Biodiversity in the Estuary - Estuaries NOAA

Biodiversity in the Estuary - Estuaries NOAA

Biodiversity in the Estuary - Estuaries NOAA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Teacher Guide—Life Science ModuleActivity 3 — <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>Featured NERRS <strong>Estuary</strong>:Rookery Bay National Estuar<strong>in</strong>e ResearchReserve, Floridahttp://nerrs.noaa.gov/Reserve.aspx?ResID=RKBActivity SummaryIn this activity, students <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>credible biodiversitythat exists <strong>in</strong> estuar<strong>in</strong>e environments. They beg<strong>in</strong>by explor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay National Estuar<strong>in</strong>eResearch Reserve (NERR) us<strong>in</strong>g Google Earth. Students<strong>the</strong>n produce an estuary biodiversity concept map and<strong>in</strong>dividual organism profile that becomes part of anestuary wildlife exhibit.Learn<strong>in</strong>g ObjectivesStudents will be able to:1. Describe <strong>the</strong> physical and biological components ofhabitats that exist as part of an estuary.2. Expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> relationships between primaryproducers, consumers, and secondary consumers.3. Describe some adaptations of liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms to<strong>the</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g conditions with<strong>in</strong> an estuary.4. Expla<strong>in</strong> why biodiversity is important and worthpreserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an estuary.Grade Levels9-12Teach<strong>in</strong>g Time4 (55 m<strong>in</strong>ute) class sessions + homeworkOrganization of <strong>the</strong> ActivityThis activity consists of 3 parts which help deepenunderstand<strong>in</strong>g of estuar<strong>in</strong>e systems:Investigat<strong>in</strong>g Habitats <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong><strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>Portrait of Life <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>BackgroundThis activity <strong>in</strong>troduces students to<strong>the</strong> amaz<strong>in</strong>g biodiversity of an estuar<strong>in</strong>eenvironment, focus<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> habitats <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay National Estuar<strong>in</strong>eResearch Reserve (RBNERR). The reserveis located at <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn end of <strong>the</strong> TenLife Science Module—Activity 3

Thousand Islands on <strong>the</strong> gulf coast of Florida and representsone of <strong>the</strong> few rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g undisturbed mangroveestuaries <strong>in</strong> North America. The total estimated surfacearea of open waters encompassed with<strong>in</strong> proposedboundaries is 70,000 acres, 64 percent of RBNERR. Therema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 40,000 acres are composed primarily of mangroves,fresh to brackish water marshes, and uplandhabitats.Rookery Bay has a surface area of 1,034 acres and amean depth of about 1 m. Sal<strong>in</strong>ities range from 18.5 to39.4 parts per thousand with lower values occurr<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> wet season from May through October. Highestvalues occur dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dry seasons (w<strong>in</strong>ter and spr<strong>in</strong>g)and can exceed those of <strong>the</strong> open Gulf of Mexico (35-36parts per thousand).Preparation• Download Google Earth, if you haven’t alreadydone so, and <strong>in</strong>stall it on your classroom computer(s) or computer lab mach<strong>in</strong>es http://earth.google.com/(Refer to Us<strong>in</strong>g Google Earth to Explore <strong>Estuaries</strong>, for abrief how-to guide.)• Arrange for students to access <strong>the</strong> Internet and/oro<strong>the</strong>r resources on organisms. For example, <strong>the</strong>University of Michigan Museum of Zoology’sGoogle EarthThis activity requires <strong>the</strong> use of Google Earth. Ifstudents have computer access, <strong>the</strong> use of Google Earth(http://earth.google.com/) can help <strong>the</strong>mdevelop spatial skills.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> Tutorial “Us<strong>in</strong>g Google Earth to Explore<strong>Estuaries</strong>” go to <strong>Estuaries</strong>.noaa.gov, click <strong>the</strong> tab titledCurriculum and <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> sub-tab titled Tutorials.Animal Diversity Web site:http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/<strong>in</strong>dex.html• Obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> poster paper for <strong>the</strong> concept maps <strong>in</strong>Part 2 and <strong>the</strong> poster board for <strong>the</strong> students’ organismprofiles <strong>in</strong> Part 3.• Make copies of <strong>the</strong> Student Read<strong>in</strong>g and Student Worksheet.• If feasible, assign <strong>the</strong> Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—Introduction toRookery Bay and Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an<strong>Estuary</strong> before beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> activity, as preparationfor Part 1.MaterialsStudentsNeed to work <strong>in</strong> a computer lab or with acomputer and projectorCopy of Student Read<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Estuary</strong> and WatershedCopy of Student Worksheet<strong>Estuary</strong> and Watershed, Student Data Sheet 1— Orient<strong>in</strong>g Yourself to <strong>the</strong> San Francisco<strong>Estuary</strong> and WatershedTeachers• large sheets of poster paper (for Part 2)• large pieces of poster board (for Part 3)Equipment:Computer lab orComputer and ProjectorCopy of Student Data Sheet 2 — Water QualityDataLife Science Module—Activity 32

