Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty as an Alternative to Penetrating ...

Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty as an Alternative to Penetrating ...

Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty as an Alternative to Penetrating ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ophthalmic Technology Assessment<strong>Deep</strong> <strong>Anterior</strong> <strong>Lamellar</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong><strong>Alternative</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Penetrating</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong>A Report by the Americ<strong>an</strong> Academy of OphthalmologyWilliam J. Reinhart, MD, 1 David C. Musch, PhD, MPH, 2 Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, 3 W. Barry Lee, MD, 4Stephen C. Kaufm<strong>an</strong>, MD, PhD, 5 Roni M. Shtein, MD 6Objective: To review the published literature on deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (DALK) <strong>to</strong> compare DALKwith penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (PK) for the outcomes of best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), refractive error,immune graft rejection, <strong>an</strong>d graft survival.Methods: Searches of the peer-reviewed literature were conducted in the PubMed <strong>an</strong>d the Cochr<strong>an</strong>e Librarydatab<strong>as</strong>es. The searches were limited <strong>to</strong> citations starting in 1997, <strong>an</strong>d the most recent search w<strong>as</strong> in May 2009. Thesearches yielded 1024 citations in English-l<strong>an</strong>guage journals. The abstracts of these articles were reviewed, <strong>an</strong>d 162articles were selected for possible clinical relev<strong>an</strong>ce, of which 55 were determined <strong>to</strong> be relev<strong>an</strong>t <strong>to</strong> the <strong>as</strong>sessmen<strong>to</strong>bjective.Results: Eleven DALK/PK comparative studies (level II <strong>an</strong>d level III evidence) were identified that compared theresults of DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK procedures directly; they included 481 DALK eyes <strong>an</strong>d 501 PK eyes. Of those studiesreporting vision <strong>an</strong>d refractive data, there w<strong>as</strong> no signific<strong>an</strong>t difference in BSCVA between the 2 groups in 9 of thestudies. There w<strong>as</strong> no signific<strong>an</strong>t difference in spheroequivalent refraction in 6 of the studies, nor w<strong>as</strong> there <strong>as</strong>ignific<strong>an</strong>t difference in pos<strong>to</strong>perative <strong>as</strong>tigmatism in 9 of the studies, although the r<strong>an</strong>ge of <strong>as</strong>tigmatism w<strong>as</strong> oftenlarge for both groups. Endothelial cell density (ECD) stabilized within 6 months after surgery in DALK eyes. Endothelialcell density values were higher in the DALK groups in all studies at study completion, <strong>an</strong>d, in general, the ECDdifferences between DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK groups were signific<strong>an</strong>t at all time points at 6 months or longer after surgery forall of the studies reporting data.Conclusions: On the b<strong>as</strong>is of level II evidence in 1 study <strong>an</strong>d level III evidence in 10 studies, DALK is equivalent<strong>to</strong> PK for the outcome me<strong>as</strong>ure of BSCVA, particularly if the surgical technique yields minimal residual host stromalthickness. There is no adv<strong>an</strong>tage <strong>to</strong> DALK for refractive error outcomes. Although improved graft survival in DALK h<strong>as</strong>yet <strong>to</strong> be demonstrated, pos<strong>to</strong>perative data indicate that DALK is superior <strong>to</strong> PK for preservation of ECD. Endothelialimmune graft rejection c<strong>an</strong>not occur after DALK, which may simplify long-term m<strong>an</strong>agement of DALK eyes comparedwith PK eyes. As <strong>an</strong> extraocular procedure, DALK h<strong>as</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t theoretic safety adv<strong>an</strong>tages, <strong>an</strong>d it is a good optionfor visual rehabilitation of corneal dise<strong>as</strong>e in patients whose endothelium is not compromised.Fin<strong>an</strong>cial Disclosure(s): Proprietary or commercial disclosure may be found after the references.Ophthalmology 2011;118:209–218 © 2011 by the Americ<strong>an</strong> Academy of Ophthalmology.The Americ<strong>an</strong> Academy of Ophthalmology prepares OphthalmicTechnology Assessments <strong>to</strong> evaluate new <strong>an</strong>d existingprocedures, drugs, <strong>an</strong>d diagnostic <strong>an</strong>d screening tests. The goalof <strong>an</strong> Ophthalmic Technology Assessment is <strong>to</strong> evaluate thepeer-reviewed scientific literature, <strong>to</strong> distill what is well establishedabout the technology, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>to</strong> help refine the import<strong>an</strong>tquestions <strong>to</strong> be <strong>an</strong>swered by future investigations. After appropriatereview by all contribu<strong>to</strong>rs, including legal counsel,<strong>as</strong>sessments are submitted <strong>to</strong> the Academy’s Board of Trusteesfor consideration <strong>as</strong> official Academy statements. The purposeof this <strong>as</strong>sessment is <strong>to</strong> review the published literature on deep<strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (DALK) <strong>to</strong> compare it withpenetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (PK) for the outcomes of bestspectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), refractive error,rejection, <strong>an</strong>d graft survival.Background<strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty refers <strong>to</strong> a corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t, orgraft, in which the entire thickness of the cornea is replaced.In conventional posterior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (LK) <strong>an</strong>d thenewer endothelial kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (EK) procedures, the innerlayers of the cornea are tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>ted. Vari<strong>an</strong>ts of these© 2011 by the Americ<strong>an</strong> Academy of Ophthalmology ISSN 0161-6420/11/$–see front matterPublished by Elsevier Inc.doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.002209

Ophthalmology Volume 118, Number 1, J<strong>an</strong>uary 2011procedures include deep lamellar EK, Descemet’s stripping(au<strong>to</strong>mated) EK (DSEK or DSAEK), Descemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>eEK, <strong>an</strong>d Descemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>e au<strong>to</strong>mated EK. Thehealth of the corneal endothelium is the main criterion fordeciding if <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior or posterior LK procedure is indicated.Dise<strong>as</strong>es involving the corneal endothelium c<strong>an</strong> bem<strong>an</strong>aged with EK or PK, <strong>an</strong>d those dise<strong>as</strong>es involving boththe corneal endothelium <strong>an</strong>d the corneal stroma usuallyrequire PK. In conventional <strong>an</strong>terior LK, only a portion ofthe corneal thickness is replaced.The first successful hum<strong>an</strong> partial penetrating cornealtr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t w<strong>as</strong> performed by Zirm 1 in 1905 using <strong>as</strong>pring-driven trephine originally designed by von Hippel2 in 1888 for performing partial LK. Over the l<strong>as</strong>t halfof the 20th century, PK became the st<strong>an</strong>dard of care form<strong>an</strong>aging the surgical correction of most axial dise<strong>as</strong>esof the cornea. <strong>Lamellar</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty w<strong>as</strong> usually reservedfor the tec<strong>to</strong>nic surgical correction of less common cornealconditions, such <strong>as</strong> peripheral ect<strong>as</strong>i<strong>as</strong>, perforatedulcers, <strong>an</strong>d traumatic loss of tissue. However, there h<strong>as</strong>always been a cadre of ophthalmic surgeons, includingPaufique, 3 Malbr<strong>an</strong>, 4 Anwar, 5 <strong>an</strong>d others, who have usedlamellar corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t surgery <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> alternative <strong>to</strong>PK for the optical correction of axial corneal dise<strong>as</strong>eswith normal corneal endothelium, such <strong>as</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>conus,stromal corneal dystrophies, <strong>an</strong>d corneal scars from traumaticinjury or infection. In the 1970s, there w<strong>as</strong> incre<strong>as</strong>edinterest in lamellar corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tation. 