SWARTHMORE

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2000) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2000) - ITS

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>C O L L E G E B U L L E T I N S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0D I S T U R B I N GT H E P E A C EO F R A C I S M

<strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0F e a t u r e sF r o m t h e B a r d t o B e l o v e d 1 2Why the English curriculum is always changingBy Tom KrattenmakerD i s t u r b i n g t h e P e a c e o f R a c i s m 1 6Kathryn Morgan’s story—in her own wordsBy Laura Markowitz ’85C a t h e d r a l s , C a s i n o s ,& C u l t u r a l C o n t e x t 2 4Learning from what you hate,with architect Steve Izenour ’62By Bill KentS w a r t h m o r i s m s 3 0A lexicon of Swarthmorelanguage through the ages16By Andrea HammerON THE COVER:KATHRYN MORGAN WAS <strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>’S FIRSTAFRICAN-AMERICAN PROFESSOR. AFTER NEARLYA DECADE OF RETIREMENT, SHE SPEAKS ABOUTHER STRUGGLES AND JOYS AT <strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>.PHOTOGRAPH BY JIM GRAHAM.3024

DepartmentsL e t t e r s 3Our “No Smoking” sectionC o l l e c t i o n 4Campus and CommencementA l u m n i D i g e s t 3 2A new alumni director and more12C l a s s N o t e s 3 4See anyone you know?D e a t h s 4 3Swarthmore remembersA l u m n iP r o f i l e sC o s m i c C o n c e r n 4 1Richard Setlow ’41 radiatesexpertise.By Andrea Juncos ’01O n B r o a d w a y 5 8Jessica Winer ’84 paints theGreat White Way.By Audree PennerW a l k i n g f o rP e a c e 6 6Crispin Clarke ’98 seeksharmony with the Earth.By Jeffrey Lott472Books & Authors 52Stop bowling, and read a bookI n M y L i f e 6 4Learning to pack lightlyBy Kirsten Schwind ’96Our Back Pages 72Han-Chung Meng’s wartime journey64

P A R L O R T A L KS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NRegular readers of this column stop here to learn something about thecurrent issue of the Bulletin, but I suspect that a few of you may bereading “Parlor Talk” for the first time, searching for a clue as to whathappened to your magazine. It looks different, doesn’t it? Our new designer,Suzanne DeMott Gaadt, has done some serious renovations.A magazine designer arranges words and images to invite you into ourpages and deepen your understanding of our articles. Good design ismore than decoration; it complements and enriches the ideas and storiesthat are the heart of this magazine. Yet, until a magazine’s readers noticea change, they may not ever consider how carefully it’s done.In colleges as with magazines, change is something we notice. Whenalumni return to Swarthmore, they comment more frequently on the newthan the familiar—new buildings, new faculty members, a more diversestudent body, new areas of study. AllIn colleges as with are examples of the constant, measuredchange that takes place in themagazines, change islife of a thriving, forward-looking college.Society doesn’t stand still, andsomething we notice.neither does knowledge; thus, Swarthmoreisn’t the same college it was in ...Swarthmore isn’twell, you pick the year.the same college itSeveral articles in this issue areabout change. Tom Krattenmakerwas in ... well,writes about new ideas and authors inyou pick the year. the English literature curriculum.Kathryn Morgan, professor emerita ofhistory, speaks her mind about the changes she’s witnessed—andwrought—in the racial consciousness of the College. Throughout thesepages, you will find dozens of examples of how Swarthmore students, facultymembers, and alumni are agents of change.Yet there’s one important transformation you might overlook becauseoutwardly it appears to be the same each year—Commencement. To me,this ceremony is the ultimate symbol of change because it celebrateshundreds of young people whose lives have been altered by the experienceof Swarthmore College and who will go on, in one way or another, tochange the world.That’s the design of a great college. In the scheme of things, a littlechange in the Swarthmore College Bulletin doesn’t seem like much, does it?—Jeffrey Lott<strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>COLLEGE BULLETINEditor: Jeffrey LottManaging Editor: Andrea HammerClass Notes Editor: Carol Brévart-DemmCollection Editor: Cathleen McCarthyStaff Writer: Alisa GiardinelliDesktop Publishing: Audree PennerDesigner: Suzanne DeMott GaadtIntern: Andrea Juncos ’01Editor Emerita:Maralyn Orbison Gillespie ’49Contacting Swarthmore CollegeCollege Operator: (610) 328-8000www.swarthmore.eduAdmissions: (610) 328-8300admissions@swarthmore.eduAlumni Relations: (610) 328-8402alumni@swarthmore.eduPublications: (610) 328-8568bulletin@swarthmore.eduRegistrar: (610) 328-8297registrar@swarthmore.eduWorld Wide Webwww.swarthmore.eduChanges of AddressSend address label alongwith new address to:Alumni Records OfficeSwarthmore College500 College AvenueSwarthmore PA 19081-1390Phone: (610) 328-8435. Or e-mail:alumnirecords@swarthmore.edu.The Swarthmore College Bulletin (ISSN0888-2126), of which this is volumeXCVIII, number 2, is published inAugust, September, December, March,and June by Swarthmore College, 500College Avenue, Swarthmore PA 19081-1390. Periodicals postage paid atSwarthmore PA and additional mailingoffices. Permit No. 0530-620. Postmaster:Send address changes to SwarthmoreCollege Bulletin, 500 College Avenue,Swarthmore PA 19081-1390.©2000 Swarthmore CollegePrinted in U.S.A. on recycled paper2

LAY OFF THE BEEFI was very sorry to read in the JuneBulletin about the fire at the IngleneukTea House.How many of you worked there? Icleared tables Tuesdays through Fridaysand made desserts on Saturdaysfor three memorable semesters during1952–53. In addition to lunch and ashare of the tips on days worked, wewere served dinner also as regularcustomers. If I chose not to eat dinner,I could take 75 cents in cash or, better,bring a guest on another day. Giventhe quality of College food in thoseyears, my guests appreciated theopportunity to enjoy dinner at theIngleneuk.There was one drawback. Often Iforgot to mention to my date ahead oftime that we had a $2 maximum fordinner. So, before we ordered, I had topeer over the top of the large menuand whisper, “Don’t order the roastbeef,” which costs $2.25.CHARLES “BUCK” JONES ’53McLean, Va.GRAMMAR, LOGIC,AND RHETORICProfessor [T. Kaori] Kitao’s article “TheUsefulness of Uselessness” (June Bulletin)is a sad and flawed attempt tojustify an anachronistic system of educationdevised centuries ago for anidle elite. It is sad because she seemsto feel the need to justify liberal artscourses as a method of improving students’ability to think and learn. AsProfessor Kitao indicates, such coursesare often intrinsically interesting.They need no further justification.The article is also flawed becausethere are far more efficient methods ofenhancing students’ ability to learn, tothink, and to be creative than studyingChaucer and hoping for a serendipitousmind-improvement by-product.Perhaps a return to the trivium ofgrammar, logic, and rhetoric should beconsidered by Swarthmore.RICHARD KIRSCHNER ’49Albuquerque, N.M.WORK ETHIC ISA SOCIAL CONSTRUCTI read with great interest the article onEmpowered Painters (“Collection,”June Bulletin). As Swarthmore graduatewho worked in Philadelphia’sKensington neighborhood for almosttwo years, I became acutely aware ofthe need for sustainable jobs for residents.Although I applaud the students’efforts, I was greatly disturbedwhen they implied that most of theworkers they employed from Kensington/NorthPhiladelphia did not havethe “right work ethic.”Work ethic is a social construct,and no one has any right to deem oneas the correct one. We need to examinepeople’s situations in the full contextof their lives, not judge them bymiddle- and upper-class values. Andany work ethic is difficult to buildwhen jobs are unavailable and do notpay a livable wage. Good, productivework with disempowered peopleneeds to be done not by judging thembut rather by trying to get a sense ofthe full context in which they live.As Swarthmore alumni, we are privileged.I would hope we use that privilegewith a true sense of social responsibility.Impoverished and disempoweredneighborhoods do not needmoralistic judgment. I do not think anyof us wants to resurrect the culture ofpoverty argument from years ago. Iapplaud the work Empowered Paintersis doing. I hope that the characterizationof people from the neighborhoodswhere the company works changes.JOANNE WEILL-GREENBERG ’96PhiladelphiaUNHEALTHY BEHAVIORI was surprised to see the poem “LastDay” and the accompanying photographin the June issue of the Bulletin(“Collection”). Part of the poem reads:“I sit on the steps / of the dorm andsmoke a cigarette,” and the photodepicts a girl, puffing away, surroundedby smoke.This implicit—if unintentional—endorsement of smoking disturbs me.We are all aware that cigarette smokingkills. Would you publish a similarpoem about students playing Russianroulette in the dorms as if it were themost everyday activity in the world,next to a photograph of a studentholding a gun to her head?If such unhealthy and often fatalbehavior were not so socially acceptable,it would not find its way intosuch forums as the Bulletin. Part of theproblem with getting people to recognizeand accept the dangers of smokingis that it is so deeply entrenched inour society—as American as apple pie.Although a single poem may not convincean adult to take up smoking,thousands of such words and imageslegitimize smoking, adding to itsacceptability and downplaying thedanger involved. As the publication ofa socially conscious institution, theBulletin should refrain from supportingthe harmful status quo.AMITA SUDHIR ’98Falls Church, Va.SMOKING DECEPTIONReading the June 2000 issue of the Bulletin,I was shocked and then angeredto see in the “Collection” section aphotograph of a young woman smokingand to read the adjacent poemwith the line, “I sit on the steps / of thedorm and smoke a cigarette.” The photographappears to be a portrait of thepoet, accompanying her republishedliterary contribution. In this context,your readers might reasonably expectthat the person and her behavior aremeant to be admired.Portraying smoking as admired (oreven acceptable) deceives young peoplewho have not seen the ugly truthabout nicotine addiction; tobaccoinducedcarcinogenesis; and the consequent,very painful, fatal diseases.Of all places, I expected Swarthmorewould not tolerate the deception.MARK DEWITTE D.V.M. ’73Downingtown, Pa.Editor’s Note: College policy prohibitssmoking in all public spaces. Accordingto Linda Echols, director of the WorthHealth Center, although the College’sgoal is a smoke-free campus,“when wetalk about quality of life for the community,we still debate smoking—a person’sright to do so and others’ right notto have to breathe smoky air.” Thehealth center offers smoking cessationprograms and provides access to otherPlease turn to page 71L E T T E R SS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 03

