Ecology and Farming

Ecology and Farming

Ecology and Farming

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

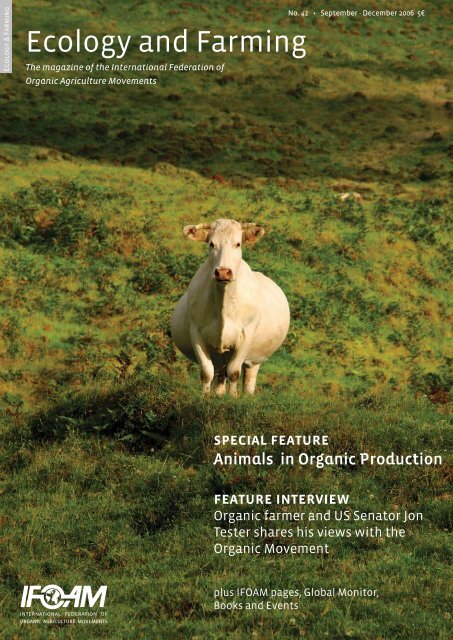

<strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong><br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong><br />

The magazine of the International Federation of<br />

Organic Agriculture Movements<br />

No. 41 • September - December 2006 5€<br />

Special Feature<br />

Animals in Organic Production<br />

Feature interview<br />

Organic farmer <strong>and</strong> US Senator Jon<br />

Tester shares his views with the<br />

Organic Movement<br />

plus IFOAM pages, Global Monitor,<br />

Books <strong>and</strong> Events

Note the date<br />

Nuremberg, Germany<br />

BioFach 2008<br />

World Organic Trade Fair<br />

Where organic people meet<br />

21 – 24.2.2008<br />

Organizer<br />

NürnbergMesse<br />

Tel +49(0)9 11. 86 06-0<br />

Fax+49(0)9 11. 86 06-82 28<br />

info@nuernbergmesse.de<br />

www.biofach.com<br />

Patron of BioFach<br />

International Federation<br />

of Organic Agriculture<br />

Movements

RAPUNZEL has more than 30 years<br />

of experience in importing,<br />

processing <strong>and</strong> distributing the<br />

finest organic certified food<br />

worldwide.<br />

RAPUNZEL promotes organic<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> manages its own<br />

projects in Turkey (dried fruit <strong>and</strong><br />

nuts), Spain (olives <strong>and</strong> almonds)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sri Lanka (coconut).<br />

Additionally, we assist organic<br />

projects in more than 20 countries<br />

throughout the world, for example<br />

in Brazil (cane sugar), Bolivia<br />

(cocoa, Brazil nuts, quinoa), Costa<br />

Rica (cane sugar, dried bananas),<br />

the Dominican Republic (cocoa <strong>and</strong><br />

coffee) <strong>and</strong> Tanzania (coffee).<br />

For complete information contact: RAPUNZEL NATURKOST AG • Rapunzelstr. 1 • D-87764 Legau, Germany • Phone: + 49-8330-529-1133 • Fax: + 49-8330-529-1139 • www.rapunzel.de<br />

��������<br />

Consultancy • Intelligence • Marketing<br />

Project design • Certifi cation development<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ards development • Advanced training<br />

’There is not one developed <strong>and</strong><br />

one underdeveloped world.<br />

There is only one world<br />

that is badly developed’<br />

Always ahead in development<br />

We pioneer new areas <strong>and</strong> concepts in the organic sector. We develop<br />

in-house quality assurance systems, <strong>and</strong> are innovators in new product<br />

areas such as organic wild production <strong>and</strong> fi sheries. We conduct<br />

training programmes for sector leaders <strong>and</strong> policy makers. We also<br />

have considerable long-term experience with the organic market.<br />

We enjoy to find new ways (or discover old ways) to guarantee the<br />

organic integrity.<br />

�������<br />

www.grolink.se<br />

Serving the organic world<br />

info@grolink.se • www.grolink.se • Address: Torfolk, SE-684 95 Höje, Sweden • Phone: +46 563 723 45 • Fax: +46 563 720 66<br />

The Organic St<strong>and</strong>ard is a monthly journal published by Grolink. Distributed by email as a pdf fi le<br />

the journal deals with issues concerning international organic st<strong>and</strong>ards, regulations <strong>and</strong> certifi cation.<br />

For information or subscription: offi ce@organicst<strong>and</strong>ard.com • www.organicst<strong>and</strong>ard.com • Phone: +46 563 723 45

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> is the English<br />

language magazine of the International<br />

Federation of Organic Agriculture<br />

Movements (IFOAM).<br />

ISSN No. 1016-5061<br />

Imprint<br />

IFOAM Head Office:<br />

Charles-de-Gaulle-Str. 5<br />

53115 Bonn<br />

Germany.<br />

Tel: +49 - 228 - 926 - 5010<br />

Fax: +49 - 228 - 926 - 5099<br />

Email: headoffice@ifoam.org<br />

www.ifoam.org<br />

Commissioning Editor:<br />

Neil Sorensen<br />

Letters to the Editor:<br />

All articles <strong>and</strong> correspondence solely<br />

concerned with <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> should<br />

be sent to letters@ifoam.org<br />

Subscriptions <strong>and</strong> advertisements: All<br />

subscription <strong>and</strong> advertising queries should<br />

be directed to the IFOAM Head Office.<br />

Subscription Rate (6 issues/two years): 25<br />

Euros; One may subscribe via the IFOAM<br />

webshop or by contacting the IFOAM Head<br />

Office.<br />

Reprints: Permission is granted to reproduce<br />

original articles providing the credit is given<br />

as follows:<br />

‘Reprinted with permission from <strong>Ecology</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong>, IFOAM, Charles-de-Gaulle-Str. 5,<br />

53113, Bonn, Germany.’<br />

Contributions: Articles sent for inclusion in<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> should be no longer<br />

than 1500 words. They should be sent by<br />

email to n.sorensen@ifoam.org. If this is not<br />

possible, a copy can be faxed or sent by post.<br />

Authors are responsible for the content of<br />

their own articles. Their opinions do not<br />

necessarily express the views of IFOAM.<br />

Cover Photograph: © Rui Vale Sousa<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Editorial 5<br />

IFOAM Pages<br />

East African Organic Product St<strong>and</strong>ard Approved by the East African<br />

Community 6<br />

1st IFOAM International Conference on Marketing of Organic <strong>and</strong><br />

Regional Values 7<br />

FAO Organizes Conference on Organic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Food Security 8<br />

Information <strong>and</strong> Important Dates for the 2008 IFOAM General Assembly 8<br />

Call for Nomination of C<strong>and</strong>idates to the IFOAM World Board 9<br />

Call for Papers for the 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress 10<br />

Organic Day(s) in the Mediterranean area 11<br />

IFOAM Opens a Regional Office in Latin America 12<br />

IFOAM Thanks Donors for Their Generous Support 12<br />

Feature Interview<br />

Organic Farmer <strong>and</strong> US Senator Jon Tester Shares His Views with the<br />

Organic Movement 14<br />

Special Feature: Animals in Organic Production<br />

Fostering Organic Livestock Research - Priorities <strong>and</strong> Preferences<br />

Animals in an Organic System: Exploring the Ecological, Social <strong>and</strong><br />

20<br />

Economic Functions of Animals in Organic Agriculture 26<br />

Animals in Translation 33<br />

Contribution of Farmer Participation to Research in Organic<br />

Livestock Production 35<br />

Effect of Conventional <strong>and</strong> Organic Production Practices on the<br />

Prevalence <strong>and</strong> Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter in Poultry 39<br />

Global Monitor<br />

“Organic” Salmon - a Leap Too Far? 46<br />

EU Regulation: New Organic Regulation Approved in Principle 48<br />

Ongoing Trends, New Institutions <strong>and</strong> Issues in the US Organic Movement 51<br />