ProcedurePart 1 — Investigat<strong>in</strong>g Habitats <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>1. Have students read <strong>the</strong> Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—Introductionto Rookery Bay and Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an<strong>Estuary</strong>.2. Show students <strong>the</strong>ir start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t (Rookery Bay NationalEstuar<strong>in</strong>e Research Reserve; 26° 01' 30.55 N,81° 43' 54.20 W) <strong>in</strong> Google Earth and have <strong>the</strong>mcomplete Part 1 of <strong>the</strong> Student Worksheet—<strong>Biodiversity</strong><strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>.If students are us<strong>in</strong>g Google Earth for <strong>the</strong> first time,show <strong>the</strong>m how to use <strong>the</strong> Search tool, how tozoom <strong>in</strong> and out to change view<strong>in</strong>g altitude, andhow to use <strong>the</strong> motion buttons to navigate around<strong>the</strong> image. (Refer to Us<strong>in</strong>g Google Earth to Explore <strong>Estuaries</strong>,available onl<strong>in</strong>e where you acquired this activity,for a brief how-to guide, or have students gothrough <strong>the</strong> “Navigat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Google Earth” tutorial athttp://earth.google.com/support/b<strong>in</strong>/answer.py?answer=176674)Discuss why <strong>the</strong> images seem to change, particularly<strong>the</strong> color and resolution of some of <strong>the</strong> images.3. Review and discuss <strong>the</strong> Part 1 tasks and questions.Part 2 — <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>National Science Education StandardsContent Standard A: Science as InquiryA3. Use technology and ma<strong>the</strong>matics to improve<strong>in</strong>vestigations and communications.A4. Formulate and revise scientific explanationsus<strong>in</strong>g logic and evidence.A6. Communicate and defend a scientific argument.Content Standard B: Physical ScienceB6. Interactions of energy and matterContent Standard C: Life ScienceC4. The <strong>in</strong>terdependence of organismsC5. Matter, energy, and organization <strong>in</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g systemsContent Standard F: Science <strong>in</strong> Personal andSocial PerspectivesF3. Natural ResourcesF4. Environmental qualityF5. Natural and human-<strong>in</strong>duced hazardsF6. Science and technology <strong>in</strong> local, national, andglobal challengesdescribes concept maps. If students are unfamiliarwith concept maps, consider draw<strong>in</strong>g a sample conceptmap on a general topic, such as your school.6. Have <strong>the</strong> student teams create <strong>the</strong>ir Rookery Bayconcept maps, start<strong>in</strong>g with a box that has “RookeryBay Reserve” and follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>structions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Concept Map section <strong>in</strong> Part 2 of <strong>the</strong> StudentWorksheet—<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>.4. Divide <strong>the</strong> class <strong>in</strong>to teams, distribute <strong>the</strong> largepaper, and expla<strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong>y will produce a largeconcept map that underscores <strong>the</strong> biodiversity and<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terrelationships of organisms <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamicestuar<strong>in</strong>e environment.5. Have students read <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>in</strong> Part 2 of <strong>the</strong>Student Worksheet—<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>, which7. When students are done with <strong>the</strong>ir concept maps,attach <strong>the</strong> maps to a board or wall and have adiscussion on <strong>the</strong> similarities and differences between<strong>the</strong> various maps.8. Have students answer <strong>the</strong> question to complete Part2 of <strong>the</strong> Student Worksheet—<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>.Life Science Module—Activity 3 3

