Swarthmore College Bulletin (June 1998) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (June 1998) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (June 1998) - ITS

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

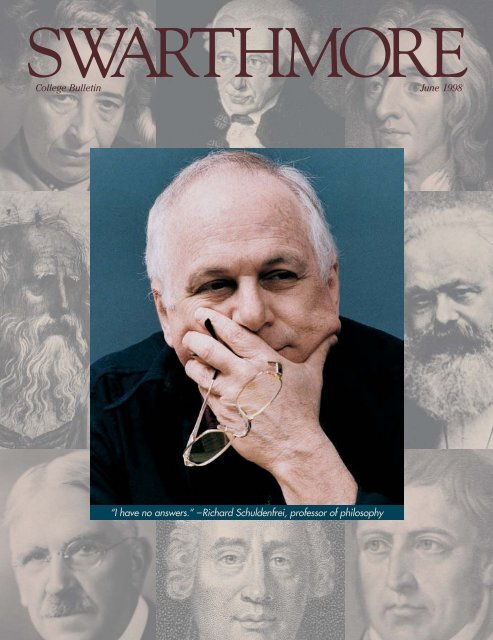

Editor: Jeffrey LottAssociate Editor: Nancy Lehman ’87News Editor: Kate DowningClass Notes Editor: Andrea HammerDesktop Publishing: Audree PennerDesigner: Bob WoodIntern: Jim Harker ’99Editor Emerita:Maralyn Orbison Gillespie ’49Associate Vice Presidentfor External Affairs:Barbara Haddad Ryan ’59Cover: Professor Richard Schuldenfreisays he’s not a philosopher—hejust teaches philosophy. The ideashe brings to class come from a pantheonof great thinkers, some ofwhom surround him here. Clockwisefrom top left (with appropriate credits),they are Hannah Arendt (UPI/CORBIS-BETTMANN), Immanuel Kant(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/CORBIS), John Locke(CORBIS-BETTMANN), Karl Marx (CORBIS-BETTMANN), Wilhelm Hegel (CORBIS-BETTMANN), David Hume (LIBRARY OFCONGRESS/CORBIS), John Dewey (LIBRARYOF CONGRESS/ CORBIS), and Plato (CORBIS-BETTMANN). The photo of Schuldenfreiis by Deng-Jeng Lee.Changes of Address:Send address label along with newaddress to: Alumni Records,<strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong>, 500 <strong>College</strong>Avenue, <strong>Swarthmore</strong> PA 19081-1397.Phone: (610) 328-8435. Or e-mailalumnirecords@swarthmore.edu.Contacting <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong>:<strong>College</strong> Operator: (610) 328-8000Admissions: (610) 328-8300admissions@swarthmore.eduAlumni Relations: (610) 328-8402alumni@swarthmore.eduPublications: (610) 328-8568bulletin@swarthmore.eduRegistrar: (610) 328-8297registrar@swarthmore.edu©<strong>1998</strong> <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong>Printed in U.S.A. on recycled paperThe <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong>(ISSN 0888-2126), of which this is volumeXCV, number 5, is published inAugust, September, December, March,and <strong>June</strong> by <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong>, 500<strong>College</strong> Avenue, <strong>Swarthmore</strong> PA19081-1397. Periodicals postage paidat <strong>Swarthmore</strong> PA and additionalmailing offices. Permit No. 0530-620.SWARTHMORECOLLEGE BULLETIN • JUNE <strong>1998</strong>10 How Do You Live a Good Life?For more than 30 years, Philosophy Professor Richie Schuldenfreihas been asking <strong>Swarthmore</strong> students that question. They don’tleave with the answers. What they get are ideas about how todefine a moral life and how to measure their own lives against it.By Vicki Glembocki14 Home Is the SpiritLaura Markowitz ’85 came out as a lesbian in her junior year at<strong>Swarthmore</strong>. At the 10th annual Sager Symposium, she recalledher early “emotional homelessness” and the process of cominghome psychologically to her family and friends—and the <strong>College</strong>.By Laura Markowitz ’8520 Can’t a <strong>College</strong> Be More Like a Business?Significant economic differences exist between an institution ofhigher learning and a for-profit corporation. Paul Aslanian, vicepresident for finance and planning, explains the reasons, basedon the <strong>College</strong>’s choice to remain small yet of the highest quality.By Jeffrey Lott64 What Lucretia Mott Means to MeShe spoke on women’s rights, asked for stronger action againstslavery, and fought for American Indian rights. Jamie Stiehm ’82talks about her love of the Quaker woman who helped found the<strong>College</strong> and was a major player on every front of social progress.By Jamie Stiehm ’822 Letters4 Collection24 Alumni Digest29 Class Notes32 Deaths58 Recent Books by Alumni

T E R SPericles’ funeral speech. I had beento dinner with him and his lovelywife and had walked with him alongthe Crum.But it wasn’t until I walked intohis office one afternoon andannounced that I had decided toleave <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong> that Itook a fuller measure of the man.He immediately telephoned thesource of my trouble and, with afirmness and command that surprisedme, reversed my apparentmisfortune and saved me from astupid act I would have regrettedthe rest of my life.I’m sure he has his faults. Who iswithout faults? He is also one of thefinest human beings I have everknown.MIKE PETRILLA ’73Upper Darby, Pa.A rare giftTo the Editor:David Wright’s [’69] fine tribute toGilmore Stott stirred warm feelingsin me. My respect, love, and appreciationfor Dean Stott have grown asI have grown and as I have come tounderstand what is rare in theworld and what is common. Whathe gave to me is rare.I was the first in my family toattend college. Dean Stott affirmedme as a person when he encouragedme to come to <strong>Swarthmore</strong>during an interview during mysenior year in high school. Hisincredibly soft, deep voice soothedme as I looked with trepidation atmy future college experience.I don’t remember talking withDean Stott much during my time at<strong>Swarthmore</strong>. But in the spring of myjunior year, after we had tied PennState in lacrosse, my roommate toldme the following: Dean Stott, sittingin the stands next to my roommate,asked who had made the goal to tiethe game. When given my name, heremarked something to the effect, “Iknew he could do it!” That pronouncement,though not heard byme personally, has been an inspirationto me throughout my life. Ihave drawn on it in times of selfdoubt.WILLIAM J. BOEHMLER ’60Wyomissing, Pa.JUNE <strong>1998</strong>More letters on page 26P O S T I N G SAreport released in April by a commissioncreated by the CarnegieFoundation for the Advancement ofTeaching sharply criticized the teachingof undergraduates at research universities.By implication it said that liberalarts colleges were doing the best sort ofteaching, combining close interactionwith professors and opportunities to doreal research at the undergraduate level.Some excerpts of the report follow:• In a great many ways, the highereducation system of the United Statesis the most remarkable in the world....Half of the high school graduates in theUnited States now gain some experiencein colleges and universities;we are, as acountry, attempting tocreate an educated populationon a scale neverknown before....• The country’s 125research universitiesmake up only 3 percentof the total number ofinstitutions of higherlearning, yet they confer32 percent of the baccalaureatedegrees....• Nevertheless, theresearch universitieshave too often failed, andcontinue to fail, theirundergraduate populations.... Recruitmentmaterials display proudly theworld-famous professors, the splendidfacilities, and the ground-breakingresearch that goes on within them, butthousands ... graduate without everseeing the world-famous professors ortasting genuine research....• Many students graduate ... lackinga coherent body of knowledge or anyinkling as to how one sort of informationmight relate to others. And all toooften they graduate without knowinghow to think logically, write clearly, orspeak coherently....• These are not problems that havebeen totally denied or ignored; there isprobably no research university in thecountry that has not appointed facultycommittees and created study groupsor hired consultants to address theneeds of its undergraduates.... Even so,for the most part fundamental changehas been shunned....• Every research university canpoint with pride to the able teachersIt seemsthe smallliberal artscollegeis doingsomethingright.within its ranks, but it is in researchgrants, books, articles, papers, andcitations that every university definesits true worth. When students are considered,it is the graduate studentsthat really matter....• What is needed now is a newmodel of undergraduate education atresearch universities that makes thebaccalaureate experience an inseparablepart of an integrated whole.• There needs to be a symbioticrelationship between all the participantsin university learning that willprovide a new kind of undergraduateexperience available only at researchinstitutions. Moreover,productive research facultiesmight find newstimulation and new creativityin contact withbright, imaginative, andeager baccalaureate students,and graduate studentswould benefit fromintegrating their researchand teaching experiences....And from the report’sconclusion:• Captivated by theexcitement and the rewardsof the researchmission, research universitieshave not seriously attempted tothink through what that mission mightmean for undergraduates. They haveaccepted without meaningful debate amodel of undergraduate educationthat is deemed successful at the liberalarts colleges, but they have found itawkward to emulate. The liberal artsmodel required a certain intimacy ofscale to operate at its best, and theresearch universities often find themselvesswamped by numbers. Themodel demands a commitment to theintellectual growth of individual students,both in the classroom and out, acommitment that is hard to accommodate....Almost without realizing it,research universities find themselvesin the last half of the century operatinglarge, often hugely extended undergraduateprograms as though they aresideshows to the main event....The commission’s full report is availableon the World Wide Web at http://notes.cc.sunysb.edu/Pres/boyer.nsf.3

