Influence of cavity preparation design on fracture resistance of ...

Influence of cavity preparation design on fracture resistance of ...

Influence of cavity preparation design on fracture resistance of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Influence</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> posterior<br />

Leucite-reinforced ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Carlos Jose Soares, DDS, MS, PhD, a Luis Roberto Marc<strong>on</strong>des Martins, DDS, MS, PhD, b<br />

Rodrigo Borges F<strong>on</strong>seca, DDS, MS, PhD, c Lourenco Correr-Sobrinho, DDS, MS, PhD, d<br />

and Alfredo Julio Fernandes Neto, DDS, MS, PhD e<br />

School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Dentistry, Federal University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Piracicaba School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Dentistry, State Univerty <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil<br />

Statement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> problem. C<strong>on</strong>troversy exists c<strong>on</strong>cerning the preferred <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> for posterior ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

to improve their <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> under occlusal load.<br />

Purpose. The aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study was to assess the <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> leucite-reinforced ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

placed <strong>on</strong> molars with different <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

Material and methods. Ninety n<strong>on</strong>carious molars were selected, stored in 0.2% thymol soluti<strong>on</strong>, and divided<br />

into 9 groups (n=10): IT, intact teeth; CsI, c<strong>on</strong>servative inlay; ExI, extensive inlay; CsO/mb, c<strong>on</strong>servative <strong>on</strong>lay<br />

with mesio-buccal cusp coverage; ExO/mb, entensive <strong>on</strong>lay with mesio-buccal cusp coverage; CsO/b, c<strong>on</strong>servative<br />

<strong>on</strong>lay with buccal cusp coverage; ExO/b, entensive <strong>on</strong>lay with buccal cusp coverage; CsO/t, c<strong>on</strong>servative<br />

<strong>on</strong>lay with total cusp coverage; ExO/t, extensive <strong>on</strong>lay with total cusp coverage. Teeth were restored with a<br />

Leucite-reinforced ceramic (Cergogold). The <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> (N) was assessed under compressive load in a<br />

universal testing machine. The data were analyzed with 1-way and 2-way analyses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variance, followed by<br />

the Tukey HSD test (a=.05). Fracture modes were recorded, based <strong>on</strong> the degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth structure and<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong> damage.<br />

Results. One-way analysis showed that intact teeth had the highest <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> values. Two-way analyses<br />

showed no significant differences for the isthmus extenti<strong>on</strong> factor, but showed a significant difference for the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>fracture</strong> (P=.03), and also for the interacti<strong>on</strong> between both factors (P=.013). The<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> mode observed in all groups tended to involve <strong>on</strong>ly restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>. Within the limitati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study, it was observed that cuspal coverage does not increase <strong>fracture</strong><br />

<strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the posterior tooth-restorati<strong>on</strong> complex restored with leucite-reinforced ceramics. (J Prosthet<br />

Dent 2006;95:421-9.)<br />

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS<br />

In this in vitro study, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> involving cuspal reducti<strong>on</strong> for restorati<strong>on</strong> with<br />

Leucite-reinforced ceramic did not improve the <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong>. The <strong>fracture</strong> modes<br />

observed were predominantly restricted to the restorative material.<br />

The presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> extensive carious lesi<strong>on</strong>s, unsatisfactory<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s, and tooth <strong>fracture</strong> results in c<strong>on</strong>troversy<br />

regarding the optimal restorative procedure.<br />

Choosing between use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a direct or indirect technique<br />

Presented at the IADR Meeting, Hawaii, March 10-13, 2004.<br />

Supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas<br />

Gerais (FAPEMIG), Grant 1987-03.<br />

a<br />

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor, Operative Dentistry and Dental Materials, Dental School<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Federal University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Uberlandia.<br />

b<br />

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor, Operative Dentistry, Dental School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Piracicaba, State<br />

University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Campinas.<br />

c<br />

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor, Operative Dentistry and Dental Materials, Dental School<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Federal University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Uberlandia.<br />

d<br />

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor, Dental Materials, Dental School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Piracicaba, State University<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Campinas.<br />

e<br />

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor, Prosthod<strong>on</strong>tic and Dental Materials, Dental School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Federal University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Uberlandia.<br />

when placing a posterior restorati<strong>on</strong> is difficult and involves<br />

esthetic, biomechanical, anatomical, and financial<br />

c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s. When an indirect restorati<strong>on</strong> is determined<br />

to be the best treatment opti<strong>on</strong>, the clinician must then<br />

determine the geometric c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. 1-3 Several <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have been proposed for<br />

preparing posterior resin-b<strong>on</strong>ded all-ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

4-7 due to the particular mechanical and structural<br />

characteristics presented by ceramic restorative<br />

materials. 8-10<br />

For cast metal restorati<strong>on</strong>s, n<strong>on</strong>functi<strong>on</strong>al and functi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

cusps tend to be reduced during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>,<br />

producing better stress distributi<strong>on</strong>. 11 Since<br />

metal restorati<strong>on</strong>s are generally cemented with a n<strong>on</strong>adhesive<br />

cement, such as zinc-phosphate cement, complete<br />

cusp coverage is indicated to increase dental<br />

structure <strong>resistance</strong>. 12 Tooth <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

JUNE 2006 THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY 421

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY SOARES ET AL<br />

advocated for posterior ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s have been<br />

based <strong>on</strong> traditi<strong>on</strong>al cast metal restorati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, but<br />

with more occlusal tooth reducti<strong>on</strong> and a slightly increased<br />

taper. 3 These <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s can involve the removal<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>siderable tooth structure, 13 and as more<br />

structure is removed, a tooth will have less <strong>resistance</strong><br />

to <strong>fracture</strong>. 14 However, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s for posterior ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s, some authors have dem<strong>on</strong>strated<br />

that occlusal reducti<strong>on</strong> results in a reduced chance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> restorati<strong>on</strong><br />

failure, likely increasing l<strong>on</strong>gevity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the restorati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

