DPCA2-2_issue

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

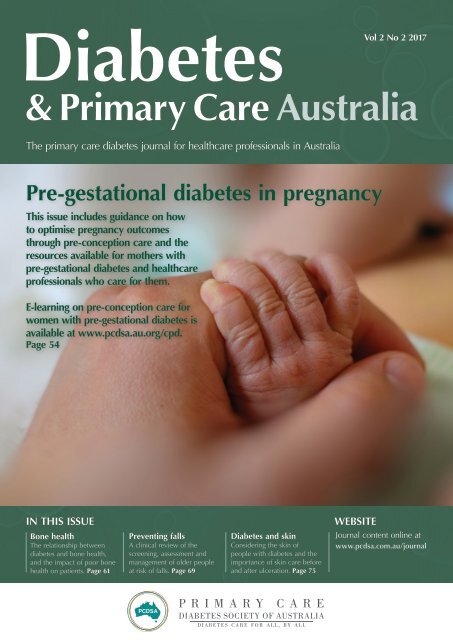

Diabetes<br />

& Primary Care Australia<br />

Vol 2 No 2 2017<br />

The primary care diabetes journal for healthcare professionals in Australia<br />

Pre-gestational diabetes in pregnancy<br />

This <strong>issue</strong> includes guidance on how<br />

to optimise pregnancy outcomes<br />

through pre-conception care and the<br />

resources available for mothers with<br />

pre-gestational diabetes and healthcare<br />

professionals who care for them.<br />

E-learning on pre-conception care for<br />

women with pre-gestational diabetes is<br />

available at www.pcdsa.au.org/cpd.<br />

Page 54<br />

IN THIS ISSUE<br />

Bone health<br />

The relationship between<br />

diabetes and bone health,<br />

and the impact of poor bone<br />

health on patients. Page 61<br />

Preventing falls<br />

A clinical review of the<br />

screening, assessment and<br />

management of older people<br />

at risk of falls. Page 69<br />

Diabetes and skin<br />

Considering the skin of<br />

people with diabetes and the<br />

importance of skin care before<br />

and after ulceration. Page 75<br />

WEBSITE<br />

Journal content online at<br />

www.pcdsa.com.au/journal

The PCDSA is a multidisciplinary society with the aim<br />

of supporting primary health care professionals to deliver<br />

high quality, clinically effective care in order to improve<br />

the lives of people with diabetes.<br />

The PCDSA will<br />

Share best practice in delivering quality diabetes care.<br />

Provide high-quality education tailored to health professional needs.<br />

Promote and participate in high quality research in diabetes.<br />

Disseminate up-to-date, evidence-based information to health<br />

professionals.<br />

Form partnerships and collaborate with other diabetes related,<br />

high level professional organisations committed to the care of<br />

people with diabetes.<br />

Promote co-ordinated and timely interdisciplinary care.<br />

Membership of the PCDSA is free and members get access to a quarterly<br />

online journal and continuing professional development activities. Our first<br />

annual conference will feature internationally and nationally regarded experts<br />

in the field of diabetes.<br />

To register, visit our website:<br />

www.pcdsa.com.au

Contents<br />

Diabetes<br />

& Primary Care Australia<br />

Volume 2 No 2 2017<br />

Website: www.pcdsa.com.au/journal<br />

Editorial<br />

Diabetes and pregnancy 45<br />

Rajna Ogrin introduces this <strong>issue</strong>, which has a focus on pregnancy and pre-conception care for women with pre-gestational diabetes.<br />

From the other side of the desktop<br />

Through diagnosis to pregnancy: My journey with diabetes 47<br />

Karen Barrett gives a first-hand perspective on her journey with diabetes and how it affected her pregnancies.<br />

CPD module<br />

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-gestational diabetes in primary health care 54<br />

Glynis Ross provides guidance to support early detection of peripheral arterial disease using evidence-based clinical tests.<br />

Articles<br />

Resources to support preconception care for women with diabetes 50<br />

Melinda Morrison, Ralph Audehm, Alison Barry and colleagues describe the resources available for health professionals and women with<br />

diabetes and provide up-to-date, evidence-based information on pregnancy and diabetes.<br />

Diabetes and bone health 61<br />

Vidhya Jahagirdar and Neil J Gittoes explore the current literature on diabetes and bone health, its impact on patients and the management<br />

strategies that may be considered in primary care to minimise risk of diabetes-related bone disease and to improve outcomes.<br />

Falls prevention in older adults with diabetes: A clinical review of screening, assessment and management recommendations 69<br />

Anna Chapman and Claudia Meyer review the screening, assessment and management recommendations for fall prevention in older people.<br />

The effect of diabetes on the skin before and after ulceration 75<br />

Roy Rasalam and Lesley Weaving look at the changes that occur in the skin of people with diabetes and the importance of skin care in<br />

relation to ulceration.<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Rajna Ogrin<br />

Senior Research Fellow, RDNS<br />

Institute, St Kilda, Vic<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Gary Kilov<br />

Practice Principal, The Seaport<br />

Practice, and Senior Lecturer,<br />

University of Tasmania,<br />

Launceston, Tas<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Ralph Audehm<br />

GP Director, Dianella Community<br />

Health, and Associate Professor,<br />

University of Melbourne,<br />

Melbourne, Vic<br />

Werner Bischof<br />

Periodontist, and Associate<br />

Professor, LaTrobe University,<br />

Bendigo, Vic<br />

Jessica Browne<br />

Senior Research Fellow, School of<br />

Psychology, Deakin University,<br />

Melbourne, Vic<br />

Anna Chapman<br />

Research Fellow, School of<br />

Primary Health Care, Monash<br />

University, Melbourne, Vic<br />

Laura Dean<br />

Course Director of the Graduate<br />

Certificate in Pharmacy<br />

Practice, Monash University, Vic<br />

Nicholas Forgione<br />

Principal, Trigg Health Care<br />

Centre, Perth, WA<br />

John Furler<br />

Principal Research Fellow and<br />

Associate Professor,<br />

University of Melbourne, Vic<br />

Mark Kennedy<br />

Medical Director, Northern Bay<br />

Health, Geelong, and Honorary<br />

Clinical Associate Professor,<br />

University of Melbourne,<br />

Melbourne, Vic<br />

Peter Lazzarini<br />

Senior Research Fellow,<br />

Queensland University of<br />

Technology, Brisbane, Qld<br />

Roy Rasalam<br />

Head of Clinical Skills and<br />

Medical Director,<br />

James Cook University, and<br />

Clinical Researcher, Townsville<br />

Hospital, Townsville, Qld<br />

Suzane Ryan<br />

Practice Principal, Newcastle<br />

Family Practice, Newcastle, NSW<br />

Editor<br />

Olivia Tamburello<br />

Editorial Manager<br />

Richard Owen<br />

Publisher<br />

Simon Breed<br />

© OmniaMed SB and the Primary Care<br />

Diabetes Society of Australia<br />

Published by OmniaMed SB,<br />

1–2 Hatfields, London<br />

SE1 9PG, UK<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this<br />

journal may be reproduced or transmitted<br />

in any form, by any means, electronic<br />

or mechanic, including photocopying,<br />

recording or any information retrieval<br />

system, without the publisher’s<br />

permission.<br />

ISSN 2397-2254<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 43

Call for papers<br />

Would you like to write an article<br />

for Diabetes & Primary Care Australia?<br />

The new journal from the Primary Care Diabetes Society of Australia<br />

To submit an article or if you have any queries, please contact: gary.kilov@pcdsa.com.au.<br />

