Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

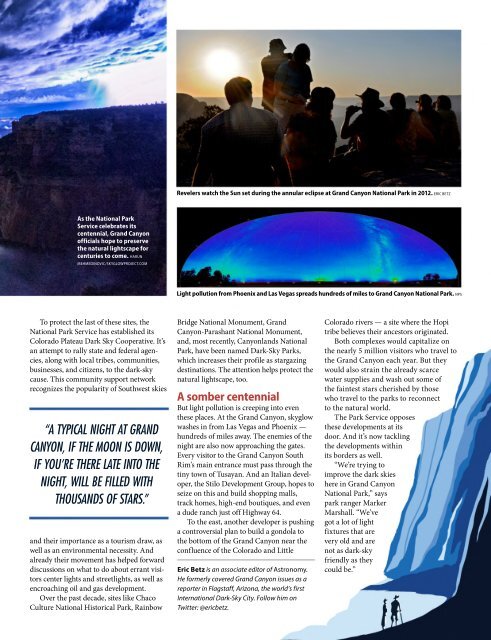

Revelers watch the Sun set during the annular eclipse at Grand Canyon National Park in 2012. ERIC BETZ<br />

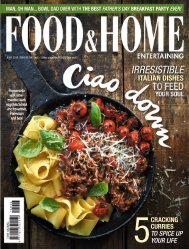

As the National Park<br />

Service celebrates its<br />

centennial, Grand Canyon<br />

officials hope to preserve<br />

the natural lightscape for<br />

centuries to come. HARUN<br />

MEHMEDINOVIC/SKYGLOWPROJECT.COM<br />

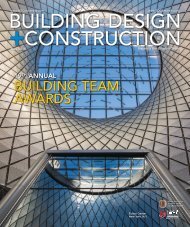

Light pollution from Phoenix and Las Vegas spreads hundreds of miles to Grand Canyon National Park. NPS<br />

To protect the last of these sites, the<br />

National Park Service has established its<br />

Colorado Plateau Dark Sky Cooperative. It’s<br />

an attempt to rally state and federal agencies,<br />

along with local tribes, communities,<br />

businesses, and citizens, to the dark-sky<br />

cause. This community support network<br />

recognizes the popularity of Southwest skies<br />

“A TYPICAL NIGHT AT GRAND<br />

CANYON, IF THE MOON IS DOWN,<br />

IF YOU’RE THERE LATE INTO THE<br />

NIGHT, WILL BE FILLED WITH<br />

THOUSANDS OF STARS.”<br />

and their importance as a tourism draw, as<br />

well as an environmental necessity. And<br />

already their movement has helped forward<br />

discussions on what to do about errant visitors<br />

center lights and streetlights, as well as<br />

encroaching oil and gas development.<br />

Over the past decade, sites like Chaco<br />

Culture National Historical Park, Rainbow<br />

Bridge National Monument, Grand<br />

Canyon-Parashant National Monument,<br />

and, most recently, Canyonlands National<br />

Park, have been named Dark-Sky Parks,<br />

which increases their profile as stargazing<br />

destinations. The attention helps protect the<br />

natural lightscape, too.<br />

A somber centennial<br />

But light pollution is creeping into even<br />

these places. At the Grand Canyon, skyglow<br />

washes in from Las Vegas and Phoenix —<br />

hundreds of miles away. The enemies of the<br />

night are also now approaching the gates.<br />

Every visitor to the Grand Canyon South<br />

Rim’s main entrance must pass through the<br />

tiny town of Tusayan. And an Italian developer,<br />

the Stilo Development Group, hopes to<br />

seize on this and build shopping malls,<br />

track homes, high-end boutiques, and even<br />

a dude ranch just off Highway 64.<br />

To the east, another developer is pushing<br />

a controversial plan to build a gondola to<br />

the bottom of the Grand Canyon near the<br />

confluence of the Colorado and Little<br />

Eric Betz is an associate editor of <strong>Astronomy</strong>.<br />

He formerly covered Grand Canyon issues as a<br />

reporter in Flagstaff, Arizona, the world’s first<br />

International Dark-Sky City. Follow him on<br />

Twitter: @ericbetz.<br />

Colorado rivers — a site where the Hopi<br />

tribe believes their ancestors originated.<br />

Both complexes would capitalize on<br />

the nearly 5 million visitors who travel to<br />

the Grand Canyon each year. But they<br />

would also strain the already scarce<br />

water supplies and wash out some of<br />

the faintest stars cherished by those<br />

who travel to the parks to reconnect<br />

to the natural world.<br />

The Park Service opposes<br />

these developments at its<br />

door. And it’s now tackling<br />

the developments within<br />

its borders as well.<br />

“We’re trying to<br />

improve the dark skies<br />

here in Grand Canyon<br />

National Park,” says<br />

park ranger Marker<br />

Marshall. “We’ve<br />

got a lot of light<br />

fixtures that are<br />

very old and are<br />

not as dark-sky<br />

friendly as they<br />

could be.”