IFOAM Publications 54<br />

Other Publications 56<br />

Calendar of Events 57<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006

Editorial<br />

Truly Sustainable<br />

After a few months’ hiatus, <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> is back in action, with<br />

new features <strong>and</strong> superb content.<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> will now be published in a fully featured electronic<br />

format to better serve your needs in our changing world. With interactive<br />

links throughout the magazine, you can instantly connect with<br />

advertisers or authors, or contribute editorial messages by clicking on the<br />

conveniently provided links.<br />

In addition, IFOAM continues to strive towards reducing its carbon<br />

footprint on the planet <strong>and</strong> adhere to the Principles of Organic Agriculture<br />

to the maximum extent possible, <strong>and</strong> going electronic with <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Farming</strong> is a great way to bring us more towards ecological sustainability.<br />

This issue includes diverse news about IFOAM’s activities, such as the<br />

launch of the East African Organic Product St<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong> related mark,<br />

IFOAM’s upcoming conferences the 1st IFOAM International Conference<br />

on the Marketing of Organic <strong>and</strong> Regional Values <strong>and</strong> the 16th IFOAM<br />

Organic World Congress “Cultivate the Future” in Modena in 2008, <strong>and</strong><br />

the establishment of an IFOAM office in Latin America.<br />

This <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Farming</strong> also has an exclusive interview with organic<br />

farmer <strong>and</strong> US Senator Jon Tester, who gave us the opportunity to hear<br />

firsth<strong>and</strong> about his experiences <strong>and</strong> perspectives on organic farming.<br />

Moreover, as a result of IFOAM’s first conference on animals in organic<br />

production that was held last autumn, we are featuring animals in organic<br />

production, with articles by Dr. Fred Kirschenmann, Distinguished Fellow<br />

for the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University<br />

<strong>and</strong> Temple Gr<strong>and</strong>in, renowned author of Animals In Translation, among<br />

many other excellent contributions.<br />

Thank you for your continued support of IFOAM’s magazine. Don’t<br />

forget that you’re always invited to submit articles, editorials <strong>and</strong> other<br />

contributions for the magazine.<br />

angela B. caudle<br />

IFOAM Executive Director<br />

email: a.caudle@ifoam.org<br />

Editorial

IFOAM News<br />

New St<strong>and</strong>ard for East African<br />

Organic Products Launched<br />

A uniform set of procedures for growing <strong>and</strong> marketing<br />

organic produce has been established for East Africa The<br />

East African Organic Products St<strong>and</strong>ard (EAOS) is the<br />

second regional organic st<strong>and</strong>ard in the world, following<br />

that developed by the European Union. The EAOS <strong>and</strong><br />

associated East African Organic Mark will ensure to<br />

consumers that produce so labeled has been grown in<br />

accordance with a st<strong>and</strong>ardized method based on traditional<br />

methods supplemented by scientific knowledge, <strong>and</strong> based<br />

on ecosystem management rather than the use of artificial<br />

fertilizers <strong>and</strong> pesticides. As organic produce generally sells<br />

at premium prices in rapidly growing overseas markets, it is<br />

hoped that the st<strong>and</strong>ard will increase sales <strong>and</strong> profits for<br />

small farmers in the region.<br />

The st<strong>and</strong>ard was developed by a public-private sector<br />

partnership in East Africa, supported by the UNEP-UNCTAD<br />

Capacity Building Task Force on Trade, Environment <strong>and</strong><br />

Development (CBTF), a joint initiative of the United Nations<br />

Conference on Trade <strong>and</strong> Development (UNCTAD) <strong>and</strong><br />

the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), <strong>and</strong><br />

IFOAM.<br />

Tanzanian Prime Minister Edward N. Lowassa presented the<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong> organic mark on May 29th during a week-long<br />

series of meetings <strong>and</strong> workshops titled “East African Organic<br />

Conference: Unleashing the Potential of Organic Agriculture.”<br />

Also on May 29th, Secretaries of Agriculture <strong>and</strong> other high-<br />

level government officials from Kenya, Tanzania, Ug<strong>and</strong>a,<br />

Rw<strong>and</strong>a, <strong>and</strong> Burundi took part in a roundtable discussion<br />

on “Unleashing the Potential of Organic Agriculture in East<br />

Africa.”<br />

The conference was jointly organized by the CBTF, IFOAM,<br />

the Tanzania Organic Agriculture Movement (TOAM) <strong>and</strong><br />

Export Promotion of Organic Products from Africa (EPOPA),<br />

in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture, Food <strong>and</strong><br />

Cooperatives of United Republic of Tanzania, the Food <strong>and</strong><br />

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), <strong>and</strong><br />

the International Trade Centre (UNCTAD/World Trade<br />

Organization (WTO)).<br />

Work on the East African Organic Product St<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

has been made possible by financial support from the<br />

European Commission, the Swedish International Agency<br />

for Development Cooperation (Sida), <strong>and</strong> the Government<br />

of Norway. EAOPS-related documents are available at the<br />

following websites:<br />

IFOAM Africa Office Coordinator Hervé Bouagnimbeck discusses IFOAM‘s activities in Africa with Tanzanian Prime Minister Edward N.<br />

Lowassa.<br />

www.ifoam.org/partners/projects/osea.html<br />

www.unep-unctad.org/cbtf/projecteastafrica.asp<br />

The East African Organic Mark will be help to<br />

make organic products widely identifiable<br />

throughout East Africa.<br />

IFOAM – News <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr -DEcEmbEr 2006

1 ST IFOAM INTErNATIONAL<br />

CONFErENCE ON MArkETING OF<br />

OrGANIC ANd rEGIONAL VALuES<br />

Organized by<br />

Organic Services <strong>and</strong> Ecol<strong>and</strong><br />

in cooperation with IFOAM.<br />

AuGuST 26 – 28, 2007<br />

SChwäbISCh hALL, GErMANy<br />

register at www.ifoam.org<br />

This conference will focus on a discussion of specific<br />

marketing strategies that aim to give value to products by<br />

taking into consideration their uniqueness. It will deal with<br />

the question of how to create <strong>and</strong> identify regional <strong>and</strong><br />

other specific values, <strong>and</strong> ultimately how to translate these<br />

values into successful marketing strategies for organic<br />

products. Communicating these values to the consumer is<br />

part of that strategy. The conference will consider various<br />

concepts <strong>and</strong> marketing strategies, including regulatory<br />

approaches, to protect regional values <strong>and</strong> traditional<br />

knowledge.<br />

The conference goal is to initiate <strong>and</strong> foster the discussion<br />

<strong>and</strong> knowledge about marketing of organic <strong>and</strong> regional<br />

values, respective tools <strong>and</strong> frameworks.<br />

The main objectives of the conference are to:<br />

• Create awareness among organic stakeholders<br />

involved in organic marketing for additional values<br />

<strong>and</strong> ways of marketing these values<br />

• Initiate thinking about new approaches, especially<br />

among farmers <strong>and</strong> their representatives<br />

• Discuss <strong>and</strong> review successful examples<br />

• Identify challenges <strong>and</strong> opportunities for the<br />

sector<br />

• Information exchange <strong>and</strong> networking<br />

Cooperating Partner<br />

Main Sponsor<br />

Silver Sponsors<br />

bronze Sponsors<br />

basic Sponsors<br />

Media Partner<br />

Organizer<br />

Organic Services GmbH<br />

L<strong>and</strong>sberger Str. 527<br />

81241 München, Germany<br />

Tel: +49 (0) 89 820 759-07<br />

Fax: +49 (0) 89 820 759-19<br />

Email: ifoam.conference0708@organic-services.com<br />

www.organic-services.com<br />

IFOAM – News

FAO Conference on Organic<br />

Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Food Security<br />

From May 3rd to 5th 2007, the FAO organized a conference<br />

on Organic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Food Security.<br />

The overall objective of the Conference was to shed light on<br />

the contribution of Organic Agriculture to food security,<br />

through the analysis of existing information of the agro-<br />

ecological areas of the world. The Conference identified<br />

Organic Agriculture’s potential <strong>and</strong> limits in addressing the<br />

food security challenge, including conditions required for its<br />

success.<br />

The outcome of the conference provided a thorough<br />

assessment of the state of knowledge on Organic Agriculture<br />

<strong>and</strong> food security, including recommendations on areas for<br />

further research <strong>and</strong> policy development. The Report of the<br />