Part 3 — Portrait of Life <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>: A WildlifeExhibit9. Assign or have students select one organism from anestuary to study <strong>in</strong> detail. You can have studentsdraw <strong>the</strong> name of an organism out of a bowl(proverbial hat…) or you can have <strong>the</strong>m choose oneorganism that <strong>the</strong>y would like to focus on.12. Allow students sufficient time to circulate and readall <strong>the</strong> class posters.13. Lead a discussion of <strong>the</strong> importance of biodiversity,us<strong>in</strong>g examples where low biodiversity was problematic,and review <strong>the</strong> tasks and questions of Part 3.10. Have students complete Part 3 of <strong>the</strong> Student Worksheet—<strong>Biodiversity</strong><strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong> and produce a posteron <strong>the</strong>ir organism.11. When students f<strong>in</strong>ish <strong>the</strong>ir posters, create a class exhibitto serve as a view<strong>in</strong>g area and post students’work.Check for Understand<strong>in</strong>g1. Use <strong>the</strong> concept maps from Part 2 as an assessment ofstudent understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> relationships betweenhabitats, characteristics of <strong>the</strong> habitats, and <strong>the</strong> speciesthat <strong>in</strong>habit <strong>the</strong> estuary.A simple way to do this is to give 1 po<strong>in</strong>t for each l<strong>in</strong>kon <strong>the</strong> concept map between two of <strong>the</strong> three variables.Then, award 2 po<strong>in</strong>ts for each double l<strong>in</strong>k (two l<strong>in</strong>esthat reveal a relationship). Add 3 po<strong>in</strong>ts for complex<strong>in</strong>terrelationships <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> concept map (3 or more l<strong>in</strong>escom<strong>in</strong>g from one box). Establish a class scale based on<strong>the</strong> total po<strong>in</strong>ts given for each poster.Optional Extension InquiriesAsk for permission to take samples of plants native to <strong>the</strong>estuary region and have student teams compile a pressedsample book. Have students organize <strong>the</strong>ir field collectionby creat<strong>in</strong>g a multi-stage classification and a dichotomouskey for <strong>the</strong> samples <strong>the</strong>y collected.2. Evaluate <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Exhibit posters as a summativeperformance assessment for this activity.3. Have a discussion with students after <strong>the</strong> WildlifeExhibit view<strong>in</strong>g has ended. Ask students:• Which animals or plants <strong>in</strong> Rookery Bay areendangered?• What conditions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estuary have causedpopulations of each of <strong>the</strong> endangered species todecl<strong>in</strong>e?• Are any actions be<strong>in</strong>g taken or projects underway toprotect <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g population and support itsrecovery?Life Science Module—Activity 34

Teacher Worksheet with AnswersActivity 3: <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>1a. Describe <strong>the</strong> estuary features and landforms you saw as you exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> Florida coast.Answer: Students should mention bays, <strong>in</strong>lets, wetlands, barrier beaches, and o<strong>the</strong>rs.1b. List <strong>the</strong> types of habitats you identified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay National Estuar<strong>in</strong>e Research Reserve.Answer: Upland forests, mangrove forest, salt marsh, and tidal flats habitats are evident.2. Were <strong>the</strong>re any animal species that were not l<strong>in</strong>ked to ano<strong>the</strong>r with at least one arrow?Answer: Each species should be have at least one connection to ano<strong>the</strong>r species and most will have more than one.3a. Which animals or plants <strong>in</strong> Rookery Bay are endangered?Answer: The Florida manatee is endangered. A rare and endangered species list for Rookery Bay can be found atwww.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/rookery/species.htm.3b. Choose one of <strong>the</strong> endangered animals and f<strong>in</strong>d out what conditions have caused its populations to decl<strong>in</strong>e. Areany actions be<strong>in</strong>g taken or projects underway to protect <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g population and support its recovery?Answer: Student answers will vary.Life Science Module—Activity 35

Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—1Activity 3: Introduction to Rookery Bay NERRLocated at <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn end of <strong>the</strong> Ten Thousand Islandson <strong>the</strong> gulf coast of Florida, Rookery Bay NationalEstuar<strong>in</strong>e Research Reserve (NERR) is a prime exampleof a nearly prist<strong>in</strong>e subtropical mangrove forested estuary.The Rookery Bay estuar<strong>in</strong>e ecosystem conta<strong>in</strong>s bays,<strong>in</strong>terconnected tidal embayments, lagoons and tidalstreams. Sources of freshwater dra<strong>in</strong>age <strong>in</strong>clude sloughs,strands, a series of tidal creeks and channels, and canals.A unique upland feature of <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay NERR andadjacent region are shell mounds. These are mostly refusesites used by aborig<strong>in</strong>al Indians. The mounds formprom<strong>in</strong>ent topographical features above <strong>the</strong> low-ly<strong>in</strong>gtidelands of <strong>the</strong> Reserve.The region is known for its commercially valuable fishesand shellfish, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g mullets, blue crabs and stonecrabs. Agriculture, eco-tourism, fish<strong>in</strong>g, and boat<strong>in</strong>g areimportant revenue sources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region, and <strong>the</strong> undevelopedareas of <strong>the</strong> reserve and <strong>the</strong> Aquatic Preserveare heavily used year-round.The core of <strong>the</strong> reserve is currently 12,500 acres of openwater, mangrove wetlands, and p<strong>in</strong>e and oak uplands.The state’s Rookery Bay Aquatic Preserve and Cape Romano/TenThousand Islands Aquatic Preserve are alsomanaged by <strong>the</strong> reserve, br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> total of state landsand water managed by <strong>the</strong> reserve to 112,000 acres.Figure 1. Rookery Bay seen through an arch of Mangrove treesLife Science Module—Activity 3

Figure 2. Many diverse habitats occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve and adjacent lands. Some of <strong>the</strong>se are: 1) P<strong>in</strong>e/CabbagePalm/Oak, 2) P<strong>in</strong>e Flatwoods, 3) Coastal Scrub, 4) Cypress Forest, 5) Freshwater Marsh, 6) Saltwater Marsh, 7)Mangrove Forests, 8) Coastal Strand, and 9) Open Water.• Adapted from http://nerrs.noaa.gov/RookeryBay/welcome.html andhttp://www.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/rookery/<strong>in</strong>fo.htmLife Science Module—Activity 3 2

Student Read<strong>in</strong>g—2Activity 3: <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>An estuary is a partially enclosed body of water, and itssurround<strong>in</strong>g coastal habitats, where saltwater from <strong>the</strong>ocean mixes with fresh water from rivers, streams, orgroundwater. In fresh water, <strong>the</strong> concentration of salts,or sal<strong>in</strong>ity, is nearly zero. The sal<strong>in</strong>ity of water <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ocean averages about 35 parts per thousand (ppt). Themixture of saltwater and freshwater <strong>in</strong> estuaries is calledbrackish water. An amaz<strong>in</strong>g number of plant and animalspecies have found ways to adapt to <strong>the</strong> dynamicand ever-chang<strong>in</strong>g environmental conditions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estuary.Some organisms have evolved special physical structuresto cope with chang<strong>in</strong>g sal<strong>in</strong>ity. The smooth cordgrassfound <strong>in</strong> salt marshes, for example, has special filters onits roots to remove salts from <strong>the</strong> water it absorbs. Thisplant also expels excess salt through its leaves.A rich array of habitats surrounds estuaries. Habitat typeis usually determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> local geology and climate.Some habitats associated with estuaries <strong>in</strong>clude:• salt marshes • mangrove forest• mudflats • tidal streams• rocky <strong>in</strong>tertidal shores • barrier beaches• sea grass bedsIn almost all estuaries, <strong>the</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity of <strong>the</strong> water changesconstantly over <strong>the</strong> tidal cycle. To survive <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se conditions,plants and animals liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> estuaries must beable to respond quickly to drastic changes <strong>in</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity.Plants and animals that can tolerate only slight changes<strong>in</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity are called stenohal<strong>in</strong>e. These organisms usuallylive <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r freshwater or saltwater environments. Moststenohal<strong>in</strong>e organisms cannot tolerate <strong>the</strong> rapid changes<strong>in</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity that occurs dur<strong>in</strong>g each tidal cycle <strong>in</strong> an estuary.Plants and animals that can tolerate a wide range of sal<strong>in</strong>itiesare called euryhal<strong>in</strong>e. These are <strong>the</strong> plants andanimals most often found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> brackish waters of estuaries.There are far fewer euryhal<strong>in</strong>e than stenohal<strong>in</strong>eorganisms because it requires a lot of energy and specializedadaptations to tolerate constantly chang<strong>in</strong>g sal<strong>in</strong>ities.Organisms that can do this are rare and special.Figure 3. Oysters have <strong>the</strong> ability to adapt to changes<strong>in</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity by open<strong>in</strong>g or clos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir shellsOysters and o<strong>the</strong>r bivalves, like mussels and clams, canlive <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> brackish waters of estuaries by adapt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>irbehavior to <strong>the</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g environment. Dur<strong>in</strong>g low tideswhen <strong>the</strong>y are exposed to low-sal<strong>in</strong>ity water, oystersclose up <strong>the</strong>ir shells and stop feed<strong>in</strong>g. Isolated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>irshells, oysters switch from aerobic respiration (breath<strong>in</strong>goxygen through <strong>the</strong>ir gills) to anaerobic respiration,which does not require oxygen. Hours later, when <strong>the</strong>high tides return and <strong>the</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity levels <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> water areconsiderably higher, <strong>the</strong> oysters open <strong>the</strong>ir shells andreturn to feed<strong>in</strong>g and breath<strong>in</strong>g oxygen.Unlike plants, which typically live <strong>the</strong>irwhole lives rooted to one spot, manyanimals that live <strong>in</strong> estuaries must change<strong>the</strong>ir behavior accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>gwaters’ sal<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>in</strong> order to survive. Blue crabsare good examples of animals that do this.Life Science Module—Activity 33

