artenol0416_sm_flipbook

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FALL 2016<br />

DAVID PRYCE-JONES<br />

Modern art?<br />

‘Bogusness!’<br />

WALKER MIMMS<br />

Boswell seeks,<br />

finds self<br />

Make art great again<br />

Alex Melamid’s challenge:<br />

Want to save art? Destroy it<br />

$10.00 US/CAN

g a l l e r y<br />

VOHN GALLERY serves as a platform for exhibitions,<br />

intellectual inquiry and cultural exploration. Though<br />

its name is new, the gallery is a continuation of a<br />

journey that was started in 2008.<br />

The group of international artists that VOHN works<br />

with share a strong conceptual underpinning to<br />

their practices. Their work is in the collections of<br />

MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum and The Guggenheim<br />

Museum. VOHN’s projects/exhibitions have<br />

received critical response in The New York Times,<br />

The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal and Interview<br />

Magazine, among others.<br />

VOHN GALLERY launched in September 2014 as a<br />

re-imagining of a project space that ran from 2012<br />

to 2013 in Chelsea, New York. The new gallery’s program<br />

will include upcoming exhibitions in TriBeCa, offsite<br />

projects and the sponsoring of Artenol magazine.<br />

vohngallery.com<br />

Further information: info@vohngallery.com

From the Editor<br />

4<br />

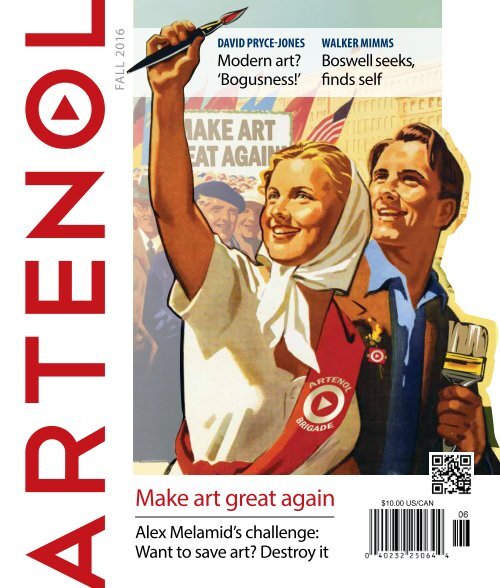

ON THE<br />

COVER<br />

The zeal is<br />

contagious as<br />

art workers take<br />

to the streets to<br />

celebrate art’s<br />

imminent return<br />

to greatness.<br />

Soviet-era<br />

poster<br />

repurposed<br />

for Artenol<br />

n WITH THE 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN IN THE FINAL THROES OF ITS YEAR-LONG ASSAULT<br />

ON OUR POLITICAL SENSIBILITIES, ARTENOL HAS DECIDED TO TAKE INSPIRATION FROM ONE<br />

of its ubiquitous slogans for this issue’s theme. No, it’s<br />

not “Lock her up!” We’ve devoted our Fall 2016 effort to<br />

the lofty goal expressed in the phrase,<br />

“Make art great again.” This, of course,<br />

begs the question: What is great art?<br />

Artenol founder Alex Melamid has a<br />

pretty good idea what isn’t great art. In<br />

a lecture given at the Kopkind Colony<br />

in Guilford, Vt., in July, Alex laid out<br />

the failings of contemporary art, as-<br />

David Dann<br />

serting that it's not the economy that is at the heart of<br />

our malaise, "It's the culture,stupid!" (more inspiration<br />

from the political realm). His words, and contributions<br />

from the Kopkind workshop participants, form this<br />

edition's cover story.<br />

Also contributing to the “make art great again”<br />

theme are four art world professionals. They share<br />

their observations as members of a vast collective that<br />

labors behind the scenes, providing support services to<br />

art institutions. Michelle Furyaka and her art consulting<br />

firm offer a strategic plan for restoring greatness<br />

to art. Conservator Erica James profiles the role art<br />

conservation plays in the nefarious “Museum Value<br />

Machine.” Artenol's publisher, Gary Krimershmoys,<br />

discusses his transition from Wall Street broker to a<br />

socially-responsible investor in great art. And Rowling<br />

Dord chats with a museum “guard” who sees himself<br />

as an integral part of what makes great art great.<br />

In this issue you’ll also find entertaining – and<br />

provocative – stories by Josie Demuth and Julia Kissina,<br />

as well as diverting essays on fashion – both sartorial<br />

and gestural – by Stan Tymorek and Zinovy Zinik,<br />

Artenol’s British editor. Renowned author and editor<br />

David Pryce-Jones offers an insightful asses<strong>sm</strong>ent of<br />

moderni<strong>sm</strong>’s short selling of humanity.<br />

On our display pages, you’ll find a dramatic image<br />

taken of the aftermath of a fire by news photographer<br />

Chris Ramirez, and an uncanny recreation in three dimensions<br />

of a familiar Pop Art image by food stylist<br />

Laurie Knoop.<br />

This issue of Artenol was made possible by these creative<br />

contributors, and I'm grateful to them for their<br />

generosity. The magazine’s editorial, production and<br />

support staff were tireless in their efforts to bring Fall<br />

2016 to newsstands. But its publication was also greatly<br />

aided by the many supporters who donated to the<br />

magazine’s recent Kickstarter campaign.<br />

In just under 30 days, we were able to raise $8,251,<br />

an amount well in excess of our stated goal of $7,500.<br />

Those funds will go toward expanding our distribution<br />

and developing our Web presence as we move<br />

into our second year of publication. Response to the<br />

campaign was greatly encouraging to all of us here in<br />

Artenol’s corporate headquarters, and we are determined<br />

to move the magazine forward with more insightful<br />

articles, provocative essays, absurdist humor,<br />

subtle satire and whatever else we can think of to help<br />

“make art great again.”<br />

Thanks to all who helped out, and remember: It's the<br />

culture, stupid!<br />

n<br />

FALL 2016

Inside<br />

9 The human dimension<br />

Moderni<strong>sm</strong> plays games with us by David Pryce-Jones<br />

14 Make art great again: The contractor<br />

A research firm’s program for MoMA by Michelle Furyaka<br />

16 Make art great again: The conservator<br />

Serving the “Museum Value Machine” by Erica James<br />

20 Make art great again: The investor<br />

The art of socially-engaged investing by Gary Krimershmoys<br />

22 Make art great again: The artworker<br />

A “guard” contributes to art’s greatness by Rowling Dord<br />

24 Starting over: Rethinking art<br />

An art workshop at the Kopkind Colony by Alex Melamid<br />

37 Snap, crackle and pop art<br />

Painting re-creation takes the cakes by Laurie Knoop<br />

42 Scene: Fire call<br />

A barn fire caught by a firefighter’s camera by Chris Ramirez<br />

45 Fraught couture<br />

When royal dressing was a royal pain by Stan Tymorek<br />

50 Poem: Fire or water<br />

Inspiration from the flow of Goya’s art by Gabe Seidler<br />

52 Good heaven! What is Boswell?<br />

Examining “The Biographer’s” early years by Walker Mimms<br />

57 Story: We don’t give a shit ...<br />

Trendy art exhibit is a real killer by Julia Kissina<br />

33 The equal opportunist<br />

The secret to one artist’s success by Josie Demuth<br />

63 Closer: Full mental jacket<br />

Seen in the New York subway by Elisabeth Kaske<br />

Departments From the editor 4 | Letters 6 | Contact 7 | Contributors 8 | Find Artenol on the Web 61<br />