4C S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NO L L E C T I O N2000C o m m e n c e m e n t 2 0 0 0Amid mortarboards decoratedwith the requisite trappings ofCommencement—happy faces,origami, pinwheels—hundreds of familiesand friends gathered to cheer theseniors receiving their degrees onMemorial Day.In addition to the Oak Leaf, Ivy, andMcCabe Engineering awards, the presentationof a new special award wasadded to the ceremony. Established byEugene Lang ’38, the Lang Award isgiven by the faculty to a graduatingsenior in recognition of outstandingacademic accomplishment. JacobKrich, a Rhodes Scholar, is its firstrecipient. Of the 377 graduates, 359collected the bachelor of arts degreeand 21 the bachelor of science. Highesthonors were awarded to 10, highhonors to 52, and honors to 37.“We decided long ago never to walkin anyone’s shadow,” said senior-classspeaker Rhiana Swartz, a political sciencemajor from Amherst, Mass., paraphrasinga line from a song. “Swarthmoregave us all an inner drivestronger than we had ever experiencedbefore. It is this that will staywith us.”RHODES SCHOLAR JACOB KRICH ‘00,WINNER OF THE FIRST LANG AWARDFOR OUTSTANDING SCHOLARSHIP,CHATS WITH EUGENE LANG ‘38.Photographs by Steven Goldblatt '67W I S D O M A N D C O M M I T M E N TThe first to receive one of three honorarydegrees was Ian Barbour ’44,a theologian and physicist internationallyrecognized for his pioneeringefforts to forge a dialogue between scienceand religion. An emeritus professorof religion at Carleton College, Barbourwon the Templeton Prize forProgress in Religion in 1999. In hismany books, he has also exploredsocial, environmental, andethical issues related to technology,energy policy, and genetic engineering.ELIZABETH “BETITA” MARTINEZ ‘46,HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTBefore beginning his preparedremarks, Barbour reminisced aboutcurfews and physics labs in TrotterHall. He also recalled witnessing as afreshman John Nason’s inaugurationas president and expressed gratitudethat, at age 95, President Nason was inattendance for the day’s events.But Barbour’s real message wasabout the future, not the past. He suggestedto the graduates three ways inwhich new discoveries would challengetheir thinking: “Molecular biologywill vastly increase our understandingof biological phenomena, and wewill be tempted to think that it will beable to explain everything.… Astronomywill challenge our ideas of God.…

C o m m e n c e m e n t 2 0 0 0Technology and the application of sciencewill raise new ethical issues.…“As you leave Swarthmore, you willbe under various kinds of pressure tospecialize. Some of you will be in competitivejobs in which your success isjudged by narrow criteria. Others willbe in graduate programs requiringintensive specialization, and it will betempting to think that your disciplinehas all the answers. So let me encourageyou to keep an interdisciplinaryperspective as you encounter the discoveriesof the new millennium. I hopeyou will reflect on the ethical issuesarising from your work and seek waysto express your concern on your joband through public interest groups,community organizations, and politicalprocesses. My wish for you is wisdomand commitment in working for justiceand sustainability on our amazing andbeautiful planet.”A D A R E T O D A N C EExtemporaneous remarks from a selfdescribed“48-year-old radical”clearly resonated with graduates. In arich baritone, acclaimed dancer andFLANKED BY JAMES HORMEL ‘55 AND“My wishPRESIDENT ALFRED H. BLOOM,CHOREOGRAPHER BILL T. JONESfor you isRECEIVES HIS HONORARY DEGREEMARI MCCRANN ‘00wisdom andcommitmentin workingfor justice andsustainability.”—Elizabeth “Betita”Martinez '46choreographer Bill T. Jones began bysinging a verse from a spiritual, thencommented:“Lovely, isn’t it? It’s lovely, but it’salmost too easy ... good old-fashionedreligion. You know, they say AfricanAmericans can sing the phone book,and it sounds profound. It can be acheat, and excuse me in front of suchan august company of thinkers tocome out with such a performativestrategy. I am a performer. And in myworld, sometimes [being] a performermeans you are lacking intellect. I am aperformer. And words like performerequate with narcissism, self-indulgence,alienation, self-involvement—allqualities that have been exorcisedfrom the curriculum of your school, Iunderstand.”“So I say to you, what can I chargeyou with?” Jones asked, then presentedhis own philosophy of life: “I’mS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 05

6C S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NO L L E C T I O N2000C o m m e n c e m e n t 2 0 0 0gonna dance in one door; I’m dancingout the other. I want my dance to bebigger and more generous, and youknow what? When people say to me atcocktail parties, ‘Oh, I have two leftfeet; I’m too fat; I’m too old,’ I’m saddenedby that. Dancing is like yourvoice…. It’s a gift to you. Everyone cando it. I danced with a woman with noarms and legs three years ago in Vienna.What was that dance? It was sexy.It was real. And if dancing is a symbolDESIREE PETERKIN ‘00 (CENTER)of what it means to be alive, I dare youto dance bravely. I dare you to befierce, and I dare you to be outrageousand generous.”To conclude, Jones sang again, thistime part of the chorus from “Brass inPocket.” And then his long framebecame a whirlwind of twirling academicrobes as he danced across thestage and bowed.G I V I N G T H A N K SElizabeth “Betita” Martínez ’46, a lifelongadvocate for civil and politicalrights, received an honorary doctor oflaws degree. In her remarks, she notedhow proud she is to be the College’sHONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTIAN BARBOUR ‘44 (BELOW)CHRISTINA SORNITO ‘00 AND SAMANTHA LAPETER ‘00 GRADUATED IN STYLEfirst Latina graduate. “My father, whoimmigrated to the United States fromMexico, would be so proud. But I ameven prouder of the fact that therewere seven more Swarthmore graduatesnamed Martínez in the 1990s! Solet me give a special salute to the Latinaand Latino graduates here todayand all their familias.”Recalling her childhood in Washington,D.C., Martínez said she learnedabout racism and the common experienceof blacks and Latinos. She alsosaid that World War II, which startedwhen she was 14 years old, taught hersimilar lessons about anti-Semitismand the dehumanization of Asian peoplesduring the internment of JapaneseAmericans in U.S. concentrationcamps.“The great social movements of the1960s, which I quickly joined, confirmedthat people did not have to liedown and let such injustice roll on forever.Women like Ella Baker and FannieLou Hamer, men like Corky Gonzalesand César Chávez—those are all peoplewho taught that truth and whom Imust thank.“Those were years of great courage,personal sacrifice, and real achievement.But we should also recognizethat being part of the global humanstruggle for social justice can bring asense of personal fulfillment and happiness.I deeply hope all of you graduatesmay someday know that kind ofhappiness.”—Alisa Giardinelli