COLLECTIONS W A R T H M O R E T O D A YRobert Gross ’62 named dean of the <strong>College</strong>Robert J. Gross ’62, who for the past year has served asacting dean of the <strong>College</strong>, has been named dean.In making the announcement last month, PresidentAlfred H. Bloom said, “We look forward to the extraordinaryimpact of Bob’s wise and humane leadership in furtheringthe <strong>College</strong>’s ability to respond to the personal and academicneeds and aspirations of students, and in enabling<strong>Swarthmore</strong> to be a model of an inclusive, generous, andprincipled community.”Gross had been associate dean of the <strong>College</strong> since 1991and became acting dean last <strong>June</strong> when Dean Ngina Lythcottresigned.After receiving an M.A.T. and an Ed.D. from Harvard andserving a stint as director of secondary teacher educationat SUNY at Stony Brook, he joined the <strong>Swarthmore</strong> facultyin 1977 as assistant professor of education. After six yearsGross left to become head of the upper school at FriendsSelect School in Philadelphia. He was working on finishing amaster’s degree from the Bryn Mawr Graduate School ofSocial Work when the associate deanship at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>became available seven years ago.At Parents Weekend last year, Gross talked about his philosophyof helping students develop. “The deans, I believe,play a special role in modulating the balance between challengeand support. Proactively we may design resident lifeprograms. Or we may work with faculty on advising andacademic support systems, or work with student groups ondiversity training. Or we may react to roommate crises, academicmeltdown, or existential angst. But we always try tobe sensitive to the developmental process. Thus the Dean’sPrayer: ‘Lord, give me the strength to afflict the comfortable,the compassion to comfort the afflicted, and the wisdomto know who needs what.’”Gross says of the art of being a dean: “We need to provideenough support so the challenges are accessible and achievablebut not so much support that students fail to develop autonomy.”ELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSNew <strong>College</strong> librarian Peggy SeidenOne for the books: <strong>College</strong>selects new librarianArmed with both library and educationalcomputing experience, Peggy Seiden joinsthe <strong>College</strong> as the new librarian. She is currentlycollege librarian at Skidmore <strong>College</strong>.A graduate of Colby <strong>College</strong>, Seiden holds anM.A. from the University of Toronto and a masterof library and information science from Rutgers.She has been at Skidmore for the past sixyears. Prior to that she was head librarian at thePenn State campus in New Kensington, Pa. Seidenalso worked at Carnegie Mellon University,where she was librarian for educational computing,reference librarian, and software manager.She will begin her duties at <strong>Swarthmore</strong> laterthis summer.4 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

A year in the Dean's Office:an ethnographic experienceBy Joy Charlton, professor of sociologyIt’s been with considerable professional and intellectualinterest that I’ve spent the past year as interim associatedean for academic affairs, working with students inways that I normally don’t as a faculty member andobserving aspects of the <strong>College</strong> that professors seldomsee.When asked about my year in the Dean’s Office, I’veoften replied that I’m having an “ethnographic experience.”Ethnographic research—studying social groups bymeans of participant observation and interviewing—iswhat I like to do as a sociologist; substantivelymy research interests haveincluded studying work and organizations.So I’ve been thinking about someof the same issues involved in my professionalresearch—about work, itsmeaning, and its challenges—only thistime with students’ work and deans’work as the focus. Part of the fun of thisyear has been to sometimes serve as abridge between faculty, staff, and students.Given the organization of the <strong>College</strong>and its division of labor, aspects ofwhat we all do remain invisible to eachother.As a faculty member, I think primarilyabout students’ development in theintellectual realm and about my ownacademic territory. As a dean I’velearned more about the richness andcomplexity of students’ lives, which aremore complex than I had ever imagined.This year I’ve observed many studentssuccessfully accomplishing 87 taskssimultaneously, working on multiplemajors, concentrations, theses, communityservice, internships, athletics, participationin student organizations, andmaintenance of personal relationships.And I’ve come to see how complex thereasons can be when students are notsuccessfully completing their tasks, particularly the academicones. Because any student admitted to <strong>Swarthmore</strong> is,we assume, capable of doing the work here, academic difficultyalmost always involves other difficulties that interferewith academic success.As a dean I have come to more fully appreciate how difficultthe first year of college is. Going to college is a centralrite of passage from adolescence to adulthood, fromfamily to independence. Our students make this transitionin an environment that is, in some ways, benign and protected(as parents hope) but is also fraught and pressurefilled (as students fear). Students are rigorously challengedto perform intellectually, even while still unfamiliarwith student skills particular to <strong>Swarthmore</strong>, and they arealso challenged to make choices—on their own, to lesser“Students’ lives are more complex thanI had ever imagined,” says ProfessorJoy Charlton, who spent the past yearin the Dean’s Office as interim associatedean for academic affairs. Thisarticle is adapted from a talk she gaveon Parents Weekend in April.and greater degrees—about their identities, their socialrelations, their political positions, their sexuality, and theirfuture. And they have to do all of these things at the sametime.Meanwhile some of our students are dealing with extraordinarilydifficult personal problems, some of which areat home. It is not uncommon for parents, having stayedtogether “for the sake of the children,” to choose thismoment to dissolve a marriage, precisely because the childrenhave now left home. The impact on the college studentcan nonetheless be profound.In addition, more students than I had previously understoodsuffer from clinically diagnosed psychological problems,particularly depression. Why so many Americanadolescents should be clinically depressed is, I think, astory worth trying to understand; as asociologist I can’t help but think thatthe way we organize schooling in oursociety must be an enormous contributor.Some of our students seem toarrive with a sense of burnout already.Having worked so diligently as highschool students to get to the college oftheir choice, some seem to be tired andat a loss once they’ve made it.And bereavement. I think of our studentsas young and their parents asyoung; however, more students than Iwould have imagined are coping withthe recent or imminent death of a parentor other immediate family member.We as a culture don’t provide much inthe way of time or rituals to help eachother adjust to such losses.It’s often difficult to know whetherwhat’s going on with a student—or students,collectively—is normal developmentalprogress, normal adjustment tostress, or serious abnormal psychologicaldifficulty that requires professionalintervention. Deans routinely makejudgment calls about how to respond tostudents, just as faculty members dowhen they decide whether a student’sdifficulty calls for extending a deadlineor for holding the line in the interest ofequity for all students. But I’ve learned that neither facultyexperience nor good instincts alone are enough for doinga dean’s job well. Doing the job well requires experience,and not a day has gone by that I haven’t asked some memberof the dean’s staff for information or advice.Which leads me to something else I’ve learned: Thedean’s staff members at <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong> are verygood at what they do. As a group, and with the faculty,they work hard, and sometimes invisibly, to support theacademic enterprise here. And they work collaborativelyin a way that has been a great comfort to me, as I hope itis to students, parents, and alumni.Spending the year learning about the work lives of studentsand staff and faculty has led me to greater compassionand respect for all of us.JUNE <strong>1998</strong> 5

COLLECTIONALL PHOTOS FROM HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF THE JEWISH AUTONOMOUS REGION, BIROBIDZHANHow the Soviet Union triedto make a Jewish homelandand publications in both Russian andYiddish.Incentives to the Jews included providingmigrants and their families witheither free or significantly discountedtravel and food subsidies. The governmentalso extended credit, tax exemption,and other material benefits tothose who engaged in agriculture.“But the authorities did little to preparethe newcomers, most of whomhad no agricultural experience, for thehardships in an unknown and forbiddingregion,” Weinberg said. “Nor didthey provide the settlers with decenthousing, food, medical care, and workingconditions.”The population, continually searchingfor viable niches outside agriculture,either left the countryside for lifein one of the larger cities in the regionor returned home. Moreover, by 1939Jews accounted for only slightly morethan 15 percent of the region’s population,composed primarily of Russiansand Ukrainians. “The plan to resettlelarge numbers of Jews on the land wasstillborn,” Weinberg said.Despite the failure in creating anagricultural utopia, some Soviet Jewsremained interested in a Jewish homelandwithin the Soviet Union, especiallyafter World War II, when “personal lossand a sense of tragedy motivated manyprospective migrants to seek new livesin a new venue.”But by 1948 Stalin began conductinga murderous campaign to destroy allJewish intellectual and cultural activitythroughout the Soviet Union. By thetime he died in 1953, the Birobidzhanexperiment had been dealt a mortalblow.Today, says Weinberg, only a smallpart of the region’s population is Jewish.Many who have left the JAR havegone to Israel, diminishing the prospectsof revitalizing a Jewish community.Says Weinberg: “There is no signthat the official designation of the JARwill be taken away, but the state ofaffairs strongly suggests that the futureof Jewish life in the region is bleak.Notwithstanding a positive turn ofevents since the collapse of the SovietUnion, the hopes and aspirations thatso many of the pioneer Jews placed inthe Birobidzhan experiment still havenot been fulfilled.”Clockwise from top: In the 1930s JARauthorities tried to show satisfied and happysettlers; two Soviet propaganda posters, thefirst urging settlers to “Build a socialist Birobidzhan”and the second proclaiming, “Letus give millions to settle poor Jews on theland and to attract them to industry.”JUNE <strong>1998</strong> 7

COLLECTIONELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSWired ... When senior Allison Marshsearched for a way to pique interest inscience among school children, shedecided to think small. Armed with a$1,000 grant from AT&T and the Instituteof Electronics and Electrical Engineers,Marsh wired her childhood dollhouse,modeling the National ElectricCode to scale (1 inch equals 1 foot).“I’ve made this as a teaching tool,”Marsh said, “to explain how a house iswired and show how switches interact.”The control panel is color coded,with large appliances, such as theoven or clothes dryer, getting their owncircuits. Using a computer simulation,she’s able to determine which branchoutlets draw the most—and theleast—in monthly consumption. A doublemajor in history and engineering,Marsh has won a Watson Fellowship,with which she hopes to combine bothmajors in producing an engineers’guide to Europe.ELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSWomen's track and field team capturesits first Centennial Conference outdoor titleCatherine Lainé ’98 led thewomen’s track and field team toits first-ever Centennial Conference(CC) outdoor crown by earningPerformer of the Meet honors. Lainéwon the 400-meter run, setting a new CCrecord of 58.36 seconds, and ran a legon the winning 4 x 100 relay squad withDanielle Duffy ’98, Desiree Peterkin ’00,and Wonda Joseph ’00. She also finishedsecond in the 400-meter hurdles, longjump, and triple jump. Peterkin was awinner in the long jump and the triplejump, setting conference records inboth events. Peterkin topped her ownmark in setting a school record in thetriple jump with a leap of 37'6.5", justedging Lainé by half an inch. Both athletesqualified for the NCAA Division IIIChampionships. Head coach Ted Dixonwas honored as the <strong>1998</strong> USTCAMideast Regional Women’s OutdoorCoach of the Year in guiding the Garnetto a 5-0 record and the CC Championship.At the NCAA Championships, bothPeterkin and Lainé earned All-Americanhonors.The men’s track and field team posteda season record of 4-1 and placedfourth at the conference championships.Steve Dawson ’00 led the Garnetwith a second-place finish in the highjump, a fourth-place finish in the longjump, and fifth place in triple jump.Mason Tootell ’99 placed third in the110-meter hurdles, fourth in the 400-meter hurdles, and fifth in the longjump. George Bealefeld ’99 placed fourthin the shot put, and Keith Gilmore ’01ran fourth in the 400-meter run.The women’s lacrosse team qualifiedfor the ECAC Mid-Atlantic Championshipfor the second consecutive season.The Garnet lost a 12-11 overtime heartbreakerto Drew University in the firstround of the ECAC Championships tofinish the season at 10-7. The trio ofHolly Baker ’99, Betsy Rosenbaum ’98,and Alicia Googins ’00 led the squad onoffense, scoring goals in all 17 games.Baker led the Garnet with a career-best72 goals and 21 assists for 93 points toearn Second-Team All-American, First-Team All-Region, and First-Team All-Centennialhonors. Baker now ranks fourthon the <strong>Swarthmore</strong> career points list,with 155 goals and 57 assists. Rosenbaumscored a career-best 60 goals and18 assists for 78 points to finish 10th onthe Garnet all-time scoring list, with 94goals and 38 assists. Googins netted acareer-best 53 goals and 20 assists for73 points to earn Second-Team RegionalAll-American honors. Sarah Singleton ’99was named to the Second-Team All-Region and Second-Team All-Centennialsquads, and Jane Kendall ’00 earnedSecond-Team All-Regional and Centennialhonors.The men’s lacrosse team posted a3-12 overall record and a 1-5 mark in theCC. The Garnet Tide snapped a 16-gamelosing streak, with an 8-7 victoryat Shenandoah, and earned their firstCC victory since the 1995 season with a12-4 win over Dickinson. The GarnetDanielle Duffy ’98 won this year’s GladysIrish Award. A three-time Centennial ConferenceMVP in field hockey, co-captainDuffy led the team to three consecutiveconference championships and earnedFirst-Team All-American honors. Duffy alsoco-captained the women’s track and fieldteam, capturing three Outstanding Performerof the Meet awards, leading thesquad to two indoor Centennial championshipsand this year’s outdoor title. Sheholds six Centennial and nine <strong>Swarthmore</strong>records in indoor and outdoor events.A biochemistry major, Duffy is also athree-time regional Academic All-Americaselection. She was also named to the 1997GTE Academic All-America Fall/Winter At-Large First Team. She will attend medicalschool at the University of Pennsylvania.8 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

players were led onoffense by Mark Dingfield’01 and Mike Lloyd’01. Dingfield scored 28goals and eight assistsfor 38 points to lead theTide, and Lloyd tallied18 goals and 12 assistsfor 30 points. MidfielderAlex DeShields ’98 ledthe squad with 134ground balls, and defenderAaron Hultgren’98 led the defense with51 ground balls. Defensivestalwart TuckerZengerle ’00 receivedCC Honorable Mentionrecognition. GoalkeeperSig Rydquist ’00 posted13.33 goals againstaverage while turningaway 178 shots andscored a goal.The men’s tennisteam reached the NCAATournament for the20th consecutive year,the 24th time in the last25 seasons. The thirdseededGarnet traveledto Amherst, Mass., totake on the host teamin the NCAA EastRegional Championships.The Garnet led1-0 after the teams ofGreg Emkey ’99 andPeter Schilla ’01 andDennis Mook ’01 andJon Temin ’00 were victorious, eachby an 8-4 margin, to capture the doublespoint. However, the Lord Jeffs won thefirst four singles matches to win 4-1. TheGarnet sent a contingent of four playersto the NCAA Division III IndividualChampionships. The doubles team ofJohn Leary ’00 and Temin, ranking secondin the East Regional, bowed out inthe round of 16. The Garnet finished theseason with a record of 9-9.The women’s tennis team posted an11-4 overall record and was 8-2 in the CCto finish in a tie for second place. JenniferPao ’01 reached the finals of theCentennial Individual Championships,where she placed second and wasnamed First-Team All-Centennial. Paoposted a 10-2 overall record at No. 1 singlesand went 7-1 in CC competition.Wendy Kemp ’99 was perfect in CC play,posting a 7-0 record at No. 4 singles anda 10-1 overall mark, andKrista Hollis ’01 reachedthe quarterfinals of theCC Championship andfinished the season witha 9-3 mark. Hollis andPao teamed to post an8-2 CC and 12-2 overalldoubles mark, earningSecond-Team All-Centennialhonors. The team ofRani Shankar ’98 andLaura Brown ’00 reachedthe semifinals of the CCDoubles Championship.In singles play Brownwas 9-1 overall at No. 5singles and 5-1 in CCplay.The softball teamposted a 10-23 mark, capturingits most winssince the 1992 season.Co-captain MichelleWalsh ’98 hit .500 (56 of112), with 52 RBIs, 13doubles, seven triples,four home runs, and a.848 slugging percentage.Walsh led the CC in overallaverage, RBIs, andtriples and finished inCatherine Lainé ’98 second place in doublesset a Centennial Conference and home runs to earnrecord of 58.36 seconds in the Second-Team All-Centennialhonors. Co-captain400-meter run, winningPerformer of the Meet honors Dana Lehman ’98 led theand leading <strong>Swarthmore</strong> to its CC with 172.1 inningsfirst-ever conference title. pitched and was secondwith 68 strikeouts toearn Second-Team All-Centennial honors.The baseball team started out hot,winning its first three games in Florida,but then lost 22 games in a row beforesnapping the streak with a 4-2 win atHaverford. The Garnet finished the seasonwith an overall record of 4-25. JoshRoth ’99 led the team with a .365 battingaverage and four triples.The golf team posted an 8-7 mark tocapture its first winning season since1987. Matt Kaufman ’01 led the Garnetwith an 82.4 average, recording teammedalist honors in six of seven matchesincluding a season best 73 in a victoryover Widener University.The Garnet tied Haverford 9.5-9.5 inthis year’s Hood Trophy competition,and thus the Fords retain the bowl foranother year.—Mark DuzenskiMARK DUZENSKINew tennis and fitness center ...Ground was broken this month for anindoor tennis facility that will housethree courts and a 4,000- square-footfitness area. The building, which willbe located behind Ware Pool, isexpected to open in February 1999.Principal donor Jerome Kohlberg ’46has asked that the facility be namedthe Mullan Tennis Center, in honor oflongtime tennis coach and professorof physical education Mike Mullan.The center will feature championshipcalibercourt surfaces, lighting, andspacing.They really like us! ... A record of4,578 applications for admission werereceived by the <strong>College</strong> for the Classof 2002. Of those, 888 students(including 142 notified during earlydecision periods) were accepted.Based on previous admissions patterns,the <strong>College</strong> expects to yield afirst-year class of 360. More of theadmitted students declared “undecided”as their intended major than anyother. Next, in order of popularity, areengineering, biology, English, andpolitical science.And the champ is ... <strong>Swarthmore</strong>,which bested 45 other colleges anduniversities to win this year’s NationalAcademic Quiz Tournament undergraduatechampionship. Members ofthe winning team included seniorsFred Bush and Joe Robins, junior EdCohn, and sophomore John Miller.The tournament is the largest andmost active <strong>College</strong> Bowl league inthe country.To your health ... Of the 45 <strong>Swarthmore</strong>students and alumni whoapplied to medical school throughthe <strong>College</strong>’s Health Sciences Office,76 percent were accepted for admissionlast fall. This was an increaseover last year’s acceptance rate of 63percent and twice the national rate of37 percent.JUNE <strong>1998</strong> 9

