Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

are precariously close to the walls. Many times<br />

these studios are chosen because they have a<br />

good piano, enough music stands, and sufficient<br />

headphones and cue-mix capability to accommodate<br />

an orchestra of this size. Generally the<br />

microphone inventories, while decent, are insufficient<br />

to cover all the instrumentalists and singers<br />

with “A” line choices as well.<br />

One thing I’ve done to support this effort is<br />

to assemble my own personal mic collection.<br />

This enables me to supplement the chosen studio’s<br />

mic collection. I have a variety of condensers,<br />

ribbons and dynamics. I prefer using<br />

ribbon mics on brass and reeds. Until recently<br />

I had a pristine collection of RCA ribbon<br />

mics that I maintained and used over many<br />

years. There were two 44s, seven 77s and a BK5.<br />

I always used the 77s in a figure-8 pattern, as<br />

they are more of a match for the 44s and are<br />

about 6dB hotter in output that way. It has also<br />

helped the phase relationship in a large, multimic<br />

scheme.<br />

Several years ago, as I was about to go<br />

through another ribbon-mic collection re-ribboning<br />

ordeal, I came upon an opportunity to<br />

replace my collection. I had tried every ribbon<br />

mic manufactured. Only the AEA brand gave<br />

me the equivalent sound and mixing integrity<br />

that was comparable to the RCAs. However, they<br />

present the same basic challenges as the RCAs:<br />

lack of ribbon durability, low-ish output and too<br />

much weight for the type of small mic stands<br />

that are prevalent here in Chicago.<br />

When presented with the opportunity to<br />

test the Shure ribbon mics, I discovered that not<br />

only do they sound great, but they are as warm<br />

as the vintage ribbons and have nearly double<br />

the output, less distortion factor, a very narrow<br />

dead-side null and much more durable ribbons.<br />

They have the sound and mixing integrity that<br />

I require when choosing a mic for a purpose. I<br />

replaced my entire RCA collection with a collection<br />

of 13 Shure KSM 313s. This change was<br />

a definite step in a more modern direction for<br />

me. Now I can mic the entire brass and reed<br />

sections with this collection of the same microphone<br />

model. All 13 mics sound incredibly<br />

similar, articulate fast note passages wonderfully<br />

and, due to the increased null, provide me<br />

with better phase relationship than ever before.<br />

I then use the best condensers available (tube<br />

or FET) and the occasional dynamic for all my<br />

other miking needs.<br />

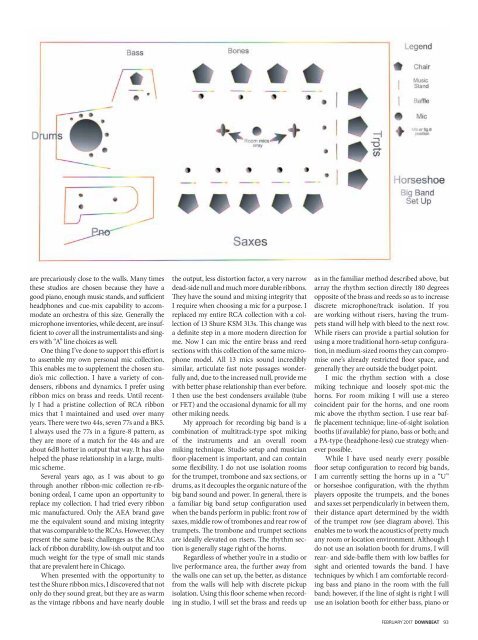

My approach for recording big band is a<br />

combination of multitrack-type spot miking<br />

of the instruments and an overall room<br />

miking technique. Studio setup and musician<br />

floor-placement is important, and can contain<br />

some flexibility. I do not use isolation rooms<br />

for the trumpet, trombone and sax sections, or<br />

drums, as it decouples the organic nature of the<br />

big band sound and power. In general, there is<br />

a familiar big band setup configuration used<br />

when the bands perform in public: front row of<br />

saxes, middle row of trombones and rear row of<br />

trumpets. The trombone and trumpet sections<br />

are ideally elevated on risers. The rhythm section<br />

is generally stage right of the horns.<br />

Regardless of whether you’re in a studio or<br />

live performance area, the further away from<br />

the walls one can set up, the better, as distance<br />

from the walls will help with discrete pickup<br />

isolation. Using this floor scheme when recording<br />

in studio, I will set the brass and reeds up<br />

as in the familiar method described above, but<br />

array the rhythm section directly 180 degrees<br />

opposite of the brass and reeds so as to increase<br />

discrete microphone/track isolation. If you<br />

are working without risers, having the trumpets<br />

stand will help with bleed to the next row.<br />

While risers can provide a partial solution for<br />

using a more traditional horn-setup configuration,<br />

in medium-sized rooms they can compromise<br />

one’s already restricted floor space, and<br />

generally they are outside the budget point.<br />

I mic the rhythm section with a close<br />

miking technique and loosely spot-mic the<br />

horns. For room miking I will use a stereo<br />

coincident pair for the horns, and one room<br />

mic above the rhythm section. I use rear baffle<br />

placement technique; line-of-sight isolation<br />

booths (if available) for piano, bass or both; and<br />

a PA-type (headphone-less) cue strategy whenever<br />

possible.<br />

While I have used nearly every possible<br />

floor setup configuration to record big bands,<br />

I am currently setting the horns up in a “U”<br />

or horseshoe configuration, with the rhythm<br />

players opposite the trumpets, and the bones<br />

and saxes set perpendicularly in between them,<br />

their distance apart determined by the width<br />

of the trumpet row (see diagram above). This<br />

enables me to work the acoustics of pretty much<br />

any room or location environment. Although I<br />

do not use an isolation booth for drums, I will<br />

rear- and side-baffle them with low baffles for<br />

sight and oriented towards the band. I have<br />

techniques by which I am comfortable recording<br />

bass and piano in the room with the full<br />

band; however, if the line of sight is right I will<br />

use an isolation booth for either bass, piano or<br />

FEBRUARY 2017 DOWNBEAT 93