6 As aresult of the technical difficulty of the procedure <strong>an</strong>d thereduced pos<strong>to</strong>perative acuity typically following LK,however, PK h<strong>as</strong> remained the domin<strong>an</strong>t corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tprocedure for the optical correction of cornealdise<strong>as</strong>e.There h<strong>as</strong> been incre<strong>as</strong>ed interest in newer <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar corneal procedures for vision res<strong>to</strong>ration, <strong>as</strong>noted by publications in peer-reviewed journals, articlesin industry-supported publications, <strong>an</strong>d instructionalcourses both in private venues <strong>an</strong>d at educational meetingsof ophthalmological org<strong>an</strong>izations. One of the mostpublicized of the various <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar corneal procedures,DALK, involves the removal of central cornealstroma while leaving host corneal endothelium <strong>an</strong>d Descemet’smembr<strong>an</strong>e (DM) intact. Descemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>emay or may not be exposed in DALK procedures. Themajor theoretic adv<strong>an</strong>tages of DALK over PK proceduresare the absence of potential corneal endothelial cell immunerejection <strong>an</strong>d the expected retention of most recipientcorneal endothelial cells in DALK surgery comparedwith the rapid decre<strong>as</strong>e in donor corneal endothelial celldensity (ECD) after PK surgery.Several surgical techniques have been developed <strong>to</strong> accomplishremoval of all, or almost all, of the corneal stromain a lamellar dissection bed, which is the most critical <strong>as</strong>pec<strong>to</strong>f a successful DALK. A brief overview of DALK techniqueswill be summarized in this article.When Sugita <strong>an</strong>d Kondo 7 first presented their techniquefor baring DM, they called the technique “deep <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty,” or DLK. Because that term laterbecame widely used <strong>to</strong> refer <strong>to</strong> the diffuse lamellar keratitis<strong>as</strong>sociated with LASIK surgery, in this <strong>as</strong>sessment the abbreviationDALK is used <strong>to</strong> refer <strong>to</strong> deep <strong>an</strong>terior LKprocedures in general. Anwar <strong>an</strong>d Teichm<strong>an</strong>n 8 suggestedthat the term “maximum depth <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty”be used <strong>to</strong> refer <strong>to</strong> baring of DM. In this <strong>as</strong>sessment,the terms “DALK” <strong>an</strong>d “maximum depth DALK” (MD-DALK) are used. The literature does not always distinguishbetween c<strong>as</strong>es in which DM baring w<strong>as</strong> pl<strong>an</strong>ned (i.e., MD-DALK) but not achieved because of perforation, surgeoncaution, <strong>an</strong>d so forth, <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>as</strong>es in which enough deepcorneal stroma w<strong>as</strong> left in the surgical bed <strong>to</strong> qualify <strong>as</strong> aDALK but not <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> MD-DALK. In other techniques thatare discussed, DM exposure is not the goal of the DALK,although DM exposure is occ<strong>as</strong>ionally achieved, <strong>an</strong>d thisdistinction is not usually identified.The perimeter of the DALK bed is usually defined usinga trephine diameter of 7 <strong>to</strong> 8.5 mm <strong>to</strong> partially cut throughthe <strong>an</strong>terior stromal fibers, but not deep enough <strong>to</strong> enter the<strong>an</strong>terior chamber, depending on the host corneal diameter<strong>an</strong>d the corneal dise<strong>as</strong>e being treated. This partial-thicknesstrephination may be performed initially, <strong>as</strong> in the hydrodelaminationtechnique of Sugita <strong>an</strong>d Kondo 7 or the big-bubbletechnique of Anwar <strong>an</strong>d Teichm<strong>an</strong>n; 9 after exp<strong>an</strong>sion of thecorneal stroma with air, <strong>as</strong> in the air injection technique ofArchila, 10 <strong>as</strong> modified by Morris et al 11 <strong>an</strong>d Coombes etal; 12 or after the limbal dissection of a deep lamellar pocketthat is then filled with <strong>an</strong> ophthalmic viscosurgical device(OVD) using the Melles technique. 13Sugita <strong>an</strong>d Kondo’s 7 method of direct dissection afterpartial trephination involves removal of the <strong>an</strong>terior twothirds of corneal stroma, followed by injection of fluid in<strong>to</strong>the remaining stromal bed <strong>an</strong>d spatula delamination forremoval of the deeper stromal layers. This is followed byhydrodelamination <strong>an</strong>d exposure of DM in the central 5 mmof the trephine bed. Rostron’s direct dissection methodinvolves exp<strong>an</strong>ding the corneal thickness with air injectionbefore trephination <strong>an</strong>d then removing the overlying stromaby direct dissection. If DM is detached during the airinjection, all overlying stroma will be removed. As doSugita <strong>an</strong>d Kondo, Anwar first performs a partial-depthtrephine cut but then forcibly injects air deep in the stromalbed <strong>to</strong> detach DM, producing a “big bubble” that greatlyfacilitates the removal of all stroma in the trephine bed. Thedirect dissection DALK techniques using air or fluid oftenresult in baring of DM. Sugita <strong>an</strong>d Kondo’s techniquerequires peeling off the final thin layer of deep stroma, atle<strong>as</strong>t in the central 5 mm or so, where<strong>as</strong> the big-bubbletechnique, when successful, results in separation of DMfrom the deep corneal stroma. Otherwise, layer-by-layerdeep dissection with the aid of air, fluid, or <strong>an</strong> OVD may berequired <strong>to</strong> attempt DM exposure.The Melles technique requires a limbal approach <strong>an</strong>ddepends on the surgeon’s visual determination of the depthof the lamellar dissection. A full-corneal diameter pre-DMpocket is created by lamellar dissection <strong>an</strong>d filled with <strong>an</strong>OVD, <strong>an</strong>d then trephination is performed <strong>to</strong> remove the<strong>an</strong>terior stromal but<strong>to</strong>n. The thickness of the residual stromalbed is dependent on the surgeon’s ability <strong>to</strong> judgevisually how close the lamellar dissection blade c<strong>an</strong> come <strong>to</strong>DM without puncturing it.210

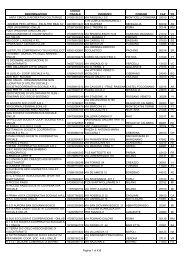

Reinhart et al <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>Anterior</strong> <strong>Lamellar</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong>Rostron’s DALK procedures generally use fullthickness,lyophilized donor lenticules, where<strong>as</strong> Sugita <strong>an</strong>dKondo’s 7 earlier efforts used cryolathed lenticules. Glycerin-cryopreservedcorneal tissue h<strong>as</strong> also been acceptable. 14One study specifically compared eyes that had receivedlyophilized donor corne<strong>as</strong> or donor corne<strong>as</strong> kept in OptisolGS (Bausch & Lomb, Inc., Rochester, NY) <strong>an</strong>d found nostatistical differences between the 2 methods of donor cornealpreservation. 15 According <strong>to</strong> the recent literature, mostsurgeons use full-thickness donor lenticules obtained fromcorneal sclera rims preserved in intermediate s<strong>to</strong>rage media(e.g., Optisol GS) or org<strong>an</strong> culture media, <strong>as</strong> is common inEurope. The donor endothelium c<strong>an</strong> be removed with a drysurgical sponge. However, m<strong>an</strong>y surgeons also remove DM.In either c<strong>as</strong>e, the posterior face of the donor graft will havea smooth interface apposed <strong>to</strong> the smooth bed of the exposed(bared) host DM. The <strong>an</strong>tigenic load of the donor isalso decre<strong>as</strong>ed by removing the endothelial cells. In DALKprocedures where some residual stroma remains, the interfacewill not be <strong>as</strong> regular, <strong>an</strong>d presumably even less regularif the donor lenticule h<strong>as</strong> also been obtained through surgicaldissection, such <strong>as</strong> described by Tsubota et al 16 <strong>an</strong>dP<strong>an</strong>da et al. 17Question for AssessmentThe objective of this <strong>as</strong>sessment is <strong>to</strong> address the followingquestion: How does DALK compare with PK for the outcomesof BSCVA, refractive error, rejection, <strong>an</strong>d graftsurvival?Description of EvidenceA search of the peer reviewed English-l<strong>an</strong>guage literaturew<strong>as</strong> conducted in the PubMed datab<strong>as</strong>e on December 14,2006, <strong>an</strong>d Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 1, 2007, <strong>an</strong>d a search of the Cochr<strong>an</strong>eLibrary datab<strong>as</strong>e w<strong>as</strong> conducted on December 18, 2006, <strong>an</strong>dOc<strong>to</strong>ber 1, 2007, limited <strong>to</strong> citations starting in 1997. Keywords in the search were the MeSH heading corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tationcombined with text words deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellarkera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty or DALK or deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty orDescemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>e baring or maximum depth <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. The authors <strong>as</strong>sessed the 236 citationsresulting from the electronic searches <strong>an</strong>d selected 88citations that definitely or potentially met the inclusioncriteria.The authors obtained the full copy of these 88 articles forfurther <strong>as</strong>sessment. The reviewers were not m<strong>as</strong>ked <strong>to</strong> trialresults or publication details. The authors reviewed the full tex<strong>to</strong>f these articles <strong>to</strong> <strong>as</strong>sess their inclusion according <strong>to</strong> theselection criteria. One additional article w<strong>as</strong> identified fromreview of <strong>an</strong> article