HOW DO YOULIVE AGOOD LIFE?Philosophy professor Richard Schuldenfrei has been asking<strong>Swarthmore</strong> students this question for 30 years.Richie Schuldenfrei is pacing. Hespeaks slowly, reminding hisclass where the discussionended last time, stretching out histhoughts, long and careful and quiet.“For a long time ... moral philosophy ...caught between Kant and Hume.”A student, tardy and knowing it,appears at the door and sits sheepishlyin a nearby chair. A few secondslater, another appears, tardy andknowing it and not caring, and sauntersto a seat in the front where hepulls a sandwich out of his bag. Richiedoesn’t look at them. In fact, he hasn’tlooked in the eyes of any of the studentsin the random semicircle ofchairs in 324 Papazian. He’s stillwarming up.He rolls up the sleeves of his navyblueshirt, hanging boxy over a wornpair of Levis. Still pacing. “The basicview ... virtue ethics ... what is rightand just.” He knows they remember.He knows they’re clear on virtueethics. He knows they understand thedifference between the theories ofKant and Hume, between a life drivenby duty and a life driven by comfort.He knows they’re prepared. He’s theone who needs to pace, who needs tofind the pace, the momentum. Especiallytoday, the third-to-last class ofthe semester. The school year, thestudents, are all winding down. Wearingout. So is Richie. And today it’sraining.He stops behind the podium. Heputs on his glasses, glances at hisnotes. He takes off his glasses, holdsthem in his left hand. He looks up,ready now, leaning forward farenough that the podium balances onone thin edge. Then, the question:“How do you live a good life?”The question.Richie Schuldenfrei has been asking<strong>Swarthmore</strong> students this questionfor 30 years. And for 30 years,he’s been asking himself as well.Schuldenfrei is not a philosopher.He just teaches philosophy. Atleast that’s what he says after class,sitting in his office, in his trademarkblack leather swivel chair, a chunk ofcardboard holding up one leg. A philosopher’schair. The place where for30 years he’s chatted and argued andcounseled students, backed by a walllined with Plato and Aristotle andLocke and Rousseau and Hegel andNeitzsche and Dewey and Kant andHume. “I have no answers,” he says.What Richie does have is a following.The senior class has selected himas the faculty speaker at Last Collectionfour times. Then there’s the list of58 alumni who consider Richie to betheir greatest <strong>Swarthmore</strong> influence.The list is impressive for its numberand its range—some who graduatedin the early ’70s and some who graduatedjust a few years ago.“I don’t think a week goes by whensomething in my professional interactionsdoesn’t get me thinking aboutRichie,” says Vishu Lingappa ’75, aphysiology professor at the Universityof California. “He constantly questionedhimself ... and us. I’ve taken onthis trait of his. I thrived on it. He and Iwould walk around campus and talkabout Hume or Hegel or something weBy Vicki Glembockiwere studying in class. An hour wouldgo by, us wandering around, arguing.”“He taught us what philosophyshould be,” says Noah Efron ’82, whoteaches history of science at MIT. “It’sa set of personal questions thatbecomes personal obsessions aboutthe way you live your life.”For Richie, philosophy is personal.Teaching it is personal. “I want toteach them something that they cantake away with them. I want to helpteach them something that’s going tomake a difference in their lives, notjust a little patch of knowledge thatthey’ll never have any reason to bringup to live memory in the future,” heexplains.Teaching students “somethingthat’s going to make a difference intheir lives.” The words ring with thesweet and noble naïveté of a youngprofessor, fresh out of grad school,but Richie never fit that picture. Hearrived at <strong>Swarthmore</strong> in 1966 a “reddiaperbaby with a radical disposition”—andwith a bachelor’s and master’sfrom Penn and a doctorate fromthe University of Pittsburgh.He says he fit right in with <strong>Swarthmore</strong>students then, when their tonewas what he describes as “an olderform of American radicalism, somethingbetween American populismand a classical sort of left-wing politics.”When politics came to the forein the late ’60s, Richie was drawn tothe radical side, “fumbling my way toexplicit Marxism.”“Every day students made connectionsbetween what they were learningin the classroom and what theywere hearing on the news,” says Bob10 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

DENG-JENG LEEDiPrete ’70, now director of the OregonHealth Council. “After the U.S.invasion of Cambodia [in April 1970],students went on strike. The reasonwe weren’t attending class wasbecause of what we were learningfrom Richie—he had such a rigorouscode for holding himself responsible.It became necessary for us to take astand.... We had to hold ourselvesaccountable.”Ultimately, Richie couldn’t helpexamining what he was thinking andteaching in light of the bloodbath thatfollowed in Cambodia. Looking backhe thinks the story sounds clichéd,and he is almost embarrassed to tellit. But eventually Pol Pot and theKhmer Rouge atrocities drove himaway from Marxism, from the moraland political philosophy he’d chosento guide his life. “It is wrong for humanbeings to define all the terms of theirown existence,” he says, “and to think,therefore, that what they see as legitimatemeans to their goals are, in fact,legitimate. There are some things thatyou just don’t do.”He learned something, and hechanged. “Marxist radicalism waswhat my life led up to and away from,”he says. “I’m surprised now to seehow short a period that was in my life,but it was pivotal.”Marxism in the killing fields hadlost its moral compass, and as aresult, Richie Schuldenfrei startedlooking for boundaries, for solid linesthat defined what was right and whatwas wrong. The question—“How doSchuldenfrei says he is not a philosopher—hejust teaches philosophy. Ofhis students, he says, “I want to teachthem something that they can takeaway with them ... that’s going tomake a difference in their lives, notjust a little patch of knowledge thatthey’ll never have any reason to bringup to live memory in the future.”you live a good life?”—had changedfrom a political one to an ethical andmoral one. He discovered Judaism.Raised in a “vigorously unobservant,wholly Jewish community” in Brooklyn,Richie went to Hebrew schoolfour days a week when he was ingrade school. But still, when he left forcollege, the religious aspects ofJudaism weren’t a part of him. “I waslike a fish in water—I didn’t know thatI was wet,” he says of his Jewishness.Now, reflecting back, Richie thinks hemay have stumbled into philosophybecause he was looking for guidancethat he hadn’t realized through religiousstudy.“I see now that I inherited this Jewishtheoretical concern with livingright. Philosophy is my version ofbeing a yeshiva bochur—a young boywho spends his time studying Talmud.That’s the real impetus for me inphilosophy—the search for what Jewishstudents were looking for generationsago by studying the Talmud.”As a young professor at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>,Richie had a reputation forthrowing things. He would scream andjump on desks and whack kids on thehead with newspapers. Susan PerkinsWeston ’81, now executive director ofthe Kentucky Association of SchoolCouncils, tells a story that’s become aSchuldenfrei classic. Her class wasdiscussing a moral issue when onestudent made the mistake of tellingRichie he couldn’t prove what he wassaying. Richie held a chair over thestudent’s head and asked, “Can yousay, without a doubt, that if I let thisgo, it will fall?” The student said, “No.”And Richie asked, “Do you think thatyou have enough information to inferthat it might fall?” The student said,“Yes.” And Richie asked, “Do you haveenough information to have a strongconviction about what’s going to happen?”And the student said, “Yes.”Weston calls them “Richie Stories.”Her classmate, Maria Eddy TjeltveitJUNE <strong>1998</strong> 11

