MUNINN

MUNINN - Grand View University

MUNINN - Grand View University

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>MUNINN</strong>Journal of HistoryVolume 22013ISSN 2167-8391

The Story of <strong>MUNINN</strong>(MOON · in) and commonly (MYEW · nin)Grand View University, with Vikings as our mascots, is thefinal university celebrating its Danish-American roots.The Viking god, Odinn (or Woden), had two ravens that hesent forth to earth: Huginn who reported on human thought or intentions, and Muninnwho reported the memory of human events and actions. Additionally, the Vikings wereguided by ravens on their voyages by releasing an under-fed raven that wouldinstinctively sore high into the sky in search of land by which the Viking longshipcould navigate. Viking longships often displayed the raven flag seen above in theirmany raids.“I fear that Huginn may not return, yet more anxious am I for Muninn.” -OdinnGrimnismál of the Poetic Edda, Codex Regius, c. 1270<strong>MUNINN</strong>: Journal of History is a journal of the Grand View University HistoryDepartment that welcomes article and book review submissions from its undergraduatestudents, alumni, faculty, and friends of the journal and department. All periods andsubjects of history are welcome. There is special interest in article submissions thatutilize either the Danish-American records of the Grand View University Archive inDes Moines, Iowa, or the Danish-American Archive and Library in Blair, Nebraska.All undergraduate article submissions will be sent to referees for recommendation ofpublication. Editors will do their best to match article submissions with referees whohave expertise or insights in those fields. Book reviews may be of new history,important historiography, and novels or non-fiction that reveal the social context of anera or people. Short essays are also considered for publication. Submission guidelinesare inside the back cover of this journal.Disclaimer: The opinions and accuracy of facts in the articles and book reviews of<strong>MUNINN</strong> are the sole responsibility of the contributors and do not represent thejournal, its referees, the History Department, or Grand View University. This journalaccepts no legal responsibility for errors or omissions. The reader’s critical judgmentmust be exercised with care.Permission: All rights reserved. The use of the <strong>MUNINN</strong> logo or the seal of GrandView University is expressly prohibited. For permission to reproduce an article, bookreview, or advertisement from this journal beyond traditional academic fair use, pleasecontact mplowman@grandview.eduAcknowledgments: The <strong>MUNINN</strong> staff thanks the Student Viking Council for fundingthis journal with student publication fees and thanks the History Department forfunding postage.Printed by Carter Printing Company, 1739 East Grand Ave, Des Moines, Iowa 50316

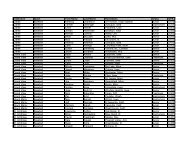

<strong>MUNINN</strong>Journal of HistoryVolume 2, 2013Refereed ArticlesChurchill amd the Atlantic Charter (1941): The SpecialRelationship with FDR and the United StatesGabby (Detrick) Breheny 1Lincoln v. Douglas: The Illinois Senatorial Debates of 1858Kayla (Gaskill) Jacobson and Austin Bittner 10The Treaty of London (1838): Its Reinterpretation andImpact on the Outbreak and Conclusion of the First World WarMicheal Collins 25Analyzing the Role of General Fellgiebel in the July 1944Plot to Kill HitlerDanika Stadtlander 33Ireland’s 1937 Constitution: De Valera’s Hold on Divorce,Abortion, and IrishnessSadie Fisher 41Short EssaysThe Origins of Al-Qaeda and the War on TerrorismHeidi Torkelson 51Hamas: One Man’s Terrorst is Another Man’s Freedom FighterQuinton Clark 57Book Reviews 65Conferences, Calls for Papers, and Advertisements 77History DepartmentJensen Hall, Grand View University1200 Grandview AvenueDes Moines, Iowa 50316

Referees for 2012-2013 article submissions:Professor Nicole Anslover, University of Indiana Northwest20 th Century America, US Foreign PolicyProfessor Douglas Biggs, University of Nebraska-KearneyMedieval and Military History, Associate Dean of Natural & Social SciencesProfessor Kevin Gannon, Grand View UniversityColonial & 19 th Century America, Latin AmericaProfessor Kurt Hackemer, University of South Dakota19 th Century American Military HistoryProfessor Mary Lyons-Carmona, University of Nebraska-OmahaModern Irish, 20 th Century America, Child Labor, Migrant Labor-Commercialized Agriculture HistoryJim Rogers, University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MinnesotaManaging Director of the Center for Irish StudiesManaging Editor of the New Hibernia Review.Evelyn Taylor, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, State of IllinoisEditor of the Journal of Illinois HistoryCopyeditor of the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln AssociationProfessor Evan Thomas, Grand View UniversityContemporary America and World, Modern East Asia.Professor Katharina Tumpek-Kjellmark, Grand View UniversityModern Europe, Germany, Holocaust, Women’s History.Mike Vogt, Iowa Gold Star Military Museum, Camp Dodge-Army National GuardMuseum CuratorThe <strong>MUNINN</strong> staff would like to thank all of the referees for their time in making thisjournal successful and academically rigorous. Many of the referees reviewed multiplesubmissions this year.Editor in Chief:Editor:Research:Graphic Design:Faculty & Managing Editor:Christopher MillerAustin BittnerJoelle DietrickPaige KlecknerProfessor Matthew Plowman

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Churchill and the Atlantic Charter (1941):The Special Relationship with FDR and the United StatesGabby (Detrick) BrehenyGrand View UniversityThe impact of the Atlantic Charter, as a joint declaration byBritish Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) and USPresident Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) on August 14, 1941, shookthe world and global order during and long after the Second WorldWar. Although Britain had for a long time extended home rule to someof the white settler colonies such as Canada, Australia, and SouthAfrica, few expected Britain to be drawn into the journey of releasingthe Empire itself as the sacrifice for saving the kingdom of the BritishIsles. Why did Churchill agree to the Charter? By summer of 1941,Germany had taken nearly all of western and central Europe and had afull invasion of the Soviet Union progressing towards Leningrad,Smolensk, and Kiev. Britain had to rush forces to Egypt to defend itsprotectorates in the Middle East from Italian Libya. By the time of theAtlantic Charter, there was also a threat from Japan in the Pacific.Imperial Japan controlled the most populous parts of China and hadtaken French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos), thereforethreatening British control over Burma, India, Singapore, and HongKong. Why did FDR agree to the Charter? Although the President wassuccessful in helping Britain through some war matériel, the AmericaFirst Committee was a strong lobbying force keeping American out ofthe war. FDR needed the Atlantic Charter to win the propagandabattle. Unlike WWI that expanded empires, the Atlantic Charterpromised real progress on self-government, freedom of the seas,reduction of trade restrictions, and global cooperation. DespiteChurchill making statements just weeks after signing the AtlanticCharter that it did not directly apply to all of Britain’s colonies, it wasdifficult for Britain to maintain a minimalist interpretation once theAllies, who increasingly called themselves the United Nations, madepledges to the Charter in their “Declaration of United Nations” onJanuary 1, 1942. 1 Churchill was locked into this gamble to save the1“The Governments signatory hereto, having subscribed to a common program ofpurposes and principles embodied in the Joint Declaration of the President of the UnitedStates of America and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain andNorthern Ireland dated August 14, 1941, known as the Atlantic Charter,” in Declarationby the United Nations, 1 January 1942. The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History,and Diplomacy, Lillion Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School.1