Title page<br />

Please include the article title, the full names of the authors<br />

and their institutional affiliations, as well as full details of<br />

each author’s current appointment. This page should also have<br />

the name, address and contact telephone number(s) of the<br />

corresponding author.<br />

Article points and key words<br />

Four or five sentences of 15–20 words that summarise the major<br />

themes of the article. Please also provide four or five key words<br />

that highlight the content of the article.<br />

Abstract<br />

Approximately 150 words briefly introducing your article,<br />

outlining the discussion points and main conclusions.<br />

Introduction<br />

In 60–120 words, this should aim to draw the reader into the<br />

article as well as broadly stating what the article is about.<br />

Main body<br />

Use sub-headings liberally and apply formatting to differentiate<br />

between heading levels (you may have up to three heading levels).<br />

The article must have a conclusion, which should be succinct and<br />

logically ordered, ideally identifying gaps in present knowledge and<br />

implications for practice, as well as suggesting future initiatives.<br />

Tables and illustrations<br />

Tables and figures – particularly photographs – are encouraged<br />

wherever appropriate. Figures and tables should be numbered<br />

consecutively in the order of their first citation in the text. Present<br />

tables at the end of the articles; supply figures as logically labelled<br />

separate files. If a figure or table has been published previously,<br />

acknowledge the original source and submit written permission<br />

from the copyright holder to reproduce the material.<br />

References<br />

In the text<br />

Use the name and year (Harvard) system for references in the<br />

text, as exemplified by the following:<br />

● As Smith and Jones (2013) have shown …<br />

● As already reported (Smith and Jones, 2013) …<br />

For three or more authors, give the first author’s surname<br />

followed by et al:<br />

● As Robson et al (2015) have shown …<br />

Simultaneous references should be ordered chronologically first,<br />

and then alphabetically:<br />

● (Smith and Jones, 2013; Young, 2013; Black, 2014).<br />

Statements based on a personal communication should be<br />

indicated as such, with the name of the person and the year.<br />

In the reference list<br />

The total number of references should not exceed 30 without prior<br />

discussion with the Editor. Arrange references alphabetically first,<br />

and then chronologically. Give the surnames and initials of all<br />

authors for references with four or fewer authors; for five or more,<br />

give the first three and add “et al”. Papers accepted but not yet<br />

published may be included in the reference list as being “[In press]”.<br />

Journal article example: Robson R, Seed J, Khan E et al (2015)<br />

Diabetes in childhood. Diabetes Journal 9: 119–23<br />

Whole book example: White F, Moore B (2014) Childhood<br />

Diabetes. Academic Press, Melbourne<br />

Book chapter example: Fisher M (2012) The role of age. In: Merson<br />

A, Kriek U (eds). Diabetes in Children. 2nd edn. Academic Press,<br />

Melbourne: 15–32<br />

Document on website example: Department of Health (2009)<br />

Australian type 2 diabetes risk assessment tool (AUSDRISK).<br />

Australian Government, Canberra. Available at: http://www.<br />

health.gov.au/preventionoftype2diabetes (accessed 22.07.15)<br />

Article types<br />

Articles may fall into the categories below. All articles should be<br />

1700–2300 words in length and written with consideration of<br />

the journal’s readership (general practitioners, practice nurses,<br />

prescribing advisers and other healthcare professionals with an<br />

interest in primary care diabetes).<br />

Clinical reviews should present a balanced consideration of a<br />

particular clinical area, covering the evidence that exists. The<br />

relevance to practice should be highlighted where appropriate.<br />

Original research articles should be presented with sections<br />

for the background, aims, methods, results, discussion and<br />

conclusion. The discussion should consider the implications<br />

for practice.<br />

Clinical guideline articles should appraise newly published<br />

clinical guidelines and assess how they will sit alongside<br />

existing guidelines and impact on the management of diabetes.<br />

Organisational articles could provide information on newly<br />

published organisational guidelines or explain how a particular<br />

local service has been organised to benefit people with diabetes.<br />

— Diabetes & Primary Care Australia —

Editorial<br />

Diabetes and pregnancy<br />

It is well known that diabetes is a systemic<br />

condition and, if not managed efficiently,<br />

can have a life-changing impact on the eyes,<br />

feet and kidneys. In this <strong>issue</strong>, we consider<br />

the impact of uncontrolled hyperglycaemia on<br />

other body systems and functions – from skin<br />

to bone, and from pregnancy to older age. On<br />

page 75, Roy Rasalam and Lesley Weaving<br />

discuss the practical aspects of maintaining<br />

healthy skin in people with diabetes, and<br />

Neil Gittoes and Vidhya Jahagirdar provide a<br />

clinical review of the potential complications<br />

to bone health as a result of diabetes (page 61).<br />

There is a special section on diabetes and<br />

pregnancy covering preconception care in<br />

primary care and the resources available<br />

for women with diabetes and health care<br />

professionals (starting from page 47). Finally,<br />

there is a paper by Anna Chapman and<br />

Claudia Meyer on the increased risk of falls<br />

in older people with diabetes and what can be<br />

done to lower the risk (page 69). This topic is<br />

especially pertinent with the growing ageing<br />

population seen in Australia and globally.<br />

Diabetes and pregnancy<br />

One relatively new area of research in<br />

diabetes and pregnancy that has caught my<br />

eye is epigenetics – the effect of environment<br />

on genetics. Questions are being raised<br />

as to whether the maternal environment<br />

(e.g. maternal obesity, poor nutrition and<br />

hyperglycaemia) may “program” type 2<br />

diabetes in offspring. There is some evidence<br />

that suggests that shared genetic and<br />

environmental risk, as well as developmental<br />

programming, may lead to children born to<br />

women with diabetes during pregnancy at<br />

greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes in<br />

later life (Berends and Ozanne, 2012). If the<br />

female offspring then have their own children,<br />

it is thought that an intergenerational<br />

cycle of diabetes risk could be established<br />

(Dabelea and Crume, 2011). The intricacies<br />

of this are important to understand, as many<br />

women with pre-existing type 2 diabetes<br />

are often overweight or obese. They often<br />

continue to gain weight with each additional<br />

pregnancy and are sometimes reluctant to<br />

engage with health services (Bandyopadhyay<br />

et al, 2011). Women of South East Asian<br />

origin are at particularly high risk of diabetes<br />

during pregnancy, so by developing effective<br />

strategies to specifically address these factors,<br />

the risk of future diabetes to offspring may be<br />

reduced (Greenhalgh et al, 2015).<br />

What other considerations need to be<br />

made to avoid the increased risk of adverse<br />

pregnancy outcomes as a result of diabetes?<br />

Pre-gestational diabetes (type 1 and<br />

type 2 diabetes) is present in approximately<br />

1% of pregnant women in Australia and the<br />

prevalence is increasing not only here, but<br />

around the world. Women with pre-existing<br />

diabetes are at high risk of complications<br />

during pregnancy, with up to four times<br />

the rate of congenital malformations, and<br />

up to a five-fold increased risk of stillbirth<br />

and perinatal mortality compared to women<br />

without diabetes. By safely optimising blood<br />

glucose management, women can significantly<br />

reduce their risk of complications, and<br />

preconception care has been shown to reduce<br />

these risks (Inkster et al, 2006).<br />

Women of child-bearing age with diabetes<br />

need to be informed of the availability and<br />

importance of preconception care, which<br />

can be provided by both primary and<br />

specialised diabetes services; many women<br />

with type 1 diabetes access diabetes specialist<br />

services, while the majority of women with<br />

type 2 diabetes are managed in primary care.<br />

Included in preconception care is appropriate<br />

contraception advice. Here, primary care<br />

providers can make a real difference in<br />

promoting and providing appropriate<br />

contraception to women with diabetes to<br />

prevent unplanned pregnancies.<br />

In this pregnancy special, there are three<br />

pieces related to pregnancy and diabetes. There<br />

is a CPD module outlining the requirements<br />

of preconception care for women with<br />

Rajna Ogrin<br />

Editor of Diabetes & Primary Care<br />

Australia, and Senior Research<br />

Fellow, RDNS Institute,<br />

St Kilda, Vic.<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 45

Editorial<br />

“By considering the<br />

health and wellbeing of<br />

women with diabetes<br />

prior to pregnancy,<br />

we anticipate<br />

that meaningful<br />

improvements in<br />

pregnancy outcomes<br />

are possible.”<br />

diabetes, including practical information for<br />

health care providers, as well as case studies to<br />

highlight the application of this information<br />

in clinical practice (page 54). There is also<br />

a wealth of resources for the clinician and<br />

woman with diabetes to optimise healthy<br />

pregnancy outcomes. Melinda Morrison from<br />

the National Diabetes Services Scheme and<br />

colleagues outline the resources available,<br />

such as apps, booklets and online resources<br />

(page 50). We also have the first “From<br />

the other side of the desk” feature – a<br />

new series to inform clinical care from the<br />

perspectives of people with diabetes. In the<br />

first of the series, Karen Barrett discusses her<br />

journey with diabetes and how it affected her<br />

pregnancies (page 47).<br />

By considering the health and wellbeing<br />

of women with diabetes prior to pregnancy,<br />

and utilising the resources that have been<br />

developed specifically to support this group<br />

before, during and after pregnancy, we<br />

anticipate that meaningful improvements in<br />

pregnancy outcomes are possible. n<br />

2017 NATIONAL CONFERENCE<br />

Saturday 6th May 2017 – Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, Victoria, Australia<br />