Conference subsequently was submitted to the 33rd Session<br />

of the Committee on Food Security, for information <strong>and</strong><br />

further action.<br />

IFOAM was a partner in organizing the conference, <strong>and</strong> had<br />

both an official role in the steering committee <strong>and</strong> sponsored<br />

members to contribute to the conference.<br />

Conference report: http://www.fao.org/organicag/ofs/<br />

index_en.htm<br />

Conference Press Releases: http://www.fao.org/organicag/<br />

ofs/press_en.htm<br />

Information <strong>and</strong> Import <strong>and</strong><br />

Dates for the 200 IFOAM<br />

General Assembly<br />

The IFOAM General Assembly convenes once every three<br />

years in conjunction with the IFOAM Organic World<br />

Congress. It is the democratic decision making forum for the<br />

international organic movement.<br />

The IFOAM General Assembly is a very dynamic <strong>and</strong> lively<br />

gathering, inspiring IFOAM members, board <strong>and</strong> staff to<br />

work towards IFOAM’s mission.<br />

At the upcoming General Assembly in Modena, Italy from<br />

June 22-24 2008, the organic movement ‘in its full diversity’<br />

from all over the world will deliberate upon the challenges<br />

<strong>and</strong> opportunities for the future.<br />

The work <strong>and</strong> achievements during the current term of<br />

the World Board will be presented in a special World Board<br />

report at the General Assembly. The Executive Director<br />

will explain how the Head Office staff, committees <strong>and</strong> task<br />

forces contributed to the work that has been accomplished.<br />

Additionally, reports about IFOAM’s cooperation with<br />

governments, international NGOs will be given, <strong>and</strong><br />

conclusions <strong>and</strong> reports from IFOAM conferences <strong>and</strong> events<br />

that took place in the intervening years since the last General<br />

Assembly will be discussed.<br />

Important Dates<br />

Deadline for Motions from IFOAM Members:<br />

February 23, 2008<br />

Your deadline for World Board C<strong>and</strong>idacy:<br />

March 22, 2008<br />

Deadline for Bids to organize the IFOAM Organic World<br />

Congress 2011<br />

March 22, 2008<br />

Deadline for Agenda <strong>and</strong> Motions to be Mailed Out to<br />

Members:<br />

April 23, 2008<br />

IFOAM – News <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr -DEcEmbEr 2006

Call for nomination of<br />

c<strong>and</strong>idates for the<br />

IFOAM World Board<br />

At the General Assembly in Modena, Italy, from June 22-24,<br />

2008, a new IFOAM World Board will be elected.<br />

Ten positions are open to be filled. The IFOAM World Board<br />

decides all issues not yet determined by the General Assembly<br />

<strong>and</strong> is responsible to the General Assembly. Election to the<br />

World Board means a challenging opportunity to work for the<br />

further development of the worldwide organic movement.<br />

It can open new horizons <strong>and</strong> enrich the lives of those who<br />

serve.<br />

Any person may present a c<strong>and</strong>idacy for the IFOAM World<br />

Board if the requirements for c<strong>and</strong>idates are fulfilled.<br />

Requirements for World Board c<strong>and</strong>idates:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate is able to prepare for <strong>and</strong> attend World<br />

Board meetings <strong>and</strong> to participate in the work of the<br />

World Board (about 20 working days per year).<br />

C<strong>and</strong>idates shall indicate whether they are also available<br />

to serve on the Executive Board; those c<strong>and</strong>idates<br />

prepared to serve on the Executive Board must be<br />

able to dedicate approximately three months per year<br />

commitment to the interests of IFOAM.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate has good communication skills.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate is willing to look <strong>and</strong> step beyond one’s<br />

personal interests.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idacy is endorsed by 5 IFOAM members in<br />

writing.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate is able to speak <strong>and</strong> read English.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate writes a c<strong>and</strong>idacy statement no longer<br />

than one page (or 500 words) containing:<br />

*<br />

a short curriculum vitae focused on her/his activities<br />

*<br />

in the organic movement<br />

a short description of the area in which (s)he would<br />

particularly like to contribute to the work of the<br />

WorldBoard <strong>and</strong> optionally may give her/his opinion<br />

on major IFOAM positions <strong>and</strong> the IFOAM program<br />

for the coming term.<br />

The c<strong>and</strong>idate submits a photograph, suitable for publication<br />

(300dpi ,in color, .tiff).<br />

Generally, all activities for the IFOAM World Board are<br />

voluntary, with no time reimbursement foreseen, unless<br />

specified otherwise by World Board decisions. When<br />

necessary, travel <strong>and</strong> accommodation costs will be borne by<br />

IFOAM.<br />

Please send your application to the IFOAM Head Office to the<br />

attention of Thomas Cierpka, t.cierpka@ifoam.org. Women,<br />

farmer representatives <strong>and</strong> people from so-called Third World<br />

countries are especially encouraged to consider presenting<br />

their c<strong>and</strong>idacies.<br />

Please note that although geographic, gender, <strong>and</strong> expertise<br />

balance is desired in the World Board, its members are not<br />

elected to represent specific regions, countries, or<br />

organizations, but rather the global interests of the organic<br />

movement.<br />

C<strong>and</strong>idates will be presented in IFOAM -In Action <strong>and</strong> to the<br />

General Assembly.<br />

The deadline for applications is March 22, 2008.<br />

IFOAM – News

cAll for contributionS<br />

tHemeS of tHe orGAnic<br />

WorlD conGreSS<br />

The Organic World Congress has two main tracks: the Systems<br />

Values Track for presentation <strong>and</strong> exchange of practical<br />

experiences from farmers, consumers, campaigns <strong>and</strong><br />

cooperation; <strong>and</strong> a Scientific Research Track, where current<br />

academic research <strong>and</strong> others will be presented <strong>and</strong> discussed.<br />

The following subjects are brought to your attention in order<br />

to receive contributions for both tracks. However, the Congress<br />

won’t be limited only to them <strong>and</strong> contributions are sought<br />

for all themes that are based on the Principles of Organic<br />

Agriculture:<br />

• Education <strong>and</strong> Organic Agriculture<br />

• Organic food quality<br />

• Renewable energy, including biofuel production in<br />

Organic Agriculture, energy <strong>and</strong> rural communities,<br />

mitigation <strong>and</strong> adaptation to climate change <strong>and</strong><br />

carbon sink potentials of Organic Agriculture<br />

• Best practices in organic production <strong>and</strong> animal<br />

husb<strong>and</strong>ry<br />

• Organic food production chain, including processing,<br />

conditioning <strong>and</strong> packaging<br />

• Organic seeds <strong>and</strong> breeds<br />

• Organic markets, including: mainstream distribution,<br />

direct markets, public catering, creating new local <strong>and</strong><br />

regional markets, international/national regulations<br />

<strong>and</strong> trade barriers<br />

• Organic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> rural tourism<br />

• Organic food security<br />

• Women in Organic Agriculture<br />

• Organic viticulture <strong>and</strong> wine making<br />

• Organic horticulture <strong>and</strong> fruit growing<br />

• Organic textiles <strong>and</strong> fibers, including production,<br />

processing <strong>and</strong> marketing<br />

• Natural cosmetics, body care, ecological detergents<br />

<strong>and</strong> household care<br />

• Organic aquaculture, including: fish welfare, feeding<br />

strategies <strong>and</strong> environmental sustainability<br />

In order to have a rich, diverse <strong>and</strong> effective Organic World<br />

Congress, everybody who is actively engaged in Organic<br />

Agriculture, who Cultivates the Future <strong>and</strong> is willing to<br />

contribute with her/his work to the OWC program is warmly<br />

invited to participate by sending us a paper or poster– without<br />

excluding other forms such as videos, pictures, songs, dance<br />

<strong>and</strong> other artistic works.<br />

SubmiSSion of contributionS<br />

The contribution should consist of a short paper on 4 pages<br />

max (2500 words) including: introduction, methods, results <strong>and</strong><br />

recommendations, conclusions, or implications. Contributions<br />

must be written in English.<br />

Submit contributions using the Organic Eprints archive (www.<br />

orgprints.org). Details on the submission process as well as the<br />

template to be used for layout will be made available by June<br />

30th, 2007 at www.ifoam.org.<br />

For artistic contributions, there is no specific form <strong>and</strong> you are<br />

free to submit any kind of work.<br />

Contributions for the Scientific Research Track will be<br />

evaluated through a peer review system by the International<br />

Society of Organic Agriculture Research, ISOFAR (see specific<br />

guidelines at: www.isofar.org/modena2008), <strong>and</strong> supported by<br />

a specific scientific committee <strong>and</strong> by other relevant research<br />

institutions. Parallel conference programs will be supported by<br />

other dedicated subcommittees involving partner organizations<br />

<strong>and</strong> stakeholders.<br />

Deadline for submission: October 15th, 2007<br />

Conference proceedings: A CD version of the proceedings will<br />

be distributed to all participants of the 16th IFOAM Organic<br />

World Congress free of charge.<br />

Contributions that are accepted for the Scientific Research<br />

Track will be included in 2 printed volumes (papers <strong>and</strong> poster).<br />

