Et Alors? Magazine 20

Et Alors? Magazine is a project in motion, co-created by female artist duo and lovers JF. Pierets - Fleur Pierets and Julian P. Boom - who’s work questions the mainstream understandings and the construction of (gay) identity. An ongoing research platform where they publish their conversations with musicians, visual artists, writers and performers by whom they are inspired, hereby capturing the zeitgeist of a world in the midst of its striving for change and it’s cultural awareness when it comes to gay imagery and female representation in mainstream art history. www.etalorsmagazine.com

Et Alors? Magazine is a project in motion, co-created by female artist duo and lovers JF. Pierets - Fleur Pierets and Julian P. Boom - who’s work questions the mainstream understandings and the construction of (gay) identity. An ongoing research platform where they publish their conversations with musicians, visual artists, writers and performers by whom they are inspired, hereby capturing the zeitgeist of a world in the midst of its striving for change and it’s cultural awareness when it comes to gay imagery and female representation in mainstream art history.

www.etalorsmagazine.com

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

et alors?<br />

a flamboyant art magazine

editorial<br />

Comrades!<br />

It’s been a while since our last edition of <strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong> but here<br />

we are!<br />

Times have been hectic and challenging lately, and we needed a<br />

moment to reflect our lives and our work. After some deliberation<br />

we recently released a website with our own artwork. Have a look<br />

via www.jfpierets.com. We’ve been thinking and working on the<br />

material for quite some time, however it’s been only since the last<br />

couple of months that we felt the need to make it public.<br />

And let me share our latest art project with you, called 22. 22 will<br />

take off as from September <strong>20</strong>17, when we will get married in<br />

every country that has legalised same-sex marriage. Out of the 194<br />

countries in the world, only 22 recognise and provide gay marriage.<br />

When saying these numbers out loud, we found that most people<br />

are not aware of this fact, so we have created a positive artwork<br />

that celebrates the countries that do allow it, while highlighting an<br />

issue that still needs work.<br />

Taking all our new projects into account, we also felt it was time<br />

to mould <strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong> into a format that reflects who we<br />

are, and what it is exactly we need to put out there, even more.<br />

Integrating the magazine into our art practice is one of the first<br />

steps. As from now on we will publish our ‘artist talks’ the moment<br />

they occur. Every once in a while we will bundle them into a new<br />

issue of <strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong>. Hereby creating an accurate timecapsule<br />

of what we did, who we spoke to, what we’ve made and<br />

what inspired us over that period of time.<br />

I truly hope you stay with us in this new adventure.<br />

At this moment we’re getting ready for our trip to New York. To<br />

start our 22 pre-production, write the documentary script and to<br />

continue our hunt for patrons. To get everything ready and set up<br />

for our first wedding there in September. A camera crew will follow<br />

us over the 18 month course of the performance to later create a<br />

50-minute making-of documentary. To be released in the spring of<br />

<strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong>. In <strong>20</strong>19 we will exhibit the art/video installation of 22 for the<br />

first time. A book with all our adventures will follow later that year.<br />

Why do all that? Because at the current rate, we will reach global<br />

recognition of same-sex marriage in the year 2142. That’s 125 years<br />

from now! Let’s see if we can get it to go a bit faster.<br />

Enjoy our new issue of <strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong>.<br />