reference list. The authors selected 42articles for methodological review, <strong>an</strong>d they chose <strong>an</strong> additional19 articles <strong>to</strong> send <strong>to</strong> the first author for <strong>as</strong>sist<strong>an</strong>ce inwriting the first draft. These 19 articles were review articles,single-c<strong>as</strong>e reports of complications, or single-c<strong>as</strong>e reports oftechnique, <strong>an</strong>d they did not receive methodological review.The methodologist <strong>as</strong>signed ratings of level of evidence<strong>to</strong> each of the selected articles. A level I rating w<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>signed<strong>to</strong> well-designed <strong>an</strong>d well-conducted r<strong>an</strong>domized clinicaltrials; a level II rating w<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>signed <strong>to</strong> well-designed c<strong>as</strong>econtrol<strong>an</strong>d cohort studies or poor-quality r<strong>an</strong>domized clinicaltrials; <strong>an</strong>d a level III rating w<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>signed <strong>to</strong> c<strong>as</strong>e series,c<strong>as</strong>e reports, <strong>an</strong>d poor-quality c<strong>as</strong>e-control or cohort studies.Two studies were r<strong>an</strong>domized controlled trials that wererated <strong>as</strong> level II evidence because of insufficient power, lackof m<strong>as</strong>king, <strong>an</strong>d a less rigorous r<strong>an</strong>domization method. 15,18All other articles were comparative <strong>an</strong>d noncomparativec<strong>as</strong>e series, prospective <strong>an</strong>d retrospective, or c<strong>as</strong>e reports<strong>an</strong>d were rated <strong>as</strong> level III evidence.An updated search, conducted on May 28, 2009, includedthe additional search term penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty(MeSH <strong>an</strong>d text) <strong>an</strong>d retrieved 788 citations, of which <strong>an</strong>additional 73 possibly relev<strong>an</strong>t studies were identified <strong>an</strong>dreviewed. Of these, 13 were judged relev<strong>an</strong>t. In addition,surveill<strong>an</strong>ce of the literature identified more recent relev<strong>an</strong>tpublications. These additional studies were rated <strong>as</strong> level IIIevidence.Published ResultsDetailed descriptions <strong>an</strong>d Tables (1–6) of the outcomesfrom the included studies are included in the Appendix(available at http://aaojournal.org).Eleven published studies were identified in which theoperative <strong>an</strong>d pos<strong>to</strong>perative results of DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK procedureswere compared directly. Only 1 study 18 w<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>signeda level II rating, <strong>an</strong>d the other 10 studies were rated<strong>as</strong> level III. All were single-institution studies, often withone operative surgeon, <strong>an</strong>d attempts were made <strong>to</strong> controlfor common fac<strong>to</strong>rs such <strong>as</strong> diagnosis or age. These 11studies are particularly useful for comparing the visual,refractive, early pos<strong>to</strong>perative ECD results, <strong>an</strong>d surgicalcomplications of the 2 procedures. These data are presentedin Table 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org). The DALKdata from 10 of these 11 studies were then abstracted <strong>an</strong>dcompiled along with DALK data from 31 other clinicalstudies (1 study rated <strong>as</strong> level II <strong>an</strong>d 30 rated <strong>as</strong> level III) <strong>to</strong>obtain a broader view of the operative complications ofDALK, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> pos<strong>to</strong>perative visual, refractive, <strong>an</strong>d ECDdata. The results of those 41 studies are presented, in part,in Table 2 (available at http://aaojournal.org).The 11 identified clinical comparative DALK/PK studiesinclude data on a <strong>to</strong>tal of 481 eyes that had DALK <strong>an</strong>d 501eyes that had PK. Eight studies had 26 eyes in eachgroup, 17–24 one study had 41 DALK <strong>an</strong>d 43 PK eyes, 25 onestudy had 135 DALK <strong>an</strong>d 76 PK eyes, 26 <strong>an</strong>d one study had150 in each group. 27 Seven of the studies 19–24,26 enrolledonly patients with kera<strong>to</strong>conus, one study enrolled onlypatients with lattice or macular corneal dystrophy, 25 <strong>an</strong>d theremaining 3 studies included various corneal stromaldise<strong>as</strong>es. 17,18,27Table 3 (available at http://aaojournal.org) lists the reportedcomplications for the 1843 eyes in the 41 studies forpl<strong>an</strong>ned DALK procedures only. The most common operativecomplication w<strong>as</strong> DM perforation(s), which occurredin 11.7% of c<strong>as</strong>es. Air or g<strong>as</strong> injections in<strong>to</strong> the <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber at the time of surgery or in the pos<strong>to</strong>perative period211

Ophthalmology Volume 118, Number 1, J<strong>an</strong>uary 2011c<strong>an</strong> result in loss of corneal endothelial cells, g<strong>as</strong>-inducedpupillary block, or a failure of a DM detachment <strong>to</strong> resolve.Pos<strong>to</strong>perative double <strong>an</strong>terior chamber, presumably alsorelated <strong>to</strong> operative perforations of DM, required a subsequen<strong>to</strong>perative intervention in 2.2% of c<strong>as</strong>es <strong>an</strong>d, when notsuccessful, w<strong>as</strong> the most common cause of delayed PKconversions in 0.4%. There were 5 (0.3%) repeat DALKprocedures. Donor lamellar graft recipient-bed interfacecomplications such <strong>as</strong> interface haze, DM wrinkling, <strong>an</strong>dinterface v<strong>as</strong>cularization were uncommon at 0.7%, 0.5%<strong>an</strong>d 0.5%, respectively. These complications are unique <strong>to</strong>DALK procedures, where<strong>as</strong> the remaining complicationsnoted in Table 3 (available at http://aaojournal.org) wereindividually less th<strong>an</strong> 0.5% <strong>an</strong>d could have occurred withPK or DALK.Of the 11 comparative studies, there w<strong>as</strong> no signific<strong>an</strong>tdifference in the pos<strong>to</strong>perative BSCVA between the DALK<strong>an</strong>d PK groups in 6 studies, 17,18,22,23,25,26 <strong>an</strong>d there w<strong>as</strong>better BSCVA in the DALK group in one study 27 <strong>an</strong>d betterBSCVA in the PK group in 4 studies. 19–21,24 The onestudy 27 reporting better pos<strong>to</strong>perative vision in the DALKgroup had the largest number of eyes in each group (150/150). Overall, there w<strong>as</strong> no signific<strong>an</strong>t difference betweenspherical refractive error or <strong>as</strong>tigmatism between the DALK<strong>an</strong>d PK groups.Twenty-seven of the additional 31 studies listed in Table2 (available at http://aaojournal.org) presented data aboutpos<strong>to</strong>perative visual acuity, refractive correction, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>as</strong>tigmatismof DALK eyes. There w<strong>as</strong> no signific<strong>an</strong>t differencein pos<strong>to</strong>perative visual acuity between DALK or PK eyes <strong>as</strong>a group, although there w<strong>as</strong> a tendency for lower visualacuity in DALK eyes in which DM w<strong>as</strong> not bared <strong>an</strong>dresidual stroma in the bed exceeded 10% of <strong>to</strong>tal stromalthickness.Immune-mediated donor-graft rejection c<strong>an</strong> be cl<strong>as</strong>sified<strong>as</strong> epithelial, stromal, endothelial, or some combination ofthese. Because corneal endothelium is not replaced inDALK, donor endothelial immune-medicated rejection c<strong>an</strong>no<strong>to</strong>ccur <strong>as</strong> it c<strong>an</strong> in PK. Stromal graft rejection c<strong>an</strong> alsooccur during the pos<strong>to</strong>perative period after DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK.There were 18 immune rejections recorded (1.0%) for the1843 DALK eyes reported in Table 2 (available at http://aaojournal.org). One study 28 reported 7 of 29 patients withDALK for kera<strong>to</strong>conus who had graft rejections, 2 of whomhad progressive v<strong>as</strong>cularization of the graft interface withopacification. One recent study, 29 not included in Table 2(available at http://aaojournal.org), of 129 consecutive eyesof 121 patients with DALK for kera<strong>to</strong>conus recorded 14 of129 episodes (10.9%) of subepithelial graft rejection <strong>an</strong>d 4of 129 episodes (3.1%) of stromal graft rejection, all successfullytreated with a 3- <strong>to</strong> 6-week course of <strong>to</strong>picalcorticosteroids. The majority of graft rejection episodes(n13) occurred in the first year after surgery <strong>an</strong>d in patientswith a his<strong>to</strong>ry of vernal kera<strong>to</strong>conjunctivitis (66.3%).Eighteen of the 129 eyes had a his<strong>to</strong>ry of vernal kera<strong>to</strong>conjunctivitisthat w<strong>as</strong> inactive at the time of surgery.Six of the 11 studies in the DALK/PK comparison group(Table 1; available at http://aaojournal.org) evaluated pos<strong>to</strong>perativeECD of the host corneal endothelium for theDALK groups <strong>an</strong>d of the donor graft endothelium for thePK groups. All demonstrated signific<strong>an</strong>tly higher ECD inthe DALK groups: at 12 months pos<strong>to</strong>peratively in 2 studies,17,20 at 24 months in one study, 18 at 3 years in onestudy, 25 <strong>an</strong>d at all intervals up <strong>to</strong> 5 years in the one study. 