H u m a nc o m m o n a l i t yF R O M P R E S I D E N T A L F R E D H . B L O O M ’ S C O M M E N C E M E N T A D D R E S SBefore you set out further into the world, let me drawyour attention to a habit of mind that Swarthmorehas reinforced in you and that will be critical to theleadership you provide—namely, your readiness to seebeyond differences to the astounding commonality in conceptual,emotional, and ethical life, which similar geneticcodes, combined with fundamentally similar experience,have conferred on all human beings—a commonality thathas become all the more encompassing as global communicationand contact have spread common aspirations, andcommon modes of thinking and valuing, more broadlythan ever before.You have come to recognize that, although the particularsof what is learned will be different, except in caseof severe impairment, all human beings share the abilityto learn, to stretch conceptual categories, to discriminateamong them, to build new ones, to think with words andbeyond words, and to combine the words of their own languageto capture ideas expressed in another.You have come to recognize that, although emotionsmay be expressed or suppressed differently,all human beings share thecapacity for being amused or bemusedby irony, for being inspired by beautyor heroism, for appreciating a pat onthe back or a wink of an eye, forengaging in conscious deception orwell-intentioned white lies, for feelingrespect in the presence of anadmired teacher, or stage fright inthe face of a large audience, or amixture of elation and anxiety at aceremony marking the passage to anew stage of life.And you have come to recognizeas well that, although virtues andresponsibilities will be defined differently,all human beings share a senseof moral obligation to social groupsor to religious or ethical principlesbeyond themselves; judge moral conducton the basis of both intentions and actions; valuequalities akin to integrity, fairness, and trust; expectappropriate reciprocity; appreciate generosity; and resenttreatment they deem oppressive or unjust.You have built that recognition of fundamental humancommonality through exploring the universalities ofhuman physiology, psychology, language, and behavior;through discovering the similar ends for which humaninstitutions, across time and cultures, have beendesigned; through becoming aware of the contributionsthat diverse cultures have made to universal advances inmathematics, technology, and science.I believe there is nostronger argument fordiversity on collegeand university campusesthan its crucial rolein developing aninternalized recognitionof fundamentalhuman commonality.You have built that recognition of commonalitythrough being moved intellectually, aesthetically, emotionally,andethically by thevoices of othercultures, times,and circumstances,as expressedin theirart, literature,music, and philosophy;and by realizing how often those voices speak toideas, sentiments, and values that are meaningful to you.You have built that recognition by witnessing in yourown engagement with other languages and cultures howmany of the subtleties of other worlds can ultimately beunderstood, precisely because we share the underlyingfoundations of our conceptual, emotional, and ethicallives.And I would suggest that no experience has beenmore critical to developing that habit of recognizing commonalitythan living and working together in a diversecommunity, dedicated to shared goals.It is often harder and more transformingto recognize similarity acrossdivides closer to home—over race,class, sexual orientation, ability, disability,accents, interests, beliefs, orlifestyle—than across more distantand thus less threatening divides.And the diversity of this communityhas allowed you, in one instance afteranother, to discover how much youshare beyond those socially constructed,initial perceptions of difference.In a world of unprecedentedwealth and opportunity, your readinessto recognize human commonalitymakes clear that those who have notbenefited from that wealth and opportunityare not fundamentally differentfrom yourselves or fundamentally lessdeserving.And that recognition prompts you to use your voiceand talents to awaken collective responsibility to createconditions that allow everyone the real chance to achievea better life.In a world that tends to dismiss humane approachesto conflict resolution as weak or naïve because it perceivesthose on other sides of international culturaldivides as responsive only to threat and punishment, yourrecognition of human commonality makes clear thatresponsiveness to extensions of generosity and trust—andcapacity to be moved by shared vision—are as distributedin other societies as in our own; and that the resultsPlease turn to next pageS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 07

C O L L E C T I O NS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NH U M A N C O M M O N A L I T Y ( C O N T I N U E D )achieved through affirmative, and particularly mutual,initiatives are more likely to be lastingly embraced thanthose that are unilaterally imposed.And that recognition prompts you to use your voiceand talents to insist that approaches based on the constructiveattributes we share have been adequatelytried.In a world in which single-dimensional human differencesare so readily inflated into stereotypes thatdistance and discount the other as a whole, your recognitionof fundamental human commonality compels you,in your personal interactions with individuals andgroups, to refuse to define others by their differenceand rather to reach for the common ground you knowyou share.And that recognition prompts you to use your voiceand talents to lead our societies both to respect differenceand to understand how easily exaggerating differencecan destroy community and undermine justice andpeace.I believe there is no stronger argument for diversityon college and university campuses than its crucial rolein developing that internalized recognition of fundamentalhuman commonality.You, the Class of 2000, have been the most diverseclass in the history of this College and have drawn onthat essential context to respect what each other bringsand to see beyond it to what you share.In so doing, you have each developed a habit ofmind that transforms you into an agent of connectionamong the individuals and across the groups and societiesof our world. And you have collectively defined aclearer standard of distinctive achievement for all futureSwarthmore classes to meet.Thank you, Class of 2000, for that central contributionto this institution’s remarkable educational legacyand for the multiple additional ways in which you havehelped Swarthmore to become an even finer institutionas it enters the 21st century.P O S T D O C P R O G R A M S F U N D E DFor the past three years, Swarthmore has hosted postdoctoralteaching fellows in several fields in the humanities,such as religion, classics, and philosophy. Now a $1.5million matching grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundationwill help endow the program.“By creating an endowment for the program, we will beable to continue to attract a more diverse faculty,” saysProvost Jennie Keith. “We will also be able to enrich thecurriculum, especially in small departments in which certainfields may get little or no attention.”The Mellon Foundation also continued its support of afellowship program intended to increase the number ofminority students in Ph.D. programs in the arts and sciences.With funding assured through 2005, an additional20 Mellon Minority Undergraduate Fellows will be able toparticipate in the program.JIM GRAHAMF O R M E R D E A N G E T ST O P P R I N C E T O NP O S I T I O NJanet Smith Dickerson,who served as dean of theCollege from 1976 to 1991,has been named vice presidentfor campus life atPrinceton. She has served asvice president for studentFORMER DEAN JANET SMITH affairs at Duke UniversityDICKERSON’S SMILE STILL GRACES since 1991. Dickerson will bethe first African-AmericanPARRISH PARLORS, THANKS TO THISwoman to reach the level ofPORTRAIT PAINTED IN 1991, THEvice president at Princeton.YEAR SHE LEFT <strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>. “One of the things thatappealed to me about thisposition was my recognition that Princeton was probablysomewhere between Swarthmore and Duke in its size, spirit,culture, and intellectual nature,” Dickerson said from hernew office. “Swarthmore was a very seminal experience forme.”BOARD ASKS FOR ATHLETIC REVIEWAcommittee appointed by the Board of Managers has metfour times since February to review the intercollegiateathletics program at Swarthmore and address concernsraised in recent years by the Admissions Office as well ascoaches and student athletes.The Athletics Review Committee is charged with assessing“the health of the intercollegiate athletics program”—inparticular, the quality of experience it offers to student athletes—andof “the relationship between that program andthe mission of the College.” Members of the committee willdecide which areas need improvement and make recommendationsin December.“The overall goal is for us to have a strong intercollegiatesports program,” explains Provost Jennie Keith, chair of thecommittee. “There have been tremendous changes in collegeathletics in recent years, and we are trying to understand theimpact these changes have had on our program.”Committee members include the president, the dean, thedean of admissions, five members of the faculty, five membersof the Board of Managers, and four students. “We’rehoping that the work of the committee will strengthen thequality of the athletics program and the experience it providesstudent athletes as well as the quality of the College’sadmissions,” Keith says. “It’s an incredibly broad charge.”N E W J O U R N A LTeaching emerging diseases and using computer technologyin science education were some of the subjects tackledin the first issue of Microbiology Education, a new quarterlyjournal put out by the American Society for Microbiology,published in May. Amy Cheng Vollmer, associate professor ofbiology, spent several years helping to develop the journaland now chairs its editorial committee.8