Made proudly and with tons of good vibes, as always.<br />

Keep safe, stay gorgeous!<br />

Fleur & Julian<br />

003

et alors? magazine<br />

july <strong>20</strong>17<br />

issue <strong>20</strong><br />

Text & Research<br />

Fleur Pierets<br />

Artwork & Layout<br />

Julian P. Boom<br />

Contributors<br />

Bernard Perlin<br />

Dietmar Busse<br />

Faryda Moumouh<br />

Gazelle Paulo<br />

JF. Pierets<br />

Johnny Rozsa<br />

Jorge Clar<br />

Michael Schreiber<br />

Ron Amato<br />

Van Wifvat<br />

A very special thanks to<br />

Ingrid Van Den Bossche<br />

Tracy Atkins<br />

table of contents<br />

Editorial<br />

Table of contents<br />

Nadia Naveau<br />

Faryda Moumouh<br />

22<br />

Jorge Clar<br />

Bernard Perlin<br />

Clark Kent<br />

003<br />

004<br />

006<br />

022<br />

034<br />

036<br />

048<br />

064<br />

www.etalorsmagazine.com<br />

www.jfpierets.com<br />

www.22theproject.com<br />

© All material in this magazine is copyrighted as indicated.<br />

004

<strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong> is a project<br />

in motion, co-created by female<br />

artist duo and lovers JF. Pierets<br />

- Fleur Pierets and Julian P.<br />

Boom - who’s work questions<br />

the mainstream understandings<br />

and the construction of (gay)<br />

identity. An ongoing research<br />

platform where they publish their<br />

conversations with musicians,<br />

visual artists, writers and<br />

performers by whom they are<br />

inspired, hereby capturing the<br />

zeitgeist of a world in the midst<br />

of its striving for change and<br />

it’s cultural awareness when it<br />

comes to gay imagery and female<br />

representation in mainstream art<br />

history.<br />

info@etalorsmagazine.com<br />

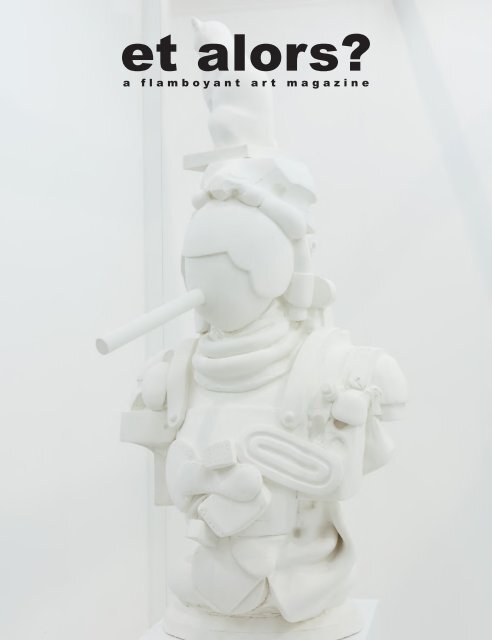

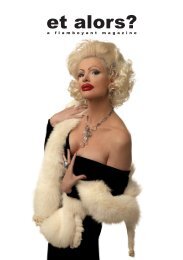

Cover<br />

Nadia Naveau<br />

Antwerp, Belgium<br />

Sculptor<br />

www.basealphagallery.be<br />

et alors?<br />

a flamboyant art magazine<br />

005

nadia<br />

naveau<br />

text jf. pierets<br />

007

I’m going to start with a quote by Ai Weiwei:<br />

“Being an artist is not a job, it’s an identity”.<br />

Definitely! From the moment I started at the academy<br />

I noticed that sculpting was very demanding on<br />

both a physical and a psychological level. This has<br />

never diminished. I very much like what I do, but<br />

a large percentage of my practice involves - let’s<br />

call it ‘suffering’ for lack of a better word. You can’t<br />

underestimate the hard work involved in a creative<br />

process. Maybe it has something to do with my<br />

perfectionism and the way I always seek to surprise<br />

myself. I am able to make large and complex series<br />

like Salon du Plaisir - but then I have to change<br />

everything and make it challenging again. I want<br />

to keep finding things that I don’t know yet. I want<br />

to keep on being amazed. Those steps can be very<br />

small, and they may not even be noticed by the<br />

public, but for me they are very important. That’s<br />

the thing I’m pursuing. That doesn’t mean it always<br />

works out. So when it doesn’t, I’ll feel unhappy and<br />

unsatisfied. But when it does you have the feeling<br />

that you can literally do anything. It’s a never ending<br />

circle which I’m quite familiar with by now, but when<br />

I was younger I definitely considered giving up art<br />

and starting a day job.<br />

Can you describe what you are looking for?<br />

That’s difficult to explain because in the first<br />

place it’s about a certain tension between shapes,<br />

between abstract or organically formed elements.<br />

I’m also looking for surprise. I’m always curious and<br />

never satisfied with things I already know. I keep<br />

searching for the new. Although ‘searching’ may<br />

be the wrong word because I have the feeling that<br />

I bump into things. They’re just there when I need<br />

them. When I’m in this creative flow, things come<br />

my way. Those things can be very banal. It can be a<br />

color, a shape, or even a chip of wood from a chair.<br />

Everything automatically makes sense and comes<br />

to terms with what I’m working on at the moment.<br />

I know it all sounds a bit abstract but it makes sense<br />

in my head.<br />

I guess you can compare it to a jigsaw puzzle where<br />

every piece automatically leads to the big picture.<br />

If you say you want to surprise yourself, does that<br />

mean that you never know the outcome?<br />

Not always, no. All the images in my mind translate<br />

into the clay as some sort of collage. Sometimes I<br />

don’t know where an image comes from, yet when<br />

the piece is finished and I start talking about it, spend<br />

time with it, it all matches up. It all becomes clear.<br />

I notice I keep on fostering connections between<br />

what I did before and how I can make it more<br />

abstract, or make a different version of it. Every<br />

piece is a step forward to the next one. Even little<br />

things like collages or pictures I make, are a prelude<br />

to the piece that comes next.<br />

My intuition is often faster than my interpretation<br />

or reason.<br />

What makes you go to your studio every time?<br />

Discipline and action. When I’m - for one reason or<br />

another - a bit rusty, I start making things through<br />

boredom. Things I know, things that don’t take<br />

any effort. I start sculpting Nick (Nadia’s husband,<br />

painter Nick Andrews), which gets me going most<br />

of the time. It’s all about doing things. I get a lot<br />

of inspiration from magazines, from traveling or<br />

design, but in the end you just have to start and see<br />

where it leads you. However, I’ve also learned that<br />

it’s not bad to take a break every now and then.<br />

Especially after an exhibition when it’s important to<br />

wind down. And even when feelings of guilt start to<br />

kick in, I always acknowledge the value of just doing<br />

nothing for a while. Sometimes you just have to let<br />

go.<br />

Some African languages don’t have a word for<br />

artist, but translate it as magician: someone who<br />

puts magical powers into an object? What do you<br />

put into your work?<br />

I have the feeling that I literally put everything<br />

into my work. And since I often cannot recall how<br />

I’ve made something, the fear of not being able to<br />

do it anymore lingers once in a while. Even when<br />

everything always works out fine, I cannot say that<br />

the process is obvious. It’s a huge contrast to when<br />

I’m feeling confident. The greatest moment is when<br />

you feel that everything connects, when you are<br />

in the middle of this creative process where all the<br />

pieces come together. Then I can even say that I’ve<br />

made the best thing I’ve ever seen! This doesn’t mean<br />

I’ll have that same feeling the next day, but it’s a good<br />

start. It’s an addictive feeling though. The adrenaline<br />

you feel when you’re on a confidence high is great. It’s<br />

very empowering. Enough to keep me going through<br />

the tougher times. Thankfully I’m able to put it more<br />

and more into perspective because absolutely no<br />

creativity comes from being in a negative loop.<br />

008

012<br />

‘I like people<br />

to experience<br />

what they think<br />

and feel for<br />

themselves. Art<br />

opens people’s<br />

minds.’

