obsessivecompulsive

Swarthmore College Bulletin (March 2002) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (March 2002) - ITS

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

it |i?ih ? ?‚4ihL hi_U_L _i @h@M*it it|@_L E}hc 4i?Lt ^i ) i?UL?|h@h tL*UL?it ?4‚ihU@t |ih@?_L tLMhi *@ **@4@_@ iU@U‚L? _i i**4@? ,t|Lc t? i4M@h}Lc it?@ tL*U‚L? ^i ?L Tih4|i _itUhMh i* ThLM*i4@ _i TL*‚>|U@ 4L?i|@h@ ^i i?uhi?|@ i* i? uLh4@ hi@*t|@ TLh^i ?L it U@T@3 _i @UL4L_@h ? ?‚4ihL t€Ui?|i _i @h@M*iti?_‚L}i?@t _i 4@?ih@ _i _@h U@M_@ @ iuiU|Lt hi3@}@_Lt L @ @h@t @h@M*it 4@UhLiUL?‚L4U@t i? uLh4@ t4*|‚@?i@ E@?^i t? __@ it ‚|* T@h@ it|_@h L|hLt ui?‚L4i?LtN?@ ti}?_@ TLtM*_@_ it t4T*€U@h *@t iU@UL?it E ) E2 T@h@ |h@?tuLh4@hi* ThLM*i4@ i? ?L *?i@*U@_h‚@|ULc UL?LU_L |@4M‚i? UL4L ThLM*i4@ _i* hi}*@_Lh*?i@* ,? T@h|U*@hc t ti UL?t_ih@ ?@ u?U‚L? _i T‚ih__@ U@_h‚@|U@ ) *@ iU@U‚L? ^i_itUhMi *@ iL*U‚L? _i *@t @h@M*it it|@_L it *?i@*c *@ tL*U‚L? ‚LT|4@ it ?@ u?U‚L?*?i@* _i *@t @h@M*it it|@_L ,t|@ u?U‚L? ti LM|i?i @ |h@‚it _i |ih@UL?it tLMhi*@ **@4@_@ iU@U‚L? 4@|hU@* _i +UU@| 2 ,t|@ t4T*€U@U‚L? tTL?i ^i *@ u?U‚L?_i T‚ih__@ it t4‚i|hU@ Qti UL?t_ih@ }@*4i?|i ?_iti@_L ?@ _it@U‚L? TLt|@UL4L ?@ ?i}@|@ hitTiU|L _i ? @*Lh 4i|@Q *L ^i UL?t||)i ?@ *4|@U‚L? LM@@* hi@*t4L ^i _itUMi i* ThLM*i4@ E}hc i* LMi|L _i Ui?|@ ULhhi?|i _i* iti? hi@*_@_ @t4‚i|hUL w@ t4T*€U@U‚L? |@4M‚i? ThL_Ui i^@*i?U@Uih|@ i? *@tL*U‚L? _i* ThLM*i4@c it _iUhc *@t tL*UL?it _i* ThLM*i4@ UL? ) t? ?Uih|_4Mhi tL?i @U|@4i?|i }@*it ,? it|i |h@M@L tTL?_hi4Lt ^i i* ThLM*i4@ it *?i@*U@_h‚@|ULc it|LU‚@t|UL ) ^i@*}?@t _i *@t @h@M*it it|@_L tL? uLh@h_*LL!?} ,t|L 4T*U@ ^i i? Th?UTL i t|i?_Lt |TLt _i tL*UL?it T@h@ i* ThLM*i4@ h4ihLc ?@ _i UL4ThL4tLc i? ^i i* UL?t_ih@ *@t @h@M*it uLh@h_*LL!?} UL4L Thi_i|ih4?@_@t )c TLh *L |@?|Lc tTL?i^i?LU@4M@?UL?tTL*‚>|U@ ,? it|i U@tL *@ @|Lh_@_ ti UL4ThL4i|i @ 4@?|i?ihi? i* Tih‚>L_L @U|@* t TL*‚>|U@ @? U@?_L *@t @h@M*it uLh@h_*LL!?} U@4Mi? UL?it@ TL*‚>|U@ ,* ti}?_L |TL _i tL*U‚L? it ?@ _tUhiUL?@*c i? ^i i* t |L4@ i?Ui?|@ t iuiU|L tLMhi *@t @h@M*it uLh@h_*LL!?} ,? it|i ti}?_L U@tL *@ u?U‚L?_i TL*‚>|U@ _iTi?_i t‚L*L _i @h@M*it it|@_L Thi_i|ih4?@_@t )c @* }@* ^i 5i?ttL?EbbHc it i* ^i it|_@4Lt i? it|i |h@M@L e5 Yhu Vdujhqw | Omxqjtylvw +4

4C S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NO L L E C T I O NJ U S TNewNC O M P E N S A T I O Nattention is being focused on Swarthmore’s lowest-paidstaff members as a result of the student-driven “LivingWage and Democracy Campaign” (LWDC) and the suggestionsmade by a staff committee set up to examine the College’scompensation system.Since fall 2000, the LWDC, composed of students and staffmembers, has issued a series of petitions and proposals to the campuscommunity. Their goal: to improve staff compensation, primarilywith the implementation of a base wage that would allow “asingle-income family to provide for its own basic needs … withoutgovernment assistance.” The salaries of an estimated 100 to 150people, mainly members of dining and environmental services,would be affected.“The living wage campaign challenges the College to live up toits stated commitment to social justice,” says Sam Blair ’02, anLWDC leader and math major with a peace and conflict studiesconcentration. “The way to do that is not only to teach about socialjustice in the classroom but also to model it in real life.”Discussions of staff compensation are not new at Swarthmore.However, the LWDC’s work, along with the 2000 hiring of MelanieYoung as associate vice president of human resources—a positionthat had been unfilled for a year—provided the momentum neededfor the College to conduct a comprehensive study of wages andrelated issues.The Staff Compensation Review Committee (CRC), formed lastspring at the request of President Alfred H. Bloom, consisted of 13staff members, including Young, with a broad range of jobs at theCollege. Among its recommendations, made last fall: a $9 per hour“Swarthmore minimum wage.” The current hiring minimum at thelowest College job grade is $6.66 per hour; the federal minimumwage is now $5.35.Other recommendations included the following:• Eliminating mandatory employee contributions to the College’spension plan and increasing the College’s contribution from7.5% to 10%• Decreasing the cost gap between single and family healthinsurance by freezing the benefit bank (the pretax expense accountoffered with College employee benefits) at current levels and shiftingnew funds to support family coverage• Increasing funds available for tuition reimbursement for staffmembers taking courses for personal or professional development• Establishing longevity awards in the amount of $100 per yearfor staff members at 5-year anniversaries of their employment atthe CollegeAccording to Young, the overall compensation goal for Collegestaff should be comparable with that of the faculty. “That is,THE COLLEGE’S LOWEST-PAID WORKERS WOULD RECEIVE A RAISE TO$9 PER HOUR UNDER A PROPOSAL FOR A “SWARTHMORE MINIMUM WAGE”MADE BY A STAFF COMMITTEE THAT REVIEWED COMPENSATION. LIVINGWAGE ACTIVISTS DON’T THINK THE PLAN GOES FAR ENOUGH.JIM GRAHAMSwarthmore should have a salary and benefit plan that is slightlybetter than the average of market comparison groups,” she says.Young explains that the College regularly compares its numerousjob classifications with both local and national benchmarks andhas spent considerable new funds in recent years to bring staffcompensation up to competitive levels.“I thought two things going into this process: It must be inclusive,and it must be grounded in the facts,” Young says. “So weworked hard to have a committee that was inclusive of lots of viewpointsand that studied a shared set of facts, not just opinions.”Although filled with strong opinions, the debate over staff compensationat Swarthmore has been largely civil and unmarked byhostility—unlike at Harvard University, where, last spring, studentactivists made national headlines by staging a successful threeweeksit-in. That is no accident.“We’re very concerned about not alienating anyone,” says KaeKalwaic, an LWDC leader and administrative assistant in the Educationprogram. “People can come on board softly, without harshconfrontation.”For Kalwaic, who has worked on these issues for seven of hernine years at the College, a living wage and other workers’ rightsare human rights issues. “We feel that you can’t run an institutionwith resources and a huge endowment and not pay people a livingwage,” she says. “If the administration wanted to find the moneyand live up to the College’s commitment to social justice, that’swhat they’d do.”