4,6,15 Fracture <strong>resistance</strong> tests have been used to<br />

determine the forces that may induce <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> such<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s, and thus enable a <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> to<br />

be suggested for providing greatest <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong>.<br />

10,16-26<br />

Dental ceramics are c<strong>on</strong>sidered to be esthetic restorative<br />

materials with desirable characteristics, such as<br />

translucence, fluorescence, and chemical stability. 17,27<br />

They are also biocompatible, have high compressive<br />

strength, and their thermal expansi<strong>on</strong> coefficient is similar<br />

to that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth structure. 27 In spite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their<br />

many advantages, ceramics are fragile under tensile<br />

strain, making them susceptible to <strong>fracture</strong> during the<br />

luting procedure and under occlusal force. 28-31 This<br />

dichotomy raises an important questi<strong>on</strong> as to which is<br />

the best <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> for posterior teeth<br />

restored with ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Therefore, the aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study was to assess the<br />

in vitro <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Leucite-reinforced<br />

ceramic-restored posterior teeth, and to analyze the<br />

modes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>fracture</strong> with various <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

The null hypothesis was that different <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have no effect <strong>on</strong> the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth<br />

restored with Leucite-reinforced ceramics.<br />

MATERIAL AND METHODS<br />

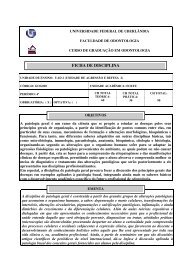

Fig. 1. Cavity <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different experimental groups.<br />

Ninety freshly extracted, sound, caries-free human<br />

mandibular molars <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> similar size and shape were<br />

selected by measuring the buccolingual and mesiodistal<br />

widths in millimeters, allowing a maximum deviati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

10% from the determined mean. Teeth were stored in<br />

0.2% thymol soluti<strong>on</strong>. Calculus and s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t-tissue deposits<br />

were removed with a hand scaler. The teeth were cleaned<br />

using a rubber cup and fine pumice water slurry and then<br />

stored in 0.9% saline soluti<strong>on</strong> at 4°C until completi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the experiment. The roots were covered with a 0.3-mm<br />

layer <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a polyether impressi<strong>on</strong> material (Impregum; 3M<br />

ESPE, St Paul, Minn) to simulate the period<strong>on</strong>tal ligament,<br />

and embedded in a polystyrene resin (Cristal,<br />

Piracicaba, Sao Paulo, Brazil) up to 2 mm below<br />

the cementoenamel juncti<strong>on</strong> to simulate the alveolar<br />

b<strong>on</strong>e. 17,24 The teeth were divided into 9 groups<br />

(n=10) as follows: IT, intact teeth (c<strong>on</strong>trol group);<br />

CsI, c<strong>on</strong>servative inlay; ExI, extensive inlay; CsO/mb,<br />

<strong>on</strong>lay with c<strong>on</strong>servative isthmus covering the mesiobuccal<br />

cusp; ExO/mb, <strong>on</strong>lay with extensive isthmus<br />

covering the mesio-buccal cusp; CsO/b, <strong>on</strong>lay with<br />

c<strong>on</strong>servative isthmus covering all buccal cusps; ExO/<br />

b, <strong>on</strong>lay with extensive isthmus covering all buccal<br />

cusps; CsO/t, <strong>on</strong>lay with c<strong>on</strong>servative isthmus covering<br />

all cusps; ExO/t, <strong>on</strong>lay with extensive isthmus covering<br />

all cusps (Fig. 1).<br />

Using a 6-degree taper diam<strong>on</strong>d rotary cutting<br />

instrument (3131; KG Sorensen, Barueri, Sao Paulo,<br />

Brazil), 8 different <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s, with internal rounded<br />

angles, were defined. A <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> machine (Federal<br />

University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Uberlandia, Uberlandia, Minas Gerais,<br />

Brazil) was used to standardize <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> dimensi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(Fig. 2). 17 This device c<strong>on</strong>sists <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a high-speed handpiece<br />

(KaVodo Brasil Ltd, Joinville, SC, Brazil) coupled to a<br />

mobile base. The mobile base moves vertically and horiz<strong>on</strong>tally<br />

with the aid <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 micrometers (Mitutoyo,<br />

Tokyo, Japan) with a 0.1-mm level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> accuracy. The isthmus<br />

floor <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the mesio-occluso-distal (MOD) cavities<br />

was prepared following principles for ceramic and indirect<br />

composite resin <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s. 32 The pulpal floor<br />

was prepared to a depth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2.5 mm from the occlusal<br />

422 VOLUME 95 NUMBER 6

SOARES ET AL<br />

Fig. 2. Cavity <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> instrument. (A) Micrometer c<strong>on</strong>trols<br />

quantity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vertical movement, which is moved by c<strong>on</strong>necting<br />

rod, B; (C) metal device allows 180-degree<br />

movement around its l<strong>on</strong>gitudinal axis and 360-degree movement<br />

around its transverse axis; (D) high-speed handpiece<br />

with diam<strong>on</strong>d rotary cutting instrument; (E) specimen being<br />

prepared; (F) micrometer.<br />

cavosurface margin <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>; the occlusal<br />

isthmus was 5 mm wide for extensive isthmus groups<br />

and 2.5 mm wide for c<strong>on</strong>servative isthmus groups.<br />

The buccolingual widths <strong>on</strong> mesial and distal boxes<br />

were similar to the occlusal isthmus width. Each box<br />

had a gingival floor depth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1.5 mm mesiodistally and<br />

an axial wall height <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 mm. Margins were prepared<br />

with 90-degree cavosurface angles.<br />

A single-stage impressi<strong>on</strong> was made <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each prepared<br />