happy to have the possibility to exhibit and enjoy the<br />

fact that people are seeing what I’ve done. It’s also<br />

very nice that after all this time of solitude, you get<br />

to put your work out there. It can be very rewarding.<br />

‘As an artist<br />

you have to be<br />

determined. And<br />

be disciplined.<br />

Without lapsing<br />

into a regular<br />

pattern. Because<br />

then you stop<br />

evolving.’<br />

Do you see the world differently as an artist?<br />

Probably. But I have difficulty saying so because to<br />

me it sounds very pretentious. But there is indeed<br />

a big difference between how I view the world and<br />

how, for example, my parents are experiencing<br />

it. Maybe that’s what they call ‘a trained eye’?<br />

However, being a good artist is not only about how<br />

you see the world. It’s not even solely about talent.<br />

You also have to be determined. And be disciplined.<br />

Without lapsing into a regular pattern. Because then<br />

you stop evolving. An art collector once told me that<br />

he kept on buying my work because he loved to see<br />

how I was evolving. And how he always stops buying<br />

pieces from artists who’ve become predictable.<br />

That was one of the biggest compliments I’ve ever<br />

gotten.<br />

How important is acknowledgement?<br />

Very. I don’t think I could be the kind of artist that<br />

only creates without showing it to an audience. I’m<br />

Is it important that people like your work?<br />

I’m quite sensitive about it but it doesn’t guide me.<br />

Otherwise I would still be doing what I did 5 years<br />

ago. But I do feel good when people like my work.<br />

When I’m in my studio I’m on such a different planet<br />

that there’s not a thought in my mind about pleasing<br />

my viewers. However, I find showing my work in a<br />

gallery pretty stressful. You’ve given it your very best<br />

and all of a sudden people have an opinion about<br />

what you’ve been doing. It’s very confrontational<br />

stepping from your studio into a place where all of a<br />

sudden you’ve become someone with the intention<br />

of doing business. I think the art world has evolved<br />

in such a way that it’s necessary to step fully into the<br />

process of both creating and presenting. And since<br />

I’m very bad at the business side of things, I’m very<br />

happy that I have a gallery that takes care of this.<br />

When did you start calling yourself an artist?<br />

I still don’t. It feels weird. I always say I’m a sculptor.<br />

I think that covers it. This is a conversation I often<br />

have with my students: it’s the difference between<br />

being an artist and artistic practice. I don’t think it’s<br />

the same thing. For me, being part of the art world<br />

is called artistic practice, which doesn’t necessarily<br />

mean that you are an artist. Obviously I want to be<br />

part of that world, yet I don’t want to be swayed by<br />

it. It’s not what makes you an artist.<br />

I don’t often read about or hear you explain your<br />

work. Why not?<br />

I always feel that it doesn’t matter. That it isn’t<br />

necessary. I find what people say or write about my<br />

work more appealing. Although often surprising, I<br />

find someone else’s interpretation very interesting<br />

to think about, as opposed to when I talk about it<br />

myself. I don’t have the feeling that me talking about<br />

it adds any value. Maybe it’s because explaining<br />

your work ends the conversation. I like people to<br />

experience what they think and feel for themselves.<br />

Art opens people’s minds. When I started at the<br />

academy I found that it made me wiser, more<br />

grounded. And going to a museum often has a very<br />

big influence on the way I think. But this is what<br />

it does to me personally. When it comes to other<br />

017

people I do hope that my work makes people think,<br />

that it has a certain impact on how someone sees<br />

the world.<br />

Does art have to be socially relevant?<br />

There are always issues popping up along the way but<br />

my first reaction would be to say no. Not necessarily.<br />

Someone can view a piece of art as ‘just’ appealing.<br />

It’s not easy to say that nowadays, but I do believe<br />

that. However, a good work of art mostly contains<br />

all those qualities. Depending on the place and time<br />

where it’s created. It’s significance can even grow,<br />

becoming symbolic over time. For me it’s more<br />

important to make a balanced work than to make<br />

a point. Beyond the aesthetics, it’s important that<br />

the image is accurate. Like a painter who finds his<br />

balance with color, or a musician finding the right<br />

notes. For me it’s playing with forms and shapes.<br />

How does it feel to live with another artist?<br />

Honestly, I cannot imagine not living with an artist.<br />

If you’re together for more than <strong>20</strong> years, like we<br />

are, you grow together towards new things. You<br />

experience transformation together. Also, I couldn’t<br />

do without his feedback. I don’t like to have people<br />

in my studio when I am working, but it’s very<br />

important that Nick drops in because he instantly<br />

feels what I’m doing. Often it’s about the little<br />

things, but it’s easy for us to see what can make the<br />

other one’s work stronger. And because we know<br />

each other’s work through and through, it becomes<br />

very intuitive. His influence is never far. And the<br />

other way around.<br />

What makes you most happy?<br />

Being with Nick and sculpting. Because that’s what<br />

I do best. The former is about love and what we are<br />

doing together, how we are exploring other countries<br />

and our work. The things we are experiencing and<br />

how we turn that into works of art. The latter makes<br />

me extremely happy in a very intense manner, but<br />

it can equally make me very unhappy. I was raised<br />

very strictly, so considering my upbringing it’s not<br />

evident that I would have become a sculptor. I had<br />

to fight pretty hard to be able to do what I am doing<br />

now, so it must be very important. Otherwise I<br />

would have given up very easily. It’s both an urgency<br />

and an emergency.<br />

www.basealphagallery.be<br />

021

faryda<br />

moumouh<br />

text jf. pierets<br />

023

Why choose photography?<br />

Since I was young I was already drawing, watching,<br />

registering details from the things I saw. It was an urge<br />

and I had the feeling I was chosen by a visual language,<br />

which I pursued. I went to art school when I was 14 and<br />

it made me discover a cultural world that was alien to<br />

me. It opened the doors in my head and in my heart.<br />

Photography was love at first sight. What scared me in<br />

the beginning was the technicality of a camera. When<br />

I went to school cameras were still analogue. So you<br />

had to get going with diaphragms and shutter speeds.<br />

However, what I found very liberating was the speed<br />

of the medium. When I was a child I wanted to capture<br />

every detail of an insect but I had to do it before it was<br />

gone. Now I could just take a picture of everything that<br />

caught my eye. It was that directness, that velocity that<br />

got me hooked.<br />

What inspires you?<br />

I get inspired by society and the context in which I find<br />

myself. I’m not necessarily talking about politics, but<br />

we all find ourselves in a societal context in which you<br />

are free to respond or not. And if something triggers<br />

me, I have to act accordingly. It leads to a photographic<br />

series anticipating religion, or headscarves, or ethnicity.<br />

Those aren’t my themes per se, but I can’t ignore<br />