A Study of One Estuar<strong>in</strong>e Habitat — MangroveForestMangrove forests grow at tropical and subtropical latitudesnear <strong>the</strong> equator where <strong>the</strong> sea surface temperaturesnever fall below 16°C. Mangrove forests l<strong>in</strong>e abouttwo-thirds of <strong>the</strong> coastl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> tropical areas of <strong>the</strong>world. All mangrove trees are able grow <strong>in</strong> hypoxic(oxygen poor) soils where slow-mov<strong>in</strong>g waters allow f<strong>in</strong>esediments to accumulate. Mangrove forests can be recognizedby <strong>the</strong>ir dense tangle of prop roots that make<strong>the</strong> trees appear to be stand<strong>in</strong>g on stilts above <strong>the</strong> water.This tangle of roots helps to slow <strong>the</strong> movement of tidalwaters, caus<strong>in</strong>g even more sediments to settle out of <strong>the</strong>water and build up <strong>the</strong> muddy bottom. Mangrove forestsstabilize <strong>the</strong> coastl<strong>in</strong>e, reduc<strong>in</strong>g erosion from stormsurges, currents, waves and tides.<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Mangrove ForestThe mangrove forest is a habitat for many species. Itprovides nursery grounds for young fish, crustaceansand mollusks. Many fish feed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mangrove forests,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Snook, Mangrove Snapper, Tarpon, Jack,Sheepshead, Red Drum, Juvenile Blue Angelfish, L<strong>in</strong>edSeahorse, and Great Barracuda as well as shrimp andclams. An estimated 75% of <strong>the</strong> game fish and 90% of<strong>the</strong> commercial fish species <strong>in</strong> south Florida depend on<strong>the</strong> mangrove system.The branches of mangroves serve as roosts and rookeriesfor coastal and wad<strong>in</strong>g birds, such as <strong>the</strong> RoseateSpoonbill, Double-Crested Cormorant, Great Egret,Great Blue Heron, Osprey, Snowy Egret, Green Heron,and Greater Yellowlegs. O<strong>the</strong>r animals that shelter <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> mangroves are <strong>the</strong> American Coot, American Crocodile,Bald Eagle, Peregr<strong>in</strong>e Falcon, Eastern DiamondbackRattlesnake, and <strong>the</strong> Atlantic Saltmarsh Snake.Figure 4. Mangrove forests are common along <strong>the</strong>sou<strong>the</strong>rn coast of <strong>the</strong> United States.Three dom<strong>in</strong>ant species of mangrove tree are found <strong>in</strong>Florida. The red mangrove colonizes <strong>the</strong> seaward side of<strong>the</strong> forest and black mangroves are found fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>land.The zone <strong>in</strong> which black mangrove trees are found is onlyshallowly flooded dur<strong>in</strong>g high tides. White mangrovetrees face <strong>in</strong>land and dom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>the</strong> highest terra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>estuary. Tidal waters almost never flood <strong>the</strong> zone wherewhite mangrove trees grow.—Adapted fromoceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/estuaries/media/supp_estuar06b_mangrove.htmlFigure 5. Ospreys are secondary consumers. They feed almostentirely on fish <strong>the</strong>y capture from fresh or saltwater.Life Science Module—Activity 3 4