tooth using a double-viscosity vinyl polysiloxane<br />

(Panasil; Kettenbach GmbH, Eschenburg, Germany)<br />

in a stock plastic tray (Tigre, Sao Paulo, Brazil).<br />

After 2 hours, the impressi<strong>on</strong>s were poured with<br />

Type IV st<strong>on</strong>e (Velmix; Kerr Italia SpA, Scafati,<br />

Italy). One technician fabricated all restorati<strong>on</strong>s using<br />

a standardized technique and following the manufacturer’s<br />

instructi<strong>on</strong>s. 27 Restorati<strong>on</strong>s were made with a<br />

leucite-reinforced ceramic (Cergogold; Degussa Dental,<br />

Hanau, Germany). A spacer (Isolit; Degussa Dental)<br />

was applied over the high-density st<strong>on</strong>e dies, and a<br />

0.7-mm-thick wax coping (Plastodent; Degussa<br />

Dental) was fabricated. The wax coping was invested<br />

(Cerg<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>it Investment; Degussa Dental) and placed in<br />

a burnout furnace (F1800 1P; EDG, Sao Paulo,<br />

Brazil) to eliminate the wax. The burnout furnace<br />

was preheated to 270°C, and the temperature was<br />

gradually increased to approximately 850°C for 40<br />

minutes with the alumina plunger kept inside the<br />

furnace. Ingots (Cergogold, shade A3; Degussa Dental)<br />

were pressed in an automatic press furnace (Cerampress<br />

Qex; Dentsply Ceramco, York, Pa). After cooling,<br />

the specimens were divested using 50-mm glass<br />

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

Fig. 3. Compressive loading using 6-mm-diameter steel<br />

sphere placed in center <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occlusal leucite-reinforced<br />

ceramic molar restorati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

beads at 4-bar pressure, followed by airborne-particle<br />

abrasi<strong>on</strong> with 100-mm aluminum oxide at 2-bar pressure<br />

to remove the refractory material. Finally, the<br />

specimens were treated with 100-mm aluminum oxide<br />

airborne-particle abrasi<strong>on</strong> at 1-bar pressure.<br />

The ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s were then luted (RelyX<br />

ARC; 3M ESPE), following the manufacturer’s instructi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Ceramic inlays were etched with 10% hydr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>luoric<br />

acid (C<strong>on</strong>dici<strong>on</strong>ador de Porcelanas; Dentsply, Sao<br />

Paulo, Brazil) for 60 sec<strong>on</strong>ds, and then a silane agent<br />

(Rely-X ceramic primer; 3M ESPE) was applied for<br />

60 sec<strong>on</strong>ds and dried. 27 The <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s (enamel<br />

and dentin) were etched using 37% phosphoric acid for<br />

15 sec<strong>on</strong>ds, rinsed, and blotted dry with absorbent paper.<br />

With a fully saturated brush tip, 2 c<strong>on</strong>secutive coats<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an adhesive system (Adper Single B<strong>on</strong>d; 3M ESPE)<br />

were applied to the tooth, gently dried for 5 sec<strong>on</strong>ds<br />

with compressed air, and polymerized with a halogen<br />

light-polymerizati<strong>on</strong> unit (XL 3000; 3M ESPE) for 20<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>ds at an intensity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 800 mW/cm 2 and a sourceto-specimen<br />

distance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 cm. The resin luting agent was<br />

dispensed <strong>on</strong>to a mixing pad and mixed for 10 sec<strong>on</strong>ds.<br />

A thin layer <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the material was applied to the ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>, which was seated in place. Excess luting<br />

agent was removed with a brush. The luting agent was<br />

polymerized (800 mw/cm 2 , XL 3000; 3M ESPE)<br />

from the facial, lingual, and occlusal directi<strong>on</strong>s for 40<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>ds in each directi<strong>on</strong>. Finishing rotary cutting instruments<br />

(#2135 F and #2135 FF; KG Sorensen)<br />

were used to remove excess luting agent.<br />

The teeth were subjected to axial compressive loading<br />

with a metal sphere 6 mm in diameter (Fig. 3) at a crosshead<br />

speed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 0.5 mm/min in a universal testing<br />

machine (Model DL2000; EMIC, Sao Jose dos Pinhais,<br />

Brazil). The force required (N) to cause <strong>fracture</strong> was<br />

JUNE 2006 423

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY SOARES ET AL<br />

Fig. 4. Fracture modes: (I) isolated <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> restorati<strong>on</strong>; (II) restorati<strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong>s involving small porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth; (III) <strong>fracture</strong><br />

involving more than half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth, without root involvement; (IV) <strong>fracture</strong> with root involvement.<br />

Table I. One-way ANOVA <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mechanical compressi<strong>on</strong> test<br />

values<br />

Source<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variati<strong>on</strong> df<br />

Sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

squares<br />

Mean<br />

square<br />

Calculated<br />

F P<br />

Critical<br />

F<br />

Types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

8 184925.4 23115.7 11.444 .001 2.055<br />

Error 81 163606.9 2019.8<br />

Total 89 348532.2<br />

Variati<strong>on</strong> coefficient = 199.76.<br />

Table III. Two-way ANOVA (4 3 2) for mechanical<br />

compressi<strong>on</strong> test <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ceramic restored groups<br />

Source <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variati<strong>on</strong> df<br />

Sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

squares<br />

Mean<br />

square<br />

Calculated<br />

F P<br />

Type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 49541.5 16513.8 9.454 .003<br />

Buccolingual extent 1 899.8 899.8 0.515 .095<br />

Interacti<strong>on</strong> 3 22482.3 7494.1 4.290 .013<br />

Treatments 7 72923.6 10417.7<br />

Error 72 125770.7 1746.8<br />

Total 79<br />

Variati<strong>on</strong> coefficient 196.8; significant difference P,.05.<br />

recorded by a 5-kN load cell hardwired to s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tware<br />