something that’s omnipresent. I call it philosophical<br />

image processing. My antennas are always on alert<br />

for images, words I read or hear, that can bring me<br />

towards a new interpretation. Inspiration is everywhere.<br />

I write everything down in little notebooks so I can<br />

start researching whenever something stays with me.<br />

Sometimes I call myself a philographer. A philosopher<br />

who meets a photographer.<br />

You are reading and seeing a lot. How do you decide<br />

what to take and what to leave behind?<br />

Most of the time I think and work on one theme, quote<br />

or story per year. That’s the starting point to frame and<br />

identify what I think and feel. I research, read, make<br />

sketches, and look for other sources that connect with<br />

the initial thought. If you look at my work process<br />

you’d think I’m a painter or a drawer because I collect<br />

thousands of images to filter and to support the result.<br />

I call this work in progress ‘photographic drawing’.<br />

When I’ve gathered enough information, I unleash my<br />

intellect, my logic reasoning and continue in a purely<br />

visual manner. The images themselves lead me towards<br />

the final result. Which is both analytic and visual. I always<br />

trust my heart to lead me to where I’m supposed to go.<br />

Can you talk me through one of your latest series?<br />

I re-read ‘The stranger’ by Albert Camus and it got me<br />

thinking about being the stranger versus being strange.<br />

Which is a very vague concept. I started photographing<br />

in Antwerp’s typical concentrated migrant areas but that<br />

turned out to be the wrong approach. Documentary<br />

is not my course. Then I thought about registering the<br />

reflection of those worlds. The reflections in mirrors, in<br />

shop windows, etc. to capture the thought that people<br />

are always judging the first layer of what they see. So<br />

instead of creating a linear sequence, I put the layers<br />

on top of each other to make a dialogue between the<br />

different pictures. In the end you have a strange image,<br />

consisting of multiple reflections of a strange world.<br />

They almost look like paintings. So it started with a book<br />

by Camus and I ended up here. It’s unpredictable. I never<br />

know where I will end up.<br />

Do you aim to keep your work recognizable? And is<br />

that necessary?<br />

When I’m photographing I’m not thinking about my<br />

specific visual language. And if it’s connected to my<br />

other work. However, I think my intuition is a constant<br />

guidance which, unconsciously, makes the images<br />

correspond with one another.<br />

How do you see your evolution?<br />

In the beginning my way of working was a bit too<br />

noncommittal. My way of capturing an image<br />

happened a bit too spontaneously. Over time this<br />

evolved into a more philosophical and conceptual<br />

manner. Whereas now I make a combination of those<br />

two styles. Conceptual but intuitive. I feel this course is<br />

the most accurate and closest to who I am as an artist. I<br />

feel very much at home with what I am doing.<br />

Ai Weiwei, Joseph Beuys and Marina Abramovic are 3<br />

of your heroes. What binds them together?<br />

Activism. And the freedom they claim to express their<br />

minds. Art doesn’t necessarily have to be activism.<br />

Personally, I find that social engagement always adds<br />

an extra value to the work or to the artist. I find what Ai<br />

Weiwei does from his context very important; his search<br />

for a full-blown democracy, the right to have an opinion<br />

and how he communicates that to the world. Activism<br />

depends on the context though. For me there’s a nuance<br />

between activism and social awareness. In my work it’s<br />

a social notion with lots of room for interpretation. If<br />

I were an activist, I would have to express my work in<br />

a more targeted and concrete manner. But I like my<br />

024

028<br />

‘Art gives a more added<br />

value to my life than<br />

religion. I don’t need to<br />

listen to a human invention.<br />

I’d rather listen to myself in<br />

everything that I do.’

work to act as a window through which I can inspire a<br />

dialogue. It obviously has its community themes but<br />

it’s more in a societal - than an activist context.<br />

And what about religion?<br />

Art has a more added value to my life than religion. I<br />

don’t need to listen to a human invention. I’d rather<br />

listen to myself in everything that I do.<br />

Do you identify with your work?<br />

Very much so. Being an artist defines my identity more<br />

than my background or roots. I’m an individualist and<br />

an existentialist. The notion that I am here and that<br />

I’m allowed to be here gives me the permission to<br />

claim my existence. That kind of freedom is almost<br />

sacred. As a teenager I found a lot of comfort in Sartre.<br />

It brought me the awareness that I exist, which has<br />

been a guidance throughout my life and has been my<br />

primary motive ever since. Not only as an artist but<br />

also as a human being. Let everybody be.<br />

Do you address certain topics in your work in order<br />

to have people ask questions?<br />

It depends on the question. For example, I constantly<br />

get asked where I’m from and it disturbs me that<br />

my ethnicity always takes the upper hand. I know<br />

it’s because of how I look and because of my name,<br />

but sometimes I just want to be. I want to talk about<br />

my work, about what I think. However, before I can<br />

do that, I always have to explain where I come from.<br />

I believe we have to accept that the world and our<br />

society is colored, but we don’t always need to talk<br />

about it. Because it always makes you ‘the other’.<br />

How about your place in the art scene?<br />

There are moments when I would like to have more<br />

public recognition for my work. But I’m very sensitive<br />

when people contact me when they need a female<br />

artist, a foreign artist, or both. Work by artist Charif<br />

Benhelima for example is exposed all over the world.<br />

Everybody talks about the strong visual language<br />

of his pictures which transcends his Moroccan-ness.<br />

His work goes beyond needing an excuse to have an<br />

ethnic artist in your collection. It’s just great work.<br />

And that’s what matters. Only with that kind of<br />

mentality can you get an exact reflection of the world<br />

in a museum or a gallery. And that’s what art is all<br />

about, isn’t it?<br />

www.faryda.com<br />

033

22

Next to offering you this brand-new edition of <strong>Et</strong> <strong>Alors</strong>? <strong>Magazine</strong>, we also wanted to share our new artwork with you:<br />

Out of the194 countries in the world, only 22 recognise and provide legal same-sex marriage. When saying these numbers out<br />

loud, we found that most people are not aware of this fact, so we have created a positive artwork that celebrates the countries<br />

that do allow it, while highlighting an issue that still needs work.<br />

As female artist duo & lovers JF. Pierets, we will get married in every country that recognises same-sex marriage. Starting off<br />

coming September <strong>20</strong>17 in New York. A camera crew will follow us over the 18 month course of the performance to later create<br />

a 50-minute making-of documentary. In <strong>20</strong>19 the art/video installation of “22” will be exhibited for the first time. A book with all<br />

our adventures will be released later that year.<br />

At the current rate we will reach global recognition of same-sex marriage in the year 2142. That’s 125 years from now so let’s see<br />

