Bernhard Gräf: US Current account: Undercover improvement

Bernhard Gräf: US Current account: Undercover improvement

Bernhard Gräf: US Current account: Undercover improvement

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong><br />

Fed eased by 325 bp<br />

Fed funds target rate, %<br />

00 02 04 06 08<br />

Source: Fed<br />

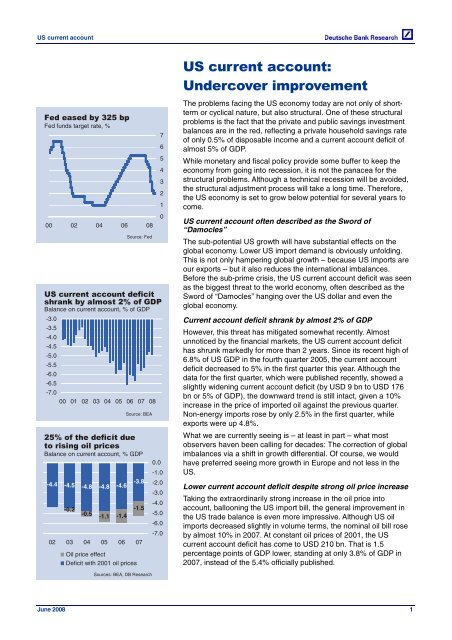

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit<br />

shrank by almost 2% of GDP<br />

Balance on current <strong>account</strong>, % of GDP<br />

-3.0<br />

-3.5<br />

-4.0<br />

-4.5<br />

-5.0<br />

-5.5<br />

-6.0<br />

-6.5<br />

-7.0<br />

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08<br />

Source: BEA<br />

25% of the deficit due<br />

to rising oil prices<br />

Balance on current <strong>account</strong>, % GDP<br />

-4.4 -4.5 -4.8 -4.8 -4.6<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.5<br />

-1.1 -1.4<br />

-3.8<br />

-1.5<br />

02 03 04 05 06 07<br />

Oil price effect<br />

Deficit with 2001 oil prices<br />

Sources: BEA, DB Research<br />

0.0<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

-1.0<br />

-2.0<br />

-3.0<br />

-4.0<br />

-5.0<br />

-6.0<br />

-7.0<br />

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong>:<br />

<strong>Undercover</strong> <strong>improvement</strong><br />

The problems facing the <strong>US</strong> economy today are not only of shortterm<br />

or cyclical nature, but also structural. One of these structural<br />

problems is the fact that the private and public savings investment<br />

balances are in the red, reflecting a private household savings rate<br />

of only 0.5% of disposable income and a current <strong>account</strong> deficit of<br />

almost 5% of GDP.<br />

While monetary and fiscal policy provide some buffer to keep the<br />

economy from going into recession, it is not the panacea for the<br />

structural problems. Although a technical recession will be avoided,<br />

the structural adjustment process will take a long time. Therefore,<br />

the <strong>US</strong> economy is set to grow below potential for several years to<br />

come.<br />

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> often described as the Sword of<br />

“Damocles”<br />

The sub-potential <strong>US</strong> growth will have substantial effects on the<br />

global economy. Lower <strong>US</strong> import demand is obviously unfolding.<br />

This is not only hampering global growth – because <strong>US</strong> imports are<br />

our exports – but it also reduces the international imbalances.<br />

Before the sub-prime crisis, the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit was seen<br />

as the biggest threat to the world economy, often described as the<br />

Sword of “Damocles” hanging over the <strong>US</strong> dollar and even the<br />

global economy.<br />

<strong>Current</strong> <strong>account</strong> deficit shrank by almost 2% of GDP<br />