Authors will receive a free copy at the conference.<br />

All submitted <strong>and</strong> accepted papers will be made public via the<br />

Organic Eprints Archive.<br />

contributionS timeline<br />

September 15th, 2007: OWC registration brochure<br />

October 15th, 2007: contributions deadline<br />

January 31st, 2008: notification of acceptance <strong>and</strong><br />

of necessary modifications<br />

February 29th, 2008: revised papers submitted<br />

June 16th-17th, 2008: thematic pre-conferences<br />

June 18th-20th, 2008: Organic World Congress<br />

More detailed <strong>and</strong> updated information about the program<br />

<strong>and</strong> OWC registration: www.ifoam.org/modena2008<br />

10 IFOAM – News <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr -DEcEmbEr 2006

Organic Day(s) in the<br />

Mediterranean area<br />

by the IFOAM AgriBioMediterraneo<br />

Regional Board<br />

The idea of an Organic Day in the Mediterranean area is not<br />

entirely new, considering that the Biodomenica (Organic<br />

Sunday) has taken place in Italy for seven years. In 2001,<br />

members of the IFOAM AgriBioMediterraneo Regional Board<br />

at that time decided to promote a Mediterranean Organic Day.<br />

Thus, Organic Day is being celebrated not only in Italy, but<br />

also in Egypt, Croatia, France, Greece <strong>and</strong> Israel, the main idea<br />

being to promote organic food <strong>and</strong> farming among consumers,<br />

farmers <strong>and</strong> policy makers in a public event.<br />

At present, all kinds of activities are organized for Organic Day<br />

by mainly producer organizations <strong>and</strong> certification bodies. In<br />

practice, the idea of establishing a Mediterranean Organic Day<br />

has proven very ambitious, <strong>and</strong> as experience demonstrates,<br />

it is difficult to force one common day upon countries that<br />

not only have organic sectors in very different stages of<br />

development, but diverse economic <strong>and</strong> cultural situations as<br />

well.<br />

This year’s experience<br />

In Italy, Biodomenica activities included social cooperatives<br />

that use organic farming for integration activities, in this sense<br />

representing not only a food market, but also a cultural event<br />

involving organic producers <strong>and</strong> consumers. Promoting more<br />

than organic farming alone, the day addressed the relationship<br />

between Organic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> food security, environment<br />

safeguards, economic development, <strong>and</strong> the important linkage<br />

to the l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

In some events, organic producers with production in or near<br />

natural parks also participated, in an effort to promote the<br />

role of Organic Agriculture <strong>and</strong> protected areas. Additionally,<br />

a promotional campaign was organized by AIAB, Coldiretti<br />

<strong>and</strong> Legambiente, with support of the Italian Ministries of<br />

Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Environment, to promote the quality of local<br />

organic food through a direct meeting between consumers <strong>and</strong><br />

producers: organic markets were organized in 100 locations<br />

throughout Italy.<br />

In Egypt there were more activities <strong>and</strong> more visitors than in<br />

previous years. Due to Ramadan, their Organic Day took place<br />

in November, with the main event taking place at the SEKEM<br />

farm. Nearly 2000 visitors participated, with a program that<br />

included an organic farming <strong>and</strong> Egyptian folklore ceremony.<br />

In Israel, with IBOA as the main organizer, Organic Day was<br />

celebrated in late Spring 2006, which coincides with the<br />

biblical harvest holiday of Shavuot, which by tradition is the<br />

first day of wheat harvest. The day was a gathering of farmers,<br />

producers <strong>and</strong> consumers, which included organic food st<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> educational activities.<br />

In Greece, DIO organized excursions to producers.<br />

Another example of an Organic Day in the Mediterranean is<br />

the Printemps Bio 2006 (Organic Spring) in France, which<br />

has taken place for many years. The national information<br />

campaign for organically grown products encompassed a two-<br />

week period of promotional events.<br />

IFOAM – News<br />

11

Summing up<br />

The celebration of an Organic Day is a very useful tool for the<br />

development of organic farming to connect with consumers<br />

<strong>and</strong> capture the attention of the public at large. As it is difficult<br />

to establish an exclusive organic day or period in countries<br />

with very different social, economic <strong>and</strong> cultural backgrounds,<br />

we suggest two different scenarios: 1) organizing an Organic<br />

Day in each country on a national or autonomous level under<br />

a common criteria, or 2) establishing an International Organic<br />

Day with support of a intergovernmental organization like the<br />

Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, or<br />

linking Organic Days to International Food Day. To achieve<br />

this, it seems more appropriate to think in a wider area than<br />

Mediterranean, with the involvement of IFOAM <strong>and</strong> the whole<br />

Organic Movement.<br />

iFOam agriBiOmediterraneO regiOnal BOard<br />

www.ifoam-abm.com/<br />

IFOAM Regional Office in Latin<br />

America<br />

Beginning on June 1st,<br />

IFOAM is opening a Regional<br />

Office in Latin America to<br />

support the development of<br />

Organic Agriculture in the<br />

region. The office will be<br />

located in Salta, Argentina,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Patricia Flores Escudero<br />

will serve as the IFOAM<br />

representative to Latin<br />

America <strong>and</strong> the Caribbean<br />

on a part-time basis.<br />

Patricia is a specialist in Agroecology <strong>and</strong> Institutional<br />

Development, <strong>and</strong> has been involved in rural development<br />

projects focused on Organic Agriculture for 15 years. She<br />

has been engaged with several national <strong>and</strong> international<br />

NGOs like Red de Agricultura Ecológica del Perú (RAE-Peru),<br />

Institute of Development <strong>and</strong> Environment (IDMA) <strong>and</strong><br />

Movimiento Agroecológico Latinoamericano (MAELA); <strong>and</strong><br />

since 2002 she has been the Coordinator of Latin America<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Caribbean Group of IFOAM (GALCI) . She will work<br />

in close cooperation with staff from the IFOAM Head Office<br />

in Bonn.<br />

Patricia Flores escudero<br />

EMAIL: patriciafloresescudero@gmail.com<br />

IFOAM Thanks Donors for<br />

Their Generous Support<br />

IFOAM would like to take the opportunity to give a big “thank<br />

you“ to following people for their generous donations:<br />

Platinum<br />

Triodosbank, Bo van Elzakker (Agro Eco), Gunnar Rundgren<br />

(Grolink).<br />

12 IFOAM – News <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr -DEcEmbEr 2006<br />

Gold<br />

Volkert Engelsman (EOSTA B. V. Organic Fruits & Vegetables)<br />

Silver<br />

Wolfgang Gutberlet (Tegut), Wiesengold L<strong>and</strong>ei GmbH Co, Al-<br />

ex<strong>and</strong>er Beck (Assoziation Oekologischer Lebensmittelherstell-<br />

er), Jesus Luis Barrera Lozano A, Ulrich Walter (Lebensbaum),<br />

Jan Schrijver (Good Food Foundation), Ong Kung Wai (Humus<br />

Consultancy), Jacqueline Haessig-Alleje, Paolo Steccanella,<br />

Soonthorn Sritawee (River Kwai).<br />

Bronze<br />

Tom Vaclavik (Green marketing), Shi Shi Kai (Heilongjiang<br />

Harvest Farm Foods Co.,Ltd.), Sheldon Weinberg, Daniel Burke<br />

(Pacific Soybean <strong>and</strong> Grain), Punlert Sodsee (Dole Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

Ltd), Patricio Parra, Asha Kachru, Katherine DiMatteo, Nazir<br />

Nahlawi (East Milling), Georg Roesner (Georg Roesner Ver-<br />

triebs GmbH), Hartmut Wöllner (Entwicklungsbüro für ökolo-<br />

gischen L<strong>and</strong>bau Lindenberg), Lilo Massing, Roberto Pinton<br />

(Pinton Organic Consulting), Nadezda Pesic Mlinko (Organic<br />

Control System d.o.o.), Roberto Lughi (Associazione produttori<br />

biologici e biodinamici dell Emilia Romagna), Organic <strong>Farming</strong><br />

- Production,Training <strong>and</strong> Consultancy, Inc , Meenakshi Pareek<br />

(Morarka Foundation), Henry W. Short.