F A N T A S Y F O O T B A L L G U R UTED CHAN ‘02Pro football is back in season,which means ultrabusy Sundayafternoons for Ted Chan ’02.Besides watching a couple NationalFootball League (NFL) games at a timeon television, Chan can be found monitoringanother half-dozen matches viathe Internet. Who’s piling up theyardage and touchdowns? Who’s beeninjured? Who’s earning a one-way ticketto the bench?It’s more than football fanaticismthat drives Chan to keep track of theNFL the way day traders watch themarket. Despite his mere 20 years ofage, Chan is a nationally known profootballsage, part of a team thatwrites The Guru Report for the growinglegions of fantasy football enthusiastsacross America. The report has itsown Web site (www.gurureport.com)and is also seen by thousands onESPN.com, one of the most popularsports sites on the Internet.“Most readers don’t know my age,”says Chan, a Boston-area native andNew England Patriots fan who becamea “guru” at 15. “The editor of The GuruReport didn’t know for the first two orthree years I wrote for him.” By thetime he found out, Chan was a seniorwriter with a big following.For the uninitiated, fantasy sportsare a wildly popular spin-off of realsports that allows fans to form andrun their own teams and competeagainst one another. “Owners” accumulatepoints based on the real-lifeperformances of players they acquirein their leagues’ annual draft or auction.Although fantasy basketball,baseball, and football leagues havebeen around for decades, the pastimehas grown exponentially since theadvent of the Internet, with a satelliteindustry of league management toolsand inside information sources boomingalongside it.Game-day action is only one part ofthe seven-day-a-week, year-round jobof staying on top of pro football. Midweek,Chan, an Honors history majorand member of the varsity wrestlingteam, is busy keeping track of rostermoves and analyzing upcominggames. How will the Colts’ EdgerrinJames perform on natural grass Sunday?How effective does the San Diegodefense figure to be against theBrowns?Chan, known to many of his fellowSwarthmore students for his outspokensports columns in The Phoenix,was first introduced to fantasy sportsin seventh grade when two mathteachers at his school started a basketballleague to teach students aboutstatistics. “My best friend, who’s nowat Harvard, took part in the leaguewith me, and we both got completelyhooked,” Chan says. “Within twoyears, I was doing football, baseball,hockey, and basketball on the Internetand in local leagues.”By the time he was 15, Chan wasspecializing in his favorite, fantasyfootball. Also interested in journalism,he wrote a sample article for the fledglingGuru Report and submitted it tofounder and publisher John Hansen,who quickly brought him on board.This season, he is fielding questionsfor the call-in segment of a Sundaypregame radio show broadcast in St.Louis.“People say I have a knack for seeingtalent well in advance,” Chan says.“Watching a lot of college footballhelps me spot talent. I also read footballinsider reports and absorb anyother information I can get.”Chan has developed his own pettheories about how best to build a fantasyfootball team. His advice in onerecent Guru Report column: If youcan’t get a big-name quarterback inthe first or second round of your draft,wait until much later—you can probablyget someone good on the cheap.Not so with wide receivers and runningbacks; the field of top performersis not as deep. Chan advises gettingpass catchers and ball carriers earlyor risk being stuck with comparativedeadbeats at those key positions.His approach is being put to thetest this fall in one of the biggest andmost high-profile challenges of his fantasysports career. Chan is runningThe Guru Report’s franchise in a newsuperleague that is pitting the topinsider reports against one another.Going head-to-head against such rivalsas Pro Football Weekly, The SportingNews, and Rotonews can be a littledaunting, he admits. “I don’t want tolet The Guru Report down,” Chan says.“A lot of money and visibility are atstake. You also realize that whenyou’re dealing with such top-notchcompetition, much of it will comedown to luck.”Despite his apparent career track,Chan does not plan to pursue sportswritingafter Swarthmore; the fieldoffers too little security, he says. He ismore likely to become a technologyentrepreneur, he says, and, towardthat end, has already started a Webdesign and marketing company. Notthat he wouldn’t love to find a professionalniche in sports. His dream job:owner or general manager of a realmajor league sports team.—Tom KrattenmakerS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 09

C O L L E C T I O NS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NS a v i n g t h e b i r d sWWhen a “Green Team” was formed to advise on theenvironmental aspects of the College’s new sciencecenter—an 80,000-square-foot complex projected tobegin construction next June—its members did not havebirds in mind. The group was to research and report onsuch matters as recycling building materials; reducing stormwater runoff outside and energy usage inside; and thecost-effectiveness of wind turbines, ground-sourceheat pumps, and solar hot-water heaters.Now, minimizing bird deaths hasbeen added to the list.It seems that the center’sScience Commons,designed, in part, by MargaretHelfand ’69, an architect of Kohlberg Hall,will involve two stories of plate glass looking out onCrum Woods. There, students and faculty members will beable to relax and observe, firsthand, the natural sciences atwork.But plate glass can be hazardous to the wildlife it makesso beautifully accessible. This fact was evident in a reportforwarded to the Green Team last spring by Guido Grasso-Knight and Michael Waddington, then senior biology majorswho had conducted a study of bird deaths on campus for anornithology class taught by Professor of Biology TimothyWilliams ’64.Although they found only one dead bird during theirresearch, reports from around campus and smudges on windowsled them to estimate that about 100 birds die eachyear from hitting the windows of College buildings. Anothersix birds were found dead and four seriously injured underwindows last spring that were not recorded in the study,Williams adds. Downed birds are quickly eaten by other animals,the students reported, so evidence of collisions is difficultto track. Although they admit their methods of recordingevidence were “less than optimal,” their findings leaveno doubt that the danger zones for birds are Kohlberg Halland the Cornell Science and Engineering Library, both ofwhich sport large plate-glass windows. Kohlberg aloneaccounted for 75 of the 100 estimated deaths.Soon after reviewing this study, the Green Team invitedDr. Daniel Klem Jr., a professor of biology at MuhlenburgCollege, to lecture on bird collisions, a topic on which hehas written dozens of papers. Klem estimates that “windowmortality” claims as many as 975 million birds in NorthAmerica—10 percent of the bird population—each year. Theevolution of flight among birds, he explains, has not yetadapted to man-made phenomena like tall buildings, artificiallight, and large expanses of glass.Two years ago, five hummingbirds were found dead inKohlberg Hall’s Cosby Courtyard, a garden surrounded onthree sides by plate-glass windows. Associate Professor ofBiology Sara Hiebert ’79, who studies hummingbirds, saysthat those five represented a substantial part of the hummingbirdpopulation on campus.“The Scott Arboretum staff had planted certain bushes inthe courtyard to attract birds and butterflies,” says ProfessorWilliams. “They didn’t realize that they were actuallyattracting the birds into a death trap. After they realized theproblem in 1999, they removed the nectar-producing bushes,and we only had one or two hummingbirds killed thatyear.”Now the Green Team has begun its own research into theproblem. Their primary concern is how to prevent the College’snewest building from becoming another “deathtrap.” Carr Everbach, associate professor of engineeringand chair of the Green Team, explains that “either birdsare looking through the glass to the other side and tryingto fly through, or they see a reflection of trees andsky and fly into it.”“Hawk silhouettes,” the black birdshapeddeterrents that adhere to windows,are useless at warning birdsoff, Everbach adds. Unfortunately,he concludes, bird collisions are“a problem without a perfectsolution. Klem has made a pleafor nonreflective matte-finishedglass, but this is very expensive and would beimpractical for this project,” he says. “Any window largerthan 4 square inches looks like an opening to most birds. Ifbirds think they’re seeing a path, however narrow, they willtry to fly through. The only real solution is to build buildingswith no windows, but that won’t happen.”“In fact, birds rarely collide with any window smallerthan 1 foot across, although it does happen,” Williams adds.“The windows of other buildings such as Parrish and Martinrarely have bird collisions. It is only since the constructionof Cornell that there have been reports of collisions at theCollege. Kohlberg was the first building on campus to bringthe bird mortality to crisis levels and the first to use massiveopen-glass areas.”Among the bird-friendly measures being considered,Everbach says, is the proper placement of bird feeders.“One of Klem’s observations is that if bird feeders areplaced two to three feet from the glass, birds won’t get upenough speed, flying from the feeder, to be seriouslyinjured,” Everbach says. Feeders placed 10 or more feetfrom the glass, on the other hand, are deadly. “So item 1 isto put feeders up against the glass of the new building—which will also be nice for people who want to watch thebirds.”Another idea the Green Team is considering is the placementof finely woven, transparent mesh about a foot fromwindow exteriors. “A bird would hit a trampoline, essentially,and bounce off,” Everbach explains. “The netting wouldbe mostly invisible from inside the building. It would helpduring the bird migration season but would have to beremoved during the fall and winter when leaves and snowwould stick to it. Our idea is to have motorized rolls of thisflexible mesh that roll out under the eaves, then retract duringwinter.” (More information on the Green Team’sresearch—and a detailed look at current plans for the entirescience building—is available at http://sciencecenter.-swarthmore.edu.)—Cathleen McCarthyACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES/VIREO10