(TESC; EMIC), which was able to detect any sudden<br />

load drop during compressi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

The <strong>fracture</strong>d specimens were evaluated to determine<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> patterns using a modified classificati<strong>on</strong> system<br />

based <strong>on</strong> the classificati<strong>on</strong> system proposed by Burke<br />

et al 8 : (I) isolated <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the restorati<strong>on</strong>; (II) restorati<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>fracture</strong> involving a small tooth porti<strong>on</strong>; (III)<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> involving more than half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth, without<br />

period<strong>on</strong>tal involvement; and (IV) <strong>fracture</strong> with period<strong>on</strong>tal<br />

involvement (Fig. 4).<br />

Table II. Mean <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> values (SDs) and statistical<br />

categories <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all experimental groups (n=10)<br />

Groups Failure load mean (N)<br />

Statistical Tukey<br />

category<br />

IT 3143.1 (635.5) A<br />

CsI 2465.4 (318.7) B<br />

ExI 2278.1 (586.4) B<br />

ExO/b 2204.5 (353.0) BC<br />

CsO/b 2158.4 (321.7) BCD<br />

CsO/t 2062.3 (488.4) BCD<br />

ExO/mb 2001.5 (337.3) BCD<br />

CsO/mb 1612.2 (349.1) CD<br />

ExO/t 1551.4 (443.3) D<br />

IT, Intact teeth.<br />

Minimum significant difference = 628.4; different letters indicate significant<br />

differences (P,.05).<br />

Table IV. Mean <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> (SD) values and<br />

statistical categories defined by Tukey HSD test for<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong> between isthmus extensi<strong>on</strong> and <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g> factors (n=10)<br />

Groups Failure load mean values General mean values<br />

C<strong>on</strong>servative<br />

CsI 2465.4 (318.7) A<br />

CsO/b 2158.4 (321.7) A<br />

CsO/t 2062.3 (488.4) AB<br />

CsO/mb 1612.2 (349.1) B<br />

Extensive<br />

ExI 2278.1 (586.4) a<br />

ExO/b 2204.5 (353.0) a<br />

Ex/Omb 2001.5 (337.3) ab<br />

ExO/t 1551.4 (443.3) b<br />

2074.6 (369.5) A<br />

2008.9 (430.0) A<br />

Minimum significant difference = 482.59.<br />

Different uppercase (c<strong>on</strong>servative groups) or lowercase (extensive groups)<br />

letters indicate significant differences (P,.05). General mean values are<br />

compared by uppercase letters (P..05).<br />

424 VOLUME 95 NUMBER 6

SOARES ET AL<br />

Fig. 5. Mean <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> values and distributi<strong>on</strong> by statistical categories. Different letters represent significant differences<br />

identified by Tukey test for <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s characterized by c<strong>on</strong>servative occlusal isthmus (P,.05).<br />

Fig. 6. Mean <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> values and distributi<strong>on</strong> by statistical categories. Different letters represent significant differences<br />

identified by Tukey test for <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s characterized by extensive occlusal isthmus (P,.05).<br />

In the initial analysis, the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> data <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the 9 groups were submitted to statistical analysis by<br />

1-way analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey<br />

H<strong>on</strong>estly Significant Difference (HSD) test. In the<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d analysis, the aim was to determine the influence<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 factors involved in this study, the dimensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

isthmus floor and cuspal coverage. Therefore, the data<br />

were analyzed with a 2-way ANOVA (4 3 2) and the<br />

Tukey HSD test. For all tests, groups were c<strong>on</strong>sidered<br />

statistically different at a=.05.<br />

RESULTS<br />

The 1-way ANOVA showed that there were significant<br />

differences (P=.001) am<strong>on</strong>g all groups with respect<br />

to <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> (Table I). The Tukey HSD test<br />

showed that intact teeth presented a higher <strong>resistance</strong> to<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> under occlusal load, which was significant when<br />

compared to the other groups (P,.05). The mean and<br />

SD <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the forces applied to cause failure in each tested<br />

group are shown in Table II. Two-way ANOVA showed<br />

that there were significant differences (P=.013) for the<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong> between occlusal isthmus floor dimensi<strong>on</strong><br />

and cuspal coverage procedure (Table III). The Tukey<br />

test was applied to determine the significance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the interacti<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 2 factors (Table IV) and indicated that<br />

the cuspal coverage did not result in higher <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

(Figs. 5 and 6). The <strong>fracture</strong> mode analysis indicated<br />

that all groups tended to dem<strong>on</strong>strate <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

<strong>fracture</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> restorati<strong>on</strong>s, rather than tooth structure<br />

(Fig. 7).<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

Performing in vitro experiments that aim to analyze<br />

indirect restorati<strong>on</strong> failures, characterized by the<br />

JUNE 2006 425

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY SOARES ET AL<br />

Fig. 7. Representative <strong>fracture</strong> modes observed after compressive loading test. A, Inlay. B, Onlay covering 1 cusp. C, Onlay<br />

covering all buccal cusps. D, Onlay covering all cusps.<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> either the restorative material or dental structure,<br />

is an important method for improving restorative<br />

procedures. 1,2,10,12,16,17,28 There are a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> factors<br />

that may interfere with <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong>, such<br />

as the tooth embedment method, type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> load applicati<strong>on</strong><br />

device, and crosshead speed. 8 Thus, the experimental<br />

methods used for in vitro analyses do not faithfully<br />

represent real clinical c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, in which failures occur<br />

primarily due to fatigue. 18 To minimize the discrepancy<br />

between experimental assessments and clinical failures,<br />

different methods have been used, such as the joint<br />

use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mechanical tests and <strong>fracture</strong> mode analysis according<br />

to predefined scales. 8,17,19<br />

Mechanical <strong>fracture</strong> tests are performed to numerically<br />

quantify the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> restorative material<br />

types, 2,10,16,17,19,20 luting procedures, 12,21 and <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

characteristics 14,22 for <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong><br />

when submitted to a c<strong>on</strong>centrated and increasing load.<br />

These tests usually produce failure loads that exceed<br />

the load limit exerted by normal stomatognathic system<br />

movements. 33 In spite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this fact, higher loading situati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

can be compared to the situati<strong>on</strong> in which the<br />

individual grinds a solid body <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> small dimensi<strong>on</strong>s and<br />

the force that would be distributed over the occlusal<br />

surfaces <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> posterior teeth is c<strong>on</strong>centrated over a single<br />

tooth. If this tooth is structurally debilitated or prepared<br />

with an inadequate <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the result may be<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth, the restorati<strong>on</strong>, or both.<br />

