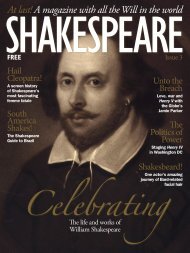

Shakespeare Magazine 13

Ian McKellen is the cover star of Shakespeare Magazine Issue 13. The great man talks about the challenges of playing King Lear, while Fiona Shaw explains Katherine from Taming of the Shrew and Patrick Stewart discusses Shylock. Also this issue, we look at the TV series that portrayed Shakespeare as a punk, and we delve into the sometimes horrific medical treatments of Shakespeare’s day. Graham Holderness tells us about The Faith of William Shakespeare, while Jem Bloomfield investigates Shakespeare and the Psalms Mystery. We also have excellent interviews with Sam White of Shakespeare in Detroit and Mya Gosling of Good Tickle Brain. Not forgetting our round-up of recent Shakespeare books and our essential guide to studying Shakespeare!

Ian McKellen is the cover star of Shakespeare Magazine Issue 13. The great man talks about the challenges of playing King Lear, while Fiona Shaw explains Katherine from Taming of the Shrew and Patrick Stewart discusses Shylock. Also this issue, we look at the TV series that portrayed Shakespeare as a punk, and we delve into the sometimes horrific medical treatments of Shakespeare’s day. Graham Holderness tells us about The Faith of William Shakespeare, while Jem Bloomfield investigates Shakespeare and the Psalms Mystery. We also have excellent interviews with Sam White of Shakespeare in Detroit and Mya Gosling of Good Tickle Brain. Not forgetting our round-up of recent Shakespeare books and our essential guide to studying Shakespeare!

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

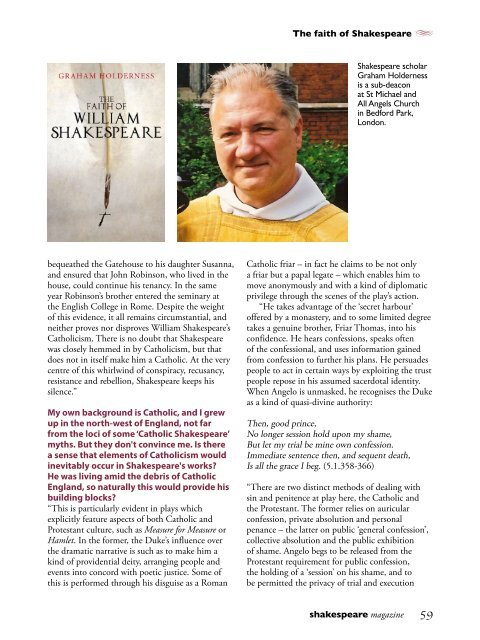

The faith of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> scholar<br />

Graham Holderness<br />

is a sub-deacon<br />

at St Michael and<br />

All Angels Church<br />

in Bedford Park,<br />

London.<br />

bequeathed the Gatehouse to his daughter Susanna,<br />

and ensured that John Robinson, who lived in the<br />

house, could continue his tenancy. In the same<br />

year Robinson’s brother entered the seminary at<br />

the English College in Rome. Despite the weight<br />

of this evidence, it all remains circumstantial, and<br />

neither proves nor disproves William <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

Catholicism. There is no doubt that <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

was closely hemmed in by Catholicism, but that<br />

does not in itself make him a Catholic. At the very<br />

centre of this whirlwind of conspiracy, recusancy,<br />

resistance and rebellion, <strong>Shakespeare</strong> keeps his<br />

silence.”<br />

My own background is Catholic, and I grew<br />

up in the north-west of England, not far<br />

from the loci of some ‘Catholic <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’<br />

myths. But they don't convince me. Is there<br />

a sense that elements of Catholicism would<br />

inevitably occur in <strong>Shakespeare</strong>'s works?<br />

He was living amid the debris of Catholic<br />

England, so naturally this would provide his<br />

building blocks?<br />

“This is particularly evident in plays which<br />

explicitly feature aspects of both Catholic and<br />

Protestant culture, such as Measure for Measure or<br />

Hamlet. In the former, the Duke’s influence over<br />

the dramatic narrative is such as to make him a<br />

kind of providential deity, arranging people and<br />

events into concord with poetic justice. Some of<br />

this is performed through his disguise as a Roman<br />

Catholic friar – in fact he claims to be not only<br />

a friar but a papal legate – which enables him to<br />

move anonymously and with a kind of diplomatic<br />

privilege through the scenes of the play’s action.<br />

“He takes advantage of the ‘secret harbour’<br />

offered by a monastery, and to some limited degree<br />

takes a genuine brother, Friar Thomas, into his<br />

confidence. He hears confessions, speaks often<br />

of the confessional, and uses information gained<br />

from confession to further his plans. He persuades<br />

people to act in certain ways by exploiting the trust<br />

people repose in his assumed sacerdotal identity.<br />

When Angelo is unmasked, he recognises the Duke<br />

as a kind of quasi-divine authority:<br />

Then, good prince,<br />

No longer session hold upon my shame,<br />

But let my trial be mine own confession.<br />

Immediate sentence then, and sequent death,<br />

Is all the grace I beg. (5.1.358-366)<br />

“There are two distinct methods of dealing with<br />

sin and penitence at play here, the Catholic and<br />

the Protestant. The former relies on auricular<br />

confession, private absolution and personal<br />

penance – the latter on public ‘general confession’,<br />

collective absolution and the public exhibition<br />

of shame. Angelo begs to be released from the<br />

Protestant requirement for public confession,<br />

the holding of a ‘session’ on his shame, and to<br />

be permitted the privacy of trial and execution<br />

shakespeare magazine 59