NEWHORIZON

NEWHORIZON - Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance

NEWHORIZON - Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>NEWHORIZON</strong> April to June 2013<br />

POINT OF VIEW<br />

various ‘cleansing’ or ‘purification’<br />

mechanisms that are operative<br />

upon and after the occurrence<br />

of the equity investment and are<br />

designed to address subsequent<br />

impure consequences (e.g., interest<br />

income, which is cleansed through<br />

donation to charity).<br />

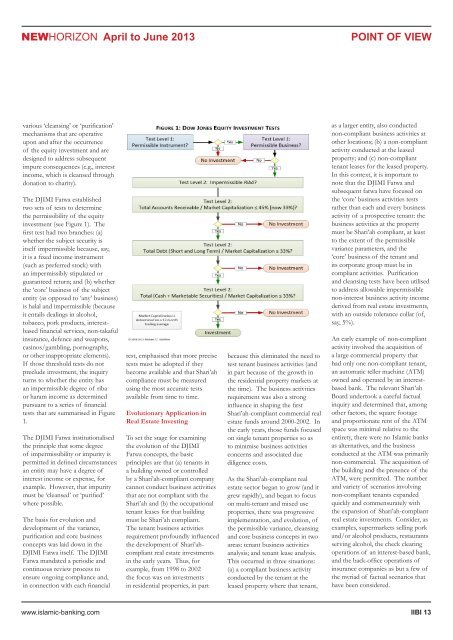

The DJIMI Fatwa established<br />

two sets of tests to determine<br />

the permissibility of the equity<br />

investment (see Figure 1). The<br />

first test had two branches: (a)<br />

whether the subject security is<br />

itself impermissible because, say,<br />

it is a fixed income instrument<br />

(such as preferred stock) with<br />

an impermissibly stipulated or<br />

guaranteed return; and (b) whether<br />

the ‘core’ business of the subject<br />

entity (as opposed to ‘any’ business)<br />

is halal and impermissible (because<br />

it entails dealings in alcohol,<br />

tobacco, pork products, interestbased<br />

financial services, non-takaful<br />

insurance, defence and weapons,<br />

casinos/gambling, pornography,<br />

or other inappropriate elements).<br />

If those threshold tests do not<br />

preclude investment, the inquiry<br />

turns to whether the entity has<br />

an impermissible degree of riba<br />

or haram income as determined<br />

pursuant to a series of financial<br />

tests that are summarised in Figure<br />

1.<br />

The DJIMI Fatwa institutionalised<br />

the principle that some degree<br />

of impermissibility or impurity is<br />

permitted in defined circumstances:<br />

an entity may have a degree of<br />

interest income or expense, for<br />

example. However, that impurity<br />

must be ‘cleansed’ or ‘purified’<br />

where possible.<br />

The basis for evolution and<br />

development of the variance,<br />

purification and core business<br />

concepts was laid down in the<br />

DJIMI Fatwa itself. The DJIMI<br />

Fatwa mandated a periodic and<br />

continuous review process to<br />

ensure ongoing compliance and,<br />

in connection with each financial<br />

test, emphasised that more precise<br />

tests must be adopted if they<br />

become available and that Shari’ah<br />

compliance must be measured<br />

using the most accurate tests<br />

available from time to time.<br />

Evolutionary Application in<br />

Real Estate Investing<br />

To set the stage for examining<br />

the evolution of the DJIMI<br />

Fatwa concepts, the basic<br />

principles are that (a) tenants in<br />

a building owned or controlled<br />

by a Shari’ah-compliant company<br />

cannot conduct business activities<br />

that are not compliant with the<br />

Shari’ah and (b) the occupational<br />

tenant leases for that building<br />

must be Shari’ah compliant.<br />

The tenant business activities<br />

requirement profoundly influenced<br />

the development of Shari’ahcompliant<br />

real estate investments<br />

in the early years. Thus, for<br />

example, from 1998 to 2002<br />

the focus was on investments<br />

in residential properties, in part<br />

because this eliminated the need to<br />

test tenant business activities (and<br />

in part because of the growth in<br />

the residential property markets at<br />

the time). The business activities<br />

requirement was also a strong<br />

influence in shaping the first<br />

Shari’ah-compliant commercial real<br />

estate funds around 2000-2002. In<br />

the early years, those funds focused<br />

on single tenant properties so as<br />

to minimise business activities<br />

concerns and associated due<br />

diligence costs.<br />

As the Shari’ah-compliant real<br />

estate sector began to grow (and it<br />

grew rapidly), and began to focus<br />

on multi-tenant and mixed use<br />

properties, there was progressive<br />

implementation, and evolution, of<br />

the permissible variance, cleansing<br />

and core business concepts in two<br />

areas: tenant business activities<br />

analysis; and tenant lease analysis.<br />

This occurred in three situations:<br />

(a) a compliant business activity<br />

conducted by the tenant at the<br />

leased property where that tenant,<br />

as a larger entity, also conducted<br />

non-compliant business activities at<br />

other locations; (b) a non-compliant<br />

activity conducted at the leased<br />

property; and (c) non-compliant<br />

tenant leases for the leased property.<br />

In this context, it is important to<br />

note that the DJIMI Fatwa and<br />

subsequent fatwa have focused on<br />

the ‘core’ business activities tests<br />

rather than each and every business<br />

activity of a prospective tenant: the<br />

business activities at the property<br />

must be Shari’ah compliant, at least<br />

to the extent of the permissible<br />

variance parameters, and the<br />

‘core’ business of the tenant and<br />

its corporate group must be in<br />

compliant activities. Purification<br />

and cleansing tests have been utilised<br />

to address allowable impermissible<br />

non-interest business activity income<br />

derived from real estate investments,<br />

with an outside tolerance collar (of,<br />

say, 5%).<br />

An early example of non-compliant<br />

activity involved the acquisition of<br />

a large commercial property that<br />

had only one non-compliant tenant,<br />

an automatic teller machine (ATM)<br />

owned and operated by an interestbased<br />

bank. The relevant Shari’ah<br />

Board undertook a careful factual<br />

inquiry and determined that, among<br />

other factors, the square footage<br />

and proportionate rent of the ATM<br />

space was minimal relative to the<br />

entirety, there were no Islamic banks<br />

as alternatives, and the business<br />

conducted at the ATM was primarily<br />

non-commercial. The acquisition of<br />

the building and the presence of the<br />

ATM, were permitted. The number<br />

and variety of scenarios involving<br />

non-compliant tenants expanded<br />

quickly and commensurately with<br />

the expansion of Shari’ah-compliant<br />

real estate investments. Consider, as<br />

examples, supermarkets selling pork<br />

and/or alcohol products, restaurants<br />

serving alcohol, the check clearing<br />

operations of an interest-based bank,<br />

and the back-office operations of<br />

insurance companies as but a few of<br />

the myriad of factual scenarios that<br />

have been considered.<br />

www.islamic-banking.com IIBI 13