BE PART OF ThE SOLuTION!<br />

Apply for IFOAM membership online at<br />

www.ifoam.org<br />

PROuD TO BE PART!<br />

Nartrudee Nakornvacha<br />

General Manager Organic Agriculture Certification Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

- ACT<br />

I am proud to be member of IFOAM because IFOAM takes care of<br />

small holder interests. The Internal Control System developed<br />

by IFOAM has been internationally recognized <strong>and</strong> significantly<br />

improves small holders market access opportunities.<br />

bob Quinn<br />

President kamut International, uSA<br />

I appreciate the efforts of IFOAM to promote organic<br />

production throughout the world. Their work to keep the<br />

integrity of organic st<strong>and</strong>ards high worldwide <strong>and</strong> harmonize<br />

these st<strong>and</strong>ards with governments has greatly added to the<br />

success of the worldwide trade of organic goods. I can not say<br />

enough for the many years of dedication by hard working <strong>and</strong><br />

capable staff <strong>and</strong> volunteers. I have enjoyed my association<br />

with these people over the years <strong>and</strong> have appreciated the help<br />

<strong>and</strong> encouragement they have offered to me.<br />

kari Örjavik<br />

Grolink Partner, Sweden<br />

I am happy that IFOAM faces the challenges for the organic<br />

sector, be it climate change, GMOs or cooperation with<br />

governments <strong>and</strong> private sector. There is a lot ahead of us <strong>and</strong><br />

therefore IFOAM should be strengthened. I am proud to be part.<br />

Souleyman bassum<br />

Agrecol-Afrique, Senegal<br />

I am proud that IFOAM membership revised the Principles<br />

of Organic Agriculture in a unique, truly global stakeholder<br />

process. It is of daily use for us, since we have based the<br />

principles of our organization on the same. I am proud to be<br />

part of IFOAM.<br />

V<strong>and</strong>ana Shiva<br />

Navdanya President, India<br />

winner of the ’right Livelihood Award‘ in 1 3<br />

I am happy to be member of an organization who positions<br />

itself at the right spot to successfully protect Organic<br />

Agriculture against the threat caused by Genetically Modified<br />

Organisms.<br />

Ong kung wai<br />

world board member, Malaysia<br />

We are many different people <strong>and</strong> interests living in one World.<br />

I join IFOAM to learn, build <strong>and</strong> live together in a better future<br />

in line with the Principles of Organic Agriculture.<br />

Mwatima Juma<br />

world board member, Tanzania<br />

IFOAM st<strong>and</strong>s for dialogue, harmonization <strong>and</strong> equivalence in<br />

the organic sector. This is why I engage myself in the IFOAM<br />

World Board.<br />

urs Niggli<br />

Fibl, Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

I cannot imagine another organization than IFOAM to represent<br />

Organic Agriculture globally. I am proud to be part.<br />

Volkert Engelsman<br />

Eosta, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

I am happy that IFOAM defends the holistic organic concept<br />

by defining the Principles of OA. To find the balance between<br />

ecological, social <strong>and</strong> economic objectives is crucial for my<br />

business. I am proud to be part.<br />

IFOAM – News<br />

13

Feature Interview<br />

Organic Farmer <strong>and</strong><br />

uS Senator Jon Tester<br />

Shares his Views with<br />

the Organic Movement<br />

Interview by Neil Sorensen<br />

In November 2006, organic<br />

farmer Jon Tester was elected<br />

to the United States Senate.<br />

Having an organic farmer<br />

in such a position of power<br />

represents an important<br />

opportunity for the entire<br />

international organic<br />

community. Tester c<strong>and</strong>idly<br />

shares his experiences <strong>and</strong><br />

world view in a telephone<br />

interview.<br />

FiBL – Professional Competence<br />

for Organic Agriculture Worldwide<br />

Research Institute of Organic Agriculture<br />

Forschungsinstitut für biologischen L<strong>and</strong>bau<br />

Institut de recherche de l’agriculture biologique<br />

Istituto di ricerche dell’agricoltura biologica<br />

Instituto de investigaciones para la agricultura orgánica<br />

How did you <strong>and</strong> your wife Sharla get involved in organic<br />

farming?<br />

It was in about ‘86 or so. There were a number of things that<br />

happened. We’re not exactly the biggest outfit out here, <strong>and</strong><br />

as we as we looked out the door, you’d see a lot of places that<br />

weren’t lived in, a lot of people that were leaving agriculture.<br />

They weren’t necessarily bad business people, but it just wasn’t<br />

financially sustainable. As the next ones on the block, we felt<br />

like we had to make some changes in our operation from a<br />

financial st<strong>and</strong>point. We never did get along with the seed<br />

treatments or the weed sprays very well, <strong>and</strong> to be honest<br />

we probably didn’t h<strong>and</strong>le them like they should have been<br />

Research <strong>and</strong> Development<br />

Project <strong>and</strong> feasibility studies<br />

Training <strong>and</strong> advice<br />

Conversion planning<br />

Pilot <strong>and</strong> demonstration trials<br />

Support for import <strong>and</strong> label<br />

certification<br />

Set-up of inspection <strong>and</strong> certification<br />

programmes<br />

Market surveys, marketing concepts<br />

<strong>and</strong> organic produce sourcing<br />

FiBL Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, Ackerstrasse, Postfach, CH-5070 Frick, Phone +41 62 865 7272, Fax +41 62 865 7273, info.suisse@fibl.org<br />

FiBL Germany, Galvanistrasse 28, D-60486 Frankfurt, Phone +49 69 713 769 90, Fax +49 69 713 7699 9, info.deutschl<strong>and</strong>@fibl.org<br />

FiBL Austria, Theresianumgasse 11/1, A-1040 Vienna, Phone +43 1 907 6313, Fax +43 1 403 7050 191, info.oesterreich@fibl.org www.fibl.org<br />

14 Feature Interview <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006

h<strong>and</strong>led. Combined with that fact, one day we met<br />

a woman who was working at Eden Foods that<br />

happened by. She was out at Quinn’s (Bob Quinn of<br />

Kamut International) place, <strong>and</strong> she said that if you<br />

convert your farm to organics, that there’s certainly<br />

a market for your grain. Since she worked at Eden,<br />

she said they would purchase the grain from us if it<br />

met quality st<strong>and</strong>ards for protein <strong>and</strong> so forth. The<br />

impetus for moving to organic was a combination<br />

of those things. We were truly Neophytes in the<br />

business, <strong>and</strong> the more we got into it, the more we<br />

liked it, <strong>and</strong> the more we liked being able to sell our<br />

products. The thing that really sold it for us (<strong>and</strong> we<br />

were certified by the OCIA at that point in time),<br />

when I went to an international organic meeting<br />

my first year. Nobody else around wanted to go to<br />

Philadelphia to that international meeting, so I did.<br />

During the meeting, the woman who we had sold<br />

the Durham (wheat) to (<strong>and</strong> it was a semi load, not<br />

a huge amount) came up to me <strong>and</strong> said ‘that was<br />

the best Durham we’d ever got.’ In retrospect, it may<br />

have been baloney, but it made me feel good about<br />

the product, because nobody had ever told me that<br />

what I was raising was good. You know, I’d take it<br />

to the elevator <strong>and</strong> they’d tell me what was wrong<br />

with it <strong>and</strong> they’d deduct me for this or deduct me<br />

for that. That was first time I actually sold grain<br />

to somebody who came up to me <strong>and</strong> said thanks<br />

for doing what you’re doing. That combination of<br />

things brought us to a level where we thought it was<br />

important to convert, <strong>and</strong> within five years we had<br />

the whole place converted, <strong>and</strong> it’s worked out very<br />

well for us.<br />

As an organization, IFOAM really believes in<br />

highlighting the role of women in Organic<br />

Agriculture. What kind of role has Sharla played in<br />

the development of your farm?<br />

This is a family farm. It’s been in the family since my<br />

gr<strong>and</strong>parents homesteaded it back in 1916. Just by<br />

definition, a family farm means exactly that. Just<br />

as my gr<strong>and</strong>mother did with my gr<strong>and</strong>father, they<br />