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Kingdom by what most considered an eventual release of the Empire. 2All of this was made possible by the relationship and friendshipbetween Churchill and Roosevelt; without it, the world may not haveseen the same outcomes of the war. The Anglo-American alliance ofWorld War I was not as deep as the “special relationship” that thesetwo leaders built during World War II, which carries on today.Although Britons were exposed to more and more antiimperialism,especially among their left wing parties, after conflicts andcomplications in Ireland, South Africa, Afghanistan, Iraq, andPalestine, during and after World War I, the majority of Britons simplytook the existence of the Empire for granted and even consideredhaving an Empire as being a Briton. Certainly this was the case forChurchill, who never fully grasped the potential implications of thisagreement if it were taken to its fullest measure. 3 Usually thearticulated common outcome is the focus an agreement, but in the caseof the Atlantic Charter much value was placed upon the cooperationitself. The special personal relationship of Churchill and Rooseveltbeing made into a special relationship between their nations was theimmediate outcome. 4To fully appreciate this, one needs to understand how thepersonal relationship between Roosevelt and Churchill began. As faras we know from declassified documents, they exchanged at least 1,700letters, messages, and telegrams in the five and a half years between theoutbreak of the war and Roosevelt’s death in 1945. The President andPrime Minister also spent over 120 days together in person during thewar, with the meeting for the Atlantic Charter being their first officialface-to-face opportunity. 5 The written correspondence between thembegan a year earlier, even before Churchill was prime minister. InAvalon.law.yale.edu/20 th _century/decade03.asp (Accessed September 4, 2013) Thedeclaration was signed by the US, UK, USSR, China, Australia, New Zealand, SouthAfrica, Canada, India, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala,Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, as well as the governments-in-exile of AxisoccupiedCzechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Poland,and Yugoslavia. Mexico, Philippines, Ethiopia signed later in 1942. Iraq, Iran, Brazil,and Bolivia signed in 1943. Liberia, France, and Ecuador signed in 1944. Peru, Chile,Paraguay, Venezuela, Uruguay, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Syria signedin 1945.2By the end of the war, Churchill’s Conservative government lost to the British LabourParty under Clement Attlee, who immediately embraced the maximalist or anti-imperialinterpretation of the Atlantic Charter.3It should be noted that Britain made conflicting promises to Jews, Arabs, and the Frenchduring World War I in order to secure their support, so Churchill may have felt somefreedom to minimize the Atlantic Charter.4Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, Roosevelt and Churchill: Their SecretWartime Correspondence. Edited by Francis L Loewenheim, Harold D Langley andManfred Jonas (New York: Saturday Review Press/E.P. Dutton & Co, 1975), 3.5Churchill and Roosevelt, 4. Churchill was head of the Royal Navy during WWI butstepped-down after the failure of the Battle of Gallipoli.2

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Army one-fourth of the way to Paris.Churchill understood FDR’s political difficulty with Congressand public opinion over the official position of neutrality, but requesteddirect American aid anyway. In the May 15 th letter: “Mr. President, thevoice and force of the United States may count for nothing if withheldtoo long…. All I ask now is that you should proclaim nonbelligerency,which would mean that you would help us with everything short ofactually engaging in armed forces” 9 The Prime Minister requested aloan of forty or fifty of America’s older destroyers to help them whilethey awaited the construction of their own that were begun at thebeginning of the war. Churchill also proposed an advance on “severalhundred of the latest types of aircraft, of which you are now gettingdelivery,” i.e. have the US Air Corps send their own planes to Britainimmediately in exchange for planes still being built in Americanfactories for the RAF. There were more requests, all of which had asolution by Churchill as to repayment. With the situation desperate inEurope, Churchill needed all of the resources he could musterimmediately. Churchill later recalled: “No man ever wooed a womanas I wooed that man for England’s sake.” 10 Roosevelt responded thevery next day: “I have just received your message and I am sure it isunnecessary for me to say that I am most happy to continue our privatecorrespondence as we have in the past. I am, of course, giving everypossible consideration to the suggestions made in your message. I shalltake up your specific proposals one by one.” 11 Roosevelt described thedifficulties with Congress for such actions, but said he would make hisbest efforts. The US Ambassador to Britain, Joseph Kennedy (1888-1969, father of JFK), further pressured FDR by indicating that Britainmight surrender at any time due to the fall of France in June and theintensified Battle for Britain happening in the skies. On September 2,1940, FDR gave the Royal Navy fifty US destroyers in return for USbases or airfield rights on many British territories in the Atlantic. FDRalso went around Congress and the neutrality laws when he sent largeamounts of ammunition to the British Army that he claimed wereobsolete. This was risky just two months before a presidential electionand it was not until February 1941, three months after the election, thatGallup indicated a majority of Americans were in favor of aid toBritain.The Axis powers were seeing an apex of power in Europe in1941 as Britain stood alone against them until the Axis invasion of theSoviet Union in June. 12 In a matter of weeks, German blitzkrieg gained9Churchill and Roosevelt, 94.10Carlo d’Este, Warlord: A Life of Winston Churchill at War, 1874-1945 (New York:HarperCollins, 2008), 497.11Churchill and Roosevelt, 95.12U.S. Department of State, Making the Peace Treaties: 1941-1947 (Washington D.C.:4

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)an area greater than France and the Low Countries combined, as Sovietforces retreated to the defenses of Leningrad, Smolensk, and Kiev.While the Axis invasion of the USSR took much of the direct threataway from the British Isles, the British had taken a pounding from theGerman Luftwaffe and British supply lanes were deeply constrained byGerman U-boats. Britain was exhausted. Also, there were British fearsthat potential American aid might be diverted to the more activeEastern Front in Russia. 13 Churchill and FDR planned on having aprivate meeting in person. On July 25, 1941, Churchill wrote toRoosevelt:Cabinet has approved my leaving. Am arranging if convenient to youto sail August 4 th , meeting you some time 8 th -9 th -10 th . Actual secretrendezvous need not be settled till later. Admiralty will propose detailsthrough usual channels.Am bringing First Sea Lord Admiral Pound, CIGS, Dill, and ViceChief of Air Staff Freeman. Am looking forward enormously to ourtalks, which many be of service to the future.” 14The meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt on August 9-12, 1941, isconsidered the first wartime conference between the two. They draftedthe Atlantic Charter in a series of meetings aboard the British battleshipHMS Prince of Wales and the United States cruiser USS Augusta inNewfoundland’s Placentia Bay. The charter was released to the publicon August 14, 1941. The United States and the United Kingdom basedtheir hopes for a better future for the world on the following eightprinciples:1) No material gains out of the war.2) No territorial changes, except those which are desired by the peoplesconcerned.3) All peoples to have the right to choose their own form of government.4) All peoples who were forcibly deprived of sovereign rights and selfgovernmentto havethose losses restored.5) A peace guaranteeing the safety of all nations and enabling the peoplesof those nationsto be free from fear and want.6) A wider and permanent system of general security.7) All nations to have access, on equal terms, to the trade and raw materialsof the world.8) Fullest economic collaboration between all nations toward improvedlabor standards,economic advancement, and social security. 15United States Government Printing Office, 1947), 1.13Paul Dukes, "The Rise and Fall of the Big Three," History Review no. 52 (September2005): 42-47. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed April 16, 2012)14Churchill and Roosevelt, 152.5

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)They each had some explaining to do back home—especially PrimeMinister Churchill over the third and fourth principles that maximalistsinterpreted as decolonization. The very idea of Britain giving theEmpire not only created lamentations over ground held for decades orcenturies through the blood of Britons, but also created consternationover what Britons would be in the future without an empire. Wouldthey still be just as great? The Charter plunged Britons into uncertaintyand fear over the future even if they were victorious over the Axis.Churchill sought to alleviate these fears and argue for a minimalistinterpretation that left the Empire intact, as he reported to the House ofCommons:At the Atlantic meeting we had in mind primarily the extension of thesovereignty, self-government, and national life of the states and nationsof Europe now under the Nazi yoke and the principles which shouldgovern any alterations in the territorial boundaries of countries whichmay have to be made. That is quite a separate problem from theprogressive evolution of the self-governing institutions in regions whosepeoples owe allegiance to the British crown. We have made declarationson these matters which are complete in themselves, free from ambiguityand related to the conditions and circumstances of the territories andpeoples affected. They will be found to be entirely in harmony with theconception of freedom and justice which inspire the joint declaration. 16A charity worker in London, Vere Hodgson (1901-1979), expressed thesentiment of most Britons that she expected a declaration of an Anglo-American alliance and was disappointed that the Charter was simply aset of war objectives that were “all very laudable in themselves—theonly difficulty will be in carrying them out.” Hodgson describedherself as depressed over the matter. This feeling was common.Churchill sent a cable to FDR’s Lend-Lease negotiator, Harry Hopkins:“I ought to tell you that there has been a wave of depression through[the] cabinet and other informed circles here about [the] President’smany assurances about no commitments and no closer to war….If 1942opens with Russia knocked out and Britain left again alone, all kinds ofdangers may arise….Should be grateful if you could give me any sortof hope.” 17By comparison, FDR’s maximalist interpretation of the chartergained ground in America as the war progressed, especially afterAmerica’s entry after Pearl Harbor in December 1941. On February15U.S. State Department, 2.16Committee on Africa, the War, and Peace Aims, Phelps Stokes Fund, The AtlanticCharter and Africa from an American Standpoint (New York: Haddon Craftsmen, Inc,1942), 31.17Max Hastings, Winston's War: Churchill, 1940-1945 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,2010), 170. Editor’s note: Hastings used a well-known diary of Vere Hodgson that isused by many historians to demonstrate the common Briton’s view of the war.6

