Caribbean Beat — January/February 2018 (#149)

A calendar of events; music, film, and book reviews; travel features; people profiles, and much more.

A calendar of events; music, film, and book reviews; travel features; people profiles, and much more.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

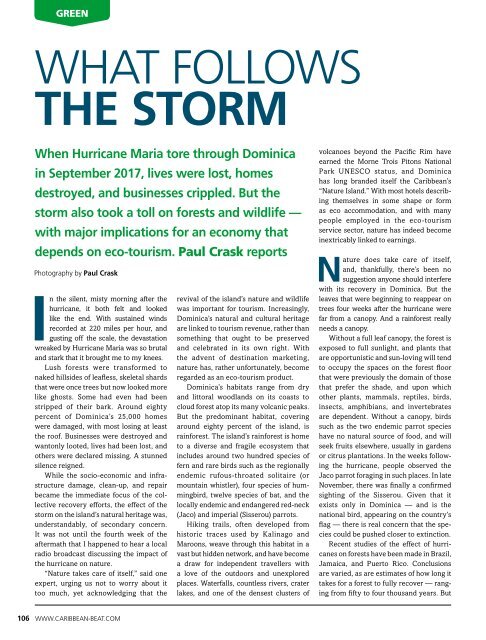

Green<br />

WhAT follows<br />

the storm<br />

When Hurricane Maria tore through Dominica<br />

in September 2017, lives were lost, homes<br />

destroyed, and businesses crippled. But the<br />

storm also took a toll on forests and wildlife <strong>—</strong><br />

with major implications for an economy that<br />

depends on eco-tourism. Paul Crask reports<br />

Photography by Paul Crask<br />

In the silent, misty morning after the<br />

hurricane, it both felt and looked<br />

like the end. With sustained winds<br />

recorded at 220 miles per hour, and<br />

gusting off the scale, the devastation<br />

wreaked by Hurricane Maria was so brutal<br />

and stark that it brought me to my knees.<br />

Lush forests were transformed to<br />

naked hillsides of leafless, skeletal shards<br />

that were once trees but now looked more<br />

like ghosts. Some had even had been<br />

stripped of their bark. Around eighty<br />

percent of Dominica’s 25,000 homes<br />

were damaged, with most losing at least<br />

the roof. Businesses were destroyed and<br />

wantonly looted, lives had been lost, and<br />

others were declared missing. A stunned<br />

silence reigned.<br />

While the socio-economic and infrastructure<br />

damage, clean-up, and repair<br />

became the immediate focus of the collective<br />

recovery efforts, the effect of the<br />

storm on the island’s natural heritage was,<br />

understandably, of secondary concern.<br />

It was not until the fourth week of the<br />

aftermath that I happened to hear a local<br />

radio broadcast discussing the impact of<br />

the hurricane on nature.<br />

“Nature takes care of itself,” said one<br />

expert, urging us not to worry about it<br />

too much, yet acknowledging that the<br />

revival of the island’s nature and wildlife<br />

was important for tourism. Increasingly,<br />

Dominica’s natural and cultural heritage<br />

are linked to tourism revenue, rather than<br />

something that ought to be preserved<br />

and celebrated in its own right. With<br />

the advent of destination marketing,<br />

nature has, rather unfortunately, become<br />

regarded as an eco-tourism product.<br />

Dominica’s habitats range from dry<br />

and littoral woodlands on its coasts to<br />

cloud forest atop its many volcanic peaks.<br />

But the predominant habitat, covering<br />

around eighty percent of the island, is<br />

rainforest. The island’s rainforest is home<br />

to a diverse and fragile ecosystem that<br />

includes around two hundred species of<br />

fern and rare birds such as the regionally<br />

endemic rufous-throated solitaire (or<br />

mountain whistler), four species of hummingbird,<br />

twelve species of bat, and the<br />

locally endemic and endangered red-neck<br />

(Jaco) and imperial (Sisserou) parrots.<br />

Hiking trails, often developed from<br />

historic traces used by Kalinago and<br />

Maroons, weave through this habitat in a<br />

vast but hidden network, and have become<br />

a draw for independent travellers with<br />

a love of the outdoors and unexplored<br />

places. Waterfalls, countless rivers, crater<br />

lakes, and one of the densest clusters of<br />

volcanoes beyond the Pacific Rim have<br />

earned the Morne Trois Pitons National<br />

Park UNESCO status, and Dominica<br />

has long branded itself the <strong>Caribbean</strong>’s<br />

“Nature Island.” With most hotels describing<br />

themselves in some shape or form<br />

as eco accommodation, and with many<br />

people employed in the eco-tourism<br />

service sector, nature has indeed become<br />

inextricably linked to earnings.<br />

Nature does take care of itself,<br />

and, thankfully, there’s been no<br />

suggestion anyone should interfere<br />

with its recovery in Dominica. But the<br />

leaves that were beginning to reappear on<br />

trees four weeks after the hurricane were<br />

far from a canopy. And a rainforest really<br />

needs a canopy.<br />

Without a full leaf canopy, the forest is<br />

exposed to full sunlight, and plants that<br />

are opportunistic and sun-loving will tend<br />

to occupy the spaces on the forest floor<br />

that were previously the domain of those<br />

that prefer the shade, and upon which<br />

other plants, mammals, reptiles, birds,<br />

insects, amphibians, and invertebrates<br />

are dependent. Without a canopy, birds<br />

such as the two endemic parrot species<br />

have no natural source of food, and will<br />

seek fruits elsewhere, usually in gardens<br />

or citrus plantations. In the weeks following<br />

the hurricane, people observed the<br />

Jaco parrot foraging in such places. In late<br />

November, there was finally a confirmed<br />

sighting of the Sisserou. Given that it<br />

exists only in Dominica <strong>—</strong> and is the<br />

national bird, appearing on the country’s<br />

flag <strong>—</strong> there is real concern that the species<br />

could be pushed closer to extinction.<br />

Recent studies of the effect of hurricanes<br />

on forests have been made in Brazil,<br />

Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. Conclusions<br />

are varied, as are estimates of how long it<br />

takes for a forest to fully recover <strong>—</strong> ranging<br />

from fifty to four thousand years. But<br />

106 WWW.CARIBBEAN-BEAT.COM