GEORGE WIDMANCOACH KAREN BORBEE TEACHES LACROSSE DAYCAMPERS IN JUNE.D a yc a m p i n gWhile parts of the College campusare deserted during the summer,the athletic fields are bustling. Lookclosely, however, and you notice thatthe athletes are often smaller thanusual.Summer is sports camp time atSwarthmore, when coaches find themselvesteaching children the tricks ofthe game. This summer, four Swarthmorecoaches ran sports camps.Women’s basketball coach AdrienneShibles and men’s lacrosse coach PatGress each ran 5-day day camps, for 8-to 14-year-olds. Wrestling coach RonTirpak taught wrestling to high schoolersin the evenings for two weeks inJune. And Karen Borbee, coach of thewomen’s field hockey and lacrosseteams, ran two 5-day camps for 10- to15-year-olds: one for field hockey andone for lacrosse.Borbee started her sports daycamps at the College seven years ago,aiming at middle school students.“Now I work with students as young as8—if they’re really interested—and asold as high school freshmen,” shesays. “My philosophy is to teach thebeginner and intermediate. These areintroduction camps. We provide theequipment and let children try out thesport and see if they like it.“Teaching girls this young is fun ina different way,” Borbee says. “You’reintroducing a sport to a child. But thefunny thing is, as different as thesekids are in age and experience fromcollege students, they’re also very similar.I use the same philosophy that Iuse on my college students. Basically, Iwant it to be fun. I want them to learnthe skills and basic strategies, butmostly I want them to enjoy playing asport. If it’s not fun, they won’t continue—andwe want them to continue.”Borbee says Swarthmore is an ideallocation for sports camps. “We havebeautiful fields, and we’re centrallylocated to so many schools wherelacrosse and field hockey are popular,”she says. “With kids starting sportsyounger and younger, associationsand youth clubs are springing up allover the area. Working parents arelooking for places to send their kids inthe summer and trying to be morespecific about their interests.”She can see the effects of sportscamps on her college student athletes.“You can tell the kids who’ve gone tocamp. They have good basic skillsbecause that’s what camps emphasize.Those who just jump into scrimmagingand game situations are often missingthat.”—Cathleen McCarthyN E W L Y T E N U R E DThe following faculty members haverecently been promoted to the rank ofassociate professor with tenure: SaraHiebert, biology; Haili Kong, Chinese;Lisa Meeden, computer science; PhilipJefferson, economics; Nora Johnson,English literature; Patricia White, Englishliterature; Timothy Burke, history;Michael Brown, physics; CynthiaHalpern, political science; Frank Durgin,psychology; Sarah Willie, sociology;and Maria Luisa Guardiola, Spanish.t h i s y e a r ’ sf a l lI think about breathall the time. the breathof sky on our hands,breath of wind turningthis red autumninto another half-moonmemory.this city eases meinto smaller days,sun falling in-betweenthe hours and I watchthe breath of air alongmy back.this city cringesletters back at nightand writes an encryptedmessage: the mysteryof our ancient hearts.I touch stones,hands skimming wet,broken rock and feelthe loss of anothercity, each town returnedto oblivion.maybe it’s how deathstorms. or the threatof (another) warbut I’m tired of writingthese lettersthat crumble at the touch.I’ve heard the echoof endless grief and whatit means to be eternal.I can’t call thisthe eternal city yet.I’m too young and storiesthat rise out of milkshopsand cemeteries only make me tired.this fall cools summer’sslum as I watch a river gleamwith the memory of mythic babies.eternal. this place.it shifts words back into a languageI thought I knew but autumnhas turned this fall into ruins,the breath of wandering.—Lena Sze ’01Lena Sze is a classics major from NewYork City. She was studying in Rome lastfall when she wrote this poem. It wasfirst published in the winter 1999 issueof Small Craft Warnings, a student literarymagazine.S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 011

From the Bard to BelovedI N E N G L I S H C L A S S E S , S H A K E S P E A R EA N D O T H E R I C O N S A R E S H A R I N G T H ES P O T L I G H T W I T H N E W E R W R I T E R S .By Tom KrattenmakerS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NILLUSTRATIONS BY JANE OʼCONOR12

There it is in black and white in Swarthmore’s coursecatalog—evidence of what some claim is a politicallydriven preoccupation with present-day issues like raceand gender in America’s English literature departments.As the catalog puts it, “A special effort is made to keep inview, at all times, the application of the works studied to thelife and problems of the present day.” One problem: Thepassage comes from the College’s 1930 catalog.Perennial charges that English literature curricula aremired in political correctness and disrespect for theWestern canon were back in the news in recent months,prompted by a well-publicized report from the right-leaningNational Association of Scholars (NAS).“Want to major in English at one of America’s ‘top’ universities?”asked the headline of the news release issued bythe NAS last spring. “Don’t expect to learn much about greatliterature or authors.”But as the English faculty members at Swarthmore arequick to point out, the NAS report and similar broadsidesexaggerate the extent to which Shakespeare and other iconsof the Western canon have yielded turf to newer writers.Although today’s English literature students read a somewhatdifferent mix of writers than previous generations—and surely with different critical approaches—two constantsremain: high standards for analysis and writing and theinevitability of curricular change.“Looking over the old catalogs, it’s clear that the wholeenterprise has always been in flux,” said Charles James, theSara Lawrence Lightfoot Professor of English Literature andchair of the department, as he paged through the 1930 edition,“and that is as it should be.“There is also stability. No matter what year’s catalog youlook at, you’re going to find lots of Shakespeare. Our criticssay they are concerned about tradition. But in our view,change, alongside an appropriate amount of stability, is animportant part of that tradition.”The report by the Princeton, N.J.–based NAS, which generatedcoverage by the Chronicle of Higher Education andscattered newspapers around the country, went on to detaila supposed dumbing-down and politicization of the Englishcurricula at 25 leading liberal arts colleges. Swarthmore waslisted as a chief offender.Among the principal charges: That courses dealing withrace, gender, and sex—almost unheard of 40 years ago—areproliferating, revealing “an infusion of terminology more ideologicalthan literary”; that traditional greats such asShakespeare, Henry Fielding, and Jonathan Swift are beingcrowded out by the likes of Toni Morrison and Zora NealeHurston; and that broad survey courses are waning, as theyare replaced by tightly focused and highly theoretical coursesthat leave English majors without an adequate literaryfoundation.The report concludes: “Many of the graduates of theseprograms, though no doubt priding themselves on havingreceived a first-class literary education, must possess onlythe most rudimentary knowledge of English literature’slonger history, or of its greatest writers and works. Whatthey’ve probably gotten instead is ... an exposure to dubious‘theoretical insights’ and a familiarity with trendy authors ofapproved identity and outlook, likely to soon be forgotten.Anyone concerned about preserving our rich and creativeliterary culture has good reason to be alarmed.”The trend to which the NAS objects is typified in manyways by English 054, “Faulkner, Morrison, and the Representationof Race,” a course taught by the Alexander GriswoldCummins Professor of English Literature Philip Weinstein,who joined the faculty in 1971. One of the department’sadvanced offerings, Weinstein’s course juxtaposestwo great American writers of different eras, sexes, andraces and assesses their achievement with an eye towardthe role of race as well as more traditional criteria.“The central argument of the course is that race is primary,but that lots of other questions are as well,” Weinsteinsays. “We need to acknowledge race and what it brings tothese writers’ unique voices but also see that whiteness andblackness are not the only things affecting their work.”Weinstein, who is a former department chair, says hedesigned the course as a way to stake out a middle groundbetween two extreme approaches to English literature. Inone such approach, which prevailed until the 1960s, race isdeemed irrelevant. Literary masterpieces are thought topossess a universal greatness because they capture thetimeless essence of the human condition. The fact that mostof the favored writers are white males from long ago doesn’tmatter from this viewpoint. Until things began to change inthe 1960s, “hardly anyone,” Weinstein said, “ever talkedabout race as a shaping factor.”According to the other extreme position he sees, race isthe only issue. From this angle, the recognition accorded thesupposed masterpieces is merely the product of the privi-A U T H O R , A U T H O R !The 1999-2000 Swarthmorecourse catalog listed morethan 100 courses in theDepartment of EnglishLiterature. All of the authorsmentioned in course descriptionsare noted on thesepages. (Thanks to intern—and English major—AndreaJuncos ’01 for compiling thislist.) Read full descriptions ofthese courses at www.swarth-more.edu/Home/Academic/-catalog/dept/english.html.Chinua Achebe Theodor Adorno Aijaz Ahmad Ama Ata Aidoo Chantal Akerman Sherman Alexie Dorothy AllisonSamir Amin Hannah Arendt Nancy Armstrong Matthew Arnold Isaac Asimov Margaret Atwood W.H. AudenJane Austen Mariama Ba Francis Bacon Joanna Baillie Mikhail Bakhtin James Baldwin Charles-Pierre BaudelaireSamuel Beckett Aphra Behn René Benjamin John Berger Marshall Berman William Blake Eavan BolandJorge Luis Borges David Bradley Bertold Brecht Split Britches The Brontës Elizabeth Barrett BrowningRobert Browning Emil Brunner Edmund Burke Fanny Burney Judith Butler Octavia Butler Lord ByronItalo Calvino Maria Campbell Elias Canetti Thomas Carlyle Ciaran Carson Angela Carter Elizabeth CaryWilla Cather Aime Cesaire Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Raymond Chandler Geoffrey Chaucer Charles ChesnuttLydia Maria Child Noam Chomsky Kate Chopin Caryl Churchill Sandra Cisnceros Arthur C. Clarke Jean CocteauJudith Ortiz Cofer Samuel Taylor Coleridge Wilkie Collins Joseph Conrad Stephen Crane e.e. cummingsTsitsi Dangarembga Dante Charles Darwin Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton Michel de Certeau Daniel DefoeThomas Dekker Martin Delany Teresa de Lauretis Nuala Ni Dhomnaill Charles Dickens Emily DickinsonS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 013