26The ECD data for the DALK/PK comparative studies highlightsignific<strong>an</strong>t differences between these surgical techniques(Table 1; available at http://aaojournal.org), withconsistently higher ECD in post-DALK eyes compared withpost-PK eyes.DiscussionThe adv<strong>an</strong>tages of DALK over PK surgery are <strong>as</strong> follows:● Immune rejection of the corneal endothelium c<strong>an</strong>no<strong>to</strong>ccur.● The procedure is extraocular <strong>an</strong>d not intraocular.● Topical corticosteroids c<strong>an</strong> usually be discontinuedearlier with DALK.● There is minor loss of ECD.● Compared with PK, DALK may have superior resist<strong>an</strong>ce<strong>to</strong> rupture of the globe after blunt trauma.● Sutures c<strong>an</strong> be removed earlier with DALK.The most obvious adv<strong>an</strong>tage of DALK is that the hostcorneal endothelium is not subject <strong>to</strong> immune rejection inDALK. Larger grafts approaching the limbus c<strong>an</strong> be usedwith DALK if the goal is complete removal of ectatic tissuein kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Normal-risk patients undergoing PK whoare phakic are generally tapered off of <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroidsin 6 months, although continuing a daily <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroiddrop for <strong>an</strong> additional 6 months provided additionalprotection against immunologic rejection in a large,prospective r<strong>an</strong>domized interventional trial of 406 eyes. 30However, this adv<strong>an</strong>tage of DALK over PK is not <strong>as</strong> great<strong>as</strong> one might expect, because immune rejection after PK forkera<strong>to</strong>conus is less likely <strong>an</strong>d kera<strong>to</strong>conus is the most commonindication for DALK. The major long-term adv<strong>an</strong>tageof DALK surgery over PK relates <strong>to</strong> long-term preservationof host corneal endothelial cells <strong>as</strong> me<strong>as</strong>ured by specularmicroscopy <strong>an</strong>d reported <strong>as</strong> ECD.Certain patients require PK, such <strong>as</strong> patients with kera<strong>to</strong>conuswho also have coexisting Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy.Patients with corneal scarring from conditions such<strong>as</strong> herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, microbialcorneal ulcers, or macular corneal dystrophy who have acompromised corneal endothelium should have PK surgery.However, in the presence of a relatively normal host cornealendothelium, not having <strong>to</strong> use long-term <strong>to</strong>pical, periocular,or systemic immunosuppressive agents <strong>to</strong> m<strong>an</strong>age thegraft is a definite adv<strong>an</strong>tage for DALK, especially if thepatient is a corticosteroid responder or is phakic.<strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty avoids the intraocular,open-sky segment of the PK procedure. Complications,including positive pressure, iris prolapse, <strong>an</strong>d choroidaleffusion/hemorrhage, are completely avoided with DALK.Tr<strong>an</strong>smission of bacterial infection from donor <strong>to</strong> recipientshould theoretically remain limited <strong>to</strong> keratitis rather th<strong>an</strong>endophthalmitis.212

Reinhart et al <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>Anterior</strong> <strong>Lamellar</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong><strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty c<strong>an</strong> reduce ECD,especially if microperforations occur, <strong>an</strong>d even more so if<strong>an</strong>terior chamber injection of g<strong>as</strong> is required <strong>to</strong> m<strong>an</strong>age DMdetachments or double <strong>an</strong>terior chamber. 7,31–34 Corneal endotheliumc<strong>an</strong> be compromised by pupillary block <strong>an</strong>gleclosure after <strong>an</strong>terior chamber g<strong>as</strong> injection or by the airbubble itself. With recognition of these exceptions, continuedor accelerated loss of ECD after DALK surgery doesnot seem <strong>to</strong> occur after 6 months <strong>as</strong> it does post-PK.Endothelial cell density loss after the immediate pos<strong>to</strong>perativetime period is likely <strong>to</strong> mimic the gradual ECD decre<strong>as</strong>eof a normal cornea.Because <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids c<strong>an</strong> usually be discontinued3 <strong>to</strong> 4 months after DALK, there is a lower incidence ofcorticosteroid-<strong>as</strong>sociated intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation.With DALK, there is incre<strong>as</strong>ed wound strength comparedwith the PK wound, which is subjected <strong>to</strong> the prolongeduse of <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids <strong>to</strong> prevent immunerejection, <strong>an</strong>d there is decre<strong>as</strong>ed risk of cataract progression<strong>an</strong>d less compromised local ocular surface immunity.Traumatic rupture of PK wounds months <strong>to</strong> decades aftersurgery is a potential complication 35 that c<strong>an</strong> be cat<strong>as</strong>trophic.There is a theoretic adv<strong>an</strong>tage of DALK woundsover PK wounds, <strong>an</strong>d there are clinical reports of traumaticdehiscence of DALK wounds that suggest that the injuriesare less severe th<strong>an</strong> might have been expected of PK eyes. 36It is difficult <strong>to</strong> prove this <strong>as</strong>sertion at this time because ofthe smaller numbers <strong>an</strong>d shorter pos<strong>to</strong>perative follow-upavailable on DALK eyes. However, <strong>an</strong> incidence of globerupture of 1.8% (36/1962), of which 35 received PK (2.0%)<strong>an</strong>d one w<strong>as</strong> a DALK eye (0.5%), w<strong>as</strong> reported in a seriesof 1962 consecutive kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ties (PK, 1776 eyes; DALK,186 eyes) between 1998 <strong>an</strong>d 2006. 35Sutures c<strong>an</strong> be removed earlier on DALK eyes. Unlessperm<strong>an</strong>ent sutures are used, PK eyes do not have a stablerefraction until all sutures have been removed, which insome c<strong>as</strong>es may not occur until several years after surgery.Although early reports suggested that sutures could be removedin DALK eyes <strong>as</strong> early <strong>as</strong> 3 months pos<strong>to</strong>perativelybecause of the lower burden of corticosteroid use <strong>an</strong>d betterwound <strong>an</strong>a<strong>to</strong>my, 6 <strong>to</strong> 12 months seems more the norm.However, once sutures are removed, further refractive surgeryc<strong>an</strong> be performed earlier <strong>an</strong>d presumably with lessconcern of wound rupture in DALK eyes. One study suggeststhat <strong>as</strong>tigmatic kera<strong>to</strong><strong>to</strong>my incisions behave somewhatdifferently in DALK eyes th<strong>an</strong> in PK eyes. 37 <strong>Penetrating</strong>kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty eyes often do not have a stable refraction foryears after surgery; wound strength is always of concernwhen performing refractive procedures such <strong>as</strong> LASIK becauseof the wound stressing effects of the IOP-incre<strong>as</strong>ingsuction ring required for surgery.The adv<strong>an</strong>tages of PK over DALK are <strong>as</strong> follows:● <strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty c<strong>an</strong> be used <strong>to</strong> treat cornealconditions that involve the endothelium, such <strong>as</strong>Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy, pseudophakic<strong>an</strong>d aphakic corneal edema, posterior polymorphouscorneal dystrophy, <strong>an</strong>d congenital hereditary cornealendothelial dystrophies, although EK (DSEK orDSAEK) may now be preferred.● <strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty c<strong>an</strong> treat penetrating cornealtrauma, especially if there is loss of corneal tissue.● <strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty c<strong>an</strong> be used if there is scarringdown <strong>to</strong> the level of DM, such <strong>as</strong> postacutehydrops in kera<strong>to</strong>conus, old penetrating central cornealinjuries, <strong>an</strong>d severe postinfectious corneal ulcers. Inthe presence of <strong>an</strong> adequate ECD, the non-DM–baringDALK techniques may be used <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> alternative <strong>to</strong> PK.● <strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty c<strong>an</strong> be used if DM is notexposed in the visual axis, <strong>an</strong>d vision in those with PKmay be superior.