Hand job<br />

What hidden hands<br />

say about those<br />

who hide them<br />

Essay by Zinovy Zinik<br />

38<br />

OUT OF SIGHT

6<br />

Please send all<br />

correspondence to<br />

info@artenol.<br />

org. Letters<br />

may be edited<br />

for length<br />

and clarity.<br />

Letters<br />

Class act<br />

I just received my latest issue of Artenol, the “Money<br />

Issue,” and I love it. Last fall I used your premiere<br />

issue for my class at California College of the Arts<br />

in Oakland, Cal. It was a great way to start the year.<br />

With all that is going on in the world, I have decided<br />

to use the theme “The Color of Money” for my color<br />

theory class, and I think the “Money Issue” (Summer<br />

2016) would be a great way to kick-off the discussion.<br />

Could you please let me know if it is possible<br />

to order 18 copies for my students and if so, what<br />

would the cost be? Thank you. Keep on publishing!<br />

Eugene Rodriguez<br />

Via email<br />

August 6, 2016<br />

Editor: Prof. Rodriguez’s copies of Artenol were shipped<br />

soon after we received his request. We hope his students<br />

found the “Money Issue” inspiring. If you missed your<br />

copy, you can purchase one at artenol.org/subscribe.html.<br />

Art work<br />

I liked that Artenol devoted space to workers’<br />

rights, or lack of, along with Hedrick Smith’s look<br />

at what used to be called “robber-baron capitali<strong>sm</strong>”<br />

(“Hired? Check Your Rights ...,” “The Share Withholders,”<br />

Summer 2016). Missing from the issue, however,<br />

was any mention of labor unions. However flawed,<br />

unions are the one defense working people have to<br />

protect themselves. Since the “Reagan Revolution”<br />

unions have been under constant attack, with no<br />

help from the Democrats they supported. That is<br />

because union are, arguably, the best method to<br />

redistribute wealth in our nation; they created the<br />

home and car-owning “middle class” that has been<br />

disappearing. It is those people whose American<br />

Dream has been stolen who support the insurgent<br />

candidacies of Sanders and Trump.<br />

Well, you might ask, that might be true, but unions<br />

... art ...? And I say visit the Hospital Workers Local<br />

1199 hall in New York and check out the mosaic<br />

mural built around Frederick Douglass’s “Without<br />

struggle there is no progress.” Or the Benny Bufano<br />

mural at the ILWU Local 6 Hall in Oakland. Just to<br />

mention two I know well. Unions have promoted<br />

worker culture and art since before the Depression,<br />

with annual festivals in Washington and the Bay<br />

Area. When I was a union official we produced<br />

special edition union newsletters celebrating our<br />

worker-artists, writers, actors, singers. Labor educators,<br />

training generations of union leaders, routinely<br />

MURAL An allegorical work by artist Benny Bufano<br />

dominates one wall of the ILWU Hall 6 in Oakland, Cal.<br />

Photo provided<br />

include film and fiction, and teach hard-bitten shop<br />

stewards to write poetry. Here’s a haiku written by<br />

a Bay Area fast food worker that is life-changing; I<br />

gave them the first line:<br />

on the job today<br />

a customer yelled at me<br />

I spit in her food<br />

There have been hundreds, perhaps thousands, of<br />

working class artists who – like Artenol – reject crass<br />

commerciali<strong>sm</strong> and celebrate real people, who express<br />

their feelings through art. Yes, “It’s the culture,<br />

stupid,” including working class culture.<br />

Albert Lannon<br />

Retired Labor Educator, Laney College<br />

Former staff and local officer,<br />

International Longshore & Warehouse Union<br />

Via email<br />

August 7, 2016<br />

PayPal alternative<br />

I would like to subscribe to Artenol, but I don’t want<br />

to use PayPal. Is there another way I can pay for a<br />

subscription?<br />

Richard Helmick<br />

Via email<br />

August 4, 2016<br />

Editor: Yes. In the PayPal window that opens after you<br />

click “Subscribe,” there is link that says “Pay using your<br />

credit or debit card.” Click that and you should be able to<br />

use either of those alternatives. If you don’t see that link,<br />

you may need to change your browser privacy settings to<br />

allow “cookies” and other personal data transference.<br />

FALL 2016

FALL 2016 | ISSUE 6<br />

PUBLISHER<br />

MANAGING EDITOR/<br />

ART DIRECTOR<br />

ASSISTANT EDITOR<br />

BRITISH EDITOR<br />

ACCOUNTS/CIRCULATION<br />

SOCIAL MEDIA<br />

PUBLICITY/OUTREACH<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

FOUNDER<br />

LEGAL COUNSEL<br />

PUBLISHED BY<br />

ON THE WEB<br />

CONTACT US<br />

Gary Krimershmoys<br />

David Dann<br />

Walker Mimms<br />

Zinovy Zinik<br />

Denise Krimershmoys<br />

Z Nelson<br />

April Hunt<br />

David Zelikovsky<br />

Walker Mimms<br />

David Dann<br />

Alex Melamid<br />

Katya Yoffe, PLLC<br />

Art Healing Ministry<br />

Suite 8G<br />

350 West 42nd Street<br />

New York, NY 10036<br />

artenol.org<br />

facebook.com/Artenol<br />

instagram.com/artenol<br />

info@artenol.org<br />

Get into the spirit<br />

of New York.<br />

Artenol is published four times annually by the<br />

Art Healing Ministry, 350 West 42nd Street, Suite 8G,<br />

New York, NY 10036. © 2016 Art Healing Ministry.<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Fall 2016, Issue 6.<br />

