Shakespeare Magazine 07

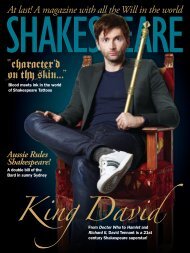

Kenneth Branagh is cover star of Shakespeare Magazine 07, as the issue's theme is Great Shakespeare Actors. Stanley Wells discusses his book on the subject, while Antony Sher reveals what it's like to play Falstaff. We also go behind the scenes of the My Shakespeare TV series, and Zoe Waites chats about playing Rosalind in the USA. Other highlights include Shakespeare in Turkey, Shakespeare Opera, and the real story of Shakespeare and the Essex Plot. All this, and the Russian fans who made their own edition of David Tennant's Richard II!

Kenneth Branagh is cover star of Shakespeare Magazine 07, as the issue's theme is Great Shakespeare Actors. Stanley Wells discusses his book on the subject, while Antony Sher reveals what it's like to play Falstaff. We also go behind the scenes of the My Shakespeare TV series, and Zoe Waites chats about playing Rosalind in the USA. Other highlights include Shakespeare in Turkey, Shakespeare Opera, and the real story of Shakespeare and the Essex Plot. All this, and the Russian fans who made their own edition of David Tennant's Richard II!

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Essex Plot<br />

“Staging the deposition of a<br />

king in front of a fickle mob<br />

could have been politically if<br />

not physically dangerous”<br />

The earliest records of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s play<br />

Richard II have caused scholars to date its<br />

composition to 1595, six years before the<br />

failed revolt. Until 8 February 1601, the<br />

day of Essex’s revolt, no evidence exists that<br />

indicates the Crown was interested in Richard<br />

II. On this day, Augustine Phillips, one of<br />

the members of the Lord Chamberlain’s<br />

Men, testified before Queen Elizabeth’s Privy<br />

Council, her cabinet of royal advisors, that<br />

subordinates of Essex contracted the players<br />

to: “have the play of the deposing and killing<br />

of King Richard II to be played… promising<br />

to get them [forty shillings] more than<br />

their ordinary to play it… and so played it<br />

accordingly.”<br />

Richard II was an old play; the two rival<br />

theatres of the day presented plays in repertory,<br />

with rotating schedules including new plays.<br />

As Richard II was six years old, the players,<br />

who had learned and presented many more<br />

plays in the intervening years, protested. But<br />

Essex’s men would have no other play. The<br />

Lord Chamberlain’s Men would not play<br />

Richard II unless they had extra payment to<br />

defray the anticipated loss. Being paid forty<br />

shillings for a command performance would<br />

be a considerable sum. Philip Henslowe,<br />

manager of rival company The Lord Admiral’s<br />

Men, kept an assiduous diary of daily incomes<br />

for his theatre, and this diary has survived. In<br />

it we find that forty shillings was a common<br />

but sporadic catch in the London theatre at<br />

the time. Henslowe’s Diaries note that, in<br />

December 1594, seven plays made at least<br />

a forty shilling gate in a single showing,<br />

and many plays which made this sum were<br />

premiers of new works. In the case of the Essex<br />

performance, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men<br />

were paid as much as a successful opening<br />

performance, and those forty shillings were in<br />

addition to the “ordinary to play it”, or the fee<br />

for a command performance, which could be<br />

considerably more.<br />

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in securing<br />

more money for their play may well have saved<br />

their lives. If they had truly been conspirators,<br />

then their politics might have taken a turn<br />

away from financial concerns. Rebellion<br />

would likely take precedence over personal<br />

income. If the Privy Council also followed<br />

this reckoning, then the forty shillings was<br />

evidence for the innocence of the players.<br />

If the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were truly<br />

dedicated to Essex’s cause, they likely would<br />

not have pointed out the possible financial<br />

risk. To the Privy Council, a group of players<br />

concerned about their incomes agreed to play<br />

Richard II providing they received a security<br />

from monetary loss. Because Richard II was<br />

of no great matter to the players other than as<br />

a matter of income, they were likely not Essex<br />

supporters. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in<br />

insisting upon a financial surety against loss,<br />

proved more interested in the gate than the<br />

state and so indicated their innocence.<br />

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men had<br />

every reason to avoid offending the Crown.<br />

Playwriting in the English Renaissance was<br />

dangerous business, and William <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

knew it. In 1597, his fellow playwright<br />

Thomas Nashe fled the country following<br />

his arrest after the controversial and nowlost<br />

play The Isle of Dogs. His writings were<br />

subsequently suppressed and burned. Ben<br />

Jonson was also imprisoned for The Isle of<br />

Dogs and would return to the clink in 1605<br />

with Marston and Chapman for Eastward<br />

Ho. In 1625, the Crown imprisoned Thomas<br />

Middleton and all of the actors from A Game<br />

At Chess, as the play satirised the Spanish<br />

Ambassador. These playwrights and actors’<br />

accusers put them in jail for mere slander.<br />

For possible sedition, which meant in that<br />

time “a concerted movement to overthrow an<br />

established government”, <strong>Shakespeare</strong> would<br />

have been charged with High Treason. Had<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> served at all as an accomplice to<br />

treason, his head would have wound up on a<br />

spike over Traitor’s Gate.<br />

44 SHAKESPEARE magazine