● <strong>Penetrating</strong> kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty is a more familiar operativeprocedure for most corneal surgeons.There are geographic <strong>an</strong>d social differences in the indicationsfor corneal surgery, but m<strong>an</strong>y corneal dise<strong>as</strong>es are<strong>as</strong>sociated with compromised corneal endothelium, whichme<strong>an</strong>s that PK, or EK, will account for most requests fordonor corneal tissue directed <strong>to</strong> <strong>an</strong>y given eye b<strong>an</strong>k. Also, inkera<strong>to</strong>conus eyes that have had previous hydrops, traumaticpenetrating injuries <strong>to</strong> the central cornea, or severe microbialinfections with residual scarring down <strong>to</strong> DM, thebig-bubble technique for DALK will not usually be successful.Other direct dissection DALK techniques, which leavesome residual cornea, c<strong>an</strong> be considered in these c<strong>as</strong>es,although final vision may not be <strong>as</strong> good <strong>as</strong> after PK. Ifcorneal hydrops complicating kera<strong>to</strong>conus h<strong>as</strong> occurred <strong>an</strong>dDALK without DM exposure is performed, pressuredependentstromal edema after surgery h<strong>as</strong> been describedthat cleared with IOP-lowering medication <strong>an</strong>d time. 38However, MD-DALK h<strong>as</strong> been reported for a patient with ahis<strong>to</strong>ry of hydrops-complicating kera<strong>to</strong>conus. 39 If DM isexposed in the visual axis, <strong>an</strong>d there are no DM folds in thevisual axis, then visual acuity is similar for DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK.If a signific<strong>an</strong>t amount of pre-Descemet’s stroma is left inthe recipient bed, then visual acuity in DALK eyes may becompromised. 19,22,26,32,40 In these c<strong>as</strong>es, removal of theDALK graft followed by excimer l<strong>as</strong>er pho<strong>to</strong>ablation or thebig-bubble technique <strong>to</strong> remove the remaining stromal tissue<strong>an</strong>d replacement of the DALK graft c<strong>an</strong> improve visualacuity 26,40 <strong>an</strong>d prevent the need for a subsequent PK.Alió 40 m<strong>an</strong>aged 4 eyes with poor vision after DALKusing the Melles technique, lifted the DALK donor graft <strong>as</strong>long <strong>as</strong> 2 years pos<strong>to</strong>peratively, <strong>an</strong>d exposed DM with abig-bubble technique, improving 6-month BSCVA <strong>to</strong> 20/25in 3 patients <strong>an</strong>d 20/32 in one patient. However, when DMc<strong>an</strong>not be exposed, or if there is signific<strong>an</strong>t scarring of thedeep corneal stroma, m<strong>an</strong>y surgeons may choose <strong>to</strong> use PK<strong>as</strong> the primary procedure.There is a definite learning curve for both PK <strong>an</strong>d DALKprocedures, although most corneal surgeons already possessthe acquired skills for PK surgery. The operative time forDALK is usually longer th<strong>an</strong> for PK, <strong>an</strong>d both proceduresrequire more operative time th<strong>an</strong> DSEK surgery because ofthe extensive suturing of the DALK or PK donor graft.The complications unique <strong>to</strong> DALK are <strong>as</strong> follows:● Ruptures of DM.● Large lamellar splits in DM.● Microperforations of DM.● Double <strong>an</strong>terior chamber.213

Ophthalmology Volume 118, Number 1, J<strong>an</strong>uary 2011● Endothelial cell loss secondary <strong>to</strong> air/synthetic g<strong>as</strong>.● Interface haze or irregularity if all stroma is not removedin the visual axis.● Interface debris, hemorrhage, v<strong>as</strong>cularization, microbialinfections, <strong>an</strong>d epithelial ingrowth.● Wrinkles of DM or the residual stroma <strong>an</strong>d DM layer.● Sequestered OVD in the interface.● Mydri<strong>as</strong>is from air block glaucoma usually complicating<strong>an</strong>terior chamber g<strong>as</strong> injection <strong>to</strong> treat DMdetachment.● Recurrence of stromal cornea dystrophy in the residualbed.● Occ<strong>as</strong>ional re-epithelialization problems.The most common complication involves puncturingDM with either small perforations of 1 mm or less, ormacroperforations that usually lead <strong>to</strong> immediate operativeconversion <strong>to</strong> PK. This c<strong>an</strong> occur with either big-bubbletechniques using air, OVD, or fluid injection, or micro ormacro DM perforation during direct dissection using <strong>as</strong>urgical blade with or without the injection of fluid, air, orOVD injection. Conversion <strong>to</strong> a conventional PK may beadvisable unless the perforation is small.<strong>Lamellar</strong> splits in DM with stromal pressure dissectionusing air, fluid, or OVD are uncommon <strong>an</strong>d may not berecognized by the operating surgeon, but they do incre<strong>as</strong>ethe risk of DM perforation because of the thinness of theremaining DM. If a perforation occurs, but a DALK iscompleted, then air or other g<strong>as</strong> placement in the <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber <strong>to</strong> tamponade the perforation may lead <strong>to</strong> additionalECD loss, g<strong>as</strong> pupillary block with a fixed dilatedpupil, 41,42 or eventual failure of the DALK graft <strong>an</strong>d theneed for a delayed conversion <strong>to</strong> PK. Although perforationsare common at <strong>an</strong> average rate of 11.7%, intraoperative PKconversions of 2.0% <strong>an</strong>d delayed PK conversions of 0.4%suggest that most DALK c<strong>as</strong>es will be completed <strong>as</strong>pl<strong>an</strong>ned. If a DM perforation occurs before DM h<strong>as</strong> beenexposed in the central optical zone of 5 mm or so, residualstroma may be left <strong>an</strong>d the donor graft placed on <strong>to</strong>p, withpossible reduced visual acuity from residual stroma in thissituation.Microperforations of DM that do not preclude a lamellaronlay graft c<strong>an</strong> occur during DALK, although there is a riskof pos<strong>to</strong>perative DM detachment <strong>an</strong>d pseudo double <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber formation. Double <strong>an</strong>terior chamber is usuallya consequence of DM perforations, but h<strong>as</strong> also been describedin the absence of known perforations. This also maypersist if the endothelium h<strong>as</strong> not been removed from thedonor graft <strong>an</strong>d may complicate subsequent cataract surgerywith DM detachment. 43 Endothelial cell loss secondary <strong>to</strong>air/synthetic g<strong>as</strong> after <strong>an</strong>terior chamber injection <strong>to</strong> m<strong>an</strong>ageintraoperative DM tears or pos<strong>to</strong>perative double <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber may occur. 44Interface haze is rarely a problem with DM-baring procedures<strong>an</strong>d sometimes even experienced observers c<strong>an</strong>notdistinguish between a PK <strong>an</strong>d a DALK eye if DM h<strong>as</strong> beenexposed in the entire recipient bed. Interface haze maycause glare or decre<strong>as</strong>ed visual acuity. Interface debris,hemorrhage from host stromal v<strong>as</strong>cularization, interfacev<strong>as</strong>cularization, microbial infections, <strong>an</strong>d interface epithelialingrowth are rare complications. 22,45,46 Wrinkles of DMare more common in kera<strong>to</strong>conus eyes with adv<strong>an</strong>ced cones,presumably from compression of the cone when placing thedonor graft. 47 Wrinkles may also contribute <strong>to</strong> glare ordecre<strong>as</strong>ed vision. If noted at the time of surgery, m<strong>an</strong>ipulatingthe donor graft may displace the wrinkles out of thevisual axis <strong>an</strong>d decre<strong>as</strong>e their effect on vision.Retained OVD c<strong>an</strong> complicate the Melles or limbalpocket techniques where <strong>an</strong> OVD is used <strong>to</strong> exp<strong>an</strong>d thelimbal entr<strong>an</strong>ce pocket dissection <strong>to</strong> enable safe trephination.48 Often OVD is also used <strong>to</strong> reexp<strong>an</strong>d the collapsed airbubble in the big-bubble techniques before removing theremaining stroma. In <strong>an</strong>y c<strong>as</strong>e, the surgeon needs <strong>to</strong> bediligent in gently irrigating OVD from the lamellar bedbefore placing the donor graft <strong>to</strong> avoid potential donor graftedema or donor failure.Pos<strong>to</strong>perative DM detachment or a double <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber leads <strong>to</strong> poor vision from <strong>an</strong> edema<strong>to</strong>us graft <strong>an</strong>dthe need <strong>to</strong> inject air or <strong>an</strong>other g<strong>as</strong> in<strong>to</strong> the <strong>an</strong>terior chamber<strong>to</strong> tamponade the tear. Larger or inferior tears are moredifficult <strong>to</strong> tamponade with g<strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong>d may require suturereattachment or delayed conversion <strong>to</strong> PK. Complicationsof a large g<strong>as</strong> bubble in the <strong>an</strong>terior chamber include loss ofendothelial cells; air block glaucoma, which, in its mostsevere form, c<strong>an</strong> result in perm<strong>an</strong>ent pupillary mydri<strong>as</strong>isdue <strong>to</strong> iris ischemia, iris peripheral <strong>an</strong>terior synechiae, <strong>an</strong>dglaucomflecken because of <strong>an</strong>terior lens epithelial/lens corticalinfarcts (a group of complications usually referred <strong>to</strong> <strong>as</strong>“Urrets–Zavalia syndrome”); 49 <strong>an</strong>d, rarely, ischemic damage<strong>to</strong> the optic nerve or retina. These complications arerelated <strong>to</strong> elevated IOP <strong>an</strong>d are likely also related <strong>to</strong> theduration of the IOP elevation. Prompt diagnosis of thepupillary block glaucoma <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>agement with pupil dilationor paracentesis <strong>to</strong> reduce the size of the g<strong>as</strong> bubble,deepen the <strong>an</strong>terior chamber, <strong>an</strong>d eliminate the pupillaryblock will often prevent these complications.Recurrence of the corneal stromal dystrophies in the<strong>an</strong>terior portion of a corneal graft is expected for PK orDALK. However, recurrence in the interface h<strong>as</strong> been aproblem with LASIK surgery <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong> also occur withDALK. It is suspected that recurrence of a stromal dystrophysuch <strong>as</strong> lattice dystrophy in the deep lamellar bed is due<strong>to</strong> retained host stroma <strong>an</strong>d would be unlikely with theDM-baring techniques.Occ<strong>as</strong>ional re-epithelialization problems c<strong>an</strong> occur ifcryolathed or lyophilized donor lamellar tissue is used,although re-epithelialization c<strong>an</strong> also complicate PK whenthe epithelium is often not viable after longer corneal donors<strong>to</strong>rage times.Complications unique <strong>to</strong> PK are <strong>as</strong> follows:● Immune rejection of donor corneal endothelium.