if they can get it to go a bit faster.<br />

www.22theproject.com<br />

www.jfpierets.com

© Gazelle Paulo

jorge<br />

clar<br />

037

We caught up with poet and performance artist<br />

Jorge Clar in his home in New York, and talked about<br />

words, sounds, and image. An ideal for living.<br />

Initially, you came to New York because you<br />

wanted to be close to the disco scene.<br />

That was the main reason. While growing up in<br />

Puerto Rico, I spent my time daydreaming and<br />

playing records. I became enthralled with the layers<br />

of sound in disco—the music became medicine.<br />

Everything about the genre, from the quality of<br />

the recordings to the way the arrangements are<br />

structured—featuring classical strings and horns,<br />

electronic textures, and rhythm—is alchemical.<br />

Disco pulled me through my adolescence. A few days<br />

after moving to New York in the fall of 1987, I went<br />

to the closing of the Paradise Garage discotheque.<br />

Larry Levan’s musical selections, and Richard Long’s<br />

sound system, were so mind blowing. The clubbers<br />

danced with such freedom and expressiveness—I<br />

knew right there and then I was home. I had gone<br />

to the Garage with Jesse Díaz, my first roommate<br />

in New York, with whom I had spent many summers<br />

in Puerto Rico, hanging out in discos and constantly<br />

listening to music. Through him, I developed a love<br />

for dancing and pulling looks together. In the early<br />

90s, I would meet DJ Freddy Turner, with whom I<br />

would write record reviews on house music 12-inch<br />

singles for underground music magazines, in the<br />

process meeting many of my heroes in music, like<br />

David Morales, Kerri Chandler and “Little” Louie<br />

Vega.<br />

When did you start writing poetry?<br />

I always loved books, and ever since I started reading<br />

authors like Borges, Ginsberg, and especially<br />

the short story A Clean, Well-Lighted Place by<br />

Hemingway, I knew I had to write poems. I remember<br />

reading Howl and thinking it was like my stream of<br />

consciousness. So I sat down on an old cast iron<br />

typewriter my father had given me and started to<br />

write, imagining myself a tape recorder of phrases<br />

and sounds I heard. My first poetry collection was<br />

called In a Singapore Hotel Room. I imagined myself<br />

as Somerset Maugham in the Raffles Hotel, which<br />

I had visited during a summer vacation. This was<br />

one of the first instances in which I was inhabiting a<br />

different character in a work of art, something that<br />

continues to this day in my performances. Through<br />

poetry—and through making cassette mix tapes,<br />

which to me were like building blocks of sound<br />

and words—it became easier to make friends and<br />

demonstrate who I was. I was a very shy only child,<br />

and mostly related to adults, until I decided I wanted<br />

to be friends with more of my classmates. Initially, I<br />

imitated the style and idioms of all that surrounded<br />

me, trying to fit in. But I soon realized the more<br />

I delved into my eccentricities, the more I had to<br />

share. After graduating from Syracuse University,<br />

where I studied Newspaper Writing, I eventually<br />

started combining between performance and<br />

poetry readings. People enjoyed the extra aspect<br />

of showmanship. A few years later, in New York,<br />

I worked at Penguin Books and started to come<br />

together with a group of friends. My friend Douglas<br />

Rothschild invited me to read at mythical places like<br />

the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. We would organize<br />

salons or read at people’s houses. My friend, the<br />

playwright Adam Rapp, would perform as a “human<br />

prop” with me. Those were formative years. Living<br />

with painter roommates Alberto Álvarez, and later<br />

Michael Brown—who still shares an apartment with<br />

me—has honed my eye for visuals and the notion of<br />

what makes a painting work. Hanging out with my<br />

college friend Paul Weinstein, with whom I would<br />

spend every Friday night and Saturday morning in<br />

his Park Slope apartment, focused my appreciation<br />

of great graphic design, modernist radios and<br />

electronic equipment, new wave music, and all sorts<br />

of collectibles.<br />

What else did you learn during those days?<br />

When my father passed away, I spent 7 years in Puerto<br />

Rico taking care of my mom. It was wonderful to<br />

relate to her as an adult and also explore other sides<br />

of my personality. I became the perfect homemaker<br />

and sometimes, when I would see objects from<br />

my life in New York, I would wonder where that<br />

person had gone. Eventually, I was offered a job at<br />

a marketing firm back in the city and mom was well<br />

enough to stay with a caregiver. I returned to living<br />

in New York full time. At a party, I met my friend<br />

Dominic Vine, and he introduced me to the Radical<br />

Faeries, a grassroots countercultural movement<br />

seeking to redefine queer consciousness through<br />

self-exploration. They were founded as a reaction to<br />

gay culture towards the end of the 70s. Back then,<br />

there was an emphasis on a ‘clone’ aesthetic, which<br />

presumed a masculine stance and set of rules. The<br />

faeries, on the other hand, established sanctuaries<br />

038

© Ron Amato

040<br />

‘I get the feeling<br />

that people are way<br />

more focused now on<br />

creating, expressing<br />

their freedom and<br />

celebrating who they<br />

are. It’s almost like a<br />

statement.’