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)23, 1942, President Roosevelt informed the American public in one ofhis radio broadcasts that the Atlantic Charter applied to every nation orcolony: “The Atlantic Charter applies not only to parts of the worldthat border the Atlantic, but to the whole world; disarmament ofaggressors, self-determination of nations and peoples and the fourfreedoms: Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom fromwant, and freedom from fear.” 18 Questions and concerns surfacedimmediately regarding its universal application, since the US had itsown protectorates including the Philippines that were occupied byJapan since December 1941. In 1942-43, the US was already workingwith Vietnamese and Filipino rebels against Japanese forces on thepremise that their independence would be the result of winning thewar. 19Whether or not FDR wanted to avoid further complications inthe special relationship with Churchill, the president allowed otherpoliticians to take the leading voice for his maximalist vision for theAtlantic Charter. Some even saw the charter as an opportunity toextend statehood to American territories such as Hawaii and PuertoRico. On February 13, 1943, New York Congressman Joseph ClarkBaldwin (1897-1957) gave a speech on the implementation of theAtlantic Charter in front of the Foreign Policy Association ofPennsylvania, and said:Probably at no time in the history of this country has our Congressfaced so grave a responsibility as confronts it today. In theRevolutionary War we fought to create the Union. In the Civil War,we fought to preserve the Union, and in this war, as in the last war,we are, in my opinion, fighting to extend the Union. 20Baldwin emphasized that he was not an imperialist, and even suggestedthat the United Nations, although only a name for the alliance againstthe Axis at this point, might become another mechanism towards globalunity and democracy. By the time of Baldwin’s speech, twenty-ninenations had signed the Atlantic Charter since August 14, 1941.Congressman Baldwin stressed the necessity and centrality ofdemocracy as the main principle of the Charter and that democracyneeded to be made efficient and available to these new states thatwould emerge: “Democracy must be streamlined if it is to hold itsown. [Yet it need not] lose one iota of its democratic effectiveness in18Committee on Africa, 30.19The Philippines observed their independence from the US on the Fourth of July, 1946.The French ignored FDR and reoccupied Vietnam and fought a bitter colonial war, 1945-54.20Joseph Clark Baldwin, "Implementing the Atlantic Charter," Vital Speeches of the Day9, no. 12 (April 1943): 380. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed April 16,2012)7

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)the process.” He said that Congress needed to work together andquickly so that the Atlantic Charter did not lose its opportunity ormomentum. Baldwin also made the point that the Atlantic Charter wasthe only document signed by the United Nations that contained any sortof concrete peace aims. 21 Other Americans continued to press theCharter’s outcomes deeper into the war, such as New York MayorFiorello LaGuardia (1882-1947), who gave a speech at the OpeningCeremonies of Free World House just days before the Battle ofNormandy in June 1944. La Guardia took it upon himself to explain thepsychology of Britain’s agreement to the Charter:I am going to talk this evening about the Atlantic Charter. Whenmen are in great sorrow they speak from the innermost of their soul.When men are in great danger they think clearly and act unselfishlyfor their own safety as well as that of others…. While there were somepeople in our country who perhaps could not or would not evaluateproperly and fully on our own situation and our common interest withGreat Britain, and the inevitable attack which would follow a Nazivictory in Europe, the military and naval minds of our country wereworking frantically to utilize every second of time while our Presidentwas pleading and begging Congress for necessary appropriations.” 22La Guardia emphasized the desperate situation of the British military in1940 and that without this US aid to Britain in 1940, Britain wouldhave fallen—and the Germans would be off the American coast with aforeign threat not seen since the War of 1812. LaGuardia said that theAtlantic Charter was a pledge on the parts of the United States andGreat Britain that they would do whatever was necessary to fight theAxis and that it was a promise of hope to the rest of the world. 23Both Churchill and FDR had a healthy personal sense of“historical purposefulness.” 24 Churchill needed to save his Britain,which had not been so threatened by invasion in centuries. For Britain,the central aim was simply the survival of the United Kingdom. Bycontrast, Roosevelt wanted to save and arguably spread democracy—even making it a central aim of the war. 25 Despite their competingminimalist and maximalist positions over the Atlantic Charter, thespecial relationship was sustained between these men and even grew tonational levels. Even today we hear of this special relationshipbetween the US and UK in matter of foreign policy. As early as 1940,Churchill had little doubt as to the success that could be gained if he21Baldwin, 381-382.22F. H. LaGuardia, "Interpreting the Atlantic Charter," Vital Speeches of the Day 10, no.18 (July 1944): 555. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed April 16, 2012)23LaGuardia, 555.24Joseph P. Lash, The Partnership that Saved the West: Roosevelt and Churchill, 1939-1941 (New York: W.W. Norton., 1976), 179.25LaGuardia, 556.8

Churchill and the Atlantic Charter <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)became prime minister and had close relations with the President of theUnited States: “I wish to be Prime Minister and in close and dailycommunication by telephone with the President of the United States.There is nothing we could not do if we were together.” 26 He believedan Anglo-American alliance to be the winning force. If we see theAtlantic Charter as the beginning of this special relationship, we maybe left disappointed in its outcomes at least in the short-term as Britainfought many wars to keep its empire in the 1940s and early 1950s fromAden to Malaya, before embracing decolonization in the late 1950s and1960s. The US also retreated from its maximalist position on selfdeterminationwhen so many of the anti-colonial rebels turned to theSoviet Union for assistance and promised socialist or communist formsof government. Ironically, the US and the UK exchanged their originalpositions. In the end, the outcomes of the Charter may not have beenas significant as the special relationship itself between these nationsthat was fostered by this personal relationship and the Charter. Thisrelationship, despite some moments of diplomatic tension, has endured.26D'Este, 497.9

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Lincoln v. Douglas:The Illinois Senatorial Debates of 1858Kayla (Gaskill) JacobsonandAustin BitterGrand View UniversityOn June 16, 1858, Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) deliveredhis famous “House Divided” Speech in Springfield, Illinois. This cameat the close of the Republican state convention, after which he wasnamed the Republican candidate for the United States Senate. Thoseattending were not aware of the events that would unfold in the monthsfollowing. In this speech, Lincoln said “A house divided against itselfcannot stand,” suggesting that the nation with regard to slavery “willbecome all one thing, or all the other.” 1 This became the focal point ofseven senatorial debates that later took place between Lincoln andDouglas throughout the state of Illinois. The purpose of this paper willbe to examine the conflicting platforms of Abraham Lincoln andSenator Stephen Douglas (1813-1861) on the issues of slavery, itsexpansion, and popular sovereignty. This article will first explore thepolitical atmosphere of the mid-nineteenth century, the careers of thesetwo politicians leading up to the debates, and then proceed to analyzethe Lincoln-Douglas debates held in Illinois during 1858.The issue of slavery permeated the political climate of theUnited States from the very establishment of the nation until the end ofthe Civil War—and arguably even further. 2 It manifested itself as earlyas 1787 with the signing of the Northwest Ordinance, which prohibitedslavery from expanding to the north and the west beyond the OhioRiver. 3 Thus the nation was divided north and south over slavery—andparticularly with regard to its expansion westward—even before ourfirst president took office. This political atmosphere was, in manyways, an extension of the British imperial policies which haddominated North America for many centuries. As imperial theorist andeconomic historian John A. Hobson (1858-1940) later articulated,imperialism embodied “nationalism, internationalism, and colonialism”1Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1832 – 1858, ed. Roy P. Basler(New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1989), 426.2Adam Rothman, Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), xi.3Leonard L. Richards, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War (NewYork: Vintage Books, 2008), 66.10

