BCJ_WINTER18 Digital Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

END OF THE LINE<br />

SKAGIT SALVATION<br />

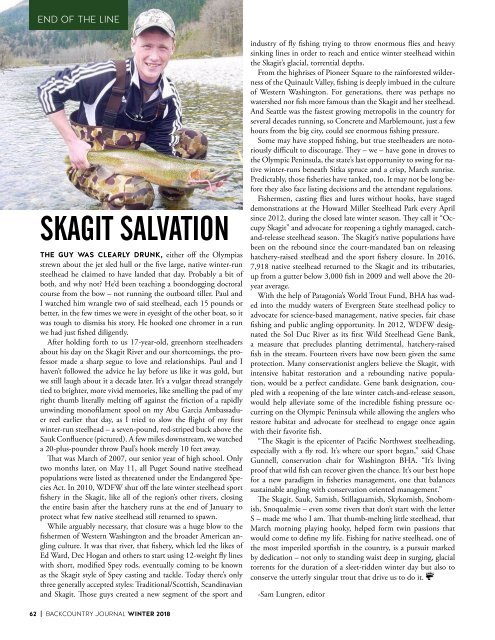

THE GUY WAS CLEARLY DRUNK, either off the Olympias<br />

strewn about the jet sled hull or the five large, native winter-run<br />

steelhead he claimed to have landed that day. Probably a bit of<br />

both, and why not? He’d been teaching a boondogging doctoral<br />

course from the bow – not running the outboard tiller. Paul and<br />

I watched him wrangle two of said steelhead, each 15 pounds or<br />

better, in the few times we were in eyesight of the other boat, so it<br />

was tough to dismiss his story. He hooked one chromer in a run<br />

we had just fished diligently.<br />

After holding forth to us 17-year-old, greenhorn steelheaders<br />

about his day on the Skagit River and our shortcomings, the professor<br />

made a sharp segue to love and relationships. Paul and I<br />

haven’t followed the advice he lay before us like it was gold, but<br />

we still laugh about it a decade later. It’s a vulgar thread strangely<br />

tied to brighter, more vivid memories, like smelling the pad of my<br />

right thumb literally melting off against the friction of a rapidly<br />

unwinding monofilament spool on my Abu Garcia Ambassaduer<br />

reel earlier that day, as I tried to slow the flight of my first<br />

winter-run steelhead – a seven-pound, red-striped buck above the<br />

Sauk Confluence (pictured). A few miles downstream, we watched<br />

a 20-plus-pounder throw Paul’s hook merely 10 feet away.<br />

That was March of 2007, our senior year of high school. Only<br />

two months later, on May 11, all Puget Sound native steelhead<br />

populations were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species<br />

Act. In 2010, WDFW shut off the late winter steelhead sport<br />

fishery in the Skagit, like all of the region’s other rivers, closing<br />

the entire basin after the hatchery runs at the end of January to<br />

protect what few native steelhead still returned to spawn.<br />

While arguably necessary, that closure was a huge blow to the<br />

fishermen of Western Washington and the broader American angling<br />

culture. It was that river, that fishery, which led the likes of<br />

Ed Ward, Dec Hogan and others to start using 12-weight fly lines<br />

with short, modified Spey rods, eventually coming to be known<br />

as the Skagit style of Spey casting and tackle. Today there’s only<br />

three generally accepted styles: Traditional/Scottish, Scandinavian<br />

and Skagit. Those guys created a new segment of the sport and<br />

industry of fly fishing trying to throw enormous flies and heavy<br />

sinking lines in order to reach and entice winter steelhead within<br />

the Skagit’s glacial, torrential depths.<br />

From the highrises of Pioneer Square to the rainforested wilderness<br />

of the Quinault Valley, fishing is deeply imbued in the culture<br />

of Western Washington. For generations, there was perhaps no<br />

watershed nor fish more famous than the Skagit and her steelhead.<br />

And Seattle was the fastest growing metropolis in the country for<br />

several decades running, so Concrete and Marblemount, just a few<br />

hours from the big city, could see enormous fishing pressure.<br />

Some may have stopped fishing, but true steelheaders are notoriously<br />

difficult to discourage. They – we – have gone in droves to<br />

the Olympic Peninsula, the state’s last opportunity to swing for native<br />

winter-runs beneath Sitka spruce and a crisp, March sunrise.<br />

Predictably, those fisheries have tanked, too. It may not be long before<br />

they also face listing decisions and the attendant regulations.<br />

Fishermen, casting flies and lures without hooks, have staged<br />

demonstrations at the Howard Miller Steelhead Park every April<br />

since 2012, during the closed late winter season. They call it “Occupy<br />

Skagit” and advocate for reopening a tightly managed, catchand-release<br />

steelhead season. The Skagit’s native populations have<br />

been on the rebound since the court-mandated ban on releasing<br />

hatchery-raised steelhead and the sport fishery closure. In 2016,<br />

7,918 native steelhead returned to the Skagit and its tributaries,<br />

up from a gutter below 3,000 fish in 2009 and well above the 20-<br />

year average.<br />

With the help of Patagonia’s World Trout Fund, BHA has waded<br />

into the muddy waters of Evergreen State steelhead policy to<br />

advocate for science-based management, native species, fair chase<br />

fishing and public angling opportunity. In 2012, WDFW designated<br />

the Sol Duc River as its first Wild Steelhead Gene Bank,<br />

a measure that precludes planting detrimental, hatchery-raised<br />

fish in the stream. Fourteen rivers have now been given the same<br />

protection. Many conservationist anglers believe the Skagit, with<br />

intensive habitat restoration and a rebounding native population,<br />

would be a perfect candidate. Gene bank designation, coupled<br />

with a reopening of the late winter catch-and-release season,<br />

would help alleviate some of the incredible fishing pressure occurring<br />

on the Olympic Peninsula while allowing the anglers who<br />

restore habitat and advocate for steelhead to engage once again<br />

with their favorite fish.<br />

“The Skagit is the epicenter of Pacific Northwest steelheading,<br />

especially with a fly rod. It’s where our sport began,” said Chase<br />

Gunnell, conservation chair for Washington BHA. “It’s living<br />

proof that wild fish can recover given the chance. It’s our best hope<br />

for a new paradigm in fisheries management, one that balances<br />

sustainable angling with conservation oriented management.”<br />

The Skagit, Sauk, Samish, Stillaguamish, Skykomish, Snohomish,<br />

Snoqualmie – even some rivers that don’t start with the letter<br />

S – made me who I am. That thumb-melting little steelhead, that<br />

March morning playing hooky, helped form twin passions that<br />

would come to define my life. Fishing for native steelhead, one of<br />

the most imperiled sportfish in the country, is a pursuit marked<br />

by dedication – not only to standing waist deep in surging, glacial<br />

torrents for the duration of a sleet-ridden winter day but also to<br />

conserve the utterly singular trout that drive us to do it.<br />

-Sam Lungren, editor<br />

62 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL WINTER 2018