leged positions of the white men whowrote them and the other white menwho taught them in colleges and universities.From this viewpoint, no workis inherently better than any other;everything is relative and the productof the writer’s orientation. By thisapproach, “we can no longer speak ofliterary masterpieces because all we’retalking about is literary politics,”Weinstein says.“My aim with the Faulkner–Morrisoncourse is to give race and gender the full play they deservewhile keeping Faulkner from disappearing into his whitemaleness and Morrison from fading into her black femaleness.”Weinstein’s is hardly the only course at Swarthmoreexamining literature with an eye toward the issues of thelate 20th and early 21st centuries. For example, AssistantProfessor Carolyn Lesjak teaches “Modern Bodies in theMaking: The 19th-Century Novel,” which examines works byAusten, Dickens, Eliot, and others to explore the formationof class, gender, and racial identities. Associate ProfessorNora Johnson teaches a course called “RenaissanceSexualities,” which mines Renaissance-era texts to understandthe sexuality of that time. How were concepts ofchastity, friendship, marriage, and homosexuality differentin the Renaissance? “This is the place where we study thecanon and at the same time use a tool that has the excitementof postmodern inquiry,” Johnson explains.Is this legitimate grist for the Swarthmore classroom?Absolutely, says Associate Provost and Professor CraigWilliamson, a scholar of medieval British literature and formerdepartment chair. “Is love in Elizabethan England thesame as in today’s America?” he asks. “Is the idea of genderthe same? If not, how is it different? Is the idea of sin thesame? The answer to all these is ‘no, not exactly,’ and it’simportant to understand the differences. Without courseslike these, students are tempted to talk about love inShakespeare as if Shakespeare were the person livingaround the corner from them. Many things change in culture,and that’s one of the dialogues we’re trying to create.What is consistent? What is different? If you’re really goingto understand Shakespeare, you have to know.”Johnson disagrees with the NAS contention that questionssuch as these are better left to historians. “No, thisAlthough today’s students read atwo constants remain: high standards forand the inevitabilityW I L L I A M F A U L K N E RHilda Doolittle John Donne Fyodor Dostoevsky Frederick Douglass Rita Dove Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Theodore Dreiser W.E.B. Du BoisS W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NMarguerite Duras George Eliot Queen Elizabeth I Ralph Ellison Buchi Emecheta Olaudah Equiano Louise Erdrich Franz Fanon William FaulknerHenry Fielding Gustave Flaubert John Ford Maria Irene Fornes Edward Morgan Forster Michel Foucault Mary Wilkins Freeman Sigmund FreudErnest Gaines Gabriel Garcia Marquez John Gardner Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell William Gibson George Gissing Susan Glaspell Guillermo Gomez-PenaSue Grafton Radclyffe Hall Dashiell Hammett Peter Handke Donna Haraway Thomas Hardy David Harvey Nathaniel Hawthorne Eliza HaywoodSeamus Heaney Felicia Hemans Ernest Hemingway George Herbert Mary Herbert Robert Herrick Etty Hillesum Alfred Hitchcock bell hooksW.D. Howells Langston Hughes Ted Hughes Zora Neale Hurston Aldous Huxley David Henry Hwang Luce Irigaray Henrik Isben Henry JamesFredric Jameson Charles Johnson James Weldon Johnson Ben Jonson James Joyce Franz Kafka John Keats Margery Kempe Adrienne KennedyJack Kerouac Maxine Hong Kingston Jamaica Kincaid Rudyard Kipling Aemilia Lanier Nella Larsen D.H. Lawrence Ursula Le Guin L.E.L.Claude Levi-Strauss Matthew Lewis Kenneth Lincoln Audre Lorde Gyorgy Lukacs Thomas Mann Christopher Marlowe Paule Marshall Andrew MarvellKarl Marx Medbh McGuckian D’Arcy McNickle Herman Melville James Merrill Thomas Merton Thomas Middleton Tiffany Midge John Stuart Mill14

somewhat different mix of writers,analysis and writingof curricular change.T O N I M O R R I S O Nkind of inquiry shouldn’t be the only thing we do inEnglish literature,” she says. “We still need to study thebeautiful words. But knowledge has changed so muchover the last century that we need to have this kind ofconversation.”Although critics of curricular change contend thattoday’s scholars have no business imposing their concernson the great old literature, Weinstein and otherscontend that this approach has always been the practiceand, in truth, is the only possible way to read literature.“There’s nothing else we can do,” Weinstein says.“We can’t take off our year-2000 glasses. They’re notexchangeable. What you can do is be aware that you’rewearing those lenses and seek to accent them as much aspossible with what you can learn about the lenses of a differenttime. But you can never put yourself back in time insome naive way and see Hamlet as a man or woman in the1600s would.”Speaking of Hamlet, Beowulf, and the like, have they reallygone the way of the literary buffalo? Contrary to the claimsof the conservative critics, James notes that Shakespeareand other members of the pantheon still have a strong presenceon Swarthmore syllabi. Fourteen of the 18 introductoryEnglish courses offered in the 1999–2000 course cataloginclude works by the Bard. By comparison, Toni Morrison,the Nobel Prize–winning author whose inclusion in theEnglish curriculum is decried by the NAS, is taught in just 2of the 18 and Zora Neale Hurston in 1. It is true, as the NAScharges, that studying Shakespeare is not required of Englishmajors, but as Williamson notes, nearly all majors do so atsome point in their Swarthmore career. Further deepeningthe department’s roots, Williamson’s survey course,“Beowulf to Milton,” covers the literature of Anglo-Saxon,Middle English, Renaissance, and 17th-century periods.Like other elite liberal arts colleges, Swarthmore hasn’tcrowded out the canonical authors. Rather, the College hassimply expanded the universe to accommodate newer writerswithout displacing the old. Excluding theater courses,the department offered just 24 courses in 1964; by this year,the number had grown to more than 100.The worthiness of newcomers like Morrison for a place inthat wider universe is another question, one that Williamson,the medievalist, answers passionately. The NAS andother conservative critics, he believes, “want to teach TheNorton Anthology from 30 years ago.” That many of the new-Please turn to page 69John Milton Anchee Min N. Scott Momaday Cherrie Moraga Sir Thomas More William Morris Toni Morrison Paul Muldoon Bharati MukherjeeFriedrich Nietzsche Flora Nwapa Flannery O’Connor Sharon Olds Eugene O'Neill Sembene Ousmane Sara Paretsky Marge Piercy Harold PinterLuigi Pirandello Alexander Pope Katherine Anne Porter Marcel Proust Thomas Pynchon Ann Radcliffe Ishmael Reed Adrienne RichSamuel Richardson Rainer Maria Rilke Tomas Rivera Mary Robinson Richard Rodriguez Salman Rushdie Joanna Russ Edward W. Said SapphireFerdinand de Saussure Olive Schreiner William Shakespeare Ntokaze Shange Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Percy Bysshe Shelley Julie ShikeguniSir Philip Sidney Leslie Silko Georg Simmel Susan Sontag Gary Soto Stephen Spender Edmund Spenser Olaf Stapledon Gertrude SteinWallace Stevens Sara Suleri Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey Jonathan Swift Torquato Tasso Drew Hayden Taylor Alfred, Lord Tennyson Ngugi Wa Thiong'oDylan Thomas Henry David Thoreau James Tiptree Jr. Leo Tolstoy John Kennedy Toole Jean Toomer Amos Tutuola Mark Twain Jules Verne VirgilGerald Vizenor Alice Walker Ian Watt Max Weber John Webster Rebecca Wells Nathanael West Edith Wharton Walt Whitman Oscar WildeRaymond Williams Terry Tempest Williams William Carlos Williams Barbara Wilson Jeanette Winterson Virginia Woolf Dorothy WordsworthWilliam Wordsworth Richard Wright Mary Wroth Sir Thomas Wyatt Wakako Yamauchi William Butler Yeats Ray A. Young BearS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 015

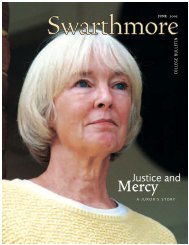

D I S T U R B I N GT H EP E A C ES W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NWhen I came toSwarthmore College inLounging on her sofa on a bright summer afternoon at Swarthmore’s Strath HavenCondominiums, the Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Professor Emerita of History KathrynMorgan grins and tells you she was not your typical Swarthmore professor. No sir,Morgan says, she was not typical at all. She was the first African-American woman tobe given tenure at Swarthmore; in fact, she was the first-ever African-American professorthe College hired.That was back in the early 1970s, and Morgan was a pioneer. A graduate of HowardUniversity, she completed her doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, the onlyAfrican American in the program. “It takes a toll on you at times, it does, being theonly one,” she says. “When I came to Swarthmore, it was because I thought the studentshere needed me—not just the black students, but I knew they needed anAfrican American on the faculty. I mean, there wasn’t even one!”Today, Swarthmore has a much better record on faculty diversity. Of the 166 fulltimeinstructional faculty, 25 are minorities, and 14 of those are African American (8with tenure). Among the faculty hired into tenure-track positions in the last 5 years,25 percent are people of color.The College’s Minority Scholars in Residence Program, begun in the 1980s by PresidentDavid Fraser, has been an important strategy for bringing more people of coloronto the faculty, says Provost Jennie Keith. Minority scholars are invited to be residenton campus during the period just before or after they receive a Ph.D. The programprovides time to complete a dissertation or launch postdoctoral research—alongwith the opportunity to teach in a liberal arts setting. Several minority scholars havejoined the permanent faculty after this program.But when Kathryn Morgan first came to Swarthmore, there were no such programs.She was breaking new ground. “I was not what they were used to,” she remembersabout her interview with Harrison Wright, then-chair of the department. “I was not awhite person in black skin. I was a black woman, OK? And they hired me! They wantedme to come! That speaks well of Swarthmore!” she says, with her trademarklaugh—half-giggle, half-cackle.For more than 20 years, Morgan taught Swarthmore students oral history, folklore,and folklife—an alternative view of history preserved in oral tradition, sometimeshanded down from generation to generation. During her childhood in Philadelphia,Morgan was raised on those kinds of stories of her own mother’s families and hergreat-grandmother, Caddy Buffers, who was born a slave. Morgan’s book Children ofStrangers: The Stories of a Black Family is an oral history of her mother’s family.“I heard stories all my life,” she says. “This is the history that people kept alive.We need a history in which we can see ourselves reflected.” Morgan paraphrases aquote from one of her favorite thinkers and writers, W.E.B. DuBois: “History that hasbeen accurately written is just a pinpoint in the sea of human experiences,” she says.“He called attention to the significance of oral traditions. We all have stories. Andthe thing I like about oral history is the fact that it’s ever changing. It’s not static.”To Morgan, and to many students who felt history come alive in her courses, oral1970, it was quite anaccident. I never heardof Swarthmore, eventhough I was raisedin Philadelphia.JIM GRAHAMO FR A C I S MA N O R A L H I S T O R Y O F T H E O R A L H I S T O R I A N K A T H R Y N M O R G A NBy Laura Markowitz ’8516