6C S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NO L L E C T I O NJIM GRAHAMH o u s i n gc r u n c hAsharp drop in the number of students studying abroad thisspring—combined with a larger than usual number returningfrom fall foreign study—caused a scramble for student housing.So many students signed up at the December housing lottery,looking for rooms for the spring semester, that the College wasforced to exercise what Myrt Westphal, director of residential life,calls “the overflow option.”“Before each school year begins, we always hold 400 beds, 375 ofwhich are taken by freshmen. The remaining 25 are shifted to thewaiting list, which usually consists of sophomores,” Westphal says.“If the new class—or overall enrollment—is larger than expected,we go to the overflow option. This spring, the overflow mainly consistsof juniors returning from foreign study.”Students with low lottery numbers had to select rooms in theStrath Haven Condominiums, on the corner of Yale and Harvardavenues—rooms usually reserved for visiting professors and guestsof the College.Strath Haven was first used for overflow student housing duringthe 1996–97 academic year when the classes of 1997 and 2000—two of the largest in College history—pushed the student populationto a record high. But no students have lived there for a year anda half, Westphal says. This spring, however, there are about 1,375students studying on campus, out of a total tuition-paying studentbody of 1,432, which includes students on exchange programs orstudying abroad.“Our class sizes have stablized now,” Westphal says, “but havingenough housing still depends on 7 to 8 percent of students livingoff campus or being on leave.” That percentage dropped this semester,mainly because only 57 students are studying abroad, comparedwith the average 85 to 90 of recent spring semesters. Westphalattributes the decline to “students choosing not to go abroad”THIS IS DEFINITELY A CUT ABOVE THE AVERAGE DORM,” SAYS BRIANBYRNES ’02 OF HIS SPRING-SEMESTER ROOM AT THE STRATH HAVEN CON-DOMINIUMS. BYRNES, WHO IS RESIDENT ASSISTANT FOR STUDENTS IN THE“OVERFLOW” RESIDENCE HALL, RETURNED TO SWARTHMORE AFTER ANEXCHANGE SEMESTER AT POMONA COLLEGE LAST FALL, WHERE HE PLAYEDFOOTBALL.because of world conditions” but adds that no students have spokento her about this particular concern. “We’re not alone in this,”she adds. “My counterpart at Haverford is having the same problem.”Foreign Study Adviser Steve Piker says he is not convinced thatrecent events caused the decline. “The number is certainly downsignificantly from last spring,” he says, “but we don’t know that it’sdue to the crises.” He points out that the total number of Swarthmorestudents studying abroad this academic year is 151, which isnormal. “The difference is that 94 students studied abroad in thefall compared with an average of 65,” he explains. “There is alwaysan imbalance between semesters, but I can’t remember it not beingin the other direction.”“I don’t think any student mentioned the crises to me in talkingabout foreign study,” he adds. “Of course, the students who come into talk to me are those who want to study abroad. There is a goodpossibility that I didn’t speak to those who chose not to for that reason.”One factor in the large number of students choosing to studyabroad last fall may be a change in College regulations allowingfirst-semester seniors to participate in foreign study for the firsttime; 12 seniors studied abroad last fall. Whether some juniorsdecided to take advantage of the new rule and delay foreign study tofall 2002 or opt out altogether will not become evident until studentsbegin to apply for fall programs.—Cathleen McCarthy

M u l t i f a i t h t r i b u t eWe have much healing to do, and wegather tonight to do that and tomourn those lost. We lost alumni, we lostfamily, and we lost dear friends,” PaulineAllen, Protestant adviser, tolda somber group gatheredin Lang ConcertHall on Dec.11, for a memorialservice threemonths afterthe terroristattacks.“On Sept. 10, ifsomeone had told uswhat would happen thenext day, we would havedismissed it as a fair pieceof science fiction—or as a bad dream. Yet ithappened,” said President Alfred H. Bloom,who witnessed the World Trade Centerattack with his wife, Peggi.Students, staff, and faculty members readfrom the Buddhist, Hindu, Quaker, andMuslim traditions and offered hymns andsongs from the Jewish, Catholic, and Bahá’ífaiths. Music expressed the emotions of theoccasion, from the drama of Fauré’s“Requiem,” sung by the College chorus, tothe comforting familiarity of “AmazingSTEVEN GOLDBLATTʼ67PROTESTANT ADVISER PAULINE ALLENGrace,” offered by the student a cappellagroup Sixteen Feet.Two students from New York City sharedtheir thoughts, including Katherine Bridges’05 who read a touching poemshe had written abouther brother-in-law, afirefighter whodied on Sept. 11.Faruq Siddiqui,professor ofengineering, readwith feeling fromthe Quran: “Whosoeverkilleth a humanbeing … it shall be as ifhe had killed all mankind,and whosoeversaveth the life of one, it shall be as if he hadsaved the life of all mankind.”Siddiqui, a Muslim, then added his ownwords: “Muslims all over this country haveprayed to Allah for healing the woundsopened up by this monstrous act, for bringingthe people of this country together, forletting the better angels of our nature takeover our thoughts and deeds so that we may,as people of various faiths and beliefs, makethis world a better and safer place to live in.”—Cathleen McCarthyUser-friendly signsThanks to recently designed andinstalled signs, visitors to theCollege are finding it easier to navigatetheir way around these days.“There was an old-style attitude thatif you don’t know your way aroundthe campus, you don’t belong here,”says Janet Semler, director of planningand construction for FacilitiesManagement, who has overseen thesign project since it began in January2000. “But more than 20,000 peoplevisit this campus each year, most ofwhom are not part of our Collegecommunity. We want to welcome thesevisitors by making the campus moreuser friendly.”JIM GRAHAMIn Memoriam: Bonnie Brown Harvey ’54Bonnie Harvey, former assistant tothe health science adviser, died onNov. 17. Harvey worked at the Collegefor 24 years, helping countless studentsnavigate the medical schoolapplication process, before retiring in1996. Professor Emerita of BiologyBarbara Yost Stewart ’54, who servedas health science adviser from 1985 to1996, said of her friend and classmate,“She knew every student byname and shared their ups, theirdowns, their joys, and their woes.”Although the acceptance rate for Swarthmore students and alumniapplying to medical school is twice the national average, inevitablysome applicants are rejected. It was with these students, said Stewart,that “Bonnie was at her best. She was so sympathetic andcompassionate. She commiserated with them but also tenderlyencouraged them to go on with their lives.”New Alumni ManagersThe Board of Managers elected three new members at its Decembermeeting: Cynthia Graae ’62 and Bennett Lorber ’64 are AlumniManagers, and Tanisha Little ’97 is a Young Alumni Manager. Theywill serve four-year terms.Graae is a Washington, D.C., freelance writer with a lengthypublic service career, working mainly on civil rights issues. Lorber isThomas M. Durant Professor of Medicine and chief of the Sectionof Infectious Diseases at the Temple University School of Medicineand Hospital. Little is a corporate law attorney for Stroock , Stroock& Lavan in New York.CYNTHIA GRAAE ’62 BENNETT LORBER ’64 TANISHA LITTLE ’97M A R C H 2 0 0 27

C O L L E C -S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NW i n n i n gPHOTOGRAPHS BY JIM GRAHAMc o m b i n a t i o nTOP SCORERS HEATHER KILE ’02 (TOP LEFT) AND KATIE ROBINSON ’04 (TOP RIGHT) LEDTHE WOMEN’S BASKETBALL TEAM TO A 20–7 RECORD AND THE CONFERENCE FINALS.Swarthmore women’s basketball hasattracted many fans in the past coupleof years. Lately, they’ve been coming towatch Heather Kile and Katie Robinson viefor points. Kile, a senior forward, set newstandards for the team from the very beginningof her Swarthmore career, leading herteammates to three Centennial Conferenceplay-offs, including a run for the championshipin this year’s final game againstWestern Maryland.After defeating Franklin & Marshall61–56 in the semifinal game, Swarthmorecould not get its offense moving and managedonly 12 points in the first half againstWestern Maryland and lost 66–38. Theteam’s season record was 20–7 overall and12–3 in conference play.Kile was named Centennial ConferencePlayer of the Year in 2000 and was the firstwoman in conference history to be namedFirst Team All-Conference for four years. InJanuary, Kile broke the College’s scoringrecord, finishing the regular season with acareer total of 1,921 points.This year, Kile shared the spotlight withsophomore guard Robinson, who earnedfour conference Player of the Week honorsand was later named Centennial Player ofthe Year. On Feb. 6, she scored a schoolrecord40 points in an 85–82 double overtimevictory over Johns Hopkins.“She and Heather both had an amazingseason,” says Adrienne Shibles, assistantprofessor of physical education and headcoach of women’s basketball. Robinson ledSwarthmore to the Seven Sisters Tournamentchampionship with 29-point gamesagainst Vassar and Wellesley and 18rebounds against Vassar. She was namedoutstanding defensive player of the tournamentand earned All-Tournament honors.“Heather is probably the best basketballplayer ever to come through Swarthmore.We will really miss her next year. Katie is acrowd favorite. She’s so fun to watch,” saysShibles. “These women have come to expectto win—which is nice. They’re confident,and they play well together.”—Cathleen McCarthy8

