A Champion's Mind - Pete Sampras

www.tennismoscow.me Insta:TENNISMOSCOW

www.tennismoscow.me Insta:TENNISMOSCOW

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Paris was running out. I had plenty of good results to call upon from the past to try to change my own<br />

mind, but that didn’t work. I could neither convince nor fool myself. That Delgado match was the straw<br />

that broke the camel’s back as far as Roland Garros went for me. Even for me, thinking about Roland<br />

Garros raises more questions than it answers.<br />

One thing I know for sure is that the year when I actually made a big effort to do all I could to win in<br />

Paris was a mess. In 1995, I had set up my tournament and training schedule with an eye toward doing<br />

well at Roland Garros. I did it partly to placate critics as well as friends, all of whom thought I had to<br />

target the event if I wanted to unlock its mysteries. The strategy didn’t just backfire, it blew up in my face<br />

when I lost my first match to Gilbert Schaller. Tim and I had expected to make a run in Paris that year, and<br />

the loss really hurt my long-term confidence as a clay-court player.<br />

The situation was perplexing. I periodically put up some fine results on clay (I had won the Italian<br />

Open and Kitzbühel, and led the United States to that key 1995 Davis Cup final win in Moscow), but it<br />

was almost like they came out of the blue. Tim died shortly before the 1996 French Open, and that<br />

inspired me to make what would be my best run there. But let’s face it, that was an extraordinary<br />

circumstance. The cold reality is that after 1996, I was never really a factor in Paris—even if I happened<br />

to go a round or two.<br />

My problems on clay were related to my versatility, and the confidence that was so helpful to me on<br />

hard courts. I could win from the back—I had beaten French Open champs like Jim Courier and Sergi<br />

Bruguera from the baseline. So I was reluctant to heed the advice of Paul and others who thought my only<br />

chance to win was through attacking. Sometimes I did feel obliged to attack, and felt comfortable<br />

embracing that game plan. At other times, I tried to feel my way into matches from the baseline, not<br />

entirely confident but hoping I’d hit upon something that would help me crack the clay-court code.<br />

I never really evolved in Paris, never made progress toward a comfort zone. I was accustomed to<br />

feeling totally in control of my game—that’s how it was at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. On grass and<br />

hard courts, I just had this mentality: bring the gas—serve big, push the action, notch it up, and see if the<br />

other guy can take it. On clay, though, you have to back off the gas a little, even when you’re playing<br />

attacking tennis. You need to be more patient, awaiting your opportunity. I didn’t really feel comfortable<br />

playing within myself that way. When I played well on clay, it was because I was reasonably calm, and<br />

just felt my way around in matches—it wasn’t that different from how I played on hard courts.<br />

But there was always pressure on me, some of it self-imposed, to win in Paris with an attacking game.<br />

A part of me wanted to come in all the time, the way Stefan Edberg did. His daredevil attacking style<br />

carried him all the way to the final one year, which was further than I ever got. But when I rushed the net<br />

behind every decent serve, I’d often feel uncomfortable, like everything was happening too fast. I don’t<br />

think I was a great mover on clay, and that was a subtle factor in my struggles. I found the surface was a<br />

little slippery and uncertain underfoot, so I played a little too upright, at least compared to a guy like<br />

Yannick Noah (the Frenchman who won Roland Garros by attacking the net in 1983). Noah played from<br />

this crouch, like a big cat always ready to pounce. I was often ill at ease, even up at the net.<br />

Paul was always after me to attack the net in Paris, but I resisted his advice. In fact, the year I beat Jim<br />

from the backcourt, it was as much to prove my point to Paul as anything else. But the reality was that I<br />

couldn’t win from the back consistently enough to beat the very top players in the three or four successive<br />

rounds it takes to win a major. One year, I decided to embrace the chip-and-charge strategy that Paul<br />

thought might work, but I was picked apart by Andrei Medvedev. So much for that.<br />

Clay gave my opponents additional advantages. They could expose my backhand—my weaker shot—by<br />

getting to it with high-bouncing balls. Having to hit those high backhands gives one-handed backhanders<br />

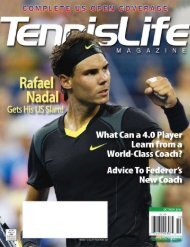

fits—just look at the problems Roger Federer has had on clay with Rafael Nadal. In Roger’s case, the<br />

problem is exacerbated by the fact that Nadal is a southpaw. Late in my career, technology was also<br />

starting to catch up with me. I played my entire career with that extremely small-headed racket. Not only