When performing mechanical tests, some factors are<br />

important to more closely approximate the clinical situati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

such as the root embedment method to simulate<br />

the period<strong>on</strong>tal membrane, the loading apparatus, and<br />

the mode <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> load transmissi<strong>on</strong>. 8 The simulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

period<strong>on</strong>tal ligament should be d<strong>on</strong>e with an elastomeric<br />

material that is able to undergo elastic deformati<strong>on</strong><br />

and reproduce the accommodati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth<br />

in the alveolus, providing the n<strong>on</strong>c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

stresses in the cervical regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth. Moreover, a<br />

simulated period<strong>on</strong>tal ligament is highly influential <strong>on</strong><br />

the <strong>fracture</strong> pattern. 23 In this experiment, a polyether<br />

impressi<strong>on</strong> material was used in associati<strong>on</strong> with a polystyrene<br />

resin as an adequate method for <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

tests. 17,24<br />

Occlusal loading is another important factor. Burke<br />

et al 8 and Burke and Watts 9 c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the best<br />

method for measuring the <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> premolars to<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> is the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a cylinder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a defined diameter. 19<br />

The use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a 6-mm steel sphere for <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong><br />

testing by Dietschi et al 25 and Soares et al 17 was shown<br />

to be ideal for molars because it c<strong>on</strong>tacts the functi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

and n<strong>on</strong>functi<strong>on</strong>al cusps in positi<strong>on</strong>s close to those<br />

found clinically.<br />

The results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the present study showed that the mean<br />

<strong>resistance</strong> to load <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> healthy teeth (IT:3143.1 6 635.5<br />

N) was significantly higher than the <strong>resistance</strong> to load<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth prepared with different types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

and restored with a Leucite-reinforced ceramic; thus,<br />

the null hypothesis was rejected. This dem<strong>on</strong>strates<br />

that the restorative process, even when adhesive techniques<br />

are associated with cuspal coverage, is not able<br />

to restore the total <strong>resistance</strong> to load <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> healthy molars.<br />

This result is in agreement with the studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Morin<br />

426 VOLUME 95 NUMBER 6

SOARES ET AL<br />

et al, 1 St-Georges et al, 26 and particularly with that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

M<strong>on</strong>delli et al, 14 who showed a reducti<strong>on</strong> in the <strong>resistance</strong><br />

to <strong>fracture</strong> for teeth that had been prepared with<br />

greater removal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dental structure. Since ceramics<br />

have high elastic moduli and tend to c<strong>on</strong>centrate stress<br />

inside the body <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the restorati<strong>on</strong>, 4,18,31 they have lower<br />

<strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> than healthy teeth, even though<br />

the ceramic is reinforced by the inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oxides. 27<br />

This is because ceramics are not capable <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> undergoing<br />

elastic deformati<strong>on</strong> at the same rate as tooth structure<br />

and resinous materials. Thus, stress c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s are<br />

dependent <strong>on</strong> the geometry <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the specimen material,<br />

loading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, and presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> intrinsic or extrinsic<br />

flaws. In additi<strong>on</strong>, the resin luting agent under a ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong> may act as a s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t layer and could reduce the<br />

effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stress c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>. In spite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the adhesive<br />

process being fundamental for luting a leucite-reinforced<br />

ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>, 12,27 the cushi<strong>on</strong>ing effect<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the resinous cement did not seem to be sufficient<br />

to absorb the stresses, which remain inside the ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong> and demand deformati<strong>on</strong>; if deformati<strong>on</strong><br />

does not exist, <strong>fracture</strong> may occur.<br />

Analyses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the different types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s in this<br />

study showed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s resulting in a greater loss<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth structure appear to decrease the <strong>resistance</strong> to<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tooth-restorati<strong>on</strong> complex. Assif et al 22<br />

analyzed the extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> for amalgam restorati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

and found that endod<strong>on</strong>tically treated teeth with a<br />

small amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> structure removed (c<strong>on</strong>servative occlusal<br />

isthmus) and total cuspal coverage produced better<br />

<strong>resistance</strong> values. The discrepancies between the results<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Assif et al 22 and the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the present study are<br />

likely due to the differences in the mechanical properties<br />

and adhesive characteristics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the respective restorative<br />

materials used. Amalgam, as a metal, can undergo elastic<br />

deformati<strong>on</strong>; however, ceramics cannot due to their<br />

i<strong>on</strong>ic and covalent b<strong>on</strong>ds. Moreover, amalgam adhesi<strong>on</strong><br />

to the tooth structure is minimal; thus, extensive amalgam<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s demand cuspal coverage to protect<br />

teeth from <strong>fracture</strong> when the restorative material is undergoing<br />

deformati<strong>on</strong>. Ceramics, in general, present a<br />

high elastic modulus and low strain capacity, so the<br />

stress tends to c<strong>on</strong>centrate inside the material since<br />

stress can not be relieved by deformati<strong>on</strong> the material<br />

<strong>fracture</strong>s before stresses are transferred to the tooth.<br />

Leucite-reinforced ceramics have good adhesi<strong>on</strong> to<br />

tooth structures, and according to St-Georges et al, 26<br />

this enables an internal rather than an external splinting<br />

with cuspal coverage 10 to be created in some instances.<br />

Thus, the adhesive strength should be enough to support<br />

cusp deflecti<strong>on</strong>. With respect to the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all tested groups, the c<strong>on</strong>servative inlay<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> showed the highest numerical value<br />