C L O T H I E R F I E L D S T O B E M O D E R N I Z E DGoal posts are conspicuously absentfrom Clothier Fields these days.Football games and practices havegiven way to soccer, lacrosse, field hockey,and intramural sports.Now the College’s stadium field is aboutto undergo more dramatic changes. At theirFebruary meeting, the Board of Managersapproved a $2 million plan to upgradeClothier Fields, including adding lightingand artificial turf and resurfacing the outdoortrack.Lighting the field will extend the hoursfor outdoor sports. “The ability to practicein the evenings should lessen conflicts withacademic demands, especially for intramuralteams,” says Adam Hertz, associatedirector of intercollegiate athletics.Artificial turf is also expected to increaseoutdoor play by extending the season itself.“In early spring, our teams are normallyforced to go indoors because of bad weatheror wet conditions,” Hertz says. “With artificialturf, if there’s snow on the ground, youJIM GRAHAMAFTER CLOTHIER FIELDS RECEIVE THEIR NEWARTIFICIAL TURF, SNOW CAN BE SHOVELED OFF,ALLOWING ATHLETES TO PRACTICE YEAR-ROUND.can shovel it off and start playing. Turf alsomaintains its quality through summerdroughts.”The technology of artificial turf hasimproved substantially in recent years,Hertz says. “It’s not like the old Astro Turf,which was like green carpet. Many think it’sbetter than natural grass now. Artificial turfdoesn’t rut or develop bare spots, which cancause injuries,” he says. That durability hasan economic advantage as well, says LarrySchall ’75, vice president for Facilities andServices. “If you’re on a grass field toomuch, you ruin it,” Schall says. “This youcan’t ruin.”Combined with recent improvements toindoor athletics facilities, the Clothier Fieldsproject will give the College “a showplaceathletics complex,” Hertz says. “We hopethese changes will not only improve facilitiesfor our current athletes but attract newones as well.”—Cathleen McCarthyIn other winter sports ...Women’s swimming (9–2, 5–2) captured itssecond consecutive Centennial ConferenceChampionship, outdistancing runner-up Gettysburg,707–604.5. Three relay teams andthree individuals provisionally qualified forthe NCAA Championships. The Garnet closedthe conference meet on a high note, as the400 freestyle relay team of Melanie Johncilla’05, Amy Auerbach ’02, Davita Burkhead-Weiner ’03, and Natalie Briones ’03 won in ameet with a school-record time of 3:37.68.The 800 freestyle relay team of Johncilla,Katherine Reid ’05, Burkhead-Weiner, andAuerbach were victorious in a school-recordtime of 7:55.78. Briones and Burkhead-Weiner teamed with Kathryn Stauffer ’05and Leah Davis ‘04 to win the 200 freestylerelay in a school-record time of 1:39.16.Broines came home from the three-day meetwith team-high of six medals.Men’s swimming (5–4, 3–3) set threeschool records en route to a fourth-placefinish at the Centennial Championships.Mike Dudley ’03 won the 200 individualmedley in 1:56.28. John Lillvis ’03 capturedthe 400 individual medley in 4:11.49. Thisduo teamed up with Jacob Ross ’05 andMike Auerbach ’05 to set a school record inthe 200 freestyle relay with a third-placefinish of 1:28.24.In women’s indoor track, Imo Akpan ’02won six gold medals at the Centennial ConferenceIndoor Track and Field Championshipsto earn Outstanding Female Athleteof the Meet honors. Akpan won the 55-meter dash in a school-record time of 7.20seconds, which automatically qualified herfor a trip to the NCAA Division III Championships.She set school and meet records inthe long jump with a leap of 18’0.5”. Akpanalso won the 200-meter dash with a school,conference, and meet-record time of 25.51and crossed the line first in the 400-meterdash in a meet-record time of 58.34. Earlierthis season, Akpan set the school record inthe 400 with time of 57.4. Akpan alsoteamed with Njideka Akunyili ’04, ElizabethGardner ’05, and Claire Hoverman ’03 tocapture gold in the 1,600-meter relay andthe distance medley relay. The 4 x 400 relayteam set a school record of 4:07.60, and thedistance team set a school and meet recordwith a time of 12:37.97. Sarah Kate Selling’03 broke her school record in the pole vaultby clearing the 7-foot mark at a meet earlierin the season.The badminton team captured its first-everNortheastern Collegiate Tournament Championship.Karen Lange ’02 was the women’ssingles champion, and Brendan Karch ’02captured the men’s title. Karch teamed upwith Chris Ang ’04 to win the men’s doublestitle, and Ang paired up with Olga Rostapshova’02 to win the mixed-doubles championship.In men’s basketball (6–19, 2–11), JacobLetendre ’04 set the school record with 44steals this season, and he ranks fifth on thecareer list with 84 steals. Matt Gustafson’05 led the Garnet in scoring, averaging14.2 points per game. Gustafson’s 55 threepointersrank him third on Swarthmore’s single-seasonlist.—Mark DuzenskiM A R C H 2 0 0 29

ideas. For the next hour, Smulyan leads her students through variousaspects of Skinner’s views on learning. Lecture blends with discussionas she encourages students to think about how they haveseen his theory applied, both in their own educational experiencesand in the classrooms where they are observing as part of thecourse’s required field placement.Soon it becomes clear that the students are skeptical of Skinner.Although Smulyan occasionally plays devil’s advocate, pointing outways in which aspects of Skinner’s work might beuseful for teachers, the students question Skinner’srote, step-by-step method of learning, whichthey say stifles creativity, fails to allow for differentlearning styles, and does not promote anunderstanding of the concepts that underlie aparticular skill.Still, the students have no trouble recognizingthat Skinner is describing the real world of education.One student saw Skinner’s ideas reflected ina Chester kindergarten classroom, where children are learning toread in incremental, mechanical steps. Another student recalls helpinga child with a math worksheet that broke down fraction writinginto a sequential series of more basic skills.Providing students with a grounding in theory and an opportunityto observe in Philadelphia-area schools, Smulyan’s introductorycourse is in many ways representative of the entire Educationprogram at Swarthmore, which aims above all “to help studentslearn to think critically about the process of education and the placeof education in society,” according to program literature.When most people think of Swarthmore, the Education programis not what first comes to mind. Although in 1996–97, the thirdSwarthmore’s Educationprogram approaches its subject asa field of inquiry, not a career.highest number of bachelor’s degrees awarded nationally went toeducation majors, and, at the graduate level, there were more master’sdegrees in education than in any other discipline, educatingteachers has traditionally been regarded as the province of largeM A R C H 2 0 0 211

CREDITS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I Nuniversities and teachers’ colleges, not liberalarts institutions such as Swarthmore.Although Swarthmore’s program may besmall—with three tenured faculty members,one additional full-time professor, and generallyone or two part-time adjuncts—oneout of three Swarthmore students takesIntroduction to Education sometime duringhis or her undergraduate career, and severalhundred students enroll in one of the other15 or so education courses and seminarsoffered each year.As a result, many Swarthmore studentswho had not considered teaching discovereducation at the College. According to Professorand Program Director Eva Travers,only three or four incoming students peryear express interest in the program on theirapplications. “But I think Intro to Educationhas such a good reputation that people hear about it, take it,and get interested in education,” she says. She described it as a “polished”course that over the years has remained similar in terms ofstructure and core readings. Focusing on teaching and learning duringthe first half of the semester and education and society duringthe second, the course “has its own kind of energy.”Allison Young ’87, now an assistant professor of education atWestern Michigan University, recalls that she “pretty much stumbledinto the education program” at Swarthmore. During the springsemester of her sophomore year, she needed a fourth credit anddecided to take Intro to Education because it fit into her schedule.“For the first time in my Swarthmore experience, I felt like I actuallyknew some things and that I had something to say in class,” shesays. “I had Eva Travers for that course, and it kicked my butt in a lotof good ways.”For Thomas Crochunis ’81, Intro to Education deepened an existinginterest in the field. Crochunis earned a degree in English withteaching certification, went on to teach first high school English andthen college writing and literature courses before entering the fieldof education research publishing. Although interested in educationin high school, he became “engaged” in the field after taking Intro toEducation and teaching physical education during his field placementat a school for children with special needs. “That hooked me,”he says.Like many aspects of Swarthmore, the study of education islinked to the College’s Quaker roots. In An Informal History ofSwarthmore College, Richard Walton writes that part of the foundingmission of the College was to train Quaker teachers for elementaryand secondary schools. Friends such as Martha Tyson, one of theCollege’s founders, feared that Quakers would assimilate into thelarger culture if their children were not educated by teachers whoshared the values of the Society of Friends.12