© Dietmar Busse

© Dietmar Busse

‘You’re taught to<br />

be happy when<br />

you have achieved<br />

something, but I<br />

think it’s of upmost<br />

importance to be<br />

happy—in other<br />

words, to have a<br />

generalized sense<br />

of wellbeing—and<br />

enjoy the process<br />

as you go along.’<br />

in rural areas where men could explore aspects of<br />

their femininity. Becoming involved with them was<br />

a milestone in my life. I explored questions about<br />

relationships, sexuality and freedom. I discovered<br />

there is no “one size fits all” to relationships, for<br />

instance. They can be endlessly customized beyond<br />

paradigms like ‘husband’ or ‘boyfriend.’ Also, it was<br />

around this time that iPhones came into the scene,<br />

facilitating the capability of taking photos on the<br />

go. Dominic photographed me constantly, and we<br />

became collaborators in photo, writing and mix CD<br />

projects.<br />

You’ve come a long way. How do you look back?<br />

When I was little, I imagined myself on a dance<br />

floor like the one in Saturday Night Fever (I actually<br />

did visit the dance floor featured in the movie one<br />

Halloween, when my friend Katsumi Miki and I went<br />

to the now extant Spectrum disco in Bay Ridge,<br />

where the movie was filmed…I danced to Madonna’s<br />

“Vogue” on its wonderful lights and cried), moving<br />

to the rhythm of disco music and being exactly in the<br />

moment. I imagined myself in a sort of monumental<br />

stasis, frozen in ecstatic bliss. It heartens me that<br />

everything I envision actually manifests. It all<br />

becomes true. In my dreams, I wanted to interact<br />

with other artists, have lots of records and enjoy life<br />

everyday—and here I am.<br />

So you’ve found your peers?<br />

Yes, I think we’re on the brink of a movement.<br />

I’m humble and grateful to be a part of it all and<br />

facilitate connections between people, supporting<br />

each other and working together. For example, I<br />

never considered myself someone who draws, and<br />

now I do so in a spirit of play and discovery. At my<br />

friend Joel Handorff’s place, Kelly Bugden, Scooter<br />

LaForge, Van Wifvat and I often get together to<br />

draw, and more friends like Rafael Sánchez, Gail<br />

Thacker and Gerardo Vizmanos also join in. We like<br />

to call these sessions “The Magic Mirror,” where<br />

we are all reflections of each other. Johnny Rozsa<br />

will often serve as a model. Connections happen<br />

serendipitously. I met Bubi Canal when he came to<br />

see a performance I did with José Joaquín Figueroa.<br />

That meeting led to much collaboration, and I’ve<br />

played characters in both Bubi’s and Jose’s video<br />

art. Bubi and I meet almost daily to discuss social<br />

media and work on projects at Little Skips, a café in<br />

Bushwick which we call “the office.” I commissioned<br />

a t-shirt with a painting of Allen Ginsberg from<br />

Scooter years ago, and that dialogue led to countless<br />

painted garments, which I often wear during my<br />

performances—both live and in photos—and often<br />

within the context of his shows. I wrote poems about<br />

the atmosphere of his painting process and they<br />

were included in the catalog for one of his shows.<br />

Dietmar Busse invited me to his apartment to take<br />

my portrait, and from there he has taken many<br />

photos which are so dear to me. In Van’s house in<br />

Ocean Grove, New Jersey, a Victorian cottage full<br />

of good spirit (I think I lived there in a previous life),<br />

many of us get together and make drawings and<br />

take photos. The greatest beauty of all this is that<br />

through creativity, we all have become dear friends<br />

who participate in a constant conversation that<br />

generates new realities.<br />

What do you think of the political climate of the<br />

United States at the moment?<br />

There’s a lot of political anxiety nowadays. The<br />

day after the last election almost felt the same as<br />

the day after 9/11. There was this stillness, based<br />

on anger and pessimism. A lot of people felt very<br />

scared and wanted to leave the country, thinking,<br />

for instance, that gays would be more marginalized<br />

as a minority group. However, I get the feeling that<br />

people are way more focused now on creating,<br />

expressing their freedom and celebrating who they<br />

043

044

© Dietmar Busse

© Van Wifvat

are. It’s almost like a statement. Everything has<br />

a political implication. It makes art stronger and it<br />

is going beyond the framework of what has been<br />

before. It’s getting richer and more focused. And it<br />

comes straight from the heart. Like an act of magic.<br />

Now more than ever this whole idea of following<br />

your intuition takes everything to a different level.<br />

Do you know the saying that the darkest part of<br />

the tunnel is just before the end? Well, I think that’s<br />

where we are right now.<br />

And your personal work?<br />

I have my blog, which is basically a photoperformance<br />

as well as a writing project. It’s both<br />

an archive of all the personas in my imagination as<br />

well as a documentation of the artistic community.<br />

I write stories about what I’m wearing on certain<br />

days. I explain where and with whom I was when I<br />

found a particular shirt, for example. What we were<br />

talking about at that moment. What caught my<br />

eye and convinced me to buy. Or about the friend<br />

who gave me a pair of pants —what he is doing<br />

with his life, where he comes from and why he felt<br />

he needed to offer me that present. The stories<br />

go into the details of what happens every day, in<br />

Proustian fashion. My biggest influences in writing<br />

are Andy Warhol, 80’s nightlife chronicler Stephen<br />

Saban, Charles Baudelaire and Bill Cunningham, the<br />

late New York Times fashion journalist. On the blog<br />

photos, I’m often wearing clothes made by friends,<br />

which adds an extra layer to the narrative. I become<br />

a mannequin—or a canvas, if you will—for their<br />

artwork. The images connect people and events in<br />

daily life. I’m weaving together a world that seems<br />

recognizable, and yet has a dreamlike quality. Jorge<br />

Clar Diary is a never-ending novella.<br />

You make time capsules.<br />

Yes, time documents, literally and figuratively.<br />

Like a diary. I’ve always loved diaries because of<br />

the way they talk about the small things. I love the<br />

idea of giving these tiny details their moment in the<br />

spotlight. By doing so, even the most banal thing<br />

can become very meaningful. It’s a pure reflection of<br />

my thinking process.<br />

Tell me about your work on physical<br />

transformation.<br />

When I first came out as a gay man, I was travelling<br />

through Israel. I felt very comfortable there, mainly<br />

because I was in a different environment. Being<br />

in Jerusalem, I could feel the place was very<br />

charged. Generally, people go to this city with<br />

much anticipation, due to whatever significance<br />

they give to to the place, which makes for a<br />

particular energy. The only other place that has<br />

the same energy is New York City, as people tend<br />

to come here with a specific purpose in mind. In<br />

Israel, I felt like I could see things within a sense<br />

of protection. Up until that point, I had repressed<br />

my attraction to men, and it was in Tel Aviv that<br />

I had an epiphany and was through with denial.<br />

I “came out” to myself. A veil lifted, and after<br />

that I transformed very quickly. It wasn’t as much<br />

about sexual liberation, but more about freedom<br />

of expression. And one of my main tools of<br />

expression is through clothing. I’ve always been<br />