● Prolonged <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroid use necessary in somec<strong>as</strong>es.● Microbial endophthalmitis.● Trephine complications (iris damage, damage <strong>to</strong> thecrystalline lens, <strong>an</strong>d retained DM).● Open eye complications (positive vitreous pressure,expulsive choroidal hemorrhage, <strong>an</strong>d damage <strong>to</strong> theiris <strong>an</strong>d/or lens).214

Reinhart et al <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>Anterior</strong> <strong>Lamellar</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong>● <strong>Penetrating</strong> wound complications (flat <strong>an</strong>terior chamberfrom wound leak, iris synechiae <strong>to</strong> wound, <strong>an</strong>dpoor vertical wound apposition).● Elevated IOP from retained OVD.● <strong>Anterior</strong> chamber epithelial ingrowth.● Primary donor graft endothelial failure.● Accelerated donor graft endothelial cell loss (instrumenttrauma <strong>to</strong> the donor endothelium, trauma <strong>to</strong> theendothelium at surgery from iris or lens contact, <strong>an</strong>dpos<strong>to</strong>perative biph<strong>as</strong>ic accelerated loss).Immune corneal endothelial rejection c<strong>an</strong> be a majorproblem with high-risk corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t recipients, usuallyinvolving signific<strong>an</strong>t corneal stromal v<strong>as</strong>cularization, inflammation,<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>terior segment abnormalities. These eyesare occ<strong>as</strong>ional c<strong>an</strong>didates for DALK if the host endotheliumis normal, <strong>as</strong> it might be in ocular surface chemical injuries,ocular mucous membr<strong>an</strong>e pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnsonsyndrome, inactive interstitial keratitis with corneal scarringfrom varicella zoster virus or herpes simplex virus, <strong>an</strong>dv<strong>as</strong>cularized corne<strong>as</strong> after treatment for microbial keratitis.<strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty or even a therapeuticLK would be the preferred procedure if ocular surfaceproblems c<strong>an</strong> be m<strong>an</strong>aged. However, for kera<strong>to</strong>conus, immunerejection is not a major problem, because in kera<strong>to</strong>conusa graft rarely fails <strong>as</strong> the result of immune endothelialrejection if treated promptly <strong>an</strong>d appropriately. Whether theaccelerated long-term loss of ECD in PK is related <strong>to</strong>subclinical immune endothelial rejection or other causes h<strong>as</strong>not yet been determined.Prolonged <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroid use may be needed insome c<strong>as</strong>es with recurrent immunologic graft reactions.Corticosteroid-induced IOP incre<strong>as</strong>es may require use of<strong>to</strong>pical glaucoma medications or filtration surgery <strong>to</strong> controlthe IOP. There may be loss of vision from secondaryglaucoma, <strong>an</strong>d the patient may not be able <strong>to</strong> wear contactlenses during times of signific<strong>an</strong>t immunosuppression of theocular surface with <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids because of theincre<strong>as</strong>ed risk of infectious keratitis. There is also <strong>an</strong> incre<strong>as</strong>edcost <strong>as</strong>sociated with prolonged use of <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroidor glaucoma medications.Some of the complications unique <strong>to</strong> PK, such <strong>as</strong> microbialendophthalmitis, expulsive choroidal hemorrhage, <strong>an</strong>depithelial downgrowth, c<strong>an</strong> be dev<strong>as</strong>tating. These severecomplications are fortunately rare, particularly for phakicPK surgery that would usually be the alternative <strong>to</strong> DALKsurgery (because most eyes with kera<strong>to</strong>conus, nonpenetratingcorneal scars, herpes simplex virus, corneal scars, <strong>an</strong>d soforth are phakic).Complications related <strong>to</strong> the <strong>an</strong>terior chamber penetratingnature of PK surgery are also uncommon in experiencedh<strong>an</strong>ds, although when they do occur, they c<strong>an</strong> result incompromised visual outcomes.Complications common <strong>to</strong> PK <strong>an</strong>d DALK include thefollowing:● Ametropi<strong>as</strong>, <strong>as</strong>tigmatism of excessive amount, irregular<strong>as</strong>tigmatism.● Suture-related problems (sterile inflammation, microbialabscess, problems with epithelialization, prematureloosening, induced <strong>as</strong>tigmatism, delayed absorption,<strong>an</strong>d unpredictable breakage).● Immune donor epithelial <strong>an</strong>d stromal rejection.● Recurrence of corneal dystrophies.● Corneal ect<strong>as</strong>ia (recurrent kera<strong>to</strong>conus) of the graft,progressive host ect<strong>as</strong>ia in kera<strong>to</strong>conus eyes.● Donor endothelial cell loss in PK <strong>an</strong>d loss of host ECDin DALK, especially with DM perforations or <strong>an</strong>teriorchamber injection of air or g<strong>as</strong>.● Decre<strong>as</strong>ed resist<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>to</strong> globe rupture from blunt oculartrauma; usually the tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t wound remains theweakest part of the eyeball tunic.● Ocular surface dise<strong>as</strong>e.● Donor-<strong>to</strong>-host tr<strong>an</strong>smission of infection.Sutures c<strong>an</strong> be removed much earlier in DALK proceduresth<strong>an</strong> in PK, potentially leading <strong>to</strong> fewer suture-relatedproblems after DALK. Stromal <strong>an</strong>d epithelial immune rejectionc<strong>an</strong>not occur in those DALK procedures wherecryolathed or lyophilized donor corneal tissue h<strong>as</strong> been used<strong>to</strong> prepare the lamellar donor tissue because all kera<strong>to</strong>cytes<strong>an</strong>d epithelial cells are killed in the processing of the donortissue. However, most surgeons use corneal tissue preservedin short- or intermediate-term corneal preservation media,which usually preserves stromal kera<strong>to</strong>cytes <strong>an</strong>d, <strong>to</strong> a variabledegree, donor corneal epithelium. Stromal graft rejections,which are uncommon in the first place, become morerare <strong>as</strong> pos<strong>to</strong>perative time incre<strong>as</strong>es.In general, low-risk PK eyes with a diagnosis such <strong>as</strong>kera<strong>to</strong>conus are usually tapered off <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroidsby 6 months after surgery, <strong>an</strong>d corticosteroid-related glaucomais rarely a major m<strong>an</strong>agement problem. However, fora few patients with repeated immune graft rejections, therequired use of corticosteroids for immunosuppression c<strong>an</strong>result in corticosteroid-induced glaucoma <strong>an</strong>d posterior subcapsularcataract formation. The need for <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroidsin DALK eyes is unusual after 6 months pos<strong>to</strong>peratively.Even if corticosteroids are needed <strong>to</strong> treatsubepithelial infiltrates or stromal graft rejection in DALKeyes, <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids rarely have <strong>to</strong> be used forextended periods of time if there is no other source ofinflammation.Corneal dystrophies are known <strong>to</strong> recur after PK, usuallyinvolving the <strong>an</strong>terior part of the graft, <strong>an</strong>d they would beexpected <strong>to</strong> recur in similar f<strong>as</strong>hion after <strong>an</strong>terior lamellarcorneal procedures including DALK.Late pos<strong>to</strong>perative corneal ect<strong>as</strong>ia after DALK h<strong>as</strong> beenreported. 50 This w<strong>as</strong> a true kera<strong>to</strong>conus recurrence in aDALK cornea from lyophilized donor tissue in a schizophrenicpatient with habitual eye rubbing, <strong>an</strong> apparent causeof recurrent kera<strong>to</strong>conus, 51 <strong>an</strong>d a repeat DALK w<strong>as</strong> successful.Late-onset kera<strong>to</strong>conus h<strong>as</strong> also been reported forPK in kera<strong>to</strong>conus eyes. True kera<strong>to</strong>conus <strong>as</strong> a complicationof a PK h<strong>as</strong> been documented, 52 although most c<strong>as</strong>es described<strong>as</strong> late-onset kera<strong>to</strong>conus are probably due <strong>to</strong> continuedect<strong>as</strong>ia of a portion of the residual host cornea,usually inferiorly, <strong>an</strong>d is not true kera<strong>to</strong>conus where thegraft itself undergoes central thinning <strong>an</strong>d ect<strong>as</strong>ia. It remains<strong>to</strong> be determined whether kera<strong>to</strong>conus after a PK or aDALK graft is due <strong>to</strong> undiagnosed kera<strong>to</strong>conus in the donor215