The conference has been specifically designed for all primary care health<br />

professionals working in diabetes care to:<br />

Advance their education and learning in the field of diabetes health care<br />

Promote best practice standards and clinically effective care in the management of diabetes<br />

Facilitate collaboration between health professionals to improve the quality of diabetes<br />

primary care across Australia<br />

6TH MAY 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM<br />

The 2017 PCDSA national conference program will combine cutting edge scientific content with<br />

practical clinical sessions, basing the education on much more than just knowing the guidelines.<br />

The distinguished panel of speakers will share their specialised experience in an environment<br />

conducive to optimal learning. The Speaking faculty include, amongst others:<br />

Associate Professor<br />

Neale Cohen<br />

Director Clinical Diabetes<br />

Baker Heart and<br />

Diabetes Institute<br />

“Diabetes management<br />

and research in primary<br />

care – key components<br />

to improving outcomes”<br />

Doctor Christel<br />

Hendrieckx<br />

Senior Research Fellow<br />

The Australian Centre<br />

for Behavioural Research<br />

in Diabetes<br />

“The emotional health of<br />

people living with diabetes”<br />

For further information including the full 2017 program<br />

and to register for the conference please visit:<br />

www.eventful.com.au/pcdsa2017<br />

If you have any questions regarding the conference,<br />

please contact the Conference Secretariat;<br />

Toll free telephone: 1800 898 499<br />

Email: pcdsa@eventful.com.au<br />

Ms Renza Scibilia<br />

Manager - Type 1 Diabetes<br />

and Consumer Voice<br />

Diabetes Australia<br />

“Engaging people with<br />

diabetes, the diabetes<br />

online community and<br />

apps for diabetes”<br />

Doctor Gautam<br />

Vaddadi<br />

Consultant Cardiologist<br />

Alfred Health, Northern Health,<br />

University of Melbourne<br />

“The emerging importance<br />

of cardiac failure diagnosis<br />

and management in people<br />

with type 2 diabetes”<br />

pcdsa.com.au<br />

Bandyopadhyay M, Small R, Davey MA et al (2011) Lived<br />

experience of gestational diabetes mellitus among immigrant<br />

South Asian women in Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol<br />

51: 360–4<br />

Berends LM, Ozanne SE (2012) Early determinants of type 2<br />

diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 26: 569–80<br />

Dabelea D, Crume T (2011) Maternal environment and the<br />

transgenerational cycle of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes 60:<br />

1849–55<br />

Greenhalgh T, Clinch M, Afsar N et al (2015) Socio-cultural<br />

influences on the behaviour of South Asian women with<br />

diabetes in pregnancy: qualitative study using a multi-level<br />

theoretical approach. BMC Med 13: 120<br />

Inkster ME, Fahey TP, Donnan PT et al (2006) Poor glycated<br />

haemoglobin control and adverse pregnancy outcomes in<br />

type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Systematic review of<br />

observational studies BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6: 30<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