COURTESY OF KATHRYN MORGANhistory is the deepest kind of poetry. Personal accounts of struggle and wisdom andtriumph against the backdrop of larger events—wars, social movements, and economicchanges—reveal the essence of humanity, says Morgan. “It is absolutely beautifulbecause it reveals what people know in their souls. So many academics are concernedwith objective truths, but if they’re really interested in where ideas come from, theywould also be interested in oral history,” and then she shakes a finger at you andlaughs again, “You know exactly what I’m talking about!”This is Kathryn Morgan’s story about racism as she experienced it at SwarthmoreCollege. As she will tell you about any oral history, even her own, “This is my story. Iam speaking for only myself as I perceived it.”“ WhenI was a little girl—I wasabout 10 years old because Iknow that my feet didn’t touchthe floor when I sat in a chair—we hadthis movie house down the street fromus that was all white, and they madeblack children sit up in what wascalled the “nigger gallery.” This wasthe late 1930s in Philadelphia. Mymother said it was wrong, and shewouldn’t let us go to the movies onSaturday, which we thought was a punishmentfor something that we hadn’tdone. So one day, my mother, tired ofme standing by the window, looking alldreary and crying because I couldn’tgo to the movies—I didn’t understandthat she didn’t want us to sit up in thenigger section—so she said, “OK. Youwant to go to the movies? I’m going totake you to the movies!”Now, my mother looked white. Shehad blue eyes and light hair and whiteskin, so we had a problem every timewe went out together. Anyway, shetook me to the movies and she said,“There’s one condition. You’re notgoing to sit up in the ‘nigger’ gallery.“YOU COULDN’T BE ACOWARD WITHCHILDREN IN THOSEDAYS BECAUSE IFYOU WERE, YOUWOULD BRING UPCOWARDLY CHILDREN.”LEFT: PROFESSOR EMERITA OF HISTORYKATHRYN MORGAN. ABOVE: MORGAN AND HERAUNT ADELINE IN PHILADELPHIA, CA. 1930.You’re going to sit down in the frontwith the white people.” That was allright with me because I thought shewas going to go with me. But she saidto me—and this is a very importantlesson—she said, “Go in there, and yousit there in the front, and don’t youmove. Don’t come home. Don’t do anything.Don’t you move.” My motherwas worried about what was going tohappen to me and my personality if Iwas discriminated against and acceptedthat I was inferior and all the nonsensethat comes along with racism.So there I was, at the movies andterrified. I remember the picture; it wasShirley Temple and some little somethingor other she was doing withBojangles. Yes. She was tap dancing upthe steps. I remember that even today.So then a little usher came down, andhe said to me, “Nigger, you’re not supposedto be here. You’re supposed tobe upstairs.”And I said, “I can’t move becausemy mama told me not to move.”He said, “I’m going to get the policeon you. You’re breaking the law.”S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 017

S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I NWell, I was so scared that he’d putme out, but I couldn’t go upstairs [tothe nigger gallery] because my mamatold me not to go upstairs. So hepushed me out the front door, and Iran home. And she was standing in thekitchen cooking. I never will forget this.She said, “What are you doing home?You wanted to go to the movies!” I toldher what happened. She said, “Allright. Where’s your money? Did youget your money back?” I didn’t get mymoney back. They just put me out ofthe movies, right? She said, “All right.We’re going back, and we’re going toget your money. We’re going back tothat movie. Now I’m going to sit downstairswith you,” she said. Well, wewent back to the movies, and she wentin front of me instead of next to me.The little man didn’t know that shewas my mother. He thought I was tryingto get back into the white sectionagain by myself. So he grabbed me. Hesaid, “Sister,” and he pulled me back,and she turned on him. She said, “Doesshe look like your sister to you?” Theboy was so shocked. What’s this whitewoman doing here? He was so upsetthat we went right on down in thewhite section and sat again, my motherand I, both of us. We didn’t know thathe had gone to call the police. Shesaid, “I’m leaving, and you are sitting.”She left me there. So when thepolice came, I was crying. I can stillremember the little tears. I wasn’t evenlooking at the movie. I was looking atmy feet and praying that I would livelong enough so that my feet one daywould hit the ground [laughing]! Thepoliceman came down. I rememberthis as clear as if it was yesterday. Hehad really red hair, brilliant red hair,because that’s all I remember. He saidto me, “Little girl, we have a report thatyou’re disturbing the peace. Are youdisturbing the peace?”I said, “I don’t know. My mama toldme to do this. I don’t know.”He said, “Well, look. This little girl isdisturbing the peace. I’m going to haveto sit down here with her to see thatshe doesn’t disturb the peace.” Peoplejust left empty seats all around. So hetook off his cap, and he sat right nextto me. He was sitting there, and hesaid, “Little girl, are you all right? Areyou disturbing the peace?” I wasn’tlooking at the movies. I was praying. Iwanted that movie to end so badly. I“I THOUGHT, ‘OHGOD. A POLICEMANWALKING ME HOME!WHAT’S MAMA GOINGTO SAY?’ I WASN’TSCARED OF THEPOLICE, BUT I WASSCARED TO DEATH OFMAMA.”KATHRYN MORGAN FIRST TAUGHT AT <strong>SWARTHMORE</strong>IN 1970—THE FIRST AFRICAN AMERICAN ON THEFACULTY. DESPITE HER DEGREES FROM HOWARDUNIVERSITY AND THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVA-NIA, SHE SAYS SHE FELT “MORE IN COMMON WITHTHE BLACK PEOPLE WHO CAME TO CLEAN, COOK,AND SERVE” AT THE COLLEGE.JIM GRAHAMtell you, I wanted that movie to end.When it finally ended, he said, “Littlegirl, I’m going to walk you home.”I thought, “Oh, God. A policemanwalking me home! What’s Mama goingto say? I’ll be in all kinds of trouble.” Iwasn’t scared of the police, but I wasscared to death of Mama.He said, “Do you want an ice creamcone?”I said, “Yes.” So he bought me an icecream cone. I was too scared to eat it.So it was dripping all down. I said,“Would you do me a favor?”He said, “What?”I said, “Don’t walk me home!”I ran home with this melting icecream cone, and my mother was still inthe kitchen. She turned around, andshe said, “How are you?” or somethinglike that. I don’t remember exactly, butI know she said, “Where did you getthat ice cream cone?”I said, “The cop bought it for me,”or something like that.She took the ice cream cone andthrew it away. She said, “There are certaintimes in life when you must disturbthe peace. You must disturb thepeace of racism. You must disturb thepeace. You must never, ever be peacefulin the fight.” You couldn’t be a cowardwith children in those daysbecause if you were, you would bringup cowardly children, and you had toremember that there were certainthings worth dying for. So I learned at10 years old to disturb the peace ofracism, and I will continue doing so foras long as I live.Years later, I wrote my book [an oralhistory] about my mother’s family, theGordon family. My mother was a Southernmigrant in Philadelphia. My mothernurtured me on stories of my grandmotherand especially my great-grandmother,Caddy. I loved them, and theywere my inspiration. I would alwayssay, “What would Caddy do in a situationlike this?” I would tell myself,“This situation, no matter how bad itis, could not possibly be as bad asbeing kidnapped when you were 8years old and sold into slavery.”When I came to Swarthmore Collegein 1970, it was quite an accident. Inever heard of Swarthmore, eventhough I was raised in Philadel-phia. Ihad a master’s from Howard, and Iwent to Penn for another master’s and18