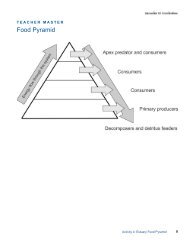

Above <strong>the</strong> water mangroves also shelter and supportsnails, periw<strong>in</strong>kles, crabs, spiders, Spanish moss, andRe<strong>in</strong>deer lichen. Below <strong>the</strong> water’s surface, often encrustedon <strong>the</strong> mangrove roots, are sponges, anemones,corals, oysters, mussels, starfish, crabs, and Florida Sp<strong>in</strong>ylobster.As you can see, a unique mix of mar<strong>in</strong>e and terrestrialspecies lives <strong>in</strong> mangrove forests. The still, sheltered watersamong <strong>the</strong> mangrove roots provide protectivebreed<strong>in</strong>g, feed<strong>in</strong>g, and nursery areas for a host of animalspecies important to commercial and recreational fisheries.Protect<strong>in</strong>g this habitat is truly a matter of nationalimportance.Animal species that <strong>in</strong>habit any habitat are classified asei<strong>the</strong>r primary producers, primary consumers, orsecondary consumers. Green plants, algae, and diatomsare examples of primary producers—organismsthat produce <strong>the</strong>ir own food through <strong>the</strong> process ofphotosyn<strong>the</strong>sis. Primary consumers like m<strong>in</strong>nows ando<strong>the</strong>r aquatic species eat <strong>the</strong> algae to provide <strong>the</strong>ir energyneeds.Figure 6. Producers and consumers <strong>in</strong> an estuar<strong>in</strong>e environment. (Nutrients and Florida's Coastal Waters: The L<strong>in</strong>ks BetweenPeople, Increased Nutrients and Changes to Coastal Aquatic Systems. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SG061. Published by <strong>the</strong> Florida SeaGrant College Program with support from <strong>the</strong> National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, Office of Sea Grant, U.S. Departmentof Commerce. Published for <strong>the</strong> University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences [SGEB-55]. October 2001.)Accessed: 2008-07-20.(Archived by WebCite ® at http://www.webcitation.org/5ZhWgbRvv)Life Science Module—Activity 3 5

Organisms such as larger fish that eat primary consumersare called secondary consumers. Birds of prey suchas ospreys are secondary or tertiary consumers, as <strong>the</strong>ydive <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> water to capture fish <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir talons.question of “walk<strong>in</strong>g lightly” on <strong>the</strong> Earth—a balance ofrespect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> natural changes that occur and ofprotect<strong>in</strong>g species and environments from wantonext<strong>in</strong>ction and destruction.Why is <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Important?The natural environment is <strong>the</strong> source of all ourresources for life. Environmental processes provide awealth of services to <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g world—air to brea<strong>the</strong>,water to dr<strong>in</strong>k, and food to eat, as well as materials touse <strong>in</strong> our daily lives and natural beauty to enjoy.A complex ecosystem like an estuary with a wide varietyof plants and animals tends to be more stable. A highlydiverse ecosystem is a sign of a healthy system. S<strong>in</strong>ce<strong>the</strong> entire liv<strong>in</strong>g world relies on <strong>the</strong> natural environment,especially humans, it is <strong>in</strong> our best <strong>in</strong>terest and<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest of future generations to conserve biodiversityand our resources.Life on Earth would not be <strong>the</strong> same if our planet’sbiodiversity were to be radically affected. <strong>Estuaries</strong> arecomplex ecosystems that are home for a number ofplants and animal species. The loss of a s<strong>in</strong>gle specieshas consequences for many o<strong>the</strong>rs liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> samehabitat.- Adapted from:URL:http://eco-onl<strong>in</strong>e.qld.edu.au/novascotia/whatsbio/importance.html.Accessed: 2008-07-30. (Archived by WebCite ® athttp://www.webcitation.org/5Zhq3RSh2)Some might argue that some species have becomeext<strong>in</strong>ct with no obvious effect on <strong>the</strong> environment. But<strong>the</strong> Earth’s systems are so complex that we are stilllearn<strong>in</strong>g about environmental processes and resourcesand <strong>the</strong> roles <strong>the</strong>y play. The careless loss of any part of<strong>the</strong> natural environment means that we may neverknow what use it was or could have been <strong>in</strong> terms offuture technologies, say, or for medical science, or <strong>in</strong>deedfor <strong>the</strong> health of <strong>the</strong> planet itself.It is important to understand that environments areconstantly chang<strong>in</strong>g. A healthy, robust environmentevolves and adapts to naturally chang<strong>in</strong>g conditions. Itis fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g to observe <strong>the</strong> far-reach<strong>in</strong>g effects thateven small changes can make and <strong>the</strong> importance ofgenetic diversity for species to adapt, survive andevolve.Preservation of biodiversity is not necessarily aboutpreserv<strong>in</strong>g everyth<strong>in</strong>g currently <strong>in</strong> existence. It is more aLife Science Module—Activity 36