enamored by an abstract sense of glamour and the<br />

epiphanies I often have late at night, when I listen<br />

to music. By accessing that magic and expressing<br />

it through clothes, I create subtle characters that<br />

deliver a message.<br />

People react to this expression. I say this very<br />

humbly and with much gratitude: sometimes I am<br />

told I give hope. That my work inspires or cheers<br />

up the day. I think that’s so amazing. I love walking<br />

down the street and having someone smile at me.<br />

When one wears even the most surrealistic outfit<br />

with conviction, there is almost a air of reverence.<br />

You sound very spiritual. Are you?<br />

I feel the universe has always taken care of me.<br />

I’ve been through hardships, but in the end they<br />

made me strong enough to now enjoy every<br />

moment. You’re taught to be happy when you<br />

have achieved something, but I think it’s of<br />

upmost importance to be happy—in other words,<br />

to have a generalized sense of wellbeing—and<br />

enjoy the process as you go along. If you follow<br />

your intuition and are a kind person, things<br />

become way easier to navigate. Art becomes very<br />

helpful, bringing forth a meditative state. When<br />

your work is based on play, more possibilities<br />

come to light: you can do and be more. I strive to<br />

think constructively, and manage my emotions<br />

consistently. When I do what feels good, I know<br />

I’m on the right path. I can then manifest with<br />

utmost efficiency.<br />

www.jorgeclar.com<br />

047

ernard<br />

perlin<br />

text jf. pierets<br />

049

Bernard Perlin (1918-<strong>20</strong>14) was an extraordinary<br />

figure in twentieth century American art and gay<br />

cultural history. An acclaimed artist and sexual<br />

renegade who reveled in pushing social, political,<br />

and artistic boundaries, his work regularly<br />

appeared in popular magazines in the 1940s, ‘50s,<br />

and ‘60s; was collected by Rockefellers, Whitneys,<br />

Astors, and Andy Warhol; and was acquired by<br />

major museums, including the Smithsonian, the<br />

Museum of Modern Art, and the Tate. In One-Man<br />

Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied<br />

life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding<br />

adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holdsbarred<br />

interviews with the artist, candid excerpts<br />

from Perlin’s unpublished memoirs, never-beforeseen<br />

photos, and an extensive selection of Bernard<br />

Perlin’s incredible public and private art.<br />

One-Man Show: The Life and Art of Bernard<br />

Perlin has been named a <strong>20</strong>17 Stonewall Honor<br />

Book by the American Library Association, and is<br />

a Lambda Literary Award Finalist.<br />

What triggered you to write this book?<br />

I discovered Bernard and his amazing artwork<br />

through my great interest in the illustrious gay<br />

social and artistic circle that surrounded the<br />

legendary photographer George Platt Lynes in<br />

the 1930s through 1950s. Bernard was an intimate<br />

member of this great New York gay “cabal,” as he<br />

called it, whose members and visitors included<br />

such artists and literary such figures as Somerset<br />

Maugham, and Christopher Isherwood. Bernard<br />

Perlin was the last living member of this remarkable<br />

company, then in his early nineties, and so I wrote<br />

him. He responded with a friendly phone call that<br />

led to another and another and ultimately to an<br />

invitation to his home in Connecticut. And so<br />

began our close friendship and the unexpected<br />

journey towards this book.<br />

Was it important to write this book, aside from<br />

your personal connection with Perlin?<br />

First and foremost, I felt a great sense of<br />

commitment to getting Bernard Perlin’s<br />

extraordinary artwork seen again. But as I began<br />

to learn more about his equally extraordinary<br />

life, I knew the incredibly compelling story of this<br />

unsung gay artist-hero had to be told somehow,<br />

and as much as possible in his own colorful,<br />

unfiltered way.<br />

As an art connoisseur, what attracts you to his<br />

work?<br />

Bernard was a beguiling storyteller - not only<br />

in conversation, but also in his art. Every Perlin<br />

painting tells a unique story. I’m particularly drawn<br />

to his work that can be classified as “magic realism,”<br />

in which he interjected unexpected or magical<br />

elements into his examination of “real” situations<br />

or objects or figures. I always find his perspective<br />

an interesting one to consider. In terms of subject<br />

matter, I really love Bernard’s “Night Pictures,” a<br />

series of paintings depicting the swinging “cocktail<br />

culture” of 1950s New York City jazz clubs, street<br />

dances, and underground gay bars. The latter were<br />

very daring works for him to publicly show when he<br />

did, but for Bernard they were just further efforts<br />

to depict the full “normal” range of people seeking<br />

connection with one another.<br />

He was openly gay in the 1930’s. How did that<br />

work out?<br />

While he was very conscious of his sexuality and<br />

embraced it from a very young age, it wasn’t really<br />

until he went to art school in 1935 in New York that<br />

he found a thriving underground gay culture that<br />

welcomed him and he easily fit into. He was 16 years<br />

old at the time. From that point on, Bernard chose<br />

to also live his life “above ground” as a fearlessly<br />

openly gay man – doing so during a fearfully closed<br />

period in our recent history. It’s remarkable now to<br />

consider some of the real risks he faced, sometimes<br />

head on. He walked past a sign reading “no Jews<br />

allowed” into a department store in Nazi-occupied<br />

Danzig in 1938, bought a pair of Hitler Youth shorts,<br />

and then boldly walked around in them, as not only<br />

a young gay man, but a Jew. Equally remarkable<br />

was his attitude about being arrested in a Parisian<br />

bathhouse in 1951. In spite of being thrown into a<br />

large cage in the middle of a medieval courtroom,<br />

and tried in a language he didn’t understand while<br />

onlookers jeered, then being jailed without knowing<br />

how long he’d be held, Bernard just took it in his<br />

stride and thought it all a “great adventure.” He was<br />

similarly arrested in Florida and Virginia for “behavior<br />

against public decency,” posted bail, then skipped<br />

town and carried on undeterred with his cruising<br />

and bathhouse escapades. But certainly the most<br />

poignant story he shared with me was about his not<br />

wanting to fight in World War II, so he had to go to<br />

a psychiatrist, be declared a “mental degenerate”<br />

050

as a homosexual, and then present himself as such<br />

in front of the draft board. When we talked about<br />

this, Bernard confessed that he had long carried a<br />

sense of shame over what he perceived to be his<br />

cowardice about not going to war, when in fact it<br />

was an incredibly brave act to have publicly declared<br />

himself a homosexual in 1941. And of course, he<br />

then went on to fight the war anyway, but with his<br />

paintbrush, producing many now iconic images<br />

of World War II as a propaganda artist for the U.S.<br />

government and as a war-artist correspondent for<br />

Life magazine.<br />

Did you ask him about the most significant<br />

changes between being gay in the 1930’s and<br />

now?<br />

I did. It was very enlightening for me to learn<br />

that he had been able to so freely express his<br />

sexuality when he did – although it should also<br />

be considered where he did – in 1930s New York,<br />

which was somewhat less permissive than it had<br />