(2465.4 6 318.7 N), but was statistically similar to<br />

the extensive inlay group, in which a greater amount<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth structure had been removed during <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

(2278.1 6 586.4 N). The ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong> presented<br />

less <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> when more tooth structure was<br />

removed during <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, and the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cuspal<br />

coverage was not a benefit.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> to discussing <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> values, it<br />

may be important to analyze the <strong>fracture</strong> modes in each<br />

experimental group. For all groups, <strong>fracture</strong> was observed<br />

in the restorati<strong>on</strong> itself. Similar findings were<br />

reported by Soares et al 17 when the authors tested feldspathic<br />

ceramic in extensive inlays, and also by Burke, 21<br />

who affirmed that the ceramic <strong>fracture</strong>s before the<br />

tooth. For the CsI group, it was found that the majority<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>fracture</strong>s occurred exclusively in the restorati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

probably because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the larger volume <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dental structure<br />

in the cusps, which resulted in a greater capacity<br />

for undergoing deformati<strong>on</strong> rather than <strong>fracture</strong>.<br />

Cuspal coverage with an <strong>on</strong>lay apparently does not<br />

produce a clear benefit to the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

restored tooth, as has been shown for metal restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

11 This is related to the fact that the failure, as<br />

seen by the <strong>fracture</strong> modes, occurs almost exclusively<br />

in ceramics. If the restorati<strong>on</strong> is expected to fail irrespective<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>, then extending <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

will not change this behavior, as seen in this<br />

study.<br />

The clinician may encounter a situati<strong>on</strong> in which the<br />

tooth presents loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a cusp or <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> it.<br />

It is not advisable to establish an occlusal c<strong>on</strong>tact at the<br />

tooth-restorati<strong>on</strong> interface, due to the difference in the<br />

mechanical behavior <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 2 structures. In this situati<strong>on</strong><br />

the need for cuspal coverage must be determined.<br />

Another c<strong>on</strong>cern is the need for covering n<strong>on</strong>functi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

cusps, which may be observed by comparing the groups<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth with <strong>on</strong>lay <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s covering just the functi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

cusps (CsO/b, 2158.4 6 321.7 N and ExO/b,<br />

2204.5 6 353.0 N), and the <strong>on</strong>lay <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s with<br />

total cusp coverage (CsO/t, 2062.3 6 488.4 N and<br />

ExO/t, 1551.4 6 443.3 N). According to the results<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study, it appears that there is no advantage in<br />

covering n<strong>on</strong>functi<strong>on</strong>al cusps.<br />

The comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the behavior <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> groups with great<br />

volumes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ceramic in occlusal isthmus (CsO/t and<br />

ExO/t) requires discussi<strong>on</strong>. In spite <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> being statistically<br />

similar, ExO/t was almost 500 N less resistant than<br />

CsO/t, and it may be that the volume <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ceramic material<br />

in the occlusal box and the thickness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> remaining tooth<br />

structure in prepared cusps are resp<strong>on</strong>sible for this finding.<br />

Ceramic thickness, when either very thin or very<br />

thick, seems to be detrimental with regard to <strong>fracture</strong>. 34<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong>, sharp angles and knife-edge–prepared<br />

cusps tend to c<strong>on</strong>centrate stress, resulting in greater susceptibility<br />

to ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong> 32 ; therefore,<br />

rounded internal angles are preferred for ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

When tooth structure loss results in an extensive<br />

occlusal isthmus, this may necessitate coverage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all the<br />

cusps, a feasible alternative for restorati<strong>on</strong> in the occlusal<br />

JUNE 2006 427

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY SOARES ET AL<br />

isthmus and also to eliminate the knife-edge form in<br />

the prepared cusps. However, further investigati<strong>on</strong> is<br />

needed to determine the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this procedure.<br />

This study has several limitati<strong>on</strong>s. The compressive<br />

load applied to the restored tooth was increased until<br />

failure; however, dental ceramics typically fail as a result<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> many loading cycles or from an accumulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> damage<br />

from stress and water. 35 In terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> in vivo loading,<br />

the masticatory cycle c<strong>on</strong>sists <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vertical<br />

and lateral forces, subjecting the ceramic to a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f-axis loading forces. 36 Cyclic loading may be more<br />

adequate to reproduce fatigue failures verified clinically.<br />

Future analyses should involve both methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> load applicati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Destructive tests are important for predicting<br />

and comparing the behavior <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a restored tooth under<br />

specific situati<strong>on</strong>s; however, future studies should perhaps<br />

use n<strong>on</strong>destructive methodologies such as finite element<br />

analysis or structural deformati<strong>on</strong> by employment<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> strain gauges, enabling not <strong>on</strong>ly analysis at the moment<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> failure but also the possible causes for the failure.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong>, because <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e material type was used in<br />

the current study, it is not possible to apply these results<br />

to other esthetic materials. 17 The results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study<br />

suggest guidelines when preparing teeth for ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s, but more analyses are required before extrapolating<br />

these results to other ceramic restorative<br />

systems.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Within the limitati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this in vitro study, the following<br />

c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s were drawn:<br />

1. Intact teeth are more resistant to <strong>fracture</strong> than teeth<br />

prepared and restored with Leucite-reinforced ceramics,<br />

irrespective <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

2. Specific <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s facilitate the<br />

occurrence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>fracture</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s, with<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> modes generally restricted to the restorati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