Student WorksheetActivity 3: <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>Student Name:Part 1: Investigat<strong>in</strong>g Habitats <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>In this activity, you will explore <strong>the</strong> habitats that compose <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay Reserve near Naples, Florida.Open Google Earth and enter <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g coord<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Search W<strong>in</strong>dow: 26° 01' 30.55 N, 81° 43' 54.20 W.Zoom <strong>in</strong> to an Eye altitude of 400 m. You should see <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> Field Station (build<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vic<strong>in</strong>ity of <strong>the</strong> longdock) of <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay Reserve.Fly south along <strong>the</strong> coast at a view<strong>in</strong>g altitude of about 4 km.1a. Describe <strong>the</strong> estuary features and landforms you saw as you exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> Florida coast.Life Science Module—Activity 37

Keep go<strong>in</strong>g down <strong>the</strong> coast. You will pass a series of bays: Johnson, East Marco, Goodland, Turtle, and Rookery toname some of <strong>the</strong> major ones. Stop when you arrive at <strong>the</strong> region that is bounded by Faka Union Bay and FakahatcheeBay.Zoom <strong>in</strong>to this region and exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> type of habitat that surrounds <strong>the</strong>se bays. Can you locate this region on <strong>the</strong>map of <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay Reserve given below?Figure 7. Map of <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay NERR1b. List <strong>the</strong> types of habitats you identified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay Reserve. In <strong>the</strong> first column, list <strong>the</strong> habitatyou identified. In <strong>the</strong> second column, identify <strong>the</strong> characteristics of each habitat. In <strong>the</strong> third column, notewhe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> habitat is land (terrestrial) or water (aquatic). In <strong>the</strong> fourth column, note special challenges to liv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> each habitat to plant and animal species.Life Science Module—Activity 3 8

Habitat TypeName of Habitat Characteristics Terrestrial or Aquatic ChallengesLife Science Module—Activity 3 9