Single issues of Artenol are $10; foreign orders are<br />

$22 per issue; a 1-year subscription (4 issues) is $39;<br />

foreign subscriptions are $79. For information on how<br />

to order issues, please go to artenol.org/subscribe.html.<br />

For customer service regarding subscriptions, please call<br />

845-292-1679. Reproduction of any part of this publication is<br />

prohibited without written permission from the publisher.<br />

All submissions become the property of Artenol unless otherwise<br />

specified by the publisher. Printed in China.<br />

Handcrafted,<br />

award-winning spirits<br />

Available at retailers throughout the tri-state area<br />

catskilldistilling.com<br />

7

8<br />

ATTORNEY ADVERTISING<br />

The Law Office of<br />

Katya Yoffe, PLLC<br />

International<br />

Business<br />

& Art Law<br />

77 Water Street, Suite 852<br />

New York, New York 10005<br />

646-450-2896<br />

katya@kyoffelaw.com<br />

kyoffelaw.com<br />

Rated by<br />

SuperLawyers<br />

for 2014, 2015<br />

Contributors<br />

• Josie Demuth | The Equal Opportunist (page 33)<br />

Josie Demuth is an author whose books include Liggers<br />

and Dreamers (2015) and The Guest (2012).<br />

• Michelle Furyaka | The Consultant (page 14)<br />

As president of FURY Art Advisory, Michelle Furyaka<br />

has helped art institutions around the world organize<br />

strategies for creating and expanding collections of art.<br />

• Erica James | The Conservator (page 16)<br />

Erica James is an art conservator in private parctice, providing<br />

painting conservation services for art institutions<br />

and individuals. She is also a poet and technical editor.<br />

• Julia Kissina | We Don’t Give a Shit ... (page 57)<br />

A member of the Russian Samizdat movement during<br />

the 1980s and ’90s, author and artist Julia Kissina is also<br />

the creator of The Dead Artist’s Society. Her books include<br />

Elephantina’s Moscow Years and Shadows Cast People.<br />

• Laurie Knoop | Snap, Crackle and Pop Art (page 37)<br />

Food stylist and producer Laurie Knoop owns Studio 129<br />

in New York City, where she styles food for photography<br />

and video for clients like Savory, Food and Wine, Culture<br />

Magazine, Simon and Schuster, and Harper Collins.<br />

• Gary Krimershmoys | The Investor (page 20)<br />

A provider of holistic wealth management services, with<br />

a focus on socially-responsible investing, Gary Krimershmoys<br />

worked for years in capital markets. He has also<br />

facilitated art exhibits and is the publisher of Artenol.<br />

• Alex Melamid | Rethinking Art (page 24)<br />

One half of the famed Russian art duo Komar and Melamid,<br />

Alex Melamid has continued to create art on his<br />

own since 2013. In 2015, he founded Artenol magazine.<br />

• Walker Mimms | Good Heaven! ... (page 52)<br />

Walker Mimms is a writer living in Nashville. He is also<br />

Artenol’s assistant editor.<br />

• David Pryce-Jones | The Human Dimension (page 9)<br />

David Pryce-Jones is a noted author and editor for<br />

National Review. His books include Betrayal: France, the<br />

Arabs, and the Jews (2006) and Fault Lines (2015).<br />

• Chris Ramirez | Scene (page 42)<br />

A freelance photographer and journalist for The New York<br />

Times, the Discovery Channel, The Wall Street Journal and<br />

others, Chris Ramirez is also a volunteer firefighter for a<br />

<strong>sm</strong>all community in upstate New York.<br />

• Stan Tymorek | Fraught Couture (page 45)<br />

Stan Tymorek is an author, copywriter and editor of<br />

several volumes of poetry for Abrams. He was formerly<br />

creative director for Lands’ End.<br />

• Zinovy Zinik | The Hidden Hand (page 38)<br />

A Moscow-born novelist and critic who lives in London,<br />

Zinovy Zinik is a regular contributor to The Times Literary<br />

Supplement and BBC radio, and is Artenol’s British editor.<br />

FALL 2016

Opener<br />

The human dimension<br />

By David Pryce-Jones<br />

My family shares a<br />

house in Florence, the city<br />

of the high art of the Italian<br />

Renaissance. To go into<br />

the museums and churches<br />

there is to be in touch with<br />

the Old Masters, and the<br />

experience has the effect<br />

of making you sense that<br />

there is more to life<br />

than you thought.<br />

And that, I take it, is the purpose of all art. Writing novels<br />

as I do, I have learned that no matter whether the theme<br />

is positive or negative, success depends on being able to<br />

create this mysterious sense inherent in good art that life<br />

would offer more if only you reached out for it.<br />

The Old Masters had an advantage: They were religious,<br />

or at least worked in an atmosphere of religious<br />

faith. Over a period of four or five hundred years, the<br />

core subject of painting was the fate of every human<br />

being after his or her death, either salvation or damnation.<br />

Angels and beauty on one side of the picture<br />

or fresco, demons and ugliness on the other side. Put<br />

another way, art used to be akin to worship, a paying<br />

of respects to whoever or whatever gave the artist his<br />

gifts. Like the huge majority of people today, I am an<br />

agnostic, which means a lot of hard work to find in<br />

today’s art the moral equivalent of faith.<br />

A great friend in Florence was Sidney Alexander,<br />

alas, no longer with us. A big man in every sense, also<br />

shambling and shambolic, he had fought in the U.S.<br />

infantry in Italy during the war, and stayed on afterwards<br />

on the scheme organized by Senator Fulbright<br />

to pay the university education of every ex-serviceman<br />

who wanted it. A man of the widest culture, Sidney<br />

played the flute and gave concerts, learned Latin in addition<br />

to Italian and created impeccable translations of<br />

the Odes of Horace and the classic work of the Renaissance<br />

historian Francesco Guicciardini that have both<br />

been published by a university press. He also wrote<br />

the biography of Marc Chagall. His special study,<br />

however, was Michelangelo, about whom he published<br />

several books. One day, he agreed to guide me<br />

on an explanatory tour of the works of Michelangelo<br />

that are to be seen around Florence. Standing in front<br />

of the famous statue of the young biblical David sizing<br />

up the shot that will kill Goliath, he quoted some lines<br />

from a poem by Michelangelo to the effect that a “Yes”<br />

and a “No” moved him equally. Sidney was saying<br />

that Michelangelo’s greatness lay in his understanding<br />

that the difference between the good and the bad is an<br />

issue for human beings, not God.<br />

In my mind’s eye, I still see Sidney turning to me<br />

CUBISM<br />

SQUARED<br />

Read Sidney<br />

Alexander’s poem,<br />

“Portrait of the<br />

Artist’s Child in<br />

a Predicament,”<br />

published in The<br />

New Yorker, at<br />

artenol.org<br />

9

to utter one of his deepest convictions: “Few things are<br />

more bogus than modern art.” The cause of this dereliction<br />

is the playing of games with everything that comprises<br />

the human being, the face and the body, the setting<br />

and the landscape. The artist is informing you that<br />

character and moral judgment are unimportant, and all<br />

you need know is how clever the artist himself is.<br />

It would make a good subject for a book to try to<br />

pinpoint why and how and when the arts all lost their<br />

human dimension: Painting went non-figurative, music<br />

forsook melody, poetry abandoned rhyme, architecture<br />

meant building machines for living, and so on. It’s a<br />

hundred years since the Dada movement reduced men<br />

and women to absurdity, which may perhaps have been<br />

a pacifist sneer of superiority to a world waging the First<br />

World War. I suspect that Picasso and Cubi<strong>sm</strong> have a<br />

lot to answer for, as well. Soviet realist art showed men<br />

and women as mere cogs in the machinery of Five Year<br />

Plans. At the same time, the art of the Old Masters has<br />

been effectively di<strong>sm</strong>issed as irrelevant. Anyone who<br />

might try to follow the great tradition would be mocked<br />

as a romantic, a dupe engaged in meaningless beautification,<br />

a grievous fault in the view of the politically<br />

correct. The world has become horrible and frightening,<br />

runs this line of thought, and art should therefore reflect<br />

it. The new does not succeed the old, but degrades<br />

and throttles it. Trying to invent organizing principles<br />

that would garner status in academia, critics confect<br />

whole categories and movements of uglification, such<br />

as Brutali<strong>sm</strong> or Minimali<strong>sm</strong>. Conceptual art is the outcome<br />

of the kindergarten teacher’s encouragement that<br />

everyone is an artist just because they say they are, and<br />

there’s no need for all that tiresome preparation.<br />

Not long ago, I found myself in Bilbao and took the<br />

risk of visiting the Guggenheim Museum there. Supposedly<br />

a showpiece of Modernist architecture designed<br />

by someone very famous and much applauded,<br />

the museum is an assemblage of irregular caverns in<br />

which you immediately become a disconsolate wanderer<br />

in search of order which is not there. Up on the<br />

third floor, as I recall, the caverns were more like warehouses<br />

in which were stacked huge and oddly shaped<br />

but overpowering red lumps, the work of someone else<br />

very famous and much applauded. Leaving this museum,<br />

you could only conclude that art and humanity<br />

are dead, laid out in a mortifying Kafkaesque setting.<br />

CAVERNOUS The Guggenheim Bilbao, universally acclaimed as one of<br />

the contemporary art world’s great museums, strikes some visitors as<br />

Moderni<strong>sm</strong> on a dehumanizing scale. Guggenheim Bilbao photo<br />

See a video about<br />

the Bilbao museum<br />

at artenol.org.<br />

10

The museum is an assemblage of<br />

irregular caverns in which you immediately<br />

become a disconsolate wanderer in search<br />

of order which is not there.<br />

The Royal Academy of Arts was once the protective<br />

haven of tradition that its name suggests. Here is the<br />

announcement of its forthcoming exhibition: “Abstract<br />

Expressioni<strong>sm</strong> will forever be associated with the restlessly<br />

inventive energy of 1950s New York. Artists like<br />

Pollock, Rothko and de Kooning broke from accepted<br />

conventions to unleash a new sense of confidence in<br />

modern painting. Experience the scale, color and energy<br />

of their radical creations in this the first major survey<br />

of the movement in the U.K. since 1957.”<br />

Abstract Expressioni<strong>sm</strong> is a phrase that would have<br />

sent my friend Sidney into a disquisition about bogusness.<br />

For a start, the two words have no genuine association<br />

and have been shunted together to give an<br />

appearance of scholarship. Far from being restlessly<br />

inventive, the three identified artists were dealing in<br />

splodges and stripes connected, if at all, to interior<br />

decoration rather than painting. A new sense of confidence<br />

implies an old lack of it, now being resolved.<br />

That phrase, and the co-opted nouns “scale, color and<br />

energy,” amount to a euphemistic way of concealing<br />

the role of the agents and dealers and collectors who<br />

have made a market in these painters, and buy and sell<br />

their canvases as ersatz stocks. The only thing that is<br />

radical is the sum of money put into speculations of<br />

the kind. I know one collector who spent a hundred<br />

thousand pounds on a picture so constructed that it<br />

would fall to pieces and disintegrate so that after ten<br />

years nothing would be left of it. To buy a picture in<br />

order to boast that money is no object to the purchaser<br />

goes way beyond ordinary bogusness.<br />

I conclude with a shaft of good news. There are two<br />

art schools in Florence engaged in counter-revolution,<br />

that is to say teaching technique as it was taught and<br />

practised in the time of the Old Masters. Graduating<br />

from these classes, students should be able to restore<br />

to art the human element and the moral judgment that<br />

goes with it. We will all be the better for it. n<br />

11

12<br />

FALL 2016

Artenol’s campaign<br />

to reinvigorate art<br />

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN

THE CONSULTANT<br />

With this issue of Artenol, we address the perplexing problem of contemporary art’s general banality.<br />