’81, now an Episcopal priest in NewJersey, recalls running into Richiewhen she was test-driving a car. “Hetold me, ‘The only way to lose tenureat <strong>Swarthmore</strong> is to buy a large American-madestation wagon,’” she says.Noah Efron remembers his first day ofphilosophy class his freshman year.“Some guy in the class started spoutingoff—‘Dialectical’ this, ‘dialectical’that—and Richie said, ‘Dialectical?You can’t use that word any more thissemester. I’ve been studying philosophyfor 20 years, and I don’t knowexactly what that word means, so youcan’t possibly understand it enoughto use it.’”Even now, when Weston and her<strong>Swarthmore</strong> friends get together, theytalk Richie-isms. Richie on television:“Television is caged fire, and we’resupposed to sit around and watch thefire.” Richie on capitalism: “Sara Leepound cake and Wishbone dressingare the greatest accomplishments ofcapitalism.”“I always tell about the time Richiethrew an Alasdair MacIntyre bookacross the room at me. I’m sure he’sstopped beating his students,” Westonjokes. “He has to have calmeddown some.”These days Richie doesn’t feel theneed to inject such enthusiasm orenergy into his classes artificially.That doesn’t mean he’s stopped beingenthusiastic or energetic; he’s just notas apt to throw a copy of Plato at thewall. “When I started teaching Plato, Ithought his arguments were so weak,so uninteresting, that I started beefinghim up. ‘Maybe he means this.’‘Maybe he means that.’ Then one day Irealized that all this stuff I thought I’dinvented was actually there. It was somuch more complicated than I everimagined, and it did things that Ididn’t know you could do in philosophy.”Richie is comfortable with Platonow, comfortable with all of the theorieshe teaches. And, because of it, heenjoys philosophy more—so much sothat he thinks this past semester washis best in 30 years.“He’s not all angst anymore,” saysEfron, who’s kept in close contactwith Richie over the years. “But thepyrotechnics weren’t what was important.There was something profoundbehind it all. He may scream less andthrow things less, but I’m sure hiseffect is quite the same.”The effect may be, but Richie himselfis clearly not the same personhe was in 1966. He’s married now toHelen Plotkin ’77. He has 7- and 11-year-old daughters. At 56, he’s morerespectful of traditions, of family, ofreligion. And he’s more conservative.In that sense the new Richiedoesn’t quite fit in with the schoolthat <strong>Swarthmore</strong> is today. But then,he didn’t entirely fit in back in 1966either. “I thought that I was pretty instep with ’60s politics when I got toMarxism inthe killingfields had lost itsmoral compass,and Schuldenfreistarted lookingfor boundaries.He found Judaism.<strong>Swarthmore</strong>, and the <strong>College</strong> wasn’t.But then those politics became themainstream and ‘won’ over the <strong>College</strong>.You could smell the egalitarianismin the air.” As the institution grewmore liberal, Richie started movingaway from what he calls the “radicaledge.”“Later came this frenzy of politicalcorrectness,” he says. “I’d seen it coming,but I wasn’t prepared for howextreme it became. Deconstructionism.Multiculturalism—it was so exaggerated.But that energy is sort ofgone now. The extreme has passed.”In effect Richie and <strong>Swarthmore</strong>switched places. “We’ve both changeda lot.”But in one fundamental way, RichieSchuldenfrei is <strong>Swarthmore</strong>. And<strong>Swarthmore</strong> is Richie Schuldenfrei.Both believe in liberal education. Bothexist to challenge students to think oflife in all of its moral dimensions. Bothwant young people to see the connectionsbetween what they learn andwho they are and how they act in theworld.“In class yesterday a student askedme what he should write when he’swriting about Hume—‘Hume argued’or ‘Hume argues?’ I said, ‘Humeargues.’ I want the kids to think ofHume as sort of there to argue withthem. I want Hume to represent aposition with which they can actuallyhave a discussion in their own heads.After they leave here, when they haveto ask themselves questions, whenthey make decisions in their lives, Iwant them to ask themselves, ‘Whatwould Kant say about this?’ ‘Whatwould Hume say about this?’ ‘Whatwould Aristotle say?’ I want to givethem the vocabulary to ask thesequestions.”“Richie gave me a set of gnawing,serious, fundamental questions—neuroses,more—that has moved me eversince,” says Efron. “What does it meanto live a good life? How do you knowwhat sorts of things you’re supposedto know? I think of those questionsevery day when I open The New YorkTimes or look at my daughter or findmyself at synagogue.”However, Richie sees the dark sideof the personal nature of his teaching.He once read a letter from a studentthat said, “My whole education waswrecked by that asshole Schuldenfreiwho let his personal problems interferewith his teaching.”“There are some people out therewho I didn’t do well by because Icouldn’t take a detached academicstance. I don’t disapprove of that kindof teaching, I just can’t do it. And I feellike I owe apologies to all the studentsI’ve taught who have been hurt by mypersonal style.” Most often, Richiesays, he can’t live up to the high standardshe teaches in class. “Personally,I’m more like Woody Allen than JohnWayne.”Either way, Richie doesn’t give hiskids rules or instructions. He doesn’tgive them complete scholarship orscientific theory. He doesn’t give themsolutions to particular moral dilemmas.He certainly doesn’t give themanswers. What they leave with aretheories, mirrors, means to isolatedimensions of moral life and holdtheir lives up to them. He gives hisstudents something that’s going tomake a difference in their lives.Today, on this rainy Thursday afternoonin 324 Papazian, the subjectis vices, Ordinary Vices, a book by contemporaryphilosopher Judith Shklarwhich offers a new approach to beingmoral. Already, the class has flushedout Shklar’s theory—that people must12 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DENG-JENG LEEAs <strong>Swarthmore</strong> became more liberal,Schuldenfrei saw himself moving awayfrom what he calls the “radical edge.”learn to live with commonplace vices,such as hypocrisy, snobbery, betrayal,and misanthropy. Eradicating theminevitably leads to a much worsevice—cruelty, especially mass socialand political cruelty, Nazism, Stalinism,and the like. Shklar puts crueltyfirst and tells us not to be so afraid ofthe other vices, which can’t be avoidedin the modern world.Richie wants to know if the classthinks she’s right. Is avoiding crueltythe goal of a good life? Is cruelty theultimate vice? What about betrayal?What about Chapter 4, “The Ambiguitiesof Betrayal?”“It’s impossible not to betray,” saysthe student with the sandwich. Richielets this comment hang as he sitsdown in a chair and throws his armover the back of it, crossing his legs.The drama is there; it’s just subtlerthan it used to be.“Is it, then, impossible to be loyal?”Richie asks, his Bronx accent as thickas an East Village cab driver’s.One student sitting under the windowin the back of the classroom isn’tsure if it’s a good thing to live withbetrayal but also isn’t sure how to livewithout it. He wishes Shklar weremore clear-cut. “She uses marriage asan example,” he says. Richie standsup and puts his hands on his hips.He’s finished warming up now. He’sready to roll. “Infidelity and divorcemay look like a betrayal,” the studentcontinues, “but if a person is unhappyand decides to stay in a marriage, isn’tthat person betraying himself?”“Well,” answers Richie. “She’s obviouslynot advocating the Liz Taylorapproach to this problem, but she’salso not advocating the CatholicChurch’s. Hmmmm ... let’s see. Whatwas the title of this chapter? ‘TheAnnals of Betrayal?’ Noooo. ‘The Disasterof Betrayal?’ Noooo. Wasn’t it,‘The Ambiguities of Betrayal.’ Right?”Everyone laughs. The guy sittingnext to the student leans over andwhispers, “He got you that time.”A Richie story, no doubt. ■Vicki Glembocki is a writer based inState <strong>College</strong>, Pa. She is associate editorof The Penn Stater magazine.13