Part 2: <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Concept MapEvery plant and animal that exists <strong>in</strong> an estuary has a role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ecosystem. Species depend on each o<strong>the</strong>r for food,for shelter, or o<strong>the</strong>r life processes. In this part of <strong>the</strong> activity, you will produce a concept map that shows how <strong>the</strong>estuar<strong>in</strong>e environment supports <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terrelationships of <strong>the</strong> plants and animals that reside <strong>in</strong> it.IntroductionEvery topic can be broken down <strong>in</strong>to a set of dist<strong>in</strong>ct factors. Th<strong>in</strong>k about topics such as acid ra<strong>in</strong>, clean<strong>in</strong>g yourroom, putt<strong>in</strong>g on a dance, <strong>the</strong> water cycle, or do<strong>in</strong>g homework. You can break each of <strong>the</strong>se down <strong>in</strong>to separatecomponents, which toge<strong>the</strong>r describe <strong>the</strong> larger topic. A concept map is a visual way to show how a topic’s componentsor factors are connected or related. In fact, you can th<strong>in</strong>k of concept maps as a visual way to outl<strong>in</strong>e a topic.The first step <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g a concept map is to identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual elements <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> topic. Just as when youtell a story, you must first identify all <strong>the</strong> elements before you beg<strong>in</strong>—<strong>the</strong> characters, <strong>the</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>gs, and <strong>the</strong> plot. Aconcept map helps people identify which ideas are essential to a topic and which are secondary or only weakly connected.The second step <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g a concept map is to show how <strong>the</strong> parts relate to one ano<strong>the</strong>r.The follow<strong>in</strong>g guidel<strong>in</strong>es will help you make concept maps that are descriptive and complete.Concepts, objects, places, or processes appear <strong>in</strong> boxes. Most often, <strong>the</strong>se words are nouns.Concept, Object, or Process(Usually a noun)Example:FoodArrows connect one box to ano<strong>the</strong>r. The arrow’s direction <strong>in</strong>dicates how <strong>the</strong> reader should progress through <strong>the</strong> ideas.Words describ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> actions and relationships appear on or just above <strong>the</strong> arrows connect<strong>in</strong>g different boxes. Most often,<strong>the</strong>se labels are verbs.Action or relationshipExample:FoodSuppliesSuppliesEnergyRaw MaterialsWhen label<strong>in</strong>g an arrow, us<strong>in</strong>g a noun (or a phrase such as "results <strong>in</strong>") is a clue that you can probably break <strong>the</strong> down<strong>the</strong> flow <strong>in</strong>to more components and ref<strong>in</strong>e what is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> boxes.If a box does not connect to <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> topic be<strong>in</strong>g described <strong>in</strong> a concept map, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re is no need to draw a connection.When it is complete, you should be able read a concept map as if it were a paragraph or even a story. Select a box, andread along a sequence of arrows. The boxed words and arrow labels should make sense and expla<strong>in</strong> how <strong>the</strong> ideas <strong>in</strong>terconnect.In <strong>the</strong> supernova example, you can trace <strong>the</strong> sequence describ<strong>in</strong>g how stars and planets form by start<strong>in</strong>g at anybox.Life Science Module—Activity 3 10

Concept MapCreate a concept map.• Beg<strong>in</strong> your map with a s<strong>in</strong>gle box with Rookery Bay Reserve <strong>in</strong> it.• Include <strong>the</strong> major habitats that exist with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estuary (examples: Mangrove forest, tidal flats, etc.).• Include characteristics of each habitat (see Habitat Table), sal<strong>in</strong>ity and o<strong>the</strong>r physical and chemical properties of<strong>the</strong> water (shallow, deep, fresh water, pH, etc.).• Include <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g plant and animal species: algae, Mangrove trees, clams, oysters, shrimp, periw<strong>in</strong>kles,horseshoe crabs, blue crabs, sea turtles, Snook, Mangrove Snapper, Tarpon, Juvenile Blue Angelfish, L<strong>in</strong>ed Seahorse,Barracuda, Great Blue Heron, Osprey, Snowy Egret, Green Heron, Greater Yellowlegs, American Coot,American Crocodile, Bald Eagle, Peregr<strong>in</strong>e Falcon, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, and Florida manatee.• If possible, consult <strong>the</strong> Rookery Bay field guide for a list of more species to add to your map:http://www.rookerybay.org/Field-Guide.html.• Indicate which species are primary producers, primary consumers, and secondary consumers.Question2. Were <strong>the</strong>re any animal species that were not l<strong>in</strong>ked to ano<strong>the</strong>r species with at least one arrow?Life Science Module—Activity 311

Part 3 — Portrait of Life <strong>in</strong> an <strong>Estuary</strong>: A Wildlife ExhibitIn this Part of <strong>the</strong> activity, you will explore <strong>the</strong> life of a s<strong>in</strong>gle animal or plant species and describe how <strong>the</strong> speciesadapts to conditions with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estuary. You will ei<strong>the</strong>r be assigned an organism or allowed to select one that <strong>in</strong>terestsyou from this estuary system.Produce a poster about your animal or plant. Include <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g:• A clear title, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> name of your organism;• The names of <strong>the</strong> students on your team;• A series of pictures from <strong>the</strong> Internet or magaz<strong>in</strong>es of your organism;• Information and, when feasible, pictures on your organism’s life cycle, preferred habitat, adaptations to chang<strong>in</strong>gconditions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estuary (such as sal<strong>in</strong>ity and temperature), primary and secondary food sources, and whe<strong>the</strong>r<strong>the</strong> species is endangered or not; and• References for where you got your images and <strong>in</strong>formation (e.g. <strong>the</strong> URLs of <strong>the</strong> Web sites).Hang your poster as part of a class exhibit on estuary wildlife.Walk around <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ished class exhibit and read all of <strong>the</strong> posters.Life Science Module—Activity 312