However, this threat has mitigated somewhat recently. Almost<br />

unnoticed by the financial markets, the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit<br />

has shrunk markedly for more than 2 years. Since its recent high of<br />

6.8% of <strong>US</strong> GDP in the fourth quarter 2005, the current <strong>account</strong><br />

deficit decreased to 5% in the first quarter this year. Although the<br />

data for the first quarter, which were published recently, showed a<br />

slightly widening current <strong>account</strong> deficit (by <strong>US</strong>D 9 bn to <strong>US</strong>D 176<br />

bn or 5% of GDP), the downward trend is still intact, given a 10%<br />

increase in the price of imported oil against the previous quarter.<br />

Non-energy imports rose by only 2.5% in the first quarter, while<br />

exports were up 4.8%.<br />

What we are currently seeing is – at least in part – what most<br />

observers haven been calling for decades: The correction of global<br />

imbalances via a shift in growth differential. Of course, we would<br />

have preferred seeing more growth in Europe and not less in the<br />

<strong>US</strong>.<br />

Lower current <strong>account</strong> deficit despite strong oil price increase<br />

Taking the extraordinarily strong increase in the oil price into<br />

<strong>account</strong>, ballooning the <strong>US</strong> import bill, the general <strong>improvement</strong> in<br />

the <strong>US</strong> trade balance is even more impressive. Although <strong>US</strong> oil<br />

imports decreased slightly in volume terms, the nominal oil bill rose<br />

by almost 10% in 2007. At constant oil prices of 2001, the <strong>US</strong><br />

current <strong>account</strong> deficit has come to <strong>US</strong>D 210 bn. That is 1.5<br />

percentage points of GDP lower, standing at only 3.8% of GDP in<br />

2007, instead of the 5.4% officially published.<br />

June 2008 1

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong><br />

Price of imported oil<br />

quadrupled<br />

<strong>US</strong>D/bbl.<br />

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08<br />

0<br />

Source: BEA<br />

<strong>US</strong>D depreciated by 10%<br />

in 2007<br />

Nominal effective <strong>US</strong>D exchange rate<br />

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08<br />

Growth differential<br />

widened<br />

Real GDP, % yoy<br />

World (ex <strong>US</strong>A)<br />

<strong>US</strong>A<br />

Source: IMF<br />

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

120<br />

110<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

Sources: IMF, BEA, DB Research<br />

5.0<br />

4.0<br />

3.0<br />

2.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.0<br />

Drivers of the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong><br />

What will happen in the years to come? The <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> is<br />

mainly driven by<br />

1. the growth differential between the United States and its main<br />

trading partners<br />

2. the <strong>US</strong> dollar exchange rate and<br />

3. the development of the oil price.<br />

Let’s start with the last argument, the oil price. Assuming that the oil<br />

price will not rise further, the <strong>US</strong> oil import bill will stabilise, lowering<br />

pressure on the current <strong>account</strong>. However, oil price forecasts are<br />

highly uncertain and a further rise in the oil price cannot be ruled<br />

out. The two other factors, however, both point to a further reduction<br />

in the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit in the foreseeable future.<br />

<strong>US</strong> dollar depreciation and growth differential: further<br />

<strong>improvement</strong> of the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> in the pipeline<br />

The depreciation of the <strong>US</strong> dollar usually works through the current<br />

<strong>account</strong> with a time lag of up to one year. Therefore, last year’s<br />

decline in the <strong>US</strong> dollar of a good 10% against the euro and on a<br />

trade-weighted basis will improve this year’s <strong>US</strong> trade balance. A<br />

model calculation shows that a 10% depreciation of the <strong>US</strong> dollar on<br />

a trade-weighted basis reduces the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit by<br />

around ½% of GDP. So, a further reduction in the <strong>US</strong> current<br />

<strong>account</strong> deficit is on the cards.<br />

Let me now discuss the effects of the growth differential on the<br />

current <strong>account</strong> balance, which takes me back to my starting point.<br />

According to our calculation, a negative growth differential between<br />

the <strong>US</strong> and its main trading partners of one percentage point<br />

(meaning that <strong>US</strong> GDP growth is one percentage point lower than in<br />

the rest of the world) would improve the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit<br />

by ½% of GDP. Given slow <strong>US</strong> growth in the years to come a growth<br />

differential of around one percentage point is possible in the period<br />

2008 to 2010.<br />

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit will shrink to below 4% in 2010 …<br />