Time was when art played a central role in the lives of everyday people, but no longer. To rescue<br />

art from this malaise, to restore it to its former greatness, Artenol asked FURY Art Advisory, a leading<br />

research firm, to tackle the task of “making art great again.” We proposed that the company<br />

address the issue as though the Museum of Modern Art were its client. Michelle Furyaka, FURY’s president and<br />

CEO, and her team created this report, an analysis of the issue with suggestions for resolving it, as she would<br />

have done for any of FURY’s Fortune 500 clients. We believe it offers a fresh perspective on the issue. – Editor<br />

The Museum of Modern Art ( moma) is one<br />

of the largest and most influential museums in the<br />

world, housing more than 150,000 works of art as well<br />

as a film archive and an extensive library.<br />

It is evident that this museum is the world<br />

authority on modern art. Since 1929, when<br />

founded by Abigail “Abby” Rockefeller, the museum<br />

and its exhibitions have been captivating the public<br />

with legendary artists like Van Gogh and Picasso. It’s<br />

no wonder its early founders were called the “daring<br />

girls.” Today this renowned art institution is once<br />

By Michelle<br />

Furyaka<br />

again tasked with a “daring” assignment:<br />

to investigate and develop a well-defined<br />

strategy for “making art great again.”<br />

Proposal: FURY Art Advisory was selected<br />

based on their expertise in the art industry.<br />

As a potential partner, they will<br />

conduct a series of research initiatives<br />

and offer a solution on how to “make art<br />

great again.” Consulting firms are often brought in to<br />

conduct market research and present museums and<br />

non-profits with their findings. Analytical findings<br />

allow clients to understand exactly what is happening<br />

in the marketplace, thus enabling them to make<br />

decisions based on that data.<br />

FURY will analyze<br />

the musuem’s<br />

assets and identify<br />

qualifications that<br />

make artists ‘great.’<br />

developing superior strategies, the MoMA chooses<br />

FURY as a strategic partner.<br />

Solution: To help MoMA tackle distracting forces and<br />

misinterpretations worldwide, FURY will provide<br />

a comprehensive offering from its suite of integrated<br />

solutions. This includes a review of the history of<br />

the museum and the original pioneering spirit of its<br />

founders. Market conditions for artists and collectors<br />

are far better today than in the days following the<br />

Great Depression when the museum first opened.<br />

Therefore, FURY will evaluate current<br />

market conditions and present studies on<br />

qualifying artists, based on various technical<br />

and functional skill sets. They will<br />

also provide an analysis of public opinion<br />

and awareness, as well as a forecast of<br />

collector trends and reliable investments.<br />

FURY will conduct an extensive study of<br />

other art institutions and will arrive at a<br />

specific roadmap for “making art great again.” FURY<br />

will also test various focus groups and will perform<br />

a root-cause analysis to identify issues and obstacles.<br />

Findings will be shared, viable solutions will be proposed<br />

and a viable roadmap will be selected and implemented.<br />

14<br />

Business challenge: MoMA wants to “make art great<br />

again,” but is challenged with the presence of various<br />

distractions in the market and various market<br />

barriers. Many people are dissatisfied with the direction<br />

art has taken. MoMA needs real-time insights<br />

into the current art market and a clear analysis of<br />

the public’s perception. It is also extremely important<br />

to build a strong awareness and attract followers<br />

to this initiative. The museum wants to explore the<br />

option of starting a movement, an art collective that<br />

would “make art great again.” Recognizing FURY’s<br />

deep knowledge of the art market and its expertise in<br />

Strategy: During the discovery phase of the project,<br />

FURY will endeavor to understand and gather information<br />

from MoMA regarding why this initiative<br />

is important to them, and what it will mean to them<br />

once it is accomplished. FURY will also analyze the<br />

musuem’s assets and identify qualifications that make<br />

artists “great.” Some qualifications, like technical expertise,<br />

effective communication, understanding of<br />

cultural values, and in-depth emotional connection to<br />

work and career path, will be measured. These findings<br />

will be shared with other art institutions around the<br />

world and a global grading system will be developed<br />

FALL 2016

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN<br />

QUANTIFYING “GREATNESS”<br />

To establish a comprehensive profile for great art, FURY Art Advisory conducted a series of evaluations of art and artists in the Museum<br />

of Modern Art’s collection during the discovery phase of the project. Two sample asses<strong>sm</strong>ents – one deemed highly normative, the other<br />

far less so – are presented below.<br />

n Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)<br />

n Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889)<br />

10<br />

This famed Dutch painter sets the standard for great<br />

art. Evaluated using 10 key art-related criteria, Rembrandt<br />

rated a 9.3 on the FURY Greatness Quotient<br />

(FGQ) scale.<br />

10<br />

An academic painter of historic, allegorical and<br />

portrait works in the Beaux-Arts style, Cabanel only<br />

achieved a 4.1 on the FGQ scale, well below the<br />

“greatness” mean of 7.3.<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

Technical skill<br />

Functional<br />

viability<br />

Originality<br />

Complexity<br />

of work<br />

Cultural value<br />

Effective relay<br />

of message<br />

Career longevity<br />

Emotional connection<br />

with viewer<br />

Market value<br />

Influence<br />

among peers<br />

TRENDS IN “GREATNESS”<br />

FURY tracked annual visits to view works that scored 7.3 or higher on the FSQ scale in selected musuems around the country over four<br />

decades. The results provide a picture of the appeal of great works over time. It can be seen that since the 1970s, Pop Art’s greatness<br />

has grown steadily, while Rennaisance art, despite its high FSQ rating, has remained largely flat.<br />