been during the 19<strong>20</strong>s, but yet allowed gay bars<br />

and gathering places to exist, as long as the police<br />

were paid off. Of course outside of New York, such<br />

open expression carried tremendous risk. As he<br />

explained it: “one was open but with a great sense of<br />

consciousness about it.” In the last couple of years of<br />

his life, he was delighted by the changes that were<br />

then accelerating for gay acceptance. The act of<br />

marrying his partner of 60 years was a tremendously<br />

important one for him. And they did it solely as<br />

a political statement, to add their number to the<br />

statistics. Although he had never been conflicted<br />

about being gay, Bernard certainly celebrated the<br />

fact that society was becoming less conflicted. Or so<br />

he hoped.<br />

You write about Perlin as a gay artist and you<br />

launched the book at a gay publishing company.<br />

Why is it important to accentuate this?<br />

The actual artwork should be left to the<br />

interpretation of the viewer, of course. We all see<br />

the world uniquely through the lens of our own<br />

experience and identity. For that reason, Bernard<br />

didn’t like having his work linked to a particular<br />

style, nor did he subscribe to any particular school of<br />

art. He wanted viewers to interpret his work in their<br />

own way, free of any pre-established definitions,<br />

but yet at the end, he did want them to know it was<br />

the work of a gay artist. That the great variety of<br />

‘Of course<br />

historically up to<br />

this point there<br />

has been limited<br />

gay imagery<br />

in mainstream<br />

art because it<br />

has not been a<br />

socially accepted<br />

expression. But<br />

I’m ever hopeful<br />

that that is<br />

changing.’<br />

human experience that he had depicted in his work<br />

– that a great variety of people had emotionally and<br />

intellectually responded to over seven decades – had<br />

all been recorded by a fellow human being who just<br />

happened to be gay. By a “variant” himself. It was an<br />

identity that he felt very proud of and committed to<br />

championing – to “normalizing” in a way, although<br />

there truly is no such thing as “normal.” He just<br />

hoped his viewers would allow and consider it, in the<br />

hopes it might expand their perception not only of<br />

his art, but also of our shared humanity.<br />

Does this have something to do with awareness?<br />

Showing that artists, movie stars, etc. can also be<br />

gay?<br />

Sure, as you bring the gay experience into the fold<br />

of the bigger human experience, it does “normalize”<br />

it. Just as I feel it’s important to consider whatever<br />

particular identity an artist embraces – whether that<br />

relates to their gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity,<br />

etc. – in the hope it will challenge and expand<br />

a viewer’s perspective on their art, but will also<br />

054

‘I feel it’s important to<br />

consider whatever particular<br />

identity an artist embraces –<br />

whether that relates to their<br />

gender, sexual orientation,<br />

ethnicity, etc. – in the hope it<br />

will challenge and expand a<br />

viewer’s perspective on their<br />

art, but will also influence<br />

how that viewer then sees<br />

the real world and lives<br />

happening around them.<br />

Ultimately, we are all human<br />

at the end of the day.’

influence how that viewer then sees the real world<br />

and lives happening around them. Ultimately, we<br />

are all human at the end of the day. Isn’t it wonderful<br />

that we can see things so differently? In fact, it’s<br />

important that we do. Considering that informs<br />

all of us about the wonderful variety of the human<br />

experience. And toward that end, Bernard found it<br />

very important to raise his hand and be amongst the<br />

counted as gay artists.<br />

Why do you think there is so little gay imagery in<br />

art history?<br />

That’s an interesting topic that Bernard and I<br />

actually spoke a lot about. A picture of two men or<br />

two women kissing isn’t actually a classical theme<br />

in art – “yet,” as Bernard would point out. Of course<br />

historically up to this point there has been limited<br />

gay imagery in mainstream art because it has not<br />

been a socially accepted expression. But I’m ever<br />

hopeful that that is changing. Bernard was in the<br />

vanguard of artists who were boldly depicting<br />

gay themes in their work several generations ago,<br />

and happily that mantle has been taken up in recent<br />

decades by more and more younger artists. It’s just<br />

a matter now of getting more of their work on the<br />

walls of mainstream museums to make that “yet” a<br />

reality.<br />

Page 48 The Shore, 1953<br />

Page 52 The Forest, 1956<br />

Page 55 B-29 Mechanics, 1945<br />

Page 56 The Gang, 1957<br />

Page 59 Spanish Steps, 1954<br />

Page 60 Hospital Corridor, 1961<br />

Page 62 Self Portrait, 1937<br />

Is that also something you aim for with your book?<br />

Absolutely. It’s empowering to have known this<br />

man who was at the vanguard of promoting that<br />

acceptance just by living his life openly and fully<br />

and refusing to compromise. I was so blessed to<br />

have learned from a fellow human being who had<br />

the ability and the courage to embrace and to<br />

dominate his life – a man who was fully occupied<br />

with living, loving, and leaving nothing unexplored<br />

that interested him. He found both in his life and<br />

his art what is at the heart of the fulfilled human<br />

experience: and that is, to live one’s life fully in one’s<br />

own way – authentically, and without apology. And<br />

so that is what is at the heart of this book, and why I<br />

felt Bernard’s story was an important one to share –<br />

not to provide an exact blueprint of how one should<br />

live one’s life, but to open a door to possibilities, and<br />

permission.<br />

www.bernardperlin.com<br />

www.discover.brunogmuender.com/one-manshow-bernard-perlin<br />

063

clark<br />

kent<br />

artwork jf. pierets

066

One of our favourite movie monologues is from<br />

David Carradine in Quinten Tarantino’s Kill Bill. Bill<br />

talks about Superman. How Superman wakes up in<br />

the morning as Superman and dresses into his alterego<br />

Clark Kent in order to blend in with us humans.<br />

His glasses and the business suit are a costume,<br />

whereas his cape with the big red “S” is his normal<br />

attire.<br />

Emerging from our daily reflection and the things<br />

we see around us, “Clark Kent” is an investigation<br />

into the disconnect between the gay identity<br />

and society’s parameters. A society filled with<br />

collective family aspirations and hetero normative<br />

imagery. Where gay advertisement is still rare and<br />

often considered offensive. We wondered how<br />

personalities form if you don’t have any role-models.<br />

And if you can construct a true identity when there is<br />

no familiarity in sight. Do you put on your Clark Kent<br />

costume, in order to fit in? Or not?<br />

Being gay, there is a lack of connection between who<br />

you are and what you see in the world around you.<br />

“Clark Kent” is a series that addresses this conscious<br />

and unconscious effect, and the inevitable need to<br />

reconstruct who you are.<br />

www.jfpierets.com<br />

067

068

069

‘Being gay, there is<br />

a lack of connection<br />

between who you<br />

are and what you see<br />

in the world around<br />

you. “Clark Kent” is a<br />

series that addresses<br />

this conscious and<br />

unconscious effect,<br />

and the inevitable<br />

need to reconstruct<br />

who you are.’

A global celebration of diversity.<br />

© <strong>20</strong>17 | www.etalorsmagazine.com