All in all, this would reduce the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit to below<br />

4% of GDP by 2010. In the literature, a current <strong>account</strong> deficit of 3 to<br />

4% of GDP is usually regarded as a sustainable level. With a<br />

permanent current <strong>account</strong> deficit of 3% of GDP, the external debt to<br />

GDP ratio would stabilise at around 60%. Assuming this, no vicious<br />

circle of the sort that the current <strong>account</strong> deficit is leading to rising<br />

external debt, rising debt payments and again to a rising current<br />

<strong>account</strong> deficit will result.<br />

… but no stable equilibrium in sight<br />

However, despite such marked <strong>improvement</strong> in the <strong>US</strong> current<br />

<strong>account</strong>, no stable equilibrium is in sight. The reason is that the socalled<br />

Houthakker-Magee asymmetry, which describes the fact that<br />

the <strong>US</strong> import more than their main trading partner per percentage<br />

point of growth, permanently deteriorates the trade balance.<br />

In order to compensate the pressure on the trade balance caused<br />

by the Houthakker-Magee asymmetry, the <strong>US</strong> dollar would need to<br />

decline permanently. But given our experience over the last decade,<br />

I would warn against making such a prediction.<br />

June 2008 2

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong><br />

Growth differential driving<br />

<strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit<br />

%-points (left), % GDP (right)<br />

4<br />

-2.0<br />

3<br />

-1.5<br />

2<br />

-1.0<br />

1<br />

-0.5<br />

0<br />

0.0<br />

-1<br />

0.5<br />

-2<br />

1.0<br />

-3<br />

1.5<br />

-4<br />

2.0<br />

70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05<br />

Growth differential <strong>US</strong>A vs.<br />

OECD (left)<br />

Change in the current <strong>account</strong><br />

balance as % of GDP (right)<br />

Quelle: BEA, OECD<br />

The two sides of a coin: strength or weakness of the <strong>US</strong><br />

economy<br />

This brings me to my last point and the question as to whether the<br />

current <strong>account</strong> deficit is a sign of <strong>US</strong> economic strength or<br />

weakness. The answer has major implications for the <strong>US</strong> dollar.<br />

The question is equivalent to “which drives which”? Is the trade<br />

balance driving the capital <strong>account</strong> or vice versa? Seen from a trade<br />

perspective, the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit materialised because the<br />

<strong>US</strong> economy consumes more than it produces. This is often seen as<br />

the weakness of the <strong>US</strong> economy implying that the <strong>US</strong> is living<br />

beyond its means, especially if – as in the case of the <strong>US</strong> – the<br />

spending is primarily consumption.<br />

The approach from the capital <strong>account</strong> perspective, on the other<br />

hand, regards the strength of the <strong>US</strong> economy and the resultant<br />

capital flows as the cause of the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong> deficit. Owing<br />

to the attractiveness of the <strong>US</strong> economy as an investment location<br />

and the expectations of higher returns, capital flows into the <strong>US</strong> will<br />

rise, which tends to boost the value of the <strong>US</strong> dollar. If an economy<br />

enjoys net capital inflows it – ceteris paribus – needs to have a<br />

current <strong>account</strong> deficit. As a result of the stronger <strong>US</strong> dollar, imports<br />

become cheaper in the <strong>US</strong>, boosting demand for imports and<br />

deteriorating the current <strong>account</strong> balance further.<br />

In my view the truth with regard to this question is a moving target.<br />

Sometimes it seems that the trade perspective holds true, while in<br />

other periods (during the new economy era for example) the capital<br />

<strong>account</strong> was driving the <strong>US</strong> current <strong>account</strong>. This makes it virtually<br />

impossible to integrate the current <strong>account</strong> as an explanatory into<br />

<strong>US</strong> dollar exchange rate models. Which on the other hand is quite<br />

convenient for fx-strategists as the can play the current <strong>account</strong><br />

argument whatever way just suits them.<br />

<strong>Bernhard</strong> <strong>Gräf</strong>, +49 69 910-31738 (bernhard.graef@db.com)<br />

June 2008 3