The study of education is informed byother disciplines in the liberal arts.Then, in 1969, a change in Pennsylvania law made it possible forsmall, liberal arts institutions like Swarthmore to award teachingcertification. Previously, only large universities and specializedteacher training programs could offer the range of courses neededfor certification.Swarthmore’s program expanded in the 1970s with the arrival ofTravers, who specializes in educational policy and urban education,and Bob Gross ’62, now dean of the College. Joining the program inthe 1980s were Ann Renninger, with a specialty in educational psychology,and Smulyan, a 1976 graduate of Swarthmore whoseexpertise is in social and cultural perspectives on education. DianeAnderson, now a full-time nontenure-track professor, specializes inliteracy and is also the faculty adviser for Learning for Life, a volunteerprogram that encourages students to work with staff memberson topics such as literacy and computer skills. In addition, adjunctfaculty members teach two or three electives each year, includingEnvironmental Education, Counseling, and Special Education.Despite this growth, the study of education at SwarthmoreCATHY DUNN ’93 (ABOVE) TEACHESENGLISH AT STRATH HAVEN MIDDLESCHOOL IN WALLINGFORD, PA.SHE RECEIVED “HUGE AMOUNTSOF HELP,” SHE SAYS, FROM HERSWARTHMORE EDUCATIONPROFESSORS DURING HER FIRSTFEW YEARS OF TEACHING: “ACOUPLE OF SUNDAYS A MONTH,ANOTHER NEW SWARTHMORETEACHER AND I WOULD STOP ATEVA TRAVERS’ HOUSE FOR DINNERAND HELP WITH OUR CLASSES.”PHOTOGRAPHS BY GEORGE WIDMANAlthough Swarthmore dropped education courses from its curriculumin the 1930s, the program was revived in the 1950s by thelate Alice Brodhead, a Friend and the former head of a Quakerschool. Brodhead became the first director of the new Educationprogram at Swarthmore; she and one other professor were the onlyfaculty in the program until the early 1970s.remains within a program rather than a department. Students cannotmajor solely in education. Travers says the reason is primarilyphilosophical. “We think that education informed by another disciplineis a more effective way of thinking about education,” she says,“especially at the undergraduate level.”Gross, who taught in the program for six years before leaving theM A R C H 2 0 0 213

MELANIE HUMBLE ’86 (LEFT)TEACHES ENGLISH AND DRAMA ATCARABELLE HIGH SCHOOL IN RURALCARABELLE, FLA., WHERE SHE HASBEEN HONORED TWICE ASTEACHER OF THE YEAR. HUMBLESAYS THAT THE APPROACH TOWARDTEACHING THAT SHE LEARNED ATSWARTHMORE HAS PLAYED AGREATER ROLE IN HER SUCCESSTHAN ANY SPECIFIC SKILL.S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I N14College from 1983–89, expressed a similarsentiment. “I’m not keen on a major in education,”he says. “I would argue there’s apower and relevance in connecting [thestudy of] education with the rest of a student’seducational program.” The study ofeducation “forces students to go further,”says Gross. “They must become self-consciouslearners—more effective learnersacross the board.”In this regard, Swarthmore is similar toother institutions belonging to The Consortiumfor Excellence in Teacher Education,which was founded in 1983 and whose 20members are selective, private liberal artsinstitutions in the Northeast. Unlike manyuniversities and teachers’ colleges, consortiummembers generally do not offer educationas a major; instead, work in educationis integrated into the broader liberal artscurriculum.But Swarthmore differs from most consortium schools in thatteacher certification is not the primary or sole focus of its educationprogram, according to Travers. Instead, the College offers morebroad-based studies in educational theory, policy, and practice. Studentsmay develop a special major that combines education and asecond discipline—an option that involves a culminating exercise,such as a thesis, that brings together both areas of study.Still, an important component of Swarthmore’s education programis teacher certification, which requires practice teaching. Forhalf a semester, students teach full time, develop lesson plans, andassess curricula. According to Travers, supervised practice teachingenables them to “have a much more effective beginning teachingexperience…. Teaching is not all intuitive; some teachers can bemade much better. Knowing the discipline is necessary, but it is notsufficient, especially in elementary and secondary schools with studentsfrom a variety of backgrounds.”Travers says, in a typical year, the Education program generallyhas 20 to 25 special majors, 6 to 8 Honors students, and 12 to 16student teachers seeking certification. Most Swarthmore educationstudents earn certification in social studies or English; a few get certifiedin science and math and occasionally in a foreign language.Approximately one-quarter of students earning certification do so inelementary education through a joint program with Eastern College.Recently, Travers says she has seen increased student interest inthe Education program. The number of special majors has risenin the past 10 years, though it is difficult to make comparisons with

the early years of the program, when certification was the maingoal for students. Moreover, changes made in the Honors programfive years ago have allowed students pursuing Honorsmajors in other disciplines to incorporate a minor in educationinto their programs.Education courses tend to attract a fairly diverse group of students.According to Travers, the percentage of students of color inStudents who receive teacher certificationgraduate with excellent job opportunities.education classes is at least as high as that in the College as awhole, where about a third of the student body is nonwhite. Yetjust as women teachers continue to outnumber men in elementaryand secondary education, the ratio of women to men in mostof Swarthmore’s education classes is generally two to one.Students who receive certification graduate with excellent jobopportunities, Travers says. In recent years, all who wanted toteach, no matter the subject, have been successful in finding jobsimmediately after completing the program.Although the study of education often leads to a job teaching inan elementary or secondary school, this is not always—or even predominantly—thecase for Swarthmore alumni. Many students takeeducation courses with an eye toward a broad range of careers andlife experiences, from public policy to parenting.Gil Rosenberg ’00, a math major who earned teaching certification,is currently a graduate student in math and a teaching assistant.Rosenberg highly recommends undergraduate work in educationfor students who intend to become teaching assistants ingraduate school and then professors at a college or university.“There is little official educational training for these positions,” hesays, “so having some theory and practice really goes a long way. I’msure we’ve all had professors who we wished had taken an educationcourse or two at Swarthmore.”Barbara Klock ’86, a psychology major who received certificationin elementary education, taught at Swarthmore’s elementary schoolfor several years before going to medical school. Now, as a pediatrician,Klock says she finds herself teaching “every day.”Those who do choose the elementary or secondary school classroomhave all felt the widespread attitude that teachers are undervaluedby society. But, says Kate Vivalo ’01, who graduated with aspecial major in sociology/anthropology and education, “Swarthmorestudents and students of that caliber are exactly who you wantin a classroom.”Vivalo experienced firsthand prevalent attitudes toward teachingwhen she returned to her hometown recently. People asked abouther plans for the future, and their response was: “‘You’re just goingPHOTOGRAPHS BY RAY STANYARDM A R C H 2 0 0 215

S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NOvercoming the “EndemicUncertainties”of TeachingBy Lisa Smulyan ’76Professor of EducationMy first few months of teaching seventh grade inBrookline, Mass., were not a huge success. Classroomdiscipline did not come naturally to me, and my studentshad to learn that they could respect a teacher who wassmall, female, and not terribly loud. By January, I was no longer indanger of being fired and even had days I enjoyed. Then, a fewmonths later, I got a note from the mother of one of my students.It said:I was going to send you a note today to tell you about“Babies and Banners” a propos of the article you gave outon women and unions. Then Daniel comes home to tellme you showed them the movie! How wonderful! I justcan’t tell you how much it means to me to have Danielexposed to such an imaginative, perceptive, and kindteacher.That day, I realized that my fellow teachers and I were rarelyrecognized for what we did. Teachers at all levels teach becausethey think it is important work—work that can make a difference.But, given that our students keep moving on, we don’t often seethe fruits of that labor. Dan Lortie, in his classic sociological studySchoolteacher describes the “endemic uncertainties” of teachingthat lead to few tangible rewards.STEVEN GOLDBLATT ʼ67On Oct. 26–27, Swarthmore hosted a conference called Reflectionson Education and Social Justice: A Celebration of the Programin Education. Four Swarthmore alumni (Jack Dougherty ’87,Esther Oey ’87, Betsy Swan ’86, and Allison Young ’87) plannedand organized the conference with the help of the Alumni Officeand the Education program faculty and staff. More than 200Swarthmore alumni involved in education, current students andfaculty, and local educators gathered to discuss issues of importancein the field and to reflect on the ways in which Swarthmorehas influenced their work. It was a truly amazing event, one thatswept away those endemic uncertainties and left us all feelingrewarded, inspired, and appreciated.The conference began with a keynote address on Friday nightby Herbert Kohl, whose book 36 Children has been central to theIntroduction to Education syllabus for a generation of Swarthmorestudents. The conference included a full day of concurrentsessions on Standards and Student Assessment, Urban Schooling,Mindful Technology, Reaching Adolescents Outside of theTraditional Classroom, Special Education, Social Justice in theClassroom, and others. In a session on Educators’ Responses toSept. 11, three alumni led a discussion of questions that rangedfrom how the content of classrooms may change to how we constructand teach about notions of conflict and social justice. Inanother session called The Practical Life of Teaching—and Howto Balance It With the Rest of Your Life, presenters and sessionparticipants talked about how to maintain our intense commitmentto teaching without sacrificing other aspects of our lives.“How,” one participant asked, “can you go on a date when youalways fall asleep at 9 p.m.?” The conference closed at the FriendsMeetinghouse with a collection dedicated to Swarthmore’s Educationprogram.An incredible energy, all focused around education, emergedfrom this conference. We have materials and bibliographies andphone numbers of like-minded people who we know share ourconcerns and interests. We have alumni interested in sponsoringanother conference in five years.The conference demonstrated that Swarthmore graduates, inteaching and the other fields represented at the conference, areleaders in their communities; although they, like most educators,sometimes struggle to see where they are making a difference.Many of the conference participants talked about how the excitement,the commitment, the “spark” they want in their work hadbeen renewed through the presentations and the informal interactionsat the conference. They also recognized the role of the College’sEducation program in initiating, nurturing, and continuingto support that spark.When I got that letter from Daniel’s mom 24 years ago, I starteda file labeled “Kudos.” The conference program will go in there.I haven’t felt so rewarded in years.16