Total visits<br />

70M<br />

60M<br />

50M<br />

40M<br />

30M<br />

20M<br />

10M<br />

0<br />

Rennaisance<br />

Neoclassical<br />

Impressioni<strong>sm</strong><br />

Cubi<strong>sm</strong><br />

Abstract Expressioni<strong>sm</strong><br />

Pop Art<br />

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015<br />

Charts and data courtesy FURY Art Advisory<br />

0<br />

Technical skill<br />

Functional<br />

viability<br />

Originality<br />

Complexity<br />

of work<br />

Cultural value<br />

Effective relay<br />

of message<br />

Career longevity<br />

Emotional connection<br />

with viewer<br />

Market value<br />

Influence<br />

among peers<br />

THE CONSULTING TEAM<br />

FURY Art Advisory (FAA) has built a<br />

strong reputation for successfully<br />

helping private collectors and worldrenowned<br />

art institutions build collections<br />

with a mission and develop<br />

strategic projects. Clients include the<br />

Furyaka<br />

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow,<br />

the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., and<br />

the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.<br />

Michelle Furyaka, president and CEO of FAA, has<br />

worked with clients in Moscow, New York, Berlin<br />

and London. Under her guidance, FAA has advised<br />

collectors and institutions in making educated acquisitions<br />

when expanding existing collections or when<br />

branching out into other art styles and genres. An<br />

art collector herself who was born in Russia, Furyaka,<br />

favors work by the Soviet-era Nonconformist artists.<br />

15

16<br />

ENGAGED Visitors to the Musuem of Modern Art<br />

crowd its second-floor galleries in search of great art.<br />

Ingfbruno photo<br />

so that artists, museums and the public can all collaborate<br />

and be part of the “make art great again”<br />

initiative.<br />

Expected results: The engagement with FURY<br />

Art Advisory provided a head start for MoMA. The<br />

benchmarking study allowed the museum to develop<br />

superior and effective plans to achieve their<br />

specific goals. MoMA set out to start a movement<br />

to “make art great again.” Through various social<br />

media campaigns, the museum and its affiliates<br />

were able to create an awareness of the initiative.<br />

The various marketing campaigns conducted by<br />

FURY created a following for the museum’s mission.<br />

People who are dissatisfied with the direction<br />

art is taking now have a cause to join. FURY’s<br />

proposed grading system and plans for “making<br />

art great again” will be published on the MoMA’s<br />

website. FURY also suggested beginning a dialogue<br />

with emerging artists to engage the public<br />

in their creative process. Research indicates that<br />

many people feel art is meaningless because they<br />

don’t understand what the artist is trying to convey.<br />

FURY determined that this gap can be closed<br />

by examining previous art movements and quantifying<br />

the way they were initially received by the<br />

public. FURY Art Advisory will demonstrate that<br />

change is necessary in order to make art meaningful<br />

and thus “great again.” What remains is for<br />

MoMA to implement recommended strategies and<br />

launch the “great art” roadmap.<br />

n<br />

THE CONSERVATOR<br />

Almost every single artifact in a museum on<br />

exhibition (of any age) has had intervention.<br />

The department that stabilizes artwork so it<br />

can be exhibited without its condition being<br />

questioned is the museum conservation department.<br />

Art conservators are different than art restorers. The<br />

difference is best highlighted in the following example.<br />

If one has a sword blade with spot areas of corrosion,<br />

a conservator would treat those tiny areas and not<br />

By Erica<br />

James<br />

re-galvanize it (an act of restoration). Theoretically,<br />

conservators don’t need things to<br />

look new. This is done for a variety of reasons.<br />

In terms of the sword blade, the existing metal is<br />

the original material; in preserving this material, the<br />

conservator maintains the value (monetary and otherwise)<br />

of the sword. More importantly, this less invasive<br />

approach preserves the material for future scholarship,<br />

etc.<br />

Allow me to briefly give you a bit of background. I<br />

have been engaged in the art conservation field for 26<br />

years, starting when I first became (passionately) interested<br />

at age 18. I completed undergraduate work in<br />

studio art, art history and chemistry, before going on<br />

to graduate school where I specialized in painting conservation<br />

with an interest in modern materials. Two<br />

more fellowships followed, and then private practice<br />

and a position in a museum. Typically, a painting conservator<br />

would keep a position like that for life. I was<br />

out in less than five years.<br />

The question is why? It wasn’t the fact that in a field<br />

that is 95 percent female, males hold most of the positions<br />

as heads of museum conservation labs. As ingrained<br />

as sexi<strong>sm</strong> is in the museum world, that wasn’t<br />

the reason. The reason was that as time dragged by in<br />

my dream job, I gradually started to sense the workings,<br />

the light thrum and the endless combustion of<br />

a “Museum Value Machine.” Think of the nonsensical<br />

machine paintings by the early 20th-century artist<br />

Francis Picabia. A Picabia machine is incredibly detailed.<br />

Exacting, elegant and specific. And people stand<br />

back and admire its specificity. There is only one problem.<br />

The machine doesn’t work, and its dysfunctionality<br />

is systemic. One plug fires, creating movement in a<br />

wheel whose only output is noise and a requirement<br />

for more action. The situation with museum conservation<br />

is like that, but even more complicated. Think of<br />

one of those strange vehicles (only more heavily detailed)<br />

from an early Mad Max film. Hoses, wires and<br />

FALL 2016

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN<br />

tubes in abundance. If one piece was removed, the mechanical<br />

puzzle would be incomplete. So it is with the<br />

Museum Value Machine.<br />

Typically, art conservation in the museum environment<br />

isn’t about the art, although it plays a pivotal role<br />

in how art is valued. If art conservation isn’t about art,<br />

what, then is it about? How does the Museum Value<br />

Machine transform the manifestation of a creative act<br />

into a thing so specialized and rarified that its most significant<br />

valuation is monetary?<br />

The more specialized and rarified a museum’s art<br />

product appears to be, the more luxurious it becomes.<br />

Who can afford such luxury? People who have money<br />

– in the case of art, a lot of money. And thus the<br />

inflation of art value by the Museum<br />

Value Machine dictates big museum<br />

(and <strong>sm</strong>all museum) policy.<br />

As conservators, we are expected to<br />

be completely devoid of interest in this<br />

monetary valuation. Art conservators<br />

aren’t appraisers. My classic response<br />

to a private client who asks if something<br />

is worth conserving (i.e., will<br />

cost less to conserve than it is worth)<br />

is, “If it’s worth it to you, it’s worth it.”<br />

But often, museum conservation will<br />

increase the monetary value of an artifact.<br />

This added value is highly disruptive<br />

to the conservation psyche that<br />

prides itself in being neutral or simply<br />

absent when the valuation of art comes<br />

into play.<br />

In order to understand the big<br />

picture of Museum Value Machine<br />

pathology, one must go behind the<br />

scenes. First, who works in a museum?<br />

On top are board members who have<br />

big art collections and dictate policy<br />

so their collections, often stored at the<br />

museum for free, are in a secure place.<br />

Board members also give money to purchase artworks<br />

whose acquisition by a museum not only increases the<br />

value of the artwork acquired, but perhaps also increases<br />

that of artworks that already reside at the museum.<br />

Museum board members curry the most favor<br />

because they not only have artwork that may someday<br />

be donated to the museum, but they also have money;<br />

and art and money are the fuel that make the Museum<br />

Value Machine go.<br />

Next in line is the museum director, who executes<br />

the vision of the board and heroically shuffles and reorganizes<br />

the employees. Museum directors also have<br />

I gradually started to<br />

sense the workings,<br />

the light thrum and the<br />

endless combustion of a<br />

‘Museum Value Machine.’<br />

Think of the nonsensical<br />

machine paintings by<br />

the early 20th-century<br />

artist Francis Picabia.<br />

an important say in who the musuem’s curators are.<br />

The curators manage respective collections based on<br />

their art history expertise and are in charge of coming<br />

up with exhibition ideas, maintaining relationships<br />

with other institutions to facilitate loans, buying new<br />

artwork and sometimes deaccessioning pieces. They<br />

also maintain relationships with the board and fulfill<br />

board requests. If a board member can get his or her<br />

artwork into an exhibition, its exposure increases its<br />

potential monetary value. Alternatively, if an exhibition<br />

can be founded on a specific group of paintings,<br />

their exposure – and value – also goes up.<br />

In other words, the strategic handling and promotion<br />

of artwork in a collection potentially increases<br />

its value for present and potential<br />

owners – board members and museums,<br />

respectively. A rising tide does,<br />

indeed, lift all boats. And the curator<br />

is beholden to board member requests<br />

because those board members<br />

not only have the money to purchase<br />

other artworks (hear the heavy gavel<br />

drop down at your local art retailer),<br />

but also have art collections that may<br />

eventually come to the museum. The<br />

curator does everything to make sure<br />

the board members are appeased. This<br />

can include a whole range of activities,<br />

from professional discussions about<br />

the management of a board member’s<br />

collection, to the facilitation of a board<br />

member’s private event at the museum<br />

after hours.<br />