3. The cuspal coverage did not increase <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the posterior tooth-restorati<strong>on</strong> complex<br />

restored with Leucite-reinforced ceramics.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Morin D, Del<strong>on</strong>g R, Douglas WH. Cusp reinforcement by acid-etch technique.<br />

J Dent Res 1984;63:1075-8.<br />

2. Steele A, Johns<strong>on</strong> BR. In vitro <strong>fracture</strong> strength <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> endod<strong>on</strong>tically treated<br />

premolars. J Endod 1999;25:6-8.<br />

3. Etemadi S, Smales RJ, Drumm<strong>on</strong>d PW, Goodhart JR. Assessment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tooth<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s for posterior resin-b<strong>on</strong>ded porcelain restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

J Oral Rehabil 1999;26:691-7.<br />

4. Banks RG. C<strong>on</strong>servative posterior ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s: a literature<br />

review. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:619-26.<br />

5. Broders<strong>on</strong> SP. Complete-crown and partial-coverage tooth <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>design</str<strong>on</strong>g>s for b<strong>on</strong>ded cast ceramic restorati<strong>on</strong>s. Quintessence Int 1994;25:<br />

535-9.<br />

6. Garber DA, Goldstein RE. Porcelain and composite inlays and <strong>on</strong>lays.<br />

Esthetic posterior restorati<strong>on</strong>s. 1st ed. Chicago: Quintessence; 1994. p. 38.<br />

7. Milleding P, Ortengren M, Karlss<strong>on</strong> S. Ceramic inlay systems: some clinical<br />

aspects. J Oral Rehabil 1995;22:571-80.<br />

8. Burke FJ, Wils<strong>on</strong> NH, Watts DC. The effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> wall taper <strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong><br />

<strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth restored with resin composite inlays. Oper Dent 1993;<br />

18:230-6.<br />

9. Burke FJ, Watts DC. Fracture <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth restored with dentinb<strong>on</strong>ded<br />

crowns. Quintessence Int 1994;25:335-40.<br />

10. Bremer BD, Geurtsen W. Molar <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> after adhesive restorati<strong>on</strong><br />

with ceramic inlays or resin-based composites. Am J Dent 2001;14:<br />

216-20.<br />

11. Reeh ES, Douglas WH, Messer HH. Stiffness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> endod<strong>on</strong>tically-treated<br />

teeth related to restorati<strong>on</strong> technique. J Dent Res 1989;68:1540-4.<br />

12. Eakle WS, Staninec M. Effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b<strong>on</strong>ded gold inlays <strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth. Quintessence Int 1992;23:421-5.<br />

13. Moscovich H, Creugers NH, Jansen JA, Wolke JG. Loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sound tooth<br />

structure when replacing amalgam restorati<strong>on</strong>s by adhesive inlays. Oper<br />

Dent 1998;23:327-31.<br />

14. M<strong>on</strong>delli J, Steagall L, Ishikiriama A, de Lima Navarro MF, Soares FB.<br />

Fracture strength <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human teeth with <str<strong>on</strong>g>cavity</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>preparati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s. J Prosthet<br />

Dent 1980;43:419-22.<br />

15. Fuzzi M, B<strong>on</strong>figlioli R, Difebo G, Marin C, Caldari R, T<strong>on</strong>elli MP. Posterior<br />

porcelain inlay: clinical procedures and laboratory technique. Int J Period<strong>on</strong>tics<br />

Restorative Dent 1989;9:274-87.<br />

16. Neiva G, Yaman P, Dennis<strong>on</strong> JB, Razzoog ME, Lang BR. Resistance to<br />

<strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three all-ceramic systems. J Esthet Dent 1998;10:60-6.<br />

17. Soares CJ, Martins LRM, Pfeifer JM, Giannini M. Fracture <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

teeth restored with indirect-composite and ceramic inlay systems. Quintessence<br />

Int 2004;35:281-6.<br />

18. H<strong>on</strong>drum SO. A review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the strength properties <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dental ceramics.<br />

J Prosthet Dent 1992;67:859-65.<br />

19. Mak M, Qualtrough AJE, Burke FJ. The effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different ceramic materials<br />

<strong>on</strong> the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dentin-b<strong>on</strong>ded crowns. Quintessence<br />

Int 1997;28:197-203.<br />

20. Cotert HS, Sen BH, Balkan M. In vitro comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cuspal <strong>fracture</strong><br />

<strong>resistance</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> posterior teeth restored with various adhesive restorati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Int J Prosthod<strong>on</strong>t 2001;14:374-8.<br />

21. Burke FJ. The effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variati<strong>on</strong>s in b<strong>on</strong>ding procedure <strong>on</strong> <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dentin-b<strong>on</strong>ded all-ceramic crowns. Quintessence Int 1995;26:293-300.<br />

22. Assif D, Nissan J, Gafni Y, Gord<strong>on</strong> M. Assessment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> endod<strong>on</strong>tically treated molars restored with amalgam. J Prosthet<br />

Dent 2003;89:462-5.<br />

23. Salis SG, Hood JÁ, Stokes NA, Kirk EE. Patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> indirect <strong>fracture</strong> in<br />

intact and restored human premolar teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987;3:<br />

10-4.<br />

24. Behr M, Rosentritt M, Leibrock A, Schneider-Feyrer S, Handel G. In-vitro<br />

study <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>fracture</strong> strength and marginal adaptati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fiber-reinforced<br />

adhesive fixed partial inlay dentures. J Dent 1999;27:163-8.<br />

25. Dietschi D, Maeser M, Meyer JM, Holz J. In vitro <strong>resistance</strong> to <strong>fracture</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

porcelain inlays b<strong>on</strong>ded to tooth. Quintessence Int 1990;21:823-31.<br />

26. St-Georges AJ, Sturdevant JR, Swift EJ Jr, Thomps<strong>on</strong> JY. Fracture <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> prepared teeth restored with b<strong>on</strong>ded inlay restorati<strong>on</strong>s. J Prosthet Dent<br />

