SAA

Nov2016_web

Nov2016_web

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

VIDEO GAMES AND ARCHAEOLOGY<br />

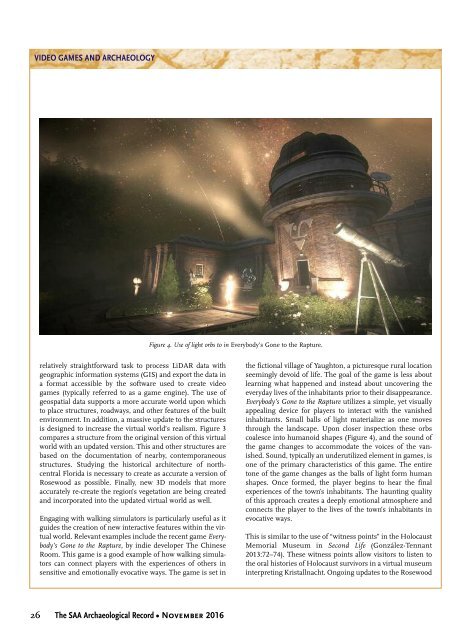

Figure 4. Use of light orbs to in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.<br />

relatively straightforward task to process LiDAR data with<br />

geographic information systems (GIS) and export the data in<br />

a format accessible by the software used to create video<br />

games (typically referred to as a game engine). The use of<br />

geospatial data supports a more accurate world upon which<br />

to place structures, roadways, and other features of the built<br />

environment. In addition, a massive update to the structures<br />

is designed to increase the virtual world’s realism. Figure 3<br />

compares a structure from the original version of this virtual<br />

world with an updated version. This and other structures are<br />

based on the documentation of nearby, contemporaneous<br />

structures. Studying the historical architecture of northcentral<br />

Florida is necessary to create as accurate a version of<br />

Rosewood as possible. Finally, new 3D models that more<br />

accurately re-create the region’s vegetation are being created<br />

and incorporated into the updated virtual world as well.<br />

Engaging with walking simulators is particularly useful as it<br />

guides the creation of new interactive features within the virtual<br />

world. Relevant examples include the recent game Everybody’s<br />

Gone to the Rapture, by indie developer The Chinese<br />

Room. This game is a good example of how walking simulators<br />

can connect players with the experiences of others in<br />

sensitive and emotionally evocative ways. The game is set in<br />

the fictional village of Yaughton, a picturesque rural location<br />

seemingly devoid of life. The goal of the game is less about<br />

learning what happened and instead about uncovering the<br />

everyday lives of the inhabitants prior to their disappearance.<br />

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture utilizes a simple, yet visually<br />

appealing device for players to interact with the vanished<br />

inhabitants. Small balls of light materialize as one moves<br />

through the landscape. Upon closer inspection these orbs<br />

coalesce into humanoid shapes (Figure 4), and the sound of<br />

the game changes to accommodate the voices of the vanished.<br />

Sound, typically an underutilized element in games, is<br />

one of the primary characteristics of this game. The entire<br />

tone of the game changes as the balls of light form human<br />

shapes. Once formed, the player begins to hear the final<br />

experiences of the town’s inhabitants. The haunting quality<br />

of this approach creates a deeply emotional atmosphere and<br />

connects the player to the lives of the town’s inhabitants in<br />

evocative ways.<br />

This is similar to the use of “witness points” in the Holocaust<br />

Memorial Museum in Second Life (González-Tennant<br />

2013:72–74). These witness points allow visitors to listen to<br />

the oral histories of Holocaust survivors in a virtual museum<br />

interpreting Kristallnacht. Ongoing updates to the Rosewood<br />

26 The <strong>SAA</strong> Archaeological Record • November 2016