Ophthalmology Volume 118, Number 1, J<strong>an</strong>uary 2011cornea, patient fac<strong>to</strong>rs such <strong>as</strong> biochemical abnormalities ofhost epithelium, stromal kera<strong>to</strong>cytes, or behavior such <strong>as</strong>eye rubbing <strong>an</strong>d contact lens wear. The more common causeof so-called recurrent kera<strong>to</strong>conus, continued thinning ofthe host cornea, is not e<strong>as</strong>ily addressed, but sometimesresection of a crescent of ectatic host cornea c<strong>an</strong> reduce<strong>as</strong>tigmatism <strong>to</strong> acceptable levels. Late ect<strong>as</strong>ia of graft–hostjunction, especially inferiorly, is not uncommon after PKfor kera<strong>to</strong>conus. This may reflect incomplete removal ofectatic tissue at the time of PK. A theoretic adv<strong>an</strong>tage ofDALK is the freedom <strong>to</strong> use larger grafts that approach thelimbus <strong>to</strong> help avoid this late complication. A 2-step, 2-diametertechnique h<strong>as</strong> been described <strong>to</strong> obtain DALK diametersof 9.5 <strong>to</strong> 11.0 mm if the initial diameter of 7.75 mmis successful. 53Ocular surface dise<strong>as</strong>e, such <strong>as</strong> dry eye, neurotrophic,neuroparalytic, epithelial stem-cell dysfunction, or otherdise<strong>as</strong>es, c<strong>an</strong> be a problem with either procedure, althoughLK procedures generally are less difficult <strong>to</strong> m<strong>an</strong>age becauseimmune endothelial rejection is not a fac<strong>to</strong>r <strong>an</strong>d<strong>an</strong>ti-rejection medication is generally less crucial.Conclusions <strong>an</strong>d Future ResearchThe objective of this review w<strong>as</strong> <strong>to</strong> compare DALK withPK for the outcomes of BSCVA, refractive error, rejection,<strong>an</strong>d graft survival. One level II study <strong>an</strong>d level III evidenceindicate that DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK have similar outcomes in termsof BSCVA <strong>an</strong>d refractive error. Exposure of DM or minimizationof residual stroma seems <strong>to</strong> be <strong>as</strong>sociated withbetter visual outcome in DALK. If residual stroma in thesurgical bed is minimal (25–65 m), vision may becomparable between the groups: If residual stroma isthicker, or if DM wrinkles or haze is present, vision may beless in the DALK eyes <strong>as</strong> a group, but not less th<strong>an</strong> 1 lineof Snellen visual acuity on average. Astigmatism <strong>an</strong>dametropia remain a problem for both PK <strong>an</strong>d DALK. Epithelial<strong>an</strong>d stromal immune rejection reactions of the donortissue c<strong>an</strong> occur with either procedure <strong>an</strong>d are usually e<strong>as</strong>ilym<strong>an</strong>aged with <strong>to</strong>pical corticosteroids. However, immunerejection reactions against donor graft endothelium c<strong>an</strong>no<strong>to</strong>ccur with DALK surgery, but they are a definite risk forPK <strong>an</strong>d may occur <strong>an</strong>y time during the lifetime of the graft.Each donor endothelial rejection reaction may result indecre<strong>as</strong>ed ECD or failure of the graft. The immune rejectionreactions themselves <strong>an</strong>d the immunosuppressive treatmentfor the acute rejection reactions or the prevention of rejectionmay lead <strong>to</strong> corticosteroid-<strong>as</strong>sociated IOP elevation insusceptible patients, acceleration of cataract ch<strong>an</strong>ges, decre<strong>as</strong>edwound healing, <strong>an</strong>d compromised local immunity,thereby providing <strong>an</strong> adv<strong>an</strong>tage of DALK over PK. Sufficientevidence remains <strong>to</strong> be gathered before a definitiveconclusion c<strong>an</strong> be reached about improved graft survivalafter DALK compared with after PK.If ECD is used <strong>as</strong> a proxy for graft survival, there aresubst<strong>an</strong>tial data from level III studies <strong>an</strong>d a level II studythat at <strong>an</strong>y pos<strong>to</strong>perative point in time DALK eyes havehigher ECD th<strong>an</strong> PK eyes. Because kera<strong>to</strong>conus is thedise<strong>as</strong>e most commonly treated using 1 of these 2 procedures<strong>an</strong>d kera<strong>to</strong>conus recipients tend <strong>to</strong> be young <strong>an</strong>dhealthy with a long life expect<strong>an</strong>cy, the preservation ofendothelial cells in DALK surgery may provide a majoradv<strong>an</strong>tage that will only become apparent within timeframes more relev<strong>an</strong>t <strong>to</strong> these patients, that is, decades. AsDALK procedures incre<strong>as</strong>e in number <strong>an</strong>d extended followupbecomes available, data on ECD <strong>an</strong>d graft survival c<strong>an</strong>be compared with existent data on populations with PK.R<strong>an</strong>domized clinical trials comparing DALK <strong>an</strong>d PK areneeded, but they are difficult <strong>an</strong>d costly <strong>to</strong> implement. TheDutch <strong>Lamellar</strong> Corneal Tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tation Study h<strong>as</strong> enrolled28 patients in each arm of a r<strong>an</strong>domized clinical trial that iscurrently being conducted <strong>to</strong> compare DALK with PK <strong>an</strong>dposterior LK with PK. 54 The primary outcome me<strong>as</strong>ure isthe discard rate of donor corne<strong>as</strong>, with secondary outcomeme<strong>as</strong>ures of visual acuity, <strong>as</strong>tigmatism, stray-light evaluation,contr<strong>as</strong>t sensitivity, endothelial cell loss, incidence ofendothelial rejection, vision-related quality of life, <strong>an</strong>d patientsatisfaction. Surgeons or patients who believe that thevisual <strong>an</strong>d refractive results of PK <strong>an</strong>d DALK are the samebut the rate of endothelial cell loss over time is signific<strong>an</strong>tlydifferent might view a r<strong>an</strong>domized prospective study comparingthe 2 techniques <strong>as</strong> unacceptable, <strong>an</strong>d it could bedifficult <strong>to</strong> enroll patients. It is difficult <strong>to</strong> conduct a triallarge enough <strong>to</strong> evaluate the secondary outcome me<strong>as</strong>ureslisted above. An observational study with well-st<strong>an</strong>dardizedoutcome <strong>as</strong>sessment may be more fe<strong>as</strong>ible. Any futureDALK trials should include imaging techniques <strong>to</strong> me<strong>as</strong>ureresidual posterior cornea stroma in the donor bed when DMexposure h<strong>as</strong> not been fully obtained <strong>to</strong> more fully elucidatethe relationship between BSCVA <strong>an</strong>d residual cornealstroma.References1. Zirm EK. Eine erfolgreiche <strong>to</strong>tale Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>tik (A successful<strong>to</strong>tal kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty). 1906. Refract Corneal Surg 1989;5:258–61.2. von Hippel A. Eine neue Methode der Hornhauttr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tation.Albrecht von Graefes Arch Ophthalmol 1888;34:108–30.3. Paufique L. Les greffes corneennes lamellaires therapeutiques.Bull Mem Soc Fr Ophtalmol 1949;62:210–3.4. Malbr<strong>an</strong> ES. Corneal dystrophies: a clinical, pathological, <strong>an</strong>dsurgical approach. 28 Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture.Am J Ophthalmol 1972;74:771–809.5. Anwar M. Technique in lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Tr<strong>an</strong>s OphthalmolSoc U K 1974;94:163–71.6. Richard JM, Pa<strong>to</strong>n D, G<strong>as</strong>set AR. A comparison of penetratingkera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>an</strong>d lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty in the surgical m<strong>an</strong>agemen<strong>to</strong>f kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;86:807–11.7. Sugita J, Kondo J. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty with completeremoval of pathological stroma for vision improvement. Br JOphthalmol 1997;81:184–8.8. Anwar M, Teichm<strong>an</strong>n KD. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty: surgicaltechniques for <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty with <strong>an</strong>dwithout baring of Descemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>e. Cornea 2002;21:374–83.9. Anwar M, Teichm<strong>an</strong>n KD. Big-bubble technique <strong>to</strong> bare Descemet’smembr<strong>an</strong>e in <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. J CataractRefract Surg 2002;28:398–403.216