to teach? You had so much potential,’” says Vivalo, who is nowworking for Youth, Inc., a Washington, D.C., consulting firm thatprovides event planning and management services to nonprofitorganizations that serve the needs of children.For some students who choose not to teach, one issue is the relativelylow pay teachers receive versus the high cost of education atschools like Swarthmore. Allison Young says that when she calledhome from college to tell her parents—who were teachers themselves—thatshe planned toearn her teaching certificationin social studies, herfather hung up on her. “Hereally didn’t want me to be ateacher, and he was prettyangry,” she says. “I wondernow if the issue was aboutthe financial stuff—going toSwarthmore to become a teacher is an expensive proposition,whereas most states have a couple of local universities that dealmostly with teacher education.” But while saying she “understandshis response much more now,” Young also says she learned thingsat Swarthmore that could not have been duplicated at a state university.Many students and alumni also say that education fits intotheir liberal arts curriculum because of the way it is taught atSwarthmore.“I see it as a discipline,” says Eve Manz ’01, a psychology andeducation special major who is now student teaching in Philadelphia.“The department teaches education not as a career but as afield of inquiry.”“It’s a much more intrinsic perspective on education,” Youngsays, “studying education for the sake of studying it and maybehaving ideas about how to make it better.” Even the certificationprocess uses the metaphor of “‘teacher as thinker’ as opposed to‘teacher as technician,’” Young added. “This is so powerful becausein the teacher-thinker model, you keep learning.”The interdisciplinary nature of education at Swarthmore bringstogether many different disciplines in the social sciences and evenhumanities. About a third of the education courses listed in theCollege catalog are cross-listed with other departments. In addition,the program provides an opportunity to combine theory andpractice because most education courses include a field placement,which may involve observing, tutoring, teaching, or research.“This is where the theory is lived,” Gross says. “It functions inthe way that a lab in science does. How do you know how the theoryworks unless you see kids struggling with it and preferably strugglealong with the kids?”Now an assistant professor of education at Trinity College, JackDougherty ’87 majored in philosophy and earned teaching certificationin social studies. “Sometimes I felt like a misfit at Swarthmore,”Dougherty says. “The book learning seemed so distant fromthe reality learning, and I felt that the world didn’t make senseunless I could merge the two, and that wasn’t happening in myterm papers and blue-book exams.” Dougherty saw Intro to Education,with its “combination of academics and participant-observationin schools,” as a course in which this synthesis could occur.But the study of education is also integral to the liberal arts curriculum,according to those interviewed, because it allows studentsto reflect on their own education and to learn about the educationalexperiences of others. Although easy to take for granted, students’educational experiences have played a significant role intheir lives for the past 15 years, shaping who they are and their outlookon the world.“At the end of the day, Swarthmore gave me thetools to do a job that seems significant to me.”Chela Delgado ’03, an Honors history major and educationminor, says, “You’re able to look back at your experience and compare/contrastthat with what you’re actually learning in terms oftheory.”Education courses have also enabled students to examine theirmore recent experiences in Swarthmore classes. Nicole Bouttenot’01, a math and education special major, says she had “a bad experiencewith the math department at Swarthmore,” and her educationclasses helped her understand why she struggled in some mathclasses.There is not even a stoplight in the rural Florida town whereMelanie Phillpot Humble ’86 has taught for much of hercareer. “The kids I teach will probably not get the chance to go to aSwarthmore,” says Humble, who majored in English and earnedteacher certification. “I can bring a little bit of it to them. I canbring those great books, those great professors, the lessons Ilearned from my peers, the critical thinking to them. It seems aserious responsibility of elite colleges and universities to spread theintellectual wealth that way.”Humble says she has been teacher of the year both on theschool and county level and believes these accomplishments are “adirect result of the preparation I got from Eva and Lisa.”The approach she learned toward teaching has played a greaterrole than any specific skill, Humble says.“You must be willing to look at [teaching] from many differentperspectives, to analyze and think creatively,” she says. “You mustbe willing to collaborate but also to challenge the status quo. Youmust be willing to see that the process is the product. And what Ilearned about teaching is that it is worth doing.”Pointing to the difficulties of teaching, such as the low pay andconstant criticisms from government officials, Humble says, “I’mnot a Pollyanna about education, far from it—but, at the end of theday, Swarthmore gave me the tools to do a job that seems significantto me.” TSonia Scherr is a reporter with The Valley News in Norwich, Vt. Thisarticle first appeared in The Phoenix (March 1, 2001) and is reprintedwith permission.M A R C H 2 0 0 217

FamiliesStrongas OaksELEFTHERIOS KOSTANS/COURTESY OF THE SCOTT ARBORETUMS W A R T H M O R E ’ S L O R E B R A N C H E S T H R O U G H T H E G E N E R A T I O N S .By Andrea HammerS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NLike the intertwining oak branches forming an archway over Magill Walk, the latticeworkof multigenerational families at Swarthmore fans out from a solid trunk of family and College history.These interwoven offshoots of relatives within the larger College family remain rooted in pastmemories while stimulating further growth at Swarthmore.According to Jim Bock ’90, dean of admissions and financial aid, “legacies are typically admitted at aslightly higher rate than other students in the applicant pool, and they also tend to be a bit strongeracademically.” The “strongest preference" is given to applicants with parents or siblings who are alumni,he says. Although “every consideration is given to legacies, it doesn’t necessarily make or breaka decision," which is based on many student skills and interests.As one current student from a multigenerational family says, “I rarely run into peoplewho know other members of my family, and I prefer to be known for who I am, not just who I’m related to."But Bock’s experience is that students with “legacy ties have a good sense of Swarthmore thatis transferred to the student and a common bond of intellectual passion and a love of learning."Although changing times have shaped individual experiences for each generation, the insights ofthe following three Swarthmore families—representative of the 117 with three or more generations—openwindows on the essence of Swarthmore that endures, along with the age-old oaks first planted in 1881.18

Jared Thompson ’05, the fourth consecutivegeneration on his father’s side toattend Swarthmore, mined his family’s richhistory during the winter holidays. Beforetraveling from his West Hartford, Conn.,home to visit grandmother Jean MaguireThompson Seely ’40 and aunt MarjorieThompson Mogabgab ’74 in Nashville,Tenn., Jared described maternal grandparentsEdmund ’39 and Adalyn Purdy Jones’40 as “loyal members of the SwarthmoreCollege community." He also mentionedcousin Guian McKee ’92 and carriedthoughts of now-deceased great-grandmotherMarjorie Gideon Maguire ’14,whose spirit still guides his family’s story.When Jared asked grandmother Jeanwhy she attended, she said: “Well, Motherhad a whale of a good time at Swarthmore,and that certainly influenced it. I also knewit was intellectually a top college."In turn, Marjorie was similarly influencedby her grandmother’s and mother’smemories. “My grandmother told wonderfulstories about her life at Swarthmore thathave been part of family lore for several generations,"she said. “They were mostly aboutboyfriends and clever circumventions ofParrish house mothers."Also encouraged by Jean’s experience,shaped as a swim team and Outing Clubmember, Marjorie’s college choice was complicatedby having spent grades 4 to 12 inSwarthmore. “I wanted to attend collegesomewhere other than my hometown, to‘expand my horizons’ and establish independencefrom home. However, I was wellaware that Swarthmore was the cream of thefive excellent colleges I had applied to; whena fine scholarship offer was made, I had nofurther hesitation," she said.Family stories also convinced Jared aboutthe benefits of choosing a small liberal artscollege. “I was more influenced by my ownexperiences visiting Swarthmore than by thestories I have heard from relatives," he said.“However, hearing how much they all enjoyedbeing at Swarthmore was certainly anotherfactor that made the College appealing."Jean told her grandson, “Mother knewmy friends, and they all really liked her. Theyeven had a pet name for her," Chappie, createdafter she chaperoned a shore trip. “I knewsome of Marjorie’s friends," she added. “Thereis a common bond that comes from knowingthe friends of different generations."“We can still surpriseeach other with untoldstories.”ABOVE: JARED (RIGHT) MINED HIS FAMILY’SSWARTHMORE HISTORY WITH HIS AUNT MARJORIE(CENTER) AND GRANDMOTHER JEAN (LEFT).BELOW: “IT WAS FUN TO GO TO REUNIONS WITHCHAPPIE,” SAID JEAN (CENTER) ABOUT HERMOTHER (LEFT), ATTENDING THE 1984 REUNIONWITH DAUGHTER MARJORIE (RIGHT), “AND HAVEA PLACE IN COMMON THAT WE ALL REALLY LOVE.”STEVEN GOLDBLATT ʼ67PEYTON HOGEFor Marjorie, who traveled with hermother on a seven-month round-the-worldtrip after graduation and worked with artistGeorgia O’Keeffe for four months in NewMexico before attending McCormick TheologicalSeminary, this family interconnectionis beneficial: “It strengthens our commonbond, and it’s interesting to compare noteson our experiences. It fosters a sense of loyaltyto the College and its well-being. Now,with Jared beginning his college experience,it will enter our conversations more frequently."A National Merit Scholar and singer in achoral group that has toured Europe, Jared isconsidering a biology major or possibly aminor or double major in Spanish. “It’s beenespecially fun to try branching out," he said.“I was a bit concerned before I arrivedabout not knowing anyone, but it has beenreally fun to make new friends and getinvolved with things at the College," Jaredsaid. “Living with other students in thedorm is a much more social experience thanlife at home was, and it’s been great gettingto know new and interesting people."Jared has been singing in the Collegechorus and with Sixteen Feet, the all-male acappella group. “Feet has been one of themost enjoyable things I’ve ever done," hesaid. “My aunt was very involved in singingat College concerts, which I am doing now."According to Marjorie, “The commonbond of Swarthmore is significant in bothour immediate and extended family. TheCollege is certainly a common point of referencefor our families," she said. “In our case,the bond to Swarthmore includes the experienceof ‘village life’ as well. The seniorJoneses still live in Swarthmore, and bothmy mother and I still have friends who livethere. My husband and I were married in theSwarthmore Presbyterian Church.“Memories abound for all of us, yet ourmemories of both village and College differdepending on our specific experiences," sheadded. “We can still surprise each other withuntold stories, and it is fun to watch oldconnections come gradually to light for thenew generation."Jared said that “Sometimes talking aboutmy experiences will inspire others to tell storiesabout similar or related things. The commonconnection to Swarthmore does lead tosome interesting conversations, most oftenabout the way things have or haven’t changed."For example, his grandparents remember“more formal, family-style meals” and the“linen and cleaning service for men, althoughnot for women," Jared said. “I was a bit surprisedby that, but it seems like the Collegehas changed as society has changed over theyears. Still, some things—especially thetypes of people at Swarthmore and the generalexperience of being here—seem to bemore or less the same."M A R C H 2 0 0 219

