpact of armed violence on specific groups with<strong>in</strong> the affectedcommunities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g women and children. Traditionally,the men directly <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> raids or <strong>in</strong> defend<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>straiders were the primary perpetrators and direct victims ofviolence. Other groups of people were left alone. Now, with the<strong>in</strong>troduction of guns, the kill<strong>in</strong>g has fundamentally changed.17