farmed side by side, <strong>and</strong> so did my mother <strong>and</strong> my<br />

father. Even though I was born 14 years after my<br />

gr<strong>and</strong>parents left the place <strong>and</strong> moved to town, I<br />

grew up with my parents <strong>and</strong> saw the role that my<br />

mother played in the operation of the farm. Whether<br />

it was helping to do the books <strong>and</strong> paying the bills<br />

or being a tractor driver, truck driver or combining<br />

at harvest time, she was there. It’s the same with<br />

my wife now. Particularly with this campaign, I<br />

was required to be on the phone a fair amount of<br />

time, <strong>and</strong> Sharla spent a fair amount of time on the<br />

combine, which is a job that I normally do. Typically<br />

she drives trucks at harvest time, <strong>and</strong> at seed time<br />

she’s moving trucks around, making sure I’ve got<br />

seed when I need it <strong>and</strong> helping to fill the drills. If<br />

something else is happening when I’m needed at<br />

the house, she’s out there taking care of business.<br />

It’s a family farm. The same thing can be said about<br />

my kids: they help to make up the interchangeable<br />

pieces that are part of what makes it a family farm.<br />

As with my gr<strong>and</strong>parents <strong>and</strong> with my folks, it’s been<br />

Feature Interview<br />

1

a joint operation since we moved out here in 1978.<br />

It’s just the way it is. There’s darn few things that I<br />

do that my wife can’t do, <strong>and</strong> I can’t say that about<br />

me, because there’s things she does that I flat can’t<br />

do. It’s part of what I consider to be the definition<br />

of a family farm, which is that partners move the<br />

operation forward together. When we made the<br />

conversion to organics, we sat down <strong>and</strong> talked<br />

about it. When we sell the grain or lentils or peas or<br />

whatever, we talk about it. Is this the right thing to<br />

be doing, selling to this person or that person, or is<br />

this price adequate to pay the bills? It’s a joint effort.<br />

What is the importance of having organic farming<br />

become more institutionalized in the Farm Bill,<br />

<strong>and</strong> do you have any specific plans in that regard?<br />

I think that where we’re at in Organic Agriculture<br />

is just to make that the Farm Bill includes the<br />

flexibility to let people farm organically. On a<br />

personal basis, I just hope we can encourage the kind<br />

of markets in conventional agriculture that we have<br />

in Organic Agriculture, <strong>and</strong> I hope we can maintain<br />

the kind of markets <strong>and</strong> improve upon them so we<br />

have competition in the marketplace. I think that<br />

it is critically important for the Farm Bill from the<br />

conventional <strong>and</strong> the organic st<strong>and</strong>point. Ultimately,<br />

I want a farm program that helps encourage financial<br />

sustainability that increases long-term competition<br />

in the marketplace. All of these elements apply<br />

to both conventional <strong>and</strong> Organic Agriculture . I<br />

want a farm program that really focuses on energy<br />

policy for this country that will help it achieve<br />

energy independence. I think we have tremendous<br />

opportunity in renewables here in the United States,<br />

which helps agriculture across the board, organic <strong>and</strong><br />

conventional. Traditionally, people in production<br />

agriculture have gotten there money from the<br />

marketplace. I want to keep it that way in organics<br />

<strong>and</strong> encourage it in conventional agriculture, too.<br />

How do you feel about the dumping of US products<br />

due to subsidies on developing countries?<br />

Well, I think we need to have trade agreements<br />

that work for people here in the United States <strong>and</strong><br />

for our trading partners abroad. Subsidies are an<br />

interesting argument, because there are different<br />

levels of subsidies all over the world, <strong>and</strong> they<br />

come in all different forms . Some are actual cash<br />

payments, others are subsidies to transportation<br />

industries, <strong>and</strong> the savings are passed on to people in<br />

agriculture. Here’s my focus is that we have to have<br />

trade agreements that work. You can’t be driving<br />

your trading partners’ people into poverty; that’s<br />

not a good trade agreement. But by the same token,<br />

trade agreements shouldn’t drive your own people<br />

into poverty or out of business <strong>and</strong> into bankruptcy<br />

either. You need to make sure you’re looking at both<br />

sides of the equation. Quite frankly, a lot of these<br />

trade agreements right now help out the selected<br />

few. I don’t think they’re in production agriculture,<br />

<strong>and</strong> they’re probably not in developing countries<br />

either. In the end, what needs to be protected,<br />

preserved <strong>and</strong> enhanced in this country is family<br />

farm agriculture. I think it’s critically important from<br />

a United States st<strong>and</strong>point for food security <strong>and</strong><br />

food availability throughout the world. When our<br />

agricultural base starts becoming more corporatized,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it’s becoming that way more <strong>and</strong> more, I think<br />

that’s a risky situation both economically <strong>and</strong> from<br />

the perspective of food security. There are subsidies<br />

all over the place. I know what it costs to raise a<br />

bushel of grain <strong>and</strong> a lentil. I can tell you if there<br />

weren’t subsidies right now (because there’s no<br />

competition in the marketplace), that there would be<br />

a mass exodus from the l<strong>and</strong>. It’s a two-sided coin. I<br />

hate subsidies with a passion. I’d love to have all our<br />

income come from the marketplace. I think that if<br />

there’s good competition in the marketplace it could<br />

be that way. You know as well as I do that there’s<br />

too much monopolization in the food industry right<br />

now, as with a lot of other industries.<br />

There’s been a lot of criticism throughout<br />

the world about organic products from China<br />

<strong>and</strong> some developing countries, entering the<br />

marketplace, it being suggested that there are not<br />

adequate controls. How do you feel about that?<br />

I’ve never been to mainl<strong>and</strong> China. I don’t know<br />

the challenges that they face. I know that they are<br />

many, but I do feel strongly in strong st<strong>and</strong>ards that<br />

are verifiable <strong>and</strong> transparent. If the transparency<br />

isn’t there, I don’t think the certification should<br />

take place. There are games that can be played <strong>and</strong><br />

1 Feature Interview <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006

games that have been played with certification over<br />

the years, <strong>and</strong> that’s one of the challenges that we<br />

have in the organic industry, where peer-review is so<br />

important. If there’s not peer-review to help with the<br />

transparency, then it puts our whole industry at risk.<br />

I can’t tell you if it has a high probability of being<br />

bogus, because I haven’t been there <strong>and</strong> I don’t know,<br />

I do know that if the inspection <strong>and</strong> certification<br />

process is not open, transparent <strong>and</strong> meets the<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards, then it has to change.<br />

How do you feel credibility can best be maintained<br />

through organic certification?<br />

I think you have to maintain the st<strong>and</strong>ards. You can’t<br />

have any erosion of st<strong>and</strong>ards that are significant.<br />

There’s always going to be some changes to<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards, but ultimately we have to adhere to that<br />

grassroots vision for organics that was there 30 years<br />

ago. If you improve the inspection, you improve the<br />

product through the number of eyes that watch the<br />

process, <strong>and</strong> I’ll give you an example. When we first<br />

started organics <strong>and</strong> made the conversion, we found<br />

that there needs to be more eyes on the conversion<br />

process, especially because of parallel production.<br />

Quite frankly, I’ve got some ideas about parallel<br />

production that a lot of people in the industry<br />

wouldn’t like. I don’t think it’s the right thing to<br />

be doing in organics, because it opens the door for<br />

problems. When we started the conversion, we had<br />

tours of the farm, <strong>and</strong> everybody we sold grain to<br />

came out <strong>and</strong> took a look around. Of course we had<br />

the inspection process, which I think helps ensure<br />

the quality of the product, but I also think that<br />

people who buy products from farms need to make a<br />

concerted effort to get out to those farms <strong>and</strong> take a<br />

look around. As a farmer in production agriculture,<br />

I’m always honored when somebody who’s buying<br />

my product comes to see what we have going on. I<br />

think that helps along with traditional inspections<br />

<strong>and</strong> audit trails. It’s been a little more difficult since<br />

I’ve been in the Montana Senate for eight years, but<br />

we always used to get together with neighbors once<br />

a month <strong>and</strong> visit about our successes <strong>and</strong> defeats,<br />