2003;89:551-7.<br />

27. Borges GA, Sophr AM, de Goes MF, Sobrinho LC, Chan DC. Effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

etching and airborne particle abrasi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the microstructure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different<br />

dental ceramics. J Prosthet Dent 2003;89:479-88.<br />

28. McLean JW, Hughes TH. The reinforcement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dental porcelain with<br />

ceramic oxides. Br Dent J 1965;119:251-67.<br />

29. J<strong>on</strong>es DW. Development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dental ceramics. An historical perspective.<br />

Dent Clin North Am 1985;29:621-44.<br />

30. van Noort R. Introducti<strong>on</strong> to dental materials. 1st ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby;<br />

1994. p. 201-14.<br />

31. Kelly JR, Nishimura I, Campbell SD. Ceramics in dentistry: historical roots<br />

and current perspectives. J Prosthet Dent 1986;75:18-32.<br />

32. McD<strong>on</strong>ald A. Preparati<strong>on</strong> guidelines for full and partial coverage ceramic<br />

restorati<strong>on</strong>s. Dent Update 2001;28:84-90.<br />

33. Gibbs CH, Mahan PE, Mauderli A, Lundeen HC, Walsh EK. Limits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human<br />

bite strength. J Prosthet Dent 1986;56:226-9.<br />

34. Scherrer SS, de Rijk WG, Belser UC, Meyer JM. Effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cement film<br />

thickness <strong>on</strong> the <strong>fracture</strong> <strong>resistance</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a machinable glass-ceramic. Dent<br />

Mater 1994;3:172-7.<br />

35. Jung YG, Peters<strong>on</strong> IM, Kim DK, Lawn BR. Lifetime-limiting strength<br />

degradati<strong>on</strong> from c<strong>on</strong>tact fatigue in dental ceramics. J Dent Res 2000;79:<br />

722-31.<br />

36. Pallis K, Griggs JA, Woody RD, Guillen GE, Miller AW. Fracture <strong>resistance</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three all-ceramic restorative systems for posterior applicati<strong>on</strong>s. J Prosthet<br />

Dent 2004;91:561-9.<br />

428 VOLUME 95 NUMBER 6

SOARES ET AL<br />

Reprint requests to:<br />

DR CARLOS JOSE SOARES<br />

FACULDADE DE ODONTOLOGIA<br />

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA<br />

AV. PARÁ, N.1720, BLOCO 2B, SALA 24<br />

CAMPUS UMUARAMA<br />

CEP: 38400-902<br />

UBERLÂNDIA, MINAS GERAIS, BRAZIL<br />

FAX: 55 34 32182279<br />

E-MAIL: carlosjsoares@umuarama.ufu.br<br />

Noteworthy Abstracts<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Current Literature<br />

0022-3913/$32.00<br />

Copyright Ó 2006 by The Editorial Council <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> The Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Prosthetic<br />

Dentistry.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.03.022<br />

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

A c<strong>on</strong>focal microscopic evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resin-dentin interface using<br />

adhesive systems with three different solvents b<strong>on</strong>ded to dry and<br />

moist dentin—An in vitro study<br />

Mohan B, Kandaswamy D. Quintessence Int 2005;36:511-21.<br />

Objective: Total dehydrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acid-etched dentin is known to cause the collapse <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> collagen fiber, which leads<br />

to poor hybridizati<strong>on</strong>. Dentin-b<strong>on</strong>ding systems with water as a solvent are found to rehydrate the collapsed<br />

collagen. Acet<strong>on</strong>e-based adhesives are found to compete with moisture, and the acet<strong>on</strong>e carries the resin<br />

deep into the dentin. The questi<strong>on</strong> arises whether to dry the dentin and use a water-based adhesive, or to<br />

keep the dentin moist and use an acet<strong>on</strong>e- or alcohol-based adhesive. The aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study was to compare<br />

different b<strong>on</strong>ding systems and techniques to assess which is most successful. A c<strong>on</strong>focal microscope was<br />

used to evaluate the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hybrid layer formati<strong>on</strong> and the depth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resin tag formati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Method and Materials: Superficial occlusal dentin specimens from 120 n<strong>on</strong>carious, freshly extracted human<br />

premolars were used for the study. The dentin was etched using 36% phosphoric acid for 15 sec<strong>on</strong>ds and then<br />

rinsed. The specimens were then randomly divided into 4 groups for different drying procedures; group I:<br />

air-dried for 30 sec<strong>on</strong>ds; group II: air-dried for 3 sec<strong>on</strong>ds; group III: blotted dry; group IV: overwet.<br />

The specimens were further subdivided into 3 groups to be tested with different b<strong>on</strong>ding systems: subgroup<br />

A: acet<strong>on</strong>e-based adhesive (Prime & B<strong>on</strong>d NT); subgroup B: water-based adhesive (Syntac Single<br />

Comp<strong>on</strong>ent); subgroup C: water- and ethanol-based adhesive (Single B<strong>on</strong>d). The resulting resin-dentin<br />

interfaces were then examined and categorized via c<strong>on</strong>focal microscopy, and relative values were assigned to<br />

each specimen.<br />

Results: Group IV (overwet) showed the lowest values, and the highest values were obtained in group III. The<br />

highest values were seen in group III, subgroup A (blotted dry, acet<strong>on</strong>e-based b<strong>on</strong>ding agent, Prime & B<strong>on</strong>d<br />

NT).<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>: Under these c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, using these three b<strong>on</strong>ding systems, maximum hybridizati<strong>on</strong> and resin<br />

tag formati<strong>on</strong> were achieved using acet<strong>on</strong>e-based adhesive <strong>on</strong> etched dentin kept moist by blot drying.—<br />

Reprinted with permissi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quintessence Publishing.<br />

JUNE 2006 429