- Page 2 and 3:

Mastering Technical Mathematics

- Page 4 and 5:

Mastering Technical Mathematics Thi

- Page 6 and 7:

To Tim, Samuel, and Tony

- Page 8 and 9:

For more information about this tit

- Page 10 and 11:

Contents ix Real Vs. Imaginary Numb

- Page 12 and 13:

Contents xi Navigator’s Polar Vs.

- Page 14 and 15:

Contents xiii Law of Large Numbers

- Page 16 and 17:

Introduction This book is intended

- Page 18 and 19:

Copyright © 2008, 1999 by The McGr

- Page 20 and 21:

1From Counting to Addition We’ve

- Page 22 and 23:

From Counting to Addition 5 Figure

- Page 24 and 25:

From Counting to Addition 7 Figure

- Page 26 and 27:

From Counting to Addition 9 Figure

- Page 28 and 29:

From Counting to Addition 11 Figure

- Page 30 and 31:

From Counting to Addition 13 WEIGHT

- Page 32 and 33:

From Counting to Addition 15 Figure

- Page 34 and 35:

13. In the United States, common li

- Page 36 and 37:

2Subtraction Just as addition is co

- Page 38 and 39:

Subtraction 21 the hundreds column,

- Page 40 and 41:

Subtraction 23 MAKING CHANGE This i

- Page 42 and 43:

Subtraction 25 Figure 2-6 Two metho

- Page 44 and 45:

3Multiplication Suppose you go into

- Page 46 and 47:

Multiplication 29 In Fig. 3-2A, exa

- Page 48 and 49:

Multiplication 31 Figure 3-3 An exa

- Page 50 and 51:

Multiplication 33 Figure 3-6 It doe

- Page 52 and 53:

Multiplication 35 Figure 3-9 Subtra

- Page 54 and 55:

Multiplication 37 Figure 3-12 Multi

- Page 56 and 57:

Multiplication 39 3. Multiply the f

- Page 58 and 59:

4Division Before the days of electr

- Page 60 and 61:

Division 43 Figure 4-2 A pictorial

- Page 62 and 63:

Division 45 MULTIPLICATION CHECKS D

- Page 64 and 65:

Division 47 Figure 4-6 At A, we can

- Page 66 and 67:

Division 49 In the example of Fig.

- Page 68 and 69:

Division 51 7/10 0.7 17/20 0.85 3

- Page 70 and 71:

Division 53 QUESTIONS AND PROBLEMS

- Page 72 and 73:

5Fractions Chapter 4 presented some

- Page 74 and 75:

Fractions 57 This line of reasoning

- Page 76 and 77:

Fractions 59 493/23 21.xxx . . . (

- Page 78 and 79:

Fractions 61 The numbers in the ori

- Page 80 and 81:

Fractions 63 5/12 25/60 3/10 18/6

- Page 82 and 83:

Fractions 65 “limiting values”

- Page 84 and 85:

Fractions 67 QUESTIONS AND PROBLEMS

- Page 86 and 87:

6Plane Polygons So far, this book h

- Page 88 and 89:

Plane Polygons 71 WHAT IS A SQUARE?

- Page 90 and 91:

Plane Polygons 73 inches is not the

- Page 92 and 93:

Plane Polygons 75 Figure 6-7 Two wa

- Page 94 and 95:

Plane Polygons 77 AREA OF AN OBTUSE

- Page 96 and 97:

Plane Polygons 79 Figure 6-11 Some

- Page 98 and 99:

Plane Polygons 81 QUESTIONS AND PRO

- Page 100 and 101:

7Time, Percentages, and Graphs You

- Page 102 and 103:

Figure 7-2 A racecar driver can cal

- Page 104 and 105:

When a percentage expresses a chang

- Page 106 and 107:

Time, Percentages, and Graphs 89 Fi

- Page 108 and 109:

Time, Percentages, and Graphs 91 Fi

- Page 110 and 111:

5-mile track. Each graph gives you

- Page 112 and 113:

Part 2 ALGEBRA, GEOMETRY, AND TRIGO

- Page 114 and 115:

8First Notions in Algebra As proble

- Page 116 and 117:

First Notions in Algebra 99 Figure

- Page 118 and 119:

First Notions in Algebra 101 Figure

- Page 120 and 121:

First Notions in Algebra 103 (a b)

- Page 122 and 123:

To recap, here are the rules if you

- Page 124 and 125:

First Notions in Algebra 107 Figure

- Page 126 and 127:

First Notions in Algebra 109 Figure

- Page 128 and 129:

4. Suppose x 5 and y 7. Then what

- Page 130 and 131:

9Some “School” Algebra In this

- Page 132 and 133:

Some “School” Algebra 115 DIMEN

- Page 134 and 135:

Some “School” Algebra 117 4 u

- Page 136 and 137:

Some “School” Algebra 119 20x

- Page 138 and 139:

Some “School” Algebra 121 Figur

- Page 140 and 141:

Figure 9-9 Sometimes it’s easier

- Page 142 and 143:

9. Adding 1 to the numerator and de

- Page 144 and 145:

10Quadratic Equations Simultaneous

- Page 146 and 147:

Quadratic Equations 129 Figure 10-3

- Page 148 and 149:

Quadratic Equations 131 Figure 10-5

- Page 150 and 151:

Quadratic Equations 133 Figure 10-8

- Page 152 and 153:

Quadratic Equations 135 Figure 10-1

- Page 154 and 155:

Quadratic Equations 137 Figure 10-1

- Page 156 and 157:

What about the “negative solution

- Page 158 and 159:

11 Some Useful Shortcuts Have you n

- Page 160 and 161:

Some Useful Shortcuts 143 FINDING S

- Page 162 and 163:

used to derive square roots to seve

- Page 164 and 165:

Some Useful Shortcuts 147 Figure 11

- Page 166 and 167:

Some Useful Shortcuts 149 Figure 11

- Page 168 and 169:

Some Useful Shortcuts 151 which sim

- Page 170 and 171:

12. In each of the following pairs

- Page 172 and 173:

12 Mechanical Mathematics In this c

- Page 174 and 175:

Mechanical Mathematics 157 Figure 1

- Page 176 and 177:

is at (a times t) feet per second.

- Page 178 and 179:

Mechanical Mathematics 161 Figure 1

- Page 180 and 181:

If the mass is 1 kg, the force is 9

- Page 182 and 183:

Mechanical Mathematics 165 Figure 1

- Page 184 and 185:

Mechanical Mathematics 167 Figure 1

- Page 186 and 187:

Mechanical Mathematics 169 Figure 1

- Page 188 and 189:

Mechanical Mathematics 171 Figure 1

- Page 190 and 191:

13 Ratio and Proportion Thus far, t

- Page 192 and 193:

Ratio and Proportion 175 PROPORTION

- Page 194 and 195:

In any triangle, its three interior

- Page 196 and 197:

Ratio and Proportion 179 Figure 13-

- Page 198 and 199:

Ratio and Proportion 181 Figure 13-

- Page 200 and 201:

Ratio and Proportion 183 Figure 13-

- Page 202 and 203:

Ratio and Proportion 185 Figure 13-

- Page 204 and 205:

14 Trigonometric and Geometric Calc

- Page 206 and 207:

Trigonometric and Geometric Calcula

- Page 208 and 209:

Trigonometric and Geometric Calcula

- Page 210 and 211:

Trigonometric and Geometric Calcula

- Page 212 and 213:

PROPERTIES OF THE ISOSCELES TRIANGL

- Page 214 and 215:

Suppose you name the equal pairs of

- Page 216 and 217:

Trigonometric and Geometric Calcula

- Page 218 and 219:

Copyright © 2008, 1999 by The McGr

- Page 220 and 221:

15 Systems of Counting The decimal

- Page 222 and 223:

Systems of Counting 205 Figure 15-2

- Page 224 and 225:

Systems of Counting 207 OCTAL NUMBE

- Page 226 and 227:

Systems of Counting 209 DECIMAL BIN

- Page 228 and 229:

Systems of Counting 211 Figure 15-6

- Page 230 and 231:

Systems of Counting 213 Figure 15-8

- Page 232 and 233:

are shortcut methods for performing

- Page 234 and 235:

1. Find the decimal equivalent of t

- Page 236 and 237:

16 Progressions, Permutations, and

- Page 238 and 239:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 240 and 241:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 242 and 243:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 244 and 245:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 246 and 247:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 248 and 249:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 250 and 251:

Progressions, Permutations, and Com

- Page 252 and 253:

17 Introduction to Derivatives The

- Page 254 and 255:

Figure 17-2 The derivative of the f

- Page 256 and 257:

is negative when x is negative, bec

- Page 258 and 259:

This rule holds true for all expres

- Page 260 and 261:

Introduction to Derivatives 243 CIR

- Page 262 and 263:

Introduction to Derivatives 245 Fig

- Page 264 and 265:

Introduction to Derivatives 247 Fig

- Page 266 and 267:

Introduction to Derivatives 249 Fig

- Page 268 and 269:

18 More about Differentiation The p

- Page 270 and 271:

More about Differentiation 253 Figu

- Page 272 and 273:

More about Differentiation 255 by t

- Page 274 and 275:

More about Differentiation 257 MULT

- Page 276 and 277:

In the powers table, 0 n is always

- Page 278 and 279:

DERIVATIVE OF FUNCTION MULTIPLIED B

- Page 280 and 281:

More about Differentiation 263 QUES

- Page 282 and 283:

19 Introduction to Integrals Now th

- Page 284 and 285:

Introduction to Integrals 267 Figur

- Page 286 and 287:

Introduction to Integrals 269 Figur

- Page 288 and 289:

(it subtracts from itself), so you

- Page 290 and 291:

Introduction to Integrals 273 Figur

- Page 292 and 293:

Introduction to Integrals 275 VOLUM

- Page 294 and 295:

1. Find the derivatives of the prod

- Page 296 and 297:

20Combining Calculus with Other Too

- Page 298 and 299:

plotting nine points, but to get a

- Page 300 and 301:

In a situation like this, you have

- Page 302 and 303:

Combining Calculus with Other Tools

- Page 304 and 305:

Combining Calculus with Other Tools

- Page 306 and 307:

Combining Calculus with Other Tools

- Page 308 and 309:

These principal axes can be regarde

- Page 310 and 311:

e reaches 1, the ellipse “breaks

- Page 312 and 313:

Combining Calculus with Other Tools

- Page 314 and 315:

Combining Calculus with Other Tools

- Page 316 and 317:

etween the plane and the double con

- Page 318 and 319:

21Alternative Coordinate Systems Th

- Page 320 and 321:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 303

- Page 322 and 323:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 305

- Page 324 and 325:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 307

- Page 326 and 327:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 309

- Page 328 and 329:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 311

- Page 330 and 331:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 313

- Page 332 and 333:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 315

- Page 334 and 335:

perpendicular to the other two. The

- Page 336 and 337:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 319

- Page 338 and 339:

Alternative Coordinate Systems 321

- Page 340 and 341:

22Complex Numbers Long ago, humanki

- Page 342 and 343:

Multiplying repeatedly by i works t

- Page 344 and 345:

Complex Numbers 327 Figure 22-4 The

- Page 346 and 347:

Complex Numbers 329 When you cube i

- Page 348 and 349:

Complex Numbers 331 Figure 22-9 The

- Page 350 and 351:

Complex Numbers 333 Figure 22-11 At

- Page 352 and 353:

Complex Numbers 335 QUESTIONS AND P

- Page 354 and 355:

Part 4 TOOLS OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS

- Page 356 and 357:

23Trigonometry in the Real World Tr

- Page 358 and 359:

The absolute accuracy (in fixed uni

- Page 360 and 361:

Trigonometry in the Real World 343

- Page 362 and 363:

objects, even when they are observe

- Page 364 and 365:

Trigonometry in the Real World 347

- Page 366 and 367:

Trigonometry in the Real World 349

- Page 368 and 369:

Trigonometry in the Real World 351

- Page 370 and 371:

Trigonometry in the Real World 353

- Page 372 and 373:

Now find the distance PV by applyin

- Page 374 and 375:

7. What is the range of the aircraf

- Page 376 and 377:

24Logarithms and Exponentials A log

- Page 378 and 379:

Logarithms and Exponentials 361 Fig

- Page 380 and 381:

Logarithms and Exponentials 363 Fig

- Page 382 and 383:

Now try an example in which neither

- Page 384 and 385:

Let’s put a number into this form

- Page 386 and 387:

Logarithms and Exponentials 369 10

- Page 388 and 389:

Logarithms and Exponentials 371 Fig

- Page 390 and 391:

Suppose x is some real number. The

- Page 392 and 393:

To demonstrate this, let b e, x 2

- Page 394 and 395:

“Inv” key followed by a “ln

- Page 396 and 397:

and so on. A decrease of 1 order of

- Page 398 and 399:

25Scientific Notation Tutorial In s

- Page 400 and 401:

Another alternative multiplication

- Page 402 and 403:

line that covers 3 orders of magnit

- Page 404 and 405:

Scientific Notation Tutorial 387 (3

- Page 406 and 407:

Scientific Notation Tutorial 389 (5

- Page 408 and 409:

equality symbols. It is universally

- Page 410 and 411:

Sometimes, the outcome of determini

- Page 412 and 413:

26Vectors You’ve already seen a f

- Page 414 and 415:

Vectors 397 MULTIPLICATION OF A VEC

- Page 416 and 417:

Vectors 399 The values of the angle

- Page 418 and 419:

Vectors 401 If a is multiplied by a

- Page 420 and 421:

Vectors 403 Figure 26-5 Direction a

- Page 422 and 423:

Vectors 405 This formula works in a

- Page 424 and 425:

Vectors 407 You are told that these

- Page 426 and 427:

Vectors 409 4. Consider the two vec

- Page 428 and 429:

27Logic and Truth Tables To gain a

- Page 430 and 431:

are true. If any one of the compone

- Page 432 and 433:

antecedent is (P & C). The “impli

- Page 434 and 435:

Logic and Truth Tables 417 X Y X &

- Page 436 and 437:

Logic and Truth Tables 419 (X 1 Y)

- Page 438 and 439:

Logic and Truth Tables 421 The same

- Page 440 and 441:

classes—a certain way that multip

- Page 442 and 443:

Table 27-9B Derivation of truth val

- Page 444 and 445:

Logic and Truth Tables 427 A X Y X

- Page 446 and 447:

Logic and Truth Tables 429 X Y Z X

- Page 448 and 449: Logic and Truth Tables 431 X Y Z X

- Page 450 and 451: 28Beyond Three Dimensions As you ha

- Page 452 and 453: Beyond Three Dimensions 435 Figure

- Page 454 and 455: Beyond Three Dimensions 437 Figure

- Page 456 and 457: a little later! It “lives” for

- Page 458 and 459: Beyond Three Dimensions 441 IMPOSSI

- Page 460 and 461: Beyond Three Dimensions 443 Displac

- Page 462 and 463: Beyond Three Dimensions 445 Figure

- Page 464 and 465: Beyond Three Dimensions 447 Figure

- Page 466 and 467: Beyond Three Dimensions 449 NO PARA

- Page 468 and 469: such as the pyramid, cube, and sphe

- Page 470 and 471: 2. If there are no pairs of paralle

- Page 472 and 473: 29A Statistics Primer Statistics is

- Page 474 and 475: A Statistics Primer 457 Figure 29-2

- Page 476 and 477: A Statistics Primer 459 PARAMETER A

- Page 478 and 479: A Statistics Primer 461 Figure 29-4

- Page 480 and 481: A Statistics Primer 463 of dice, th

- Page 482 and 483: A Statistics Primer 465 Figure 29-6

- Page 484 and 485: To determine µ sc , check the tabl

- Page 486 and 487: A Statistics Primer 469 Figure 29-6

- Page 488 and 489: A Statistics Primer 471 making it m

- Page 490 and 491: 30Probability Basics Probability is

- Page 492 and 493: Probability Basics 475 Event 1 Even

- Page 494 and 495: Probability Basics 477 As with math

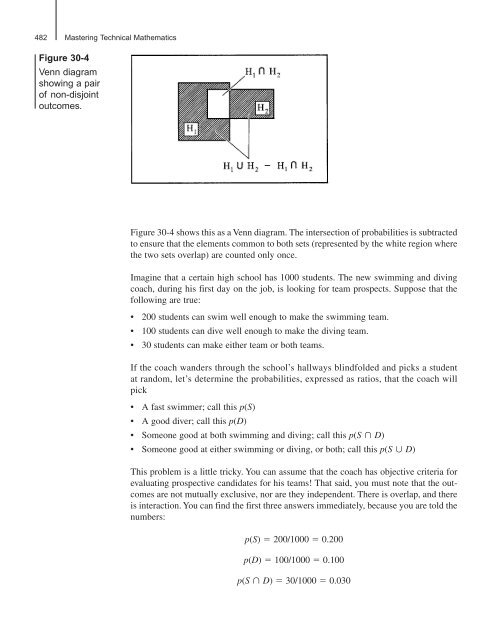

- Page 496 and 497: Probability Basics 479 that both co

- Page 500 and 501: Probability Basics 483 To calculate

- Page 502 and 503: Probability Basics 485 • 30 peopl

- Page 504 and 505: Probability Basics 487 The resultin

- Page 506 and 507: Probability Basics 489 Because the

- Page 508 and 509: Probability Basics 491 Figure 30-11

- Page 510 and 511: Probability Basics 493 views are re

- Page 512 and 513: Final Exam Do not refer to the text

- Page 514 and 515: Final Exam 497 (a) An even number t

- Page 516 and 517: Final Exam 499 X Y Z ? F F F F F F

- Page 518 and 519: Final Exam 501 (c) A harmonic progr

- Page 520 and 521: Final Exam 503 (c) 1.8 10 6 km (d)

- Page 522 and 523: Final Exam 505 47. Suppose an item

- Page 524 and 525: Final Exam 507 Figure E-6 Illustrat

- Page 526 and 527: Final Exam 509 (a) p q (b) p q 1

- Page 528 and 529: Final Exam 511 (d) Roots of w (e) P

- Page 530 and 531: Final Exam 513 82. Which of the fol

- Page 532 and 533: Final Exam 515 (b) It decreases in

- Page 534 and 535: Final Exam 517 95. In the situation

- Page 536 and 537: Appendix 1 Solutions to End-of-Chap

- Page 538 and 539: Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 540 and 541: Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 542 and 543: Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 544 and 545: Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 546 and 547: Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 548 and 549:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 550 and 551:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 552 and 553:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 554 and 555:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 556 and 557:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 558 and 559:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 560 and 561:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 562 and 563:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 564 and 565:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 566 and 567:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 568 and 569:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 570 and 571:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 572 and 573:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 574 and 575:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 576 and 577:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 578 and 579:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 580 and 581:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 582 and 583:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 584 and 585:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 586 and 587:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 588 and 589:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 590 and 591:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 592 and 593:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 594 and 595:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 596 and 597:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 598 and 599:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 600 and 601:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 602 and 603:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 604 and 605:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 606 and 607:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 608 and 609:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 610 and 611:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 612 and 613:

Figure A-30 Illustration for soluti

- Page 614 and 615:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 616 and 617:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 618 and 619:

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questio

- Page 620 and 621:

Appendix 2 Answers to Final Exam Qu

- Page 622 and 623:

Appendix 3 Table of Derivatives Let

- Page 624 and 625:

Appendix 4 Table of Indefinite Inte

- Page 626 and 627:

Table of Indefinite Integrals 609 f

- Page 628 and 629:

Table of Indefinite Integrals 611 f

- Page 630 and 631:

Table of Indefinite Integrals 613 f

- Page 632 and 633:

Suggested Additional Reading Bluman

- Page 634 and 635:

Index absolute accuracy, 341 error,

- Page 636 and 637:

cosines, law of, 347-348 counter, m

- Page 638 and 639:

geometry elliptic, 449 Euclidean, 4

- Page 640 and 641:

exponential, 369-371 frequency, 255

- Page 642 and 643:

esonance, in system, 168-170, 255 r

- Page 644:

direction angles, 402-403 direction