<strong>and</strong> talk about organic production. I think all that<br />

helps, getting together <strong>and</strong> talking about challenges<br />

we face <strong>and</strong> how we can meet those challenges. All<br />

those things go together. I think to have a good<br />

organic system, farmers need to feel like they’re in<br />

partnership with the processor, <strong>and</strong> they both need<br />

to feel like they’re in partnership with the consumer.<br />

How do you feel about the entrance of organic<br />

discounters <strong>and</strong> big corporations onto the scene?<br />

It’s a two-edged sword. Anytime you open up the<br />

market to have organics be more accessible to more<br />

people, that’s a positive. I think that if they’re getting<br />

into it for cheap food, to cheapen up the process, to<br />

cheapen the st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> to cheapen the products -<br />

if it’s all about cheap - I think it’s the wrong business.<br />

What enticed me into organics is food quality, soil<br />

health <strong>and</strong> improving the environment that our<br />

next generation has to do business in. Those are the<br />

important things, <strong>and</strong> there’s a cost to doing that.<br />

You can’t do that kind of stuff on the cheap.<br />

The cost of course to doing that is that you give up<br />

some things when those become the most important<br />

thing. If massive production becomes your most<br />

important driver, then you can do a lot of things on<br />

the cheap. The retailers that are out there putting<br />

more organic food out for the consumers, I think<br />

Feature Interview<br />

1

that’s a positive thing. I think anytime you can bring<br />

more organic consumers into the marketplace, that’s<br />

positive. In the end, if the goal is to cheapen the<br />

process, I think that’s something to be leery of.<br />

I know that you really care about the integrity of<br />

the soil <strong>and</strong> that you are into using green manures.<br />

How do you feel about soil as a living organism,<br />

just to get your underst<strong>and</strong>ing of ecology?<br />

I’m going to make a correlation here – it’s the basis<br />

by which I make a living. If I don’t have good soil<br />

health, if I’m not continually working to improve<br />

the health of my soil, it diminishes my ability to be<br />

successful in organics tremendously. I’ll tell you we<br />

went through some serious droughts here, over the<br />

last six or seven years. This last year wasn’t bad at all,<br />

but before that in 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2002, it was miserably<br />

dry here. My soil health tanked. There were things<br />

that happened from an ecological st<strong>and</strong>point that<br />

drove me crazy. I just couldn’t get anything to grow<br />

because we didn’t have any moisture. If I don’t have<br />

good soil health or if I see my soil health going in<br />

a negative fashion, it just absolutely takes away<br />

my ability to raise a product that’s a good quality,<br />

healthy product. What we do as farmers is manage<br />

soil. If we do a good job of managing soil <strong>and</strong><br />

Mother Nature rains on us, we’ll cut a hell of a crop,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it’ll be a good crop, a high quality crop. If we do<br />

a poor job of managing the soil, no matter how much<br />

it rains, we’re not going to raise a good crop. Soil<br />

management is critical, <strong>and</strong> that’s why I feel very,<br />

very strongly about a soil-building program being a<br />

critical part of a rotation. If you’re not continually<br />

trying to build your soil, you’re not going to succeed<br />

in Organic Agriculture over the long run. You will<br />

over the short haul, possibly, but not over the long<br />

1 Feature Interview <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006<br />

haul.<br />

How do you feel about the USDA deregulation<br />

of the genetically engineered (GE) rice known<br />

as Liberty Link (LL) 601 by the USDA that has<br />

contaminated rice supplies throughout the US <strong>and</strong><br />

the lawsuit by rice farmers?<br />

I’ve always gone by the theory that the customer is<br />

always right. If the customer doesn’t want GMO rice,<br />

we ought not to be forcing it on them. Anytime you<br />

have decisions by the government where they don’t<br />

take into consideration what the customer wants,<br />

they’re forcing people in production agriculture into<br />

a financial situation they don’t deserve <strong>and</strong> you need<br />

to take a look at the policy makers <strong>and</strong> change them.<br />

Do you have anything else you’d like to share with<br />

global organic sector?<br />

All I want to say is that I’m in an interesting<br />

situation. I’ve been in the organic trade for almost<br />

20 years. Before that we were conventional, <strong>and</strong> my<br />

farmer <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>father were good farmers. They<br />

were conventional farmers. The only reason I bring<br />

that up is because there’s a lot of good farmers out<br />

there. There’s a lot of good people that share the<br />

same vision for agriculture as some of the people in<br />

organics. Just because you’re into organic doesn’t<br />

mean you’re better than anyone else. There are<br />

some people in organics that might not have the

same vision for healthy soils <strong>and</strong> all that stuff that other people<br />

have. I don’t mean to get myself in a bind when I say this, <strong>and</strong><br />

I don’t want to point any fingers, because when you point one<br />

there’s always three pointing back at you. The truth is that I’m in<br />

a situation now where organics has done a lot of good things for<br />

production agriculture <strong>and</strong> consumers as well, <strong>and</strong> connecting<br />

consumers with people on the l<strong>and</strong> is always important. If I<br />

were going to say one thing from a more global view, I hope we<br />

can keep the kind of competition in the marketplace that we’ve<br />

had, because it’s what sets us aside. I hope we don’t see the kind<br />

of consolidation that’s happened in conventional agriculture in<br />

Organic Agriculture. Then on the other side of the coin, I’d like<br />

to see more competition in the conventional marketplace. From<br />

a marketplace st<strong>and</strong>point, if we look at where organics was <strong>and</strong><br />

where they are, we need to ensure that competition levels stay<br />

there. That’s something that very much worries me, because at<br />

the point <strong>and</strong> time the markets become consolidated in Organic<br />

Agriculture <strong>and</strong> we don’t have competition, I think it puts us in a<br />

real bind. That’s about all. That’s just kind of a personal concern<br />

that I have.<br />

interview By neil SOrenSen<br />

international Federation oF organic agriculture movements (iFoam)<br />

charlES-DE-gaullE-Str. 5, 53113 bonn, gErmany<br />

email: n.sorensen@iFoam.org<br />

Go back to the<br />

Table of Contents ><br />

Feature Interview<br />

1

Special Feature: Animals in Organic Production<br />

Fostering Organic<br />

Livestock Research–<br />

Priorities <strong>and</strong><br />

Preferences<br />

by Jim Riddle<br />

In the United States, it has<br />

only been legal to label meat<br />

as “organic” since February<br />

1999. Because of this, the<br />

organic livestock industry is still<br />

very much in its infancy, but<br />

production is growing rapidly.<br />

Now the Organic Outreach<br />

Coordinator at the University of<br />

Minnesota, Jim Riddle evaluates<br />

strategies for fostering organic<br />

livestock research.<br />

Jim Riddle giving his keynote speech at the 1st IFOAM International Conference on Animals in<br />

Organic Production.<br />

The Growing Organic Livestock Industry<br />

Certified organic pasture <strong>and</strong> rangel<strong>and</strong> more than doubled<br />

between 1997 <strong>and</strong> 2001, <strong>and</strong> was up 28 percent from 2000 to<br />

2001, mirroring the rapid expansion in organic livestock <strong>and</strong><br />

poultry. The number of certified organic beef cattle, milk cows,<br />

hogs, pigs, sheep, <strong>and</strong> lambs was up nearly four-fold since 1997,<br />