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)that often led to the subjugation of other people under the falsejustification of actually helping them. 4 Slaves were consideredcommodities to be exploited, traded, bartered, sold, and used. Theywere not considered free individuals but under laws concerningproperty rights. This dehumanization justified slavery in the minds ofmany Americans, just as the subjection of peoples in African and Asiawere justified to the British. Yet, there have also been opponents ofslavery from the beginning of this nation.Tensions between proponents and opponents of slaverybecame more acute with the Louisiana Purchase (1803). Although seenby some as a potential reservation to send Indians from eastern states,American settlement quickly followed the flag across the MississippiRiver. The Louisiana Purchase doubled the land of the United Statesand offered very cheap land opportunities to those who could mobilizethe labor to develop it. Though the actual costs of slavery are higherthan wage earners, slave labor could be moved quickly into the west,especially in areas with profitable cash crops such as cotton. 5 Thiswestward expansion of slavery accelerated the ideological divide andpolitical tension. The expansion of the United States yet again in thewake of the Mexican War (1846-1848) only added fuel to the fire.Organized abolitionist movements became common in the North by the1850s, which led to more and more political confrontations over thefuture of the Union.Compromises had been won between the free and slave statessince the framing of the constitution. By the mid-19 th century, the finalcompromise strategy was popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty leftthe matter of slavery in the hands of the people of each state, ratherthan a decision made by people of the United States as a whole throughtheir representatives. Both methods are democratic, but popularsovereignty placed slavery squarely in the hands of statists rather thannationalists. Yet the issue over what was to be done with territoriesbefore and as they became states was still being debated. 6 In the shortrun, popular sovereignty led to the Free Soil movement (a politicalparty opposed to the expansion of slavery), the expansion of fugitiveslave laws (which called for Northerners to return runaway slaves totheir Southern owners), and the 1850 Compromise (which resulted inthe easing of a deadlock between Northern and Southern states by asomewhat mutually beneficial piece of legislation). 7 The long term4J. A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study, reprint of the 1905 edition (New York: CosimoClassics, 2005), 3, 368. Editor’s note: Adam Smith made a similar conclusion on slaveryin his Wealth of Nations (1776).5Rothman, 70.6Richards, 66.7See William Harris, Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency (Kansas: University Press ofKansas, 2007), 49; and Resolution introduced by Senator Henry Clay in Relation to theAdjustment of all Existing Questions of Controversy between the States arising out of the11

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)result of all of these pieces of legislation was simply a deepeningdivide.In order to better understand where Lincoln and Douglas wereon slavery in 1858, it is helpful to examine their careers prior to thedebates. Even as a young man, many viewed Lincoln as an effectiveand inspirational leader and orator. This was evident when electedcaptain of the local volunteers that fought in the Black Hawk War(1832). Major John Todd Stuart (1807-1885) encouraged Lincoln topursue law and enter into politics. Though self-taught in law andpolitics, Lincoln’s political career began early when he was elected tothe Illinois Assembly in 1834. Two years later, he received his licenseto practice law and was re-elected to the Assembly as the minorityWhig Party floor leader. Lincoln joined the free soil faction of his partyand also supported ending property requirements to vote. 8 Lincoln latersaid of his early positions: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong…I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.” 9 Lincoln waselected to the US House of Representatives in 1846, just in time to voteagainst the Mexican-American War and its further westward expansion.On the national level, Democratic expansionists prevailed against Whigopponents like Lincoln. Also, Lincoln had to face hostility in thesouthern half of his state, let alone nation, with his abolition and antiexpansionrhetoric.Lincoln faced a formidable opponent in Stephen Douglas.Douglas also became interested in law at a young age, and unlikeLincoln, had a formal education in law beginning in 1833, at the age oftwenty. Douglas struggled with both money and recognition until hevolunteered his services to an auctioneer in Illinois. While working as aclerk for the auctioneer, he decided to open a school for clerks in orderto make extra money. In 1834, after about a year, he saved up enoughmoney to finish his formal education in law and was licensed topractice in the state of Illinois. That same year, Douglas was elected asstate’s attorney for the First Judicial Circuit. In 1836, Douglas won aseat in the Illinois Assembly and was appointed to the position ofregistrar of the federal land office in Springfield, Illinois. 10 Two yearsafter that, he ran for the US Congress on a platform opposing corporatecharters for “railroads, canals, insurance companies, hotel companies,steam mill companies &c., &c.” 11 He lost the election by a narrowInstitution of Slavery (“Compromise of 1850”), January 29, 1850; Senate SimpleResolutions, Motions, and Orders of the 31 st Congress, ca. 03/1849-ca. 03/1850; RecordGroup 46, Records of the United States Senate, 1789-1990; National Archives.www.ourdocuments.gov/ doc.php?doc=27&page=transcript (accessed June 7, 2013).8Harris, 9-18.9Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas: the Debates that Defined America (New York:Simon & Schuster, 2008), 32.10Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 3-6.11Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 6.12

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)margin to John Todd Stuart—Lincoln’s mentor. Douglas settled forbeing the state’s secretary of state and took a seat on the IllinoisSupreme Court. In 1843, Douglas finally took his place in the USHouse of Representatives and three years later was a US Senator. 12 Allof this was by the age of 33. This fast-track career earned the shortpolitician the nickname: “Little Giant.”Douglas was passionate about western expansion and thecentrality it offered for Illinois, and especially Chicago, in trade,manufacture, and transportation. While western expansion and thepopular sovereignty compromise of slavery created anxiety for manynorthern politicians, Douglas was unconditional in his desire for theWest to be developed. It soon became apparent that “the realquestion…was not whether Douglas could be trusted to keep Northernhands off slavery in the South but whether he would be willing to givethe South what, in the 1850s, it really wanted, which was a free ticketto legalize slavery in the western territories.” 13 This can be seen inDouglas’ grand idea for expansion in his Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854)that organized the territories of Kansas and Nebraska based upon theidea of popular sovereignty. 14 Douglas defended this platform all theway into his senatorial election debates with Lincoln in 1858. AsDouglas campaigned for re-election in the later part of 1857, Lincolngave speeches of his own against Douglas’ remarks on the Kansas-Nebraska Act and popular sovereignty. By October, Lincoln’sappearances and responses were so close behind Douglas that it had theperception of a debate. This prompted U.S. Senator Norman Judd(1815-1878) to arrange for Lincoln and Douglas to face one another onthe same stand. 15Encouraged by Judd, Lincoln wrote to Douglas on July 24,1858, asking him “to make an arrangement for you and myself todivide time, and address the same audiences during the presentcanvass.” 16 Douglas refused initially, but later agreed with somespecific conditions. They agreed each congressional district in Illinoisshould hear them, so they arranged for seven debates since the districtsthat included Chicago (Second District) and Springfield (Sixth District)were already saturated with their appearances and positions. Douglaschose the cities and the dates of the debates. The first debate took placein Ottawa (Third District) on August 21 th , the second in Freeport (FirstDistrict) on August 27 st , the third in Jonesboro (Ninth District) on12Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 6.13Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 12.14Gerald M. Capers, Stephen A. Douglas: Defender of the Union, ed. Oscar Handlin(Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1959), 93. Editor’s note: The Dred Scott decision(1857) of the US Supreme Court inflamed most northern politicians by nullifying federalprohibition of slavery and prohibiting blacks from becoming legal citizens.15Guelzo Lincoln and Douglas , 35, 90.16Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 91.13

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)September 15 th , the fourth in Charleston (Seventh District) onSeptember 18 th , the fifth in Galesburg (Fourth District) on October 7 th ,the sixth in Quincy (Fifth District) on October 13 th , and the finalappearance in Alton (Eighth District) on October 15 th , 1858. The ruleswere simple: The first speaker had an hour, followed by a responsefrom the other that lasted for an hour and a half, concluding with arebuttal by the first man lasting a half-hour. 17 Unlike other politicaldebates, the debates between Lincoln and Douglas did not focus oneconomics, trade, or other commonly debated topics. Rather, thedebates between these men focused on expansion of slavery in theWest. 18Ottawa was an interesting first venue as a predominatelyRepublican city. 19 Douglas took to the podium first with his speechthat was allotted to last for an hour. In his opening statement, Douglasaddressed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he had helped pass throughCongress with the compromise of popular sovereignty—the standardstates’ rights defense: “It is the true intent and meaning of this act notto legislate slavery into any State or Territory, or to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulatetheir domestic institutions in their own way, subject only to federalconstitution.” 20 Douglas continued by directing a statement towardLincoln himself involving his stance on the admission of a new state:“I desire him to answer whether he stands pledged to-day, as he did in1854, against the admission of any more slave States into the Union,even if the people want them.” 21 With this accusatory statement,Douglas attempted to make it obvious to the audience that Lincolnwould do what he wanted regardless of the desires of his constituents.He proceeded by stating that he wondered if Lincoln stood to prohibitslavery in all territory of the United States, something that manyindividuals opposed. In referencing Lincoln’s now famous “HouseDivided” speech, Douglas questioned “Why can it not exist dividedinto free and slave States? Washington, Jefferson…and the [other]great men of that day, made this Government divided into free Statesand slave States.” Douglas used the Founders to argue: “I believe it[this government] was made by white men, for the benefit of white menand their posterity forever.” 22When Douglas concluded his hour long speech, it was up toLincoln to defend himself against such critical remarks by “Judge17Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 92.18David Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas and Slavery (Chicago: The University of ChicagoPress, 1990), 52.19Zarefsky, 55.20Lincoln, 496-497.21Lincoln, 499.22Lincoln, 503-504.14