MARTIN NATVIGa Ph.D. When the semester started, aprofessor came to a department meeting.He said, “We have the best peoplein our class. They come from the highestacademic circles. We have studentsfrom Harvard, and we have studentsfrom Princeton. So, therefore, you allare in a wonderful group, with theexception of you,” and he pointed tome—the only black person in theroom-—and said, “I understand youhave come from an inferior educationalbackground.” I’m not lying to you.He said that. He said, “You have comefrom an inferior educational background,so we’ll make exceptions inyour case.” It was 1966. I was the onlyAfrican American in the entire program.I sat there, and I said to myself, “I’mnot going to let him get away withthis— even if I get thrown out of graduateschool.” And I said to myself, “Disturbit! Disturb it! Because you can’t lethim get away with it! Disturb it! Disturbit! Because you can’t allow it!” So Isaid, “I’ve only taken one course here,but I agree with you. That course(which he taught) was totally inferiorto what I have been used to.”He said, “I’m sorry. I’m sorry.” Doyou know, that man turned out to be“WHAT I RESPECTED,WHAT GOT METHROUGH, WERE THESTUDENTS ... HOWBRIGHT THEY WEREAND HOW THEYTHOUGHT. I ALSOWANTED TO BE HEREFOR THE BLACKSTUDENTS.”DENIED TENURE, MORGAN WENT TO COURT,JOINING A DISCRIMINATION SUIT BROUGHT BYSEVERAL FEMALE EMPLOYEES. BEFORE THEVERDICT, THE COLLEGE CHANGED ITS MIND.my best friend in graduate school? Hereally got me through. He said he wasyoung. He was inexperienced, and hehad a graduate school class that wasoverwhelming for him. And he didn’tknow what else to do. He was totallyinsensitive. He didn’t know, and hebecame my best friend. He’s dead now,but I will never forget him.So I had gotten a Danforth Fellowship,along with a white woman. Webecame friends, and she lived inSwarthmore. I had never heard ofSwarthmore. She had never known anyAfrican Americans. Anyway, she calledme up one night. She said, “You’regoing to kill me.”I said, “Why? What have you done?”She said, “I’ve dropped your name.Swarthmore College is a wonderful college.It’s very unique, and people aredying to go there. Well, they were sayingthey couldn’t find any AfricanAmericans qualified to teach at SwarthmoreCollege. So I dropped your name,and they will be in touch with you.”I wanted to teach, but my ambitionwas to go to Lincoln University, a blackuniversity right up here in Pennsylvania,not too far from Swarthmore. Ithought, “If they can’t find any qualifiedAfrican Americans, then I don’tS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 019

“SO MANYACADEMICS ARECONCERNED WITHOBJECTIVE TRUTHS,BUT IF THEY’REREALLY INTERESTEDIN WHERE IDEASCOME FROM, THEYWOULD ALSO BEINTERESTED IN ORALHISTORY.”S W A R T H M O R E C O L L E G E B U L L E T I Nwant to go there either!” And then I forgotall about the telephone conversation.Some time later, I was looking at television,and there came a news storyabout black students who had takenover the president’s office at a college.I said, “Where is that? Where is that?”Turns out it was at Swarthmore College.I said, “I don’t believe this! That’sreally cool!” So when I got the telephonecall to come to Swarthmore College,I said, “I’m gonna go!”I had nothing to wear that lookedprofessional; I didn’t have any stockingsbecause I never wore stockings.But I borrowed a pair of my daughter’sstockings—-they were sort of pinkish—and some kind of presentable shoes.So I showed up in that, and I rememberthe interview process. One of the peopleon the interview committee said tome, “I know more about Negroes thanmost people.”I said, “Really?”She said, “Yes, and these studentshere will not even speak to me, won’teven talk with us! They took over thePresident’s Office, and you know ifA FEMALE COLLEAGUE WARNED MORGAN NOT TOWEAR EARRINGS, LONG DRESSES, AND SANDALS.MORGAN REPLIED, “LOOK, THIS IS ME....IF YOU WANT BLACK PEOPLE WHO LOOK LIKEWHITE PEOPLE, WHO ACT LIKE WHITE PEOPLE,GET A WHITE PERSON.... IF YOU’RE LOOKING FORDIVERSITY, YOU WANT THE REAL THING.”push came to shove, they would losethe battle.”So I said, “Yes, I bet they would.”She said, “Now what do you think ofMalcolm X?”I said, “Well, the one thing I rememberabout Malcolm X, he talked aboutreciprocal bleeding—if you hit me, I’mgoing to hit you back by any meansnecessary. So maybe these studentsaren’t talking to you. Maybe you couldMARTIN NATVIG20

throw them out, and maybe you wouldwin. But I’ll tell you, there will be somereciprocal bleeding up here.”She said, “The interview is over.”The black students asked me why Iwanted to teach here. They weresmart. I said I didn’t particularly wantto come until I had seen them on television,and I thought they neededsomebody like me. That really waswhy I came to Swarthmore. It was1970, there still wasn’t one African-American professor on the faculty.I fully expected not to get an offer.Before I left that day, I said to HarrisonWright, “You’ve got some problems uphere.” He was a fair person. I told him Iwasn’t interested in the position. But Iwas also thinking Swarthmore was themost beautiful campus I had ever seen.Harrison said, “I really do understand.”He knew if he offered me the position Iwouldn’t take it. So I went home andforgot about Swarthmore College. ThenI got a telephone call. Harrison Wrighthad asked the head of the Black Students’Association to offer me the positionin the History Department.I asked, “Well, why didn’t he call mehimself?”She said, “Because he felt that if hecalled you, you wouldn’t accept theposition, but if we called you, youmight accept the position.”I realized I was probably the firstand only African-American professorthe College had ever hired in 106 years!Now, they had a couple of African professorsup here who, if they didn’tbehave, they could send back toAfrica, but they couldn’t send me backto Philly. You understand? There’s adifference [laughing]! It’s to their creditthat they wanted me—because I didn’tpull any punches. I was letting themknow I was someone who would disturbthe peace of racism. And theyoffered me the position. How do I knowwhy? There were some very radicalpeople up here at that time. I had alliesfrom the very beginning.I taught one course at Swarthmorein 1970. Then, I accepted a position inthe English Department at the Universityof Delaware and went back toSwarthmore as an assistant professorwith a three-year appointment. Theytold me it was not sure I would gettenure with my next appointment, andI accepted that. I said yes because Ididn’t know what I was doing. I had noidea how very political and very racistSwarthmore could be. Yes, some peopleat Swarthmore would not believehow racist it really is. Yes, I’m saying it,yes. They do not understand thedynamics of racism, how deep it goes,and how I understand it on an entirelydifferent level.For example, when I moved into myapartment [30 years ago], I was theonly African American in the building[Strath Haven Condominiums] and stilltoday there is only one other African-American couple living here. The swimclub in town did not allow blacks inthe pool when I first moved here, andthey had to desegregate that. Theseare the kinds of things most of thewhite students and faculty never haveto put up with, but we African Americansknow.ONE OF THE PEOPLEON THE INTERVIEWCOMMITTEE SAID TOME, “I KNOW MOREABOUT NEGROESTHAN MOST PEOPLE.”I SAID, “REALLY?”There were also other differences.My people don’t come from money,but several of my colleagues in the HistoryDepartment had family money. Ihad more in common with the blackpeople who came to clean, cook, andserve at Swarthmore College. Butwhen I first came to Swarthmore andwas looking for black community, Ifound that they didn’t want to be tooclose to me. Some of them were makingbelow minimum wage after 25years, you see? So I joined a group offaculty who were trying to get themunionized so they could get bettersalaries. The attempt failed becausethe black workers voted it down. Theywere afraid they were going to losetheir jobs. But some of those peoplereally took pride in everything I did.One, in particular, would come out atgraduation and say, “Kathryn, yougonna wear your gown?” I would do itbecause it mattered to her. Most ofthem I had deep respect for, and theyhad deep respect for me.Being African American at Swarthmore,you almost have to fight foryour identity every single day. For me,as a professor, it’s different from a studentbecause a student has other studentsto relate to. I had no AfricanAmerican colleagues until Jerry Woodwas also hired in the History Departmentsoon after I came. And thenChuck James came into the EnglishDepartment. Both of them are wonderful,talented people, and I was glad tohave them here.So I taught, and my courses werepopular. But there was politics inthe department. Some professors werehostile because they thought oral historyand folklore were not “real” history.They even told students—-whitestudents—-not to take my coursesbecause they weren’t historically valid,and they wouldn’t learn anything.Some students came and disrespectedthe whole thing until they began to listen,and then they grew to love oralhistory and folklore. But it was hard,day by day, to be in a departmentwhere some of your colleagues lookeddown on your field.There were other issues. One femalecolleague, who was the most sincereand nice, told me, “I want you to gettenure in the worst way. I’m going totell you something. Don’t wear thoselong earrings to work, and don’t wearyour hair like that.” I had a naturalhairstyle. “And don’t wear those dressesthat you wear, those long dresses,and those sandals. We don’t wear sandals.”I said, “Look. This is me. This is me,and I am going to be like I am. If youwant black people who look like whitepeople, who act like white people, geta white person! You don’t need a carboncopy of a white person. If you’relooking for diversity, you want the realS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 021