A personal account of coming out at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.It is March <strong>1998</strong>, and I am sitting in a building onthe <strong>Swarthmore</strong> campus—the Lang PerformingArts Center—that didn’t exist when I was here inthe 1980s. I am back for the first time in 13 years,invited to speak at the Sager Symposium’s 10thanniversary—an event that didn’t exist when I washere—about coming out at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.I scan the room and note that the students todaylook not so different from the way we looked, exceptfor the trend toward shaven heads and nose rings. Butsitting in front of me is something I never experiencedat <strong>Swarthmore</strong>. It is a son sitting next to his father—unmistakably related by the same bend of theneck, sweep of the hair, tilt of the head. It is Parents’Weekend, and this father has accompaniedhis son to a seminar on being queerat <strong>Swarthmore</strong>. I wonder if my fatherwould have come to such a lecture whenI was a freshman, had anything likethis even occurred 17 years ago.In the years since I left college,lesbians and gays have been onthe cover of News-week; havehad a popular televisionshow; have died of AIDSand started a nationalhealth campaigntopreventtheHomeistheSpiritBy Laura Markowitz ’85spread of HIV; have been addressed by a sitting president;and have come out in every walk of life, includingthe foreign service, military, academia, and entertainmentindustry. Some of the queer students at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>today were “out” for more than five years beforethey came to college; are already mentors for otherqueer youth; went to their high school proms withsame-sex partners; speak easily about parents, brothers,and sisters who are queer. <strong>Swarthmore</strong> has thenewly endowed James C. Hormel Professorship inSocial Justice, thanks to James Hormel ’55, a gay manwho serves on the <strong>College</strong>’s Board of Managers. [Seepage 43 for more on Hormel.]<strong>Swarthmore</strong> also has the longest-standing queersymposium on any college campus, ever, anywhere.What’s clear to me, as I survey the crowd at the 10thanniversarySager Symposium, is that queers have“arrived” at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.Icame out for good in 1984, during my junior year ofcollege. A close friend who came out around thesame time I did recently remarked on how beinggay means spending your entire life coming out. “It’s aprocess that never ends,” he said. “You make newfriends, change jobs, move house, meet family membersand all of these events typically require us tocome out anew. I think how you come out changes,how you feel about coming out changes, your desire tocome out or not changes with time.”I had started to come out on my first day of college,to a new friend I met in the hallways of Willets—inthose days the rowdy, party dorm for freshmen. Thisnew friend and I went for a walk and tried to analyzewhat faux pas we had made on our housing form to beassigned to Willets. Eventually, we talked about ourhigh school boyfriends and then she said she thoughtshe might be a lesbian, and I said out loud, for the firsttime, “I know I am.”I was astonished at myself for having said outloud what had been terrifying to acknowledge tomyself. I was 17, and I had nowhere to put this informationabout myself. The fact was, I had neverknown an “out” lesbian before. I wasn’t sure what itmeant to be one, apart from the obvious attractionto women. But I did know it wasn’t safeto be out. In this, my experience as ayoung lesbian was much the same as itis for queer youth today. A recent surveyof 2,000 gay, lesbian, and bisexualyouth ages 10 to 25 shows thatmost take three years to come outto someone else.SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

Laura Markowitz ’85 gave thekeynote address at this year’s10th-anniversary Sager Symposium.This essay is adaptedfrom her speech.The next week, I met my first real,live lesbian. My roommate and I,both feminists, were planning ongoing to a meeting of the Alice PaulWomen’s Center, but herboyfriend—a worldly sophomore—warned us that “it was full of lesbians.”Of course then I really wantedto go. I spent the whole time at themeeting trying to figure out who was alesbian.There was one woman—a senior—who dressed in black and wrote poetry,so I figured she must be the lesbian. Iwatched her from afar, trying to figureout what a lesbian was like. I heardthat some guys on her hall had sether door on fire, that they had spraypainted“Kill the Dyke” on the walloutside her room. I heard peopleshouting humiliating commentsabout her when she walked throughSharples Dining Hall. I promptly started datingmen. I didn’t consider my relationships withmen those first two years at college a “lie” becausethere was genuine affection. But I wrote in my journalat the time, “It is as if I am waiting for something,maybe a new language, so I can tell myself the realstory about who I am.”Unbeknownst to me at the time, I was often in thecompany of lesbians in the form of my teammates. Iplayed a sport, and there was, I later learned, a tightknitgroup of women on the team who were lovers withone another. They were not political feminist lesbians.They avoided the Gay and Lesbian Union (GLU) likethe plague. Maybe they didn’t even call themselves lesbians.When a classmate matter-of-factly told me thattwo women on our team were lovers, I was fascinatedby this first lesbian couple I had ever known of, and Iobserved the way they kept their affection for eachother hidden. I never stopped to wonder why. It wasobvious: They were surviving. They didn’t want theirdoors spray-painted. They didn’t want the nasty commentsand stares.There was another, similar type of lesbian at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>in the early 1980s, I later discovered. These werewomenfriends whowere havingintensely intimate andsexual relationships with each other, but theynever told anyone. Some even had serious romanticinvolvements with men as well as having womenlovers. When I finally came out publicly, it wasn’tuncommon for one or both in such a couple to seekme out and confess their secret affair. I could understandtheir reluctance to come out. How intrusive tohave to declare something so sexual and private to theworld, yet how difficult it was for them to hide their©<strong>1998</strong> MARTY KATZJUNE <strong>1998</strong> 15

omance and endure their friends’suspicious speculation.Almost every single one of thesewomen is now married to a man andhas children. We didn’t use the word“bisexual” back then, but perhapsthey were bisexual. There seemed tobe two choices back in the early1980s: straight or lesbian. (My junioryear, just back from Asia where I hadbecome an ardent meditator, I founda convenient third option: spiritualcelibacy.) Before I graduated someonedid start the Bisexual and QuestioningCircle, but many people—myself included—figured “bisexual”meant “too scared to come out allthe way.” Many of us—straight andqueer—still have trouble fittingbisexuality into our dichotomousview of sexuality.There was no language for what Ifelt about myself as a lesbian.Saying the word “lesbian”didn’t resonate with me because I had no clear imageof what a lesbian was, what a lesbian life would looklike. I admired from afar a student a few years behindme who had come out during high school—how hadshe survived? I couldn’t imagine it. I had never met anout, adult lesbian. There was not a single one that Iever knew of at <strong>Swarthmore</strong> during all the years Iattended. I didn’t know that there were lesbian professorsat <strong>Swarthmore</strong>, although we all knew of a few gayprofessors—it seemed safer for men in academia tocome out, but double jeopardy for women. Those werethe days when we fought to get Women’s Studiescourses on campus, and all feminists were suspectedof being lesbians.My years at <strong>Swarthmore</strong> before coming out wereneither tortured nor unhappy. This may be because Icould pass for straight. My gender presentation was“normal” feminine, no one walked behind me andyelled, “bulldagger” or called me “sir” by mistake. I hada friend a few years older who, before and after shecame out, spent a lot of time asking us if we thoughtshe was “too butch.”Despite being closeted and confused, if you hadasked me what I thought of <strong>Swarthmore</strong> my first twoyears there, I would have told you I loved it, and Iwould have meant it. I loved being with my friends,feeling intellectually awake, and finding my niche in thecommunity. For the first time in a long time—afteryears of living at home with my mother’s illness anddeath and my family’s disintegration—I wasn’t lonely. IIwas filledwith my ownfears andstereotypes ofbeing queer....Not only was Iunable to feel athome in myself,there werecrucial ways inwhich I couldn’tfeel at home at<strong>Swarthmore</strong>.was happy, but I survived by periodicallyforgetting I was a lesbian. I survivedby never allowing myself tohave a single crush on any woman. Isurvived by forgetting I had used theword “lesbian” to describe myself, asif I had never known it and, in notknowing it, could not be it. I washappy, true, but I was also shut offfrom myself.Shutting ourselves off, editing ourselvesso we can pass, is one of thepsychological effects of oppression.Even though I wasn’t out yet, I wasfilled with my own fears and stereotypesof being queer and intimidatedby the casual undercurrents ofantiqueer sentiment all around me,in a population of teenagers andyoung 20-year-olds. Not only was Iunable to feel at home in myself,there were crucial ways in which Icouldn’t feel at home at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.“Home isn’t just a place to sleepand hang your clothes,” wrote familytherapist Kenneth Hardy in an issue of my magazine, Inthe Family. “It is also a state of being, a sense of intrinsicallyfitting in to the community around you andbeing welcomed, invited, accepted, and free to be complete.”All of us long for a sense of place, of belonging,and in the peer world of college, the need to fit in andbe accepted is even more intense. When I finally cameout to my friends, I found them unsurprised, supportive,and loving. In this, I was lucky. Many queers hadthe opposite experience.The psychological wound caused by homophobia isa kind of emotional homelessness. Hardy writes, “Lesbiansand gays can’t operate in the world with a basictrust in life’s fairness, nor can they ever assume theywill be regarded as full human beings by other membersof society.” During my senior year, the GLU wasbattling the Admissions Office because the informationabout GLU had deliberately been left out of the materialson clubs and activities sent to prospective students.They didn’t want to scare anyone, the admissionspeople told us. Parents of prospective studentsmight not want their kids going to a college thatseemed to support queers. The <strong>College</strong> apparentlywasn’t worrying about the message it was sendingthose isolated, scared, queer prospective studentsthrough this deafening silence.Such silences taught me implicitly what Hardy calls“learned voicelessness,” a process by which I came tounderstand that I was not entitled to say who I was,what I knew, or what I experienced. When I fell in love16 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