Reinhart et al <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>Anterior</strong> <strong>Lamellar</strong> <strong>Kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty</strong>10. Archila EA. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty dissection of hosttissue with intr<strong>as</strong>tromal air injection. Cornea 1984-1985;3:217–8.11. Morris E, Kirw<strong>an</strong> JF, Sujatha S, Rostron CK. Corneal endothelialspecular microscopy following deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>tywith lyophilised tissue. Eye (Lond) 1998;12:619–22.12. Coombes AG, Kirw<strong>an</strong> JF, Rostron CK. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>tywith lyophilised tissue in the m<strong>an</strong>agement of kera<strong>to</strong>conus.Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:788–91.13. v<strong>an</strong> Dooren BT, Mulder PG, Nieuwendaal CP, et al. Endothelialcell density after deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty(Melles technique). Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:397–400.14. Chen W, Lin Y, Zh<strong>an</strong>g X, et al. Comparison of fresh cornealtissue versus glycerin-cryopreserved corneal tissue in deep<strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci2010;51:775–81.15. Fari<strong>as</strong> R, Barbosa L, Lima A, et al. <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior lamellartr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>t using lyophilized <strong>an</strong>d Optisol corne<strong>as</strong> in patientswith kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Cornea 2008;27:1030–6.16. Tsubota K, Kaido M, Monden Y, et al. A new surgicaltechnique for deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty with single runningsuture adjustment. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:1–8.17. P<strong>an</strong>da A, Bageshwar LM, Ray M, et al. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>tyversus penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty for corneal lesions.Cornea 1999;18:172–5.18. Shimazaki J, Shimmura S, Ishioka M, Tsubota K. R<strong>an</strong>domizedclinical trial of deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty vs penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty.Am J Ophthalmol 2002;134:159–65.19. Ardjom<strong>an</strong>d N, Hau S, McAlister JC, et al. Quality of vision<strong>an</strong>d graft thickness in deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar <strong>an</strong>d penetratingcorneal allografts. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:228–35.20. Bahar I, Kaiserm<strong>an</strong> I, Sriniv<strong>as</strong><strong>an</strong> S, et al. Comparison of threedifferent techniques of corneal tr<strong>an</strong>spl<strong>an</strong>tation for kera<strong>to</strong>conus.Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146:905–12.21. Funnell CL, Ball J, Noble BA. Comparative cohort study ofthe outcomes of deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>an</strong>d penetratingkera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty for kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:527–32.22. H<strong>an</strong> DC, Mehta JS, Por YM, et al. Comparison of outcomes oflamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>an</strong>d penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty in kera<strong>to</strong>conus.Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:744–51.23. Silva CA, Schweitzer de Oliveira E, Souza de Sena JuniorMP, Barbosa de Sousa L. Contr<strong>as</strong>t sensitivity in deep <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty versus penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Clinics(Sao Paulo) 2007;62:705–8.24. Watson SL, Ramsay A, Dart JK, et al. Comparison of deeplamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>an</strong>d penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty in patientswith kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Ophthalmology 2004;111:1676–82.25. Kaw<strong>as</strong>hima M, Kawakita T, Den S, et al. Comparison of deeplamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>an</strong>d penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty for lattice<strong>an</strong>d macular corneal dystrophies. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:304–9.26. Krumeich JH, Knülle A, Krumeich BM. <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar(DALK) vs. penetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (PKP): a clinical <strong>an</strong>dstatistical <strong>an</strong>alysis [in Germ<strong>an</strong>]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd2008;225:637–48.27. Trimarchi F, Poppi E, Klersy C, Piacentini C. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellarkera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Ophthalmologica 2001;215:389–93.28. Watson SL, Tuft SJ, Dart JK. Patterns of rejection after deeplamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Ophthalmology 2006;113:556–60.29. Feizi S, Javadi MA, Jamali H, Mirbabaee F. <strong>Deep</strong> <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty in patients with kera<strong>to</strong>conus: big-bubbletechnique. Cornea 2010;29:177–82.30. Nguyen NX, Seitz B, Martus P, et al. Long-term <strong>to</strong>picalsteroid treatment improves graft survival following normalriskpenetrating kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:318–9.31. Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Omo<strong>to</strong> M, et al. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellarkera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (DLKP) in kera<strong>to</strong>conus patients using viscoadaptiveviscoel<strong>as</strong>tics. Cornea 2005;24:178–81.32. Font<strong>an</strong>a L, Parente G, T<strong>as</strong>sinari G. Clinical outcomes afterdeep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty using the big-bubble techniquein patients with kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:117–24.33. Den S, Shimmura S, Tsubota K, Shimazaki J. Impact of theDescemet membr<strong>an</strong>e perforation on surgical outcomes afterdeep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:750–4.34. Leccisotti A. Descemet’s membr<strong>an</strong>e perforation during deep<strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty: prognosis. J Cataract RefractSurg 2007;33:825–9.35. Kaw<strong>as</strong>hima M, Kawakita T, Shimmura S, et al. Characteristicsof traumatic globe rupture after kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Ophthalmology2009;116:2072–6.36. Lee WB, Mathys KC. Traumatic wound dehiscence after deep<strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:1129–31.37. Javadi MA, Feizi S, Mirbabaee F, R<strong>as</strong>tegarpour A. Relaxingincisions combined with adjustment sutures for post-deep<strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty <strong>as</strong>tigmatism in kera<strong>to</strong>conus.Cornea 2009;28:1130–4.38. Siddiqui S, Ball J. Pressure dependent stromal oedema followingdeep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty [letter]. Br J Ophthalmol2007;91:1253–4.39. D<strong>as</strong> S, Dua N, Ramamurthy B. <strong>Deep</strong> lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty inkera<strong>to</strong>conus with healed hydrops. Cornea 2007;26:1156–7.40. Alió JL. Visual improvement after late debridement of residualstroma after <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Cornea 2008;27:871–3.41. Maurino V, All<strong>an</strong> BD, Stevens JD, Tuft SJ. Fixed dilated pupil(Urrets-Zavalia syndrome) after air/g<strong>as</strong> injection after deeplamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty for kera<strong>to</strong>conus. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:266–8.42. Min<strong>as</strong>i<strong>an</strong> M, Ayliffe W. Fixed dilated pupil following deeplamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty (Urrets-Zavalia syndrome) [letter]. Br JOphthalmol 2002;86:115–6.43. M<strong>an</strong>n<strong>an</strong> R, Jh<strong>an</strong>ji V, Sharma N, et al. Intracameral C(3)F(8)injection for Descemet membr<strong>an</strong>e detachment after phacoemulsificationin deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Cornea2007;26:636–8.44. Hong A, Caldwell MC, Kuo AN, Afshari NA. Air bubble<strong>as</strong>sociatedendothelial trauma in Descemet stripping au<strong>to</strong>matedendothelial kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:256–9.45. K<strong>an</strong>avi MR, Forout<strong>an</strong> AR, Kamel MR, et al. C<strong>an</strong>dida interfacekeratitis after deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty: clinical,microbiologic, his<strong>to</strong>pathologic, <strong>an</strong>d confocal microscopic reports.Cornea 2007;26:913–6.46. Font<strong>an</strong>a L, Parente G, Di Pede B, T<strong>as</strong>sinari G. C<strong>an</strong>didaalbic<strong>an</strong>s interface infection after deep <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty.Cornea 2007;26:883–5.47. Mohamed SR, M<strong>an</strong>na A, Amissah-Arthur K, McDonnell PJ.Non-resolving Descemet folds 2 years following deep <strong>an</strong>teriorlamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty: the impact on visual outcome. ContLens <strong>Anterior</strong> Eye 2009;32:300–2.48. Melles GR, Remeijer L, Geerards AJ, Beekhuis WH. A quicksurgical technique for deep, <strong>an</strong>terior lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>tyusing visco-dissection. Cornea 2000;19:427–32.49. Urrets Zavalia A Jr. Fixed, dilated pupil, iris atrophy <strong>an</strong>dsecondary glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1963;56:257–65.50. Patel N, Mearza A, Rostron CK, Chow J. Corneal ect<strong>as</strong>iafollowing deep lamellar kera<strong>to</strong>pl<strong>as</strong>ty [letter]. Br J Ophthalmol2003;87:799–800.217