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Douglas”—Lincoln’s own playful nickname for the Senator. 23 Heoffered the olive branch: “I will say here, while upon this subject, thatI have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institutionof slavery in the States where it exists.” But he also challenged hisaudience (and the US Supreme Court’s decision of the prior year) thatthere was no reason why blacks were not entitled to the same rightsstated in the Declaration of Independence. 24 It seemed Lincoln avoideda nationalist response to Douglas’ states’ rights position, by provokinga libertarian ideal. Concluding with more than fifteen minutesremaining of his allowed time, Lincoln seemed nervous anddefensive. 25 His definition of popular sovereignty was a very key pointin his speech. He stated that popular sovereignty “does allow thepeople of a Territory to have Slavery it they want to, but does not allowthem not to have it if they do not want it.” The way he phrased thiscaused many laughs and applause to erupt throughout the crowd ofspectators. 26With constant interruptions from the audience and Lincolnhimself, Douglas used his half hour rebuttal to further accuse Lincolnof avoiding the questions posed to him in his first statement: “I askedhim to answer me and you whether he would vote to admit a State intothe Union, with slavery or without it, as its own people might choose.He did not answer that question. He dodges that question.” 27 Douglascontinued, throughout the remainder of his speech, to point out toaudience members Lincoln’s inability to answer the simple questionshe posed for him. The Illinois State Register, a paper that favored theDemocratic candidate, cast Lincoln as having “stumbled, floundered,and, instead of the speech that he had prepared to make, bored hisaudience by using up a large portion of his time reading from a speechof 1854, of his own.” The Chicago Times had such headlines as“Lincoln’s Heart Fails Him! Lincoln’s Legs Fail Him! Lincoln’sTongue Fails Him!” 28 While it may have seemed like Douglas had themomentum coming out of the first debate in Ottawa, Democratic paperswere at fault for providing such biased remarks while other papers hadmixed reviews. Papers such as the Alton Weekly Courier and theWeekly North-Western Gazette had different perspectives. The former:“The Republicans of Ottawa are in high glee. The triumphant mannerin which Lincoln handled Douglas this afternoon has filled them withspirit and confidence…the Little Giant is doomed.” 29 The Weekly23Lincoln, 508.24Lincoln, 512.25Zarefsky, 55.26Lincoln, 515.27Lincoln, 530.28Zarefsky, 55.29See George T. Brown, “The Great Debate between Lincoln and Douglas,” AltonWeekly Courier, August 26, 1858, Alton, Illinois, in the Northern Illinois University15

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)North-Western Gazette: “We think Mr. Lincoln has decidedly theadvantage. Not only are his doctrines truer and better…but he statesthem with more propriety, and with an infinitely better temper.” 30 Thefirst round seemed inconclusive.Just a few days later, Douglas and Lincoln debated inFreeport—another Republican stronghold. 31 This time, Lincoln wasthe first to address the audience, and he used this to his advantage.Douglas had issued a series of questions in the Chicago Times, towhich Lincoln responded in concise responses that agitated Douglas,who continued to be frustrated with Lincoln’s refusal to be corned intohard positions. Regarding the fugitive slave law, Lincoln stated that hedid not favor a repeal of the law. Lincoln even stated that he did notstand against the admission of slave States into the Union.Furthermore, when questioned about the admission of a new state intothe Union, Lincoln agreed that the people of the state had the right to astate constitution that they saw as fit for them. When asked if he wouldabolish slavery in the District of Columbia, Lincoln once again statedthat he did not “stand to-day pledged to the abolition of slavery in theDistrict of Columbia.” Lincoln seemed to escape Douglas’ trap onstates’ rights and even the federal district under Congressionaljurisdiction. But over the new settlement to the West: “I am impliedly,if not expressly, pledged to a belief in the right and duty of Congress toprohibit slavery in all the United States Territories.” Lincoln seemed toposition himself as a senator that would fight the good fight inWashington by allowing the acquisition of new territory, even if it“would or would not aggravate the slavery question amongourselves.” 32Then, Lincoln did the questioning. Lincoln targetedcontroversial Kansas: “If the people of Kansas shall…adopt a StateConstitution, and ask admission into the Union under it, before theyhave the requisite number of inhabitants…will you vote to admitthem?” In the second question, which proved to be quite complicatedfor Douglas, Lincoln asked was whether “the people of the UnitedStates Territory… [can] exclude slavery from its limits prior to theformation of a State Constitution?” The third question, dealing withthe Judiciary branch of the United States government, was on whetherDouglas would follow the decisions made by the Supreme Court if itsmembers decided that states cannot exclude slavery from their limitsLibraries Digitization Projects, for coverage of the Ottawa debate on August 21 st .lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgibin/philologic/ getobject.pl?c.2271:1.lincoln (accessed June 3,2013).30H. H. Houghton, “Lincoln and Douglas,” Weekly North-Western Gazette, September 7,1858, Galena, Illinois, in the NIU Libraries Digitization Projects. lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgibin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.2581:1.lincoln(accessed June 3, 2013).31Zarefsky, 56.32Lincoln, 538-539.16

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)And finally, Lincoln requested to know if Douglas was in favor ofacquiring new territory even if it would affect the slavery question ofthe nation? 33 While Lincoln labored around the questions of Douglas,Douglas went straight to the point. He would not make Kansas anexception to the rule. He would not vote to admit Kansas into theUnion until the correct population was reached:I made that proposition in the Senate in 1856…in a bill providingthat no territory of the United States should…apply for admissionuntil it had the requisite population. On another occasion I proposedthat neither Kansas, or any other territory, should be admitteduntil it had the requisite population. 34Lincoln may have lured Douglas into overplaying his popularsovereignty strategy, as Douglas responded: “[I]n my opinion thepeople of a territory can, by lawful means, exclude slavery from theirlimits prior to the formation of a State Constitution.” 35 This alarmedSouthern Democrats. Douglas seemed confused by Lincoln’s thirdquestion and merely stated that it would be nearly impossible for thatsituation to occur since the Supreme Court would to follow theConstitution. Finally, Douglas said that he was in favor of acquiringnew territory as long as the people who inhabit that territory are free tochoose if they will admit slavery in their state or not. 36 Upon returningto the stage to conclude the debate, Lincoln was greeted with manycheers from audience members. Lincoln used his half hour rebuttal totell the listeners that he believed he answered the questions posed forhim at the Ottawa debate clearly and precisely. He continued byarguing the point he made in the “House Divided” speech—that theUnion cannot survive half slave and half free. 37 There were againmixed reviews. Democratic papers amused themselves over theFreeport debate with cynical remarks about Lincoln: “The LionFrightens the ‘Dog’!” and “Lincoln Routed! He can’t Find the Spot!” 38Republican papers, like the Weekly North-Western Gazette, made theirown headlines “Lincoln Defnines His Position” and “The Little GiantCornered” with their analysis: “Yesterday was a great day in our State,as it witnessed the full and complete triumph of our noble champion33Lincoln, 542. Editor’s note: President Franklin Pierce refused to recognize the FreeSoil government in Topeka in 1856, the same year that pro-slavery elements fromMissouri also burned the Free Soil stronghold of Lawrence as well as the physical attackon Free Soil Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber by pro-slavery congressmen.34Lincoln, 550.35Lincoln, 551.36Lincoln, 554-555.37Lincoln, 573, 576.38Zarefsky, 57.17