with a woman and really let myself feel it, I was terrified.I went to the counseling center to talk about it.The young counselor—probably a graduate intern—heard me say I thought I might be a lesbian, and herresponse was, “Did you ever think you might not be?”Then she changed the subject.Learned voicelessness is the “Don’t ask, don’t tell”policy in many families. The utter silence in my familyabout homosexuality was a lesson of omission. Likemost parents, my father wasn’t glad to hear that I wasa lesbian. But when I came out to my father during winterbreak of my senior year, I didn’t expect him to beupset. We had always seen eye to eye on things, and Iwas in love, happy, and relieved that I had finallyaccepted this information about myself. I somehowwasn’t prepared for his ashen look, as if I had told himI had cancer. He wouldn’t speak a word. Hugging himin the kitchen, I could hear his heart beating, and Icould feel his breath rising and falling. Time stoppedfor us both. I asked him to say something, and hecould only tell me, “I don’t want to say the wrongthing.”Always close, particularly since my mother haddied, we were very careful with each other for the nexttwo years. I knew he wouldn’t cut me off because heloved me. I was his child, and it would have been asinconceivable for him to cut me off as it would havebeen for him to amputate his own arm. But I felt that totalk about my lesbianism would drive us further apart,and so I colluded in the silence. I stopped telling himanything about my life. My sister, on the other hand,always helpful, sent him books like So Now You Know.Although he was struggling with what it meant tohave a lesbian child, my father was perfectly pleasantand welcoming to my lover, as he was to all myfriends. He occasionally asked if this or that onewas gay, and he was pleased, I could tell, that notall my friends were queer. I think he still heldout hope that I would grow out of this “phase,”and the fact that my best friend was a heterosexualman helped him feel that I hadn’tjoined some sort of man-hating cult.I’m sure it’s difficult for parents to figureout why their child happens to bequeer. After I came out to him, myfather ran into an acquaintance whoseson had graduated from <strong>Swarthmore</strong>several years before I arrived. Mydad asked him what he thoughtabout the <strong>College</strong>, and theman—whose son, it turns out,is gay—growled, “It’s full oflousy homosexuals!” Myfather remembered thatconversation, and during one of our frustratingattempts at talking about my lesbianism, he related itto me and suggested that <strong>Swarthmore</strong> was to blame. Itold him, if it was, then please send the <strong>College</strong> a bigcontribution because I was very happy about being alesbian. This surprised him, I think. What he was seeingas a tragedy, I regarded as a great relief and blessing.It took us many years to reconcile our differentviews of my lesbianism. Just as I had never hadany role models of adult lesbians, neitherhad he.Although I didn’t have any direct experiencesof harassment while I was a student,I saw other gays, lesbians, and bisexualsbeing harassed and threatened. Someoneleft a half-dissected lab animal onthe library carrel of a lesbian friendof mine. Unfortunately, episodeslike these still happen at<strong>Swarthmore</strong>. At the SagerSymposium I was toldthat there were severalantiqueer incidentson campus this year.The Sager Fund —“a sense of belonging”In an effort to combat homophobia and related discrimination,sculptor Richard Sager ’74, a leader inSan Diego’s gay community, established a fund at the<strong>College</strong> in his name in 1988.The fund, administered by a committee of womenand men from the student body, alumni, staff, faculty,and administration, sponsors events that focus onconcerns of the lesbian, bisexual, and gay communities.It also promotes curricular innovation in thefield of lesbian and gay studies and supports theannual Sager Symposium.“One of the wonderful outgrowths of the fund,”Sager said recently, “is that it has created a sense ofbelonging for lesbians and gay men who graduated10, 20, or 30 years ago.” The focus of this year’s 10thanniversarysymposium was on those alumni, whodiscussed their experiences of activism on campusand living as open homosexuals after graduation.In the last 10 years, the symposium has presentedtopics including “Screen Tests: Experimental Identitiesand New Queer Media,” “Queer the Institution/Institutionalize the Queer,” “Coalitions Across QueerDifferences,” and “Social Policy and Activism.”The Sager Fund continues to grow through contributionsmade by Richard Sager and by alumni andfriends of the <strong>College</strong>.JUNE <strong>1998</strong>

I spoke with students who feel bitter and disillusionedby the fact that <strong>Swarthmore</strong>, which has a reputationfor being open and accepting of queers, is not a completelysafe place for them. Their complaint was notthat the hate crimes happened, but that the administrationdidn’t take any action beyond a statement officiallycondemning the harassment.I worry that the conditions of learned voicelessnessand psychological homelessness are being replicatedhere today, right now, because, as students report, theincidents get muffled, and they feel that no oneaddresses their eroding sense of safety. Are we sayingto these students, “Look, now, no one was hurt, sodon’t make a fuss. You’re at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>! Don’t youknow how good you have it?"After graduation I left for a year on a Watson Fellowship.My father still hadn’t told a soul, noteven my stepmother, that I was a lesbian. Hehardly wrote to me, and when he did, he didn’t saymuch except that he loved and missed me. I missedhim, too. It was strange to feel so viscerally connectedto him yet so unable to speak about what was reallygoing on between us. I was grateful in a way for hissilence while he grappled with his ambivalencebecause I knew how different it could have been. I hadqueer friends whose parents had cut them off,screamed insults at them, kicked them out of thehouse. My father’s biggest worry was that the worldwould be unsafe for me. At one point, I told him, “I canhandle the rest of the world’s problem with it; it’s yourdisapproval that’s hard for me.” He heard that, and theair between us began to lighten.When I finally returned home, I moved to Washington,D.C., and shared an apartment with a good friendfrom <strong>Swarthmore</strong> who was gay. We were both scaredabout being out in the adult world. He had friends whowere dying or dead from AIDS. We went to a gay/lesbianbar for about 20 minutes and then fled. Neither ofus had come out at our jobs, but we regaled eachother with stories of who might or might not be gay atthe office. It took a toll on me, not coming out at work. Ifound it impossible to have genuine friendships withmy co-workers because I was keeping this big secret,Why “Queer”?In April 1997, In the Family, the magazineI publish, ran a special issueabout straight allies of lesbians, gays,and bisexuals. The cover line read:“What Makes Straights Wave theQueer Banner?” Soon I received a callfrom an angry lesbian subscriber.“How could you print that terribleword ‘queer’ on the cover of yourmagazine?” she asked me.Language and labels are deeplypoliticized—and also deeply personal.Although the word “queer” has beenused to humiliate and degrade homosexualsin earlier generations, thesedays “queer” is the new, all-inclusiveterm for anyone who doesn’t identifyhimself or herself as heterosexual.Queer theory has become a cuttingedgeacademic pursuit encompassingquestions of gender, sexual orientation,and culture. While older lesbiansand gays who remember the daysbefore gay liberation recall how“queer” was hurled at them as aninsult, many younger people preferthe term “queer” because it is openendedand doesn’t rigidly describeany specific sexual orientation. Itleaves room for ambiguity, which isalso a kind of privacy.The names of campus groups overthe years reflect a changing consciousness—notonly of of how lesbians,gays, and bisexuals presentthemselves but of the changing campusclimate. The appearance of theword “lesbian,” the inclusion of“bisexuality,” the involvement ofstraight allies, and finally the generaluse of the word “queer,” are markersof the movement’s history at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.The following list of campusgroups was compiled through aninformal survey of alumni and studentsat the recent Sager Symposium.1970s: Gay LiberationEarly 1980s: Gay and Lesbian Union(GLU)Mid-1980s: Bisexual and QuestioningCircle (BQC)1986: Merger of GLU/BQC1989: Alternative Sexualities Integratedat <strong>Swarthmore</strong> (AS IS)1991: Action Lesbigay1992: Lesbian Bisexual Gay Alliance(LBGA)1992: Association for Sexual OrientationRights and Awareness(ASORA), composed mainly ofstraight allies1993: Fluid Women1995: <strong>Swarthmore</strong> Queer Union(SQU)1996: Our Glass (previously FluidWomen)1997: Queer Straight Alliance (QSA)When you get into the tangle oflabels and identity, there is always thequestion of who is allowed to callwhom what. For instance, manyAfrican Americans are offended whenblack comedian Chris Rock uses theword “nigger.” Lesbians may refer tothemselves as “dykes,” but is it OK if astraight person uses that term? Contextis everything. When a gay friendof mine calls himself a “queen” or a“fag,” it doesn’t mean he would feelcomfortable if a straight person calledhim that. For years lesbian feministsprotested that calling them “gay” wasas sexist as referring to all humans as“men.” At the same time, some gaywomen can’t relate to the word “lesbian.”When Ellen DeGeneres wasinterviewed by Diane Sawyer, she saidthat the word “lesbian” sounded like adisease, but a few months later shewas calling herself a lesbian.As a writer and editor, I appreciatethe economy of “queer”—imaginehaving to find fresh ways to say “lesbian,gay, bisexual, transgendered,and questioning” at least twice a paragraph.—L.M.18SWARTHMORE COL-LEGE BULLETIN

