- Page 1 and 2:

Commonmental healthdisordersTHE NIC

- Page 3 and 4:

© The British Psychological Societ

- Page 5 and 6:

Contents6 FURTHER ASSESSMENT OF RIS

- Page 7 and 8:

Guideline development group members

- Page 9 and 10:

Preface1 PREFACEThis guideline has

- Page 11 and 12:

Prefacecollaborative manner using t

- Page 13 and 14:

PrefaceThe experience of people wit

- Page 15 and 16:

Common mental health disorders2.2 T

- Page 17 and 18:

Common mental health disordersto ho

- Page 19 and 20:

Common mental health disordersManua

- Page 21 and 22:

Common mental health disordershighe

- Page 23 and 24:

Common mental health disordersNegat

- Page 25 and 26:

Common mental health disorderscours

- Page 27 and 28:

Common mental health disordersover

- Page 29 and 30:

Common mental health disorders2.2.6

- Page 31 and 32:

Common mental health disordersTable

- Page 33 and 34:

Common mental health disorders1996)

- Page 35 and 36:

Common mental health disordersSumma

- Page 37 and 38:

Common mental health disordersTable

- Page 39 and 40:

Common mental health disordersappli

- Page 41 and 42:

Common mental health disorderspatie

- Page 43 and 44:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 45 and 46:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 47 and 48:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 49 and 50:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 51 and 52:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 53 and 54:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 55 and 56:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 57 and 58:

Methods used to develop this guidel

- Page 59 and 60:

Access to healthcare4. ACCESS TO HE

- Page 61 and 62:

Access to healthcareunder the Menta

- Page 63 and 64:

Access to healthcare4.2.3 Studies c

- Page 65 and 66:

Access to healthcareIndividual-leve

- Page 67 and 68:

Access to healthcareJUNG2003 review

- Page 69 and 70:

Access to healthcareSCHEPPERS2006).

- Page 71 and 72:

Access to healthcare70Table 8: Clin

- Page 73 and 74:

Access to healthcareTable 9: Study

- Page 75 and 76:

Access to healthcareCHAPMAN2004 inc

- Page 77 and 78:

Access to healthcare4.4 SERVICE DEV

- Page 79 and 80: Access to healthcareBEACH2006 [Beac

- Page 81 and 82: Access to healthcareTable 12: Summa

- Page 83 and 84: Access to healthcareAll studies wer

- Page 85 and 86: Access to healthcarepractitioners h

- Page 87 and 88: Access to healthcareIndividual-leve

- Page 89 and 90: Access to healthcarefrom such popul

- Page 91 and 92: Access to healthcarestructure and d

- Page 93 and 94: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 95 and 96: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 97 and 98: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 99 and 100: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 101 and 102: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 103 and 104: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 105 and 106: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 107 and 108: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 109 and 110: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 111 and 112: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 113 and 114: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 115 and 116: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 117 and 118: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 119 and 120: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 121 and 122: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 123 and 124: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 125 and 126: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 127 and 128: Case identification and formal asse

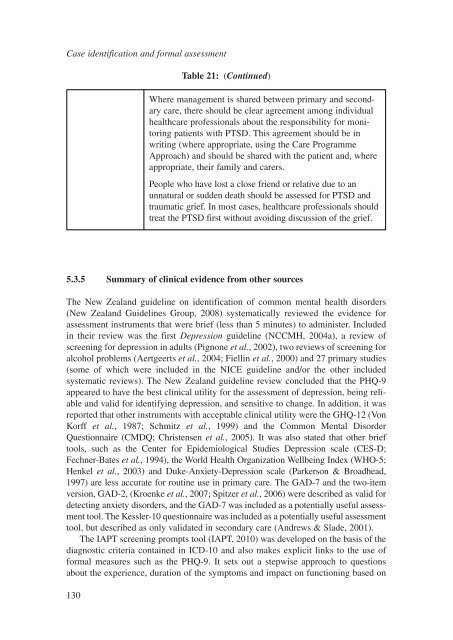

- Page 129: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 133 and 134: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 135 and 136: Case identification and formal asse

- Page 137 and 138: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 139 and 140: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 141 and 142: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 143 and 144: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 145 and 146: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 147 and 148: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 149 and 150: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 151 and 152: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 153 and 154: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 155 and 156: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 157 and 158: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 159 and 160: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 161 and 162: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 163 and 164: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 165 and 166: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 167 and 168: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 169 and 170: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 171 and 172: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 173 and 174: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 175 and 176: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 177 and 178: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 179 and 180: Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 181 and 182:

Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 183 and 184:

Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 185 and 186:

Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 187 and 188:

Further assessment of risk and need

- Page 189 and 190:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 191 and 192:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 193 and 194:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 195 and 196:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 197 and 198:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 199 and 200:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 201 and 202:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 203 and 204:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 205 and 206:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 207 and 208:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 209 and 210:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 211 and 212:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 213 and 214:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 215 and 216:

Systems for organising and developi

- Page 217 and 218:

Summary of recommendations8.1.1.6 S

- Page 219 and 220:

Summary of recommendationsFigure 12

- Page 221 and 222:

Summary of recommendations●Genera

- Page 223 and 224:

Summary of recommendations8.4 STEPS

- Page 225 and 226:

Summary of recommendations●●a g

- Page 227 and 228:

Summary of recommendationsDiscuss w

- Page 229 and 230:

Summary of recommendationsinclude p

- Page 231 and 232:

Appendices9 APPENDICESAppendix 1: S

- Page 233 and 234:

Appendix 1of a depressive disorder

- Page 235 and 236:

Appendix 1b) Assessment of anxiety

- Page 237 and 238:

Appendix 2APPENDIX 2:DECLARATIONS O

- Page 239 and 240:

Appendix 2Mr Mike BessantEmployment

- Page 241 and 242:

Appendix 2Personal non-pecuniary in

- Page 243 and 244:

Appendix 2Actions takenMr Rupert Su

- Page 245 and 246:

Appendix 2Personal family interestN

- Page 247 and 248:

Appendix 3APPENDIX 3:STAKEHOLDERS A

- Page 249 and 250:

Appendix 4ClinicalpopulationPeople

- Page 251 and 252:

Appendix 4Case identificationNo. Pr

- Page 253 and 254:

Appendix 5APPENDIX 5:REVIEW PROTOCO

- Page 255 and 256:

Appendix 7APPENDIX 7:METHODOLOGY CH

- Page 257 and 258:

Appendix 9APPENDIX 9:METHODOLOGY CH

- Page 259 and 260:

Appendix 92.10 Are all important pa

- Page 261 and 262:

Appendix 9case also excludes costs

- Page 263 and 264:

Appendix 9For consistency, the EQ-5

- Page 265 and 266:

Appendix 9Answer ‘yes’ if the a

- Page 267 and 268:

Appendix 9Answer ‘yes’ if the e

- Page 269 and 270:

Appendix 9Answer ‘yes’ if appro

- Page 271 and 272:

Appendix 10APPENDIX 10: EVIDENCE TA

- Page 273 and 274:

Appendix 11APPENDIX 11:HIGH PRIORIT

- Page 275 and 276:

Appendix 11discussion of options bu

- Page 277 and 278:

Appendix 13APPENDIX 13:GENERALIZED

- Page 279 and 280:

ReferencesAndlin-Sobocki, P., Jöns

- Page 281 and 282:

ReferencesBower, P., Gilbody, S., R

- Page 283 and 284:

ReferencesCooper, S., Smiley, E., M

- Page 285 and 286:

ReferencesEhlers A., Gene-Cos N. &

- Page 287 and 288:

ReferencesGiles, D. E., Jarrett, R.

- Page 289 and 290:

ReferencesHorowitz, M. J., Wilner,

- Page 291 and 292:

ReferencesKnapp, M. & Ilson, S. (20

- Page 293 and 294:

ReferencesMarks, J., Goldberg, D. P

- Page 295 and 296:

ReferencesNCCMH (forthcoming) Self-

- Page 297 and 298:

ReferencesOzer, E. J., Best, S. R.,

- Page 299 and 300:

ReferencesSartorius, N. (2002) Eine

- Page 301 and 302:

ReferencesTiemens, B. G., Ormel, J.

- Page 303 and 304:

ReferencesWilkinson, M. J. B. & Bar

- Page 305 and 306:

Glossarybeliefs and interpretations

- Page 307 and 308:

Glossaryto learn to become more awa

- Page 309 and 310:

Abbreviations12 ABBREVIATIONSADDADS

- Page 311 and 312:

AbbreviationsOASISOCDONSORPHQ (-A,