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)over Senator Douglas.” 39 The Quincy Daily Whig and Republicanstated: “Mr. Douglas, at every step, becomes more and more entangledin inconsistencies and contradictions. The ‘Russian Bear’ has beencaught in the net of his own weaving.” 40The third debate, on September 15 th , brought the two men toJonesboro, a town in the middle of a Democratic territory and astronghold for President James Buchanan (1791-1868). This district,located near the southernmost tip of the state, held the greatest aversionto the black population. 41 Taking to the stage first, Douglas opened hisspeech by referencing the Compromise of 1850, in which it was statedthat the people of the State should be allowed to regulate their owninstitutions subjected to no other limitation other than that in theConstitution. During the period in which the compromise was created,there was great unity between the Democratic Party and Whig Party—who Douglas claimed were united to the principles established in theCompromise of 1850. Douglas then claimed that the Whig Party hadbeen turned into a sectional party, due in part to Lincoln and otherRepublicans trying to eliminate the Whig Party all together. In aneffort to draw in former Whigs, Douglas remarked: “All Union-lovingmen, whether Whigs, Democrats…ought to rally under the stars andstripes in defense of the Constitution, as our fathers made it, and of theUnion as it has existed under the Constitution.” 42 Douglas once againused his popular sovereignty argument as a defense of democracy bystating that Lincoln would not allow new states that wanted to be slave.He continued by saying that Lincoln and his followers want the fugitiveslave law to be repealed, slavery in the District of Columbia to beabolished, and the end of the slave trade between different States of theUnion. 43 Then, Douglas took a step back and addressed Lincoln’s“House Divided” speech, and replied, “Why can it not last if we willexecute the government in the same spirit and upon the same principlesupon which it is founded.” 44 In his next point, Douglas decided todiscuss the Dred Scott ruling of the prior year. Douglas accusedLincoln of opposing the decision because it denied blacks the rights ofcitizenship—something that Lincoln appeared to be advocating.39H. H. Houghton, “The Great Debate at Freeport,” Weekly North-Western Gazette,September 7, 1858, Galena, Illinois, in the NIU Libraries Digitization Projects.lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.2612:1.lincoln (accessed June 7,2013).40John T. Morton, “Lincoln and Douglas at Freeport,” Quincy Daily Whig andRepublican, September 1, 1858, Quincy, Illinois, in the NIU Libraries DigitizationProjects . lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.2517:1.lincoln (accessedJune 7, 2013).41Zarefsky, 583.42Lincoln, 587-588.43Lincoln, 589.44Lincoln, 596.18

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Douglas mimicked the majority decision: “I hold that a Negro is notand never ought to be a citizen of the United States.” He once againreiterated his belief that the government was made for the benefit of thewhite people. 45 Douglas went further than white supremacy to outrightimperial vision in his final point. He noted that if the Union adhered tothe principles established in the Compromise of 1850, the Union wouldexpand and extend until it covered the whole continent. Making Cubaa point of interest, and later Mexico and Canada, Douglas statedarrogantly: “When we get Cuba we must take it as we find it, leavingthe people to decide the question of slavery for themselves.” 46When Lincoln took the stand for his hour and a half responseto Douglas’s opening statements, he once again gave his reasons whyhe does not believe the Union could survive if it were to be split in two:I say when this government was first established it was thepolicy of its founders to prohibit the spread of slavery into thenew Territories of the United States, where it had not existed.But Judge Douglas and his friends have broken up that policyand placed it upon a new basis by which it is to becomenational and perpetual. 47Then turning to address the issue of the compromise negotiated byHenry Clay (1777-1850) in 1850, Lincoln pointed out how Douglasthought it was his duty to organize the territory above the lineestablished as the border between slave and free. Lincoln argued thatthe Compromise of 1850 did not break the Missouri Compromise(1820), but when Douglas decided to step over that boundary andorganize the Kansas-Nebraska territory, he broke the MissouriCompromise. 48 In Jonesboro, Lincoln accused Douglas of notanswering the questions that were directed towards him in Freeport.With regard to backing a Free Soil Kansas, Lincoln told the audiencethat Douglas never gave a “yes or no – I will or I won’t.” WhenDouglas responded to Lincoln’s second question at Freeport on whethera territory could exclude slavery before it was a state, Douglassuggested that there were ways that Congress could influence thisbefore a state constitution was written by “withholding…indispensableassistance to it in the way of legislation” or “by unfriendly legislation.”Lincoln was quick to point out that the Supreme Court, in the DredScott decision (1857), had just made unconstitutional such federal45Lincoln, 598.46Lincoln, 600-601. Editor’s note: While Spain abolished slavery in most of its coloniesin 1811, slavery existed in Cuba until 1886.47Lincoln, 603.48Lincoln, 606. Editor’s note: There was general debate over whether the MissouriCompromise line (Missouri’s southern border) extended across the new territories to theWest, dividing slave and free.19

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)interference. 49 Now Douglas was cornered by the Constitution asinterpreted by the current Supreme Court. Then Lincoln skipped pastpopular sovereignty arguments and humanized the issue by a directconfrontation over property rights: “If the slaveholding citizens of aUnited States Territory should need and demand Congressionallegislation for the protection of their slave property in such territory,would you, as a member of Congress, vote for or against suchlegislation?” This question posed political liabilities for Douglasconflict. A negative answer would infuriate his Southern Democraticallies and positive answer might alienate any Free-Soilers or formerWhigs that he was attempting to woo.” 50 Douglas approached the standand simply rang-out his party’s platform: “It is a fundamental article inthe Democratic creed that there should be non-interference and noninterventionby Congress with slavery in the States or territories.” 51This, of course, was already in dispute with his earlier answer thatCongress could intervene. After the third debate at Jonesboro,newspapers again offered mixed, partisan reviews flooded the paperswith such comments as “Poor Lincoln was greatly embarrassed,” or“Mr. Douglas rehearsed his stereotyped harangue already deliveredwhenever he has made a political speech; while Mr. Lincoln cameforward with a number of new points.” 52Three days later, Lincoln and Douglas met in Charleston, adistrict whose population predominately favored the old Whig Party. Inthe previous three debates the opening speaker touched on manydifferent points, which allowed the following speaker an opportunity toanswer them. However, after reassuring audience members that he wasnot in favor of racial equality, Lincoln turned the main topic of hisspeech into charging Douglas with conspiracy in depriving Kansas ofthe opportunity to vote on whether their state would be free or slave. 53This greatly angered Douglas. When he approached the stand to givehis response to Lincoln’s opening remarks, he pointed out that “the ruleof such discussion is, that the opening speaker shall touch upon all thepoints he intends to discuss in order that his opponent, in reply, shallhave the opportunity of answering them.” 54 In keeping with the newtheme that seemed to have emerged at that debate, Douglas used theremainder of his hour and a half long response to charge Lincoln andLyman Trumbull (1813-1896), the current senior United States Senatorof Illinois, of conspiring to “abolitionize the old political parties.” 5549Lincoln, 616-617.50Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 178.51Lincoln, 632.52Zarefsky, 59.53Zarefsky, 60.54Lincoln, 651.55Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 203.20

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Douglas once again went on to accuse Lincoln of favoring racialequality, which Lincoln denied. He used this opportunity to state hisstance on racial equality saying: “I say to you in all frankness,gentlemen, that in my opinion a Negro is not a citizen, cannot be, andought not to be, under the constitution of the United States.” 56 InLincoln’s rebuttal, he used his time to deny the accusations madeagainst him by Douglas. Lincoln responded to the allegation that heconspired with Trumbull to rid the old parties with: “I have twice toldJudge Douglas to his face that from beginning to end there is not oneword of truth in it.” 57 He further denied his favoritism towards racialequality and offered a correction that he did not vote against troopsupplies for the Mexican War—which Douglas had accused him of inhis speech. 58 Like the previous three debates, assessments differedgreatly among newspapers in the area. The Weekly North-WesternGazette noted that “Douglas has changed front so often that the peoplecannot place any reliance upon him.” 59 A similar reaction came fromthe Prairie Beacon News, which noted in their paper: “At theconclusion of the rejoinder, the applause was so great that there was nomistaking the fact that an overwhelming majority of that large audiencewere for Lincoln.” 60Less than a month later, the fifth debate took place inGalesburg, a Republican stronghold, in front of approximately fifteento twenty thousand individuals, which was the largest crowd yet. 61 Inhis opening statement, Douglas used the beginning of his time to againannounce that the Republican Party was a sectional party. “But nowyou have a sectional organization, a party which appeals to the northernsection of the Union…[in the] hope that they will be able to unite thenorthern States in one great sectional party.” 62 Once again, Douglasannounced that Lincoln, and the Republican Party, were for racialequality, and that Lincoln had said one thing in the northern part of thestate and another in the southern part: “[I]n one part of the State hestood up for negro equality, and in another part for political effect,56Lincoln, 673.57Lincoln, 678. Editor’s note: Since the Democratic and former Whig parties both hadNorthern and Southern factions, Douglas’ accusation is that Lincoln’s Republican party isattempting to destroy their opponents by using slavery as a sectional issue merely to winthe election.58Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 203.59H. H. Houghton, “The Charleston Debate,” Weekly North-Western Gazette ,September28, 1858, Galena, Illinois, in NIU Libraries Digitization Projects, lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgibin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.2592:1.lincoln(accessed June 7, 2013).60John T. Morton, “Lincoln and Douglas at Charleston,” Quincy Daily Whig andRepublican, September 23, 1858, Quincy, Illinois, in NIU Libraries DigitizationProjects, lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.2513:1.lincoln (accessedJune 7, 2013).61Zarefsky, 62.62Lincoln, 693.21