From the other side of the desk<br />

From the other side of the desk:<br />

Patient perspective<br />

Through diagnosis to pregnancy:<br />

My journey with diabetes<br />

Karen Barrett<br />

I<br />

was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes on Valentine’s<br />

Day, 1983, a day meant for chocolates, roses<br />

and sweets. What an irony it turned out to be.<br />

Dressed in my school uniform and ready for school,<br />

my Mum, being a nurse, had known for some time<br />

that something wasn’t right. I had lost a substantial<br />

amount of weight and the bathroom seemed to<br />

be my best friend, as did my unquenchable thirst.<br />

“Oh what a bombshell!” my Mum’s colleague said<br />

that day after hearing my diagnosis. I never really<br />

comprehended the significance of the diagnosis at<br />

the time. I had felt fine.<br />

In the early days after my diagnosis, to see my<br />

diabetes specialist meant a day off school and a trip<br />

to Canberra – that was the good part. The not-sogood<br />

part became the endless questions from the<br />

doctor – what was I putting in my mouth and at<br />

exactly what time of the day – measurements on the<br />

scales, numbers in books, pathology results and eye<br />

tests. On and on it went. Would I pass or fail? Had<br />

I been good or bad? I hated it.<br />

There was never a time that I let my diabetes<br />

stand in the way. I was quite sporty growing up<br />

in a small country town, later trying triathlons<br />

and endurance sports. But in my school life, I was<br />

sometimes left out, missing the first school camp<br />

because everyone was so very nervous to have a<br />

person with diabetes at camp and friends’ parents<br />

being reluctant to have me over, afraid of what or<br />

what not to feed me.<br />

As an adolescent, I was studious and quite fit and<br />

healthy, with an obsessive personality. That was<br />

until my late teens, when I seemed to burn out with<br />

school, with life and with diabetes. Life became<br />

tricky. I found solace in food and subsequently paid<br />

the price, gaining weight.<br />

My family, of course, was concerned, but the<br />

constant questions about how many blood sugar<br />

tests I was doing and whether I was looking after<br />

myself was a continuous reminder of my diabetes,<br />

something I wanted to forget. I ate in secret and lied<br />

to keep them satisfied while continuing to silently<br />

struggle. I was tired of all the rules, tired of all the<br />

questions and tired of being different and feeling<br />

restricted. As I entered adulthood, I thought I kept<br />

my struggles well hidden from others for many<br />

years. I went on to study nursing at university and<br />

the big wide world gave me even more freedom<br />

to hide from the reality of diabetes. Somehow,<br />

I stayed on the tightrope of avoiding routine<br />

doctor’s appointments while also avoiding more<br />

serious hospital admissions. A visit to the doctor<br />

would mean tests, which I knew I would fail, and<br />

questions that I would be ashamed to answer – I<br />

wasn’t up for the interrogations and judgements.<br />

But, I didn’t feel like I was failing! I was eating what<br />

I wanted, when I wanted, and being like the rest of<br />

my friends and peers.<br />

Time to get real<br />

Then I found out I was pregnant…unplanned.<br />

For me, I realised it was not fair to have a child,<br />

with the high risk of complications to me and my<br />

baby as a result of me not looking after myself.<br />

A decision, that I feel to this day, even though I<br />

agreed, had already been made for me. Time to get<br />

real. If I was to ever create a family of my own, it<br />

meant facing the <strong>issue</strong>s I had so long avoided – the<br />

medical world testing me on passing or failing at<br />

diabetes.<br />

Unable, and not allowing myself, to be anything<br />

other than perfectly controlled, I became a<br />

Citation: Barrett K (2017) Through<br />

diagnosis to pregnancy: My journey<br />

with diabetes. Diabetes & Primary<br />

Care Australia 1: 47–8<br />

About this series<br />

The aim of the “From the other<br />

side of the desk” series is to<br />

provide a patient perspective on<br />

a topic within diabetes, to reflect<br />

on the doctor–patient relationship<br />

and to inform clinical care.<br />

Author<br />

Karen Barrett, Registered Nurse<br />

and Coordinator, Central Coast,<br />

NSW.<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 47

From the other side of the desk<br />

“As a person with<br />

diabetes, my advice<br />

to the medical world<br />

would be to consider<br />

the person in front<br />

of you without their<br />

diabetes diagnosis.”<br />

champion of the tests. It was an intense time but<br />

my motivation to have healthy babies drove me<br />

to that perfection, and I went on to have three<br />

babies in 3 years. I told the medical team what they<br />

wanted to hear, but this time I wasn’t lying.<br />

It became my obsession to get the numbers<br />

right. Averaging about 12–14 blood sugars daily<br />

and the never-ending specialist appointments were<br />

vital to achieving the desired outcome. I was lucky<br />

that the care I received from my diabetes team<br />

during my pregnancies was excellent and well<br />

planned. I feel that it is vital to have a trusting<br />

relationship with an endocrinologist before, during<br />

and after pregnancies, and I was very fortunate<br />

to have that. But pregnancy with diabetes is not<br />

without its difficulties; the severe hypos during the<br />

first trimesters became frequent and increasingly<br />

exhausting, and with every pregnancy, I had<br />

another toddler to care for. My first-born was<br />

diagnosed with cerebral palsy (totally unrelated<br />

to my diabetes), and as if that was not sufficiently<br />

challenging, I became a single Mum when my<br />

youngest was 11 months old. Juggling three<br />

toddlers, a part-time job to survive financially and<br />

my diabetes became routine. The all-or-nothing<br />

personality has some advantages and in those<br />

3 years, I was switched to “all”, determined to be<br />

a good Mum.<br />

However, as the years went by, I let those<br />

numbers slip again. My three gorgeous children,<br />

my world, were growing up fast, and at aged 6, 7<br />

and 8 years, they kept me busy. I kept the medical<br />

team at length – I knew I wasn’t going to “pass the<br />

test”. My 7-year-old daughter, Presley, had spirit<br />

(sometimes too much!) and when she came down<br />

with a viral illness, as a mum with diabetes would,<br />

I checked her blood sugar. My Mum had suggested<br />

the “D” word as Presley kept sleeping through the<br />

day, which was very much unlike her. I still recall<br />

that moment, and I think I too knew something<br />

wasn’t right. Weeks later, Presley mentioned to me<br />

that she was waking through the night to go to the<br />

bathroom. I knew. I waited.<br />

My beautiful girl was dressed in her swimmers<br />

ready to go swimming. I did her blood sugar and<br />

there I was – the mother of a child with diabetes.<br />

Now it was me answering the questions not as a<br />

person with diabetes, but as a Mum. It was more<br />

than my own tests – I had to pass all of Presley’s<br />

tests as well.<br />

I felt my skills as a parent were put under the<br />

microscope. I believed it was all my fault if her<br />

numbers weren’t right. What was she eating when<br />

I wasn’t there? Was she exerting too much energy<br />

during lunchtime at school? Could she recognise<br />

a hypo? I felt like I had to live in her head, and<br />

I became the “helicopter” Mum. Presley too<br />

hated the medical world, clamming up at all the<br />

questions and hating the scales and numbers. At<br />

home, she dealt with the never-ending motherly<br />

concerns and requests to check her blood sugar,<br />

blaming every ailment or headache on diabetes,<br />

whether or not it was.<br />

Where I am now<br />

Despite some complications of my own, at 44 years<br />

of age, I now take care of myself and feel as well as<br />

I can feel, given my past “bad behaviour”. I have<br />

a good relationship with my team and appreciate<br />

the rapport I have with them, which has taken<br />

many years to establish and develop. I now take<br />

charge of my appointments and we talk about the<br />

concerns I have. The first questions asked are not<br />

“shall we look at the numbers?” or “how many<br />

highs/lows are you having?”; rather, “how are you,<br />

and what’s going on in your world?”<br />

I have had a lovely relationship with my<br />

psychologist who somehow allows me to be proud<br />

of who I am and what I have achieved. I am now<br />

free of the judgement calls that I thought were<br />

placed on me as a person with diabetes and then<br />

as the mother of a child with diabetes. Mistakes<br />

are human. Rough patches enable us all to make<br />

better choices, and experience allows us to call the<br />

shots. It’s OK not to be perfect. I truly hope that<br />

if anything, I can pass this on to my children and<br />

that they reach this point a whole lot sooner than<br />

I did.<br />

As a person with diabetes, my advice to the<br />

medical world would be to consider the person<br />

in front of you without their diabetes diagnosis.<br />

Diabetes management is far more than looking<br />

at the numbers. Consider their state of mind<br />

and the unsaid pressures they may have put on<br />

themselves. The bravest thing one can do is to ask<br />

for help and say that we’re not OK, and creating<br />

an environment where people with diabetes feel<br />

comfortable and safe to do so is vital. n<br />

48 Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

2017 NATIONAL CONFERENCE<br />

Saturday 6th May 2017 – Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, Victoria, Australia<br />

The conference has been specifically designed for all primary care health<br />

professionals working in diabetes care to:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Advance their education and learning in the field of diabetes health care<br />

Promote best practice standards and clinically effective care in the management of diabetes<br />

Facilitate collaboration between health professionals to improve the quality of diabetes<br />

primary care across Australia<br />

6TH MAY 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM<br />

The 2017 PCDSA national conference program will combine cutting edge scientific content with<br />

practical clinical sessions, basing the education on much more than just knowing the guidelines.<br />

The distinguished panel of speakers will share their specialised experience in an environment<br />

conducive to optimal learning. The Speaking faculty include, amongst others:<br />

Associate Professor<br />

Neale Cohen<br />

Director Clinical Diabetes<br />

Baker Heart and<br />

Diabetes Institute<br />

“Diabetes management<br />

and research in primary<br />

care – key components<br />

to improving outcomes”<br />

Doctor Christel<br />

Hendrieckx<br />

Senior Research Fellow<br />

The Australian Centre<br />

for Behavioural Research<br />

in Diabetes<br />

“The emotional health of<br />

people living with diabetes”<br />

Ms Renza Scibilia<br />

Manager - Type 1 Diabetes<br />

and Consumer Voice<br />

Diabetes Australia<br />

“Engaging people with<br />

diabetes, the diabetes<br />

online community and<br />

apps for diabetes”<br />

Doctor Gautam<br />

Vaddadi<br />

Consultant Cardiologist<br />

Alfred Health, Northern Health,<br />

University of Melbourne<br />

“The emerging importance<br />

of cardiac failure diagnosis<br />

and management in people<br />

with type 2 diabetes”<br />

For further information including the full 2017 program<br />

and to register for the conference please visit:<br />

www.eventful.com.au/pcdsa2017<br />

If you have any questions regarding the conference,<br />

please contact the Conference Secretariat;<br />

Toll free telephone: 1800 898 499<br />

Email: pcdsa@eventful.com.au<br />

pcdsa.com.au

Article<br />

Resources to support preconception care<br />

for women with diabetes<br />

Citation: Morrison M, Audehm R,<br />

Barry A et al (2017) Resources to<br />

support preconception care for<br />

women with diabetes. Diabetes &<br />

Primary Care Australia 2: 50–3<br />

Article points<br />

1. Women with diabetes are<br />

at increased risk of adverse<br />

pregnancy outcomes. Early<br />

intervention and planning<br />

can reduce the risks.<br />

2. Primary health care<br />

professionals have a key role<br />

in providing appropriate<br />

contraception to women with<br />

diabetes to prevent unplanned<br />

pregnancies, as well as<br />

encouraging optimal pregnancy<br />

planning and preparation.<br />

3. To address the gap in<br />

information for women with<br />

diabetes who are seeking<br />

or already accessing prepregnancy<br />

advice and<br />

care, Diabetes Australia<br />

has developed a suite of<br />

resources with funding<br />

through the National<br />

Diabetes Services Scheme.<br />

Key words<br />

– Diabetes in pregnancy<br />

– Education<br />

– Preconception care<br />

– Pregnancy<br />

– Resources<br />

– Type 1 diabetes<br />

– Type 2 diabetes<br />

Authors<br />

See page 53 for details.<br />

Melinda Morrison, Ralph Audehm, Alison Barry, Christel Hendrieckx,<br />

Alison Nankervis, Cynthia Porter, Renza Scibilia, Glynis P Ross<br />

Preconception care has been shown to reduce the rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes<br />

in women with pre-existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes. With an increasing prevalence of<br />

diabetes among women of child-bearing age, health professionals working in primary<br />

care have an important role in encouraging women with diabetes to plan and prepare<br />

for pregnancy. New resources, described here, are available for health professionals and<br />

women with diabetes and provide up to date, evidence-based information on pregnancy<br />

