Java.Mar.2016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

from the 1920s—a community that never existed—<br />

basically all lies. Tactical Urbanism is a catch phrase<br />

referring to many different attempts by architects<br />

over the last 10 years to help people take action to<br />

make their own communities better.<br />

One group that I worked with on a book project was<br />

Urban-Think Tank. They got their start in Caracas,<br />

Venezuela, driving around with a car tape saying,<br />

“We’re architects. What do you need? We’re here to<br />

help.” They got very involved with the favelas over<br />

there, working on various projects—small additions<br />

to open up closed parts of the city—interventions.<br />

Often the trick is to figure out what is the minimum<br />

that you can do to create an impact—guerilla<br />

landscaping, for example, like planting flowers on<br />

vacant lands.<br />

You were trained as an architect but are known<br />

as more of a critic and curator. Do you practice<br />

architecture?<br />

I pretend (laughs). Yes, I entered a competition in<br />

Taiwan last year. Didn’t win. I’ve done many things:<br />

practiced architecture, worked as a curator, critic,<br />

professor, assembled books and was the director of<br />

an art museum. I have many different perspectives.<br />

10 JAVA<br />

MAGAZINE<br />

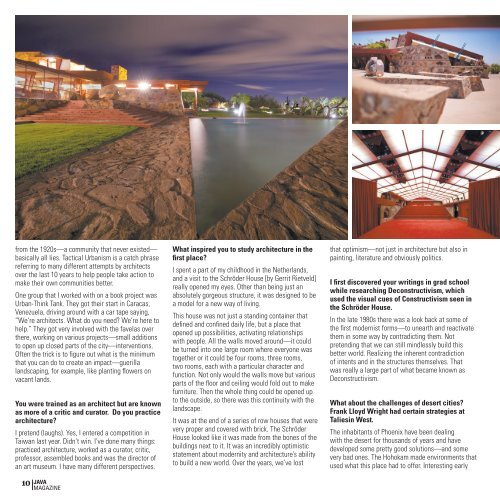

What inspired you to study architecture in the<br />

first place?<br />

I spent a part of my childhood in the Netherlands,<br />

and a visit to the Schröder House [by Gerrit Rietveld]<br />

really opened my eyes. Other than being just an<br />

absolutely gorgeous structure, it was designed to be<br />

a model for a new way of living.<br />

This house was not just a standing container that<br />

defined and confined daily life, but a place that<br />

opened up possibilities, activating relationships<br />

with people. All the walls moved around—it could<br />

be turned into one large room where everyone was<br />

together or it could be four rooms, three rooms,<br />

two rooms, each with a particular character and<br />

function. Not only would the walls move but various<br />

parts of the floor and ceiling would fold out to make<br />

furniture. Then the whole thing could be opened up<br />

to the outside, so there was this continuity with the<br />

landscape.<br />

It was at the end of a series of row houses that were<br />

very proper and covered with brick. The Schröder<br />

House looked like it was made from the bones of the<br />

buildings next to it. It was an incredibly optimistic<br />

statement about modernity and architecture’s ability<br />

to build a new world. Over the years, we’ve lost<br />

that optimism—not just in architecture but also in<br />

painting, literature and obviously politics.<br />

I first discovered your writings in grad school<br />

while researching Deconstructivism, which<br />

used the visual cues of Constructivism seen in<br />

the Schröder House.<br />

In the late 1980s there was a look back at some of<br />

the first modernist forms—to unearth and reactivate<br />

them in some way by contradicting them. Not<br />

pretending that we can still mindlessly build this<br />

better world. Realizing the inherent contradiction<br />

of intents and in the structures themselves. That<br />

was really a large part of what became known as<br />

Deconstructivism.<br />

What about the challenges of desert cities?<br />

Frank Lloyd Wright had certain strategies at<br />

Taliesin West.<br />

The inhabitants of Phoenix have been dealing<br />

with the desert for thousands of years and have<br />

developed some pretty good solutions—and some<br />

very bad ones. The Hohokam made environments that<br />

used what this place had to offer. Interesting early