ut I also didn’t feel safe coming out.I worked at a typical nonprofit thinktank, mismanaged by a charismaticjournalist and his two sidekicks, oneof whom made inappropriate, sexuallyexplicit passes at all of us youngfemale interns. I quit within sixmonths in protest, and a half-dozenof my colleagues followed. I felt thatif I had come out, I would have lostcredibility—I would have beenlabeled a “man-hating dyke” and mycomplaints about the harassmentminimized or dismissed.It was scary being out in the “realworld,” and because of that I am nolonger startled by the number of lesbiansI knew in college who are nowmarried to men. I wish them all well,but it is always hard to hear aboutyet another “has-bian.” What does itmean about lesbianism, about thestress of being queer? Was it just thatthey had been “experimenting” incollege, where it was reasonablysafe, but once they got into the realworld they didn’t want the struggle?At <strong>Swarthmore</strong>, I had not felt menaced,and I took for granted that it would always feelthis way to be a lesbian in the world. I hadn’t yet realizedhow fortunate I had been to come out in a relativelysafe, accepting environment, and how privileged Iwas to be white, middle class, and educated. All ofthese things rendered me more acceptable in the mainstreamand, therefore, cushioned me from some, butnot all, of the physical and emotional danger of comingout.When I took my second job as a staff editor for asmall magazine, I decided to come out from day one. Iwas the first and only lesbian almost everyone therehad ever met, but they got used to me, and I felt comfortableand happy there. After two years, I startedworking at the Family Therapy Networker, where I’vebeen for nine years or so, and I began writing aboutgays and lesbians in the family.A big turning point in my relationship with myfather was when I wrote about him in the Networker. Iwrote about the problems we had been having, andour inability to talk about my lesbianism. He loved thearticle and gave it to everyone he knew, and in thatway he finally came out to his world. When he brokethe silence, I could come home emotionally and psychologically.I could reconnect with my aunts, uncles,and cousins without the burden of having a secret. Icould talk openly and happily about my life and knowI graduatedwithout aclear sense ofwhether ornot I was anembarrassmentto the <strong>College</strong>.Until recentlyno one wascelebrating thegenerations ofqueer studentswho had madetheir mark onthe school andin the world.that my father wasn’t standingbehind me, flinching.For the past 11 years, my partner,Mary Kay, and I have become eachother’s family and have asked ourfamilies, insurance company, neighbors,and friends to treat us like afamily. My brother and sister putMary Kay’s picture next to mine ontheir refrigerators so their childrenrecognize both their aunts. Mycousins ask us when we’re going tohave a wedding. Mary Kay’s fathergoes out of his way to include me ininvitations for family holidays. Whenwe wanted to take a romantic tropicalvacation but worried whether itwould be dangerous to be openlyaffectionate in those heterosexualmeat markets, my parents offered tocome along to protect us, and sureenough, they followed us down thebeach while we held hands, watchingour backs.Until the Sager Symposium invitationsstarted coming in the mail, Inever knew where, exactly, my placewas as a queer alum of <strong>Swarthmore</strong>. Igraduated without a clear sense of whether or not Iwas an embarrassment to the <strong>College</strong>. Until recentlyno one was celebrating the generations of queer studentswho had made their mark on the school and inthe world.If home is the spirit we hope to find in others, anend to being pushed out in the cold because of somedifference that is deemed unacceptable, then I feel Ihave finally come home to <strong>Swarthmore</strong>. I hope thescores of queer alumni out there—many of whomcame out after graduation, some of whom are comingout at midlife and older age—can also come home. ■Laura Markowitz ’85, majored in religion at <strong>Swarthmore</strong>and is senior editor of Family Therapy Networker, amagazine for psychotherapists. Winner of a NationalMagazine Award for writing, she is a freelance writer forUtne Reader, Glamour, Ms., and other publications. In1995 Markowitz launched In the Family, a magazine forlesbians, gays, bisexuals, and their relations, whichreceived the 1997 Excellence in the Media Award. Forsubscription information, write In the Family, P.O. Box5387, Takoma Park MD 20913.<strong>Swarthmore</strong> alumni who would like to know moreabout future Sager Symposia may be placed on a mailinglist by writing to Chair, Sager Committee, <strong>Swarthmore</strong><strong>College</strong>, 500 <strong>College</strong> Avenue, <strong>Swarthmore</strong> PA 19081-1397.JUNE <strong>1998</strong> 19

Why can’t a college beAs <strong>Swarthmore</strong>’s comprehensive fee breaksBy Jeffrey LottMabel Clement Lee ’34 still hasone of her <strong>Swarthmore</strong> <strong>College</strong>invoices, dated “NinthMonth, 8, 1933.” In an era ofcomputer-generated bills, its typewrittencharacters have the look of amedieval manuscript. Yet puttingaside the quaint Quaker nomenclaturefor September, the real curiosity is thefull price of Lee’s senior year at college.Including room, board, and aspending account deposit, it came to$950.In August <strong>Swarthmore</strong> will mailinvoices for the <strong>1998</strong>–99 academicyear. The bottom line for those payingfull price: $30,740. But then, not everyonepays full price, and every studentat <strong>Swarthmore</strong>—including those whopay $30,740—receives a significantsubsidy from the <strong>College</strong>’s endowment.“Price” is the key word here, saysPaul Aslanian, vice president forfinance and planning, and it is quitedifferent from “cost.” Next year the<strong>College</strong>’s actual expenditure per student—thecost of a <strong>Swarthmore</strong> education—willbe approximately $51,000.Thus the <strong>College</strong> will subsidize theeducation of every enrolled student,whether or not that student receivesfinancial aid, with about $20,000 infunds from sources other than tuitionand fees. Significantly, this figure doesnot include the funds set aside fromthe budget for outright grants to aidedstudents. It is pure “value added” forevery <strong>Swarthmore</strong> student, and itcomes largely from endowmentincome and to a lesser extent fromother annual gifts.Still, the price of quality higher educationis perceived as being steep,and Aslanian is often asked why the<strong>College</strong> can’t be run more like a busi-20 SWARTHMORE COLLEGE BULLETIN

ILLUSTRATIONS BY SHERRI JOHNSONmore like a business?the $30,000 barrier, it’s a good question.ness. The implication of the question,he says, is that “if you guys could runa tighter ship, college wouldn’t cost somuch.” He argues that wherever possible,<strong>Swarthmore</strong> does run a tightship, but there are significant economicdifferences between a for-profit corporationand an institution of higherlearning—especially a first-rank collegelike <strong>Swarthmore</strong>.Aslanian, a former economics professorwho was treasurer of Macalester<strong>College</strong> before coming to <strong>Swarthmore</strong>in 1996, points to two fundamentaldistinctions: the inability to substitutecapital for labor, as has occurredin business, and the <strong>College</strong>’s desireto stay small, which places limits onfaculty productivity.“If you were to look at a manufacturingplant, the way people are doingbusiness in <strong>1998</strong> is significantly differentfrom the way it was done in 1963,”explains Aslanian. “Technology andnew machinery have hugely increasedthe output per worker and consequentlymade the factory more efficient.This phenomenon has morerecently been extended to white-collarjobs in many industries.“Now look at the underlying economicsof how a <strong>Swarthmore</strong> facultymember teaches a class in <strong>1998</strong> versus1963. You may see a difference inteaching style, but at the end of theday, he or she has taught just aboutthe same number of students as 35years ago.“We’ve made the choice, based onour understanding of what constitutesthe highest-quality undergraduateexperience, to have small classes, personalinteraction between faculty andstudents, and collaborative researchopportunities at the undergraduatelevel.” At just under 9:1, <strong>Swarthmore</strong>’sstudent-faculty ratio is among the lowestin the nation.JUNE <strong>1998</strong> 21