and diabetes.<br />

Pre-existing diabetes (type 1 or<br />

type 2 diabetes) is estimated to affect<br />

approximately 1% of pregnant women<br />

in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and<br />

Welfare, 2016), and evidence suggests that the<br />

prevalence is increasing (Abouzeid et al, 2014).<br />

In particular, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in<br />

pregnant women is expected to increase as a result<br />

of older maternal age, high rates of obesity and an<br />

ethnically diverse population (Cheung et al, 2005;<br />

Temple and Murphy, 2010).<br />

Diabetes in pregnancy has many welldocumented<br />

risks to both mother and baby<br />

(Macintosh et al, 2006; Dunne et al, 2009;<br />

Kitzmiller et al, 2010); however, these risks can<br />

be mitigated by effective preconception and<br />

pregnancy care, and most women with diabetes<br />

will go on to have a healthy pregnancy and a<br />

healthy baby (Ray et al, 2001; Wahabi et al, 2010;<br />

Holmes et al, 2017).<br />

While most women with type 1 diabetes access<br />

specialist services, the majority of women with<br />

type 2 diabetes are managed in primary care.<br />

Health professionals in primary care are often the<br />

first point of contact for women seeking pregnancy<br />

information, and have a key role in promoting and<br />

providing appropriate contraception to women<br />

with pre-existing diabetes to prevent unplanned<br />

pregnancies, and in specialist referral. They are<br />

also critically important in encouraging diabetesspecific<br />

preconception care in all women with<br />

pre-existing diabetes to optimise maternal and<br />

fetal outcomes (Temple and Murphy, 2010). In<br />

the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS)*<br />

Contraception, Pregnancy & Women’s Health<br />

Survey (2015) women with type 1 or type 2<br />

diabetes (n=967) indicated that diabetes specialists<br />

(endocrinologists and diabetes educators) and<br />

general practitioners were the health professionals<br />

with whom pregnancy and diabetes was most<br />

frequently discussed. Interestingly, the majority<br />

of women reported that they, rather than health<br />

professionals, initiated the conversation about<br />

pregnancy and diabetes.<br />

Preconception care in the primary<br />

health setting<br />

Despite the documented benefits of preconception<br />

care for women with pre-existing diabetes (Ray<br />

et al, 2001; Wahabi et al, 2010), many women<br />

with diabetes do not plan their pregnancies. Zhu<br />

et al (2012) reported that 45% of pregnancies in<br />

women with diabetes attending a tertiary obstetric<br />

hospital in Western Australia during 2009–2010<br />

*The National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) is an<br />

initiative of the Australian Government administered<br />

with the assistance of Diabetes Australia.<br />

50 Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

Resources to support preconception care for women with diabetes<br />

were unplanned. While in an earlier Australian<br />

multicentre study of pregnancies complicated<br />

by diabetes, pre-pregnancy counselling was<br />

documented in only 20% of women – 28% of<br />

those with type 1 diabetes and 12% of those with<br />

type 2 diabetes (McElduff et al, 2005).<br />

Planning for pregnancy<br />

The primary health care setting is where many<br />

women with diabetes seek advice on reproductive<br />

<strong>issue</strong>s and access contraception. However, in the<br />

NDSS Contraception, Pregnancy & Women’s<br />

Health Survey (2015) only 49% of Australian<br />

women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes could<br />

recall being advised by a health professional to<br />

use some form of contraception to prevent an<br />

unplanned pregnancy, and 55% could recall being<br />

advised by a health professional that they should<br />

access diabetes-specific pre-pregnancy care before<br />

becoming pregnant or planning a pregnancy.<br />

These results differed by type of diabetes, with<br />

those with type 2 diabetes being less likely to recall<br />

receiving advice. These findings are consistent<br />

with those reported in the TRIAD (Translating<br />

Research into Action for Diabetes) preconception<br />

study of US women aged 18–45 years enrolled<br />

in managed care (Kim et al, 2005). Of these<br />

women, 52% recalled discussions with a health<br />

professional regarding glucose control before<br />

conception, and 37% could recall receiving family<br />

planning advice.<br />

Due to the impact of an unplanned pregnancy<br />

on both the developing fetus and mother, adequate<br />

contraception should be maintained until<br />

glycaemia and all aspects of care are optimised.<br />

The longer-acting reversible contraceptives are an<br />

excellent choice (e.g. intrauterine contraceptive<br />

devices or implant) and are safe for women with<br />

diabetes to use. When reviewing contraception in<br />

women with diabetes, timing of pregnancy should<br />

be discussed. Preconception planning for women<br />

with diabetes should occur well before conception.<br />

If available, involvement of a specialist diabetes in<br />

pregnancy service is recommended.<br />

New NDSS resources to support<br />

preconception care<br />

To address the gap in information for<br />

women with diabetes who are seeking or<br />

already accessing pre-pregnancy advice<br />

and care, Diabetes Australia has developed<br />

a suite of resources with funding through<br />

the NDSS. These resources were developed<br />

following extensive consumer and stakeholder<br />

consultation, and provide up-to-date, evidencebased<br />

pregnancy information for women living<br />

with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The NDSS<br />

resources available include the following:<br />

l www.pregnancyanddiabetes.com.au: A<br />

website dedicated to pregnancy and diabetes<br />

information.<br />

l Pregnancy planning checklist: A checklist<br />

to help women with diabetes prepare for a<br />

healthy pregnancy. The checklist can be<br />

completed as an online tool or downloaded<br />

as a printable checklist (Figure 1).<br />

l Having a Healthy Baby booklets: Booklets<br />

providing comprehensive information on<br />

planning and managing pregnancy. Separate<br />

booklets are available for women with<br />

type 1 or type 2 diabetes (Figure 2).<br />

l NDSS pregnancy and diabetes factsheet:<br />

Available for download in English, Arabic,<br />

Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, Turkish,<br />

Urdu, Greek, Italian and Spanish.<br />

l Plan for the best start e-newsletter: A<br />

quarterly e-newsletter for women with<br />

diabetes and health professionals. It<br />

provides information on planning and<br />

preparing for pregnancy, and there is access<br />

to the latest NDSS resources and research<br />

updates.<br />

l Health professional continuing professional<br />

development learning: E-learning modules<br />

for primary health care providers on the<br />

topic of preconception care for women<br />

with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The course<br />

includes three modules with two nonassessed<br />

case studies and can be accessed<br />

from the NDSS pregnancy and diabetes<br />

website. CPD points are available for<br />

eligible health professionals.<br />

These resources for patients and health<br />

care professionals can be accessed at<br />

www.pregnancyanddiabetes.com.au. Hard<br />

copies of the booklets can be ordered online or<br />

by phoning the NDSS Helpline (1300 136 588).<br />

Page points<br />

1. Due to the impact of an<br />

unplanned pregnancy on<br />

both the developing fetus and<br />

mother, adequate contraception<br />

should be maintained until<br />

glycaemia and all aspects of<br />

care are optimised.<br />

2. Preconception planning for<br />

women with diabetes should<br />

occur well before conception.<br />

3. Resources for patients and<br />

health care professionals<br />

can be accessed at www.<br />

pregnancyanddiabetes.com.au.<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 51

Resources to support preconception care for women with diabetes<br />

Pregnancy Planning Checklist<br />

Plan and prepare at least 3-6 months before you start<br />

trying for a baby<br />

What you need to do BEFORE you fall pregnant<br />

Use contraception until you are ready to start trying for<br />

a baby (ask your doctor if this is the most reliable<br />

contraception suitable for you)<br />

Talk to your doctor for general pregnancy planning advice<br />

Make an appointment with health professionals who<br />

specialise in pregnancy and diabetes<br />

Aim for an HbA1c of less than 53mmol/mol (7%) if you<br />

have type 1 diabetes or 42mmol/mol (6%) or less if<br />

you have type 2 diabetes<br />

Review your diabetes management with your diabetes<br />

health professionals<br />

Have all your medications checked to see if they are<br />

safe to take during pregnancy<br />

Start taking a high-dose (2.5mg-5mg) folic acid<br />

supplement each day<br />

Have a full diabetes complications screening and<br />

your blood pressure checked<br />

Aim for a healthy weight before you fall pregnant<br />

For women<br />

with type 1<br />

or type 2<br />

diabetes<br />

Use this checklist as a guide to discuss with your health professionals<br />

www.pregnancyanddiabetes.com.au<br />

This checklist is intended as a guide only. It should not replace individual medical advice and if you have any<br />

concerns about your health or further questions, you should contact your health professional.<br />