1992 HALCYON 1940 HALCYONWith similar impressions, Marjorieechoed her nephew’s observations: “Swarthmorehas certainly changed over the years,as most colleges have. It has grown a greatdeal since my grandmother’s time, both insize of student body and in physical plant,"she said. “Its requirements and regulationshave changed—for example, since the timethat ‘three feet on the floor’ applied to a manand woman in the same room! What haschanged little are Swarthmore’s basic values:commitment to excellence in academics,top-flight faculty, low faculty-to-studentratios, balance in extracurricular activities,needs-blind admissions policy, the uniqueHonors program, and commitment toessential values of the Quaker tradition,"said Marjorie, a Presbyterian minister anddirector of the Pathways Center for SpiritualLeadership for Upper Room Ministries nearNashville. She has been particularly heartenedby the College’s increasing support ofcampus religious advisers from variousfaiths since the 1970s.Jean also marveled at changes on campussince she was a student. “Martin was thenew building when I was there, housingbiology, zoology, and psychology. Ourwomen’s gym was where the library is now,and the dining facility was where the AdmissionsOffice is. Wharton was there, andWorth was there—I lived there—but thereare new dorms over on what we knew as themen’s side of campus [Dana and Hallowell].“We had separate dorms for men andwomen. We had to sign out in the eveningand certainly if we were going anywhereovernight," she added. “We had fresh wholemilk and cookies or crackers delivered everynight at 10 to our dorms. Fraternity boyswould come to sing under our windows."Jean has also previously noted her concernabout the increasing costs at theCollege through the generations. “When1939 HALCYONJARED’S OTHER SWARTH-MORE RELATIVES INCLUDEHIS MATERNAL GRAND-PARENTS ED ’39 (TOPRIGHT) AND LYN PURDYJONES ’40 (TOP LEFT) ANDCOUSIN GUIAN MCKEE ’92(LEFT).Mother attended Swarthmore, it cost $400a year; when I was here, it cost $1,000 ayear; for Marjorie, $3,000-plus a year; andnow Jared, $34,000-plus."But she also recognized the ways thather Swarthmore education later supportedher family—particularly after they returnedfrom living in Thailand, Marjorie’s birthplace.“When I really needed a job, after arriving inSwarthmore with three kids, I really thinkthat being a Swarthmore graduate helpedme get the job I managed to get," she said.Remembering this pivotal time after herfather’s death, Marjorie said: “His deathoccasioned our move to Swarthmore fromoverseas, where he had been a missionary inThailand: “His loss was a terrible traumathat drew us even closer together. My motherpoured her life into her children, even asshe labored to make herself fit for a job inguidance counseling and later as a schoolpsychologist.“As children, we knew we were deeplyloved," she continued. “We learned themeaning of sacrifice and simplicity early on.In my view, faith was essential to our survival.These are enduring values that havepermeated our marriages and family life eversince. We all know the value of human lifeand love."S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NDescending from five generations ofSwarthmoreans, Sarah Fritsch ’04thinks that Swarthmore keeps her close tothe family’s Quaker roots. “I do feel thatwalking the same paths as my family beforeme has made me feel a stronger connection,"she says.These family ties trace back to 1868,when Sarah’s great-great-great aunt LydiaHart Yardley invested in SwarthmoreCollege by purchasing one share of stock inNovember of that year and a second shareseveral months later in 1869. In the followingyears, members of the family becamestudents at the College. The first was apparentlya great-great-great uncle of Sarah’s:Seymour Yardley Cadwallader, who attendedthe College in 1890 but died from tuberculosisas a student. He was followed by hisniece and Sarah’s deceased great-grandmotherElizabeth Cadwallader Wood ’11,whose daughter is Sarah Wood Fell ’49 andson John H. Wood Jr. ’37.“The choices that wehave made are verydifferent—each of ushas gotten a completelydifferent experiencefrom the same place.”THIS 1869 STOCK CERTIFICATE, SUBSCRIBING TOTHE COLLEGE CORP., WAS DISCOVERED WITH THEPAPERS OF ELIZABETH CADWALLADER WOOD ’11DAND BELONGED TO JOHN H. WOOD’S [’37] GREAT-AUNT LYDIA YARDLEY.Other relatives include Elizabeth’sdeceased brother J. Augustus Cadwallader,Class of 1913. His son is T. Sidney Cadwallader’36, who is class co-secretary with wifeCarolyn Keyes Cadwallader ’36.Further lengthening the family line,three of John H. Wood’s children are alsoSwarthmore graduates: John C. Wood ’67;Roger Wood ’69; and Elizabeth WoodFritsch ’73, Sarah’s mother. Susan YardleyWood (Tufts University ’79) was an exchangestudent at Swarthmore in her junior year.Supporting their Quaker roots, Sarah’sgrandfather, an attorney and partner atWood and Floge in Langhorne, Pa., is veryactive in various Quarterly and YearlyMeeting activities. Her mother is an attorneyand co-director of Legal Aid ofSoutheastern Pennsylvania. Her uncleRoger, an attorney at Dilworth Paxson LLPspecializing in business and banking law,also does committee work for the PhiladelphiaYearly Meeting.20