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)sovereignty or states’ right strategy: “This government was made uponthe great basis of the sovereignty of the States, the right of each State toregulate its own domestic institutions to suit itself.” 73 He criticizedLincoln for misunderstanding the intentions of the Founders. 74 Healleged: “For this reason this Union was established on the right ofeach State to do as it pleased on the question of slavery.” 75 Lincolnattacked popular sovereignty in his final argument. He believed that itstates’ rights over the slavery issue threatened the Union. He alsonoted that “popular sovereignty grants slaveholders an advantage insettling the territories.” He concluded by reiterating his belief that theruling in Dred Scott was contradictory to popular sovereignty. Lincolnseemed to paint the picture of eventual conflict in the “house divided.”Douglas, on the other hand, simply repeated the claim in his finalrebuttal that “the Founders adopted popular sovereignty as the means ofdealing with slavery.” Douglas painted a different picture of the futurethat “popular sovereignty is the only guarantee of peace.” 76 Althoughno clear winner emerged from the final debate, the Chicago Timesnoted that “this last effort of Mr. Lincoln’s is the lamest and mostimpotent attempt he has yet made.” Conversely, the Illinois StateJournal state: “All accounts agree that Mr. Douglas was badly whippedout…Lincoln’s sledgehammer arguments have been entirely too muchfor him.” 77 On January 5, 1859, Stephen Douglas was reelected by avote of 54-46 along mainly north-south lines in the state.Although the debates have been widely scrutinized byhistorians for importance, Albert J. Beveridge (1862-1927) noted in hisfamous but posthumous 1928 biography of Lincoln that based “solelyon their merits, the debates themselves deserve little notice. For themost part each speaker merely repeats what he had said before.” 78 Yet,as a historical marker, the Lincoln-Douglas debates carried an on-goingargument to a perceived threshold in public discourse. These debatesalso serve as a historical marker offering insights into Lincoln’sdevelopment over the issue of slavery. Had Lincoln lost the presidentialelection a year later to Douglas in 1860, the debates may not beremembered. Since Lincoln lost the US Senate seat but later won theUS Presidency, these debates are worthy of investigation. The opinions73Lincoln, 776.74Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 269.75Lincoln, 777. Editor’s note: The Founders agreed not to debate the issue of slavery fortwenty years, which was more of a delaying tactic than a definitive claim as Douglassuggests. Upon leaving Philadelphia at the end of the Constitutional Convention, GeorgeWashington was asked how long the Union would last, to which he responded: Twentyyears.76Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas , 269.77Zarefsky, 66.78Allen C. Guelzo, "Houses Divided: Lincoln, Douglas, and the Political Landscape of1858," Journal of American History 94, no. 2 (2007): 393.23

Lincoln v. Douglas <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)and statements made by Lincoln during these debates show us histendency towards abolition, but hesitancy to break with the status quoof the era. Lincoln revealed that he believed all men to have the right to“life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” that slavery was immoral(at least in legal terms), that the expansion of slavery into the Westshould be stopped, and that the issue of slavery could be decided as anation by Congress. 79 In the end, Douglas won a state race with a statistplatform, while Lincoln would win a national race with a nationalplatform.79Roy Morris, Jr., The Long Pursuit (New York, Harper Collins Publishers, 2008), 109,114.24

The Treaty of London (1838) <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)The Treaty of London (1838):Its Reinterpretation and Impact on the Outbreak andConclusion of the First World War†Micheal CollinsGrand View UniversityFrederick the Great (1712-1786) once said: “All guaranteesare like a watermark, more to satisfy the eyes than utility.” 1 This mightcertainly be the case with guarantees based upon jus gentium, or the“law of nations,” which is a concept left over from the height of theRoman Republic. Jus gentium is a legal and political framework, or aset of expectations and norms, common for all. 2 This ideal isfoundational for European diplomacy with regard to generalexpectations of behavior while respecting differing sovereign law codesof individual nations. The London Treaty of 1839 provides an excellentexample of jus gentium and its complications in diplomacy. In 1914,Great Britain used the treaty as justification in coming to the defense ofBelgium’s neutrality by declaring war on Germany. Just as theGermans invaded, British scholars and legal authorities quickly camewith books and articles on the Treaty of 1839 and its application byeither reinterpreting or redefining its words and utility. One inparticular stands out: England’s Guarantee to Belgium andLuxembourg, written by scholars Charles Sanger (1871-1930) andHenry Norton (1886-1937) in 1915. 3 Like many other publications ofthe period, this book looked at the core of the Treaty of 1839 focusingon the meaning of two words: “guarantee” and “neutrality.” Exploringfurther than other publications, these authors also reviewedinterpretations of the intent and meaning behind those same words asunderstood in every crisis in Europe involving pre-1914 Belgium.Sanger and Norton concluded that the force of the words and status ofBelgian neutrality were being interpreted by the British governmentcorrectly in 1914, thus legitimizing its declaration of war on Germany.Yet, there is sufficient evidence to the contrary. There was no clear†This paper was presented at the 56 th Missouri Valley History Conference, March 2013,Omaha, Nebraska.1Charles Sanger and Henry Norton, England’s Guarantee to Belgium and Luxembourg,with the Full Text of Treaties (New York, Scribner’s and Sons, 1915), Title Page.2Gordon E. Sherman, "Jus Gentium and International Law," American Journal ofInternational Law 12, No. 1 (1918): 57.3Sanger and Norton, 25-48, 77, and 93-113.25

The Treaty of London (1838) <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)consensus between the original signatory powers of 1839 that offereduniversally accepted interpretations that “guaranteed” Belgianneutrality in the 1914 context. In fact, it was widely known that in1887, British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury (Robert Gascoyne-Cecil,1830-1903) “had been prepared to sacrifice” the 1839 treaty. 4Considerable shifts of the meaning of “neutrality” and “guarantee” hadtaken place between signatory powers like France, Britain andGermany. At every major crisis that directly threatened Belgian“neutrality” between 1839 and 1914, reinterpretations of “guarantee”and “neutrality” were made and remade. This paper argues that Belgianneutrality as guaranteed under the 1839 treaty may no longer have beenunderstood the same way by any of the signatory powers in 1914,including Great Britain. Yet, the 1839 treaty was dusted off and usedfor a declaration of war and at the Treaty of Versailles in thepunishment of Germany. It should be noted that this paper does notdefend German aggression nor will it seek legitimacy for the Germaninvasion of Belgium, but it merely questions the manner in which the1839 treaty was used against Germany.Treaties are often viewed as “expression[s] of conditions andrelationships of power in existence at the time of their making” and yet,“they cannot hope to freeze forever the status quo of any particularmoment of time.” 5 The Treaty of 1839 is no different, so in order tounderstand the impact of the burden of responsibility that the Treaty of1839 placed on the signatory powers, a concise historical backgroundof its origins is necessary. Knowing the circumstances that led to thecreation of this treaty helps us to understand its misapplication in 1914.We need to know the intent behind Article I of the Treaty of 1839 thatheld the “guarantee of their said majesties,” as well as Belgium’s“independent and perpetually neutral state” as established within theannex portion of Article VII. 6The origins of the Treaties of London 1839 can be traced backto the end of the Napoleonic wars (1803-1815) with the Congress ofVienna. 7 In 1815, Holland and Belgium were combined into onenation. 8 Continual strife led to a Belgian revolt on August 25 th 1830. 94Max Montgelas, “The Case for the Central Powers Article 16,” The Outbreak of WorldWar I: Who Was Responsible? Dwight Lee, ed. (New York, Random House, 1977), 7-8.5Rene Albrecht-Carrie, A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna(New York: Harper & Row, 1973), 7.6Treaty of London 1839, Article I, quoted in Sanger and Norton, 126.7The Napoleonic wars were a series of wars and or other conflicts that was primarilyfought on the European continent and on the high seas, involving such belligerents asFrance, Britain, Russia and Prussia.8The Congress of Vienna was convened to deal with the aftermath of the Frenchrevolution and the Napoleonic wars which resulted in a drastic restructuring of Europe.9Sanger and Nelson, 7-8. The irony is that the Belgium revolt happened because of theFrench revolt, and the timing also affected the Polish revolution.26