The National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) is an initiative of the Australian Government administered with the assistance of Diabetes Australia.<br />

Figure 1. Pregnancy planning checklist, to help women with diabetes<br />

prepare for a healthy pregnancy. Produced by the National Diabetes<br />

Service Scheme.<br />

Other resources<br />

The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy<br />

Society (ADIPS)-endorsed Pregnant<br />

with Diabetes app has been developed<br />

for pregnant women with diabetes, and<br />

women with diabetes who intend to<br />

become pregnant (Figure 3). It is written by<br />

Prof. Elisabeth R Mathiesen and Prof. Peter<br />

Damm and is based on the recommendations<br />

of the Centre for Pregnant Women with<br />

Diabetes at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen,<br />

Denmark. The Australian version has been<br />

adapted by an Australian working party<br />

to reflect the ADIPS guidelines. The app<br />

can be downloaded from app stores free<br />

of charge. The information covered in the<br />

app is suitable for women with gestational,<br />

type 1 and type 2 diabetes and covers<br />

topics such as: how to plan for pregnancy,<br />

Figure 2. Booklets for women with type 1 and type 2<br />

diabetes. Produced by the National Diabetes Services<br />

Scheme.<br />

goal blood glucose levels, gestational weight<br />

gain, diet and carbohydrate intake, physical<br />

activity and insulin dosing.<br />

52 Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

Resources to support preconception care for women with diabetes<br />

National Development Program Expert<br />

Reference Group (2013–16). We acknowledge<br />

D. Charron-Prochownik for permission<br />

to reproduce questions from the RHAB<br />

questionnaire and V. Holmes for permission to<br />

use reproductive health knowledge questions<br />

in the NDSS Contraception, Pregnancy &<br />

Women’s Health Survey.<br />

Abouzeid M, Versace VL, Janus ED et al (2014) A population-based<br />

observational study of diabetes during pregnancy in Victoria,<br />

Australia, 1999–2008. BMJ Open 4: e005394<br />

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) Australia’s<br />

mothers and babies 2014-in brief. Perinatal statistics. AIHW,<br />

Canberra, ACT. Available at: http://www.aihw.gov.au/<br />

publication-detail/?id=60129557656 (accessed 14.03.17)<br />

“Primary care health<br />

professionals are<br />

also ideally placed to<br />

increase the awareness<br />

of women with<br />

diabetes about the<br />

available resources<br />

which are being<br />

actively reviewed and<br />

developed to meet<br />

their needs.”<br />

Cheung N, McElduff A, Ross G (2005) Type 2 diabetes in<br />

pregnancy: a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Aust N Z J Obstet<br />

Gynaecol 45: 479–83<br />

Figure 3. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy<br />

Society (ADIPS)-endorsed Pregnant with Diabetes app.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Primary health care providers play an important<br />

role in promoting effective contraception use<br />

and encouraging women with pre-existing<br />

type 1 or type 2 diabetes to plan and prepare<br />

for pregnancy. They are also ideally placed to<br />

increase the awareness of women with diabetes<br />

about the available resources which are being<br />

actively reviewed and developed to meet their<br />

needs.<br />

n<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The authors are grateful to the women who took<br />

part in the NDSS Contraception, Pregnancy<br />

& Women’s Health Survey, to the Australasian<br />

Diabetes in Pregnancy Society for approving the<br />

use of the image of the Pregnant with Diabetes<br />

app and to Effie Houvardas and Kaye Farrell,<br />

for their contribution to Diabetes in Pregnancy<br />

Dunne FP, Avalos G, Durkan M et al (2009) ATLANTIC DIP:<br />

pregnancy outcome for women with pregestational diabetes<br />

along the Irish Atlantic seaboard. Diabetes Care 32: 1205–6<br />

Holmes VA, Hamill, LL, Alderdice FA et al (2017) Effect of<br />

implementation of a preconception counselling resource for<br />

women with diabetes: A population based study. Primary Care<br />

Diabetes 11: 37–45<br />

Kim C, Ferrara A, McEwan LN et al (2005) Preconception care in<br />

managed care: the translating research into action for diabetes<br />

study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192: 227–32<br />

Kitzmiller JL, Wallerstein R, Correa A, Kwan S (2010)<br />

Preconception care for women with diabetes and prevention of<br />

major congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol<br />

Teratol 88: 791–803<br />

Macintosh MC, Fleming KM, Bailey JA et al (2006) Perinatal<br />

mortality and congenital anomalies in babies of women with<br />

type 1 or type 2 diabetes in England, Wales, and Northern<br />

Ireland: population based study. BMJ 333: 177<br />

McElduff A, Ross GP, Lagstrom JA et al (2005) Pregestational<br />

diabetes and pregnancy: an Australian experience. Diabetes<br />

Care 28: 1260–1<br />

National Diabetes Services Scheme (2015) NDSS Diabetes<br />

in Pregnancy National Development Program, Registrant<br />

Consultation and Needs Assessment Report. NDSS, Canberra,<br />

ACT<br />

Ray JG, O’Brien TE, Chan WS (2001) Preconception care and the<br />

risk of congenital anomalies in the offspring of women with<br />

diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. QJM 94: 435–44<br />

Temple RC, Murphy H (2010) Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy - an<br />

increasing problem. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 24:<br />

591–603<br />

Wahabi HA, Alzeidan RA, Bawazeer GA et al (2010)<br />

Preconception care for diabetic women for improving maternal<br />

and fetal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.<br />

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10: 63<br />

Zhu H, Graham D, Teh RW, Hornbuckle J (2012) Utilisation of<br />

preconception care in women with pregestational diabetes in<br />

Western Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 52: 593–6<br />

Authors<br />

Melinda Morrison, NDSS<br />

Diabetes in Pregnancy Priority<br />

Area Leader*, Diabetes, NSW,<br />

Glebe, NSW; Ralph Audehm,<br />

General Practitioner, Carlton<br />

Family Medical and Department<br />

of General Practice, University<br />

of Melbourne, Vic; Alison Barry,<br />

Credentialled Diabetes Educator<br />

and Midwife, Mater Mothers’<br />

Hospital, South Brisbane, Qld;<br />

Christel Hendrieckx, Senior<br />

Research Fellow, The Australian<br />

Centre for Behavioural Research<br />

in Diabetes, Deakin University,<br />

Geelong, Vic; Alison Nankervis,<br />

Senior Physician to the Diabetes<br />

Service, The Royal Women’s<br />

Hospital and Clinical Head,<br />

Diabetes, Royal Melbourne<br />

Hospital, Parkville, Vic; Cynthia<br />

Porter, Advanced Accredited<br />

Practising Dietitian/Credentialled<br />

Diabetes Educator, Geraldton<br />

Diabetes Clinic, Geraldton, WA;<br />

Renza Scibilia, Manager Type 1<br />

Diabetes and Consumer Voice,<br />

Diabetes Australia, Melbourne,<br />

Vic; Glynis P Ross, Visiting<br />

Endocrinologist, Royal Prince<br />

Alfred Hospital, Camperdown,<br />

NSW, and Senior Endocrinologist,<br />

Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital,<br />

Bankstown, NSW.<br />

*Melinda Morrison is representing<br />

Diabetes Australia/National<br />

Diabetes Service Scheme.<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 53