For all intents and purposes, curatorial<br />

activities serve as the oil for the<br />

Museum Value Machine – constantly<br />

lubricating the works to minimize any<br />

sort of friction.<br />

And who are the curators in<br />

charge of? Well, us. The outwardly<br />

high-minded, and inwardly hand-wringing, conservators.<br />

The only power that conservators have in a museum<br />

is a claim to this high-minded specificity. Art conservators<br />

“treat” paintings and objects for exhibition.<br />

We take something that isn’t up to snuff and propagate<br />

the myth that it is exactly as the artist intended. That it<br />

hasn’t aged. We blind people with science and include<br />

the results in glossy catalogues on exhibitions that are<br />

no more in our control than are the laws of physics.<br />

Make no mistake about it, however. Conservators are<br />

tradespeople. We fix things. We may use an enormous<br />

amount of science to do it (making us seem all the<br />

See a video on<br />

conserving modern<br />

art at artenol.org.<br />

17

MAKING IT LOOK GOOD<br />

In preserving an art object, conservators use<br />

tested methods that restore the item to as close to<br />

its original condition as possible for as long a period<br />

as possible. Guidelines included applying minimal<br />

intervention, using appropriate materials and<br />

reversible methods, and fully documenting whatever<br />

work is done.<br />

Because preservation<br />

techniques improve<br />

over time, emphasis<br />

is now placed on the<br />

reversibility of the<br />

conservation processes<br />

employed. That<br />

reduces potential<br />

problems for future<br />

CLEANUP The conservation lab at the Smithsonian<br />

American Art Museum, above, is a typical facility for<br />

conservation and restoration of valuable artworks.<br />

At left, an icon is gently cleaned with a cotton swab<br />

and distilled water. wikimedia.org photos<br />

treatments. Conservation is usually reserved for<br />

works of historial or aesthetic importance; their rarity,<br />

representativeness and communicative power are<br />

also taken into consideration by conservators.<br />

18<br />

more specialized and rarified), but we basically make<br />

those things the museum so desperately needs on its<br />

walls look presentable. This often increases the value<br />

of the artwork.<br />

Here is an example of how the conservation section of<br />

the Museum Value Machine works. A modern painting<br />

is going out on loan. The curator assigns it to a modern<br />

painting conservator to be conserved. The curator<br />

comes in and stands over the painting with the conservator<br />

and ruminates on how it should look. Intervening<br />

too much, altering it too severely could decrease a painting’s<br />

value. A difficulty arises when mounting a large<br />

exhibition and paintings in a wide variety of conditions<br />

come from all over. The perfectly adequate painting my<br />

curator has pales in comparison to the pristine, relatively<br />

untouched painting that another museum is lending<br />

and (as it happens) will be placed right next to it. The<br />

couch looked great until I purchased those new drapes.<br />

And it isn’t a matter of moving the painting. These exhibitions<br />

are painstakingly planned out with every painting<br />

in the same position in every venue – false walls<br />

abound. It’s all about context, people. Or better yet, as<br />

in retail, location is everything.<br />

This is where it gets very noisy in the conservation<br />

section of the Museum Value Machine. The pressure<br />

to make a painting look presentable applies not only<br />

to itself, but to itself in comparison with its exhibition<br />

neighbors, and to a potential increase in its value. Pressure<br />

also comes from the board to mount a successful<br />

exhibition (not to mention the fact that if a board member<br />

is lending an artwork to the exhibition, it will be<br />

conserved for free) and from the public who has been<br />

conditioned to expect blockbuster exhibitions.<br />

By the way, the museum world pretty much assumes<br />

that while the average visitor may not know<br />

anything about art, he or she does understand “bigger<br />

is better.” Museums know that will draw crowds. The<br />

message museums put out to the general public isn’t<br />

something like “As a public institution, we act on your<br />

behalf to bring you an art experience that we hope will<br />

add meaning to your life.” It’s more along the lines of<br />

“This exhibition was brought to you by us. It’s a rare<br />

opportunity to see this artwork made by this popular<br />

artist during this time! Thank goodness it’s only our<br />

board that has paintings of this artist from this specific<br />

era, or we would never know what the artwork from<br />

this most rudimentary period was like! Let’s make it a<br />

blue-chip extravaganza!”<br />

The Museum Value Machine isn’t about the philanthropic<br />

sharing of art for the betterment of humanity.<br />

It is about the calculated sharing and borrowing of<br />

artwork to increase its exposure and monetary value.<br />

And conservation is a tool of this pragmati<strong>sm</strong>, serving<br />

as a sort of “check engine” light, should some portion<br />

of the museum machine require a tune-up.<br />

In a museum, there is always a ton of money, and no<br />

money at all. I worked for one institution with a billion-dollar<br />

endowment where its highest paid employee<br />

– the director, of course – was earning sometimes<br />

625% more than its lowest-paid employees (nearly<br />

everyone else). The glory days of a member of the social<br />

register taking one dollar a year to head a museum<br />

By the way, the museum world pretty<br />

much assumes that while the average visitor<br />

may not know anything about art, he or<br />

she does understand ‘bigger is better.’<br />

FALL 2016

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN<br />

are over. The days of that same director taking time to<br />

walk through the museum to check on the guard who<br />

was recently in the hospital are also long gone.<br />

While money always seems to be found to buy artwork<br />

at an inflated price, efforts to locate funds to provide<br />

a museum’s lowest-paid workers with a living<br />

wage are never made. It is a myth, really, that there is<br />

no money to be earned in the art world. There definitely<br />

is – just not for anyone who isn’t already wealthy. The<br />

romantic image of the starving artist and the glamour of<br />

the art world all play into the mystification<br />

of the museum world experience.<br />

Art conservation contributes<br />

to this mystification in a big way by<br />

simply fixing things and then tarting<br />

up the process with a lot of science<br />

and jargon. The conservation process<br />

is not without real value, but its practicality<br />

can assume a sanctimonious<br />

gloss under these conditions.<br />

The Museum Value Machine increases<br />

monetary value by conserving<br />

artwork, but it also contributes<br />

to increasing mystique by adopting<br />

a minimally invasive “hands-off”<br />

approach to the preservation of<br />

art. For example, there is no <strong>sm</strong>all<br />

amount of discussion involved in<br />

conserving a painting. Conservators<br />

may make very little compared to<br />

higher-level staff, but can wax philosophical<br />

about original intent and<br />

sing the praises of reversing “chemical<br />

degradation.”<br />

The irony here is that one would<br />

think that this intervention corresponds to the age of an<br />

artwork, that it is directly proportional to it – and that is<br />

often the case. The conservators of several-centuries-old<br />

“old yellow paintings” work very hard (sincerely so) to<br />

make them presentable to the public. But with the advent<br />

of newer materials used in newer works came new<br />

problems, and conservators of 20th-century works have<br />

their work cut out for them preserving modern and contemporary<br />

art. Such work also happens to have some of<br />

the highest valuations in art.<br />

For example, we modern conservators fret about<br />

the aging of materials that came into use during the<br />

last century (one word: plastics) and will do a bit less<br />

to conserve them because, well, who knows what to<br />

do? But you will rarely find a painting conservator<br />

admitting as much. Instead, the myth is perpetuated<br />

that we do less with modern work because we want<br />

DREAM JOB Conservator Erica<br />

James carefully cleans a contemporary<br />

art piece for eventual display in<br />

a museum. Photo courtesy Erica James<br />

to stay true to the original intent of the artist and that<br />

intent was ... to be ... abstract and conceptual. Again,<br />

not entirely disingenuous, but in the finer workings of<br />

the Museum Value Machine, these nuances enhance<br />

the art world’s mystique. Think of it as detailing the<br />

Museum Value Machine. It needn’t work to look good.<br />

By the time you get to contemporary art, the materials<br />

are so unpredictable in their longevity, and some of<br />

the artwork is so devoid of craft<strong>sm</strong>anship and – here’s<br />

the kicker – the value so HIGH, who even wants to<br />

touch them?<br />

Of course, the spin remains the<br />

same: We do less because we want to<br />

stay true to the original intent of the<br />

artist. And we don’t know what that<br />

is because it is all so ... conceptual.<br />

This becomes quite ephemeral<br />

when, for example, a conservator<br />

of contemporary art is the keeper of<br />

an “idea” by the artist. So, when the<br />

artwork has to be conserved, somehow<br />

the conservator lets the idea<br />

emerge from his or her lips like a<br />

Pythian priestess. Ideas are important,<br />

and intellectual property is, too.<br />

But it all gets very vague, contrived<br />

and practiced. If one has any common<br />

sense at all, it becomes quite<br />

apparent that a lot of this is made<br />

up. The emperor has no clothes.<br />

This wouldn’t be such a big deal<br />

if it wasn’t so insidious. But at the<br />

end of the day, like many things,<br />

it comes down to money. Because,<br />

although there are many ways to<br />

measure value, money is the driver for Museum Value<br />

Machine culture. Not freedom of expression, not passion,<br />

not beauty, not spirit, not creative drive, not intellectuali<strong>sm</strong>,<br />

