JB Life January 2017

Volume 5 (January 2017) of JB Life, a publication of the Jeollabuk-do Center for International Affairs. Enjoy!

Volume 5 (January 2017) of JB Life, a publication of the Jeollabuk-do Center for International Affairs. Enjoy!

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SPORTS<br />

By Anjee DiSanto<br />

During and after the Rio Olympics, a video<br />

circulated of Park Sang-young, a 20-yearold<br />

Korean fencer who competed in the<br />

Games. With 10 points to his opponent’s 14 in the<br />

final match, Park could be seen visibly mouthing a<br />

string of words (in Korean) again and again. “I can<br />

do it. I can do it.” This scene in and of itself was<br />

touching, but was made even more so by the fact that<br />

Park could and did do it. Shortly after this self-pep<br />

talk he came from behind in a burst. The end result?<br />

A win, 15-14, and Korea’s first ever gold medal in<br />

men’s individual épée.<br />

While this was Korea’s first gold in that particular<br />

event, the country is no stranger to Olympic or<br />

international fencing wins. And yet… this is hardly<br />

the sport that outsiders would naturally associate<br />

with Korea if asked. In the minds of many, the sport<br />

tends to be stereotypically linked to svelt Europeans<br />

with long legs or arms. France. Italy. Hungary. Indeed,<br />

these countries boast the most overall medals<br />

throughout time in Olympic fencing and primarily<br />

dominated the sport in the competitions of old. Over<br />

time, though, the field of victors has spread.<br />

At the Amazing Iksan Fencing Club, instructor<br />

Lee Yeol admits between bouts that fencing wasn’t<br />

always so popular amongst Koreans. In the past, he<br />

says, people were mostly only recruited to competitive<br />

fencing clubs in middle and high school, on the<br />

condition that they had long legs or arms and had<br />

already shown to be good at sports. This is no<br />

longer the case. For one thing, as an analysis by<br />

the Australian group Sydney Sabre noted, Koreans<br />

do not generally excel at fencing through long<br />

limbs. Rather, they thrive on their natural speed<br />

and skilled footwork with elegant lunges. Coaches<br />

further emphasize this through vigorous leg exercises<br />

and techniques.<br />

And then there’s the fact that this is no longer<br />

just a competitive sport in Korea. Sponsors of the<br />

Korean Fencing Federation have promoted the activity<br />

as a way to get healthy in recent years, so<br />

nowadays, it’s no surprise to find fencing practices<br />

full of all ages, genders, and shapes.<br />

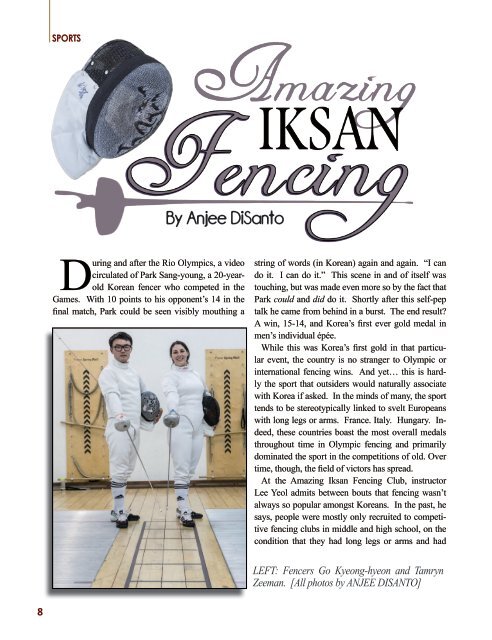

Such is the case at Amazing Iksan Fencing. Here<br />

we see clusters of young students (primarily female)<br />

and a spattering of differently aged adults,<br />

including Tamryn Zeeman, a South African public<br />

school teacher who has lived in Iksan for four years.<br />

Zeeman joined in April of 2015 on somewhat of a<br />

whim and ended up sticking with it. Though she<br />

admits that she and most others there have joined<br />

the sport far too late to be professionally competitive,<br />

she and others have still had the chance to<br />

develop a love for the sport and its benefits and a<br />

competitive spirit under their coaches, Kim Heewon,<br />

Lee Yeol, and main coach Ju Dal-nim.<br />

“Taking up fencing has benefited me mainly in<br />

health, keeping my mind sharp, and becoming<br />

more involved in the Korean community,” Zeeman<br />

says. “It has also made me aware of the high<br />

level that sports are carried out at in Korea,”<br />

The section of the club in which Zeeman participates<br />

does do some competitions around the peninsula,<br />

but these are not in the same league as those<br />

of Olympians and high-level competitors, some of<br />

whom have trained and do train locally (mostly via<br />

Iksan City Hall). For the hobbyists, they take the<br />

training more mildly, though their progress is nodoubt<br />

serious. Practices take place several times<br />

per week, and while somewhat short and businesslike,<br />

are still in good fun, with handshakes, chats,<br />

and laughs. Zeeman notes that these practices do<br />

get much longer and more intense prior to competitions,<br />

though.<br />

In terms of high-level competitions, the coaches<br />

here explain that the types of fencing vary by<br />

gender. Fencing typically splits into three areas:<br />

foil, which uses the lightest weapon and has the<br />

strictest rules; épée, which uses a sturdier blade<br />

and moves the “slowest”; and sabre, the most offensive<br />

and fastest (with blades sometimes moving<br />

as fast as bullets!). In Korea, they explain, women<br />

tend toward sabre on a competitive level, while<br />

men prefer épée.<br />

The coaches teaching here for the hobbyists and<br />

lower-level competitors focus on épée. This, they<br />

explain, may be a bit more approachable to the beginner.<br />

Around 16 people train in this particular<br />

club, while 30 train in the gym overall (including<br />

the elite competitors). In this group, the ratio is<br />

also 90 percent women.<br />

g<br />

LEFT: Fencers Go Kyeong-hyeon and Tamryn<br />

Zeeman. [All photos by ANJEE DISANTO]<br />

8