Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

In August 1946, veterans Alonza<br />

Brooks and Richard Gordon were murdered<br />

<strong>in</strong> Marshall, Texas, after becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> labor disputes with<br />

their employers. When found, Mr.<br />

Brooks’s body bore signs of strangulation,<br />

while Mr. Gordon’s throat was<br />

slashed and his body appeared to<br />

have been tied to the rear of an automobile<br />

and dragged. 137<br />

Maceo Snipes had served <strong>in</strong> the<br />

army for two and a half years and received<br />

an honorable discharge when he returned home to Taylor County, Georgia, to farm<br />

his father’s land. On July 17, 1946, Mr. Snipes voted <strong>in</strong> the Democratic primary for governor.<br />

The next day, several white men <strong>in</strong> a pick-up truck went to Mr. Snipes’s house and a white<br />

veteran named Edward Williamson shot him. Mr. Snipes walked for several miles seek<strong>in</strong>g<br />

help, but died before he could f<strong>in</strong>d any. Williamson, who belonged to a politically powerful<br />

family, told a coroner’s <strong>in</strong>quest that he had gone to collect a debt from Mr. Snipes and Mr.<br />

Snipes pulled a knife on him. The <strong>in</strong>quest ruled the kill<strong>in</strong>g was an act of self-defense. Taylor<br />

County, Georgia, later honored its World War II veterans with two engraved, segregated<br />

plaques list<strong>in</strong>g white and black veterans separately. Though an <strong>in</strong>tegrated plaque was<br />

added <strong>in</strong> 2007, the segregated orig<strong>in</strong>als rema<strong>in</strong>ed. 138<br />

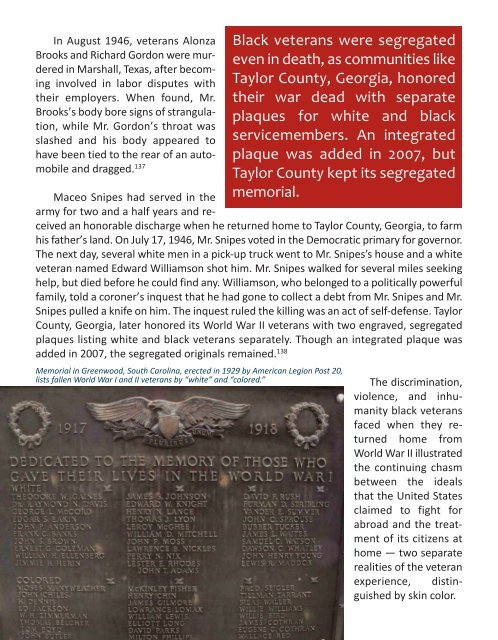

Memorial <strong>in</strong> Greenwood, South Carol<strong>in</strong>a, erected <strong>in</strong> 1929 by <strong>America</strong>n Legion Post 20,<br />

lists fallen World War I and II veterans by “white” and “colored.”<br />

Black veterans were segregated<br />

even <strong>in</strong> death, as communities like<br />

Taylor County, Georgia, honored<br />

their war dead with separate<br />

plaques for white and black<br />

servicemembers. An <strong>in</strong>tegrated<br />

plaque was added <strong>in</strong> 2007, but<br />

Taylor County kept its segregated<br />

memorial.<br />

The discrim<strong>in</strong>ation,<br />

violence, and <strong>in</strong>humanity<br />

black veterans<br />

faced when they returned<br />

home from<br />

World War II illustrated<br />

the cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g chasm<br />

between the ideals<br />

that the United States<br />

claimed to fight for<br />

abroad and the treatment<br />

of its citizens at<br />

home — two separate<br />

realities of the veteran<br />

experience, dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

by sk<strong>in</strong> color.