not philosophy, not, not, not. Not anything<br />

you would expect or want it to be about. Most of all,<br />

what it isn’t about is the art.<br />

And, in those moments when one talks shop with<br />

other museum folks, precious few of them imbue the<br />

conversation with the following: “You know, it is just<br />

about the art for me. I just try to make it about the art.”<br />

The truth is, it never will be about the art in the Museum<br />

Value Machine’s infrastructure, because art only plays a<br />

very <strong>sm</strong>all role as fuel for the machine. Along with money,<br />

it is simply a currency that keeps museum culture<br />

running. And conservation, despite its best intentions, is<br />

never a means to an end, but only a barometer for what<br />

is best for any artifact by means of comparison. n<br />

19

THE INVESTOR<br />

20<br />

My first child was born on March 30th,<br />

2008, at the Portland Hospital in London.<br />

It was a momentous occasion, of course,<br />

for more then the usual reasons. In the<br />

heat of the moment, I decided to spend the night after<br />

the birth with my wife in her private room. The nurse<br />

brought in a cot, but I tossed and turned, unable to<br />

sleep. The birth of my son wasn’t the cause of my restless.<br />

At a time when everything in my life was about to<br />

change, I was thinking that my job needed<br />

changing, too.<br />

I wanted to be a role model for my<br />

son. That night, I decided I would follow my passion.<br />

When my paternity leave was over, the next day at<br />

work, I scheduled a meeting with my boss to discuss<br />

the terms of my exit. I told him I was quitting my job as<br />

a financial broker.<br />

So began my circuitous path to socially-engaged art<br />

and socially-responsible investing. After spending my<br />

early childhood in the former Soviet Union and emigrating<br />

to the United States in 1981 at the age of 9,<br />

I instinctively knew that capitali<strong>sm</strong> worked and communi<strong>sm</strong><br />

didn’t. That was reinforced when, right after<br />

graduation from college, my first job was in that<br />

bastion of capitali<strong>sm</strong>, the stock market. Working initially<br />

as an option trader on the Philadelphia Stock<br />

Exchange, and then within a year moving on to the<br />

American Stock Exchange in New York, I bought the<br />

neo-liberal story hook, line and sinker. I religiously<br />

read the Wall Street Journal and hungrily consumed the<br />

works of Ayn Rand. All of my inherent preconceptions<br />

about economic and societal rights and wrongs were<br />

reinforced and amplified.<br />

A change in my ironclad life philosophy came during<br />

the eight years my wife and I lived in England. We<br />

moved to London in 2001, a couple of months before<br />

the attacks on 9/11. It was a fortuitous move because I<br />

might have still been working at the American Stock<br />

Exchange, about a block from the World Trade Center.<br />

In London, I dove headfirst into the world of capital<br />

markets, first as a stock option trader, then moving on<br />

to be a broker of credit derivatives and then structured<br />

credit derivatives. With each new year, I was making<br />

more money, moving up through the ranks, eventually<br />

heading the European brokerage team at the second<br />

biggest interdealer broker in the world. But something<br />

was missing. I found the days at work mind-numb-<br />

By Gary<br />

Krimershmoys<br />

ROLE MODEL Artenol’s publisher, Gary Krimershmoys,<br />

organizing the hanging of the magazine's recent "The<br />

Revolution Continues"show in Manhattan. Krimershmoys<br />

has found renewed purpose in socially responsible investing.<br />

Artenol photo<br />

MAKING A DIFFERENCE<br />

Here are a few things practitioners of sociallyengaged<br />

art and socially-responsible investing<br />

can learn from each other.<br />

n Socially engaged artists can tap into institutional<br />

pools of money, perhaps by offering art from<br />

funded projects for corporate collections. Though<br />

this can associate a project with a commercial<br />

entity, the impact the artist’s work has on the<br />

community is key. Donating pieces to the corporate<br />

sponsor serves a larger purpose.<br />

n Impact investment funds can incorporate<br />

artists and cultural nonprofits into urban renewal<br />

projects while engaging directly with underserved<br />

communities.<br />

n Artists are often adept at generating publicity.<br />

They can create interest in stories that the media<br />

might overlook. By teaming up with SRI funds,<br />

artists can highlight some of the biggest offenders<br />

in the corporate space. This can be similar to<br />

what Greenpeace does with polluters, but on a<br />

wider, multi-industry scale.<br />

Currently, both socially responsible investing and<br />

socially-engaged art are in the growth phase. In<br />

20 years, it's very likely both will be considered<br />

mainstream, no longer niche approaches in the<br />

larger systems where they operate.<br />

FALL 2016

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN<br />

It was the feeling of serenity that permeated<br />

my otherwise-frantic mind whenever I spent<br />

a few hours at a museum that won me over.<br />

ing and the nights entertaining clients (who mostly<br />

couldn’t talk about anything other then the markets or<br />

making and spending money) physically and emotionally<br />

abusive. I found that the lifestyle didn’t produce<br />

for me real, basic happiness.<br />

Another crack in my philosophical foundation<br />

formed when I saw that there could be an economic<br />

system different from Rand’s pure capitali<strong>sm</strong>. Experiencing<br />

the European economic experiment that mixed<br />

capitali<strong>sm</strong> and sociali<strong>sm</strong>, showed me, to my surprise,<br />