Sarah admits that her relatives’ “pleasantexperiences at Swarthmore" influenced herto apply. “However, its academic reputationwas probably the biggest factor and the locationas well—not too far from my home,"she says.Planning to pursue a career in diplomacyand international relations, specificallyinvolving French-speaking nations, Sarahalso wants to explore musical productionand composition when she graduates. Thismusical interest is shared by her mother,who sang in College concerts with MarjorieThompson ’74 (see the first family in thisstory).Roger, Sarah’s uncle, was particularlydrawn to Swarthmore because of the way itsupports individual differences. “I had beenon campus many times as a child and feltvery comfortable with the atmosphere there.As a result of conversations within the family,I believed that Swarthmore had many ofthe same values that were important in ourfamily, including a social awareness and tolerancefor individual differences, and I feltthat it would be a good fit for me," Rogersays.John C. Wood, Roger’s older brother andsenior consumer protection attorney at theFederal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C.,was an economics major—following thesame path as his father, which was latercontinued by his brother. The author of articlesthat have been published in the FederalReserve Bulletin and ABA Bank Compliance,he has also cultivated leisure interests suchas skiing, sailing, and tennis.Sharing some of these interests, Rogerwas a resident assistant on campus whodrove 350 miles to Vermont, during thewinter break in 1967, with Dean Robert Barr’56 and two other proctors to discuss studentlife and to ski. As a student, he alsowas a member of Student Council and ofDelta Upsilon. Today, Roger believes thatthe College should continue to encouragethe development of leadership abilities instudents.“My general impression is that Swarthmorehas remained the same with respect toits core liberal, social, and political values,"Roger says. “But that in recent years, it mayhave changed its educational mission byplacing greater emphasis than ever beforeon scholarship and academic achievementand possibly placing less importance on theSTEVEN GOLDBLATT ʼ67SARAH FRITSCH ’04 (FRONT); MOTHER ELIZABETHWOOD FRITSCH ’73 (BACK); AND GRANDPARENTSJEAN (LEFT) AND JOHN H. WOOD ’37 (RIGHT)GATHERED DURING THE WINTER HOLIDAYS IN THEIRLANGHORNE, PA., HOME. IN JANUARY, JEAN ANDJOHN WOOD TRAVELED TO THE HIGHLAND PARKCLUB IN FLORIDA, STARTED AROUND 1925 BY AGROUP OF SWARTHMORE GRADUATES.1911 HALCYONeducation of the whole person, includingthe development of leadership skills.Although this change has earned Swarthmorea preeminent national reputation asan elite academic institution, I think it representsa departure from the college thatearlier generations knew."Sarah is able to share some of thisknowledge about the past, gleaned fromfamily stories, with current classmates. “Ican provide a historical perspective for studentssometimes, when they have a questionabout why certain college policies arethe way they are now," she says.Sarah’s impression is that “Swarthmorealways comes up at family gatherings on mymother’s side," she says. “Among my relativeswho are alumni, it has created a sensethat I am experiencing things that they alsohave, which is comforting."Another advantage of this commonalityis that “when I mention events or places atSwarthmore, people understand me. I thinkit’s nice for my relatives to be able to checkup on how Swarthmore is functioning sincethey left and the changes that have occurred,"Sarah says.Her grandfather hopes that “Swarthmorewill always encourage its students tobe active in community service either directlyor indirectly," which was his own personaldream. Like others from his generation,he has also vehemently objected to the “skyrocketingcosts" of higher education.Traveling from his Langhorne, Pa., homein January, Sarah’s grandfather visited withsome of these classmates at the HighlandPark Club in Florida. The club, startedaround 1925 by a group of alumni, offerssnowbirds a haven during the wintermonths for playing golf, bridge, and croquettogether.“I don’t think Swarthmore has changedvery much because my mother, grandfather,and uncles seem to recognize most of thethings I talk about in reference to school,"says Sarah, whose work at the College issometimes compared by family memberswith her relatives’ performance. “I do,however, think the choices that we havemade are very different—each of us hasgotten a completely different experiencefrom the same place."BARBARA JOHNSTON1936 HALCYONMEMBERS OF THIS FIVE-GENERATION SWARTHMOREFAMILY INCLUDE (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) JOHNH. WOOD’S [’37] MOTHER, ELIZABETH CADWALLADERWOOD ’11D, HIS UNCLE J. AUGUSTUS CADWALLADER’13D; SISTER SARAH WOOD FELL ’49; SONS JOHN’67 AND ROGER ’69; AND T. SIDNEY CADWALLADER’36, A COUSIN WHO IS CLASS CO-SECRETARY.1913 HALCYON1949 HALCYONCOURTESY OF THE SCOTT ARBORETUMM A R C H 2 0 0 221

S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NIn another curving Swarthmorebranch, Ruth FeelyMerrill ’38 passed her love ofthe College on to three of eightchildren: Suzanne ’63, whomarried David Maybee ’62;Barbara ’69; and Chip ’71. “Ihave always loved going toSwarthmore and have includedmy family in these visits," Ruthsays.Suzi, director of communicationsat Holton-Arms Schoolin Bethesda, Md., recalls: “Iprobably made my first trip toSwarthmore when I was 6 or 7years old. My parents had justbuilt their home under the G.I.Bill and were picking out plantings.We spent several hours in the lilacgrove near the Friends Meetinghouse, findingjust the right color and scent for thelilacs we would plant at our new home. Insubsequent years, my mom seldom missed areunion or a Somerville Day…. Swarthmorebecame equivalent with college."Suzi’s college years shaped her own priorities.“My values and attitudes were chosenbecause they had meaning for me andthe adult I was becoming," she says. “Insome cases, family values were reinforced;however, by sending me to Swarthmore, myparents encouraged me to develop my own."The friendships formed on campus arestill the most important ones for Suzi andhusband Dave, a clinical reviewer at theCenter for Biologics Evaluation and Research.“My husband’s college roommatesare our closest friends—‘uncles’ and ‘aunts’to our children; my Robinson housematesstill gather to share important days; lacrosseand badminton coach Pete Hess welcomedme back to campus on my first day as aSwarthmore parent," Suzi says. “It was themanner in which people on campus interactedwith each other that had the greatestimpact on me as a person."The College’s academic and athletic programalso attracted four of Suzi and Dave’sfive children: Beth ’88, David Jr. ’89, Lynne’91, and Jill ’96. Interlacing Swarthmorefamilies again in the third generation, Bethmarried David Allgeier ’86 at Swarthmore’sUnited Methodist Church; they had daughterElizabeth in 1999 and son Matthew in2001. Extending this horizontal expansion,THE MAYBEE-NATHAN-ALLGEIER CREW GATHEREDFOR THIS PHOTO IN OCTOBER 1999. BACK ROW, LEFTTO RIGHT: LEN NATHAN ’92, LYNNE MAYBEE NATHAN’91, DAVID MAYBEE JR. ’89, BETH MAYBEE ’88, ANDDAVE ALLGEIER ’86. SECOND ROW, LEFT TO RIGHT:JILL MAYBEE ’96 AND GEOFFREY MAYBEE. SEATED:DAVID MAYBEE ’62, HOLDING ALYSSA NATHAN,AND SUZI MERRILL MAYBEE ’63, WITH ELIZABETHALLGEIER. MATTHEW ALLGEIER AND DANIELLENATHAN, BORN LAST SUMMER, ARE NOT SHOWN.Lynne married Leonard Nathan ’92; daughtersAlyssa and Danielle were born close totheir cousins’ births.“Each of our children was an individual—andtheir own person. I knew from theday they expressed interest in Swarthmorethat they would find their own way—theirown values and friendships—at the College.Their father and I needed to stand back,"Suzi says. “So we waited for invitations tovisit, and in all four cases, we were invitedand welcomed whenever we came. It wouldhave been wrong for us to expect our memoriesand experiences to be the same astheirs—but in the end, they have proved tobe quite similar."David Jr., who grew up surrounded bySwarthmore paraphernalia, thinks his family’spriorities of “autonomy, frugality, pursuitof intellectual interest, and belief in thepositive qualities of diversity of opinion"were reinforced by the College. But his generationdid not implicitly believe in “the wisdomof our elders and leaders" as did hisparents and grandparents’ classmates.Grandmother Ruth has “witnessedthe growth of the childrenas they mark their trails ineach of their separate ways."Changes she notes over theyears include Swarthmore’s largerstudent enrollment, exchangeprograms, and new buildings.But Ruth still thinks “Theessence of the College hasremained the same."Living on a 200-year-oldfarm in Stanton, N.J., for 30years—where the family oftengathered for reunions—Ruthvalues “the wonderful opportunitiesoffered the Garnet Sages"at the College. Some of theseinclude Alumni Weekend reunions,during which granddaughter Lynnehas driven golf carts. She also relishes memoriesof 1988, the year of her 50th reunionand Suzi’s 25th—when Beth graduatedfrom Swarthmore.Swarthmore’s Education professorsinfluenced Lang Scholar Beth, who taughtmiddle school for seven years. “They werewonderful mentors and models underwhom to develop a philosophy of education,"she says. Husband Dave, who workedin Swarthmore’s Alumni Office for fiveyears, is now a veterinarian. He stronglyopposed the College’s decision to eliminatefootball, voicing his anger in a letter to theBoard. Despite his disappointment, he alsosays that “classmates, teammates, professors,coaches, and colleagues at Swarthmorehad a huge effect on who I am and how Iconduct myself professionally and personally.Save my family and my church, Swarthmoreprobably shaped me more than anythingelse in my life."A certified athletic trainer now workingat the College, Lynne played soccer for fouryears as a student. Husband Len, an officerat MBNA America in Wilmington, Del., describessoccer on campus as “the nonacademicactivity that meant the most" to him.“Once you are accepted to Swarthmore,the real work begins," Lynne says, relatingglowing high school memories. “Then Icame to Swarthmore, where I was surroundedby the brightest from all over the world.If I hadn’t had faith in my own personalworth to carry me through, I could havebeen entirely eclipsed here."COURTESY OF THE SCOTT ARBORETUM22