CPD module<br />

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for<br />

women with pre-gestational diabetes in<br />

primary health care<br />

Glynis P Ross<br />

Citation: Ross GP (2017) Optimising<br />

pregnancy outcomes for women<br />

with pre-gestational diabetes in<br />

primary health care. Diabetes &<br />

Primary Care Australia 2: 54–9<br />

Learning objectives<br />

After reading this article, the<br />

participant should be able to:<br />

1. Identify the increased<br />

risks of adverse pregnancy<br />

outcomes to mother and<br />

baby that are associated with<br />

pre-gestational diabetes.<br />

2. Describe the ideal<br />

preconception care<br />

consultation and the key<br />

elements of care that a pregnant<br />

woman with pre-existing<br />

diabetes should receive.<br />

3. Implement a checklist for<br />

preconception care for<br />

women with diabetes.<br />

Key words<br />

– Preconception care<br />

– Pre-gestational diabetes<br />

– Pregnancy<br />

– Type 1 diabetes<br />

– Type 2 diabetes<br />

Author<br />

Glynis P Ross, Visiting<br />

Endocrinologist, Royal Prince<br />

Alfred Hospital, Camperdown<br />

NSW, and Senior Endocrinologist,<br />

Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital,<br />

Bankstown, NSW.<br />

Preconception care for women with pre-existing diabetes (type 1 or type 2) is critical to<br />

optimise pregnancy outcomes and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes, including miscarriage,<br />

congenital anomalies, hypertension, caesarean deliveries and perinatal mortality. Pregestational<br />

diabetes is present in approximately 1% of pregnant women in Australia, and the<br />

prevalence is increasing. Women with pre-gestational diabetes need to be informed on the<br />

availability and importance of preconception care, which can be provided by both primary<br />

care and specialised diabetes services. The key elements of preconception care for women<br />

with diabetes are outlined in this article with two case examples to illustrate.<br />

Women with pre-gestational type 1<br />

or type 2 diabetes are at high risk<br />

of complications during pregnancy<br />

and of adverse outcomes including miscarriage,<br />

congenital anomalies and perinatal mortality.<br />

Despite advances in diabetes management, rates<br />

of congenital anomalies are 2–4 times higher<br />

than that of the background population and<br />

there is a 3–5 fold increased risk of stillbirth<br />

and perinatal mortality for births to women<br />

with diabetes (Macintosh et al, 2006; Dunne et<br />

al, 2009; Kitzmiller et al, 2010). Data from the<br />

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2010)<br />

show that in 2005–2007, more than half of all<br />

Australian women with pre-gestational diabetes<br />

underwent caesarean delivery (59%; 71% type 1<br />

and 56% type 2 diabetes), compared to a third of<br />

women without diabetes. Following birth, 58%<br />

of infants born to women with diabetes were<br />

admitted to a special care nursery or neonatal<br />

intensive care unit, compared to 14% of babies<br />

born to mothers without diabetes.<br />

Glycaemic control in early pregnancy is strongly<br />

associated with the risk of adverse pregnancy<br />

outcomes (Nielsen et al, 2004; Guerin et al, 2007,<br />

Jensen et al, 2009). Research shows that for every<br />

10.93 mmol/mol (1%) increase in HbA 1c<br />

above<br />

53 mmol/mol (7%), there is a 5.5% increase in<br />

risk of adverse outcomes (Nielsen et al, 2004). The<br />

American Diabetes Association (2017) states that<br />

the lowest rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes<br />

are seen in association with an early gestation<br />

HbA 1c<br />

of 42–48 mmol/mol (6.0–6.5%).<br />

Preconception care for women with existing<br />

diabetes provides an opportunity to optimise<br />

glycaemic control, as well as other aspects of<br />

maternal health such as folic acid supplementation,<br />

diabetes complications screening and<br />

discontinuation of teratogenic medications prior<br />

to conception (McElduff et al, 2005; Mahmud<br />

and Mazza, 2010; Egan et al, 2015). Attendance<br />

at diabetes-specific preconception care has<br />

been associated with a reduction in congenital<br />

anomalies (relative risk [RR], 0.25), perinatal<br />

mortality (RR, 0.35) and reduced first trimester<br />

HbA 1c<br />

by an average of 26 mmol/mol (2.4%;<br />

Wahabi et al, 2010).<br />

Advice<br />

Preconception planning and assessment is<br />

recommended for all women considering<br />

pregnancy, but it is particularly important for<br />

women with diabetes or other medical disorders.<br />

Primary health care providers are well placed to<br />

complete most of the preconception screening<br />

and risk assessment, and can facilitate many of<br />

54 Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-gestational diabetes in primary health care<br />

the interventions and appropriate referrals that<br />

may be required. A checklist, such as below,<br />

may be useful when undertaking pre-pregnancy<br />

counselling.<br />

ADVICE AND CONSIDERATIONS<br />

FOR ALL WOMEN CONSIDERING<br />

PREGNANCY<br />

o Appropriate contraception until<br />

optimal situation for pregnancy.<br />

o Review ALL current medications<br />

and ensure they are safe and<br />

appropriate for pregnancy.<br />

o Check blood pressure.<br />

o (For women not known to<br />

have diabetes, assess risk,<br />

and test appropriately for<br />

abnormal glucose tolerance.)<br />

o Promote a healthy lifestyle<br />

with regard to diet, exercise<br />

and optimal weight – this is<br />

also advisable for partners!<br />

o Encourage smoking cessation.<br />

o Advise to cease alcohol intake.<br />

o Advise to stop any<br />

recreational drug use.<br />

o Reduce caffeine intake.<br />

o Dental check.<br />

o Complete breast check<br />

and pap smear.<br />

o Assess immunity to rubella<br />

and varicella zoster, and, if<br />

necessary, organise vaccinations<br />

with appropriate waiting<br />

periods before conception.<br />

o Consider vaccinations for<br />

influenza and whooping cough.<br />

o Commence folic acid 3 months<br />

prior to pregnancy at 0.5 mg daily<br />

(see below for dose adjustments<br />

for women with known diabetes).<br />

o Commence an iodine-containing<br />

supplement (unless active<br />

thyrotoxicosis is present).<br />

o Consider checking thyroid<br />

function, iron, B12 (especially if<br />

vegetarian or taking metformin)<br />

and vitamin D status (if at risk).<br />

ADDITIONAL ADVICE AND<br />

CONSIDERATIONS FOR WOMEN<br />

WITH PRE-GESTATIONAL DIABETES<br />

CONSIDERING PREGNANCY<br />

o Refer to a diabetes specialist<br />

or team if not already under<br />

their care for assessment.<br />

o Optimise glycaemic control<br />

o In type 1 diabetes, pre-pregnancy<br />

HbA 1c<br />

should ideally be<br />

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-gestational diabetes in primary health care<br />