that people didn’t derive all of their happiness from<br />

economic prosperity. I started to believe that contentedness<br />

could be found in shared purposes and stories,<br />

more so than through the often-egocentric materiali<strong>sm</strong><br />

of financial success.<br />

With the birth of my son, I decided to extricate myself<br />

from the lucrative brokerage business. To achieve<br />

a deeper satisfaction in my working life, I inventoried<br />

my passions to see which of them might accommodate<br />

a career shift.<br />

After about a year of considerable soul searching, I<br />

settled on the art world. I was won over by the feeling<br />

of serenity that permeated my otherwise frantic mind<br />

whenever I spent a few hours at a museum. That,<br />

along with a few guided gallery tours and the start of a<br />

<strong>sm</strong>all art collection, became the foundation of my new<br />

career. My ego whispered, “If you can be successful<br />

in the cutthroat world of high-level finance, how hard<br />

can it be to succeed in the art world?” And so the next<br />

phase of my journey began.<br />

The art world seemed a mysterious cauldron of social<br />

commentary and engagement, human purpose<br />

and ego, vanity and an alternative-asset class. These<br />

contradictions drew me in, and I was soon managing<br />

an international art advisory business, and eventually<br />

a gallery in New York’s trendy Chelsea neighborhood.<br />

In my new career, I found chances to combine ideas<br />

of social progress with a business that had a spiritual<br />

joy to it as part of the cultural commentary. The appeal<br />

of contemporary art that had a social message and was<br />

politically engaged was manifested for me in the first<br />

pop-up exhibition I curated, one where I enabled Alex<br />

Melamid (the founder of Artenol) to “cure” people<br />

with the power of art through an entity called the Art<br />

Healing Ministry (AHM). Set up as a kind of gallery/<br />

dispensary, people could come to the AHM to get their<br />

maladies cured through the power of art.<br />

Other projects over the years ranged from the purely<br />

commercial to the purely conceptual. These had<br />

wide-ranging degrees of success, measured mostly<br />

by the yardstick of magazine reviews and occasional<br />

sales of artworks. The conclusion of my exhibition career<br />

came with a last show at Vohn Gallery, an exhibit<br />

called “AUTOIMMUNE.” Artworks shown diagnosed<br />

the human imprint on the world, as a doctor might diagnose<br />

a patient’s disease.<br />

One of the goals of AUTOIMMUNE was to examine<br />

current social questions, the cultural moment, with a<br />

fresh eye toward finding answers where none seemed<br />

forthcoming. There was also, looking back at on it, an<br />

unconscious pull toward combining art and medicine.<br />

That pull culminated in Artenol, as characterized by<br />

the magazine’s name (taking inspiration from the drug<br />

Tylenol).<br />

In the 1960s, “land art” combined natural elements<br />

in artistic ways to create pieces that lived and breathed<br />

in the environment they occupied. Going back further,<br />

Art Brut was a movement built on the ash heap of the<br />

Second World War, a rejection of a civilization that<br />

could perpetrate murder and genocide on an industrial<br />

scale. Art movements of this sort helped to create the<br />

recent wave of socially engaged art. These works use<br />

communities, collaboration, ephemerality and public<br />

engagement in a reaction, in my mind, to materiali<strong>sm</strong><br />

and the commodification of contemporary art.<br />

I've seen and appreciated the impact that socially-engaged<br />

art could have, from Paul Chen’s New<br />

Orleans performance of “Waiting for Godot” in the<br />

wake of Hurricane Katrina, to Theaster Gates’ projects<br />

in the blighted areas of Chicago and Rick Lowe’s<br />

effort to transform neglected shotgun houses in<br />

Houston into art.<br />

Realizing that this type of artist-instigated social impact,<br />

on a scale that mattered, can only be financed by<br />

cultural institutions, major non-profits and deep-pocketed<br />

commercial galleries (unlike the one that I was<br />

a part of), my research took me back to the world of<br />

finance, to those capital institutions that also tried to<br />

improve the environment, create social cohesion and<br />

foster corporate accountability. Their efforts seemed to<br />

have spiritual affinity with those artists that produced<br />

socially-engaged art.<br />

As artists try to change the course of society’s arc<br />

by influencing culture through empathy and a bit of<br />

spectacle, so do a few warriors in the financial sphere<br />

try to change the direction of the steamroller that is<br />

world finance. These entreprenuers’ efforts have been<br />

dubbed “Socially Responsible Investing” (SRI). The<br />

Find a link to<br />

an article on<br />

socially responsible<br />

investing<br />

in Forbes at<br />

artenol.org.<br />

21

22<br />

field also has other strategies that fall under the<br />

same umbrella, with names like “Sustainable and<br />

Responsible Investing” and “Environmental, Social<br />

and Governance” screening.<br />

SRI pioneers, possibly taking a cue from the early<br />

Abolitionists’ rejection of the slave trade, created a<br />

movement that was a key in dealing a death blow<br />

to the apartheid regime of South Africa. These investors<br />

are currently dealing with some of society’s<br />

most pressing issues, like the impact of human activity<br />

on the environment, the role of finance in society<br />

and income inequality.<br />

Currently, it’s institutional investors like pension<br />

funds and major non-profits that are largely leading<br />

the SRI revolution. These funds try to foment change<br />

by pooling their shares and voting as a bloc for progressive<br />

resolutions put before company boards.<br />

They use the media to build pressure for change, and<br />

they engage with communities where companies<br />

operate and are headquartered. By using these techniques,<br />

SRI investors can successfully demand inclusion<br />

of those communities into company mandates.<br />

In this sphere, a positive version of trickle-down<br />

economics is becoming increasingly common. SRI<br />

strategies are being adopted more and more by individual<br />

investors. The cutting-edge of the movement<br />

is “Impact” investing, where investors can put<br />

their money directly into projects they find appealing.<br />

The result is something like a merger of philanthropy<br />

and investment – a pairing that at one time<br />

was considered an unholy marriage.<br />

Today, American society faces a choice between<br />

two paths. One path leads to fear, separation, materiali<strong>sm</strong><br />

and violence. The other moves toward an<br />

understanding that humans are part of an interconnected<br />

whole that comprises life on this planet, and<br />

advocates cohesion and environmental stewardship.<br />

Both socially responsible investing and socially<br />

engaged art have a part to play in the second trajectory.<br />

Even if they don’t work perfectly, the intention<br />

of both fields is noble and worth supporting. If<br />

the financial industry can show a soft side through<br />

SRI, socially engaged art can be one of the beacons<br />

that draws participants away from the status quo<br />

and into a less-commoditized, more open and embracing<br />

art world.<br />

My assertion and hope is that, in 20 years, socially<br />

responsible investing and socially engaged art<br />

will no longer comprise a niche investment strategy<br />

but will be a viable part of the global financial<br />

mainstream.<br />

n<br />

THE ARTWORKER<br />

They’re as much a part of our art museum<br />

experience as are white walls and hushed,<br />

expansive interiors. We look beyond them,<br />

moving from one displayed piece to another,<br />

careful to keep a respectful distance.<br />

When we do notice musuem guards, they seem bored,<br />

vaguely disdainful, footsore. Roused from lethargy,<br />

they proffer directions to the restrooms or reprimand<br />

the visitor who tries to touch. They all seem vaguely<br />

By Rowling the same – salaried employees doing a<br />

Dord job that, like any other, is both a grind<br />

and a paycheck.<br />

But Artenol has uncovered one musuem guard who<br />

is not what he seems. He is an artist whose art is a kind<br />

of unending performance, a marathon of tedium spent<br />

in commune with some of the art world’s great masterworks.<br />

He sees his presence as one element that, for<br />

museumgoers, makes great art great. He agreed to talk<br />

about his work, though he asked that we not use his<br />

name or mention where he is employed, saying only<br />

that he is “on exhibit” 40 hours a week at a major museum<br />

in the New York area. Our interview took place<br />

in August during a union-mandated break in his regular<br />

work shift.<br />

I understand that you were trained as an artist and have<br />

a degree from Yale.<br />

Yes, I have an MA in color theory. My thesis was on<br />

17th-century egg tempera pigment variations.<br />

But you’re now a museum guard?<br />

Officially, yes, that’s my title, though I prefer to call<br />

myself a facilitator/collaborator.<br />

A facilitator ... what?<br />

Facilitator/collaborator. I view myself as an artwork<br />

on display along with the more conventional pieces<br />

on the wall and on pedestals. They and I are part of<br />

the overall art environment in the museum. I am an<br />

extension of them, as they are of me.<br />

How so?<br />

My presence confers meaning, signifies a valuation.<br />

I represent a judgment about whatever art is<br />

present in the space with me. The fact that I’m here<br />

tacitly implies to visitors that the work on the wall is<br />

great. And, conversely, the fact that a piece merits a<br />

place in the museum’s galleries imbues my presence<br />

with a gravitas it otherwise would lack. Without<br />

these masterpieces on the wall, I’m just another secu-<br />

FALL 2016

MAKE ART GREAT AGAIN<br />

INTERACTIVE<br />

EXHIBIT<br />

rity guard at a 7-Eleven.<br />

So how do you see yourself as an extension of the art you<br />

guard?<br />

You know, “guard” is really the wrong word. That<br />

implies division, distance. The art and I are one, in<br />

fact. What I do is I facilitate a piece’s entry into contemporary<br />

life-space.<br />

In what way?<br />

I provide a context, just as the museum space does.<br />

But the fact that I am a living, sentient being, just like<br />

the visitors themselves, gives me an expanded role. I<br />

instill in the art an immediacy it would otherwise not<br />

have. I bring it into the here-and-now.<br />

You mean you’re a kind of bridge between visitor and<br />

art?<br />

Yes, that’s a good way to put it. The artworks and<br />

I collaborate to create a contemporary experience for<br />

the visitors, even though the pieces on exhibit may<br />

be decades or even centuries old. In that way, I make<br />

great art great again – on a daily basis, if you think<br />

Artenol photo<br />

about it. That’s the core of my work, a collaboration<br />

that results in the revitalization of hoary artifacts.<br />

That makes them relevant to the present. Without me,<br />

a great artwork’s meaning is much diminished.<br />

You’re speaking of its monetary value? Meaning that<br />

because a so-called guard is present, the art has worth?<br />

No, no – though that might be how it appears. I<br />

mean that my presence gives art an importance in<br />

terms of its intellectual and social worth. Its greatness,<br />

regardless of its market value. I’m a sign of an<br />

artwork’s absolute greatness.<br />

So if someone in a blue blazer is in the room, the art is<br />

great?<br />

Only if he’s awake (laughs). Really, it’s not so simple<br />

as that. There needs to be a conscious effort on the<br />

part of the “guard” to complete the facilitation. There<br />

are subtle ways to do that, but that’s the part of my art<br />