Prepared for bumps, Lynne learned tocope with the challenges. “Having it sotough is part of what makes the Swarthmoreexperience such a worthwhile one,"she says. “I think you could ask any memberof my family if they would make the academicsless challenging, and we would sayno. We weren’t any of us looking for easy.Easy doesn’t teach you about your ownpotential," she adds.“The values and priorities that I learnedat home were reinforced at Swarthmore: tobe myself, to respect my peers, to take responsibilityfor my words and actions, toplay hard and work harder, and to value myfriendships with others," she says.The same qualities have carried into herwork life at the College, although disillusionmentand questions have shadowed herlove of Swarthmore since the athletics decision.“When did it become so important tomeet the standards set forth by othersinstead of walking our own path?" sheasks. Searching for renewed respect, Lynnehopes the administration will place studentsfirst by “giving them every opportunityto achieve their highest potential academically,artistically, and athletically."The campus first enchanted sister Jillafter her family returned from Hawaii,where they lived from 1976 to 1983. Thesummer they returned to the mainland,Jill’s grandmother took her on a campusvisit, when she discovered the amphitheater.“I left Swarthmore that day feeling like I hadleft my home," she says.Later College visits sustained this impression.“What amazes me most about Swarthmoreis that every relative … had a differentand unique experience. My siblings allattended the College at the same time andhardly saw each other unless they were tryingto," she says. “We all found differentsubjects and activities that interested us, andyet we can talk about Swarthmore andremember very similar experiences." Now inher fourth year at Temple University MedicalSchool, Jill played lacrosse at the College likeher mother and soccer like her sister. Despitechanges in Swarthmore’s “very dynamiccommunity, where ideas are constantlydebated by intelligent people," Jill thinksthat the College continues to draw students“with a passion for learning, a balancedapproach to life, and a unique sense of self."She adds: “I find all my siblings to be“The values learned athome were reinforcedat Swarthmore: to bemyself, respect mypeers, take responsibiltyfor my words andactions, play hard andwork harder, and valuemy friendships withothers.”IN 1988, GRANDMOTHER RUTH (LEFT) CELEBRATEDHER 50TH REUNION, WHILE DAUGHTER SUZI(RIGHT) ENJOYED HER 25TH AND GRAND-DAUGHTER BETH (CENTER) HER GRADUATION FROMSWARTHMORE.very unique, intelligent people; I think thesame qualities that led us to all have suchdifferent interests at Swarthmore are whatcontinue to make us interesting to eachother. Whenever we have a discussion over atopic, we each have our own slant on theissue, and we are all capable of disagreeingall night long if the mood strikes us."Reflecting on her own experience withclassmates and College life today, Suzi says:“It was the fellow students who were theessence of the College for me. There was amutual respect—for ideas, talents, opinions,diversity—among the people I knew atSwarthmore. We were all individuals. It wasOK not to conform, to think independently,and to explore new directions. I believe thatthis is still true today,"STEVEN GOLDBLATT ʼ67Suzi, who has served as an extern sponsoras has husband Dave, says: “But Swarthmore,like society, has its own particulargrowing pains and its own challenges; theseshow themselves in the controversies thatswirl through the campus from time to time.If the essence of Swarthmore remains as truetoday as it was in the 1960s, then it is theprocess—the listening, the discussion, andthe resolution of these issues—that will ultimatelyendure…. Sometimes the controversiesoverwhelm the basic mutual respect oncampus; we seem to be going through justsuch a time now. But I expect that, in theend, mutual respect will come through."Son David, now at the University ofMaryland School of Dentistry, agrees:“Many friends are very disappointed that atraditional sport that they held dear flew thecoop one night.... But graduates ofSwarthmore are purists and traditionalists,and they hold certain common values that Ithink are positive and constant—the mostsignificant is the validity of their voice."Despite any reservations, he would stillencourage the next generation to attendSwarthmore, valuing the “writing and reasoningskills" he developed as a student.Pondering her family’s continuing legacyat Swarthmore, his grandmother says, “I certainlyhope that they all will follow theirhearts and go somewhere that they can be ashappy and fulfilled as we have all been whoattended Swarthmore." Ruth adds, “Theuniqueness of Swarthmore and its willingnessto change has been experienced by eachin their own way."But the family’s still-mending woundgives Suzi pause. “Certainly, the recent ‘flap’over athletics and the impression that somehowathletes are undervalued as contributingmembers of the student body or thatthey are less qualified academically certainlyleaves a ‘bad taste’ for our family, where eachmember was involved in athletics to somedegree," she says. “Being an alum legacysometimes carried similar implications."Ultimately returning to the love ofSwarthmore that was instilled in her childhood,Suzi says, “My hope is that this will beresolved in a positive way so that at sometime in the next generation, one of mygrandchildren might find that Swarthmoreis just the right place to grow into adulthoodand to develop his or her particularpotential." TM A R C H 2 0 0 223

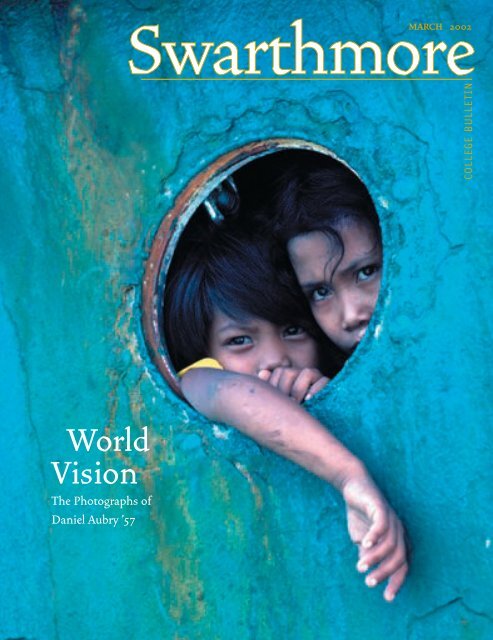

W O R L DV I S I O ND a n A u b r y ‘ 5 7 h a s c i r c l e d t h e p l a n e t i n s e a r c h o f g r e a t p i c t u r e s .S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I N24High Honors in history didn’t mean much in Hollywood,whereDan Aubry headed after graduation.He’d caught the film bug in college, where he andfriends made an 8-minute movie about a Ville barberwhose refusal to cut a black student’s hair became acause celebre on campus.After studying film at UCLA, Aubry worked in themovie industry, which he calls a “rough school where Ilearned a lot.” By 1960, he was in Spain, doctoring thescript of El Cid, the three-hour epic starring CharltonHeston. He later worked as a writer on projects with BillyWilder and Orson Welles, always yearning to be a director.“In hindsight,” he says matter-of-factly, “I blew alot of important opportunities in those years.”In the 1970s, Aubry left Hollywood for Spain, wherehe first sold real estate and later became head of thetourism board for Alméria, a province on the Andalusiancoast. “In the early post-Franco days, our organizationwas dirt poor,” he recalls. “If we wanted to do abrochure, I had to take the pictures. I’d always thoughtof myself as something of a photographer but had neverconsidered doing it professionally. When tourism boardsin neighboring provinces started asking me to photographfor them, and the government in Madrid startedcalling, I discovered it was a lot more fun than sittingbehind a desk.”Returning to the United States in 1980, Aubry devotedhimself full time to photography. He has traveled theworld in search of pictures, which have appeared inadvertising, magazines, and three of his own books. TheSpanish government remains one of his best clients.Another client—Sheraton Hotels—commissioned him tophotograph 33 of its properties in the Middle East andAfrica, a project that took two years and resulted inanother book. Aubry has also pursued fine-art photographyand has had two one-man shows at the MoniqueGoldstrom Gallery in New York.For Aubry, photography is more than light, color, andcomposition. In his pictures—and recently in new mediasuch as video and digital photo-collages on glass—hetells stories. Taken together, his photographs tell a largerstory—his own.—Jeffrey LottLeft: Petrified wood in a desolate landscape, Patagonia, Argentina.Top right: One of the famous flying horses (cabriola) in Jerez, Spain.Right: Banana vendor, Abuja, Nigeria. Far right: A rare white gorillain the Barcelona zoo.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS © DANIEL AUBRYM A R C H 2 0 0 225

S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I N26

Left: The Miramar Resort in El Gouma, Egypt, designed by theAmerican architect Michael Graves. Right,top to bottom: Folkdancer in Mexico City. Indian girl, Sultanate of Oman. Childand her nanny, St. Bart’s, Caribbean. Below: A warrior in theSepik River region of Papua New Guinea.To see more Daniel Aubry photos, visit his Web siteat www.danielaubrystudio.com.M A R C H 2 0 0 2ALL PHOTOGRAPHS © DANIEL AUBRY27

S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NOn Sept. 11, 2001, Dan Aubry was in his23rd Street studio in Manhattan. “I’m not ajournalist,” he says, “so I didn’t run out withmy camera when I heard the first news. Wewatched from the roof of our building as theTrade Centers collapsed.” Like many New Yorkersin the weeks following the terroristattack, Aubry was moved by stories of individualheroism and loss—stories that were madepainfully real by thousands of homemademissing posters that appeared throughout thecity. He decided to design a visual memorialto the victims. Since September, his idea for aWorld Trade Center Visual Memorial—a walkthroughmultimedia exhibit—has gatheredsupport. To learn more about the memorialplans, use Internet Explorer to visit www.-wtcvisualmemorial.org.28

The Parthenon, AthensALL PHOTOGRAPHS © DANIEL AUBRYM A R C H 2 0 0 229

TheDoubtingWarT w o S w a r t h m o r e a n s h a v e i n c r e a s e dp u b l i c a w a r e n e s s o f o b s e s s i v e - c o m p u l s i v ed i s o r d e r i n c h i l d r e n .By Marcia RingelS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I N© LAURA STOJANOVIC30