Page points<br />

1. Preconception care should be<br />

individualised.<br />

2. Women should be advised<br />

to continue to use effective<br />

contraception until the best<br />

possible conditions for a<br />

safe pregnancy and birth are<br />

achieved.<br />

3. Regular monitoring and<br />

recording of blood glucose<br />

levels during the preconception<br />

stage and pregnancy can be<br />

helpful in optimising pregnancy<br />

outcomes.<br />

Case studies<br />

Outlined on the following two pages are two case<br />

studies illustrating some of the considerations to<br />

address during the preconception period. Given<br />

the range of situations that may be encountered,<br />

all care needs to be individualised. Ideally, most<br />

women with diabetes should be assessed before<br />

conception by a diabetes specialist or team with<br />

expertise in diabetes and pregnancy. This is<br />

particularly important when there are diabetes<br />

complications or additional medical disorders.<br />

For women in rural and remote areas, review<br />

in a regional centre or via telehealth with a<br />

specialist centre may be an appropriate option.<br />

This is especially important for women with more<br />

complex situations such as type 1 diabetes, type 2<br />

diabetes requiring multiple medications, diabetes<br />

vascular complications and/or other vascular risk<br />

factors.<br />

Case 1<br />

Maria is a 41-year old woman and has come<br />

to see you for a pap smear. You last saw her<br />

4 months ago when she wanted a script for<br />

the oral contraceptive pill (OCP). On routine<br />

questioning when you are completing the<br />

pathology request for cervical cytology she says<br />

that she is considering having a break from the<br />

pill as she and her husband are thinking about<br />

having another baby.<br />

History<br />

Maria has two children aged 9 and 12 years.<br />

The first pregnancy was uncomplicated and she<br />

had spontaneous vaginal delivery at term. Her<br />

daughter weighed 3450 g and was breastfed<br />

for 12 months. Before her second pregnancy,<br />

Maria had gained 8 kg in weight and her BMI<br />

was 28 kg/m 2 . At 28 weeks during her second<br />

pregnancy, Maria was diagnosed with gestational<br />

diabetes. She was able to manage this with diet<br />

modification alone and had spontaneous vaginal<br />

delivery at 39 +3 weeks of a 3720 g son. He was<br />

also breastfed for 12 months.<br />

Three years ago (age 38 years), Maria’s<br />

weight had risen and her BMI was 31 kg/m 2<br />

(class 1 obesity range). Her fasting glucose was<br />

7.2 mmol/L and her HbA 1c<br />

was 49 mmol/mol<br />

(6.6%) and a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes was<br />

made. Initially she was treated with metformin<br />

XR 2 g daily. Despite the metformin and Maria<br />

trying to follow dietary guidelines, 4 months<br />

ago her HbA 1c<br />

was 62 mmol/mol (7.8%) and so<br />

empagliflozin was added to her regimen. She<br />

continued to struggle to find time to exercise.<br />

Maria has a strong family history of<br />

type 2 diabetes (both parents, her older brother<br />

and all grandparents) and hypertension (father<br />

and paternal grandmother). Her father had a<br />

myocardial infarct at the age of 39 years with<br />

subsequent stenting. For 7 years, Maria has also<br />

been treated for hypertension with telmisartan,<br />

and dyslipidaemia for which she is taking<br />

atorvastatin and fenofibrate. She and her husband<br />

smoke, but Maria has said she is trying to stop<br />

so is only smoking in the evenings after dinner.<br />

Discussion<br />

Maria has several factors that increase her<br />

risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. She is of<br />

advanced maternal age, is obese, a smoker, and<br />

has type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia<br />

and a family history of early-onset ischaemic<br />

heart disease.<br />

Her glycaemic control is not satisfactory for<br />

pregnancy, and although metformin can be<br />

continued during pregnancy, empagliflozin<br />

will need to be stopped and insulin therapy<br />

commenced and titrated. She will need to increase<br />

her blood glucose monitoring and recording of<br />

results, preferably including dietary information.<br />

Review with a dietitian, diabetes educator and<br />

preferably an exercise physiologist is advisable.<br />

She should be seen by a diabetes physician with<br />

expertise in diabetes and pregnancy.<br />

She has multiple vascular risk factors and a<br />

high risk of developing a hypertensive disorder of<br />

pregnancy. She should be appropriately counselled<br />

regarding smoking cessation. The medication she<br />

is on for hypertension needs to be changed and<br />

the lipid management will need to be stopped<br />

for pregnancy. As she has hypertension it would<br />

be preferable that she is also seen by a renal or<br />

obstetric medicine physician, especially if she<br />

fails to achieve blood pressure targets or if she<br />

has overt proteinuria. Given the multiple vascular<br />

risk factors, she should have a pre-pregnancy<br />

cardiac assessment.<br />

56 Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-gestational diabetes in primary health care<br />

Advice<br />

You advise Maria that she should stay on the<br />

OCP for the time being and that preconception<br />

planning is needed in view of her multiple medical<br />

conditions and medications. If she still wishes to<br />

become pregnant, she should commence highdose<br />

folic acid and have routine pre-pregnancy<br />

checks. If she conceives, her contraception choice<br />

should be reviewed following the pregnancy as it<br />

is not advisable for her to continue on the OCP<br />

given her age and vascular risk status.<br />

Case 2<br />

Jennifer has come to see you for a referral letter to<br />

her gynaecologist. She wants to have her intrauterine<br />

contraceptive device (IUCD) removed as she is<br />

keen to start a family. Jennifer is a 30-year-old<br />

woman who has had type 1 diabetes for 21 years.<br />

For the last 3 years, she has been using insulin<br />

pump therapy. Jennifer’s most recent HbA 1c<br />

of<br />

70 mmol/mol (8.6%) was higher than usual after a<br />

recent overseas holiday with her husband.<br />

History<br />

In her teens, Jennifer struggled with her diabetes<br />

control but in the past 5 years has been managing<br />

quite well. Her last episode of diabetic ketoacidosis<br />

was 18 months ago when there was a problem with<br />

insulin delivery through her pump. She has not<br />

had severe hypoglycaemia (requiring the assistance<br />

of another person) for 5 years and is using a<br />

continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS)<br />

with predictive low-glucose suspend, as she knows<br />

that she does not reliably sense hypoglycaemia.<br />

Jennifer has diabetic retinopathy that has<br />

previously required laser photocoagulation.<br />

However, she has not had her eyes checked for<br />

about 2 years as she missed an appointment and<br />

did not find time to reschedule. She has overt<br />

proteinuria (0.5 g per day) and is on ramipril for<br />

nephroprotection. Her eGFR is 62 mL/min/1.73 m 2<br />

and she has previously been assessed for other<br />

causes of renal disease by a nephrologist. Her<br />

blood pressure and lipids are normal. She has<br />

a moderate degree of asymptomatic peripheral<br />

neuropathy with loss of distal sensation to light<br />

touch and vibration, as well as loss of ankle<br />

reflexes. She senses a monofilament and has had<br />

no diabetes-related foot complications.<br />

Discussion<br />

If conception is successful, this will be Jennifer’s<br />

first pregnancy. As she is on insulin pump therapy<br />

and uses a CGM device, she will already be under<br />

a specialist diabetes team. Her glycaemic control<br />

is sub-optimal and significantly increases her<br />

risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including<br />

miscarriage and congenital anomalies. Even<br />

though the recommended HbA 1c<br />

target for women<br />

with type 1 diabetes in the preconception stage is<br />

≤53 mmol/mol (7%), given her long duration<br />

of type 1 diabetes and poor hypoglycaemic<br />

awareness, it may not be safe to reduce her HbA 1c<br />

below 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) due to the increasing<br />

risk of severe hypoglycaemia at lower levels. She<br />

needs specific specialist assessment and advice<br />

regarding her HbA 1c<br />

as well as review of all<br />

aspects of her diabetes self-management (e.g. diet,<br />

exercise, BGL testing and recording, insulin pump<br />

settings review, pump management skills, driving<br />

considerations, and hypoglycaemia and diabetic<br />

ketoacidosis prevention and management).<br />

Jennifer also needs an urgent diabetes eye<br />

review. If there is active proliferative retinopathy or<br />

macular oedema she will need to delay pregnancy<br />

plans until the retinopathy has been treated and<br />

is stable. As she has overt proteinuria, she should<br />

be assessed pre-pregnancy by a renal or obstetric<br />

medicine physician who will be able to continue<br />

to manage her in pregnancy. Her risk of preeclampsia<br />

and poor fetal outcomes, including<br />

intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), will be<br />

increased. Although she is not known to have<br />

autonomic neuropathy, she should be assessed for<br />

this by her diabetes specialist.<br />

Advice<br />

You advise Jennifer to not have the IUCD<br />

removed yet and that preconception planning is<br />

needed in view of her complex diabetes situation<br />

– especially her overall glycaemic control,<br />

nephropathy and retinopathy. You also ask her<br />

whether she has discussed pregnancy with her<br />

endocrinologist and check the date of her next<br />

scheduled appointment. Following diabetes<br />

complications assessment and optimising<br />

glycaemic management, Jennifer should<br />

commence high-dose folic acid and have routine<br />

pre-pregnancy checks.<br />

”If a woman has<br />

been diagnosed with<br />

retinopathy, it is<br />

important to ensure<br />

it has been treated<br />

and is stable prior to<br />

pregnancy.”<br />

Diabetes & Primary Care Australia Vol 2 No 2 2017 57

Optimising pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-gestational diabetes in primary health care<br />

“Primary health<br />

care providers have<br />

critical roles to play<br />

in the assessment<br />

and management of<br />

contraception,<br />

pre-pregnancy<br />

assessment<br />

and care.”<br />

Conclusion<br />

Women of child-bearing age with pre-gestational<br />

type 1 or type 2 diabetes need to be counselled<br />

on the need for appropriate contraception at all<br />

times unless trying for pregnancy in the best<br />

possible circumstances to avoid adverse pregnancy<br />

outcomes. Most women with pre-gestational<br />

diabetes are able to have successful pregnancies.<br />

However, they are at much higher risk of having<br />

adverse pregnancy outcomes than women without<br />

diabetes (Macintosh et al, 2006; Dunne et al,<br />

2009). It has been shown that women who have<br />

had optimal pre-pregnancy care and best practice<br />