The Treaty of London (1838) <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)Because of the failure of King William I (1772-1843) of theNetherlands to successfully end the revolt coupled with other pressureson him, King William turned to the prevalent powers of the time,asking them for help in resolving this conflict. He could do this becausethe powers were “obligated to come to [his] assistance” as the result ofstipulations from the Congress of Vienna. 10 Although tensions existedbetween Britain and France, the likelihood that war would recommencebecause of another revolt in the Lowlands was not there, due to a“Europe, sickened with war”. 11 By January of 1831, certain protocolswere established in setting the ground work for creating the nation ofBelgium. 12 The interested parties involved in the creation of thetreaties included, Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria and later France. 13Various agreements and annexes would become the body of the Treatyof 1839. Thus the treaty’s first utility was to serve as a peacefuldissolution of the union between Holland and Belgium while providingthe foundation to a process that would eventually define Belgium’sborders. 14 The larger picture, often missed, is that the treaty preventedanother continental war that none of the current powers wanted.Within this context, let us look at the word “guarantee” as itwas interpreted in the Treaty of London 1839. The intent behind themeaning of the word “guarantee” was to bind those who signed thetreaty in a collective guarantee. 15 The real power of the treaty lay inthis collective guarantee. Should one of the signatory powers, such asFrance, decide to invade Belgium, the others would be obligated tointervene on Belgium’s behalf. Yet, this is where the conundrumemerges. There was no word or explanation that the agreement wascollective in nature. The word collective was never used, and it wasassumed in the spirit but not the letter of the treaty. Multipleinterpretations emerged about how a signatory should act if and whenthey were called upon to fulfill the “guarantee” which created by thetreaty.10William L. Langer, Political and Social Upheaval: 1832-1852 (New York: Harper &Row, 1969), 283. King William was the ruler of the Netherlands at the time of theBelgium Revolt. The prevalent powers of the time were Austria, Britain, Russia and theGerman Confederation. Editor’s note: He should not be confused with William ofOrange-Nassau (1650-1702).11L. G. Redmond-Howard, Belgium and the Belgian People (London: Simpkin,Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Company, 1914), 31.12Albrecht-Carrie, 34.13France may have participated much sooner had they not been dealing with their ownrevolts or if the king had not issued the assurance that France did not have any interest inBelgium at that time.14See Sanger and Norton, 126, for Article III of the Treaty of London 1839; and 127, forAnnex Article I.15Frederick E. Smith (Earl of Birkenhead) and James Wylie, “Treaty of London 1839,”in International Law, 4 th edition (Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1911).27

The Treaty of London (1838) <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)This state of neutrality was nothing new to the powers ofEurope in 1839. In many ways it acted as a buffer to keep both statesand citizens out of the line of fire. Belgium took the stance ofneutrality and sought freedom from the threat of military influence. Thetreaty did not bar Belgium from building a military or constructinggarrison forts. However, there was one main exception to that ability.Article XIV of the treaty stipulated that the port of Antwerp shallremain “solely a port of commerce,” and, by extending the concept ofneutrality further, Antwerp could not be a port of call for any militaryforces, including those of Belgium itself. Belgium is thus “bound toobserve such neutrality towards all other states,” the same as any othersignatory of the treaty. 16In the decades that followed 1839, there was one crisis afteranother, coupled with armed conflicts that spread across Europe andhad an impact on the balance of power in Europe. This was especiallytrue about the Luxembourg Crisis of 1867. The Prussian ChancellorOtto von Bismarck (1815-1898), with both diplomatic and militarymeans at his disposal, was fresh from military victories over Denmark(1864) and Austria (1866). When French Emperor Louis Napoleon III(1808-1873) offered to purchase Luxembourg from the King of theNetherlands with the hope of incorporating it into France, it was withNapoleon III’s expectation that Prussia would allow it as“compensation” for “France’s neutrality during the Austro-Prussianconflict.” 17 Bismarck’s response “made it perfectly plain that Francecould not have an inch of German territory nor aid in acquiringBelgium and Luxembourg.” 18 In an attempt to avert another war thatcould encompass all of Europe, the other powers stepped-in with theTreaty of London in1867.The Treaty of London 1867 was believed at the time to releasethe tension between France and Prussia. The status quo of the GrandDuchy of Luxembourg had changed with the “dissolution of the ties bywhich it was attached to the late Germanic Confederation.” 19 Afteraffirming this dissolution, Luxembourg became an independent statealong the lines as Belgium, but with some rather significant changes.Perhaps the biggest change was that Luxembourg was only allowed tohave enough troops to maintain domestic order, no more, no less. This16See Sanger and Norton, 135, for Annex Article XIV of the Treaty of London , 1839,and 130 for Annex Article VII.17Harold Talbot Parker, and Marvin Luther Brown, Major Themes in Modern EuropeanHistory: An Invitation to Inquiry and Reflection (Durham, N.C.: Moore Publishing,1974), 572.18Parker and Brown, 573. Editor’s note: Luxembourg was part of the Prussian customsunion and was seen by many to be in Prussia’s sphere of influence. It had also beenattached to German states during the period of Napoleon Bonaparte’s GermanConfederation., 1806-1813).19See Sanger and Norton, 145, for Treaty of London, 1867, Article VI.28

The Treaty of London (1838) <strong>MUNINN</strong> Volume 2 (2013)demilitarization with neutrality was similar to the 1839 treaty regardingAntwerp being demilitarized. The difference was that Belgium couldstill determine the size of its own army. Furthermore, in Article V ofthe 1867 Treaty, Luxembourg agreed not to build fortifications or haveany military establishment. 20The 1867 treaty contained the same two key words from the1839 treaty, “guarantee” and “neutrality.” But there is a key differenceas Article II of the 1867 Treaty has a “collective guarantee.” 21Ironically, the collective part of the guarantee was important toBismarck’s understanding of neutrality, while British Prime MinisterLord Derby (Edward Smith-Stanley, 1799-1869) took an oppositestance that the 1839 treaty was a collective guarantee, while the 1867treaty was a singular guarantee—ignoring the specific language of thearticles. As for the word “neutrality,” this 1867 treaty would bearwitness to changes in Europe that were taking place. For Luxembourgthe meaning behind the word neutral took on a different intent than thatof Belgium’s 1839 neutrality guarantee. The intent was that ifLuxembourg wished to remain neutral, other states were obligated toprotect them in conjunction with one another.Though the tension abated between France and Prussia for ashort period, war between the two states seemed inevitable. When theFranco-Prussian War (1870-1871) erupted, it demonstrated that Britishconfidence in the treaty of 1839 was starting to buckle. There wasfierce debate in the British Parliament on how to keep Belgium frombeing invaded. From the British point of view, the word “guarantee”meant entirely different things depending on the viewpoints of thosewho were in power at a given point in time. Even the form and type ofneutrality was brought into question and there were cases in whichthere were at least two opposing viewpoints of what a neutral nationcould and should do. So, the British feared that it was only a matter oftime before Belgium’s neutrality would be violated either by Prussia orFrance. The British devised a way to reinforce the treaty of 1839 bydrawing up a new treaty. The intention can be surmised in Article IIthat whoever should violate Belgium’s neutrality, Britain will comeinto the conflict to ensure that Belgium independence is protected.Unlike other agreements of neutrality, this treaty had a time limitimposed on it, which was only in effect as long as the conflict“continued and for twelve months after the ratification of any Treaty ofPeace concluded between those Parties.” 22After the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), Belgium becameone of the most prosperous countries in Europe. Some would go as far20Sanger and Norton, 144.21Sanger and Norton, 143.22See Sanger and Norton, 147 and 150, for the Treaty of London, 1870, 147. There aretwo separate and distinct treaties for both Prussia, and France.29