<strong>and</strong> up 27 percent from 2000 to 2001. Poultry animals raised<br />

under certified organic management – including laying hens,<br />

broilers, <strong>and</strong> turkeys – showed even higher rates of growth<br />

during this period. With the Organic Foods Production Act<br />

now in force, <strong>and</strong> with consumer dem<strong>and</strong> for organic products<br />

growing at over 20 percent per year, exp<strong>and</strong>ed research is<br />

needed to support livestock producers who choose to enter this<br />

growing sector.<br />

20 Special Feature: Animals in Organic Production <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006

Survey of Organic Livestock Research Needs<br />

During May <strong>and</strong> June 2003, the author constructed<br />

a list of potential topics to include in a survey of<br />

organic livestock research needs. The topics were<br />

selected based on the author’s experience as an<br />

organic producer <strong>and</strong> inspector. In addition, topics<br />

were selected from the Organic <strong>Farming</strong> Research<br />

Foundation’s (OFRF) annual survey of organic<br />

farmers <strong>and</strong> ranchers; the final report of the<br />

Network for Animal Health <strong>and</strong> Welfare in Organic<br />

Agriculture, a European Union funded Concerted<br />

Action Network; a list of research topics submitted<br />

by Ron Rosmann, Rosmann Family Farms,<br />

Harlan, IA; a list of Critical Needs for Extension<br />

Identified at Organic Inservice compiled by Penn<br />

State University; <strong>and</strong> a report entitled “Health<br />

<strong>and</strong> Welfare in Organic Livestock Systems” by Dr.<br />

Michael Meredith, Sunflower-Health, UK.<br />

The author compiled a draft list of research topics.<br />

The list was circulated via email discussion groups<br />

frequented by organic inspectors, certifiers,<br />

researchers, <strong>and</strong> producers. Comments were<br />

solicited. In July 2003, comments were incorporated<br />

to construct the final survey questionnaire.<br />

Organizers posted the survey of organic livestock<br />

research needs on the website of the University<br />

of Minnesota based Minnesota Institute for<br />

Sustainable Agriculture (www.misa.umn.edu)<br />

in August <strong>and</strong> September 2003. The survey was<br />

conducted to help the University of Minnesota <strong>and</strong><br />

other research institutions meet the needs of the<br />

organic livestock industry.<br />

Respondents prioritized organic livestock research<br />

topics in ten categories. Respondents were also<br />

invited to submit research ideas of their own. Notice<br />

of the survey was circulated throughout the U of<br />

MN system, <strong>and</strong> to organic certification agencies,<br />

organic producer groups, organic inspectors, <strong>and</strong><br />

sustainable agriculture e-mail discussion groups.<br />

In addition, one organic dairy company printed the<br />

survey <strong>and</strong> mailed it to its producers.<br />

Respondents were asked to provide information<br />

on their places of residence <strong>and</strong> occupations.<br />

Respondents were asked to indicate if they were<br />

crop farmers, organic crop farmers, livestock<br />

producers, organic livestock producers, researchers,<br />

certifiers, inspectors, or other. Respondents were<br />

not limited to choosing one occupation.<br />

Participants<br />

A total of 203 people completed the survey.<br />

Minnesota had the highest number of respondents<br />

at 32. New York was second with 24. There<br />

were 22 from Wisconsin; 15 from Iowa; 11 from<br />

Pennsylvania; 9 each from Illinois <strong>and</strong> Washington;<br />

8 from Canada; 7 from Wyoming; <strong>and</strong> 5 each from<br />

California <strong>and</strong> Vermont. Seventy-four respondents<br />

indicated that they were organic livestock producers.<br />

There were 39 organic crop farmers, 35 livestock<br />

producers, 32 researchers, 13 inspectors, 12<br />

certifiers, 5 crop farmers, <strong>and</strong> 57 who selected other.<br />

Method of Analysis<br />

Respondents were asked to review the list of<br />

research topics <strong>and</strong> indicate the level of priority that<br />

should be assigned to each topic, on a scale of 1 to<br />

5, with 1 being the lowest <strong>and</strong> 5 being the highest.<br />

Mean scores for each topic were calculated by adding<br />

all scores <strong>and</strong> dividing by the number of responses<br />

for that topic. Median (the middle score of an<br />

Special Feature: Animals in Organic Production<br />

21

ordered list of scores) <strong>and</strong> mode scores (the most<br />

frequent score) were also calculated for each topic,<br />

using the PROC UNIVARIATE procedure of SAS.<br />

An index was calculated for each topic to take into<br />

account the mean, median, <strong>and</strong> mode scores as<br />

well as the number of responses for the topic; as<br />

follows: Index = (mean + median + mode) * (number<br />

of responses / 203). 203 is the total number of<br />

submitted surveys. Thus, the index accounts for<br />

Top Twenty Topics<br />

both the willingness of survey respondents to spend<br />

time scoring a given survey topic, as well as the<br />

relative approval of it as a research topic by those<br />

who chose to answer.<br />

The topics were ranked using the index score,<br />

both within the ten broad categories <strong>and</strong> across all<br />

categories. The ranking across all categories was<br />

then used to find the “Top Twenty” research topics.<br />

Because the number of responses to a topic was part<br />

The following topics were ranked, according to index scores, as the highest priorities for organic livestock research<br />

by survey respondents:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Catalog animal health problems for various species, listing approved health care options <strong>and</strong> allowed<br />

medications.<br />

Analyze the nutritional <strong>and</strong> health value of organically produced livestock products, especially pasture raised<br />

or grass fed livestock.<br />

Explore impacts of “systems” approach (rotational grazing, multi-species grazing, etc.) on internal <strong>and</strong> external<br />

parasite loads for various species.<br />

Organic methods of building soil fertility to optimize livestock health <strong>and</strong> thereby reduce or eliminate the need<br />

for medications, vaccines, parasiticides, <strong>and</strong> supplemental vitamins <strong>and</strong> minerals.<br />

Organic Best Management Practices (OBMPs) for least-toxic parasite management for various species.<br />

OBMPs for prevention <strong>and</strong> treatment of mastitis.<br />

Examine naturally occurring sources of vitamins <strong>and</strong> minerals within organic feed compared to use of<br />

supplementation materials.<br />

Analysis of distribution channels used for organic livestock products <strong>and</strong> recommendations for improved<br />

processing, h<strong>and</strong>ling, <strong>and</strong> distribution systems.<br />

Manure management systems which do not contaminate crops, soil, or water with plant nutrients, heavy<br />

metals, or pathogenic organisms <strong>and</strong> which optimize recycling of nutrients.<br />

Livestock record keeping systems for sound management, profitability, <strong>and</strong> organic certification compliance.<br />

Comparison of investments needed, rate of return, <strong>and</strong> profitability of organic <strong>and</strong> non-organic livestock<br />

systems.<br />

Study impacts of organic livestock operations on local <strong>and</strong> regional economic development<br />

Analyze how livestock production impacts the entire diversified organic farm, including impacts on fertility<br />

management; weed, pest, <strong>and</strong> disease pressure; utilization of resources; water quality; farm labor; <strong>and</strong><br />

profitability.<br />

Market survey of supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> for organic meat products in the Upper Midwest.<br />

Breeds of various species best suited to organic production – feed utilization, grazing response, disease <strong>and</strong><br />

parasite resistance, ease of reproduction, <strong>and</strong> minimization of stress.<br />

Nutritional value of weeds, how they can best be utilized in livestock diets, <strong>and</strong> threshold levels for inclusion<br />

in livestock rations.<br />

Comparison of grain-based organic livestock systems with grass-based organic systems. OBMPs for least-toxic<br />

fly control.<br />

Examine holistic strategies, including: 1) augmentation or introduction of predators or parasites; 2) development<br />

of habitat for natural enemies; 3) non-synthetic controls such as lures, traps, <strong>and</strong> repellents; 4) manure<br />

management systems; 5) pasture rotation; 6) use of clean, dry bedding; <strong>and</strong> 7) impact of moisture control.<br />

OBMPs for the prevention of various diseases in various livestock species <strong>and</strong> breeds.<br />

22 Special Feature: Animals in Organic Production <strong>Ecology</strong> & <strong>Farming</strong> | SEptEmbEr - DEcEmbEr 2006

of the index score, it tended to weigh against topics<br />

from “minor” species such as goats/sheep <strong>and</strong> bees<br />

appearing in the Top Twenty. Those with an interest<br />

in these categories can check the ranking of topics<br />

within the categories.<br />

Research Needs Identified<br />